Abstract

Background

In Germany, the annual mortality rate from cancer in the year 2011 was 269.9 deaths per 100 000 persons; every fourth death was due to cancer. A central objective of palliative care is to maintain the best possible quality of life for cancer patients right up to the end of their lives.

Methods

The PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases were systematically searched for pertinent publications, and the ones that were selected were assessed as recommended by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. As part of the German Guideline Program in Oncology, recommendations for the S3 Guideline on Palliative Care concerning seven different topics in the management of adult patients with incurable cancer were developed by a representative expert panel employing a consensus process.

Results

Opioids are the drugs of first choice for severe and moderately severe cancer-related pain, and for breathlessness. No clinically relevant respiratory depression was observed in any study. When opioids are used, accompanying medication to prevent constipation is recommended. Drugs other than opioids are ineffective against breathlessness, but clinical experience has shown that benzodiazepines and opioids can be used in combination in advanced stages of disease, or if the patient suffers from marked anxiety. Depression should be treated even in patients with a short life expectancy; psychotherapy is indicated, and antidepressant medication is indicated as well if depression is at least moderately severe. Communication skills, an essential component of palliative care, play a major role in conversations between the physician and the patient about the diagnosis, the prognosis, and the patient’s wish to hasten death. When the dying phase begins, tumor-specific treatments should be stopped.

Conclusion

Palliative care should be offered to cancer patients with incurable disease. Generalist and specialist palliative care constitute a central component of patient care, with the goal of achieving the best possible quality of life for the patient.

Every fourth man and every fifth woman in Germany dies of cancer (1). In view of this fact, the need for palliative care of those with incurable malignancies is high. Alongside comprehensive oncological management, integration of palliative medicine into the care of these patients plays a vital role in preservation of the best attainable quality of life right up to the time of death.

The quantity and quality of evidence in palliative medicine is constantly improving, with the result that to ensure universal first-class palliative care it has become necessary to formulate guidelines for everyday clinical care and the management of these patients. The guideline development group’s aim was to systematically gather and assess the scientific evidence relating to seven aspects of palliative medicine—breathlessness, cancer pain, constipation, depression, communication, dying phase, and palliative health care structures—and formulate recommendations based on the findings. In accordance with the principles of palliative medicine, the recommendations are intended to help maintain the best possible quality of life for cancer patients (eBox).

eBox. Recommendations on basic principles of palliative care.

Palliative care for patients with incurable cancer is centered around the quality of life of patients and their relatives (EC).

Palliative care is characterized by a multiprofessional and interdisciplinary approach (EC).

All persons involved in palliative care should be distinguished by an attitude which sees the patient as a human being with physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions, includes the patient’s relatives in the process, is truthful in dealing with those affected, and accepts dying and death as part of life (EC).

-

The following basic principles should be followed in the palliative care of patients with incurable cancer (EC):

Consider and respond to the patient’s needs in all four dimensions (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual)

Take account of patient preferences

Set realistic treatment goals

Be familiar with the organizational forms of palliative care

Create conditions that respect the patient’s privacy.

-

The following basic principles should be followed in the palliative symptom control of patients with incurable cancer (EC):

Carry out appropriate differential diagnostic investigation of the symptoms to permit specific treatment and identification of potentially reversible causes

Treat reversible causes whenever feasible and appropriate

Provide symptomatic treatment—alone or in parallel with causal treatment

Consider tumor-specific measures (e.g., radiotherapy, surgery, tumor drug treatment) with the sole or primary goal of symptom relief. A precondition is interdisciplinary cooperation between the various specialties and palliative medicine.

Discuss the benefits and burdens of these interventions honestly and openly with the patient, involving the relatives if appropriate.

-

The following basic principles should be followed in the palliative care of relatives of patients with incurable cancer (EC):

Consider and respond to the relatives’ needs and the burden they experience

Set realistic goals

Be familiar with specific support programs for relatives and provide information accordingly.

-

The following basic principles should be followed by those active in the palliative care of patients with incurable cancer (EC):

Be willing to evaluate and understand your potentials and limitations with regard to dying, death, and grieving and consciously reflect on your own mortality

Take advantage of your own and proffered potentials for salutogenesis and self-care

Be willing to obtain specialist qualifications

Persons with management functions should create a suitable environment.

Quality criteria for palliative care should include patient-reported outcomes (PRO) (EC).

(Source: German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer [2])

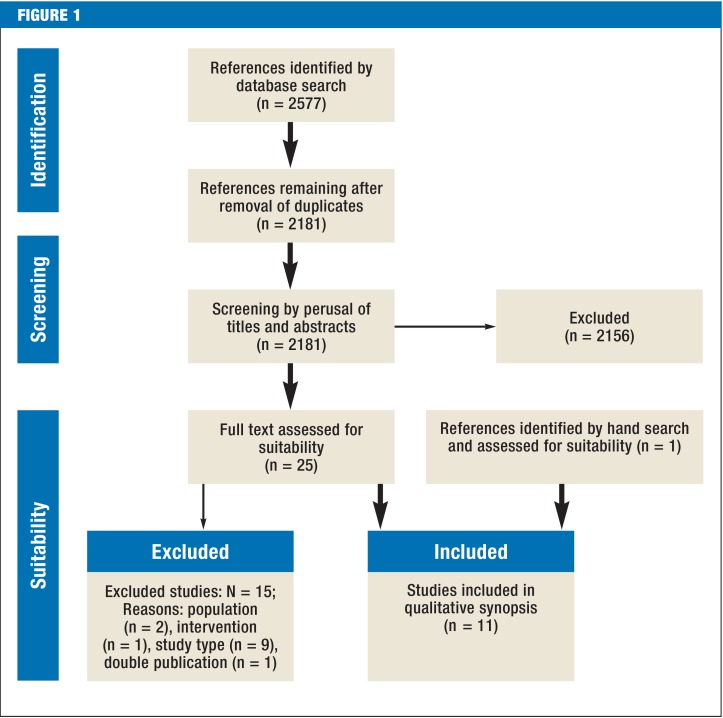

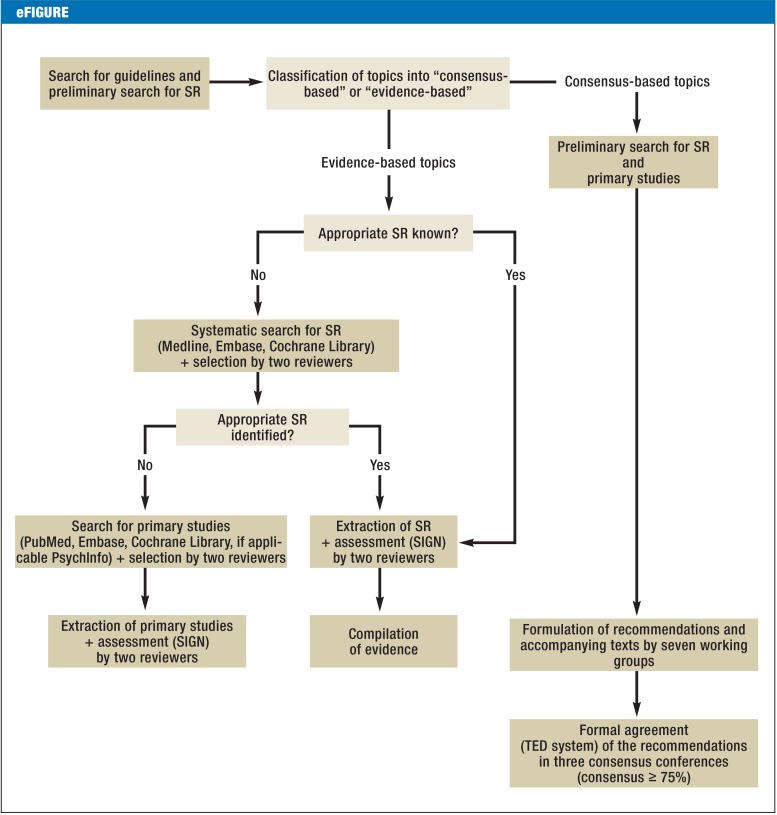

Methods

The German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer was developed under the leadership of the German Association for Palliative Medicine (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Palliativmedizin) within the methodological framework of the German Guideline Program in Oncology (2). The target group comprises all physicians and others involved in the treatment of patients with incurable cancer. Correspondingly, the representative consensus group consisted of elected representatives from 53 medical societies, patients’ organizations, and other institutions (eTable 1). Following agreement on 65 key questions, the group’s work began with a search for existing guidelines in the databases of three organizations: (G-I-N: Guidelines International Network; NGC: National Guideline Clearinghouse; AWMF: Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany). Next, systematic reviews and primary studies were sought in the databases PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library and by a hand search and selected according to the recommendations of the PRISMA Statement (Figure 1) (e1). On the basis of this body of evidence, seven working groups made up of elected representatives and other experts developed recommendations and explanatory texts (eFigure). Formal agreement on the recommendations was reached at three consensus conferences, where each recommendation was approved by at least 75% of those present.

eTable 1. Participating medical societies. organizations. professional associations. and experts.

| Participating medical societies and organizations | Elected representative | ||

| German Academy for Ethics in Medicine (AEM) | Dr. Alfred Simon. Linda Hüllbrock | ||

| Working Group on Education in the German Association of Palliative Medicine (AG AFW) | Axel Doll | ||

| Working Group of Dermatologic Oncology (ADO) | Dr. Katharina Kähler. Dr. Carmen Loquai | ||

| Working Group on Ethics in Palliative Care in the German Association for Palliative Medicine (AG Ethik) | Prof. Martin Weber | ||

| Working Group on Research in the German Association for Palliative Medicine (AG Forschung) | Prof. Christoph Ostgathe | ||

| German Standard Documentation of Palliative Care Working Group of the German Cancer Society (AG HOPE) | Prof. Lukas Radbruch | ||

| Oncology in Internal Medicine Working Group of the German Cancer Society (AIO) | Dr. Ulrich Wedding | ||

| Working Group on Palliative Care of the German Cancer Society (AG PM) | Dr. Bernd Alt-Epping. Prof. Florian Lordick. Dr. Joan Panke | ||

| Working Group Prevention and Integrative Oncology of the German Cancer Society (AG PriO) | Dr. Christoph Stoll | ||

| Working Group on Psychological Oncology of the German Cancer Society (AG PSO) | Dr. Pia Heußner. Dr. Monika Keller. Prof. Joachim Weis | ||

| Working Group on Urological Oncology of the German Cancer Society (AUO) | Dr. Chris Protzel | ||

| German Society of Hospital Pharmacists (ADKA) | Constanze Rémi. Dr. Stefan Amann | ||

| German Association for Psychosocial Oncology (dapo) | Dr. Thomas Schopperth | ||

| German Bishops’ Conference (DBK) | Ulrich Fink | ||

| German Society of Dermatology (DDG) | Dr. Carmen Loquai | ||

| German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV) | Prof. Pompiliu Piso. Prof. Stefan Fichtner-Feigl | ||

| German College of General Practitioners and Family Physicians (DEGAM) | Dr. Peter Engeser. Prof. Nils Schneider | ||

| German Society of Anaesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine (DGAI) | Prof. Christoph Müller-Busch | ||

| German Society for Care and Case Management (DGCC) | Dr. Rudolf Pape | ||

| German Society of Surgery (DGCH) | Prof. Stefan Mönig. Prof. Stefan Fichtner-Feigl | ||

| German Society of Skilled Nursing and Functional Services (DGF) | Elke Goldhammer | ||

| German Society of Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) | Dr. Martin H. Holtmann. Prof. Gerhard Werner Pott | ||

| German Society of Geriatrics (DGG) | Dr. Mathias Pfisterer | ||

| German Society of Gerontology and Geriatrics (DGGG) | Dr. Mathias Pfisterer | ||

| German Society of Geropsychiatry and Geropsychotherapy (DGGPP) | Dr. Klaus Maria Perrar | ||

| German Society of Gynecology and Obstetrics (DGGG) | Prof. Werner Meier. Prof. Christoph Thomssen | ||

| German Society of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. Head and Neck Surgery (HNO) | Prof. Barbara Wollenberg. Prof. Jens Büntzel | ||

| Deutsche Gesellschaft für Hämatologie und Medizinische Onkologie e. V. (DGHO) | Dr. Bernd-Oliver Maier. Dr. Werner Freier | ||

| German Society for Internal Medicine (DGIM) | Prof. Norbert Frickhofen | ||

| German Society for Internal Intensive Care Medicin and Emergency Medicine (DGIIN) | Prof. Uwe Janssens | ||

| German Society of Neurosurgery (DGNC) | Prof. Roland Goldbrunner | ||

| German Society of Neurology (DGN) | Prof. Raymond Voltz | ||

| German Association for Palliative Medicine (DGP) | Prof. Friedemann Nauck. Prof. Gerhild Becker | ||

| German Society of Nursing Science (DGP) | Dr. Margit Haas | ||

| German Respiratory Society (DGPB) | Prof. Helgo Magnussen | ||

| German Association for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (DGPPN) | Prof. Vjera Holthoff | ||

| German Society for Psychological Pain Therapy and Research (DGPSF) | Dipl.-Psych. Karin Kieseritzky | ||

| German Society for Radiation Oncology (DEGRO) | Dr. Birgit van Oorschot. Prof. Dirk Rades | ||

| German Society for Senology (DGS) | Prof. Ulrich Kleeberg | ||

| German Society of Urology (DGU) | Dr. Chris Protzel | ||

| German Interdisciplinary Association for Pain Management (DIVS) | Prof. Heinz Laubenthal (participation ended in September 2011) | ||

| German Pain Society | Prof. Winfried Meißner. Dr. Stefan Wirz | ||

| German Association for Social Work in Healthcare (DVSG) | Hans Nau. Franziska Hupke | ||

| Deutscher Bundesverband für Logopädie e. V. (DBL) | Ricki Nusser-Müller-Busch. Dr. Ruth Nobis-Bosch | ||

| German Hospice and Palliative Organization (DHPV) | Ursula Neumann | ||

| German Association of Occupational Therapists (DVE) | Carsten Schulze | ||

| German Association of Physical Therapy (ZVK) | Dr. Beate Kranz-Opgen-Rhein. Andrea Heinks | ||

| Evangelical Church in Germany (EKD)) | Prof. Traugott Roser | ||

| Women’s Self-Help After Cancer Organization (FSH) | Sabine Kirton | ||

| Working Group on Guidelines in the German Association for Palliative Medicine (LL DGP) | Prof. Claudia Bausewein | ||

| Conference for Oncologic Patient Care and Pediatric Patient Care (KOK) | Ulrike Ritterbusch. Kerstin Paradies | ||

| Sektion Pflege in der DGP e. V. (Sek Pflege) | Thomas Montag | ||

| Sektion weitere Professionen in der DGP e. V. (Sek Prof) | Dr. Martin Fegg | ||

| Women’s Health Coalition e. V. (WHC) | Irmgard Nass-Griegoleit | ||

| Additional participating experts | |||

| Dr. Elisabeth Albrecht | Dr. Thomas Jehser | Dr. Christian Scheurlen | |

| Dr. Susanne Ditz | Dr. Marianne Kloke | Dr. Jan Schildmann | |

| Prof. Michael Ewers | Dr. Tanja Krones | Dr. Steffen Simon | |

| Dr. Steffen Eychmüller | Norbert Krumm | Dr. Ulrike Stamer | |

| Prof. Thomas Frieling | Prof. Stefan Lorenzl | Prof. Michael Thomas | |

| Dr. Jan Gärtner | Heiner Melching | Dr. Martin Steins | |

| Manfred Gaspar | Dr. Elke Müller | Dr. Mariam Ujeyl | |

| Dr. Christiane Gog | Dr. Gabriele Müller-Mundt | Stefanie Volsek | |

| Jan Gramm | Dr. Wiebke Nehls | Dr. Andreas von Aretin | |

| Dr. Birgit Haberland | Prof. Günter Ollenschläger | Prof. Andreas von Leupoldt | |

| Dr. David Heigener | Dr. Susanne Riha | Prof. Maria Wasner | |

| Prof. Peter Herschbach | Dr. Roman Rolke | Prof. Jürgen Wolf | |

| Franziska Hupke | Dr. Susanne Roller | Dr. Heidi Wurst | |

| Dr. Jürgen in der Schmitten | Prof. Rainer Sabatowski | ||

| Stephanie Jeger | Dr. Christian Schulz | ||

Figure 1.

The PRISMA process, in this instance for studies on the effectiveness of opiods in the treatment of breathlessness (N = total, n = subtotal)

eFigure.

Procedure for the development of recommendations (adapted from the guideline report of the German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer, http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Palliativmedizin.80.0.html)

SR, systematic review(s); SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; TED, tele-dialog (voting system)

Results

The highest study quality was found for the areas breathlessness, pain, and depression. For the areas constipation, communication, and dying phase, the evidence was only moderate or weak. The quality of evidence with regard to palliative health care structures varied depending on structure, with the best results for specialist palliative home care. Overall, the guideline contains 13 statements and 217 recommendations, of which 100 are evidence based (recommendation strength and evidence level according to the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (Table 1) are given in parentheses in the following). The remaining 117 recommendations are based on expert consensus (EC). Furthermore, ten quality indicators were agreed.

Table 1. Grading of evidence (according to SIGN) and recommendations (according to AWMF standards).

| LoE | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1++ | High-quality meta-analyses. systematic reviews of RCTs. or RCTs with a very low risk of bias | ||

| 1+ | Well-conducted meta-analyses. systematic reviews of RCTs. or RCTs with a low risk of bias | ||

| 1– | Meta-analyses. systematic reviews. or RCTs with a high risk of bias | ||

| 2++ | High quality systematic reviews of case–control or cohort or studies High quality case–control or cohort studies with a very low risk of confounding or bias and a high probability that the relationship is causal | ||

| 2+ | Well-conducted case control or cohort studies with a low risk of confounding or bias and a moderate probability that the relationship is causal | ||

| 2– | Case–control or cohort studies with a high risk of confounding or bias and a significant risk that the relationship is not causal | ||

| 3 | Non-analytic studies. e.g.. case reports. case series | ||

| 4 | Expert opinion | ||

| Recommendation strength | Description | Implication for action | |

| A | Strong recommendation | Should | |

| B | Recommendation | Probably should | |

| 0 | Recommendation open | May | |

(Sources: www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign50.pdf and

SIGN. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; AWMF. Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany; LoE. level of evidence; RCT. randomized controlled trial

Breathlessness

Assessment

Breathlessness is “a subjective experience of breathing discomfort” (3) and should thus be assessed by the patient (EC). Management of breathlessness should, if possible and expedient, be preceded or accompanied by treatment of the cause (EC).

General treatment

General measures such as explanation, reassurance, relaxation exercises, and breathing exercises form an important part of the treatment of breathlessness (EC) (4). Two further non-pharmacological treatments showed moderate efficacy in a Cochrane review (5) and two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (6, 7): a stream of cool air on the face (e.g., from a hand-held fan; Borg mean value 2.6 [standard deviation (SD) 1.48] versus 3.7 [SD 1,83]; p = 0.003 [6]) and walking aids to increase mobility (B/1–).

Drug treatment

Oral or parenteral opioids should be used as drugs of choice for the relief of breathlessness (A/1+). The effectiveness of opioids has been clearly demonstrated (improvement of 9.5 mm on the visual analog scale [VAS], 95% confidence interval [3.0 mm; 16.1 mm]; p = 0.006) (8, 9). No instance of clinically relevant respiratory depression was observed in any of the studies (statement 1+). Particular care is required in the presence of severe renal insufficiency. If the adverse effects worsen, the choice and dose of opioid should be modified accordingly (B/3) (Table 2).

Table 2. Use of opioids depending on severity of renal insufficiency and advice on choice of opioid.

| Degree of renal insufficiency | Use of opioids | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mild to moderate renal insufficiency (GFR 30–89 mL/min) |

|

|||

| Severe renal insufficiency to complete renal failure (GFR <30 ml/min) |

|

|||

| Choice of opioid in the case of renal insufficiency | ||||

| Opioid | Active metabolites excreted exclusively via the kidneys | Removed by dialysis?*1 | Safe and effective in patients requiring dialysis?*2 | |

| Morphine | Yes | Yes | Avoid if possible | |

| Hydromorphone | (Yes) | Yes | Yes. with care | |

| Oxycodone | Yes | (Yes) | Unclear (limited evidence) | |

| Fentanyl | No | No | Yes. with care | |

| Buprenorphine | (Yes) | No | Yes. with care | |

*1Whether an opioid is removed by dialysis or not is a far more complex matter than implied by the simple yes/no classification. and it must also be taken into account whether metabolites are also removed by dialysis.

*2This advice on the use of opioids in patients requiring dialysis is a generalization and the optimal procedure may vary from patient to patient. Theefore. all opioids must be used with great care. The advice is based predominantly on case reports and clinical experience.

GFR. glomerular filtration rate

(Source: German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer [2]. adapted according to [e2–e4])

Other classes of drugs have shown no demonstrable effect. Nevertheless, an open recommendation was formulated for benzodiazepines owing to positive clinical experience of their use in combination with opioids, particularly in patients who have advanced disease or are in the dying phase (0/1–) and in the presence of severe anxiety. Phenothiazines, antidepressants, buspirone and glucocorticoids are not recommended (B/1–, for glucocorticoids B/1+).

There is high-quality evidence that oxygen is not effective for relief of breathlessness in non-hypoxemic patients (standardized mean difference = –0.09, 95% confidence interval [–0.22; 0.04]; p = 0.16) (10, 11). Oxygen therefore cannot be recommended for this group of patients (B/1+).

Cancer pain

The recommendations in this section are based on a modification of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) guideline on the use of opioids in the treatment of patients with cancer pain, which is based on an extensive review of the literature (12). An additional systematic literature search was carried out for the non-opioid analgesic metamizole (dipyrone), which is widely used in Germany.

Assessment

As for breathlessness, the severity of pain should if possible be assessed by the patient (EC).

Choice of drug

Step-II opioids or, alternatively, low-dose step-III opioids should be used to treat slight to moderate pain and whenever pain is not sufficiently controlled by non-opioid analgesics (B/1-).

The step-III opioids morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone can all be used as the drug of choice (0/1-), because three systematic reviews (13– 15) have shown that none of them is clearly superior to the others in efficacy or side effect profile. In the case of breakthrough pain, oral rapid-release opioids or transmucosal fentanyl should be administered (A/1+). As an alternative to oral opioids, fentanyl or buprenorphine can be given transdermally via delivery systems (0/1-), for instance if the patient suffers from dysphagia or simply prefers this form of drug delivery.

Amitriptyline, gabapentin, or pregabalin are recommended for the treatment of neuropathic cancer pain that cannot be sufficiently controlled with opioid analgesics (A/1+) (16).

The limited evidence for the efficacy of metamizole (17, 18), together with the clinical experience, justifies an open recommendation for the use of metamizole alone to treat slight pain or in combination with opioids for moderate to severe pain (0/1-).

Administration

Either slow-release or immediate-release oral preparations can be used for dose titration when opioid treatment is initiated (0/1-). Opioid switching can be considered if pain control is inadequate or severe adverse effects occur (0/3). Adverse effects may also be reduced by opioid dose reduction. In the case of renal insufficiency, the same precautions should be observed as described above for breathlessness (Table 2).

Constipation

Prophylaxis and treatment

Initiation of opioid treatment should be accompanied by medication to prevent constipation (EC).

Treatment of constipation should follow a stepwise approach (EC). First, osmotic (e.g., macrogol) or stimulating (e.g., bisacodyl, sodium picosulfate) laxatives should be given (A/1-) (19). If the symptoms are not successfully controlled, a combination of these two classes of laxatives should be tried. As a third step, peripheral opioid antagonists (e.g., methylnaltroxone, A/1+ [20]) are administered in addition to the step-2 laxatives in patients who require opioids for pain control. Step 4 involves the use of additional pharmacological (castor oil, erythromycin, amidotrizoate, etc.) or non-pharmacological (enemas, manual evacuation) measures. Any of these steps can be accompanied by physiotherapy treatments such as colonic massage.

Depression

The terms “depression” and “depressive episode” are used interchangeably in the following.

Screening and diagnosis

Because depressed patients often do not spontaneously talk about their mental state, the presence of depression should be actively and regularly assessed (A/4). A screening procedure should be used for this purpose (B/1+), e.g., a simple two-question instrument: “During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?” and “During the past month, have you often been bothered by little interest or pleasure in doing things?” (21). In the case of a positive response, i.e., if one of the two questions is affirmed, the existence of depression and, if present, its severity according to ICD-10 criteria should be ascertained (EC) and the risk of suicide assessed. The diagnosis of depression in the palliative care setting may not be easy, because the end of life is associated with a normal grieving process that can be very hard to differentiate from depression (eTable 2).

eTable 2. Characteristics of depression versus grieving reaction.

| Depression | Grieving reaction |

|---|---|

| Feeling of being cast out or alone | Feeling of connection to others |

| Feeling of unalterability | Feeling it will go away |

| Constant repetitive thoughts. hopelessness | Can enjoy memories |

| Pronounced loss of self-confidence | Retention of self-confidence |

| Constant | Fluctuating |

| No hope. no interest in the future | Forward looking |

| Little enjoyment of activities | Retains capacity for enjoyment |

| Suicidality | Wish to live |

Treatment

The appropriate treatment for depression depends on the severity of depressive symptoms (guideline recommendations adapted from the S3 Guideline/National Disease Management Guideline “Unipolar Depression” [22]). Psychotherapy should be offered even for mild depression, and certainly for moderate and severe depression (EC); behavioral or depth-psychology techniques should be used (EC). Pharmacological treatment should be offered to patients with moderate or severe depression (EC) and should follow the recommendations of the above-mentioned guideline (EC). The evidence from three systematic reviews confirmed the effectiveness of antidepressants versus placebo in the palliative setting (odds ratio [OR] 2.25, 95% confidence interval [1.38; 3.67]; p = 0.001), but showed no clear superiority of any one antidepressant over others (statement 1-) (23– 25). In the accompanying text, the guideline specifies three drugs that can be preferentially used in the palliative setting, based on both clinical and pharmacological criteria and the conclusions of a systematic review (23): mirtazapine, sertraline and citalopram.

Psychostimulants are ineffective in depression and should therefore not be used (B/1-).

Patients with a short prognosis

One aspect with particular relevance in the context of palliative medicine is the treatment of patients who have only a short time to live. Even if the life expectancy is just a few weeks, treatment should be initiated (EC). As the end of life approaches, more emphasis should be placed on short-term psychotherapeutic interventions.

Communication

Discussion of profound changes in the course of disease

Breaking bad news about the course of the cancer disease, including recurrence, is a challenging task and should primarily be handled by the treating physician (e.g., the patient’s primary care physician or oncologist) (EC). Information should be delivered piece by piece, not all at once, and the patient should be encouraged to ask questions (EC). If at all possible, the patient’s relatives should be involved in these conversations about the patient’s situation (EC).

Addressing dying and death

Even if they do not raise the subject unprompted, most patients welcome the opportunity to talk about end of life issues. All those directly involved with patient care should clearly convey their openness to such discussions, and words such as “dying” and “death” should be used in a sensitive way (EC).

If the patient expresses the wish to hasten death, this should be met with empathy and willingness to talk (EC). Such a statement does not automatically mean that the patient actually desires active shortening of life; it may conceal a cry for help and the wish to live (26, 27). Therefore, possible reasons for wanting to die must be discussed (EC).

Advance care planning

Advance care planning (eTable 3) offers patients in palliative care the opportunity to consider and stipulate in advance their preferences regarding the last phase of life. Patients should be given this chance in good time and repeatedly (EC).

eTable 3. Glossary.

| Term | Meaning in context of guideline |

|---|---|

| Relatives | Synonym: Family members |

| Palliative medicine | Synonyms: Palliative management. palliative care. palliative and hospice care. Aims to improve or maintain the quality of life of patients with an incurable disease and their relatives. Palliative medicine affirms life and sees dying as a natural process; it neither hastens nor postpones death. Palliative medicine and palliative care are used as synonyms in this guideline and both terms are understood in a broad sense. Palliative medicine is not reduced to the medicinal or medical component but interpreted broadly in the sense of multiprofessional palliative care. Despite the different ways in which palliative and hospice care have developed in Germany. they should be seen as a common approach or common attitude. Hospice care is rooted in civic involvement. Paid staff and volunteers work together in multiprofessional teams to offer a care package that aims to satisfy the needs and honor the wishes of each individual patient in a dignified. peaceful. and calm environment. |

| Generalist palliative care (GPC) | There is as yet no uniformly accepted definition of GPC. However. the new guideline presented here describes for the first time the tasks involved and defines the scope of GPC and SPC services within palliative medicine. Some of the characteristics of aspects of care that fit into the category of GPC are as follows:

|

| Specialist palliative care (SPC) | Some of the characteristics of aspects of care that fit into the category of SPC are as follows:

|

| Specialized outpatient palliative care (SOPV) | In the guideline. the written-out term “specialized outpatient palliative care” means services agreed by the guideline group and based on both clinical experience and evidence from studies that in some aspects (e.g.. definition of complexity) go beyond the definition of §§ 37b. 132d of the German Civil Code (GCC) V. In the context of the guideline. the abbreviation “SOPV” refers only to the care stipulated by law. |

| Dying phase | The last 3 to 7 days of life |

| Advance care planning | Synonyms: Comprehensive care planning. health care planning for the final phase of life according to § 132g GCC V-E; describes a systematic. interprofessionally accompanied communication and implementation process between the patient. the relatives. and the persons involved in the patient’s treatment. The aim is the best attainable accommodation of the individual preferences of the patient and his or her relatives with regard to treatment goal. treatment decisions. and priorities in the remaining period of life. e.g.. with regard to how and where the patient lives. where he or she dies. and the form taken by care. This goes beyond the concept of an advance care directive. |

(Source: German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer [2])

The dying phase

Identification

The guideline defines the dying phase as the last 3 to 7 days of life. The beginning of this phase can be determined using criteria such as breathing changes, alteration in state of consciousness and the emotions expressed (e.g., anxiety), increasing weakness and deterioration in general state, skin changes, confusion, and loss of interest in eating and drinking, together with the intuition of those involved in the patient’s care (0/4). These indicators were identified as a result of the findings of two systematic reviews and a Delphi survey (28– 30). The assessment should be made by an interprofessional team (B/4). There is currently no validated instrument for determining the beginning of the dying phase.

Frequent symptoms

Together with pain and breathlessness, another relatively frequent symptom in the dying phase is delirium. Treatment centers around general measures designed to comfort the patient. Should medication be needed, haloperidol is recommended (B/1-) (31). Death rattle is usually less disturbing for the patient than for the relatives and does not necessarily require treatment. Steps that can be taken if indicated include positioning techniques (0/4) and administration of anticholinergics (0/1-) (32). Tracheal secretions should not be sucked (B/4). Finally, if the patient becomes agitated in the days leading up to death the causes—e.g., pain, constipation, and delirium— should be established. Dying patients suffering from anxiety should be treated with general measures (EC). Benzodiazepines can be added (EC).

Medication and other measures

The decisive criterion for initiation or continuation of drug treatment in the days immediately before death is the goal of best attainable quality of life. With this aim in mind, the principal drug classes that can be used in the presence of treatable symptoms are opioids, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergics (EC). Tumor-specific treatments should be ended (EC). Equally, measures that will not help to achieve this goal should not be initiated; if already being used, they should be discontinued. This includes, for example, ventilation, dialysis/hemofiltration, intensive care, and repositioning to avoid bed sores or pneumonia (EC). If a defibrillator has been implanted, its cardioverter function should be deactivated (EC). Palliative sedation, administered by experienced and competent physicians and specialist nurses, is the last resort in the case of refractory distress (EC).

The guideline group recommends abstention from artificial nutrition and hydration of the dying patient (B/2), but the decision should be taken on an individual basis and after careful consideration (e.g., relief of hunger and thirst). This recommendation is based on six non-randomized trials (33, 34) and one RCT (35) on the effect of administration of fluids and was extrapolated, as indirect evidence, to parenteral feeding. The RCT showed no superiority of fluid administration over placebo in effect on selected symptoms of dehydration (-3.3 versus –2.8; p = 0.77).

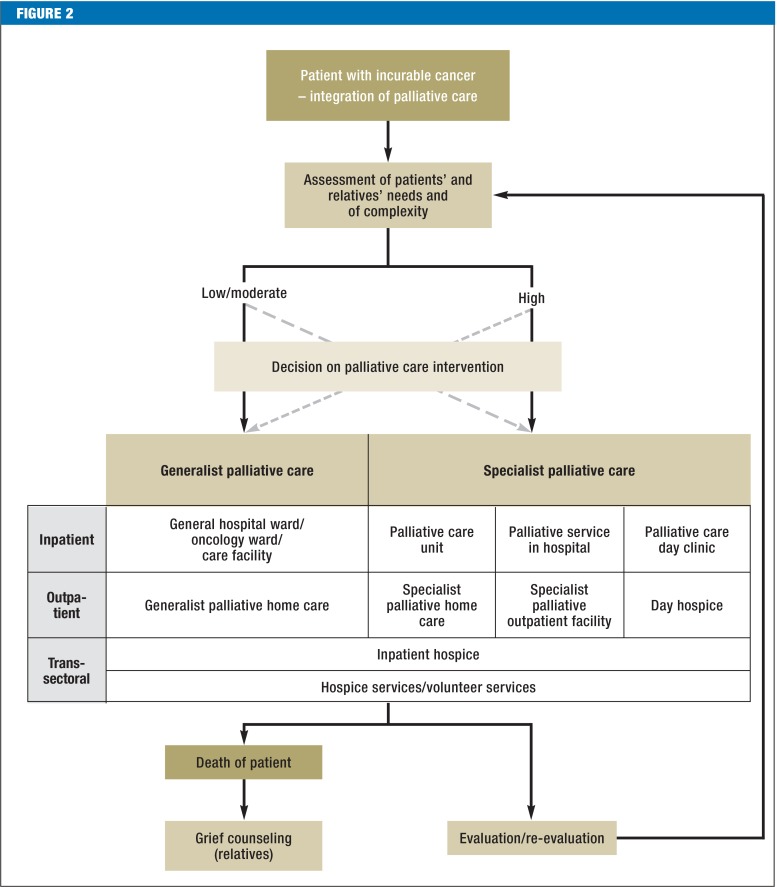

Palliative health care structures

Palliative care should be offered as soon as incurable cancer is diagnosed, although tumor-specific treatment can be given in parallel (EC). The palliative care structures available to patients in Germany with incurable cancer and their relatives as the disease progresses are depicted in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Treatment path for patients and relatives (source: German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer [2])

Whether generalist or specialist palliative care (eTable 3) is offered depends on the complexity of the patient’s situation. The following criteria are relevant for evaluation of complexity in the palliative setting (36): the needs of the patient and relatives—which have to be assessed in the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual dimensions (EC)—, the patient’s functional status, and the phase of disease (EC) (eTable 4). In the case of low to moderate complexity, generalist palliative care usually suffices. Specialist palliative care is indicated in highly complex situations (EC). This is the case, for instance, in the presence of pronounced physical symptoms that are difficult to control, in mentally unstable patients who are not coping with their disease, or in the lack of family support. The high complexity may be expressed in the constant need to adapt the treatment plan to changing circumstances.

eTable 4. Factors influencing the complexity of the patient’s situation and available instruments for assessment.

| Factor influencing complexity | Available instruments |

|---|---|

| 1. Patient’s problems and needs | E.g.. Minimal Documentation System (MIDOS 2). Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS/ revised version ESAS-r). Palliative Care Outcome Scale (POS). Distress Thermometer with problem list |

| 2. Strains on relatives | E.g.. Zarit Burden Interviews (ZBI). DEGAM Burden Scale for Family Caregivers (BSFC) |

| 3. Functional status | Functional status especially regarding activity. self-care. and self-determination. e.g.. Australian modified Karnofsky Performance Status (AKPS). Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG). activities of daily living (ADL). Barthel index |

| 4. Disease state: | Description |

| a) Stable | Symptoms relieved. patient’s needs satisfied by management plan. stable family situation |

| b) Unstable | Significant new problems or rapid worsening of significant old problems within a few days. amendment of treatment plan required urgently or less urgently in order to satisfy patient’s needs |

| c) Deteriorating | Symptoms worsening incrementally or continually over a period of weeks or development of new but anticipated problems over a period of days/weeks necessitating adjustment and regular review of management plan. with increasing strain on family and/or social/practical stresses |

| d) Dying (terminal) | Likelihood of death within next few days; necessity for regular—usually daily—review of management plan and provision of regular support for family |

(Source: German S3 Guideline on Palliative Care of Adult Patients With Incurable Cancer [2])

At the same time, the needs of the relatives must also be considered. Above all, they should be provided with information on support and counseling in grief and bereavement (EC).

General palliative measures can be administered by all those involved in the management of patients with cancer, provided they have basic qualification in palliative care (EC). Alongside recognizing the need for palliative measures and acting accordingly (EC), those concerned with palliative care should, for example, treat and manage symptoms and problems of low to moderate complexity, set treatment goals, and coordinate care, as well as taking steps to initiate specialist palliative care whenever indicated (EC).

A specialist palliative care team should include members from at least three occupational groups (physician, nurse, other occupation), of whom at least one physician and one nurse should possess a qualification in specialist palliative medicine (A/1-) (37– 40).

Conclusion

Although various factors make it difficult to conduct studies in palliative medicine, relatively good evidence could be identified, particularly with regard to the physical symptoms of cancer patients. With regard to palliative care structures, the findings of the numerous studies from other countries were not always applicable to the situation in Germany.

Key Messages.

Palliative care is multiprofessional and interdisciplinary and is centered around the quality of life of the patients and their relatives.

The evidence on the use of opioids for the treatment of breathlessness yields no indication of any clinically meaningful risk of respiratory depression.

The WHO step-III opioids morphine, oxycodone, and hydromorphone show similar efficacy and comparable side effect profiles.

Patients should be screened for depression on a regular basis, because depression at the end of life is often underdiagnosed but can be treated well.

The classes of drugs suitable for control of symptoms in the final days of life are opioids, antipsychotics, benzodiazepines and anticholinergics.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

The authors thank all elected representatives and experts for their energetic help in drawing up the guideline. Particular thanks are due to Dr. Markus Follmann, Prof. Ina Kopp, Dr. Monika Nothacker, Thomas Langer, and Dr. Simone Wesselmann of the German Guideline Program in Oncology for their advice on methods and their unwavering support. We are especially grateful to Verena Geffe of the guideline office. We are very thankful to the three bodies that created the German Guideline Program in Oncology and provided financial support: the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany, the German Cancer Society, and German Cancer Aid.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Bausewein has received author royalties for the book “Leitfaden Palliative Care” from Elsevier.

Dr. Simon has received study support (third-party funding) from Teva and Otsuka.

Prof. Nauck has received reimbursement of costs connected with lectures and seminars from Mundipharma, Archimedes, Roche, and Teva.

Prof. Voltz has received consultancy fees (advisory board) from the Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK; a large general statutory health insurance provider in Germany) and from Mundipharma, Teva, Archimedes, and Pfizer. He has received author royalties for the book “Leitfaden Palliative Care” from Elsevier. The Koblenz Social Court has paid him a honorarium for acting as an expert advisor. He has received reimbursement of conference attendance fees and travel costs as well as lecture honoraria from the AOK and from Mundipharma, Roche, MDS, Hexal, Archimedes, and MSA. He has been provided with study support by Teva.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.RKI, GEKID . Beiträge zur Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. Berlin: Robert Koch-Institut, Gesellschaft der epidemiologischen Krebsregister in Deutschland e. V.; 2013. Krebs in Deutschland 2009/2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leitlinienprogramm Onkologie (Deutsche Krebsgesellschaft - Deutsche Krebshilfe - AWMF) S3-Leitlinie Palliativmedizin für Patienten mit einer nicht-heilbaren Krebserkrankung. Langversion 1.1, 2015. AWMF-Registernummer: 128/001OL. http://leitlinienprogramm-onkologie.de/Palliativmedizin.80.0.html. (last accessed 5 November 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parshall MB, Schwartzstein RM, Adams L, et al. An official American Thoracic Society statement: update on the mechanisms, assessment, and management of dyspnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:435–452. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2042ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bausewein C, Simon ST. Shortness of breath and cough in patients in palliative care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:563–571. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0563. quiz 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Higginson I. Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005623.pub2. CD005623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bausewein C, Booth S, Gysels M, Kuhnbach R, Higginson IJ. Effectiveness of a hand-held fan for breathlessness: a randomised phase II trial. BMC Palliat Care. 2010;9 doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-9-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Galbraith S, Fagan P, Perkins P, Lynch A, Booth S. Does the use of a handheld fan improve chronic dyspnea? A randomized, controlled, crossover trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39:831–838. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abernethy AP, Currow DC, Frith P, Fazekas BS, McHugh A, Bui C. Randomised, double blind, placebo controlled crossover trial of sustained release morphine for the management of refractory dyspnoea. BMJ. 2003;327:523–526. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings AL, Davies AN, Higgins JP, Broadley K. Opioids for the palliation of breathlessness in terminal illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002066. CD002066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abernethy AP, McDonald CF, Frith PA, et al. Effect of palliative oxygen versus room air in relief of breathlessness in patients with refractory dyspnoea: a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2010;376:784–793. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uronis HE, Currow DC, McCrory DC, Samsa GP, Abernethy AP. Oxygen for relief of dyspnoea in mildly- or non-hypoxaemic patients with cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2008;98:294–299. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caraceni A, Hanks G, Kaasa S, et al. Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:e58–e68. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Caraceni A, Pigni A, Brunelli C. Is oral morphine still the first choice opioid for moderate to severe cancer pain? A systematic review within the European Palliative Care Research Collaborative guidelines project. Palliat Med. 2011;25:402–409. doi: 10.1177/0269216310392102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.King SJ, Reid C, Forbes K, Hanks G. A systematic review of oxycodone in the management of cancer pain. Palliat Med. 2011;25:454–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216311401948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pigni A, Brunelli C, Caraceni A. The role of hydromorphone in cancer pain treatment: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;25:471–477. doi: 10.1177/0269216310387962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bennett MI. Effectiveness of antiepileptic or antidepressant drugs when added to opioids for cancer pain: systematic review. Palliat Med. 2011;25:553–559. doi: 10.1177/0269216310378546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duarte Souza JF, Lajolo PP, Pinczowski H, del Giglio A. Adjunct dipyrone in association with oral morphine for cancer-related pain: the sooner the better. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15:1319–1323. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0327-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodriguez M, Barutell C, Rull M, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of oral dipyrone versus oral morphine for cancer pain. Eur J Cancer. 1994;30A:584–587. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(94)90524-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bader S, Weber M, Becker G. [Is the pharmacological treatment of constipation in palliative care evidence based?: a systematic literature review.] Schmerz. 2012;26:568–586. doi: 10.1007/s00482-012-1246-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Candy B, Jones L, Goodman ML, Drake R, Tookman A. Laxatives or methylnaltrexone for the management of constipation in palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003448.pub3. CD003448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell AJ, Meader N, Davies E, et al. Meta-analysis of screening and case finding tools for depression in cancer: evidence based recommendations for clinical practice on behalf of the Depression in Cancer Care consensus group. J Affect Disord. 2012;140:149–160. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde S3-Leitlinie/Nationale VersorgungsLeitlinie Unipolare Depression. www.awmforg/leitlinien/detail/ll/nvl-005html. Berlin, Düsseldorf: DGPPN, BÄK, KBV, AWMF, AkdÄ, BPtK, BApK, DAGSHG, DEGAM, DGPM, DGPs, DGRW; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rayner L, Price A, Evans A, Valsraj K, Higginson IJ, Hotopf M. Antidepressants for depression in physically ill people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007503.pub2. CD007503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rayner L, Price A, Evans A, Valsraj K, Hotopf M, Higginson IJ. Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in palliative care: systematic review and meta-analysis. Palliat Med. 2011;25:36–51. doi: 10.1177/0269216310380764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ujeyl M, Muller-Oerlinghausen B. [Antidepressants for treatment of depression in palliative patients ###: a systematic literature review] Schmerz. 2012;26:523–536. doi: 10.1007/s00482-012-1221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hudson PL, Schofield P, Kelly B, et al. Responding to desire to die statements from patients with advanced disease: recommendations for health professionals. Palliat Med. 2006;20:703–710. doi: 10.1177/0269216306071814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Voltz R, Galushko M, Walisko J, et al. Issues of “life” and “death” for patients receiving palliative care—comments when confronted with a research tool. Support Care Cancer. 2011;19:771–777. doi: 10.1007/s00520-010-0876-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Domeisen Benedetti F, Ostgathe C, Clark J, et al. International palliative care experts’ view on phenomena indicating the last hours and days of life. Support Care Cancer. 2012;6:1509–1517. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1677-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eychmüller S, Domeisen Benedetti F, Latten R, et al. “Diagnosing dying” in cancer patients - a systematic literature review. EJPC. 2013;20:292–296. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kennedy C, Brooks-Young P, Brunton Gray C, et al. Diagnosing dying: an integrative literature review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2014;4:263–270. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2013-000621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perrar KM, Golla H, Voltz R. Medikamentöse Behandlung des Delirs bei Palliativpatienten. Eine systematische Literaturübersicht. Schmerz. 2013;27:190–198. doi: 10.1007/s00482-013-1293-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wee B, Hillier R. Interventions for noisy breathing in patients near to death. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005177.pub2. CD005177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakajima N, Hata Y, Kusumuto K. A clinical study on the influence of hydration volume on the signs of terminally ill cancer patients with abdominal malignancies. J Palliat Med. 2013;16:185–189. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raijmakers NJH, van Zuylen L, Costantini M, et al. Artificial nutrition and hydration in the last week of life in cancer patients. A systematic literature review of practices and effects. Ann Oncol. 2011;22:1478–1486. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdq620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruera E, Hui D, Dalal S, et al. Parenteral hydration in patients with advanced cancer: a multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:111–118. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.6518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eagar K, Gordon R, Green J, Smith M. An Australian casemix classification for palliative care: lessons and policy implications of a national study. Palliat Med. 2004;18:227–233. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm876oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brumley R, Enguidanos S, Jamison P, et al. Increased satisfaction with care and lower costs: results of a randomized trial of in-home palliative care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:993–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, et al. Impact of an inpatient palliative care team: a randomized control trial. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:180–190. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jordhoy MS, Fayers P, Saltnes T, Ahlner-Elmqvist M, Jannert M, Kaasa S. A palliative-care intervention and death at home: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2000;356:888–893. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02678-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. NEJM. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e2.King S, Forbes K, Hanks GW, Ferro CJ, Chambers EJ. A systematic review of the use of opioid medication for those with moderate to severe cancer pain and renal impairment: a European Palliative Care Research Collaborative opioid guidelines project. Palliat Med. 2011;25:525–552. doi: 10.1177/0269216311406313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e3.Murtagh FE, Chai MO, Donohoe P, Edmonds PM, Higginson IJ. The use of opioid analgesia in end-stage renal disease patients managed without dialysis: recommendations for practice. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21:5–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e4.Twycross R, Wilcock A. 4 ed. Nottingham: Palliativedrugs.com Ltd; 2011. Palliative care formulary. [Google Scholar]

- e5.Block SD. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life: the art of the possible. JAMA. 2001;285:2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]