Abstract

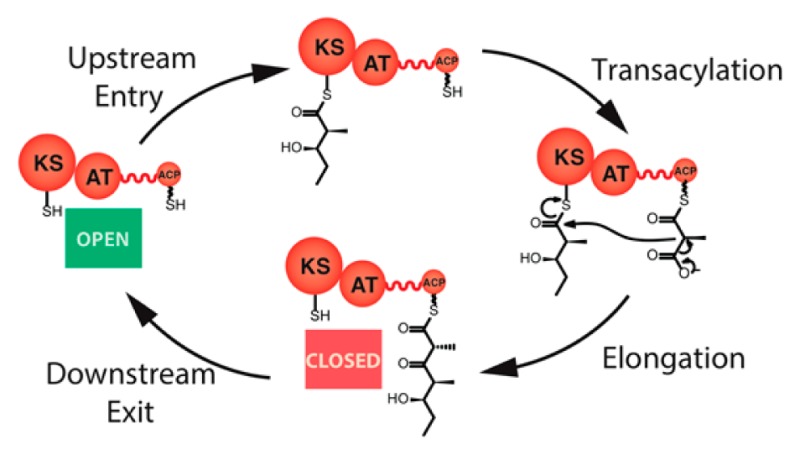

Vectorial polyketide biosynthesis on an assembly line polyketide synthase is the most distinctive property of this family of biological machines, while providing the key conceptual tool for the bioinformatic decoding of new antibiotic pathways. We now show that the action of the entire assembly line is synchronized by a previously unrecognized turnstile mechanism that prevents the ketosynthase domain of each module from being acylated by a new polyketide chain until the product of the prior catalytic cycle has been passed to the downstream module from the corresponding acyl carrier protein domain. The turnstile is closed by virtue of tight coupling to the signature decarboxylative condensation reaction catalyzed by the ketosynthase domain of each polyketide synthase module. Reopening of the turnstile is coupled to the eventual chain translocation step that vacates the module. At the maximal rate of substrate turnover, one would expect the chain release step to initiate a cascade of chain translocation events that sequentially migrate back upstream, thereby repriming each module and setting up the assembly line for the next round of polyketide chain elongation.

Short abstract

A turnstile mechanism for synchronized processing of intermediates on an assembly line polyketide synthase is identified. Chain elongation induces module closure, while chain translocation to the next module reopens the turnstile.

Introduction

Assembly line polyketide synthases (PKSs) are large multienzyme systems (MW ∼ 1–10 MDa) that produce hundreds of naturally occurring structurally complex metabolites.1,2 The prototypical example of an assembly line PKS is the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase (DEBS), which catalyzes the formation of the macrocyclic core of the antibiotic erythromycin.3,4 The DEBS assembly line is composed of three polypeptides (DEBS1, DEBS2, and DEBS3) that collectively harbor six homologous homodimeric modules. Each module catalyzes a sequence of reactions similar to those of fatty acid biosynthesis that extend the polyketide backbone by two carbon atoms followed by specific modifications of the oxidation level and stereochemistry before directed translocation of the resulting product to the correct downstream module (Figure S1). This multimodular architecture is the distinguishing feature of all naturally occurring assembly line PKSs and has inspired attempts to synthesize new natural products by genetic manipulation or rewiring of individual modules.5

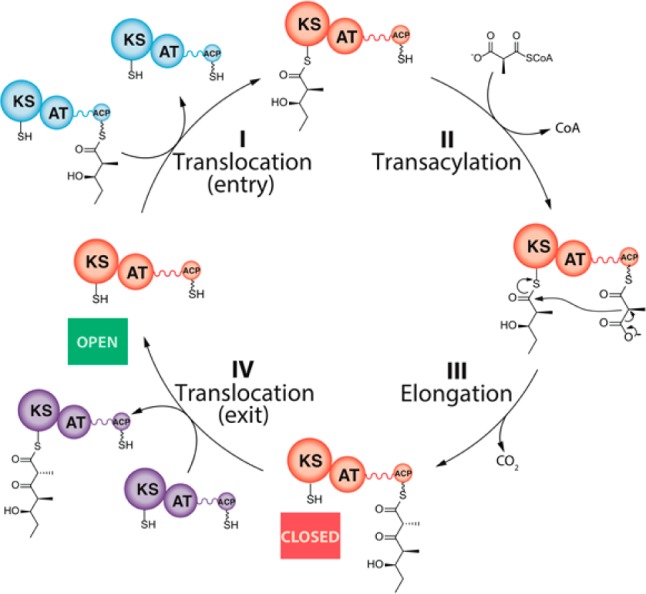

As shown in Figure 1, each PKS module has two sulfhydryl portals for covalently tethering the growing polyketide chain as a thioester: an entry site corresponding to the active site cysteine of the ketosynthase (KS) domain, and an exit site provided by the terminal thiol residue of the phosphopantetheinyl arm of the acyl carrier protein (ACP) domain. The entry site becomes occupied upon translocation of the growing polyketide chain from the ACP of the upstream module (step I). In the course of KS-catalyzed chain elongation (step III), the polyketide intermediate moves from the KS active site to the ACP-bound thiol within the same module. Although in principle this condensation reaction might be expected to free the KS domain to be able to catalyze immediately another translocation reaction involving a fresh biosynthetic intermediate acquired from the upstream module, we have now identified a previously unrecognized turnstile mechanism that prevents premature access to this KS domain. Importantly, only after the intramodular ACP domain has itself been vacated by a subsequent chain translocation to the KS of the corresponding downstream module (step IV) is the turnstile that controls access to the KS released so as to allow a fresh round of chain translocation and processing. In partnership with specific protein–protein recognition events, such a mechanism not only prohibits retrograde chain translocation (which would correspond to iterative chain elongation by a single KS) but also enforces the orderly vectorial progress of intermediates along the DEBS assembly line by allowing no more than a single polyketide chain to be tethered to each modular subunit at any time.

Figure 1.

Core catalytic cycle for a representative PKS module: A typical module (orange) catalyzes at least four transformations: (I) translocation of an incoming polyketide chain from the ACP of the upstream module (blue) to the active site cysteine residue of the KS domain; (II) AT-catalyzed transacylation of a substituted malonyl chain extender (depicted as a methylmalonyl unit) from the corresponding CoA thioester to the pantetheinyl side chain of an ACP; (III) chain elongation via a decarboxylative condensation between the acyl-KS and methylmalonyl-ACP; and (IV) translocation of the newly elongated chain to the KS domain of the downstream module (purple). In addition to these four reactions, most PKS modules harbor one or more auxiliary enzymatic domains that catalyze additional chain modification reactions (ketoreduction, dehydration, enoyl reduction) between steps III and IV. Although PKS modules are homodimeric, for convenience they are depicted as monomers in this and other schemes in this report. Their homodimeric architecture does not affect the conclusions drawn from this study.

The vectorial nature of assembly line polyketide biosynthesis is the most distinctive property of this family of biological machines, and is the principal conceptual and experimental tool for recognition and analysis of new polyketide pathways. While the directionality of biosynthesis on a given assembly line PKS can readily be inferred ipso facto if the structure of the resulting polyketide product is already known, the actual biochemical ordering of each module can rarely be assigned with any certainty if the resultant polyketide product is not known. This problem has represented a challenge of increasing significance as a result of the rapidly growing number of “orphan” assembly lines of unknown function that continue to be revealed by genomic sequencing programs. From an engineering standpoint, our limited understanding of the biochemical and protein structural basis for vectorial polyketide biosynthesis also precludes rational rewiring of heterologous PKS modules.

Unlike DNA or RNA polymerization or ribosomal protein biosynthesis, all of which are directed by an explicit DNA or ribonucleic template, polyketide biosynthesis is not controlled by a specific biochemical template or external instruction set. To explain the intrinsic programming of polyketide biosynthesis by a multimodular polyketide synthase, two distinct models have been suggested. One proposal posits that each module must have a strict structural and stereochemical preference for its natural substrate. While PKS modules do indeed exhibit an experimentally demonstrated level of intrinsic structural and stereochemical specificity for their incoming polyketide chains, both in vitro analysis of substrate specificity6 and in vivo studies of precursor-directed biosynthesis7,8 have revealed that individual modules nonetheless display a considerable range of substrate tolerance. Strict specificity for the incoming polyketide chain cannot therefore be the principal driver of the fidelity of vectorial biosynthesis on an assembly line PKS. An alternative model for programmatic control is based on the observed specificity of pairwise protein–protein interactions,9 most notably between the ∼200 kDa catalytic KS-AT core of each module10 and its two partnered acyl carrier protein (ACP) domains (Figure 1). Not only do the chain-donating and the chain-accepting ACP domains each specifically recognize the core KS-AT of each module during chain translocation11 and chain elongation,12 respectively, but these recognition events have been shown to involve distinct protein–protein interfaces13 that themselves may be subject to orthogonal evolutionary pressures.14

Results and Discussion

A vivid example of the importance of recognition between the ACP domain of donor module and the KS-AT core of the acceptor module is illustrated in Figure S2. Here, the turnover rate of a bimodular PKS, composed of DEBS modules 1 and 3, is enhanced by replacing a short region of the donor ACP domain of module 1 with its counterpart from the ACP domain of module 2. Such a modification was predicted to enhance intermodular chain translocation between modules 1 and 3 without impairing the chain elongation capacity of module 1 itself.

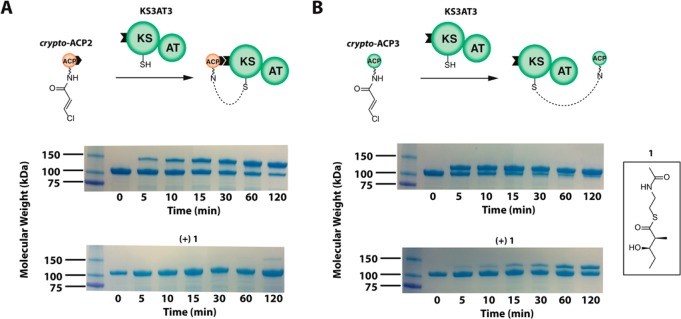

To probe more deeply into the role of protein–protein recognition between the catalytic core of a PKS module and each of its two distinct ACP partners, we have exploited a new chemical cross-linking strategy (Figure 2A). To this end, an electrophilic trans-3-chloroacrylamide is first tethered to an ACP, as previously described.15 Upon incubation of this crypto-ACP species with its partner KS domain, either within a full module or as a dissected KS-AT didomain, the two proteins rapidly become cross-linked. This cross-linking can be observed when a crypto-ACP is presented either to the KS core of its natural downstream module (chain translocation; Figure 2A, top) or to the paired KS core within the same module (chain elongation; Figure 2B, top). While prior occupation of the KS domain by a growing polyketide chain delivered as compound 1, a known substrate of KS3,16 completely blocks intermodular ACP-KS cross-linking (Figure 2A, bottom), it has a more modest inhibitory effect on the rate of intramodular ACP-KS cross-linking (Figure 2B, bottom). These observations are consistent with previous experiments that have established that an ACP engages the KS domain of its core module in a fundamentally different orientation during intermodular chain translocation than that used for intramodular chain elongation.13 Thus, the ACP-KS interactions during chain elongation mode (but not in chain translocation mode) must result in significant activation of the transiently formed acyl-KS thioester, as would be expected from the mechanism of the chain elongation reaction itself.

Figure 2.

Recognition of the catalytic KS-AT core of a PKS module by its two partner ACP domains. Transient protein–protein interactions were detected by cross-linking the catalytic core of DEBS module 3 (composed of functional KS and AT domains as well as flanking linkers, most notably the docking domains depicted as a black tab and explained in Figure S1) to modified forms of each of its two ACP partners, chain donor ACP2 and chain acceptor ACP3, both harboring an electrophilic probe at the end of their respective pantetheinyl arms. These modified proteins, designated crypto-ACPs, are excellent probes of protein–protein interactions between ACP domains and their partner enzymes in fatty acid and polyketide synthases.17,18 Synthesis of crypto-ACP2 and crypto-ACP3 is described in the Supporting Information. (A) crypto-ACP2 (250 μM; with its C-terminal flanking peptide, as explained in Figure S1) was incubated with KS3AT3 (50 μM) in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 5 mM diketide 1, which competitively acylates the KS active site. The lower band corresponds to the KS3AT3 protein (100 kDa), while the upper band corresponds to the cross-linked adduct between the crypto-ACP and KS3AT3 (121 kDa). (B) crypto-ACP3 (250 μM) was incubated with KS3AT3 (50 μM) in the absence (top) and presence (bottom) of 5 mM diketide 1. The smaller 12-kDa mass difference between monomeric KS3AT3 and the cross-linked adduct (112 kDa) reflects the absence of a C-terminal docking domain on crypto-ACP3.

The cross-linking results strongly augment our understanding of how non-covalent domain–domain interactions, both between KS-ACP pairs and between the attached intermodular docking domains, control the precise order of modular processing by a PKS assembly line. We have previously proposed that the free energy of reaction of the strongly exergonic KS-catalyzed decarboxylative condensation (step III; Figure 1) can in principle be harnessed to alter the accessibility of the module to incoming substrates at different states of the catalytic cycle. This fundamental principle was originally articulated more than three decades ago by Jencks to explain the empirically observed unidirectional nature of coupled vectorial processes such as protein motor functions or ion pumps.19 In the simplest formulation, a two-state vectorial model (Figure 1) could be applied to a canonical PKS module in which step III acts as the specificity switch. In one state, between steps II and III, characterized by covalent binding of the growing polyketide chain to the KS and the attachment of an α-carboxyacyl extender unit to the ACP, the KS domain of the core module would bind tightly to the ACP from its own module. At all other points along the catalytic cycle, the KS should in principle be free to interact with its upstream ACP partner, while the paired intramodular ACP and its tethered substrates can interact with auxiliary catalytic domains in the same module as well as the downstream KS-AT domain in the PKS assembly line.

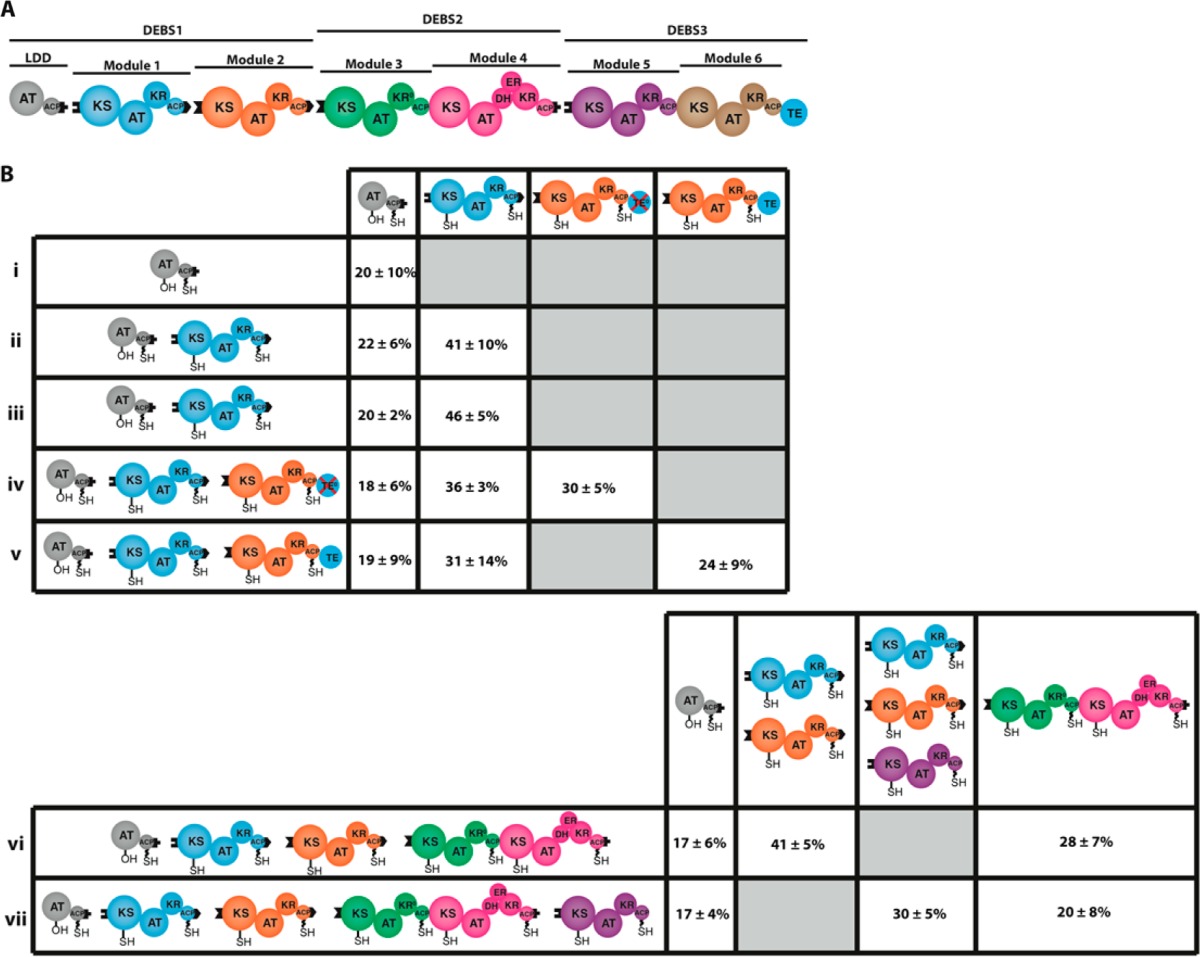

In this simple two-state model for vectorial biosynthesis, steps I and IV (Figure 1) need not occur in the specific order shown, since each chemical step involves a distinct pair of KS and ACP domains. Thus, a module in which one subunit is simultaneously occupied by two growing polyketide chains could in principle be just as likely as a fully vacant module. In order to determine the actual degree of occupancy of a functioning module, we used a [14C]-isotopic labeling assay to probe reconstituted fully active one-, two-, four-, and five-module derivatives of DEBS20 and then measured the actual covalent occupancy of individual modules within each modular protein ensemble. Significantly, under steady state conditions in no case could a PKS modular subunit anchor on average more than one growing polyketide chain, regardless of whether or not active polyketide chain release can take place, either by KS-catalyzed intermodular translocation or by thioesterase (TE)-catalyzed deacylation of the furthest downstream ACP (Table 1). Notably, steady state turnover was achieved in less than 5 min in each case and could be maintained for more than 15 min (Figures S6, S8, and S10).

Table 1. Fractional Occupancy by Growing Polyketide Chains of ACP + KS Active Sites within Individual Modules of Selected DEBS Variantsa.

(A) Schematic of the reconstituted DEBS. Each module, as well as the loading didomain (LDD), which primes the most upstream KS domain, and the TE, which catalyzes hydrolytic release of the mature polyketide chain, is shown in a distinct color. DEBS variants were reconstituted as previously described20 from five proteins: LDD, module 1, module 2, DEBS2, and DEBS3. (B) Percent of the combined ACP + KS occupancy within uni- and bimodular derivatives of DEBS (i–v) and percent of the combined ACP + KS occupancy in 4- and 5-module variants (vi, vii). All but one PKS assembly line (v) used in these experiments lacked an active thioesterase (TE) domain. For methodological details, see Supporting Information. In all experiments, DEBS proteins were incubated with 14C-propionyl-CoA and methylmalonyl-CoA, with the exception of i and ii, from which methylmalonyl-CoA was omitted. Occupancy was estimated by radio-SDS–PAGE analysis of each DEBS protein, with measurements in two systems (vi and vii, columns 2 and 3) being performed on multiple comigrating proteins. In these cases, the reported occupancy values were normalized to the corresponding number of thiol carriers. Occupancy values are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 3) of the ACP + KS occupancy after 15 min incubation. For details, see Figures S3–S6, S8, and S10.

In order to establish whether the observed partial occupancy of all modules was biased toward the KS or toward the ACP domain, incubations with module 1 were analyzed by mass spectrometry. As shown in Figure S7, at steady state it is primarily the ACP domain that becomes occupied. This finding indicates that step IV of the catalytic cycle illustrated in Figure 1 actually precedes step I for a PKS module operating under steady state conditions. The sequential nature of the outgoing and incoming chain translocation events thus ensures that only the KS or the ACP within each catalytic pair of a homodimeric module is occupied at any one time by a growing polyketide chain. Since access to the KS is transiently blocked in step III in the manner of a turnstile before subsequent release for further action in step IV, there must therefore also be a third, fully vacant, catalytic state of the PKS module (labeled “OPEN” in Figure 1) that is distinct from the both the pre-condensation state, in which both the electrophilic and nucleophilic substrates are bound within the module to their respective KS- and ACP-derived thiol residues (linking steps II and III), and the post-condensation state, which corresponds to a vacant KS and a newly elongated chain tethered to the ACP (labeled “CLOSED” in Figure 1).

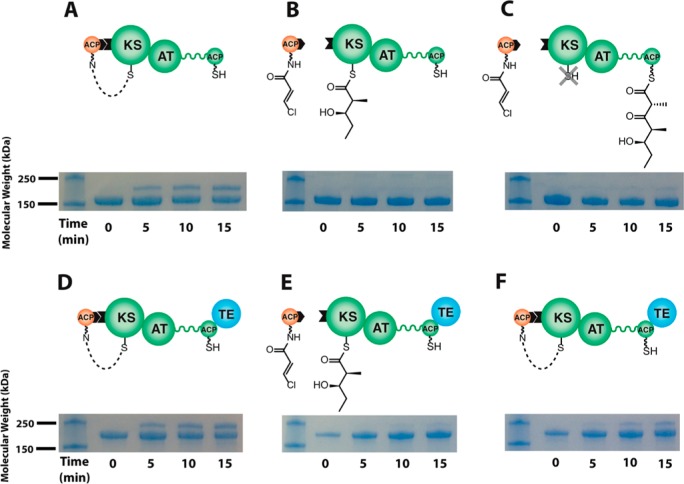

We further tested this expanded three-state model for vectorially controlled assembly line polyketide biosynthesis by applying the above-described protein cross-linking strategy (Figure 2) using a preparation consisting of an intact DEBS module 3 in combination with the ACP domain from DEBS module 2. Co-incubation of crypto-ACP2 with module 3 resulted in rapid cross-linking of the two proteins (Figure 3A). Not only could this cross-linking be inhibited, as expected, by pre-acylating module 3 with diketide analogue 1 (Figure 3B), but most importantly, this inhibition persisted even after the diketide had undergone chain elongation upon addition of methylmalonyl-CoA (Figure 3C), thus establishing that the turnstile controlling access to the KS active site is directly coupled to polyketide chain elongation itself. Further evidence for the turnstile mechanism was obtained from analogous experiments using DEBS module 3 + TE (Figure 3D–F). Within as little as 1 min after extender unit addition, the KS active site begins to revert to the open state (Figure 3F), presumably as a result of TE-catalyzed hydrolytic release of the newly elongated polyketide chain.

Figure 3.

Recognition of a PKS module by its upstream ACP partner. Protein interactions were detected by cross-linking either DEBS module 3 (A–C) or module 3 + TE (D–F) to a modified form of its upstream ACP partner from DEBS module 2. Synthesis of crypto-ACP2 is described in the Supporting Information. crypto-ACP2 (250 μM) was incubated with module 3 or module 3 + TE (50 μM) in the absence (A, D) or presence (B, E) of 10 mM diketide 1 (shown in Figure 2), which acylates the KS active site of module 3 or module 3 + TE. The lower protein band in each SDS–PAGE image corresponds to module 3 (160 kDa) or module 3 + TE (186 kDa), whereas the upper band corresponds to the cross-linked adduct between the crypto-ACP and module 3 (181 kDa) or module 3 + TE (207 kDa). In panels C and F, the crypto-ACP (250 μM) was incubated with module 3 or module 3 + TE (50 μM) that had been preincubated with diketide 1 plus methylmalonyl-CoA thus enabling elongation of the diketide chain. Chain elongation was initiated by addition of methylmalonyl-CoA, and allowed to proceed for 1 min with either module. Whereas the absence of cross-linking in panel C indicates generation of a closed turnstile in module 3 following chain elongation (as represented by the “X” over the KS active site thiol), the appearance of a cross-linked adduct in panel F indicates that TE-catalyzed hydrolysis of the elongation product allows the reopening of the turnstile.

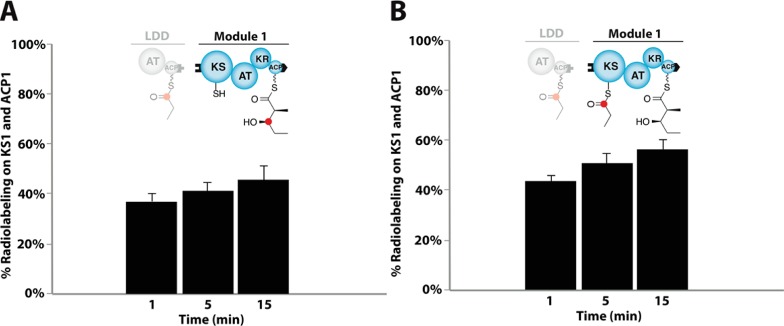

Two distinct models can explain the operation of the apparent mechanistic turnstile. In one scenario, the free energy associated with chain elongation itself is used to trap the module (by either a covalent or a non-covalent mechanism) in a state in which the KS active site is shielded from the upstream ACP with its attached polyketide chain. Alternatively, a closed turnstile might result solely from attachment of a nascent polyketide chain to the paired intramodular ACP domain without explicit energetic coupling to the decarboxylative condensation reaction that loads the chain elongation product onto the acceptor ACP. To distinguish between these two possibilities, the apo-ACP domain of DEBS module 1 was chemoenzymatically pre-acylated by incubation with a diketide-CoA substrate in the presence of the Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. The resultant module thus harbored the chemical equivalent of the product of its natural chain elongation reaction tethered to its ACP domain. Unlike its counterpart that participates in a canonical KS-catalyzed condensation (Figure 4A), the active site of the KS domain in the chemoenzymatically preloaded module could be shown to be fully accessible to the upstream ACP (Figure 4B). An analogous experiment involving DEBS module 2 (Figure S11) also led to the same conclusion. We therefore hypothesize that the closure of the turnstile in a PKS module is directly coupled energetically to the KS-catalyzed decarboxylative condensation itself. Similarly, reopening of the turnstile is a temporally, physically, and chemically discrete event (Figure 3) that relicenses the KS domain to accept a new polyketide primer from the upstream ACP and reinitiate the chain elongation cycle.

Figure 4.

Energetic coupling of the turnstile to polyketide chain elongation. In panel A, the ACP-bound diketide product of DEBS module 1 was generated by mixing holo-module 1 with DEBS loading didomain (LDD), 1-14C-propionyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, and NADPH. Consistent with data shown in Table 1B and Figure S6, radiolabel accumulated rapidly on module 1 and attained steady state corresponding to ∼50% occupancy of the ACP + KS sites. In contrast, in panel B the ACP domain of apo-module 1 was directly loaded with the formal diketide product of its chain elongation reaction. This was accomplished using the Coenzyme A thioester analogue of unlabeled diketide 1 in the presence of Sfp phosphopantetheinyl transferase. When the resulting module was mixed with LDD, 1-14C-propionyl-CoA, methylmalonyl-CoA, and NADPH, it was rapidly radiolabeled to a comparable steady state occupancy level, indicative of efficient translocation of 14C-propionyl units onto the KS domain of module 1. In both panels the occupancy values are reported as the mean ± SD (n = 3) of the ACP + KS occupancy for DEBS module 1. For experimental details, see the Supporting Information.

Conclusion

This report builds on and extends earlier findings by providing significant new data that reveal both how protein–protein recognition defines the proper ordering of modules on a PKS assembly line and how the core reactions catalyzed by each of the individual modules are energetically coupled to vectorial chain translocation. Under steady state turnover conditions no more than one polyketide chain is bound to the catalytic subunit of each homodimeric module. To synchronize the action of the entire assembly line, Nature has evolved an ingenious turnstile mechanism by which the KS domain of each module is prevented from acylation by a fresh polyketide chain until the product of the immediately prior chain elongation and modification reactions has departed from the paired ACP domain, either by further intermodular chain translocation to the KS domain of the downstream module or by final TE-catalyzed chain release. The turnstile is closed by virtue of the tight coupling to the KS-catalyzed decarboxylative condensation itself (step III), which significantly is the most exergonic reaction in the catalytic cycle mediated by the PKS module. Reopening of the turnstile is coupled to the eventual chain translocation step that vacates the module (step IV). Each module of an assembly line PKS therefore progresses through a minimally three-state catalytic cycle. At the maximum steady-state rate of turnover, one would expect the final TE-catalyzed chain release step to initiate a new cascade of chain translocation events that sequentially migrate upstream, thereby priming the assembly line for the next round of polyketide chain elongation. The precise chemical basis for the extraordinary turnstile mechanism demonstrated here remains to be elucidated. Previous research has established that the β-ketoacyl synthase domain of the rat fatty acid synthase releases bicarbonate upon decarboxylation, implicating a water molecule in the active site as a nucleophile.21 As a working hypothesis, we speculate that installation of the turnstile might involve covalent capture of the CO2 leaving group from the α-carboxyacyl extender unit as the carbamoyl derivative of the ε-amino group of the conserved lysine or a carbonate ester at a highly conserved threonine residue in the KS active site. (Alternatively, a relatively stable conformational change cannot be excluded.) The release of the turnstile would then correspond to displacement of the trapped carboxyl, perhaps via transient displacement as a thiocarbonate ester by the free thiol of the ACP. The use of high-resolution mass spectrometry is expected to further corroborate our findings of mono-occupancy of a PKS subunit.

The goal of understanding assembly line PKSs at a level of detail that enables rational engineering has been a longstanding yet elusive one. The turnstile mechanism for controlling chain growth further enhances our knowledge of how an assembly line performs vectorial biosynthesis. Further elucidation of this remarkable mechanistic feature will undoubtedly influence choices made by biosynthetic engineers. The evolution of the turnstile may well been the fundamental evolutionary event that enabled the emergence of assembly line polyketide synthases as the dominant subgroup of the PKS superfamily.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. T. Walsh for his critique of this manuscript. We also thank Dr. Josh Elias for advice and access to LC–-MS instrumentation. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (GM087934 to C.K. and GM022172 to D.E.C.).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00321.

Experimental methods, radio-SDS–PAGE data, plasmid construction, and mass spectra (PDF)

Author Present Address

‡ B.L.: AbbVie Inc., North Chicago, IL 60064, United States.

Author Contributions

§ The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript. B.L., X.L., and T.R. contributed equally.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Walsh C. T. Polyketide and nonribosomal peptide antibiotics: modularity and versatility. Science 2004, 303, 1805–1810. 10.1126/science.1094318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien R. V.; Davis R. W.; Khosla C.; Hillenmeyer M. E. Computational identification and analysis of orphan assembly-line polyketide synthases. J. Antibiot. 2014, 67, 89–97. 10.1038/ja.2013.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes J.; Haydock S.; Roberts G. An unusually large multifunctional polypeptide in the erythromycin-producing polyketide synthase of Saccharopolyspora erythraea. Nature 1990, 348, 176–178. 10.1038/348176a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donadio S.; Staver M.; McAlpine J. Modular organization of genes required for complex polyketide biosynthesis. Science 1991, 252, 675–679. 10.1126/science.2024119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertweck C. Decoding and reprogramming complex polyketide assembly lines: prospects for synthetic biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015, 40, 189–199. 10.1016/j.tibs.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J.; Kinoshita K.; Khosla C.; Cane D. E. Biochemical analysis of the substrate specificity of the beta-ketoacyl-acyl carrier protein synthase domain of module 2 of the erythromycin polyketide synthase. Biochemistry 2004, 43, 16301–16310. 10.1021/bi048147g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J.; Murli S.; Kealey J. T. 6-Deoxyerythronolide B Analogue Production in Escherichia coli through Metabolic Pathway Engineering. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 14342–14348. 10.1021/bi035157t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey C. J. B.; Puglisi J. D.; Pande V. S.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Precursor directed biosynthesis of an orthogonally functional erythromycin analogue: selectivity in the ribosome macrolide binding pocket. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 12259–12265. 10.1021/ja304682q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokhale R. S.; Tsuji S. Y.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Dissecting and Exploiting Intermodular Communication in Polyketide Synthases. Science 1999, 284, 482–485. 10.1126/science.284.5413.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Y.; Kim C.-Y.; Mathews I. I.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. The 2.7-Angstrom crystal structure of a 194-kDa homodimeric fragment of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11124–11129. 10.1073/pnas.0601924103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Quantitative analysis of the relative contributions of donor acyl carrier proteins, acceptor ketosynthases, and linker regions to intermodular transfer of intermediates in hybrid polyketide synthases. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 5056–5066. 10.1021/bi012086u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A. Y.; Schnarr N. A.; Kim C.-Y.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Extender unit and acyl carrier protein specificity of ketosynthase domains of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 3067–3074. 10.1021/ja058093d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S.; Chen A.; Cane D.; Khosla C. Molecular recognition between ketosynthase and acyl carrier protein domains of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 22066–22071. 10.1073/pnas.1014081107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S.; Lowry B.; Yuzawa S.; Kenthirapalan S.; Chen A. Y.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Reprogramming a module of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase for iterative chain elongation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 4110–4115. 10.1073/pnas.1118734109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur S.; Worthington A.; Tang Y.; Cane D. E.; Burkart M. D.; Khosla C. Mechanism based protein crosslinking of domains from the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2008, 18, 3034–3038. 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu N.; Kudo F.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. Analysis of the Molecular Recognition Features of Individual Modules Derived from the Erythromycin Polyketide Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 4847–4852. 10.1021/ja000023d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Worthington A. S.; Rivera H.; Torpey J. W.; Alexander M. D.; Burkart M. D. Mechanism-based protein cross-linking probes to investigate carrier protein-mediated biosynthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 2006, 1, 687–691. 10.1021/cb6003965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beld J.; Cang H.; Burkart M. D. Visualizing the Chain-Flipping Mechanism in Fatty-Acid Biosynthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 14456–14461. 10.1002/anie.201408576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks W. P. The utilization of binding energy in coupled vectorial processes. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 2006, 51, 75–106. 10.1002/9780470122969.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry B.; Robbins T.; Weng C.-H.; O’Brien R. V.; Cane D. E.; Khosla C. In vitro reconstitution and analysis of the 6-deoxyerythronolide B synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 16809–16812. 10.1021/ja409048k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkowski A.; Joshi A. K.; Smith S. Mechanism of the β-Ketoacyl Synthase Reaction Catalyzed by the Animal Fatty Acid Synthase. Biochemistry 2002, 41, 10877–10887. 10.1021/bi0259047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.