Abstract

There is a paucity of literature regarding microfracture surgery in the hip. The purpose of this study was to compare outcomes in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy predominantly for labral tears with focal full thickness chondral damage on the acetabulum or femoral head treated with microfracture and a matched control group that did not have focal full thickness chondral damage. A prospective matched-control study was performed examining four patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores: modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS), non-arthritic hip score, Hip Outcome Score—Activities of Daily Living (HOS-ADL), and Hip Outcome Score—Sports Specific Subscale (HOS-SSS) at minimum 2 years post-operatively between 35 patients undergoing microfracture for chondral defects during hip arthroscopy and 70 patients in a control group that did not have chondral defects. The patients were matched based on gender, age within 7 years, Workman’s compensation claim, labral treatment and acetabular crossover percentage less than or greater than 20. There was no significant difference (P > 0.05) in PRO scores preoperatively between the groups. Both groups demonstrated significant improvement (P < 0.05) in all post-operative PRO scores at all time points. There was no statistically significant difference (P > 0.05) in post-operative PRO scores between the microfracture and control groups, except for HOS-ADL and the visual analog scale (VAS) score, both of which were superior in the control group (P < 0.05). Patient satisfaction was 6.9 for the microfracture group and 7.7 for the control group (P > 0.05). Arthroscopic microfracture of the hip during treatment of labral tears results in favorable outcomes that are similar to the results arthroscopic treatment of labral tears in patients without full thickness chondral damage.

INTRODUCTION

Management of articular cartilage injuries is a challenge [1]. Defects in the articular cartilage have a limited capacity to heal regardless of the nature of injury [2]. Untreated lesions may lead to progression of arthritis and add to patient morbidity [3]. Chondral injuries in the hip can occur in a variety of hip disorders, can be atraumatic or traumatic, and can serve as an obscure source of pain. The goal of microfracture is to bring marrow cells and growth factors from the underlying bone marrow into the affected chondral defect. By penetrating the subchondral bone, pluripotent marrow cells can develop and form new fibrocartilage to fill the chondral defect. As the popularity of hip arthroscopy has increased in recent years, there has been a focus on prevention of chondral damage and managing pre-existing chondral injuries by extrapolating the technique and results of microfracture that has been validated in the knee [4].

Chondral injuries in the hip have been seen in association with multiple hip conditions including labral tears, loose bodies and dysplasia. McCarthy and Lee [5] noted a 59% prevalence rate of chondral injuries in the anterior acetabulum using arthroscopic evaluation. Furthermore, 70% of these lesions were grades III and IV using the Outerbridge classification system. The use of microfracture in treating chondral injuries of the hip has been documented in various case series [6–8]. However, studies with higher level of evidence and increased follow-up are needed to help understand the effects of this technique on hip preservation. The purpose of this study was to compare outcomes in patients undergoing hip arthroscopy predominantly for labral tears with full thickness chondral damage on the acetabulum or femoral head treated with microfracture and a matched control group that did not have full thickness chondral damage. The hypothesis of this study was that the patients undergoing microfracture would have similar outcomes to a matched control group of patients who did not have a microfracture.

METHODS

The study period was between September 2008 and December 2011. The patient-reported outcome (PRO) scores collected were the modified Harris Hip Score (mHHS), the Non-Arthritic Hip Score (NAHS) [9], the Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living (HOS-ADL) and the Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale (HOS-SSS) [10]. These were collected preoperatively, at 3 months and every successive year post-operatively for a minimum of 2 years. All four questionnaires are used, as it has been reported that there is no conclusive evidence for the use of a single PRO questionnaire for patients undergoing hip arthroscopy [11, 12]. Pain was estimated on a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) from 0 to 10 (10 being the worst). Satisfaction with surgery was measured with the question ‘How satisfied are you with your surgery results? (1 = not at all, 10 = the best it could be).’ Institutional review board approval was obtained for this study.

The inclusion criteria for this study were arthroscopic microfracture during surgery for labral tear and/or femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), with minimum 2-year follow-up. Exclusion criteria were revision surgeries, Tönnis grade 2 and higher, and previous hip conditions such as Legg-Calves-Perthes disease, avascular necrosis and prior surgical intervention. The matched pair control group was selected on a 1:2 ratio to patients who underwent hip arthroscopy for labral tear and/or FAI who did not undergo microfracture based on gender, age within 7 years, radiographic findings, Workman’s compensation claim, and labral treatment. The radiographs were analysed, and the patients were matched by acetabular crossover percentage <20 or >20. Patients with Tönnis grades 2 and above were excluded as they have been shown to have poorer outcomes with hip arthroscopy [13]. An acetabular crossover of 20% was used as a matching criterion since 20% has been shown to be a clinically relevant radiological sign of acetabular retroversion in symptomatic patients with FAI [14]. The matching criteria are shown in Table I. All patients who underwent microfracture had grade IV Outerbridge changes, which were focal in nature [15], to either the femoral head or acetabulum. All patients who did not undergo microfracture had grade III or less Outerbridge changes in either their femoral head or acetabulum. A wave sign, as described by Konan et al. [16] was not considered equivalent to Outerbridge grade IV and thus was not treated with microfracture.

Table I.

Matching criteria

| Gender |

| Age within 7 years |

| Crossover sign < 20% or ≥ 20% |

| Workman’s Compensation claim |

| Labral treatment |

Surgical technique

All hip arthroscopies were performed by the senior author (BGD). The indications for hip arthroscopy were predominantly labral tears with mechanical symptoms and failure of conservative treatment. The indications for revision hip arthroscopy included reinjury, instability, peritrochanteric pain, occult pain, heterotopic ossification and residual FAI [17]. All surgeries were performed in the modified supine position using a minimum of two portals (standard anterolateral and mid-anterior) [18–20]. Anterolateral and mid-anterior portals were established. A capsulotomy was performed with a beaver blade, incising the capsule parallel to the acetabular rim from 12 to 3 o’clock as described by Domb et al. [21] A diagnostic arthroscopy was performed.

Bony pathology was corrected under fluoroscopic guidance. An acetabuloplasty was performed for pincer impingement, and a femoral neck osteoplasty was performed for cam impingement. The cotyloid fossa was assessed for osteophytes and if present, a central acetabular decompression was performed as previously described by Gupta et al. [22] Labral tears were repaired when indicated or selectively debrided until a stable labrum was achieved while preserving as much labrum as possible. If there was full-thickness cartilage damage present, a microfracture was performed according to Steadman’s technique. The anterolateral and mid-anterior portals were predominantly used. Visualization was predominantly obtained from the anterolateral portal with the mid-anterior portal being used for instrument passage and performing the microfracture. For more superolateral lesions of the acetabulum, the portals were exchanged with the arthroscope placed in the mid-anterior portal visualizing laterally, while instruments were passed through the anterolateral portal to perform the microfracture. Using an arthroscopic shaver, loose flaps and portions of delaminated cartilage were removed. A ring curette was then used to create stable borders and to remove the calcified layer. Chondro picks by Arthrex with 220-mm shaft and 40°, 60° and 90° tips were used perpendicular to the subchondral bone and advanced with a mallet. Multiple holes were made 3–4 mm apart with a depth of 3–4 mm in the exposed subchondral bone plate adjacent to the healthy cartilage rim. The size and location of the lesion was noted using a 5-mm probe in mm2 and using the clock-face method, respectively [23, 24]. For purposes of statistical calculations, we added a value of 12 to anterior clock-face positions (clock-face values of 1–6 were represented as 13–8). Capsular closure was performed routinely as previously described by Domb et al. [21].

Rehabilitation protocol

In the control group, all patients were placed in a hip brace and instructed to be 20 pounds flat-foot weight-bearing on the operative extremity for the first 2 weeks post-operatively. Thereafter, weight-bearing status was gradually increased to full weight-bearing. Physical therapy began on the first post-operative day to initiate range of motion. This was accomplished by using a continuous passive motion machine for 4 h per day or using a stationary bike for 2 hours per day. The brace was discontinued 2 weeks post-operatively with emphasis on range of motion exercises. The same protocol was followed for microfracture patients; however, the period of wearing the hip brace and restricted weight bearing was carried out to 8 weeks.

Statistics

An a priori analysis was performed, and it was estimated a clinically significant difference between groups for mHHS would be 6.0 with a SD in each group being 8.0 [25]. To obtain a power of 0.80 or higher and a probability level of 0.05, with a ratio of 1:2, one would need a minimum of 30 hips in the microfracture group and 60 hips in the control group. A 2:1 ratio of control group to microfracture group was used to increase the robustness of the sample size. A two-tailed paired t-test was used to assess differences between pre and post-operative scores for the individual groups. The independent t-test was used to compare the mean change in PRO scores (change from pre to post-operative score) between the microfracture group and the matched-pair control group. A P values of < 0.05 was considered significant. The size and position of the microfractured lesions were correlated with PRO scores using linear regression analysis. Statistical analysis was done with Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, Washington, DC, USA) and IBM SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Patient population

Thirty-five patients that underwent a microfracture were available for minimum 2-year follow-up and average 3-year follow-up (range, 24–55 months) . The majority of the patients were male (63%). The average age was 42 years (range, 29–54 years) in the microfracture group and 42 (range, 24–61 years) in the control group. Thirty-two (91%) patients had acetabular microfracture and four (11%) had femoral microfracture. Six (17%) patients in the microfracture group were classified as workman’s compensation cases. Based on the matching criteria described in Table I, 70 patients were allocated to the control group. The microfracture and control groups showed no significant differences in demographic factors, namely, height, weight, BMI and age, or in other clinical factors including follow-up time and conversion to total hip replacement or hip resurfacing (HR) (Table II). All concomitant procedures performed for the microfracture and control groups are described in Table III. There were no significant differences in procedures performed between groups with the exception of acetabular and femoral chondroplasty (higher in the microfracture group), central acetabular decompression (higher in the microfracture group) and capsular repair (higher in the control group). Preoperatively, the mean PRO scores between the two groups were not significantly different, and are reported in Table IV.

Table II.

Demographic and clinical factors for microfracture and control groups

| Microfracture | Control | P values | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | 35 | 70 | |

| Gender (male) | 23 (65.71%) | 46 (65.71%) | 1 |

| Laterality (right) | 22 (62.86%) | 38 (54.29%) | 0.4 |

| Age at surgery (years) | 41.8 (28.5–53.9) | 42.1 (24.2–61.3) | 0.9 |

| Height (in) | 70 (63–78) | 68.3 (52–76) | 0.05 |

| Weight (lb) | 188.8 (120–266.5) | 176.8 (109–277) | 0.1 |

| BMI (kg/cm2) | 26.9 (19.6–38.8) | 26.4 (19.2–36) | 0.6 |

| Workers’ compensation claim | 6 (17.14%) | 12 (17.14%) | 1 |

| Follow-up time (months) | 32.7 (23.7–54.9) | 30.3 (23.8–67.9) | 0.2 |

| Conversion to THA/HR | 3 (8.57%) | 1 (1.43%) | 0.2 |

| Revision arthroscopy | 7 (20%) | 4 (5.71%) | 0.06 |

BMI, body mass index; THR, total hip replacement; HR, hip resurfacing.

Table III.

Prevalence of procedures performed during hip arthroscopy for microfracture and control groups

| Microfracture | Control | P values | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetabuloplasty | 20 (57.14%) | 52 (74.29%) | 0.07 | |

| Acetabular microfracture | 32 (91.43%) | 0 (0%) | <0.0001 | |

| Acetabular chondroplasty | 7 (20%) | 31 (44.29%) | 0.01 | |

| Acetabular subchondral cyst removal | 3 (8.57%) | 4 (5.71%) | 0.9 | |

| Capsular treatment | ||||

| Repair | 4 (11.43%) | 22 (31.43%) | 0.03 | 0.3 |

| Release | 29 (82.86%) | 48 (68.57%) | 0.1 | |

| Partial capsulotomy | 1 (2.86%) | 0 (0%) | 0.7 | |

| Central acetabular decompression | 4 (11.43%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02 | |

| Femoral osteoplasty | 29 (82.86%) | 59 (84.29%) | 0.9 | |

| Femoral head microfracture | 4 (11.43%) | 0 (0%) | 0.02 | |

| Femoral head chondroplasty | 2 (5.71%) | 16 (22.86%) | 0.03 | |

| Femoral subchondral cyst removal | 3 (8.57%) | 4 (5.71%) | 0.9 | |

| Gluteus medius/minimus repair | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.86%) | 0.8 | |

| Gluteus maximus transfer | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0.9 | |

| Iliopsoas release | 8 (22.86%) | 14 (20%) | 0.7 | |

| Iliotibial band release | 0 (0%) | 1 (1.43%) | 0.7 | |

| Labral treatment | ||||

| Repair | 18 (51.43%) | 36 (51.43%) | 1 | 1 |

| Debridement | 16 (45.71%) | 32 (45.71%) | 1 | |

| Reconstruction | 1 (2.86%) | 2 (2.86%) | 0.5 | |

| Ligamentum teres debridement | 23 (65.71%) | 38 (54.29%) | 0.3 | |

| Piriformis release | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.29%) | 0.5 | |

| Removal of loose body | 9 (25.71%) | 13 (18.57%) | 0.4 | |

| Sciatic neurolysis | 0 (0%) | 3 (4.29%) | 0.5 | |

| Trochanteric bursectomy | 2 (5.71%) | 9 (12.86%) | 0.4 |

Table IV.

Mean preoperative patient-reported outcome scores and VAS for microfracture and control groups

| Outcomes | Group | Mean | SD | P values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mHHS | Microfracture | 61.76 | 18.29 | 0.45 |

| Control | 59.17 | 15.32 | ||

| NAHS | Microfracture | 56.44 | 20.15 | 0.92 |

| Control | 56.06 | 18.72 | ||

| HOS-ADL | Microfracture | 63.01 | 20.03 | 0.74 |

| Control | 61.63 | 19.84 | ||

| HOS-SSS | Microfracture | 42.14 | 24.18 | 0.38 |

| Control | 37.59 | 25.13 | ||

| VAS | Microfracture | 5.94 | 2.40 | 0.79 |

| Control | 6.06 | 1.94 |

mHHS, Modified Harris Hip Score; NAHS, Non-Arthritic Hip Score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living; HOS-SSS, Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale; VAS, Visual Analog Score.

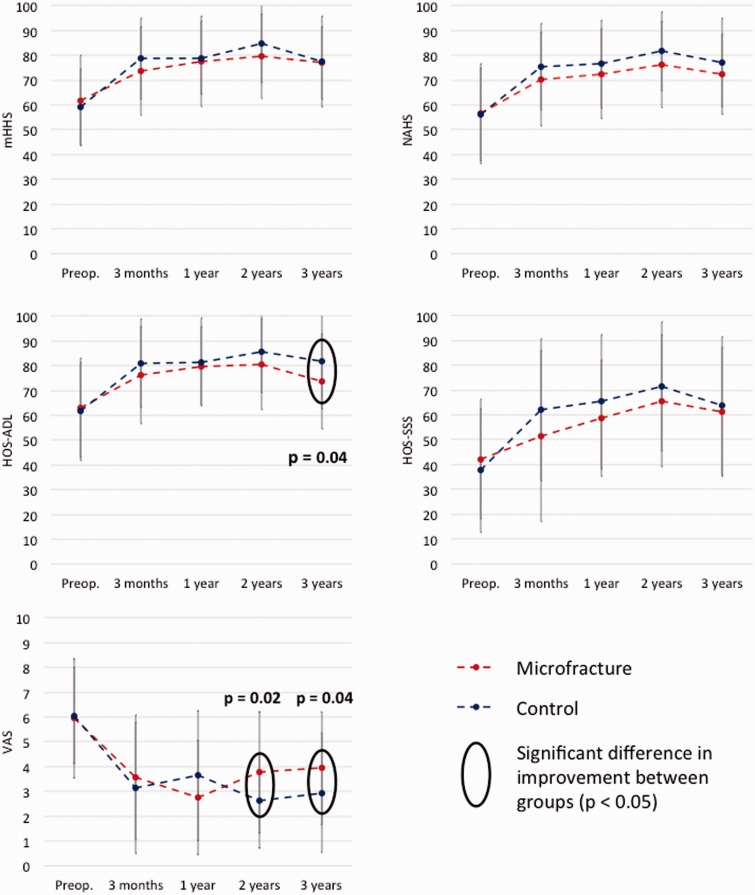

All improvements in PRO scores from preoperative to 3 years post-operatively were statistically significant (P < 0.01) for both groups (Fig. 1, Table V). Comparing the improvements in PRO scores between the microfracture and control groups, there were no statistical differences at any time point in mHHS, NAHS and HOS-SSS scores. The 3-year HOS-ADL and the 2- and 3-year VAS scores were significantly better (P < 0.05) in the control group compared with the microfracture group (Fig. 1). Post-operative patient satisfaction at 3 years post-operatively was 6.91 for the microfracture group and 7.73 for the control group, which was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) (Table VI). Figure 1 shows the mean PRO scores for both groups at all the time points.

Fig. 1.

Mean PRO scores for microfracture and control groups at preoperative, 3 month, 1-, 2- and 3-year time points. mHHS, Modified Harris Hip Score; NAHS, Non-Arthritic Hip Score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living; HOS-SSS, Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale; VAS, Visual Analog Score.

Table V.

Mean preoperative PRO scores and VAS for microfracture and control groups

| Outcomes | Status | Microfracture |

Control |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | P values | Mean | SD | P values | ||

| mHHS | Preoperative | 61.76 | 18.29 | <0.001 | 59.17 | 15.32 | <0.001 |

| 3 years post-operative | 77.02 | 14.78 | 77.62 | 18.45 | |||

| NAHS | Preoperative | 56.44 | 20.15 | <0.001 | 56.06 | 18.72 | <0.001 |

| 3 years post-operative | 72.32 | 16.14 | 77.18 | 18.02 | |||

| HOS-ADL | Preoperative | 63.01 | 20.03 | 0.005 | 61.63 | 19.84 | <0.001 |

| 3 years post-operative | 73.58 | 19.14 | 81.97 | 19.47 | |||

| HOS-SSS | Preoperative | 42.14 | 24.18 | <0.001 | 37.59 | 25.13 | < 0.001 |

| 3 years post-operative | 61.14 | 26.09 | 63.65 | 27.92 | |||

| VAS | Preoperative | 5.94 | 2.40 | <0.001 | 6.06 | 1.94 | < 0.001 |

| 3 years post-operative | 3.94 | 2.29 | 2.94 | 2.41 | |||

mHHS, Modified Harris Hip Score; NAHS, Non-Arthritic Hip Score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living; HOS-SSS, Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale; VAS, Visual Analog Score.

Table VI.

Mean pre and post-operative PRO scores in the microfracture and control groups at various time points

| Outcomes | Group | 3 months | 1 year | 2 years | 3 years | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | P values | Mean | SD | P values | Mean | SD | P values | Mean | SD | P values | ||

| mHHS | Microfracture | 73.81 | 17.95 | 0.22 | 77.72 | 18.37 | 0.79 | 79.73 | 17.11 | 0.19 | 77.02 | 14.78 | 0.87 |

| Control | 78.74 | 16.42 | 78.98 | 14.88 | 84.61 | 15.79 | 77.62 | 18.45 | |||||

| Δ Microfracture | 12.71 | 20.24 | 0.30 | 19.19 | 20.64 | 0.92 | 17.34 | 16.02 | 0.048 | 15.35 | 16.05 | 0.48 | |

| Δ Control | 17.34 | 17.51 | 19.72 | 14.59 | 25.09 | 17.73 | 18.23 | 20.62 | |||||

| NAHS | Microfracture | 70.40 | 18.91 | 0.24 | 72.51 | 18.03 | 0.43 | 76.42 | 17.49 | 0.16 | 72.32 | 16.14 | 0.18 |

| Control | 75.37 | 17.33 | 76.50 | 17.79 | 81.66 | 15.96 | 77.18 | 18.02 | |||||

| Δ Microfracture | 15.98 | 20.43 | 0.81 | 16.94 | 17.49 | 0.57 | 20.11 | 18.64 | 0.40 | 15.89 | 15.65 | 0.17 | |

| Δ Control | 17.02 | 17.33 | 19.44 | 14.08 | 23.57 | 17.78 | 21.10 | 19.35 | |||||

| HOS-ADL | Microfracture | 76.24 | 19.81 | 0.29 | 79.86 | 15.87 | 0.72 | 80.55 | 18.29 | 0.20 | 73.58 | 19.14 | 0.04 |

| Control | 80.95 | 17.88 | 81.56 | 17.90 | 85.46 | 16.32 | 81.97 | 19.47 | |||||

| Δ Microfracture | 15.04 | 20.14 | 0.44 | 19.98 | 15.24 | 0.74 | 17.21 | 20.82 | 0.20 | 10.57 | 20.83 | 0.02 | |

| Δ Control | 18.42 | 17.51 | 21.48 | 16.66 | 22.76 | 18.51 | 20.52 | 20.21 | |||||

| HOS-SSS | Microfracture | 51.50 | 34.52 | 0.16 | 58.58 | 23.43 | 0.36 | 65.70 | 26.80 | 0.33 | 61.14 | 26.09 | 0.66 |

| Control | 62.09 | 28.69 | 65.37 | 27.14 | 71.52 | 26.24 | 63.65 | 27.92 | |||||

| Δ Microfracture | 10.21 | 38.91 | 0.20 | 20.99 | 25.65 | 0.13 | 24.02 | 27.36 | 0.24 | 19.00 | 29.50 | 0.34 | |

| Δ Control | 20.16 | 27.40 | 32.19 | 25.71 | 31.86 | 30.31 | 25.50 | 34.11 | |||||

| VAS | Microfracture | 3.57 | 2.54 | 0.52 | 2.75 | 2.31 | 0.23 | 3.77 | 2.45 | 0.02 | 3.94 | 2.29 | 0.04 |

| Control | 3.13 | 2.65 | 3.63 | 2.62 | 2.62 | 1.91 | 2.94 | 2.41 | |||||

| Δ Microfracture | −2.35 | 2.39 | 0.70 | −3.65 | 2.43 | 0.13 | −1.97 | 2.83 | 0.01 | −2.00 | 2.47 | 0.03 | |

| Δ Control | −2.60 | 2.60 | −2.60 | 2.28 | −3.29 | 1.98 | −3.12 | 2.55 | |||||

| Satisfaction | Microfracture | 7.91 | 1.47 | 0.49 | 7.42 | 1.84 | 0.51 | 7.31 | 2.02 | 0.01 | 6.91 | 2.42 | 0.13 |

| Control | 8.20 | 1.72 | 7.83 | 2.28 | 8.47 | 1.77 | 7.73 | 2.68 |

mHHS, Modified Harris Hip Score; NAHS, Non-Arthritic Hip Score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living; HOS-SSS, Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale.

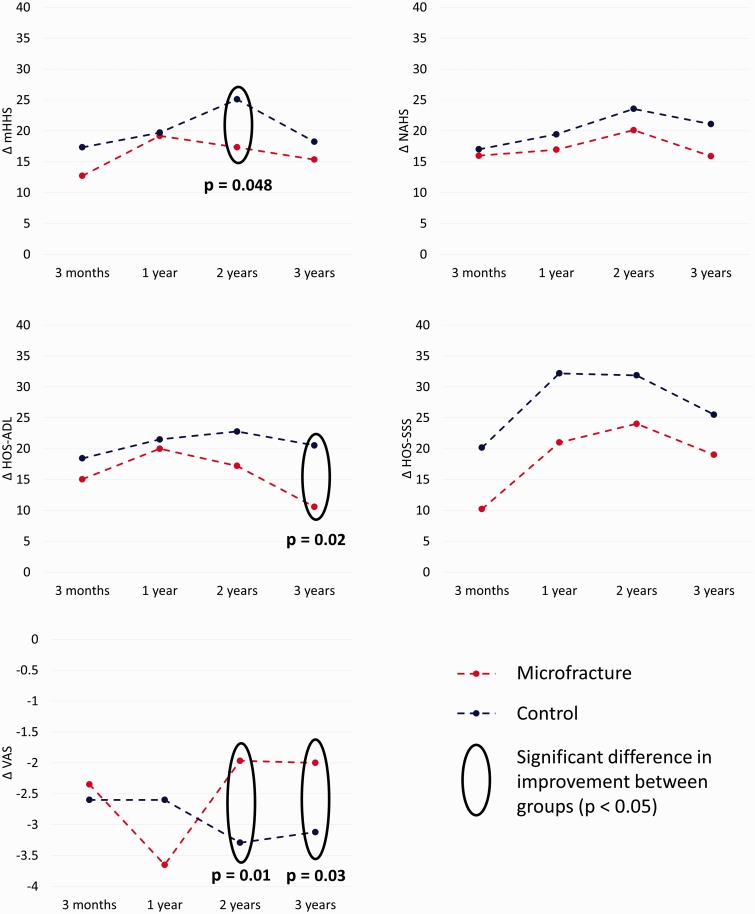

The mean change (delta; Δ) in PRO scores was compared between the two groups (Table VI). The mean change in mHHS and HOS-ADL was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the microfracture group compared with the control group at 2- and 3-year follow-up, respectively. The mean change in VAS scores was also significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the microfracture group compared with the control group at 2 and 3 years post-operatively. Furthermore, the biggest change was observed in all PRO scores at 3 months post-operatively in both groups after which point, it plateaued in both groups. Figure 2 shows the mean change in PRO scores for both groups at all the time points.

Fig. 2.

Mean delta values for PRO scores, from preoperative to 3 months, 1, 2 and 3 years for microfracture and control groups. mHHS, Modified Harris Hip Score; NAHS, Non-Arthritic Hip Score; HOS-ADL, Hip Outcome Score-Activities of Daily Living; HOS-SSS, Hip Outcome Score-Sports Specific Subscale; VAS, Visual Analog Score.

Three patients in the microfracture group (8.6%), and one patient in the control group (1.4%) required conversion to a total hip arthroplasty (THA) or HR. Seven patients in the microfracture group (20%) and four patients in the control group (5.7%) required a revision hip arthroscopy. These differences were not significant between the groups as indicated in Table II.

Sixty-one patients (87%) in the control group had acetabular chondral defects, although the extent of the damage was less than in the microfracture group. Using the Outerbridge classification, the control group had 1 patient (1.4%) with no defects, 22 patients (31.4%) with grade I defects, 25 patients (35.7%) with grade II defects, 14 patients (20%) with grade III defects and no patients with grade IV defects. The mean area of the chondral defect was 1.1 cm2 (SD, 1.2 cm2) in the control group and 1.5 cm2 (SD, 1.3 cm2) in the microfracture group. The mean center of the clock-face position was at 13.3 (SD, 0.6) in the control group and 13.3 (SD, 0.8) in the microfracture group. The mean range of the clock-face position, defined as the most anterior position minus the most posterior position, was 2.7 (SD, 1.0) in the control group and 2.3 (SD, 0.8) in the microfracture group. We did not find significant differences between groups in the clock-face position and range of the acetabular chondral lesion (P > 0.1). The area of the lesion was not significantly different between the two groups; however, there was a trend towards a greater area in the microfracture group (P = 0.1). Regression analysis did not reveal any significant correlations between area, clock-face position, or clock-face range of the acetabular chondral lesions and PRO scores at latest follow-up, either in terms of raw scores or delta values, for either group (P > 0.1).

DISCUSSION

The results in this study results suggest that patients with microfracture had statistically significant improvements between pre and post-operative PRO scores at all time points. Examining the post-operative PRO scores at all time points between the microfracture and control groups revealed no statistically significant difference except for the 3-year HOS-ADL, and the 2- and 3-year VAS scores, which were significantly better in the control group. A possible explanation for HOS-ADL showing a statistically significant difference between the groups could be that patients are more attuned to ADLs (as these are more regular activities compared with activities requiring increased performance like sports and exercise) and can detect and comment on changes in these activities more accurately. Naal et al. [26] have shown higher correlation of the HOS-ADL with the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Index and the Oxford Hip Score than the HOS-SSS in patients with hip osteoarthritis. Patient satisfaction was also significantly lower in the microfracture group by 0.81 points. Finally, the mean change in all PRO scores, except HOS-ADL and VAS, was similar between both groups at 3 years post-operatively. The highest change in both groups was noted at 3 months post-operatively.

Steadman et al. [27] have shown that microfracture is cost effective, technically simple, and allows for more treatment options in the future of the joint. Early work on microfracture in the knee has shown improvements in symptoms and function up to 2 years post-operatively with the most gain being made in the first year [28]. Return to sport has been remarkably fast as a result and has been published by Steadman et al. The authors looked at 25 football players undergoing microfracture of the knee and found that 19 of 25 players returned to play in the National Football League at an average 10 months post-operatively [29]. Steadman et al. also published their results recently on alpine skiers undergoing microfracture of the knee and successfully returning to competitive skiing at an average of 13.4 months post-operatively [30].

With such success in the knee, the microfracture technique has also been applied to the hip. To examine the appearance of microfractured lesions in the hip, Philippon et al. [8] looked at nine patients on revision hip arthroscopy at average 20 months after their index procedure, and noted an average 91% of fill in the lesions. These results were echoed by Karthikeyan et al. [7] who looked at 20 patients undergoing revision hip arthroscopy at average 17 months after index procedure and noted an average 96% fill in acetabular defects that had been microfractured in 19 patients.

PRO scores in patients undergoing microfracture of the hip were reported by Byrd et al., who examined 207 hips treated for cam impingement arthroscopically with at least 12-month follow-up. Of these, 58 were treated with microfracture for grade IV chondral damage. There was an improvement of 20 points in the mHHS scores in this patient subset [31]. Philippon et al. also looked at the outcomes of 122 patients undergoing hip arthroscopy for FAI and chondrolabral dysfunction. The authors compared 2-year follow-up results between patients undergoing microfracture (n = 25) and those treated without microfracture (n = 65) and found no difference in mHHS scores. This study showed similar results at 3 years post-operatively. The study, however, also showed that there was an increase in VAS scores at 2 and 3 years post-operatively in the microfracture group despite very similar PRO scores using other instruments. The majority of improvement in the PRO scores in both groups was at 3 months post-operatively. However, there was a leveling off in improvement after the first year in all scores, except for VAS scores in the control group, which continued to reduce after the first year post-operatively suggesting continued improvement in pain in patients who did not demonstrate grade IV chondral lesions and thus did not have a microfracture.

It was also noted that 8.6% of patients in the microfracture group and 1.4% of patients in the control group underwent THA/HR. Revision hip arthroscopy was performed in 20% of patients in the microfracture group versus 5.7% of patients in the control group.

The methods of subchondral surgery have been studied in animal models in recent literature with differences noted between microfracture and drilling [32–34]. Although microfracture uses an awl to perforate subchondral bone about 3–4 mm in depth and 3–4 mm apart, drilling with flutes can allow perforations with smaller diameter and greater depth. Chen et al. [32] noted in a rabbit model that microfracture produced fractured and compacted bone around holes compared with drilling which cleanly removed bone to provide channels to marrow stroma with less subchondral damage. Furthermore, the authors did not substantiate the detrimental effect of heat necrosis with drilling [32]. Chen et al. [34] in another rabbit model concluded that microfracture and drilling to the same depth (2 mm) produced similar quantity and quality of cartilage repair. Deeper drilling has been shown to induce a larger region of repairing and remodeling bone [34]. Benthien and Behrens [35] have proposed a subchondral needling procedure to standardize thin subchondral perforations deep into subchondral bone using a new device with favorable clinical results. Although drilling to achieve smaller and deeper channels in subchondral bone can be achieved easily in the knee, the angle needed to obtain this theoretical improved subchondral bone marrow stimulation may be challenging in the hip, relegating one to use more angled microfracture awls instead of drills.

The strengths of this study include its matched-pair control design and the measurement of improvement with four different PRO instruments. The matched-pair control design allowed for reduction in confounding variables prior to data analysis. Four PRO instruments were used to address previous evidence in the literature suggesting that no single PRO instrument is adequate for assessing outcomes in hip arthroscopy [11,12].

There are several limitations of this study. First, there was an absence of a group showing the natural course of grade IV chondral damage. The control group was regarded as those patients not demonstrating grade IV chondral damage and hence not undergoing microfracture. Comparison of patients undergoing microfracture with those treated conservatively upon diagnosis of grade IV chondral damage during arthroscopy would provide a more vigorous comparison, thereby truly capturing the change in clinical outcomes with microfracture. Second, an average of 3-year follow-up is still considered short-term follow-up of this patient cohort. Further studies at the senior author’s institution are underway focusing on longer-term follow-up of patients undergoing microfracture. Third, the groups were not matched on Tönnis grade. There were 16 patients (46%) with Tönnis grade 1 changes in the microfracture group versus 20 patients (29%) with Tönnis grade 1 changes in the control group. Fourth, the acetabular crossover sign was used as a matching criterion, which has subjective variability. Zaltz et al. [36] have suggested that the crossover sign has been shown to overestimate acetabular retroversion and may be frequently present on AP pelvis radiographs in the absence of retroversion. To reduce this possibility, a CT scan could be used to define acetabular version. Further radiographic measurements like the presence or absence of cam lesions, dysplasia and anterior inferior iliac spine morphology could also be considered as matching criteria. However, these could have potentially limited the number of patients in the control group that could be matched to the microfracture group successfully. Last, MRI assessment of the lesion after microfracture and biopsy assessment of the lesion in revision hip arthroscopies would add to the understanding of the physiological response and imaging characteristics after microfracture.

CONCLUSION

This study showed that patients undergoing microfracture during hip arthroscopy had no statistically significant difference in mHHS, NAHS and HOS-SSS scores when compared with the control group at an average 3 years post-operatively. There was a statistically significant decrease in HOS-ADL scores and increase in VAS scores in the microfracture group at 3 years post-operatively. Both groups showed significant improvement in all PRO scores except HOS-ADL at 3 years after surgery. Microfracture in the hip helps patients achieve favorable outcomes of their hip with similar results to a matched cohort of patients based on age, gender, acetabular crossover, workman’s compensation claim and labral treatment, who may have chondral lesions that did not warrant microfracture.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the American Hip Institute, though no funding was received directly for this work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hunter W. On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages. Philos Trans R Soc 1743; 42: 514 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Buckwalter JA. Articular cartilage: injuries and potential for healing. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998; 28: 192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedi A, Feeley BT, Williams RJ., 3rd Management of articular cartilage defects of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010; 92: 994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yen YM, Kocher MS. Chondral lesions of the hip: microfracture and chondroplasty. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2010; 18: 83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Arthroscopic intervention in early hip disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004; 429: 157–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domb BG, El Bitar YF, Lindner D, et al. Arthroscopic hip surgery with a microfracture procedure of the hip: clinical outcomes with two-year follow-up. Hip Int 2014; 24: 448–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karthikeyan S, Roberts S, Griffin D. Microfracture for acetabular chondral defects in patients with femoroacetabular impingement: results at second-look arthroscopic surgery. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 2725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, et al. Can microfracture produce repair tissue in acetabular chondral defects?. Arthroscopy 2008; 24: 46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christensen CP, Althausen PL, Mittleman MA, et al. The nonarthritic hip score: reliable and validated. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003; 75–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin RL, Philippon MJ. Evidence of validity for the hip outcome score in hip arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 2007; 23: 822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lodhia P, Slobogean GP, Noonan VK, et al. Patient-reported outcome instruments for femoroacetabular impingement and hip labral pathology: a systematic review of the clinimetric evidence. Arthroscopy 2011; 27: 279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tijssen M, van Cingel R, van Melick N, et al. Patient-reported outcome questionnaires for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review of the psychometric evidence. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011; 12: 117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Domb BG, Gui C, Lodhia P. How much arthritis is too much for hip arthroscopy: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 2015; 31: 520–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Diaz-Ledezma C, Novack T, Marin-Pena O, et al. The relevance of the radiological signs of acetabular retroversion among patients with femoroacetabular impingement. Bone Joint J 2013; 95B: 893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Outerbridge RE. The etiology of chondromalacia patellae. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1961; 43B: 752–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konan S, Rayan F, Meermans G, et al. Validation of the classification system for acetabular chondral lesions identified at arthroscopy in patients with femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011; 93: 332–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Domb BG, Stake CE, Lindner D, et al. Revision hip preservation surgery with hip arthroscopy: clinical outcomes. Arthroscopy 2014; 30: 581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy: the supine position. Instruct Course Lect 2003; 52: 721 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byrd JW. Hip arthroscopy by the supine approach. Instruct Course Lect 2006; 55: 325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly BT, Weiland DE, Schenker ML, et al. Arthroscopic labral repair in the hip: surgical technique and review of the literature. Arthroscopy 2005; 21: 1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Domb BG, Philippon MJ, Giordano BD. Arthroscopic capsulotomy, capsular repair, and capsular plication of the hip: relation to atraumatic instability. Arthroscopy 2013; 29: 162–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta A, Redmond JM, Hammarstedt JE, et al. Arthroscopic decompression of central acetabular impingement with notchplasty. Arthrosc Tech 2014; 3: e555–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blankenbaker DG, De Smet AA, Keene JS, et al. Classification and localization of acetabular labral tears. Skeletal Radiol 2007; 36: 391–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Philippon MJ, Stubbs AJ, Schenker ML, et al. Arthroscopic management of femoroacetabular impingement: osteoplasty technique and literature review. Am J Sports Med 2007; 35: 1571–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larson CM, Giveans MR, Stone RM. Arthroscopic debridement versus refixation of the acetabular labrum associated with femoroacetabular impingement: mean 3.5-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2012; 40: 1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naal FD, Impellizzeri FM, von Eisenhart-Rothe R, et al. Reproducibility, validity, and responsiveness of the hip outcome score in patients with end-stage hip osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 2012; 64: 1770–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Steadman JR, Rodkey WG, Briggs KK. Microfracture: Its history and experience of the developing surgeon. Cartilage 2010; 1: 78 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blevins FT, Steadman JR, Rodrigo JJ, et al. Treatment of articular cartilage defects in athletes: an analysis of functional outcome and lesion appearance. Orthopedics 1998; 21: 761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steadman JR, Miller BS, Karas SG, et al. The microfracture technique in the treatment of full-thickness chondral lesions of the knee in National Football League players. J Knee Surg 2003; 16: 83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Steadman JR, Hanson CM, Briggs KK, et al. Outcomes after knee microfracture of chondral defects in alpine ski racers. J Knee Surg 2014; 27: 407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byrd JW, Jones KS. Arthroscopic femoroplasty in the management of cam-type femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009; 467: 739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen H, Chevrier A, Hoemann CD, et al. Characterization of subchondral bone repair for marrow-stimulated chondral defects and its relationship to articular cartilage resurfacing. Am J Sports Med 2011; 39: 1731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen H, Sun J, Hoemann CD, et al. Drilling and microfracture lead to different bone structure and necrosis during bone-marrow stimulation for cartilage repair. J Orthop Res 2009; 27: 1432–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen H, Hoemann CD, Sun J, et al. Depth of subchondral perforation influences the outcome of bone marrow stimulation cartilage repair. J Orthop Res 2011; 29: 1178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benthien JP, Behrens P. Reviewing subchondral cartilage surgery: considerations for standardised and outcome predictable cartilage remodelling: a technical note. Int Orthop 2013; 37: 2139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaltz I, Kelly BT, Hetsroni I, et al. The crossover sign overestimates acetabular retroversion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013; 471: 2463–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]