Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the national prevalence of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) in the adult Portuguese population and to determine their impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), physical function, anxiety and depression.

Methods

EpiReumaPt is a national health survey with a three-stage approach. First, 10 661 adult participants were randomly selected. Trained interviewers undertook structured face-to-face questionnaires that included screening for RMDs and assessments of health-related quality of life, physical function, anxiety and depression. Second, positive screenings for ≥1 RMD plus 20% negative screenings were invited to be evaluated by a rheumatologist. Finally, three rheumatologists revised all the information and confirmed the diagnoses according to validated criteria. Estimates were computed as weighted proportions, taking the sampling design into account.

Results

The disease-specific prevalence rates (and 95% CIs) of RMDs in the adult Portuguese population were: low back pain, 26.4% (23.3% to 29.5%); periarticular disease, 15.8% (13.5% to 18.0%); knee osteoarthritis (OA), 12.4% (11.0% to 13.8%); osteoporosis, 10.2% (9.0% to 11.3%); hand OA, 8.7% (7.5% to 9.9%); hip OA, 2.9% (2.3% to 3.6%); fibromyalgia, 1.7% (1.1% to 2.1%); spondyloarthritis, 1.6% (1.2% to 2.1%); gout, 1.3% (1.0% to 1.6%); rheumatoid arthritis, 0.7% (0.5% to 0.9%); systemic lupus erythaematosus, 0.1% (0.1% to 0.2%) and polymyalgia rheumatica, 0.1% (0.0% to 0.2%). After multivariable adjustment, participants with RMDs had significantly lower EQ5D scores (β=−0.09; p<0.001) and higher HAQ scores (β=0.13; p<0.001) than participants without RMDs. RMDs were also significantly associated with the presence of anxiety symptoms (OR=3.5; p=0.006).

Conclusions

RMDs are highly prevalent in Portugal and are associated not only with significant physical function and mental health impairment but also with poor HRQoL, leading to more health resource consumption. The EpiReumaPt study emphasises the burden of RMDs in Portugal and the need to increase RMD awareness, being a strong argument to encourage policymakers to increase the amount of resources allocated to the treatment of rheumatic patients.

Keywords: Epidemiology, Low Back Pain, Fibromyalgis/Pain Syndromes, Osteoarthritis, Spondyloarthritis

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMD) are among the most common chronic non-communicable diseases.

What does this study add?

EpiReumaPt is the first population-based study on rheumatic diseases in Portugal and we demonstrated that low back pain and osteoarthritis are the two most prevalent RMD.

We have used the new ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA and the ASAS criteria for SpA and found a prevalence of 0.7% for RA and 1.6% for SpA with similar proportion of males and females with the disease.

RMDs patients have poorer quality of life, higher health consumption and significant mental health impairment as compared to non-RMDs subjects.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

EpiReumaPt study emphasizes the burden of RMDs in Portugal and the need to increase RMD awareness.

Introduction

Rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) are among the most common chronic non-communicable diseases. They are the leading cause of disability in developed countries, and consume a large amount of health and social resources.1–3 So far, comparative factors on the impact on health-related quality of life (HRQoL), physical function and mental health status between RMD and non-RMD participants, have been unknown.4 5

The prevalence of RMDs has been determined in several countries,6–13 however, epidemiological data in Portugal are scarce.14–16 EpiReumaPt is a national health-survey conducted to estimate the prevalence of hand, knee and hip osteoarthritis (OA), low back pain (LBP), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), fibromyalgia (FM), gout, spondyloarthritis (SpA), periarticular disease (PD), systemic lupus erythaematosus (SLE), polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR) and osteoporosis (OP), in the adult Portuguese population. Another aim was to assess the burden of RMDs by determining their impact on HRQoL, physical function and mental health. Both aims address the needs and objectives identified in a recent governmental initiative—the National Program Against Rheumatic diseases.17

Methods

The study protocol has been previously published,18 as has a separate manuscript extensively describing the methodological details of the project.19 An outline of the methodology is presented below.

Setting

Portugal is a southwestern European country, including the mainland and the Autonomous Regions of Azores and Madeira. According to a census performed in 2011, Portugal has a resident population of 10 562 178 inhabitants,20 of whom 8 657 240 are adults.18 21

Study population

EpiReumaPt is a national, cross-sectional and population-based study. The study population was composed of adults (≥18 years old) who were non-institutionalised and living in private households in the Mainland and the Islands (Azores and Madeira). Exclusion criteria were: residents in hospitals, nursing homes and military institutions or prisons, and individuals unable to speak Portuguese or unable to complete the questionnaires.21

Sampling

Participants were selected through a process of multistage random sampling. The sample was stratified according to the Portuguese Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS II; seven territorial units: Norte, Centro, Alentejo, Algarve, Lisboa e Vale do Tejo, Madeira and Azores) and the size of the population (<2000; 2000–9999; 10 000–19 999; 20 000–99 999; and ≥100 000 inhabitants).

Recruitment

Recruitment took place between September 2011 and December 2013. EpiReumaPt involved a three-stage approach. First, candidate households were selected using a random route process. The adults with permanent residence in the selected household with the most recently completed birthday were recruited (one adult per household). Trained interviewers undertook structured face-to-face questionnaires in participants’ households, collecting a vast number of variables (sociodemographic, socioeconomic, HRQoL (EQ-5D-3L), physical function (HAQ), anxiety and depression symptoms, lifestyle habits, chronic non-communicable diseases, healthcare resources utilisation) and performing a screening for RMDs. Questions were asked about several rheumatic symptoms and an algorithm for the screening of each RMD was applied. An individual was considered to have a positive screening if the subject mentioned a previously known RMD, if any one of the specific disease algorithms (covering disease characteristic and respective signs and symptoms) in the screening questionnaires was positive, or if the subject reported muscle, vertebral or peripheral joint pain in the previous 4 weeks. The overall performance of the screening algorithm was evaluated (the gold standard was considered to be the final diagnosis after revision, see phase 3) and the overall sensitivity of the screening questionnaire for RMDs was 98%, with a specificity of 22%. The positive predictive value was 85% and the negative predictive value was 71%.21

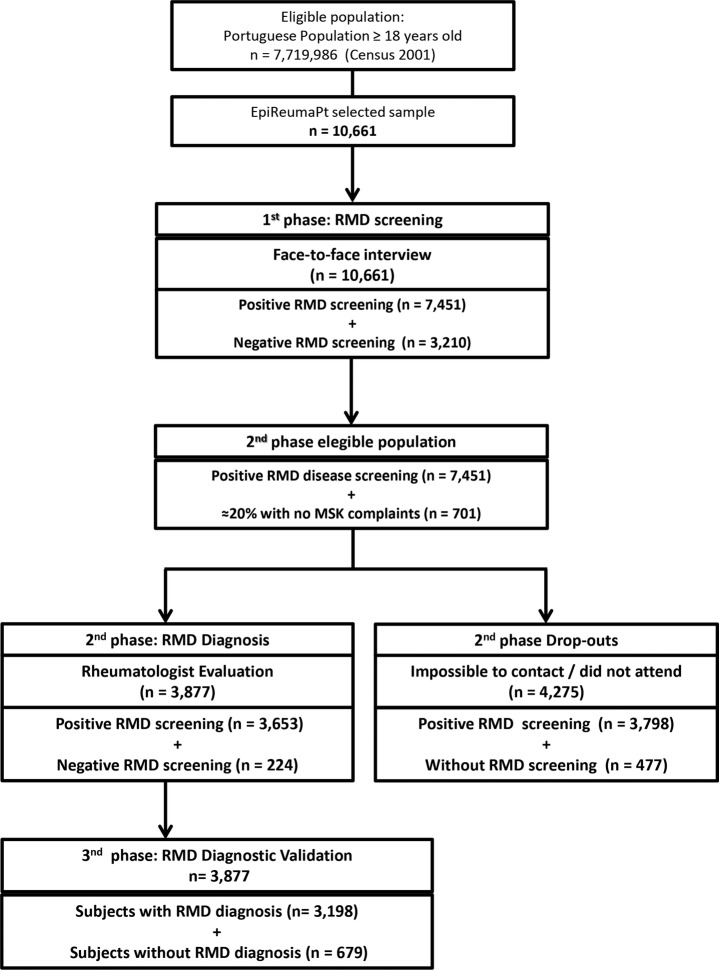

Second, all participants who screened positive for at least one RMD plus 20% of individuals with no rheumatic symptoms (negative screening) were invited for a structured evaluation by a rheumatologist at the local primary care centre. Finally, a team of three experienced rheumatologists revised all the clinical, laboratorial and imaging data, and confirmed the diagnoses according to validated criteria (figure 1).21

Figure 1.

Flowchart of recruitment in the EpiReumaPt Study. RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease; MSK, musculoskeletal disease.

Measurements

In the first phase of EpiReumaPt, participants were asked about their sociodemographic data (age, gender, ethnicity, education, marital status), socioeconomic profile (measures of wealth, household income, current professional status) and lifestyle habits (alcohol, tobacco and coffee intake, physical exercise). Information on work status was also collected. Healthcare resource consumption data were collected through the number and type of outpatient clinic visits, hospitalisations, homecare assistance and other needs for healthcare services in the previous 12 months.

To evaluate generic HRQoL, we used the Portuguese validated version of the European Quality of Life questionnaire, five dimensions, three levels (EQ-5D-3L).22 23 Physical function was assessed by the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ).24 Anxiety and depression symptoms, as aspects of mental health, were assessed by the Portuguese validated version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).25 HADS is divided into an Anxiety subscale (HADS-A) and a Depression subscale (HADS-D), both containing seven intermingled items. We also assessed anthropometric data (self-reported weight and height) and self-reported chronic diseases (high cholesterol, high blood pressure, allergies, gastrointestinal disease, mental disease, cardiac disease, diabetes, thyroid and parathyroid disease, urolithiasis, pulmonary disease, hyperuricaemia, cancer, neurological disease, hypogonadism). Information regarding pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies was also collected.

In the second phase of EpiReumaPt, thorough history-taking and physical examination were performed. Previous diagnoses of RMDs and current medications were also assessed.21

Case definition

The presence of a RMD was considered if a subject, after the clinical appointment of the second phase, had a positive expert opinion combined with the fulfilment of validated classification criteria to establish a diagnosis of knee OA, hip OA, hand OA, FM, SLE, gout, RA, SpA or PMR.21 We used the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for knee OA,26 hip OA,27 hand OA,28 FM,29 SLE30 and gout;31 the ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (ACR/EULAR) criteria for RA;32 the Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) criteria for axial and peripheral SpA;33–35 and the Bird criteria for PMR.36

PD was defined as a regional pain syndrome affecting muscles, tendons, bursas or periarticular soft tissues, with or without evidence of joint or bone involvement. The following PDs were specifically investigated: tenosynovitis, adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder, enthesopathies, bursitis, palmar or plantar fasciitis and carpal or tarsal tunnel syndrome present at the time of the assessment. The diagnosis was established based on expert opinion in the second phase of the study.

OP was defined by the clinical decision of the rheumatologist who observed the subject in the second phase of the study based on the presence of at least one of the following: previous fragility fracture, previous OP diagnosis, current OP treatment or fulfilment of the WHO criteria37 when axial dual energy X-ray absorptiometry was available.

LBP was defined solely by self-report and clinical history.

Statistical analysis

Prevalence estimates for RMDs were computed as weighted proportions, in order to take into account the sampling design.21

Participants with and without RMDs were compared. Univariable analyses were first performed considering the study design. Multivariate regression models were used to assess the differences between individuals with and without RMDs, regarding: HRQoL and physical function (EQ5D and HAQ), mental health (presence of symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A ≥11 vs <11), presence of symptoms of depression (HADS-D ≥11 vs <11)25) and health resources consumption (number of medical visits (general practitioner, rheumatologist, orthopaedic surgeon and any other specialists), and home care in the previous 12 months (yes/no), hospitalisations in the previous 12 months (yes/no), early retirement due to disease (yes/no), absence from work due to disease in the previous 12 months (yes/no) and number of days of absence). Significantly different variables in the univariable analysis were included in the multivariable model. In order to adjust the differences between groups, the following potential confounders were included in the model: age, gender, NUTS II, education level, employment status, household income, alcohol intake, current smoking, physical exercise, body mass index (BMI), physical exercise and number of comorbidities.

To assess the independent relationship of each RMD with disability (HAQ), HRQoL (EQ5D), presence of symptoms of anxiety and presence of symptoms of depression, four multivariable regression models were performed. For the first two outcomes—continuous variables—linear regression was used; and for the last two—dichotomous outcomes—logistic regression was performed. Multivariable models were constructed using a backward selection method. The following independent variables were tested: age, gender, NUTS II, years of education, work status, BMI, alcohol intake, current smoking, regular physical activity and number of comorbidities. All RMDs were included in the models and were forced to stay there. For the models with HAQ and EQ5D, the presence of symptoms of anxiety or depression was also considered. Possible interactions between each RMD and gender and age were tested for the four outcomes.

Significance level was set at 0.05. All analyses were weighted and performed using STATA IC V.12 (StataCorp, 2011. Stata Statistical Software: Release 12. College Station, Texas, USA: StataCorp LP).

Ethical issues

EpiReumaPt was performed according to the principles established by the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was reviewed and approved by the National Committee for Data Protection (Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados) and by the NOVA Medical School Ethics Committee. All participants provided informed consent to participate in all phases of the study.18 Further details of ethical issues of EpiReumaPt have been described elsewhere.19

Results

Prevalence of RMDs in the Portuguese adult Population

The EpiReumaPt population did not differ from the Portuguese population (table 1).20 38 In the EpiReumaPt study, 21.2% (95% CI 19.9% to 22.5%) of the Portuguese population self-reported a RMD. During the second phase of the study, we observed 3877 participants and detected 1532 new RMD diagnoses; 2670 individuals were found to have more than one RMD. Moreover, of the 3877 participants evaluated in the second phase, only 85 (9.6%) previously reporting a RMD had no identifiable target disease.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and health related characteristics of the adult Portuguese population: EpiReumaPt population (first and second phase) and Census 2011 population (Portuguese population)

| Demographic characteristics | First phase study population n=10 661 |

Second phase study population n=3877 |

CENSUS 2011 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (female) | 6551 (52.6%) | 2630 (52.5%) | 4 585 118 (53.0%) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| 18–29 | 1182 (22.1%) | 190 (21.0%) | 1 470 782 (17.0%) |

| 30–39 | 1511 (18.8%) | 403 (19.3%) | 1 598 250 (18.5%) |

| 40–49 | 1906 (17.3%) | 680 (18.2%) | 1 543 392 (17.8%) |

| 50–59 | 1801 (14.8%) | 818 (14.7%) | 1 400 011(16.2%) |

| 60–69 | 1915 (12.9%) | 914 (13.4%) | 1 186 442 (13.7%) |

| 70–74 | 849 (5.8%) | 376 (5.3%) | 496 438 (5.7%) |

| ≥75 | 1497 (8.4%) | 496 (8.0%) | 961 925 (11.1%) |

| Ethnicity/race | |||

| Caucasian | 10 342 (96.0%) | 3786 (93.3%) | No comparable data |

| Black | 221 (3.4%) | 64 (6.1%) | |

| Asian | 8 (0.1%) | 2 (0.0%) | |

| Gipsy | 20 (0.3%) | 3 (0.1%) | |

| Other | 38 (0.3%) | 13 (0.5%) | |

| Education level (years) | |||

| >12 | 1764 (20.4%) | 508 (21.1%) | 1 741 567 (20.1%) |

| 10–12 | 1920 (23.8%) | 575 (23.2%) | 1 560 958 (18.0%) |

| 5–9 | 2175 (22.6%) | 775 (22.4%) | 2 134 401 (24.6%) |

| 0–4 | 4726 (33.2%) | 1997 (33.4%) | 3 239 724 (37.4%) |

| NUTS II | |||

| Norte | 3122 (34.9%) | 1050 (37.2%) | 3 007 823 (34.7%) |

| Centro | 1997 (22.8%) | 856 (19.8%) | 1 938 815 (22.4%) |

| Lisboa | 2484 (26.7%) | 708 (29.6%) | 2 300 053 (26.6%) |

| Alentejo | 669 (7.3%) | 273 (5.8%) | 633 691 (7.3%) |

| Algarve | 352 (3.8%) | 144 (3.1%) | 370 704 (4.3%) |

| Azores | 1029 (2.2%) | 420 (2.3%) | 192 357 (2.2%) |

| Madeira | 1008 (2.3%) | 426 (2.2%) | 213 797 (2.5%) |

NUTS II, Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (Norte, Centro, Alentejo, Algarve, Lisboa, Madeira and the Azores).

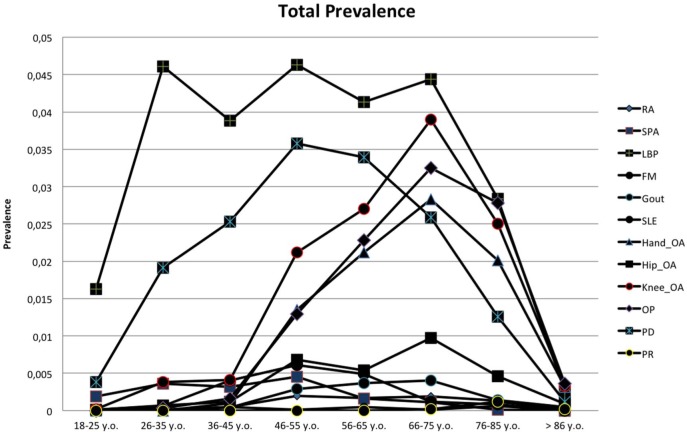

The prevalence of each RMD, overall and stratified by gender, and the estimated number of patients in the Portuguese population are shown in table 2. The RMD with the highest prevalence in Portugal was LBP (26.4%; 95% CI 23.3% to 29.5%), significantly more frequent in women than in men (29.6% vs 22.8%; p=0.040) (table 2). LBP increased with age and its prevalence was highest in the 46–55-year age group (27.7%; 95% CI 23.1% to 32.4%) (figure 2). PD was also a frequent RMD with an overall prevalence of 15.8% (95%CI 13.5% to 18.0%) and women were also significantly more affected than men (19.1% vs 12.0%; p=0.005). This RMD had the highest prevalence in the working-age population (46–55 years) (21.5%; 95% CI 17.4 to 25.5%) (figure 2). OA was also common among Portuguese individuals; particularly knee OA, with a prevalence of 12.4% (95% CI 11.0% to 13.8%). Of note, the combined prevalence of hip and/or knee and/or hand OA in Portugal is 19.1% (95% CI 17.1 to 21.1%). Noteworthy, gout had an overall prevalence of 1.3% (95% CI 1.0% to 1.6%) (table 2). The age stratum with the highest gout prevalence corresponded to the elderly (>85 years old) with a 3.2% prevalence (95% CI 2.0% to 4.4%) (figure 2). As expected, men had the highest gout prevalence (2.6% vs 0.1% in women, p<0.001). Moreover, 22.2% (95% CI 8.2 to 36.2) of gout patients had poliarticular disease and 11.0% had chronic tophaceous gout. The mean number of gout attacks in the 12 months preceding the clinical evaluation was 2.0±1.7.

Table 2.

Prevalence of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases (RMDs) in Portugal, overall and stratified by gender

| Total prevalence (95% CI) n=3877 |

Women (95% CI) n=2630 |

Men (95% CI) n=1247 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Low back pain (n=1393) | 26.4% (23.3% to 29.5%) | 29.6% (25.8% to 33.5%) | 22.8% (17.9% to 27.8%) |

| Periarticular disease (n=929) | 15.8% (13.5% to 18.0%) | 19.1% (16.2% to 22.0%) | 12.0% (8.4% to 15.6%) |

| Knee osteoarthritis (n=981) | 12.4% (11.0% to 13.8%) | 15.8% (13.7% to 18.0%) | 8.6% (6.9% to 10.3%) |

| Osteoporosis (n=858) | 10.2% (9.00% to 11.3%) | 17.0% (14.7% to 19.2%) | 2.6% (1.9% to 3.4%) |

| Hand osteoarthritis (n=625) | 8.7% (7.5% to 9.9%) | 13.8% (11.6% to 15.9%) | 3.2% (2.2% to 4.1%) |

| Hip osteoarthritis (n=199) | 2.9% (2.3% to 3.6%) | 3.0% (2.3% to 3.7%) | 2.9% (1.7% to 4.1%) |

| Fibromyalgia n=149) | 1.7% (1.3% to 2.1%) | 3.1% (2.4% to 3.9%) | 0.0% (−0.0% to 0.2%) |

| Spondyloarthritis (n=92) | 1.6% (1.2% to 2.1%) | 2.0% (1.3% to 2.7%) | 1.2% (0.7% to 1.8%) |

| Gout (n=92) | 1.3% (1.0% to 1.6%) | 0.1% (−0.0% to 0.2%) | 2.6% (1.9% to 3.3%) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (n=61) | 0.7% (0.5% to 0.9%) | 1.2% (0.8% to 1.5%) | 0.3% (0.1% to 0.4%) |

| SLE (n=13) | 0.1% (0.1% to 0.2%) | 0.2% (0.1% to 0.4%) | 0.0% (−0.0% to 0.1%) |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica (n=8) | 0.1% (0.0% to 0.2%) | 0.13% (0.0% to 0.2%) | 0.1% (−0.0% to 0.2%) |

The sample was calculated considering a minimum prevalence of 0.5%.18 For rare diseases the estimated number of Portuguese participants with the disease could be overestimated.

RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythaematosus.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of RMDs, stratified by age group. RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Regarding inflammatory rheumatic diseases, SpA had the highest prevalence in the adult population (1.6%; 95% CI 1.2% to 2.0%), with 51.8% of cases being axial SpA. We found no significant gender predominance in SpA (p=0.094). Among SpA subtypes according to the classical nomenclature, undifferentiated SpA accounted for 44.3% of cases, ankylosing spondylitis (AS) 29.6%, psoriatic arthritis 18.7% and SpA associated with inflammatory bowel disease 12.0%. These results correspond to a national prevalence rate of 0.7% (95% CI 0.4% to 1.0%) for undifferentiated SpA, 0.5% (95% CI 0.3% to 0.7%) for AS, 0.3% (0.1% to 0.5%) for psoriatic arthritis and 0.2% (0.0% to 0.4%) for SpA associated with inflammatory bowel disease. Finally, the prevalence of RA was 0.7% (95% CI 0.5% to 0.9%).

Participants with RMDs had significantly lower HRQoL, physical function and mental health and consumed more healthcare resources

Regarding HRQoL, we found that participants with RMD had significantly lower EQ5D scores (β=−0.09; p<0.001) when compared to participants without RMD, adjusted for demographic factors, socioeconomic factors, lifestyle and comorbidities. Furthermore, patients with RMD had significantly higher disability (HAQ score) (β=0.13; p<0.001).

We also found that, in participants with RMD, there was a significantly higher prevalence of anxiety symptoms (OR=3.5; p=0.006) but no significant differences were found regarding depressive symptoms (OR=1.9; p=0.173) (table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of sociodemographic, socioeconomic, health status and health resources consumption between participants with and without RMD: adjusted analysis

| HRQoL and physical function | RMD n=3195 | Non-RMD n=682 |

β estimates | 95% CI | Adjusted p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ5D (0–1) | 0.7±0.3 | 0.9±0.1 | −0.09 | (−0.13 to −0.05) | <0.001* | |

| HAQ (0–3) | 0.4±0.7 | 0.1±0.2 | 0.13 | (0.08 to 0.17) | <0.001* | |

| Mental health | RMD | Non-RMD | OR | 95% CI | Adjusted p value | |

| Anxiety (yes vs no) | 600 (16.7%) | 63 (5.3%) | 3.5 | (1.4 to 8.0) | 0.006* | |

| Depression (yes vs no) | 349 (8.3%) | 29 (1.3%) | 1.9 | (0.8 to 4.6) | 0.173 | |

| Healthcare resources consumption | RMD | Non-RMD | OR | 95% CI | Adjusted p value | |

| Physician visits in the past 12 months | 0.010* | |||||

| General practitioners | 2661 (78.8%) | 502 (71.5%) | 0.5 | (0.3 to 0.8) | <0.001* | |

| Rheumatology visits | 206 (4.6%) | 11 (1.0%) | 30.5 | (7.4 to 126.2) | 0.010* | |

| Orthopaedic visits | 475 (14.9%) | 46 (6.5%) | 3.2 | (1.3 to 7.8) | 0.825 | |

| Other visits | 1758 (57.1%) | 347 (53.5%) | 0.9 | (0.6 to 1.5) | ||

| Healthcare resources consumption | RMD | Non-RMD | β estimates | 95% CI | Adjusted p value | |

| Number of physician appointments in the past 12 months | ||||||

| General practitioners | 2.5±5.9 | 4.0±19.0 | −4.01 | (−11.37 to 3.34) | 0.285 | |

| Rheumatology appointments | 0.1±0.8 | 0.0±0.1 | 0.08 | (0.05 to 0.11) | <0.001* | |

| Orthopaedic appointments | 0.4±1.4 | 0.1±0.4 | 0.27 | (0.10 to 0.43) | 0.002* | |

| Other appointments | 1.9±8.0 | 1.5±1.5 | 0.01 | (−0.47 to 0.50) | 0.961 | |

| Healthcare resources consumption | RMD | Non-RMD | OR | 95% CI | Adjusted p value | |

| Home care in the past 12 months | 100 (2.7%) | 5 (0.1%) | 13.2 | (2.7 to 63.6) | 0.001* | |

| Hospitalisations in the past 12 months | 324 (11.4%) | 53 (5.5%) | 2.5 | (1.1 to 5.8) | 0.027* | |

| Early retirement due to disease | 488 (30.9%) | 33 (22.0%) | 2.3 | (0.9 to 6.0) | 0.101 | |

| Absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months | 323 (29.9%) | 76 (24.8%) | 1.7 | (0.8 to 3.5) | 0.163 | |

| Healthcare resources consumption | RMD | Non-RMD | β estimates | 95% CI | Adjusted p value | |

| Number of days absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months | 31.5±83.9 | 22.5±14.1 | 14.11 | (−4.72 to 32.94) | 0.141 | |

Sample size is not constant due to missing data in RMD: EQ5D (n=3168), Early retirement due to disease (n=1419), absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months (n=1010), number of days absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months (n=318).

Non-RMD: EQ5D (n=678), Early retirement due to disease (n=142), absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months (n=359), number of days absent from work due to disease in the past 12 months (n=75).

p Values were adjusted for age, gender, Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (North, Centre, Alentejo, Algarve, Lisbon, Madeira and the Azores), years of education, work status, household income, alcohol intake, physical exercise, Body Mass Index and number of comorbidities. For continuous variables, a multivariable regression was used to assess the differences between the groups (individuals with Rheumatic Diseases and those without Rheumatic Diseases). The estimated values were obtained considering study design.

*Adjusted p values <0.05.

EQ5D, European Quality of Life questionnaire five dimensions three levels; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Considering healthcare resource consumption (table 3), patients with RMD had been more often hospitalised and had more homecare support needs in the previous 12 months when compared to participants without any RMD (OR=2.5, p=0.027 and OR=13.2, p=0.001, respectively). Finally, we found no differences between the two groups regarding sick leave or early retirement due to disease (table 3).

Disease-specific associations with worse HRQoL and higher disability

Several RMDs were significantly and independently associated with worse QoL in the Portuguese population. By decreasing order of effect, PMR (β=−0.33; p=0.027), RA (β=−0.13; p=0.001), FM (β=−0.10; p<0.001), LBP (β=−0.07; p<0.001), knee OA (β=−0.06; p<0.001) and PD (β=−0.04; p=0.029) were associated with worse QoL. Moreover, participants retired or on sick leave (β=−0.04; p=0.016) and those with a higher number of comorbidities (β=−0.03; p<0.001) were also associated with worse QoL. The presence of anxiety and depressive symptoms (HADS≥11) were also associated with worse QoL (β=−0.14; p<0.001 and β=−0.14; p<0.001, respectively). On the other hand, alcohol consumption was significantly associated with better QoL (β=0.045; p<0.001) (table 4).

Table 4.

Factors associated with health-related quality of life (EQ5D) and physical function (HAQ) considering each RMD as a variable of interest: multivariable models

| Demographic characteristics | EQ5D |

HAQ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient (95% CI) | p Value | β coefficient (9 5%CI) | p Value | |

| Gender (female) | −0.03 (−0.06 to 0.00) | 0.058 | 0.11 (0.07 to 0.15) | <0.001* |

| Age (years) | 0.00 (−0.0 to 0.01) | 0.902 | 0.00 (−0.00 to 0.00) | 0.857 |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight vs normal | 0.09 (−0.01 to 0.16) | 0.021* | −0.02 (−0.16 to 0.12) | 0.802 |

| Overweight vs normal | 0.03 (−0.00 to 0.52) | 0.067 | −0.00 (−0.04 to 0.04) | 0.975 |

| Obese vs normal | 0.01 (−0.02 to 0.04) | 0.526 | −0.08 (0.02 to 0.14) | 0.005* |

| Years of education | −0.01 (−0.0 to 0.00) | 0.788 | −0.01 (−0.02 to −0.00) | 0.002* |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed vs retired or sick leave | −0.04 (−0.09 to −0.00) | 0.046* | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.21) | <0.001* |

| Employed vs unemployment | −0.00 (−0.04 to 0.05) | 0.946 | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.10) | 0.170 |

| NUTS II | ||||

| Norte vs Lisboa | 0.0 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.832 | 0.03 (−0.01 to 0.08) | 0.168 |

| Centro vs Lisboa | 0.0 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.777 | 0.04 (−0.02 to 0.10) | 0.167 |

| Alentejo vs Lisboa | 0.02 (−0.2 to 0.05) | 0.414 | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.18) | 0.001* |

| Algarve vs Lisboa | 0.04 (−0.00 to 0.09) | 0.078 | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.07) | 0.836 |

| Azores vs Lisboa | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.05) | 0.572 | −0.00 (−0.05 to 0.05) | 0.938 |

| Madeira vs Lisboa | 0.01 (−0.03 to 0.04) | 0.763 | 0.11 (0.02 to 0–19) | 0.011* |

| Number of comorbidities (0–15) | −0.03 (−0.04 to −0.03) | <0.001* | 0.06 (0.05 to 0.08) | <0.001* |

| Life-style habits | ||||

| Alcohol intake (yes/no) | 0.05 (0.02 to 0.07) | 0.001* | −0.06 (−0.10 to −0.01) | 0.023* |

| Regular physical exercise (yes/no) | 0.02 (−0.01 to 0.05) | 0.152 | −0.03 (−0.07 to 0.01) | 0.139 |

| Mental disorders | ||||

| Anxiety (yes/no) | −0.14 (−0.20 to −0.08) | <0.001* | 0.15 (0.07 to 0.22) | <0.001* |

| Depression (yes/no) | −0.14 (−0.19 to −0.09) | <0.001* | 0.32 (0.20 to 0.44) | <0.001* |

| RMD diagnosis | ||||

| Low back pain (yes/no) | −0.07 (−0.10 to −0.04) | <0.001* | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.13) | <0.001* |

| Periarticular disease (yes/no) | −0.04 (−0.08 to −0.01) | 0.016* | 0.06 (0.01 to 0.11) | 0.019* |

| Knee osteoarthritis (yes/no) | −0.06 (−0.09 to −0.03) | <0.001* | 0.11 (0.04 to 0.18) | 0.002* |

| Osteoporosis (yes/no) | −0.01 (−0.04 to 0.02) | 0.676 | 0.08 (0.01 to 0.15) | 0.033* |

| Hand osteoarthritis (yes/no) | −0.00 (−0.04 to 0.03) | 0.831 | −0.00 (−0.08 to 0.07) | 0.903 |

| Hip osteoarthritis (yes/no) | −0.05 (−0.10 to 0.01) | 0.083 | −0.30 (−0.70 to 0.10) | 0.145 |

| Fibromyalgia (yes/no) | −0.10 (−0.16 to −0.05) | <0.001* | 0.27 (0.10 to 0.43) | <0.001* |

| Spondyloarthritis (yes/no) | −0.05 (−0.11 to 0.01) | 0.120 | 0.08 (−0.35 to 0.19) | 0.180 |

| Gout (yes/no) | 0.05 (−0.01 to 0.11) | 0.085 | −0.06 (−0.19 to 0.07) | 0.387 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (yes/no) | −0.13 (−0.21 to −0.06) | 0.001* | 0.38 (0.20 to 0.56) | <0.001* |

| SLE (yes/no) | 0.03 (−0.072 to 0.13) | 0.585 | 0.23 (−0.07 to 0.53) | 0.137 |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica (yes/no) | −0.33 (−0.63 to −0.04) | 0.027* | 1.03 (0.46 to 1.60) | <0.001* |

| Hip osteoarthritis×age | – | – | 0.01 (0.00 to 0.01) | 0.016* |

Two multivariable regression models were used: one to identify possible factors that have an impact on the HRQoL, and another to identify possible factors that have an impact on the functional capacity. The estimates were obtained considering study design.

*Adjusted p value<0.05.

BMI, body mass index; EQ5D, European Quality of Life questionnaire five dimensions three levels; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire; NUTS II, Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (North, Centre, Alentejo, Algarve, Lisbon, Madeira and the Azores); RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythaematosus.

Regarding the HAQ score, and by decreasing order of effect, PMR (β=1.03; p<0.001), RA (β=0.38; p<0.001), FM (β=0.27; p=0.001), knee OA (β=0.11; p=0.002), LBP (β=0.09; p<0.001), OP (β=0.08; p=0.033) and PD (β=0.06; p=0.019) were significantly associated with disability.

Certain characteristics, such as female gender (β=0.11; p<0.001), low educational level (β=−0.01; p=0.002) and sick leave or retirement (β=0.14; p<0.001), were significantly associated with higher HAQ scores. The number of comorbidities (β=0.06; p<0.001) and symptoms of anxiety (β=0.15; p<0.001) or depression (β=0.32; p<0.001) were also significantly associated with disability. Daily or occasional alcohol intake was significantly associated with lower HAQ scores (β=−0.06; p=0.023) (table 4).

Disease-specific associations with depression and anxiety symptoms

Several RMDs were significantly and independently associated with the presence of anxiety (HADS-A ≥11) and depressive symptoms (HADS-D ≥11) (table 5). By order of effect, FM (OR=3.4; p<0.001), SpA (OR=3.0; p=0.008) and LBP (OR=1.9; p=0.005) were significantly and independently associated with the presence of anxiety symptoms (table 5). On the other hand, PMR (OR=14.3; p=0.012), FM (OR=4.0; p=0.001) and LBP (OR=1.6; p=0.014) and knee OA (OR=1.5; p=0.047), were significantly and independently associated with the presence of depressive symptoms. SLE was significantly associated with the absence of depressive symptoms (OR=0.1; p=0.031) (table 5).

Table 5.

Factors associated with anxiety and depression symptoms (HADS) considering each RMD as a variable of interest: multivariable models

| Demographic characteristics | Anxiety |

Depression |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | p Value | OR (95% CI) | p Value | |

| Gender (female) | 3.1 (1.7 to 5.9) | 0.001* | 2.8 (1.6 to 4.9) | <0.001* |

| Age | 0.98 (0.956 to 0.997) | 0.024* | 1.03 (1.0 to 1.1) | 0.004* |

| BMI | ||||

| Underweight vs normal | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.5) | 0.183 | 0.1 (0.1 to 0.5) | 0.010* |

| Overweight vs normal | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.2) | 0.240 | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) | 0.059 |

| Obese vs normal | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.026* | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.309 |

| Years of education | 0.9 (0.86 to 0.99) | 0.027* | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.998) | 0.044* |

| Employment status | ||||

| Employed vs retired or leave | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.5) | 0.602 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.5) | 0.580 |

| Employed vs unemployment | 2.9 (1.4 to 5.9) | 0.003* | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.9) | 0.080 |

| NUTS II | ||||

| Norte vs Lisboa | 1.8 (1.0 to 3.3) | 0.035* | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 0.820 |

| Centro vs Lisboa | 1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) | 0.739 | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.7) | 0.746 |

| Alentejo vs Lisboa | 1.1 (0.6 to 2.1) | 0.791 | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.2) | 0.972 |

| Algarve vs Lisboa | 1.0 (0.5 to 2.2) | 0.972 | 2.0 (0.5 to 8.0) | 0.340 |

| Azores vs Lisboa | 1.2 (0.7 to 2.2) | 0.502 | 1.0 (0.6 to 1.8) | 0.987 |

| Madeira vs Lisboa | 1.0 (0.4 to 2.1) | 0.922 | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.1) | 0.101 |

| Number of comorbidities (0–15) | 1.5 (1.4 to 1.7) | <0.001* | 1.3 (>1.2 to 1.5) | <0.001* |

| Life style habits | ||||

| Present alcohol intake (yes/no) | 0.6 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.020* | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.505 |

| Regular physical exercise (yes/no) | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) | 0.182 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.6) | 0.001* |

| RMD diagnosis | ||||

| Low back pain (yes/no) | 1.9 (1.2 to 2.9) | 0.005* | 1.6 (1.1 to 2.4) | 0.014* |

| Periarticular disease (yes/no) | 1.1 (0.8 to 1.6) | 0.599 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.082 |

| Knee osteoarthritis (yes/no) | 0.95 (0.6 to 1.4) | 0.813 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.4) | 0.047* |

| Osteoporosis (yes/no) | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.8) | 0.344 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) | 0.745 |

| Hand osteoarthritis (yes/no) | 0.94 (0.5 to 1.6) | 0.831 | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.6) | 0.903 |

| Hip osteoarthritis (yes/no) | 0.9 (0.5 to 1.6) | 0.628 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.7) | 0.600 |

| Fibromyalgia (yes/no) | 3.4 (1.8 to 6.1) | <0.001* | 4.0 (1.8 to 8.9) | 0.001* |

| Spondyloarthritis (yes/no) | 3.0 (1.3 to 6.7) | 0.008* | 1.7 (0.5 to 5.2) | 0.365 |

| Gout (yes/no) | 1.7 (0.6 to 4.8) | 0.335 | 0.6 (0.1 to 4.8) | 0.621 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis (yes/no) | 2.0 (0.7 to 5.8) | 0.197 | 1.9 (0.8 to 4.7) | 0.155 |

| SLE (yes/no) | 1.6 (0.2 to 11.0) | 0.608 | 0.1 (0.0 to 0.8) | 0.031* |

| Polymyalgia rheumatica (yes/no) | 3.2 (0.3 to 40.1) | 0.364 | 14.3 (>1.8 to 114.3) | 0.012* |

Two logistic regression models were used: one to identify possible factors that have an impact on the presence of anxiety symptoms, and another to identify possible factors that have an impact on presence of depression symptoms. The estimated values were obtained considering study design.

*Adjusted p value<0.05.

BMI, body mass index; NUTS II, Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (North, Centre, Alentejo, Algarve, Lisbon, Madeira and the Azores); RMD, rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease; SLE, systemic lupus erythaematosus.

Discussion

EpiReumaPt has been the first large-scale epidemiological population-based study to evaluate RMDs in Portugal. In this study, we determined the prevalence of 12 target diseases (LBP, FM, OP, PD, hand, knee and hip OA, RA, SpA, SLE, gout and PMR). Moreover, we aimed to determine the impact of RMDs on physical and mental health.

We found that RMDs are highly prevalent in Portugal and that their prevalence is similar to that reported in other countries,8–11 39–43 namely our close neighbour Spain.7 However, in the EpiReumaPt study, LBP was the most prevalent RMD as opposed to other epidemiological studies9 10 12 where OA was the most prevalent disease. This finding may be due to the different methodology used in the EpiReumaPt study in which OA was considered separately according to body region (hand, knee and hip). In fact, if we consider the combined prevalence of hip and/or knee and/or hand OA, it reaches 19.1%, which is indeed similar to that reported in other epidemiological studies. Moreover, the prevalence of gout (1.3%) was higher in the EpiReumaPt study than that estimated for Europe in the Global Burden of Disease study,44 but similar to the prevalence in the UK.45 This finding may relate to the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Portugal, as a result of recent dietary changes including the decline of the Mediterranean food pattern.46

In the EpiReumaPt study, we used the new ACR/EULAR classification criteria for RA32 and the ASAS criteria for SpA,33 35 and found a prevalence of 0.7% for RA and 1.6% for SpA, with a similar proportion of males and females having the disease. Global prevalence values for SpA calculated before the introduction of the ASAS criteria were reported to be ≈1%,47 but ranged substantially from 0.001 in Japan48 to 2.5% in Northern Arctic Natives.49 In fact, the new ASAS classification criteria for axial SpA cover a larger disease spectrum, from no structural damage to advanced disease. Importantly, these criteria include not only radiographic but also MRI-detected abnormalities of the sacroiliac joints.33 To our knowledge, only one study has used the ASAS classification criteria to estimate the overall prevalence of SpA.50 Constatino et al used a large population-based cohort—the GAZEL cohort—to estimate SpA prevalence in the French population (0.43%). Unlike the study by Constantino et al, in EpiReumaPt, the use of the new criteria confirmed a higher prevalence of SpA in Portugal than that previously reported.14

Another interesting finding in our study was the high proportion of individuals presenting with typical features of one or more RMD, who did not have a previous diagnosis (1532 participants). This could be explained by the scarce number of rheumatologists in Portugal (1:100 000 inhabitants)51 and by the lack of awareness of the population to these diseases, being frequently accepted as part of the normal ageing process.

Regarding the impact of RMDs on HRQoL, physical function and mental health of the Portuguese population, we confirmed that patients with RMDs have significantly worse HRQoL and more disability when compared to participants without RMDs. We found that PMR, RA and FM were the conditions with the worst impact on function and HRQoL. When we compared those participants with and without RMDs regarding mental distress symptoms, we found a significantly higher proportion of patients with RMD with anxiety symptoms but not with depressive symptoms. This could be due to the unexpectedly low proportion of anxiety (16.7%) and depression (8.3%) symptoms among Portuguese patients with RMDs. In fact, in our study, we have shown that only LBP and FM were independently associated with anxiety as well as depressive symptoms. SpA was only associated with anxiety symptoms and PMR with depressive symptoms. In contrast, several other studies have shown higher prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms associated with several RMDs.38 52 53 One explanation could be that many of these studies were performed in a hospital environment and were not population-based studies.

The EpiReumaPt study has some limitations, for example, we used the last birthday within-unit respondent selection method for recruitment. This method has been used by many survey research organisations since the early 1980s. The advantages of this method is that it takes little time to administer, is non-intrusive and, in theory, provides a true random selection of one adult within a multiple adult household. A drawback with the birthday method is that it generates a sample with too many respondents having their birthdays close to the survey date. In EpiReumaPt, we decided to use this method because few variables that we have used are related with birthday.54 55 Moreover, we had a high dropout rate from the first phase to the second phase. In order to assure that we did not over/underestimate the disease prevalence due to eventual sample bias, we performed a detailed participation analysis considering several subject domains (demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle, healthcare resource consumption, RMD screening result and self-report of other chronic diseases), which is described elsewhere.21 Another possible study weakness is related to the definition of PD. We opted for clinical diagnosis after careful history-taking and physical evaluation. Previously structured approaches such as the upper limb MS regional syndrome schedule validated by Palmer et al56 have been used and these could have benefits particularly for epidemiological studies in which physical examination is performed by different healthcare professionals. Moreover, densitometric measurements were not included in the OP definition, which could have led to an underestimation of the prevalence. This study also has several strengths—it is the first population-based study on RMDs in Portugal, and RMDs were accessed and validated by a rheumatologist, and captured various clinical measurements that allowed addressing of the burden of these diseases.

In conclusion, in EpiReumaPt, we have demonstrated that RMDs are highly prevalent in Portugal, as in other southern European countries. Moreover, RMDs are associated not only with significant physical function and mental health impairment but also with poor HRQoL, leading to more health resource consumption. EpiReumaPt also provided valuable data to researchers, healthcare providers and patient organisations. Results of EpiReumaPt emphasise the burden of RMDs in Portugal and the need to increase RMD awareness, being a strong argument to encourage policymakers to increase the amount of resources allocated to the treatment of rheumatic patients.

Acknowledgments

The EpiReumaPt Study Group would like to acknowledge the invaluable help of Henrique de Barros, MD PhD; João Eurico da Fonseca, MD PhD; José António Pereira da Silva, MD PhD; Francisco George, MD; Rui André, MD; Luís Maurício, MD; Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Coimbra, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade do Porto, Liga Portuguesa Contra as Doenças Reumáticas, Associações de Doentes com Doença Reumática, Administrações Regionais de Saúde (Norte, Centro, Lisboa e Vale do Tejo, Alentejo e Algarve), Governo Regional da Madeira, Governo Regional dos Açores, Associação Nacional de Freguesias, Associação Nacional dos Municípios Portugueses, Câmara Municipal de Lisboa.

Footnotes

Collaborators: EpiReumaPt study group. Sociedade Portuguesa Reumatologia: Alexandra Bernardo, Alexandre Sepriano, Ana Filipa Mourão, Ana Maria Rodrigues, Ana Raposo, Ana Sofia Roxo, Anabela Barcelos, António Vilar, Armando Malcata, Augusto Faustino, Cândida Silva, Carlos Vaz, Carmo Afonso, Carolina Furtado, Catarina Ambrósio, Cátia Duarte, Célia Ribeiro, Cláudia Miguel, Cláudia Vaz, Cristina Catita, Cristina Ponte, Daniela Peixoto, Diana Gonçalves, Domingos Araújo, Elsa Sousa, Eva Mariz, Fátima Godinho, Fernando Pimentel, Filipa Ramos, Filipa Teixeira, Filipe Araújo, Filipe Barcelos, Georgina Terroso, Graça Sequeira, Guilherme Figueiredo, Helena Canhão, Herberto Jesus, Inês Cunha, Inês Gonçalves, Inês Silva, JA Pereira da Silva, Jaime Branco, Joana Abelha, Joana Ferreira, João Dias, João Eurico Fonseca, João Ramos, João Rovisco, Joaquim Pereira, Jorge Silva, José Carlos Romeu, José Costa, José Melo Gomes, José Pimentão, Lúcia Costa, Luís Inês, Luís Maurício, Luís Miranda, Margarida Coutinho, Margarida Cruz, Margarida Oliveira, Maria João Gonçalves, Maria João Salvador, Maria José Santos, Mariana Santiago, Mário Rodrigues, Maura Couto, Miguel Bernardes, Miguel Sousa, Mónica Bogas, Patrícia Pinto, Paula Araújo, Paula Valente, Paulo Coelho, Paulo Monteiro, Pedro Madureira, Raquel Roque, Renata Aguiar, Ricardo O Figueira, Rita Barros, Rita Fonseca, Romana Vieira, Rui André, Rui Leitão, Sandra Falcão, Sara Serra, Sílvia Fernandes, Sofia Pimenta, Sofia Ramiro, Susana Capela, Taciana Videira, Teresa Laura Pinto, Teresa Nóvoa, Viviana Tavares.

Contributors: JCB, SR, PMM, PL, LPdC JC, LC and HC developed the study design. JCB, HC, AMR, NG, AFM, IS, AS, FA and VT contributed substantially to data acquisition. JCB, AMR, ME, SR, PMM, SG, PSC, JMM and HC were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. JCB, AMR, SR, PMM and HC wrote the draft of this paper. All the co-authors have reviewed and made significant contributions to the paper and to its final approval.

Funding: EpiReumaPt was supported by a grant from Direcção-Geral da Saúde and was sponsored by: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Fundação Champalimaud, Fundação AstraZeneca, Abbott, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Pfizer, Roche, Servier, Bial, D3A Medical Systems, Happybrands, Centro de Medicina Laboratorial Germano de Sousa, CAL-Clínica, Galp Energia, Açoreana Seguros and individual Rheumatologists.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was reviewed and approved by the National Committee for Data Protection (Comissão Nacional de Proteção de Dados) and by the NOVA Medical School Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Badley EM, Rasooly I, Webster GK. Relative importance of musculoskeletal disorders as a cause of chronic health problems, disability, and health care utilization: findings from the 1990 Ontario Health Survey. J Rheumatol 1994;21:505–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yelin E, Callahan LF. The economic cost and social and psychological impact of musculoskeletal conditions. National Arthritis Data Work Groups. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:1351–62. 10.1002/art.1780381002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makela M, Heliovaara M, Sievers K et al. Musculoskeletal disorders as determinants of disability in Finns aged 30 years or more. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:549–59. 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90128-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T et al. EQ-5D and SF-36 quality of life measures in systemic lupus erythematosus: comparisons with rheumatoid arthritis, noninflammatory rheumatic disorders, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol 2010;37:296–304. 10.3899/jrheum.090778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Birtane M, Uzunca K, Tastekin N et al. The evaluation of quality of life in fibromyalgia syndrome: a comparison with rheumatoid arthritis by using SF-36 Health Survey. Clin Rheumatol 2007;26:679–84. 10.1007/s10067-006-0359-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra A. COPCORD—an unrecognized fountainhead of community rheumatology in developing countries. J Rheumatol 2004;31:2320–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmona L, Ballina J, Gabriel R et al. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the general population of Spain: results from a national survey. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:1040–5. 10.1136/ard.60.11.1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gabriel SE, Michaud K. Epidemiological studies in incidence, prevalence, mortality, and comorbidity of the rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Res Ther 2009;11:229 10.1186/ar2669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pelaez-Ballestas I, Sanin LH, Moreno-Montoya J et al. Epidemiology of the rheumatic diseases in Mexico. A study of 5 regions based on the COPCORD methodology. J Rheumatol Suppl 2011;86:3–8. 10.3899/jrheum.100951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lawrence RC, Felson DT, Helmick CG et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:26–35. 10.1002/art.23176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:15–25. 10.1002/art.23177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anagnostopoulos I, Zinzaras E, Alexiou I et al. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in central Greece: a population survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:98 10.1186/1471-2474-11-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saraux A, Guedes C, Allain J et al. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis and spondyloarthropathy in Brittany, France. Societe de Rhumatologie de l'Ouest. J Rheumatol 1999;26:2622–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matos AA, Branco JC, Silva JC et al. Inquérito epidemiológico das doenças reumáticas numa amostra da população portuguesa (Resultados Preliminares). Acta Reumatol Port 1991;16:98. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Figeirinhas J. Estudo Epidemiológico dos reumatismos. Acta Reumatol Port 1976;IV:23.56. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Figeirinhas J. Alguns dados definitivos obtidos através do recente inquérito epidemiológico de reumatismos. Acta Reumatol Port 1976;IV:373–80. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Programa Nacional Contras as Doenças Reumáticas. s.l. Direção Geral de Saúde, 2004. www.dgs.pt/upload/membro.id/ficheiros/i006345.pdf

- 18.Ramiro S, Canhao H, Branco JC. EpiReumaPt Protocol—Portuguese epidemiologic study of the rheumatic diseases. Acta Reumatol Port 2010;35:384–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gouveia N, Rodrigues AM, Ramiro S et al. EpiReumaPt: how to perform a national population based study—a practical guide. Acta Reumatol Port 2015;40:128–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estatística INd. Relatório: Resultados definitivos dos CEnsus 2011, Portugal. Secondary Relatório: Resultados definitivos dos CEnsus 2011, Portugal, 2012.

- 21.Rodrigues AM, Gouveia N, da Costa LP et al. EpiReumaPt- the study of rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases in Portugal: a detailed view of the methodology. Acta Reumatol Port 2015;40:110–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Pereira LN et al. EQ-5D Portuguese population norms. Qual Life Res 2014;23:425–30. 10.1007/s11136-013-0488-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferreira LN, Ferreira PL, Pereira LN et al. The valuation of the EQ-5D in Portugal. Qual Life Res 2014;23:413–23. 10.1007/s11136-013-0448-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG et al. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1980;23:137–45. 10.1002/art.1780230202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pais-Ribeiro J, Silva I, Ferreira T et al. Validation study of a Portuguese version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Psychol Health Med 2007;12:225–35; quiz 35–7 10.1080/13548500500524088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039–49. 10.1002/art.1780290816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34:505–14. 10.1002/art.1780340502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hand. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:1601–10. 10.1002/art.1780331101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:600–10. 10.1002/acr.20140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum 1977;20:895–900. 10.1002/art.1780200320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aletaha D, Neogi T, Silman AJ et al. 2010 rheumatoid arthritis classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1580–8. 10.1136/ard.2010.138461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudwaleit M, Landewe R, van der Heijde D et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part I): classification of paper patients by expert opinion including uncertainty appraisal. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:770–6. 10.1136/ard.2009.108217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R et al. The development of Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society classification criteria for axial spondyloarthritis (part II): validation and final selection. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:777–83. 10.1136/ard.2009.108233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rudwaleit M, van der Heijde D, Landewe R et al. The Assessment of SpondyloArthritis International Society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:25–31. 10.1136/ard.2010.133645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bird HA, Esselinckx W, Dixon AS et al. An evaluation of criteria for polymyalgia rheumatica. Ann Rheum Dis 1979;38:434–9. 10.1136/ard.38.5.434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanis JA, Melton LJ III, Christiansen C et al. The diagnosis of osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 1994;9:1137–41. 10.1002/jbmr.5650090802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyphantis T, Kotsis K, Tsifetaki N et al. The relationship between depressive symptoms, illness perceptions and quality of life in ankylosing spondylitis in comparison to rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:635–44. 10.1007/s10067-012-2162-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoy D, March L, Brooks P et al. The global burden of low back pain: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:968–74. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1316–22. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cross M, Smith E, Hoy D et al. The global burden of hip and knee osteoarthritis: estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1323–30. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith E, Hoy DG, Cross M et al. The global burden of other musculoskeletal disorders: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1462–9. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanchez-Riera L, Carnahan E, Vos T et al. The global burden attributable to low bone mineral density. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1635–45. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith E, Hoy D, Cross M et al. The global burden of gout: estimates from the Global Burden of Disease 2010 study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:1470–6. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Annemans L, Spaepen E, Gaskin M et al. Gout in the UK and Germany: prevalence, comorbidities and management in general practice 2000–2005. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:960–6. 10.1136/ard.2007.076232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rodrigues SS, Caraher M, Trichopoulou A et al. Portuguese households’ diet quality (adherence to Mediterranean food pattern and compliance with WHO population dietary goals): trends, regional disparities and socioeconomic determinants. Eur J Clin Nutr 2008;62:1263–72. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reveille JD, Witter JP, Weisman MH. Prevalence of axial spondylarthritis in the United States: estimates from a cross-sectional survey. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:905–10. 10.1002/acr.21621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hukuda S, Minami M, Saito T et al. Spondyloarthropathies in Japan: nationwide questionnaire survey performed by the Japan Ankylosing Spondylitis Society. J Rheumatol 2001;28:554–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boyer GS, Templin DW, Cornoni-Huntley JC et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthropathies in Alaskan Eskimos. J Rheumatol 1994;21:2292–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Costantino F, Talpin A, Said-Nahal R et al. Prevalence of spondyloarthritis in reference to HLA-B27 in the French population: results of the GAZEL cohort. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:689–93. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Administração Central do Sistema de Saúde I. Actuais e Futuras Necessidades Previsionais de Médicos (SNS) 2011. https://saudeimpostos.files.wordpress.com/2011/.../actuais-e-futuras-necessidades

- 52.Poleshuck EL, Bair MJ, Kroenke K et al. Psychosocial stress and anxiety in musculoskeletal pain patients with and without depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2009;31:116–22. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Krishnan KR, France RD, Pelton S et al. Chronic pain and depression. II. Symptoms of anxiety in chronic low back pain patients and their relationship to subtypes of depression. Pain 1985;22:289–94. 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90029-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Oldendick RW, Bishop GF, Sorenson SB et al. A comparison of the Kish and last-birthday methods of respondent selection in telephone surveys. J Official Stat 1988;4:307–18. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gaziano C. Comparative analysis of within-household respondent selection techniques public opinion quarterly. 2005;69:124–57. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Palmer K, Walker-Bone K, Linaker C et al. The Southampton examination schedule for the diagnosis of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Ann Rheum Dis 2000;59:5–11. 10.1136/ard.59.1.5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]