Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is a leading cause of pneumonia and bronchiolitis in young children and the elderly. Therapeutic small molecules have been developed that bind the RSV F glycoprotein and inhibit membrane fusion, yet their binding sites and molecular mechanisms of action remain largely unknown. Here we show that these inhibitors bind to a three-fold-symmetric pocket within the central cavity of the metastable prefusion conformation of RSV F. Inhibitor binding stabilizes this conformation by tethering two regions that must undergo a structural rearrangement to facilitate membrane fusion. Inhibitor-escape mutations occur in residues that directly contact the inhibitors or are involved in the conformational rearrangements required to accommodate inhibitor binding. Resistant viruses do not propagate as well as wild-type RSV in vitro, indicating a fitness cost for inhibitor escape. Collectively, these findings provide new insight into class I viral fusion proteins and should facilitate development of optimal RSV fusion inhibitors.

RSV is a ubiquitous paramyxovirus that is the leading cause of acute lower respiratory tract infections in children less than 5 years of age1. In this age group, RSV is responsible for approximately 3 million hospitalizations each year. Disease severity is particularly high in the very young, with 6.7% of all deaths in children between 1 month and 1 year of age attributed to RSV2. In addition, RSV causes a substantial disease burden in the elderly, similar to that of non-pandemic influenza A3. Unfortunately, a safe and effective RSV vaccine is not yet available, although there are many candidates at various stages of development4. Currently, the only available intervention is passive prophylaxis with the humanized monoclonal antibody palivizumab (Synagis)5. However, the high cost of treatment and the requirement for monthly injections by medical practitioners restricts the use of this therapy to high-risk infants in developed countries6. Thus, there is an urgent need to develop alternative interventions that can be more easily provided to the entire cohort of at-risk children and elderly adults.

One strategy to reduce severe RSV disease is to block entry of the virus into cells lining the respiratory tract. The surface of RSV is coated with two glycoproteins: the attachment glycoprotein (G) and the fusion glycoprotein (F)7. Deletion of RSV G leads to a viable but attenuated virus, indicating that RSV G is not absolutely required for entry8. In contrast, RSV F is essential for entry, as it facilitates pH-independent fusion of the viral membrane with the host-cell plasma membrane, leading to infection of the host cell9. Expression of RSV F on the surface of cells can also cause fusion with neighboring cells, especially in vitro, leading to the formation of multinucleated syncytia. RSV F is a class I fusion glycoprotein that is synthesized as an inactive precursor (F0) that is processed by a furin-like protease at two sites to generate three polypeptides: the N-terminal fragment (F2), a 27-amino-acid glycopeptide (pep27) and the C-terminal fragment (F1). The mature, active protein exists as a trimer of F2–F1 heterodimers folded into a compact prefusion conformation10.

The process of membrane fusion begins once prefusion RSV F is triggered by an unknown mechanism to initiate a dramatic conformational change. This refolding can also occur spontaneously on virions and cell surfaces11, and it can be stimulated with heat12, indicating that prefusion RSV F is metastable. During the refolding, the hydrophobic fusion peptide at the N terminus of the F1 subunit pulls out from the central cavity of the prefusion trimer and inserts into the host-cell membrane7. The resulting pre-hairpin intermediate then further refolds as the heptad repeats adjacent to the fusion peptide (HRA) associate with the heptad repeats adjacent to the viral transmembrane region (HRB), located near the C terminus of the F1 subunit13. This association leads to the formation of an extremely stable six-helix bundle, which is characteristic of the RSV F postfusion conformation14,15, and brings the viral and host-cell membranes together. Inhibition of any of these steps during the fusion process may prevent entry and infection of the host cells and could thus serve as a target for therapeutic intervention.

Since the early 2000s, several low-molecular-weight organic compounds have been identified that inhibit virus-cell fusion and cell-cell syncytium formation in RSV-replication assays16–19. These small-molecule inhibitors of RSV fusion have neutralization efficacies in the low- to sub-nanomolar range, but their pharmaceutical development attrition rate has been high, and at present only one, GS-5806, has shown promise in recent early-phase clinical trials20,21. Previous investigations, including crystallographic studies22, suggested that these inhibitors bind to a late-stage fusion intermediate of RSV F and block zippering of the postfusion six-helix bundle23,24. However, the recent determination of the prefusion RSV F structure revealed that inhibitor-resistance mutations cluster around a central cavity within the trimer (Supplementary Results, Supplementary Fig. 1), suggesting a shared binding site in the prefusion conformation of F or a conserved, indirect mechanism of escape10,25.

To facilitate development of next-generation inhibitors, the aim of the current study was to elucidate the structural basis of small-molecule-mediated fusion inhibition for a diverse set of RSV inhibitors belonging to different chemotypes (Supplementary Fig. 2). We found that each inhibitor binds with high affinity to a three-fold-symmetric pocket within the central cavity of prefusion RSV F. We determined that the inhibitors are antagonists that stabilize the metastable prefusion conformation of RSV F by restricting the movement of two structurally labile regions. We also found that escape mutations occur in residues that directly contact the inhibitors or that are involved in the conformational flexibility required to accommodate inhibitor binding, and we demonstrated that viruses containing escape mutations do not propagate as well as wild-type RSV in vitro. Our data provide new insight into the small-molecule-mediated inhibition of viral fusion proteins and should facilitate the development of optimal RSV fusion inhibitors.

RESULTS

Inhibitors bind prefusion RSV F with high affinity

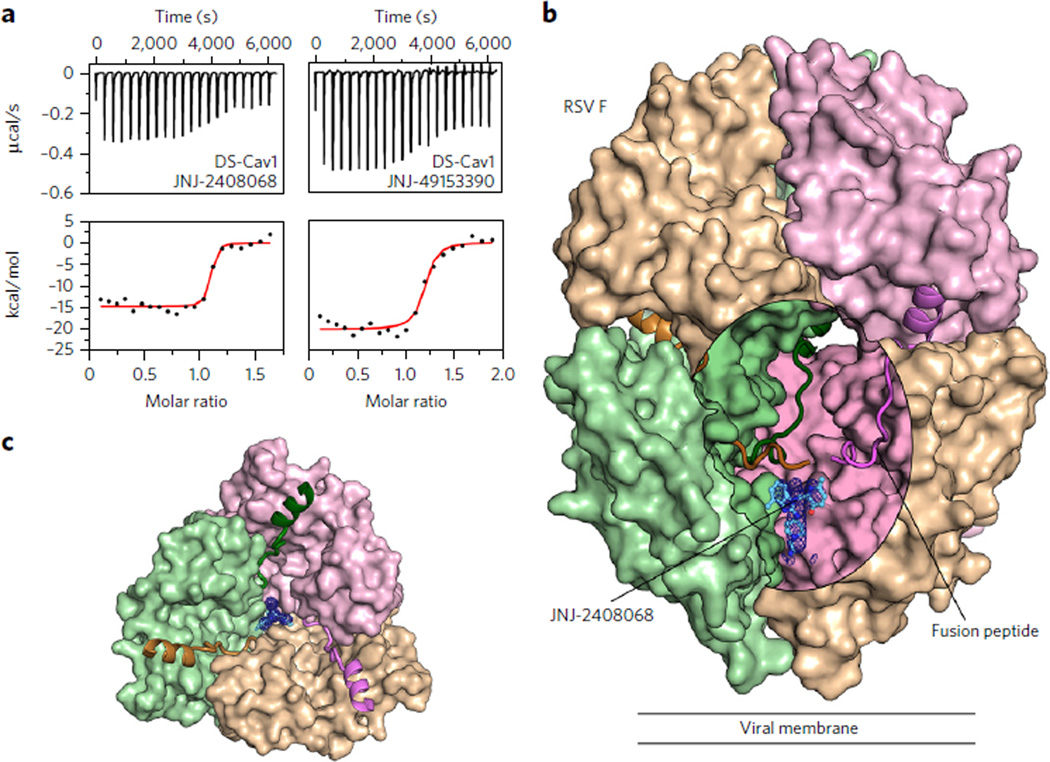

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) experiments were performed to assess the binding of inhibitors to a prefusion-stabilized RSV F variant, DS-Cav1 (ref. 10). Binding of the compounds to the prefusion conformation of RSV F was confirmed, and all tested inhibitors bound tightly, with equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) ranging from 1.7 to 39 nM (Fig. 1a, Table 1, and Supplementary Fig. 3a). Binding of the five compounds was enthalpically driven, with a stoichiometry of one inhibitor per trimer, suggesting that the binding site might be along the three-fold trimeric axis. As a control, JNJ-2408068, TMC-353121 and BMS-433771 were tested for binding to postfusion RSV F, and no binding was detected (Supplementary Fig. 3b). This is consistent with previous data that showed TMC-353121 is unable to bind to a preformed six-helix bundle22. To determine the correlation between inhibitor affinity and antiviral activity, neutralization studies were performed by infecting HeLa cells with an engineered RSV strain expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP) (rgRSV224)26. The four compounds with the highest affinities had EC50 values ranging from 0.10 to 6.8 nM, whereas BTA-9881, which had the lowest affinity, neutralized infection with an EC50 of 3,200 nM (Table 1). Collectively, these data reveal a positive correlation between inhibitor affinity and neutralization potency and thus support the hypothesis that the fusion inhibitors function by binding to the prefusion conformation of RSV F.

Figure 1. Inhibitors bind to a three-fold-symmetric cavity in prefusion RSV F.

(a) ITC data for the binding of JNJ-2408068 (left) and JNJ-49153390 (right) to prefusion RSV F (DS-Cav1). Red lines represent the best fit of titration data to a single-binding-site model. (b) Crystal structure of JNJ-2408068 bound to RSV F as viewed from the side. RSV F is shown as a molecular surface, except for the hydrophobic fusion peptides, which are shown as ribbons. An oval-shaped window into the central cavity has been created by removing a portion of the tan-colored protomer. Surfaces inside the cavity lack specular reflections. JNJ-2408068 is shown as a ball-and-stick representation with corresponding electron density shown as a blue mesh. (c) Top view of the structure shown in b, with the upper hemisphere of RSV F removed for clarity.

Table 1.

Tabulated ITC results for the binding of prefusion RSV F to five inhibitors

| Complex | Stoichiometrya | ΔH (kcal/mol) | −TΔS (kcal/mol) | Kd (nM) | EC50 (nM)b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JNJ-2408068 | 1.1 ± 0.00c | −15 ± 0.71 | 2.3 ± 1.0 | 1.7 ± 1.6 | 0.11 ± 0.06 |

| JNJ-49153390 | 1.1 ± 0.14 | −20 ± 0.0 | 8.9 ± 0.42 | 7.8 ± 7.4 | 0.16 ± 0.15 |

| TMC-353121 | 0.9 ± 0.014 | −16 ± 0.0 | 4.8 ± 1.3 | 8.7 ± 10 | 0.10 ± 0.10 |

| BTA-9881 | 1.1 ± 0.07 | −14 ± 3.5 | 3.3 ± 2.5 | 39 ± 28 | 3,200 ± 3,900 |

| BMS-433771 | 0.8 ± 0.21 | −18 ± 0.0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 11 ± 6.7 | 6.8 ± 6.1 |

Stoichiometry of fusion inhibitor to trimeric prefusion RSVF.

EC50 value for each inhibitor against a GFP-expressing RSV strain (rgRSV224).

Data represent the mean ± s.d. (n = 2).

Inhibitors tether structurally labile regions of RSV F

To elucidate the molecular basis of fusion inhibition, structures of each inhibitor bound to DS-Cav1 were determined, with resolutions ranging from 2.3 to 3.05 Å (Supplementary Table 1). Electron density for the compounds was readily observed within the central cavity of prefusion RSV F and was situated below the hydrophobic fusion peptides (Fig. 1b) and along the three-fold trimeric axis (Fig. 1c). This binding site, which is consistent with the stoichiometry of one inhibitor per trimer determined by ITC (Table 1), causes the electron density of each inhibitor to be observed as a three-fold average about the trimeric axis (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Depending on the three-dimensional (3D) structure of the compounds, there appear to be two modes of binding within the prefusion RSV F cavity. Inhibitors JNJ-2408068 (Fig. 2a), JNJ-49153390 (Fig. 2b) and BMS-433771 (Supplementary Fig. 5a) each occupy two of the three equivalent lobes of the binding pocket, whereas TMC-353121 (Supplementary Fig. 5b) and BTA-9881 (Supplementary Fig. 5c) are able to occupy all three lobes as a result of their pseudo-three-fold symmetry. For each of the inhibitors, the planar aromatic groups interact with the aromatic side chains of Phe140 and Phe488 located in the RSV F fusion peptide and the HRB, respectively. The fusion peptide, located at the N terminus of the F1 subunit, and the HRB, located at the C terminus of F1, both undergo dramatic conformational reorientations during the fusion process (Supplementary Fig. 1 and ref. 10). This suggests that the inhibitors act as antagonists of RSV F rearrangement by tethering the fusion peptide to HRB, thereby stabilizing the prefusion conformation. In addition to the aromatic-stacking interactions, inhibitors such as JNJ-2408068 and TMC-353121 have long, positively charged appendages that reach down into a negatively charged pocket formed by residues Asp486 and Glu487 (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 5b). That JNJ-2408068 and TMC-353121 were the two most potent compounds tested demonstrates the importance of these additional electrostatic interactions.

Figure 2. Inhibitors tether hydrophobic residues in two structurally labile regions.

(a,b) Top (left) and side views (middle) for JNJ-2408068 (a) and JNJ-49153390 (b) bound to RSV F. Each RSV F protomer is a different color (tan, pink and green), and hydrophobic side chains are shown with transparent molecular surfaces. Inhibitors are shown as ball-and-stick representations with carbon atoms colored in cyan, nitrogen atoms in blue, oxygen atoms in red, bromine atoms in dark red and sulfur atoms in yellow. At bottom are 2Dligand-interaction diagrams generated in Molecular Operating Environment; A, Band Crefer to the green, tan and pink protomers, respectively. Bonds with RSV F main chain and side chain atoms are shown as blue and green dashed lines, respectively, and an ionic interaction is shown as a purple dashed line. When present, arrowheads point toward the acceptor.

Mechanisms for inhibitor resistance

Comparison to the apo DS-Cav1 structure reveals that binding of the inhibitors traps or induces conformational changes in RSV F. The most prominent change is a displacement of Phe488 away from the three-fold axis, which increases the size of the binding pocket and allows Phe488 to form aromatic-stacking interactions with the inhibitors (Fig. 3a). To accommodate the repositioning of Phe488, the side chain of Phe137 in the fusion peptide rotates away from the three-fold axis. Additionally, the movement of Phe488 causes a bulge at Asp489, leading to the formation of hydrogen bonds with Thr400 from a neighboring protomer. Inhibitor binding thus requires a coordinated rearrangement of residues located within three discrete regions of the F1 amino acid sequence (Supplementary Video 1).

Figure 3. RSV F rearrangements required for inhibitor binding are prevented by the D489Yresistance mutation.

(a) Top view of RSV F apo (PDB ID 4MMS, green) superposed with the JNJ-2408068-bound (light purple) and D489Y (tan) RSV F crystal structures. The electron density of JNJ-2408068 in the bound structure is shown as a black mesh. The three RSV F protomers (labeled A, Band C) are separated by dashed gray lines emanating from the center of the three-fold axis. Salt bridges and interprotomeric hydrogen bonds between Lys394, Thr400 and Asp489 are shown as dotted lines in the lower left for the bound structure and to the right for the apo structure, and are absent in the D489Y structure at the top left. (b) Side view of the D489Y and JNJ-2408068-bound RSV F structures, colored as in a. Hydrogen bonds and salt bridges in the bound structure are shown as dotted lines. Hydrophobic side chains in the fusion peptide (Leu138, Phe140 and Leu141) and in the HRB (Tyr489) are shown with transparent molecular surfaces.

Mutations in any of these three regions may be expected to cause resistance to the fusion inhibitors. Indeed, all of these inhibitors select for escape mutations in the fusion peptide (F140I, L141W, G143S, V144A), in the cysteine-rich region (D392G, K394R, S398L, K399I, T400A/I) and in the HRB (D486N/E, E487D, F488I/V, D489Y) (Supplementary Table 2 and refs. 16,22,23,27). On the basis of the inhibitor-bound structures, there appear to be at least two mechanisms of escape that would decrease the affinity of the small molecules for RSV F. The first involves mutation of residues that directly contact the inhibitors. These include mutations F140I and F488I/V, which would eliminate the aromatic-stacking interactions with the inhibitors, and mutations D486N and E487D, which would reduce the electrostatic interactions with the positively charged inhibitors. The second mechanism involves mutations that do not directly contact the inhibitors but are predicted to prevent or disfavor the conformational changes required to accommodate inhibitor binding, such as mutations L141W, T400A/I and D489Y.

To investigate the structural basis for resistance, we expressed and purified DS-Cav1 containing the D489Y mutation, which allows escape from all of the inhibitors used in this study (Supplementary Table 2). ITC experiments demonstrated that JNJ-2408068 and BMS-433771 bound poorly to the DS-Cav1 D489Y variant, consistent with a direct escape mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 6). The D489Y variant crystallized in the same conditions as the apo and inhibitor-bound RSV F proteins, and its structure was determined to 2.6-Å resolution (Supplementary Table 1). In this structure, Tyr489 interacts with an umbrella of hydrophobic side chains from the fusion peptide—residues Leu138, Phe140 and Leu141. These hydrophobic interactions prevent movement of the D489Y main chain, locking Phe488 in the apo configuration and thus preventing binding of the fusion inhibitors (Fig. 3b). The interactions between the fusion peptide and Tyr489 would be predicted to tether the fusion peptide to the HRB and stabilize the prefusion conformation, which may offset the loss of the Asp489-Lys394 salt bridge and the Lys394-Thr400 hydrogen bond.

Antagonists of prefusion triggering

The binding mode of the small molecules suggested that they may stabilize the prefusion conformation and prevent triggering to the postfusion state. To test this hypothesis, we developed a cell-based triggering assay that uses a prefusion-specific antibody (CR9501) and a conformation-independent antibody (CR9503) to assess the conformation of RSV F28. Inhibitors were titrated into suspensions of HEK293 cells expressing wild-type RSV F on their surface, and these cells were then heat shocked at 55 °C for 10 min, which triggers the conversion of RSV F from the pre- to postfusion conformation12. In this assay, addition of the fusion inhibitors prevented triggering of RSV F in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4a). These results confirm that the fusion inhibitors interrogated in this study behave as antagonists that stabilize prefusion F and prevent its transition to the postfusion conformation.

Figure 4. Inhibitors stabilize prefusion RSV F.

(a) The relative percentage of surface-expressed RSV F remaining in the prefusion conformation after a 55 °C heat shock performed in the presence of increasing concentrations of fusion inhibitors. (b) Relative amount of prefusion RSV F on the surface of cells, normalized to wild type (Fwt), as assessed by the binding of the prefusion-specific antibody CR9501. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity of the Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated antibody. (c) Relative amount of total RSV F on the surface of cells, normalized to wild type, as assessed by the binding of the conformation-independent antibody CR9503. (d) Fraction of RSV F in the prefusion conformation on the surface of cells, as determined by the ratio of CR9501-binding to CR9503-binding. Many of the inhibitor-escape mutations (gray) reduce the fraction of RSV F in the prefusion conformation on the surface of HEK293 cells, although some mutations (blue) increase the fraction or maintain a similar level as wild type (black). For a, data represent the mean (n = 1–2). For b–d, data represent the mean ± s.d., where n = 7 for Fwt, n = 5 for D486N and D489Y, n = 4 for E487D, n = 3 for T400A and n = 2 for all other mutants.

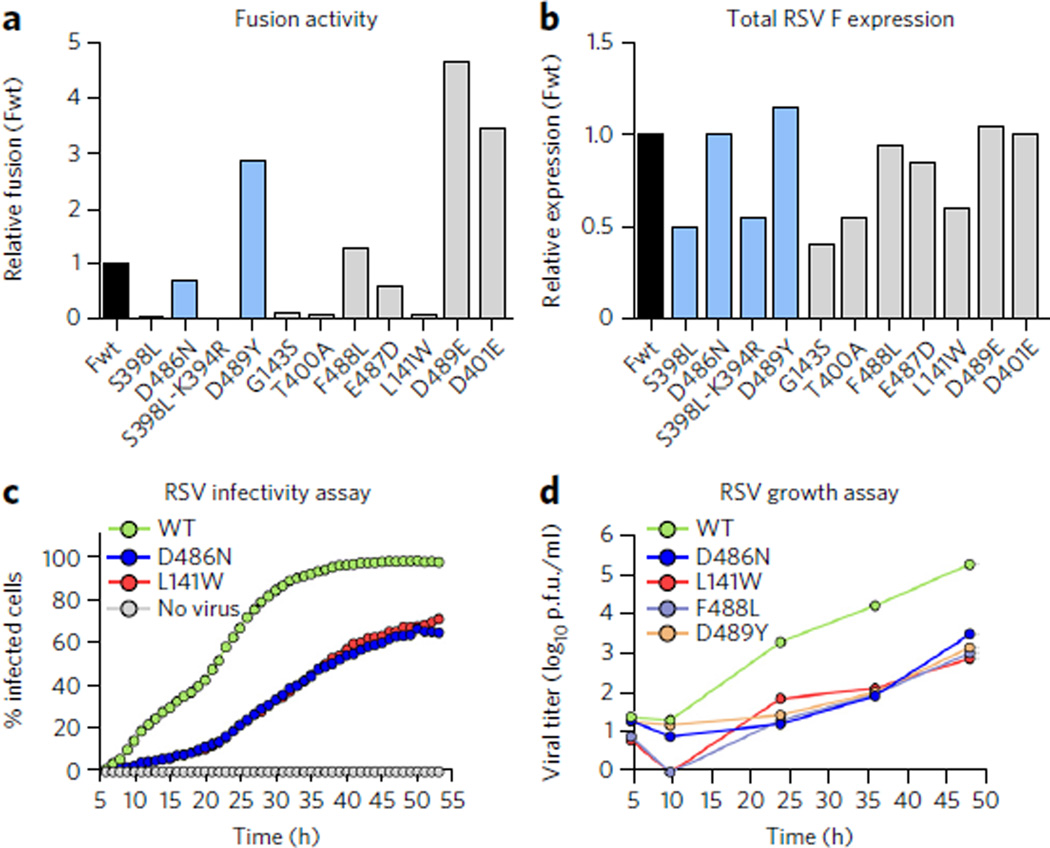

Escape mutations reduce viral fitness

It has previously been demonstrated that two inhibitor-escape mutations, D401E and D489E, result in hyperfusogenic F proteins, which may indirectly lead to escape by increasing the rate of fusion through destabilization of the prefusion conformation25. To determine whether all resistance mutations share these properties, we investigated the stability and fusogenicity of 11 RSV F variants containing documented inhibitor-escape mutations that were selected in vitro against different fusion inhibitors. The conformations of these variants on the surface of cells were assessed by flow cytometry using the antibodies CR9501 (Fig. 4b) and CR9503 (Fig. 4c). The previously reported destabilizing mutations D401E and D489E resulted in almost no prefusion F on the cell surface at 37 °C, confirming their destabilizing nature. The other nine variants, however, produced a range of stabilities, with some (S398L, D486N) increasing the stability of F and others (E487D, F488L) decreasing it (Fig. 4d).

We next sought to determine the effect of the escape mutations on RSV F–mediated cell-cell fusion. As previously observed25, expression of the D401E and D489E variants led to high levels of cell-cell fusion activity, approximately 3- to 4-fold above that of wild-type F (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, expression of the D489Y variant also resulted in high levels of cell-cell fusion activity even though this variant has a stability similar to that of the wild type. Other mutations, such as D486N, E487D and F488L, had fusion activity that was similar to or less than that of wild-type F. In general, there was not a strong correlation between stability and fusogenicity, which is not surprising given that cell-cell fusion activity should depend not only on RSV F stability but also on F expression levels as well as the function of each residue in the fusion process. To verify that all of the F proteins were expressed, cells transfected in parallel with those used for the fusion assay were stained with an affinity-matured version of palivizumab (motavizumab) and analyzed by ELISA (Fig. 5b). All of the F proteins were expressed, but five variants (S398L, S398L–K394R, G143S, T400A and L141W) had expression levels about 50% of wild type. Interestingly, for these five variants, little to no fusion activity was detected, suggesting that an expression threshold may need to be reached for cell-cell fusion to occur in this assay. Collectively, these data indicate that decreased stability and enhanced fusogenicity are not general properties of all inhibitor-escape variants.

Figure 5. Effects of inhibitor-escape mutations on cell-cell fusion activity and viral fitness.

(a) Relative fusion activity, normalized to wild-type F (Fwt), for RSV F variants containing inhibitor-escape mutations. Data represent the mean of two independent experiments, each replicated six times. (b) Relative RSV F surface expression, normalized to Fwt, as assessed by the binding of the conformation-independent antibody motavizumab to cells transfected in parallel with those used for the fusion assay. Data represent the mean of two independent experiments, each replicated three times. (c) The percentage of A549 cells infected with either wild-type (WT) rgRSV224 or inhibitor-escape variants (D486N or L141W) was measured by analyzing cellular GFP expression in individual cells every 60 min for 48 h starting 5 h after infection. Data represent the mean (n = 2). (d) The growth of WTRSV and inhibitor-escape variants was determined by a plaque titration assay in Vero cells. Data represent the mean of three replicates (n = 1 for each replicate).

For drug development, the effect of the escape mutations on viral fitness is more relevant than the effects on RSV F stability and activity. To determine the effect of the inhibitor-escape mutations on viral fitness, we quantified via time-lapse imaging the rate at which individual A549 cells became infected with either wild-type rgRSV224 or rgRSV224 strains with inhibitor-escape variants of F. We also determined the infectious virus titers in these A549 cell cultures by plaque assay over a period of two to three replication cycles, which was sufficient to infect all cells with wild-type rgRSV224. Throughout the 53-h time-course of the time-lapse imaging experiment, the wild-type virus infected a substantially greater fraction of cells than did viruses expressing inhibitor-escape variants D486N or L141W (Fig. 5c). The rate of infection for both mutant viruses was essentially the same, indicating that stabilizing and destabilizing mutations can produce similar reductions in viral infectivity in cell culture. In addition, the infectious titer produced by these A549 cells infected with wild-type rgRSV224 increased faster than the titers of the viruses with inhibitor-escape mutations (Fig. 5d), and after 48 h, the titer of the wild-type virus was almost 100-fold higher than the titers achieved by viruses containing inhibitor-escape mutations. Taken together, for those mutations tested here, the data indicate that escape from the potent fusion inhibitors leads to a reduction in viral fitness.

DISCUSSION

The structural and biophysical results presented in this work reveal that a diverse collection of small-molecule RSV fusion inhibitors bind to the prefusion conformation of RSV F. Each inhibitor binds to the same three-fold-symmetric site within the central cavity, interacting via aromatic stacking with phenylalanines in two labile regions required for membrane fusion. This mode of binding is expected to be conserved for all of the RSV fusion inhibitors under development, including Gilead’s GS-5806 compound, which has demonstrated efficacy in early-phase clinical trials21,29. On the basis of in silico docking experiments (Supplementary Fig. 7), GS-5806 is predicted to adopt a conformation similar to the BTA-9881 and TMC-353121 compounds, with GS-5806 occupying all three lobes of the binding pocket, interacting with Phe140 and Phe488 through aromatic stacking of its phenyl and pyrazolo[1,5-a]pyrimidine groups. The ability of this compound to occupy three lobes simultaneously may in part account for its high therapeutic efficacy.

In addition to the inhibitors’ mode of binding, results from our cell-based triggering assay provide strong evidence for a mechanism wherein the small molecules act as antagonists of membrane fusion by preventing triggering of the metastable prefusion conformation of RSV F. This mechanism is different than one previously proposed22,24, which suggested that these inhibitors bind to a pocket in the three-helix coiled-coil of a late prehairpin-intermediate structure of RSV F, thereby preventing full zippering of the postfusion six-helix bundle. In those investigations, photo-crosslinking experiments using RSV F–derived peptides corresponding to the HRA and HRB regions demonstrated that an analog of TMC-353121 could be crosslinked to Tyr198 in the HRA peptide, but only in the presence of HRB peptide. In addition, by mixing HRA and HRB peptides in the presence of TMC-353121, a crystal structure of the complex was obtained, which revealed that three TMC-353121 molecules each bound to a pocket in the HRA three-helix bundle and made interactions with Tyr198 as well as residues Asp486 and Glu487 in HRB. Although this structure explained the crosslinking results and the isolation of resistance mutant D486N in HRB, it did not explain resistance mutations in the cysteine-rich region (D392G, K394R, S398L, K399I, T400A/I) or in the fusion peptide (F140I, L141W, G143S, V144A). In contrast, our proposed mechanism—based on studies using biologically relevant prefusion and postfusion RSV F proteins—can account for the observed selection of resistance mutations in the fusion peptide and in the cysteine-rich region, as well as in the HRB. Although our proposed mechanism does not exclude the presence of the previously identified binding site in the HRA coiled coil, it does suggest that it is not relevant to the inhibitors’ mechanism of action in vivo. Furthermore, our proposed mechanism is consistent with that recently proposed for GS-5806 (ref. 30), suggesting that all RSV fusion inhibitors act as antagonists of F triggering.

From our inhibitor-bound structures of RSV F, we propose that there are at least two mechanisms of direct escape that would result in reduced affinity of the inhibitors for prefusion RSV F. These include an orthosteric mechanism, which involves mutation of amino acids that directly contact the inhibitors (for example, F488L), and an allosteric mechanism, in which amino acids distal from the binding site are mutated, preventing or disfavoring conformational changes required to accommodate inhibitor binding (for example, D489Y). A recent report characterized escape-variants D401E and D489E and demonstrated that these variants are hyperfusogenic in a cell-cell fusion assay and have reduced stability in thermal inactivation assays25. From these data, the authors proposed an indirect mechanism of escape, wherein the mutations destabilize RSV F and increase the rate of triggering, resulting in a smaller time window for the inhibitors to bind. Our results and proposed mechanisms of direct escape do not exclude an indirect mechanism of kinetic escape for those mutations that are destabilizing, nor are the two mechanisms mutually exclusive. A mutation such as D489E could both decrease the affinity for certain inhibitors and decrease the window of opportunity for inhibitor binding. Indeed, our flow cytometry assay demonstrates that the D401E and D489E variants are extremely destabilizing, resulting in little prefusion RSV F on the cell surface (Fig. 4b). However, we did observe that other mutations, such as S398L, D486N, and D489Y, either maintained or increased F stability (Fig. 4d). That the D489Y variant failed to bind inhibitors (Supplementary Fig. 6) provides additional evidence for a direct escape mechanism. Likely, there is not one universal mechanism of escape, and future work will be needed to characterize the escape mechanisms for each of the variants, which will be helpful in the design of next-generation inhibitors.

Results from our cell culture–based live-virus propagation assays (Fig. 5c,d) suggest that inhibitor-escape mutations in RSV F result in lower viral fitness in the RSV-Long and rgRSV224 strains. However, the pathogenicity of a D401E mutant in the RSV L19 strain was previously shown to be similar to that of wild-type L19 in a mouse model of RSV infection25. The differences in the outcomes of these studies may be explained in part by differences between the strains, as it has been demonstrated that L19 is inherently hyperfusogenic as the result of specific mutations in RSV F31. It is also possible that reduced infectivity and growth in cell culture do not directly correlate with pathogenicity in the mouse model of RSV disease. Further studies will be needed to investigate the relationship between RSV F stability, viral fitness and pathogenicity.

In addition to those for RSV, small-molecule fusion inhibitors against other class I viral fusion glycoproteins such as influenza hemagglutinin (HA) and HIV-1 Env have been previously described. The majority of these inhibitors block either receptor binding32–35 or the conformational changes required for fusion36–40. Of the latter group, the influenza fusion inhibitor umifenovir (Arbidol) may be most similar to the RSV compounds described here in that docking experiments suggest that Arbidol binds a cavity along the three-fold trimeric axis of influenza HA and interacts with the fusion peptide41. Interestingly, among class I fusion proteins for which structures are available, influenza HA has an interior fusion peptide arrangement most similar to RSV F (Supplementary Fig. 8). Thus, for RSV F, influenza HA and structurally related class I fusion proteins, cavities adjacent to the fusion peptide may represent promising targets for the development of small-molecule antivirals.

Future development of the RSV fusion inhibitors studied here will focus on improving both the potency and the pharmaceutical properties of the compounds. Although the crystal structures suggest that the aromatic groups are required to retain the essential binding mode, they also highlight regions that could support improvements in solubility, including a solvent-exposed region above the hydrophobic cavity and a negatively charged pocket below. That the binding site contains three equivalent lobes suggests that ideal fusion inhibitors should be three-fold symmetric. Although future studies will be needed to better understand the structure-activity relationship of these inhibitors and their mode of entry into the central cavity, our results should greatly facilitate the rational design of optimal inhibitors against this important childhood pathogen.

ONLINE METHODS

Compounds, viruses, and cells

TMC-353121, JNJ-2408068, and JNJ-49153390 were synthesized by the Medicinal Chemistry group at Janssen Infectious Diseases & Vaccines BVBA. Compounds BTA-9881 and BMS-433771 were synthesized and given as a generous gift from Biota Pharmaceuticals. All compounds were characterized and matched published or patented data. RSV Long strain was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Recombinant human rgRSV224 (ref. 26) was licensed from the National Institutes of Health. RSV viruses were grown in HeLa cells and stored in liquid nitrogen. HeLa cells were propagated in Eagle’s minimum essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 5% FBS (FBS), 2% sodium bicarbonate and 2 mM l-glutamine. Human embryonic kidney 293A cells obtained from the ATCC were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM), supplemented with 10% FBS, glutamine, penicillin, streptomycin and 10 mM HEPES, in a 37 °C humidified chamber with 5% CO2.

Production of RSV F proteins

Plasmids encoding RSV F prefusion (DS-Cav1) and postfusion (F ΔFP) proteins based on strain A2 (refs. 10,14) were transfected into FreeStyle 293F and Expi293 cells, respectively (Invitrogen). Proteins were expressed in the presence of kifunensine (5 µM) and were purified over Ni-NTA Superflow resin (Qiagen) and Strep-Tactin resin (IBA). For crystallization studies, purification tags were removed by overnight digestion with thrombin followed by gel filtration using a Superose 6 column (GE Healthcare Biosciences) with a running buffer of 2 mM Tris pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl. For ITC studies, tags were not removed and proteins were purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 column (GE) with a running buffer of PBS.

ITC experiments

Calorimetric titrations of inhibitors into DS-Cav1, the D489Y variant or postfusion RSV F were performed using a Nano ITC Standard Volume calorimeter (TA Instruments) at 25 °C. Prior to the experiments, proteins were dialyzed extensively at 4 °C into degassed PBS containing 1% DMSO, and inhibitors were diluted with the same buffer. Protein concentrations in the sample cell were 4.0–5.5 µM whereas the concentration of the inhibitors in the injection syringe was 37 µM. Titrations consisted of 10 µL injections, lasting 10 s and spaced 300 s apart. Data were processed with the NanoAnalyze 3.1 software (TA Instruments) and fit to an independent-binding model.

Crystallization and X-ray data collection

Crystals of D489Y in the DS-Cav1 background were produced by hanging-drop vapor-diffusion by mixing 1 µL of D489Y DS-Cav1 (4.4 mg/mL) with 0.5 µL of water and 0.5 µL of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 0.2 M lithium sulfate and 1.3 M potassium/sodium tartrate. Crystals of DS-Cav1–inhibitor complexes were also produced by the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method by mixing 1 or 2 µL of DS-Cav1 (5.9 mg/mL, 1% DMSO plus 125–250 µM inhibitors) with 1 µL of reservoir solution containing 0.1 M CHES pH 9.5, 0.2 M lithium sulfate and 1.4–1.6 M potassium/sodium tartrate. Crystals were transferred to a solution of 3.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M citrate pH 5.5, 1% DMSO plus 80–100 µM inhibitors, and were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. X-ray diffraction data for the DS-Cav1–BMS-433771 complex were collected to 2.85 Å at the SBC beamline 19-ID (Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory). All other X-ray diffraction data were collected to 2.3–3.05 Å at the ALS beamline 5.0.2 (Advanced Light Source, Berkeley Center for Structural Biology).

Structure determination, model building and refinement

Diffraction data were indexed and integrated in iMOSFLM42 and scaled and merged with AIMLESS43. Molecular replacement solutions for all data sets were obtained by PHASER44 using prefusion RSV F (PDB ID: 4MMS) as a search model. As with the apo structure of DS-Cav1 (ref. 10), each of the inhibitor-bound structures contained a single monomer in the P4132 asymmetric unit, with the three-fold trimeric axis aligned along the three-fold crystallographic axis. The structures were built manually in COOT45,46 and refined using PHENIX47. Ligands were placed into the electron density using the PHENIX.LigandFit GUI48 to a minimum correlation coefficient of 0.75 before refinement with PHENIX. The occupancy of the inhibitors was set to 0.33 due to their position on the three-fold crystallographic axis. Data collection and refinement statistics are presented in Supplementary Table 1.

Antiviral activity assays: inhibition of GFP expression

The antiviral activity of compounds against wild-type or mutant strains of rgRSV224, an engineered RSV virus that includes an additional green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene26, was determined by measuring inhibition of GFP expression. Black 384-well clear-bottom microtiter plates were filled with serial four-fold dilutions of compound in a final volume of 200 nL. Then, 30 µL of a HeLa cell suspension (1 × 105 cells/mL) in culture medium was added to each well followed by the addition of 10 µL rgRSV224 virus (multiplicity of infection [MOI] = 1) in culture medium using a multi-drop dispenser. Culture medium controls, virus controls, and mock-infected controls were included in each test. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Three days after virus exposure, viral replication was quantified by measuring GFP expression in the cells on a fully automated ARGUS laser microscope platform.

Antiviral activity assays: qRT-PCR

The antiviral activity of compounds against wild-type or mutants of RSV strain Long was measured by quantifying F protein RNA by qRT-PCR. To this end, 96-well microtiter plates were filled in duplicate with serial four-fold dilutions of compound in a final volume of 50 µL culture medium. Then, 100 µL of a HeLa cell suspension (5 × 104 cells/mL) in culture medium was added to each well followed by the addition of 50 µL RSV Long mutants in culture medium using a multi-drop dispenser. Cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Five days after virus exposure, 100 µL of supernatant from each well was collected, and the RNA was extracted using the DNA and Viral NA Small Volume Kit on a MagNA Pure 96 instrument (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Before the viruses were used in this assay, they were titrated by determining the linear range of the qRT-PCR assay on a four-fold dilution series of the particular stock.

In vitro resistance profiling

In vitro resistance selection was performed as described previously22. Briefly, RSV (Long and rgRSV224) was exposed to compounds at a starting concentration of 5 nM and grown in HeLa cells in the presence of compound until full cytopathic effect (CPE) was observed. At the end of each passage, extracellular virus from one or two end dilutions was harvested from culture supernatant, cleared of cellular debris, and used to initiate a subsequent passage at a five-fold higher compound concentration. Viruses were passaged in the presence of compound up to a concentration of 75 µM. In parallel, viruses were passaged in the absence of compound as a control. No mutations in the RSV F protein were detected when viruses were passaged in the absence of compound. The resulting isolates were cloned and the genes coding for F, G, and SH were amplified with RT-PCR. The amplicons were sequenced with a 3730 Xl DNA analyzer (Applied Biosystems). The extent of resistance was assessed using the antiviral assays described above.

Cell-surface triggering assays

Plasmids expressing wild-type or mutant RSV F were transiently transfected into HEK293T cells. Forty-eight hours post-transfection, cells were detached using an EDTA-containing buffer and immediately stained with Alexa Fluor 647–conjugated antibodies that were either specific for prefusion RSV F (antibody CR9501) or recognized both the pre- and postfusion conformations (antibody CR9503). Propidium iodide (Invitrogen) was used as a live-dead stain, and cells were analyzed by flow cytometry on a FACS Canto II instrument (BD Biosciences). The data were analyzed using FlowJo 9.6 software, and mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) were calculated. To assess the effect of the fusion inhibitors, a similar assay was performed except that the cells were heat-shocked at 55 °C for 10 min in the presence of increasing concentrations of fusion inhibitors before antibody staining.

Cell-cell fusion assay

Near confluent (85–90%) monolayers of 293A cells in 96-well Biocoat poly-d-lysine (Corning) dishes were transiently transfected with 0.1 µg of plasmid and Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Transfected 293A cells were incubated for 12 h at 37 °C in OptiMem containing 2% FBS, 1% glutamine and 10 mM HEPES. Cell-cell fusion was quantified by a luciferase expression system49. Parallel wells of transfected 293A cells were transfected with 0.1 µg of each RSV F plasmid and 0.1 µg of pFR-Luc (Agilent Technologies, La Jolla, CA), a reporter plasmid containing the Renilla luciferase gene driven by a minimal promotor and five Gal4 DNA binding sites. A second set of 293A cells were grown in 100 mm tissue-culture dishes and were transfected with 10 µg of pBD-NFκB, a plasmid expressing Gal4-NFκB (Agilent Technologies). At 12 h post-transfection, the target cells were released from the plate with Versene (Gibco), pelleted, resuspended in complete DMEM-10% FBS and 1.5 target cells/effector cell were added. At 20 h post-transfection, luciferase levels were quantified using the Steady-Glo Luciferase Assay System (Promega) and a Wallac 1420 VICTOR2 Luminometer (Perkin-Elmer) plate reader. Each construct was tested in sextuplicate. At 20 h post-transfection, parallel wells of RSV F-transfected 293A cells in 96-well plates were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, blocked with BSA diluent (Kirkegaard & Perry Laboratories, KPL), and stained with motavizumab at 12.5 ng/well for 1 h. Horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled goat anti-human antibody (KPL) and o-phenylenediamine dihydrochloride (OPD) substrate (ThermoFisher Scientific) were added and absorbance at 490 nm was quantified with the plate reader. Each construct was tested in triplicate.

Live virus propagation assay

The viral growth kinetics of wild-type and mutant rgRSV224 was measured by analyzing the cellular GFP expression in individual cells. Briefly, 2 × 103 A549 cells/well were seeded in black 384-well clear-bottom microtiter plates. One day after seeding, cells were infected by spin-inoculation with cooled wild-type or mutant rgRSV224 virus suspension at an MOI of 1 (infecting cells at 4 °C allows the virus to attach to cells but prevents virus from fusing with the host cells, synchronizing the infection). One hour after infection, cells were washed twice with cooled cell-culture medium. Then, cells were stained for one hour with 0.5 µL/well NucBlue Live and 0.1 µM CellTracker Orange. Cells were then washed once with cell-culture medium at 37 °C and placed at 37 °C in a Yokogawa CV7000 high-content reader equipped with a climate chamber and kept in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Live-cell images in 3 channels (NucBlue Live, CellTracker Orange and GFP) were captured every 60 min starting 5 h after infection. Two fields of view (2,498 × 2,098 pixels each) at 20× magnification were acquired in each well. Image analysis was performed using custom-written Acapella scripts executed in Columbus (PerkinElmer). First, nuclei were segmented based on NucBlue Live signal. Second, the cytoplasm of each cell was segmented based on CellTracker Orange signal using the nuclei as seeds. For each cell the mean GFP signal in the whole cell was computed and the single-cell data exported as text files. To calculate the percentage of infected cells per well, the single-cell measurements together with the original images and the segmentation masks of the cells and nuclei were imported to Phaedra50. After visual verification of the segmentation quality, a Knime workflow to classify each cell as infected or non-infected was executed. For each time point the workflow determined a threshold based on the distribution of the GFP signal of non-infected control cells and applied the threshold to all cells at the respective time point. The threshold was calculated as the mean + four s.d. of the GFP distribution after trimming off the 1st and 99th percentiles. Plausibility of the resulting classification was visually verified in Phaedra by displaying a class label for each cell on top of the original images.

Plaque titration assay

Vero cells grown in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, and 0.02 mg/mL gentamicin were seeded in 6-well plates until 80–100% confluence. Then, Vero cells were infected with 500 µL/sample (supernatant of infected cell culture, triplicates) as ten-fold dilutions (from 1:2 to 1:200,000) by a one hour incubation at room temperature under gentle rocking of the plates. Cell culture samples were aspirated subsequently and wells were washed once with PBS followed by addition of 3 mL/well of plaque-agarose medium (DMEM medium containing 5% FBS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 4% sodium bicarbonate and 120 U penicillin + 120 µg streptomycin/mL adjusted to pH 7.4 + 1.5% Seaplaque agarose) maintained at 40 °C. Plates were placed for 30 min at 4 °C and then incubated at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. After seven days, 2 mL of 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS was added to the wells and again incubated at room temperature for 2 h. Paraformaldehyde solution was then removed, the agarose overlay removed and then cells were stained with 200 µL/well of 0.4% methylene blue + 48% ethanol + 0.005% KOH in water. Finally, wells were rinsed with water, dried and plaques counted.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the McLellan lab and the Janssen Infectious Disease & Vaccines labs for comments on the manuscript, A. Draffan and C. Morton at Biota for BTA-9881 and BMS-433771, and E. Shipman for assistance with protein expression and purification. We thank P. Raboisson, S. Vendeville and J.-F. Bonfanti for design and assistance during synthesis of compounds, D. Wuyts for help in generating high-content imaging data, M. Van Ginderen and N. Verheyen for identification of mutant viruses, and I. Bisschop and R. Voorzaat for technical support. We thank C. Ralston, D. Bryant and members of the Berkeley Center for Structural Biology for help with X-ray diffraction data collection. The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported in part by the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Studies, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute. Results shown in this report were also derived from work performed at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center (SBC) at the Advanced Photon Source. We thank S. Ginell, J. Lazarz, M. Ficner-Radford and the beamline scientists for data collection support at SBC 19-ID. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the US Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research, under contract DE-AC02-06CH11357. This work was supported by the Janssen Infectious Diseases & Vaccines group, NIH grant AI 095684 (M.E.P.), and the Charles H. Hood Foundation, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts, USA (J.S.M.).

Footnotes

Accession codes. Coordinates and structure factors for RSV F in complex with fusion inhibitors JNJ-2408068, JNJ-49153390, TMC-353121, BTA-9881 and BMS-433771 have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession codes 5EA3, 5EA4, 5EA5, 5EA6 and 5EA7, respectively. Coordinates and structure factors for RSV F resistance mutant D489Y have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under accession code 5EA8.

Author contributions

M.B.B. crystallized inhibitor complexes, processed and refined X-ray data, and performed ITC experiments; P.F.-H. performed the triggering assay; S.C. and H.M.C. performed the cell-cell fusion assays; L.K. measured antiviral activity of compounds against wild-type and escape viruses; L.V. performed the time-lapse, high-content imaging of RSV-infected cell cultures; D.R., P.V. and S.J. designed the time-lapse, high-content imaging of RSV-infected cell cultures assay, developed software scripts for endpoint quantification and analyzed the data; T.H.M.J. contributed to the design, synthesis and selection of JNJ-49153390. D.R. and A.K. designed antiviral assays and assisted with data analysis; E.A. generated 2D ligand-interaction diagrams and docked GS-5806 into the JNJ-49155390-bound RSV F structure; J.P.L., M.E.P., D.R., and J.S.M. designed the study, analyzed data and, along with M.B.B., wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Competing financial interests

The authors declare competing financial interests: details accompany the online version of the paper.

Additional information

Any supplementary information, chemical compound information and source data are available in the online version of the paper. Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

References

- 1.Nair H, et al. Global burden of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60206-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lozano R, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380:2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Falsey AR, Hennessey PA, Formica MA, Cox C, Walsh EE. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in elderly and high-risk adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1749–1759. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson LJ, et al. Strategic priorities for respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine development. Vaccine. 2013;31(suppl. 2):B209–B215. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.11.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The IMpact-RSV Study Group. Palivizumab, a humanized respiratory syncytial virus monoclonal antibody, reduces hospitalization from respiratory syncytial virus infection in high-risk infants. Pediatrics. 1998;102:531–537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Smart KA, Lanctôt KL, Paes BA. The cost effectiveness of palivizumab: a systematic review of the evidence. J. Med. Econ. 2010;13:453–463. doi: 10.3111/13696998.2010.499749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McLellan JS, Ray WC, Peeples ME. Structure and function of respiratory syncytial virus surface glycoproteins. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;372:83–104. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karron RA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) SH and G proteins are not essential for viral replication in vitro: clinical evaluation and molecular characterization of a cold-passaged, attenuated RSV subgroup B mutant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:13961–13966. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.25.13961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walsh EE, Hruska J. Monoclonal antibodies to respiratory syncytial virus proteins: identification of the fusion protein. J. Virol. 1983;47:171–177. doi: 10.1128/jvi.47.1.171-177.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLellan JS, et al. Structure of RSV fusion glycoprotein trimer bound to a prefusion-specific neutralizing antibody. Science. 2013;340:1113–1117. doi: 10.1126/science.1234914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liljeroos L, Krzyzaniak MA, Helenius A, Butcher SJ. Architecture of respiratory syncytial virus revealed by electron cryotomography. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:11133–11138. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1309070110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yunus AS, et al. Elevated temperature triggers human respiratory syncytial virus F protein six-helix bundle formation. Virology. 2010;396:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.10.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lamb RA, Jardetzky TS. Structural basis of viral invasion: lessons from paramyxovirus F. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2007;17:427–436. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLellan JS, Yang Y, Graham BS, Kwong PD. Structure of respiratory syncytial virus fusion glycoprotein in the postfusion conformation reveals preservation of neutralizing epitopes. J. Virol. 2011;85:7788–7796. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00555-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao X, Singh M, Malashkevich VN, Kim PS. Structural characterization of the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein core. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:14172–14177. doi: 10.1073/pnas.260499197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cianci C, et al. Orally active fusion inhibitor of respiratory syncytial virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:413–422. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.2.413-422.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andries K, et al. Substituted benzimidazoles with nanomolar activity against respiratory syncytial virus. Antiviral Res. 2003;60:209–219. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Douglas JL, et al. Inhibition of respiratory syncytial virus fusion by the small molecule VP-14637 via specific interactions with F protein. J. Virol. 2003;77:5054–5064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.9.5054-5064.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bonfanti JF, et al. Selection of a respiratory syncytial virus fusion inhibitor clinical candidate. 2. Discovery of a morpholinopropylaminobenzimidazole derivative (TMC353121) J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:875–896. doi: 10.1021/jm701284j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roymans D, Koul A. In: Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. Resch B, editor. 2011. pp. 197–234. InTech. [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeVincenzo JP, et al. Oral GS-5806 activity in a respiratory syncytial virus challenge study. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:711–722. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1401184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roymans D, et al. Binding of a potent small-molecule inhibitor of six-helix bundle formation requires interactions with both heptad-repeats of the RSV fusion protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:308–313. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910108106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Douglas JL, et al. Small molecules VP-14637 and JNJ-2408068 inhibit respiratory syncytial virus fusion by similar mechanisms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2460–2466. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.6.2460-2466.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cianci C, et al. Targeting a binding pocket within the trimer-of-hairpins: small-molecule inhibition of viral fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15046–15051. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406696101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yan D, et al. Cross-resistance mechanism of respiratory syncytial virus against structurally diverse entry inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:E3441–E3449. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405198111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hallak LK, Collins PL, Knudson W, Peeples ME. Iduronic acid-containing glycosaminoglycans on target cells are required for efficient respiratory syncytial virus infection. Virology. 2000;271:264–275. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morton CJ, et al. Structural characterization of respiratory syncytial virus fusion inhibitor escape mutants: homology model of the F protein and a syncytium formation assay. Virology. 2003;311:275–288. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6822(03)00115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krarup A, et al. A highly stable prefusion RSV F vaccine derived from structural analysis of the fusion mechanism. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8143. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mackman RL, et al. Discovery of an oral respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion inhibitor (GS-5806) and clinical proof of concept in a human RSV challenge study. J. Med. Chem. 2015;58:1630–1643. doi: 10.1021/jm5017768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Samuel D, et al. GS-5806 inhibits pre- to post-fusion conformational changes of the RSV fusion protein. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015;59:7109–7112. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00761-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotard AL, et al. Identification of residues in the human respiratory syncytial virus fusion protein that modulate fusion activity and pathogenesis. J. Virol. 2015;89:512–522. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02472-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Madani N, et al. Small-molecule CD4 mimics interact with a highly conserved pocket on HIV-1 gp120. Structure. 2008;16:1689–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.LaLonde JM, et al. Structure-based design, synthesis, and characterization of dual hotspot small-molecule HIV-1 entry inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:4382–4396. doi: 10.1021/jm300265j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acharya P, et al. Structure-based identification and neutralization mechanism of tyrosine sulfate mimetics that inhibit HIV-1 entry. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011;6:1069–1077. doi: 10.1021/cb200068b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lin PF, et al. A small molecule HIV-1 inhibitor that targets the HIV-1 envelope and inhibits CD4 receptor binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:11013–11018. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832214100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Herschhorn A, et al. A broad HIV-1 inhibitor blocks envelope glycoprotein transitions critical for entry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2014;10:845–852. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Si Z, et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of HIV-1 entry block receptor-induced conformational changes in the viral envelope glycoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5036–5041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307953101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell RJ, et al. Structure of influenza hemagglutinin in complex with an inhibitor of membrane fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:17736–17741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807142105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Luo G, et al. Molecular mechanism underlying the action of a novel fusion inhibitor of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 1997;71:4062–4070. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.5.4062-4070.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bodian DL, et al. Inhibition of the fusion-inducing conformational change of influenza hemagglutinin by benzoquinones and hydroquinones. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2967–2978. doi: 10.1021/bi00063a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leneva IA, Russell RJ, Boriskin YS, Hay AJ. Characteristics of arbidol-resistant mutants of influenza virus: implications for the mechanism of anti-influenza action of arbidol. Antiviral Res. 2009;81:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCoy AJ, et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007;40:658–674. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adams PD, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terwilliger TC, Adams PD, Moriarty NW, Cohn JD. Ligand identification using electron-density map correlations. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2007;63:101–107. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906046233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Branigan PJ, et al. Use of a novel cell-based fusion reporter assay to explore the host range of human respiratory syncytial virus F protein. Virol. J. 2005;2:54. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornelissen F, Cik M, Gustin E. Phaedra, a protocol-driven system for analysis and validation of high-content imaging and flow cytometry. J. Biomol. Screen. 2012;17:496–506. doi: 10.1177/1087057111432885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.