Abstract

Objective

The majority of acute coronary syndromes are caused by plaque ruptures. Proteases secreted by macrophages play an important role in plaque ruptures by degrading extracellular matrix proteins in the fibrous cap. Matrix metalloproteinases have been shown to be markers for cardiovascular disease whereas the members of the cathepsin protease family are less studied.

Methods

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B were measured in plasma at baseline from 384 individuals who developed coronary events (CEs), and from 409 age-matched and sex-matched controls from the Malmö Diet and Cancer cardiovascular cohort.

Results

Cathepsin D (180 (142–238) vs 163 (128–210), p<0.001), cathepsin L (55 (44–73) vs 52 (43–67), p<0.05) and cystatin B levels (45 (36–57) vs 42 (33–52), p<0.001) were significantly increased in CE cases compared to controls. In addition, increased cathepsin D (220 (165–313) vs 167 (133–211), p<0.001), cathepsin L (61 (46–80) vs 53 (43–68), p<0.05) and cystatin B (46 (38–58) vs 43 (34–54), p<0.05) were associated with prevalent diabetes. Furthermore, cathepsin D and cystatin B were increased in smokers. The HRs for incident CE comparing the highest to the lowest tertile(s) of cathepsin D and cystatin B were 1.34 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.75) and 1.26 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.57), respectively, after adjusting for age, sex, low-density lipoprotein/high-density lipoprotein ratio, triglycerides, body mass index, hypertension and glucose, but these associations did not remain significant after further addition of smoking to the model. In addition, cathepsin D was increased in incident CE cases among smokers after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors.

Conclusions

The associations of cathepsin D and cystatin B with future CE provide clinical support for a role of these factors in cardiovascular disease, which for cathepsin D may be of particular importance for smokers.

Keywords: cathepsin D, cystatin B, diabetes, coronary events

Key questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Matrix metalloproteinases have been shown to be markers for cardiovascular disease whereas the members of the cathepsin protease family are less studied.

What does this study add?

In this study, we show that high plasma levels of the protease cathepsin D are associated with increased risk for future coronary syndromes. Futhermore, in smokers, cathepsin D is increased and independently associated with coronary syndromes.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The results provide clinical support for a role of cathepsin D and cystastin B in cardiovascular disease, which for cathepsin D may be of particular importance for smokers.

Introduction

The majority of acute coronary syndromes are caused by plaque ruptures resulting in embolisation or thrombotic occlusion of vessels. Vulnerable plaques, which are more prone to rupture, are characterised by a large lipid-rich necrotic core in combination with a thin fibrous cap infiltrated by macrophages and T lymphocytes, but with fewer smooth muscle cells. The underlying processes causing plaque rupture involve accumulation of pro-inflammatory and toxic lipids, changes in shear stress, degradation of extracellular matrix proteins by macrophage proteases and impaired tissue repair due to smooth muscle cell death.1 One major class of proteases in the vessel wall are the matrix metalloproteinases, which are inhibited by the naturally occurring tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases.2 While a number of studies have identified different matrix metalloproteinases as possible plasma markers of cardiovascular events, less is known about the members of the cathepsin protease family.

Cathepsins are normally present intracellularly in lysosomes but can in some cases be secreted and found in human serum. While normal arteries contain no or small amounts of cathepsins, increased expression is seen in abdominal aneurysms, as well as in macrophages and smooth muscle cells present within atherosclerotic lesions.3–6 Pro-inflammatory mediators induce cathepsin expression in aortic macrophages and smooth muscle cells, and increase the matrix degrading activity, thus implicating a role for cathepsins in plaque destabilisation.7 Furthermore, cathepsins influence macrophage apoptosis, which may further increase plaque vulnerability.6

Studies on human atherosclerotic lesions have shown that cathepsin L is associated with plaque destabilisation and apoptosis.6 8 9 Cathepsin L is also expressed in endothelial cells and is suggested to play a role in flow-induced vascular remodelling and atherogenesis.10 Clinical studies have shown that plasma/serum levels of cathepsin L are increased in patients with coronary artery stenosis, as well as in patients with abdominal aortic aneurysms.11 12 However, the association between plasma levels of cathepsin L and risk for future coronary events (CEs) has not been studied previously.

Less is known about cystatin B, an inhibitor of cathepsin L, and cardiovascular disease (CVD). Cystatin B levels in tissue and body fluids have been suggested as biomarkers in some cancers.13–15 Mutations in the cystatin B gene are linked to progressive myoclonus epilepsy 1, a neurodegenerative disorder.16 Recently, cystatin B in plasma has been proposed as a biomarker for cardiovascular disease based on data obtained from a small patient cohort.17

Cathepsin D has been suggested as an independent prognostic factor in a variety of cancers.18 Under pathological conditions, cathepsin D is present extracellularly in tissues, such as in the synovia of patients with rheumatoid arthritis,19 in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease,20 in invasive carcinomas and in macrophage-rich regions of human atherosclerotic lesions.3 In addition, cathepsin D has been implicated in apoptosis of macrophages.6 Interestingly, proteomic studies have identified cathepsin D as a potential novel biomarker of CVD. In these studies, cathepsin D was shown to be increased in cell supernatants of oxidised low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-stimulated macrophages, as well as in supernatants of ex vivo plaques compared to control samples.21–23

Although cathepsin D and cystatin B have both been proposed as biomarkers for cardiovascular disease in proteomic studies or small patient cohorts, so far, they have not been investigated in a prospective cardiovascular cohort. In the present study, we investigated if plasma levels of cathepsin D, as well as cathepsin L, and its inhibitor cystatin B, are associated with future CEs.

Materials and methods

Malmö Diet and Cancer cohort

The Malmö Diet and Cancer (MDC) study is a population-based, prospective cohort of 28 449 individuals enrolled between 1991 and 1996.24 From this cohort, 6103 persons were randomly selected to participate in the MDC Cardiovascular Cohort (MDC-CC), which was designed to investigate the epidemiology of carotid artery disease. Of MDC-CC participants, fasting plasma samples were available in 5540 participants, of whom we excluded 143 participants who had CVD prior to the baseline examination. During a mean follow-up time of 14.0±4.3 years, 402 first-incident CEs occurred. A CE was defined as a fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction (ie, International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) code 410)) or death attributable to underlying coronary heart disease (ICD-9 codes 410–414). We matched 402 incident CE cases with 402 CVD-free control subjects based on gender and age, also requiring that the follow-up time of the control was at least as long as that of the corresponding incident CE case. Plasma samples were available and analysed from 384 cases and 401 controls. In addition eight plasma samples from extra controls, matched as above, were analysed. Blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), smoking status, white blood cell count, glycated haemoglobin, fasting glucose and lipoprotein lipid levels were determined as previously described.25–27 The study was approved by the local Regional Ethical Review Board. All participants gave written consent.

Analysis of cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B in plasma

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L1 and cystatin B were analysed in plasma from 793 individuals included in the MDC-CC. Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B were analysed by the Proximity Extension Assay technique using the Proseek Multiplex CVD96×96 reagents kit (Olink Bioscience, Uppsala, Sweden) at the Clinical Biomarkers Facility, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala, Sweden. Polyclonal antibodies, raised using recombinant human cathepsin D (amino acids Leu21-Leu412), cathepsin L (amino acids Glu113-Val333) and cystatin B (amino acids Met2-Phe98), were used. Oligonucleotide labelled antibody probe pairs were allowed to bind to their respective targets present in the plasma sample. Addition of a DNA polymerase led to an extension and joining of the two oligonucleotides, and formation of a PCR template. Universal primers were used to pre-amplify the DNA templates in parallel. Finally, the individual DNA sequences were detected and quantified using specific primers by microfluidic real-time quantitative PCR chip (96.96, Dynamic Array IFC, Fluidigm Biomark). Further technical details of the assay, by Assarsson et al, have been published.28 The chip was run with a Biomark HD instrument. The mean coefficients for intra-assay variation were 8% (cathepsin D and cystatin B) or 7% (cathepsin L) and interassay variation was 16% (cathepsin D), 14% (cathepsin L) or 13% (cystatin B). Further details about limit of detection (LOD), reproducibility and validations are given at Olink webpage (http://www.olink.com/products/proseek-multiplex/downloads/data-packages). Data analysis was performed by a preprocessing normalisation procedure using Olink Wizard for GenEx (Multid Analyses, Sweden).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean±SD for normally distributed data and as median (IQR) for non-normally distributed data. Two-group comparisons of normally distributed data were analysed using t test and non-normally distributed variables were analysed using Mann-Whitney test. Differences in categorical variables were analysed using χ2 test. Correlations were performed using Spearman's correlation coefficient. Bonferroni was used to correct for multiple testing. Kaplan-Meier curves were used to illustrate incidence of CE over time in relation to tertiles of plasma levels of cystatin B, cathepsin D or cathepsin L, respectively. Differences were analysed using log-rank test (Mantel-Cox). A Cox proportional hazard regression model was used to correct for interferences between cardiovascular risk factors and associations between levels of cystatin B, cathepsin D or cathepsin L in tertiles and incident CE. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to correct for interferences between cardiovascular risk factors and associations between levels of cystatin B, cathepsin D or cathepsin L as standardised variables and incident CE among smokers. Non-normally distributed variables were ln-transformed in the Cox proportional hazard and binary logistic regression analyses.

Results

Association of cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B to incident CE

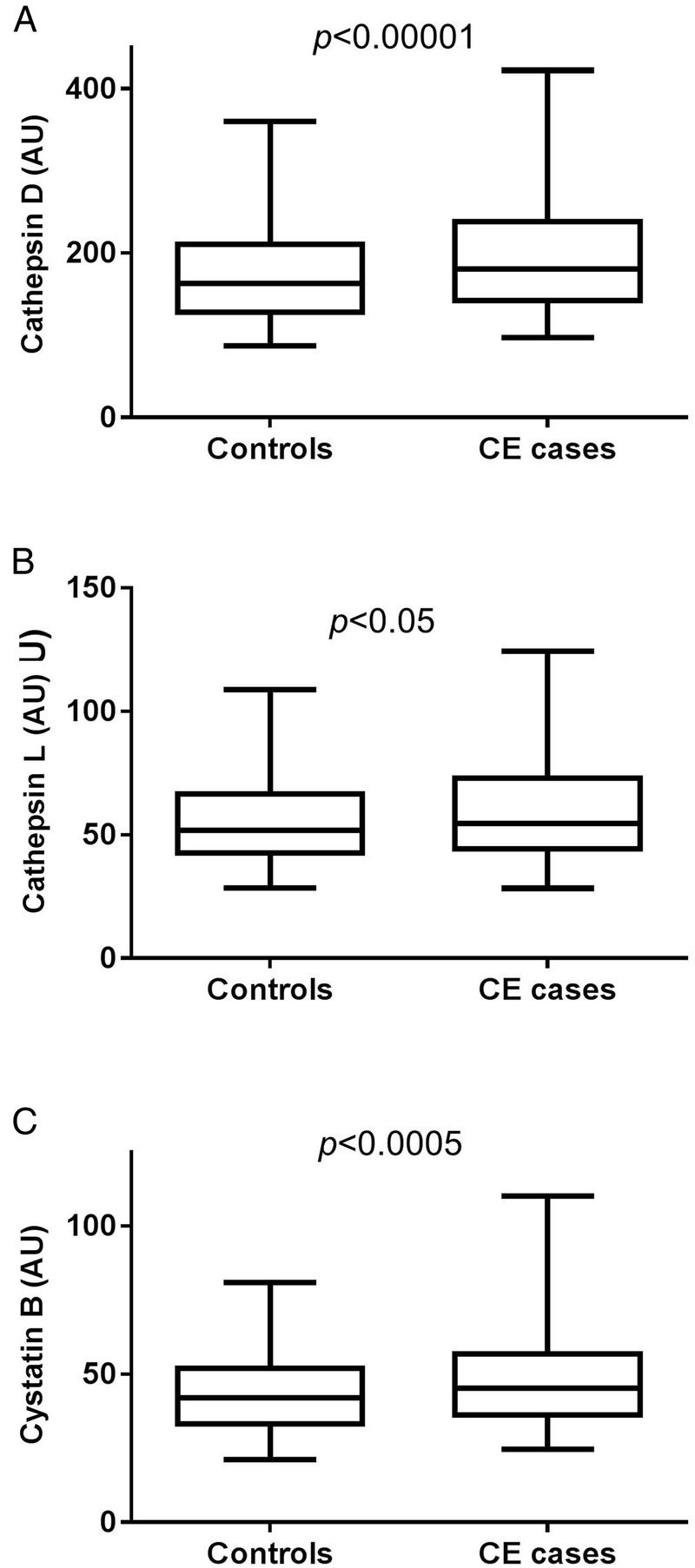

To test if plasma levels of cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B are associated with future cardiovascular events, we analysed baseline samples from 384 individuals who later developed CE, and from 409 age-matched and sex-matched controls participating in the MDC-CC. Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. Levels of cathepsin D (180 (142–238) vs 163 (128–210), p<0.0001) and cathepsin L (55 (44–73) vs 52 (43–67), p<0.05), as well as cystatin B (45 (36–57) vs 42 (33–52), p<0.0005), were increased in participants with incident CE, although the difference was more pronounced for cathepsin D and cystatin B than for cathepsin L (figure 1).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of incident CE cases and controls from the MDC-CC

| Controls (n=409) | Cases (n=384)† | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at screening, years | 60.2±5.3 | 60.1±5.4 |

| Sex (% men) | 245/409 (59.9) | 230/384 (59.9) |

| Current smoker, % | 103/399 (25.8) | 132/363 (36.4)** |

| Hypertension, %‡ | 283/409 (69.2) | 302/384 (78.6)** |

| Diabetes mellitus, %§ | 34/409 (8.3) | 77/382 (20.2)*** |

| Medication | ||

| Blood pressure lowering, % | 67/409 (16.4) | 83/384 (21.6) |

| Antidiabetic, % | 5/409 (1.2) | 28/384 (7.3)*** |

| Lipid lowering,% | 7/409 (1.7) | 14/384 (3.6) |

| Laboratory parameters | ||

| Fasting blood glucose, mmol/L | 4.9 (4.6–5.3) | 5.1 (4.7–5.6)*** |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.2 (0.9–1.7) | 1.4 (1.0–1.9)** |

| HDL, mmol/L | 1.3±0.4 | 1.2±0.4*** |

| LDL, mmol/L | 4.2±1.0 | 4.3±1.0* |

| LDL/HDL ratio | 3.3±1.2 | 3.8±1.3*** |

| HbA1c, % | 4.8 (4.5–5.1) | 4.9 (4.6–5.4)*** |

| White blood cell counts (106 cells/mL) | 5.7 (5.0–6.8) | 6.4 (5.3–7.4)*** |

Normally distributed variables are presented as mean±SD; non-normally distributed variables are presented as median (IQR).

*p<0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001 for cases versus all non-cases.

†t Test for normally distributed data, Mann-Whitney test for non-normally distributed data and χ2 test for categorical data.

‡Blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg or antihypertensive treatment.

§History of diabetes mellitus, medication or fasting glucose ≥6.1 mmol/L.

CE, coronary event; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MDC-CC, Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort.

Figure 1.

Baseline plasma levels of cathepsin D (A), cathepsin L (B) and cystatin B (C) are increased in individuals who developed coronary events (CEs) during follow-up. Values are given as arbitrary units (AU) and demonstrating as boxplots, with whiskers indicating 2.5 and 97.5 centiles.

Association of cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B to cardiovascular risk factors

Baseline plasma cathepsin D levels correlated with factors associated with metabolic syndrome (high-density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, BMI, blood pressure and blood glucose) and type 2 diabetes, whereas no association was seen with LDL-cholesterol or total cholesterol (see online supplementary table S1). Cathepsin L demonstrated similar but less pronounced associations (see online supplementary table S1). Also, cystatin B was associated with factors involved in metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes, but in addition showed associations to LDL-cholesterol and total cholesterol. Both cathepsins and cystatin B were increased in participants with prevalent diabetes (table 2). The difference was more pronounced for cathepsin D than for cathepsin L and cystatin B. Higher levels of cathepsin D and cystatin B were also observed among current smokers (table 3), and cathepsin D levels correlated with amount of smoking in terms of number of cigarette packages per year (see online supplementary table S1). In addition, cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B were associated with white blood cell counts. After Bonferroni correction, cathepsin D was still associated with BMI, white blood cell counts, HDL, triglycerides, glucose, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), insulin, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure. Similarly, cystatin B was associated with BMI, white blood cell counts, HDL, triglycerides, HbA1c, insulin, systolic blood pressure and age, after Bonferroni correction. For cathepsin L only the associations to BMI, HDL, insulin and diastolic blood pressure remained after Bonferroni correction.

Table 2.

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B levels in individuals with and without diabetes

| Individuals without diabetes (n=680) | Individuals with diabetes (n=111) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin D | 167 (133–211) | 220 (165–313) | 10−11 |

| Cathepsin L | 53 (43–68) | 61 (46–80) | 0.001 |

| Cystatin B | 43 (34–54) | 46 (38–58) | 0.02 |

Values are expressed as median (IQR) in arbitrary units.

*Mann–Whitney test.

Table 3.

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B levels in non-smokers and smokers

| Non-smokers (n=527) | Smokers (n=235) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin D | 167 (133–212) | 182 (143–239) | 0.002 |

| Cathepsin L | 53 (43–69) | 54 (43–69) | 0.60 |

| Cystatin B | 42 (34–53) | 46 (37–56) | 0.005 |

Values are expressed as median (IQR) in arbitrary units.

*Mann–Whitney test.

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B, and incident CE, taking cardiovascular risk factors into account

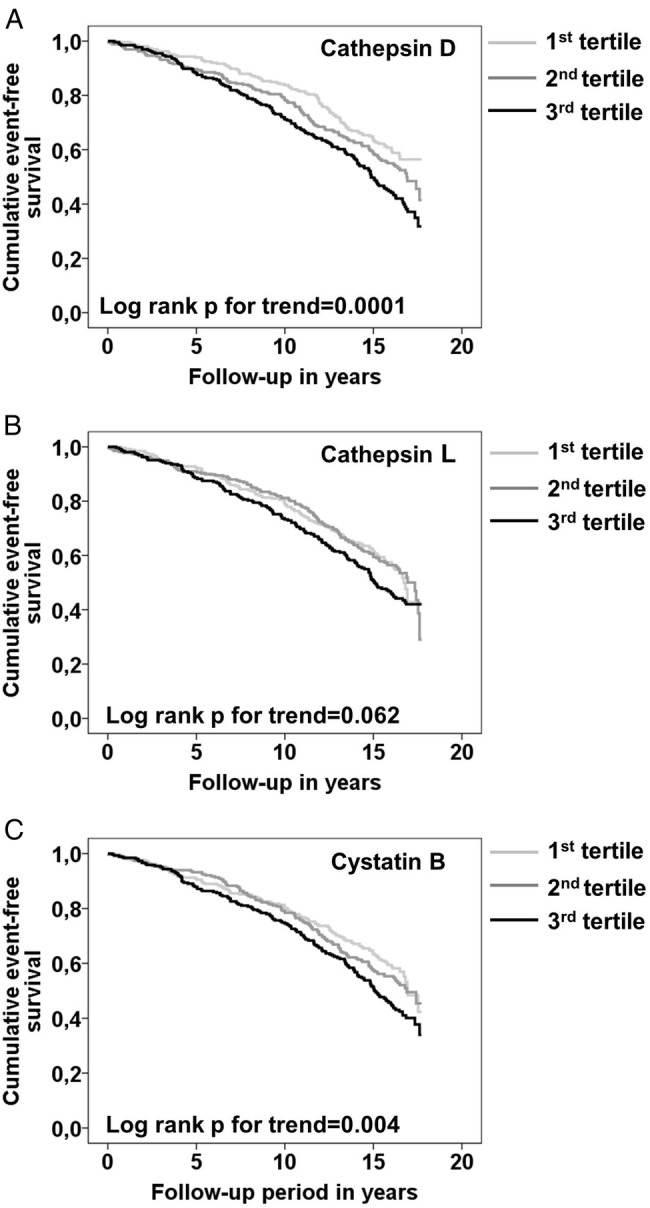

Next we tested if associations of cathepsins and cystatin B levels to future CE were independent of traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Analysing tertiles of cathepsin D by log-rank test suggested an association between cathepsin D levels and incident CE (figure 2A). The HR for an incident CE comparing the highest to the lowest tertile of cathepsin D was 1.62 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.08; p=0.0001) in a Cox proportional hazard model (table 4). Since cathepsin D was significantly increased in patients with prevalent diabetes as well as in smokers, four different models were used to analyse HR, taking potential confounders into account. The first model included age, sex, lipids (LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides), BMI and hypertension. In the second and third models, either glucose or smoking was added, and in the last model both glucose and smoking were included. Cathepsin D in tertiles was significantly (p for trend 0.033) associated with increased risk for incident CE after including age, sex, lipids, BMI, hypertension and glucose as potential confounders to the model (table 4). However, after further addition of smoking, tertiles of cathepsin D were no longer statistically significantly associated with increased risk for CE (p for trend 0.17). Tertiles of cathepsin L did not show a significant association to CE (p for trend 0.06; log-rank test) (figure 2B). However, we observed an increased risk for incident CE in the top tertile compared to the combined first and second tertile of cathepsin L (HR 1.26; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.55; p=0.03). This risk increase did not remain after adjusting for CV risk factors (data not shown). There was also a significant association between cystatin B and incident CE (figure 2C). The HR for incident CE in the highest compared to the bottom tertiles of cystatin B was 1.36 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.67; p=0.004) (table 5). The association remained significant after adjusting for age, sex, lipids, BMI, hypertension and glucose. However, when smoking was added to the model, this association did not remain statistically significant.

Figure 2.

Association between baseline plasma cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B levels, and incident coronary events (CEs) in the Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort (MDC-CC). Kaplan–Meier CE event-free survival curves in the study population by tertiles (1st tertile light grey, 2nd tertile dark grey, 3rd tertile black) of plasma cathepsin D (A), cathepsin L (B) and cystatin B (C). Significant positive trends over tertiles were tested using a log-rank test for trend.

Table 4.

HRs (95% CI) for incident coronary events by tertiles of cathepsin D in the MDC-CC

| First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathepsin D (AU) | <147 | 147–200 | >200 | |

| Coronary events (n) | 107 | 124 | 153 | |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)* | 1 | 1.22 (0.94 to 1.58) | 1.62 (1.27 to 2.08) | 0.0001 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)† | 1 | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.45) | 1.42 (1.09 to 1.85) | 0.009 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)‡ | 1 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.43) | 1.34 (1.02 to 1.75) | 0.033 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)§ | 1 | 1.11 (0.84 to 1.46) | 1.28 (0.97 to 1.69) | 0.074 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)¶ | 1 | 1.09 (0.83 to 1.44) | 1.22 (0.92 to 1.61) | 0.17 |

*Non-adjusted.

†Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI and hypertension.

‡Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension and glucose.

§Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension and current smoking.

¶Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension, glucose and current smoking.

AU, arbitrary units; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MDC-CC, Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort.

Table 5.

HRs (95% CI) for incident coronary events for tertile 1 and 2 versus tertile 3 of cystatin B in the MDC-CC

| First and second tertiles | Third tertile | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cystatin B (AU) | ≤50.2 | >50.2 | |

| Coronary events (n) | 236 | 148 | |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)* | 1 | 1.36 (1.10 to 1.67) | 0.004 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)† | 1 | 1.25 (1.00 to 1.55) | 0.051 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)‡ | 1 | 1.26 (1.01 to 1.57) | 0.044 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)§ | 1 | 1.15 (0.91 to 1.44) | 0.25 |

| Coronary events, HR (95% CI)¶ | 1 | 1.15 (0.91 to 1.45) | 0.23 |

*Non-adjusted.

†Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI and hypertension.

‡Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension and glucose.

§Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension and current smoking.

¶Adjusted for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI, hypertension, glucose and current smoking.

AU, arbitrary units; BMI, body mass index; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; MDC-CC, Malmö Diet and Cancer Cardiovascular Cohort.

Since cathepsin D and cystatin B were associated with both diabetes and current smoking, and significant associations with incident CE disappeared after further addition of smoking to the model, we explored this further in sensitivity analysis. First we analysed individuals without diabetes. Also, in individuals without diabetes, levels of cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B were increased in CE cases compared to controls (table 6). Cathepsin D and cystatin B levels in tertiles both remained significantly associated with incident CE after adjusting for age, sex, LDL/HDL ratio, triglycerides, BMI and hypertension in individuals without diabetes (see online supplementary tables S2 and S3). HR in the highest compared to lowest tertile of cathepsin D was 1.47 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.97; p=0.010). The corresponding HR for cystatin B was 1.39 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.77; p=0.008). As a next step, we analysed non-smoking individuals (n=527). Cathepsin D and cystatin B, but not cathepsin L, were significantly increased in incident CE cases compared to controls (table 6), however, these associations did not remain statistically significant taking cardiovascular risk factors into account (see online supplementary table S4). We then analysed current smokers (n=235). Both cathepsins and cystatin B levels were increased in incident CE compared to controls in current smokers (table 6). Cathepsin D, but not cathepsin L or cystatin B, was increased in incident CE cases among smokers, taking cardiovascular risk factors into account (see online supplementary table S5). The ORs for incident CE per SD for cathepsin D was 1.42 ((95% CI 1.02 to 1.97) p=0.038) after adjusting for age, sex, lipids, BMI, hypertension and glucose.

Table 6.

Cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B levels in incident coronary event (CE) cases compared to controls in individuals without diabetes, non-smokers or smokers

| Controls | Incident CE† | |

|---|---|---|

| Individuals without diabetes (n=680) | ||

| Number of individuals | 375 | 305 |

| Cathepsin D | 160 (126–197) | 174 (139–224)*** |

| Cathepsin L | 52 (42–66) | 54 (43–72)* |

| Cystatin B | 42 (33–51) | 46 (36–57)*** |

| Non-smokers or ex-smokers (n=527) | ||

| Number of individuals | 296 | 231 |

| Cathepsin D | 161 (128–209) | 172 (136–223)* |

| Cathepsin L | 52 (43–67) | 55 (44–72) |

| Cystatin B | 41 (33–51) | 43 (36–56)* |

| Smokers (n=235) | ||

| Number of individuals | 103 | 132 |

| Cathepsin D | 170 (130–218) | 199 (149–251)** |

| Cathepsin L | 51 (41–67) | 59 (45–76)* |

| Cystatin B | 43 (36–54) | 48 (37–58)* |

Values are expressed as median (IQR) in arbitrary units.

*p≤0.05.

**p<0.01.

***p<0.001.

†Mann–Whitney test.

Discussion

In the present study, we found that high plasma levels of cathepsin D, cystatin B and, to a lesser extent, cathepsin L, were associated with increased risk of future CE. In the MDC-CC, cathepsin D levels were significantly increased in individuals with prevalent diabetes, confirming previous studies of smaller patient cohorts.29 30 Moreover, cathepsin D levels were associated with factors included in the metabolic syndrome and diabetes, but not with LDL-cholesterol, one of the major risk factors for CVD in the general population. These correlations ranged from 0.19 to 0.31, thus explaining between 3.6% and 9.6% (r2=0.036–0.096) of the cathepsin D levels. Similar to cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B were increased in individuals with diabetes, and correlated with parameters associated with diabetes and metabolic syndrome, although these associations were less pronounced than for cathepsin D. However, the increase in cathepsin L (15%) and cystatin B (7%) levels in individuals with diabetes is rather small, and may therefore not be clinically relevant. Previous findings show that cathepsin D secretion is increased in macrophages stimulated with advanced glycated end-products as well as in adipocytes stimulated with insulin.31 32 In a recent study, cathepsin D was shown to be a marker for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.33 Despite the associations of cathepsin D and cystatin B to diabetes, both markers were still significantly increased in incident CE cases excluding prevalent diabetic individuals and after adjusting for lipids, BMI and hypertension. However, since the characteristics of the individuals are reported from the baseline examination, we cannot exclude that some of the individuals later became diabetic, which could affect the result.

Although the literature on cystatin B and CVD is sparse, a small scale study recently identified cystatin B as a possible biomarker for CVD.17 In the present study, we found that both proteolytic cathepsin L and its inhibitor cystatin B were increased in plasma from individuals who later developed CE. Although this may sound contradictory, it is possible that a high cathepsin L expression is regulated by increased cystatin B levels to limit the proteolytic activity. Knowledge from other diseases suggests that cystatin B and cathepsin expression may coincide. For example, during HIV-1 infection, both cystatin B and cathepsin B are upregulated in macrophages.34

Baseline plasma levels of cathepsin D and cystatin B were significantly increased in current smokers, and cathepsin D levels correlated with the amount of smoking. Furthermore, the association of cathepsin D and cystatin B to incident CE was lost after addition of smoking to the model. Even though cathepsin D and cystatin B were increased in participants with incident CE in non-smokers, these associations did not remain after taking cardiovascular risk factors into account. Furthermore, both cathepsin D and cystatin B were significantly increased in individuals with incident CE analysing smokers alone. This association remained significant for cathepsin D after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors. This implies that cathepsin D may be of particular importance for the development of future CE among smokers. In line with this, several studies have shown increased cathepsin levels/activity in plasma or alveolar macrophages in smokers.12 35 Previous studies on chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary emphysema have shown that cathepsin D expression or activity is increased in alveolar macrophages from smoke-exposed mice and from current smokers.36 37 It is possible that macrophages in atherosclerotic lesions from smokers express more cathepsin D, which could influence plaque stability.

Whether the high cathepsin D and cystatin B levels in plasma of individuals with incident CE reflect increased secretion from blood cells, endothelial cells, adipose tissue, or leakage from the vessel wall, or a combination of several of these, is unclear. In favour of the first possibility, a comparison of 27 acute coronary syndrome patients with 21 stable coronary disease patients or healthy controls displayed increased expression of mature cathepsin D in circulating monocytes as well as increased levels of cathepsin D in plasma from the patients with acute coronary syndrome.38 On the other hand, the correlations of cathepsin D and cystatin B to BMI may reflect an increased secretion from adipocytes. Recently, cathepsin S was shown to be one of the most upregulated genes in the adipose tissue of obese patients.39 Cystatin C, another cysteine cathepsin inhibitor, was previously shown to correlate with waist progression.40 In addition, insulin stimulation of adipocytes resulted in increased cathepsin D expression.31 In line with this, cathepsin D and cystatin B were associated with fasting insulin in our study. A third possibility is that the increased plasma levels of cathepsins and cystatin B are due to an increased secretion by vascular endothelial cells or leakage from the plaque. This is supported by several previous studies showing that cathepsin D is present in atherosclerotic lesions.3 5 6

Conclusion

In summary, we show that cathepsin D, cathepsin L and cystatin B are associated with increased incidence of CE. The findings provide clinical support for these factors in cardiovascular disease, which for cathepsin D may be of particular importance among smokers.

Footnotes

Contributors: IG, GNF, HB, JN and EB designed the study. IG, KH, PD, AE, BH, GNF, HB and EB analysed and interpreted the data. IG, KH and EB drafted the manuscript. PD, AE, BH, GNF, HB and JN critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All the authors gave final approval of the submitted version.

Funding: This work was supported by the Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (20140327, 20140078, 20140532, 20120407, 20130572, 20140427, 20140357, 20130554, 20130363), Swedish Research Council (2015-0052, K2013-65X-22345-01-3, K2011-65x-08311-24-6), Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg, SUS Foundations, Ernhold Lundström Foundation, The Swedish Society of Medicine, Diabetesfonden, Albert Påhlsson Foundation and Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund/Malmö.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Sakakura K, Nakano M, Otsuka F et al. Pathophysiology of atherosclerosis plaque progression. Heart Lung Circ 2013;22:399–411. 10.1016/j.hlc.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newby AC. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibition therapy for vascular diseases. Vascul Pharmacol 2012;56:232–44. 10.1016/j.vph.2012.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hakala JK, Oksjoki R, Laine P et al. Lysosomal enzymes are released from cultured human macrophages, hydrolyze LDL in vitro, and are present extracellularly in human atherosclerotic lesions. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:1430–6. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000077207.49221.06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jormsjo S, Wuttge DM, Sirsjo A et al. Differential expression of cysteine and aspartic proteases during progression of atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Am J Pathol 2002;161:939–45. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64254-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaesberg B, Harrach B, Dieplinger H et al. In situ immunolocalization of lipoproteins in human arteriosclerotic tissue. Arterioscler Thromb 1993;13:133–46. 10.1161/01.ATV.13.1.133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li W, Yuan XM. Increased expression and translocation of lysosomal cathepsins contribute to macrophage apoptosis in atherogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2004;1030:427–33. 10.1196/annals.1329.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sukhova GK, Shi GP, Simon DI et al. Expression of the elastolytic cathepsins S and K in human atheroma and regulation of their production in smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest 1998;102:576–83. 10.1172/JCI181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cicha I, Worner A, Urschel K et al. Carotid plaque vulnerability: a positive feedback between hemodynamic and biochemical mechanisms. Stroke 2011;42:3502–10. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.627265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan XM, Osman E, Miah S et al. p53 expression in human carotid atheroma is significantly related to plaque instability and clinical manifestations. Atherosclerosis 2010;210:392–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2009.11.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Platt MO, Ankeny RF, Jo H. Laminar shear stress inhibits cathepsin L activity in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006;26:1784–90. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000227470.72109.2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu J, Sukhova GK, Yang JT et al. Cathepsin L expression and regulation in human abdominal aortic aneurysm, atherosclerosis, and vascular cells. Atherosclerosis 2006;184:302–11. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.05.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lv BJ, Lindholt JS, Wang J et al. Plasma levels of cathepsins L, K, and V and risks of abdominal aortic aneurysms: a randomized population-based study. Atherosclerosis 2013;230:100–5. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.05.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldman AS, Banyard J, Wu CL et al. Cystatin B as a tissue and urinary biomarker of bladder cancer recurrence and disease progression. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:1024–31. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gashenko EA, Lebedeva VA, Brak IV et al. Evaluation of serum procathepsin B, cystatin B and cystatin C as possible biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Int J Circumpolar Health 2013;72 10.3402/ijch.v72i0.21215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Trinkaus M, Vranic A, Dolenc VV et al. Cathepsins B and L and their inhibitors stefin B and cystatin C as markers for malignant progression of benign meningiomas. Int J Biol Markers 2005;20:50–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalioti MD, Antonarakis SE, Scott HS. The epilepsy, the protease inhibitor and the dodecamer: progressive myoclonus epilepsy, cystatin b and a 12-mer repeat expansion. Cytogenet Genome Res 2003;100:213–23. doi:72857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darmanis S, Nong RY, Vanelid J et al. ProteinSeq: high-performance proteomic analyses by proximity ligation and next generation sequencing. PLoS ONE 2011;6:e25583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vetvicka V, Fusek M. Procathepsin D as a tumor marker, anti-cancer drug or screening agent. Anticancer Agents Med Chem 2012;12:172–5. 10.2174/187152012799014904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poole AR, Hembry RM, Dingle JT et al. Secretion and localization of cathepsin D in synovial tissues removed from rheumatoid and traumatized joints. An immunohistochemical study. Arthritis Rheum 1976;19:1295–307. 10.1002/art.1780190610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cataldo AM, Nixon RA. Enzymatically active lysosomal proteases are associated with amyloid deposits in Alzheimer brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990;87:3861–5. 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fach EM, Garulacan LA, Gao J et al. In vitro biomarker discovery for atherosclerosis by proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics 2004;3:1200–10. 10.1074/mcp.M400160-MCP200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vivanco F, Mas S, Darde VM et al. Vascular proteomics. Proteomics Clin Appl 2007;1:1102–22. 10.1002/prca.200700190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duran MC, Martin-Ventura JL, Mohammed S et al. Atorvastatin modulates the profile of proteins released by human atherosclerotic plaques. Eur J Pharmacol 2007;562:119–29. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.01.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berglund G, Elmstahl S, Janzon L et al. The Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. Design and feasibility. J Intern Med 1993;233:45–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1993.tb00647.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hedblad B, Nilsson P, Janzon L et al. Relation between insulin resistance and carotid intima-media thickness and stenosis in non-diabetic subjects. Results from a cross-sectional study in Malmo, Sweden. Diabet Med 2000;17:299–307. 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2000.00280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hlebowicz J, Persson M, Gullberg B et al. Food patterns, inflammation markers and incidence of cardiovascular disease: the Malmo Diet and Cancer study. J Intern Med 2011;270:365–76. 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wirfalt E, Hedblad B, Gullberg B et al. Food patterns and components of the metabolic syndrome in men and women: a cross-sectional study within the Malmo Diet and Cancer cohort. Am J Epidemiol 2001;154:1150–9. 10.1093/aje/154.12.1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Assarsson E, Lundberg M, Holmquist G et al. Homogenous 96-plex PEA immunoassay exhibiting high sensitivity, specificity, and excellent scalability. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e95192 10.1371/journal.pone.0095192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feron D, Begu-Le Corroller A, Piot JM et al. Significant lower VVH7-like immunoreactivity serum level in diabetic patients: evidence for independence from metabolic control and three key enzymes in hemorphin metabolism, cathepsin D, ACE and DPP-IV. Peptides 2009;30:256–61. 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hamed EA, Zakary MM, Abdelal RM et al. Vasculopathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus: role of specific angiogenic modulators. J Physiol Biochem 2011;67:339–49. 10.1007/s13105-011-0080-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhou H, Xiao Y, Li R et al. Quantitative analysis of secretome from adipocytes regulated by insulin. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41:910–21. 10.1093/abbs/gmp085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grimm S, Horlacher M, Catalgol B et al. Cathepsins D and L reduce the toxicity of advanced glycation end products. Free Radic Biol Med 2012;52:1011–23. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.12.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowak C, Sundstrom J, Gustafsson S et al. Protein biomarkers for insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes risk in two large community cohorts. Diabetes 2016;65:276–84. 10.2337/db15-0881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rivera LE, Colon K, Cantres-Rosario YM et al. Macrophage derived cystatin B/cathepsin B in HIV replication and neuropathogenesis. Curr HIV Res 2014;12:111–20. 10.2174/1570162X12666140526120249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takahashi H, Ishidoh K, Muno D et al. Cathepsin L activity is increased in alveolar macrophages and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of smokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1993;147(6 Pt 1):1562–8. 10.1164/ajrccm/147.6_Pt_1.1562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang JC, Yoo OH, Lesser M. Cathepsin D activity is increased in alveolar macrophages and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of smokers. Am Rev Respir Dis 1989;140:958–60. 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bracke K, Cataldo D, Maes T et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-12 and cathepsin D expression in pulmonary macrophages and dendritic cells of cigarette smoke-exposed mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 2005;138:169–79. 10.1159/000088439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barderas MG, Darde VM, De la Cuesta F et al. Proteomic analysis of circulating monocytes identifies cathepsin D as a potential novel plasma marker of acute coronary syndromes. Clin Med 2008;2:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taleb S, Lacasa D, Bastard JP et al. Cathepsin S, a novel biomarker of adiposity: relevance to atherogenesis. FASEB J 2005;19:1540–2. 10.1096/fj.05-3673fje [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Magnusson M, Hedblad B, Engstrom G et al. High levels of cystatin C predict the metabolic syndrome: the prospective Malmo Diet and Cancer Study. J Intern Med 2013;274:192–9. 10.1111/joim.12051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]