Coastal California regularly experiences blooms of Synechococcus cyanobacteria. We found that black perch exposed to one strain (CC9311), but not another (CC9902), spent more time in the dark area of a tank, and moved less. Our results demonstrate that blooms of specific strains of marine cyanobacteria can differentially affect fish.

Keywords: Fish physiology, harmful algal bloom, scototaxis

Abstract

Coastal California experiences large-scale blooms of Synechococcus cyanobacteria, which are predicted to become more prevalent by the end of the 21st century as a result of global climate change. This study investigated whether exposure to bloom-like concentrations of two Synechococcus strains, CC9311 and CC9902, alters fish behaviour. Black perch (Embiotoca jacksoni) were exposed to Synechococcus strain CC9311 or CC9902 (1.5 × 106 cells ml−1) or to control seawater in experimental aquaria for 3 days. Fish movement inside a testing arena was then recorded and analysed using video camera-based motion-tracking software. Compared with control fish, fish exposed to CC9311 demonstrated a significant preference for the dark zone of the tank in the light–dark test, which is an indication of increased anxiety. Furthermore, fish exposed to CC9311 also had a statistically significant decrease in velocity and increase in immobility and they meandered more in comparison to control fish. There was a similar trend in velocity, immobility and meandering in fish exposed to CC9902, but there were no significant differences in behaviour or locomotion between this group and control fish. Identical results were obtained with a second batch of fish. Additionally, in this second trial we also investigated whether fish would recover after a 3 day period in seawater without cyanobacteria. Indeed, there were no longer any significant differences in behaviour among treatments, demonstrating that the sp. CC9311-induced alteration of behaviour is reversible. These results demonstrate that blooms of specific marine Synechococcus strains can induce differential sublethal effects in fish, namely alterations light–dark preference behaviour and motility.

Introduction

Phytoplanktonic organisms are major primary producers that are essential components of aquatic ecosystems. In certain environmental conditions, including anthropogenic pollution, certain species of phytoplankton can achieve dense populations that may be harmful for other aquatic life due to their production of toxic secondary metabolites and/or generation of hypoxic or anoxic conditions. These phenomena, known as harmful algal blooms, can be caused by many diverse marine and freshwater phytoplanktonic species, including cyanobacteria, dinoflagellates and diatoms (Landsberg, 2002). In some cases, the effects of harmful algal blooms are due to toxins that produce neurological, gastrointestinal or hepatic problems. For example, the dinoflagellate Karenia brevis, which is responsible for the typical ‘red tides’, secretes brevetoxin that can bioaccumulate in tissues of consumer species and eventually affect humans (Watkins et al., 2008). Other toxins produced by phytoplanktonic organisms are domoic acid (a neurotoxin produced by some diatoms of the genus Pseudo-nitzschia), saxitoxin (a neurotoxin produced by some marine dinoflagellates and freshwater cyanobacterial strains) and microcystins (hepatotoxins produced almost exclusively by some freshwater cyanobacterial strains; Landsberg, 2002; Salierno et al., 2006; Bakke and Horsberg, 2007; O'Neil et al., 2012; Hackett et al., 2013). As toxin-producing phytoplanktonic species can be very abundant in certain marine environments, they have the potential to affect marine life negatively.

Marine Synechococcus are unicellular cyanobacteria that are abundant throughout the world's oceans and are significant primary producers in coastal environments, where they occupy an important position at the base of the marine food web (Johnson and Sieburth, 1979; Waterbury et al., 1986; Olson et al., 1990; Zwirglmaier et al., 2008; Flombaum et al., 2013). The Synechococcus genus is ecologically and genetically diverse and is composed of multiple ‘clades’ or species (Waterbury et al., 1986; Ferris and Palenik, 1998; Tai and Palenik, 2009; Ahlgren and Rocap, 2012). The four best-understood Synechococcus clades, I–IV, are found in distinct environments throughout the global ocean (Scanlan et al., 2009). Clades I and IV are often found together and typically dominate temperate coastal environments, including the coastal Southern California Bight (Brown and Fuhrman, 2005; Zwirglmaier et al., 2008; Tai and Palenik, 2009; Tai et al., 2011). These are the two predominant clades in the Synechococcus blooms measured at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography Pier (La Jolla, CA, USA) in late spring, which last ∼1 week and show peak abundances around 6 × 105 cells ml−1 (Tai and Palenik, 2009). Clade IV is typically more abundant throughout the year, whereas clade I can become dominant just before the annual spring bloom (Tai and Palenik, 2009; Tai et al., 2011).

Despite the ecological importance of marine Synechococcus, very little is known about their toxic effects on other marine organisms. Some marine intertidal Synechococcus strains from the Portuguese coast, which do not belong to clades I–IV, produce substances with neurotoxic effects in mice, such as decreased respiratory activity and a general loss of equilibrium (Martins et al., 2005). Some Portuguese coastal Synechococcus strains also produce substances with negative effects on invertebrates (Martins et al., 2007); however, the identity of these compounds is unknown. Recently, certain Southern Californian Synechococcus strains have been reported to inhibit the growth of other Synechococcus strains, very probably due to secreted toxins or secondary metabolites (Leao et al., 2012; Paz-Yepes et al., 2013). Specifically, Synechococcus sp. CC9311 from clade I inhibited the growth of sp. WH8102 by unknown secreted molecules. However, it is not known whether this Synechococcus strain produces molecules that are also harmful to animals.

The light–dark preference test, also known as the scototaxic test, is a common method to measure anxiety in fish (Maximino et al., 2010) and whether pharmacological compounds alter anxiety (Gerlai et al., 2006; Mathur and Guo, 2011; Maximino et al., 2011). Most of these studies have been performed on freshwater fish; however, this test has recently been used to examine alterations of behaviour in marine fish as well (Hamilton et al., 2014). In that study, exposure to elevated CO2/low-pH seawater increased dark preference in juvenile rockfish (Sebastes diploproa), a behavioural change that was linked to increased anxiety.

The aim of this study was to determine whether exposure to bloom-like concentrations of two Synechococcus strains (sp. CC9311 from clade I and sp. CC9902 from clade IV) alter the behaviour of black perch (Embiotoca jacksoni), which are native to coastal California.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Synechococcus sp. strains CC9311 (clade I) and CC9902 (clade IV) were grown in SN medium (Waterbury and Willey, 1988) made with seawater from the Scripps Pier (Scripps Institution of Oceanography, La Jolla, CA, USA). Cyanobacterial cultures were incubated at 25°C with a constant illumination of 40 μE m−2 s−1 and were maintained as 1 l cultures in 2.8 l glass flasks with regular stirring. These strains have been kept in culture since their isolation in the 1990s [1993 for CC9311 (Palenik et al., 2006) and 1999 for CC9902 (Dufresne et al., 2008)].

Aliquots of the stocks with a concentration of ∼1 × 108 cells ml−1 were added to seawater in aquaria to reach a final concentration of ∼1.5 × 106 cells ml−1. The final concentration was estimated from cell counts using a Petroff-Hausser chamber (Hausser Scientific, Horsham, PA, USA) under an epifluorescence microscope. This concentration is comparable to that observed in blooms around the Scripps Pier (Tai and Palenik, 2009) and is the same order of magnitude that has been used in other laboratory studies demonstrating ecologically relevant results (Paz-Yepes et al., 2013). Using a conversion factor of 175 fg carbon cell−1 for Synecochoccus (Burkhill et al., 1993), the concentration of carbon in each tank due to Synecochoccus was 2.6 × 104 mg carbon ml−1. The concentration of cyanobacteria in each aquarium was calculated daily and adjusted as needed to maintain similar concentrations among treatment groups, as described above. The control group was exposed to SN culture medium at the same concentration used for the Synechococcus groups. Light transmittance, measured in new cultures with the same cyanobacterial density, was identical in the two cultures and <10% lower than the SN control (Supplementary Fig. 1a and b). All cultures look similar to the naked eye (Supplementary Fig. 1c).

Animal collection and housing

Wild black perch (Embiotoca jacksoni) were caught off the coast of San Diego (CA, USA) and housed in groups of 8–12 in three 30 l glass aquaria in the same room as the testing arena described below. Fish average total length was 99.1 ± 6.7 mm (range, 73.5–145.4 mm) and their average weight was 24.0 ± 5.2 g (range, 6.5–68.7 g; n = 52). Fish were maintained on a 12 h–12 h light–dark cycle and fed dry fish pellets (New Life Spectrum Small Fish Formula, New Life International Inc., Homestead, FL, USA) ad libitum once daily. On experimental trial days, fish were fed after behavioural testing.

To prevent build-up of waste products, depletion of nutrients and major changes in seawater chemistry and to keep Synechococcus abundance relatively constant, one-third of the seawater in each tank was replaced with fresh seawater daily. Water temperature (19.1 ± 0.2°C), pH (8.00 ± 0.02) and dissolved oxygen (9.92 ± 0.06 mg l−1) in each tank were measured several times daily; none of these variables differed significantly among treatments.

A total of 8–12 fish were randomly assigned to each of three treatment groups: (i) Synechococcus sp. CC9311 (clade I); (ii) Synechococcus sp. CC9902 (clade IV); and (iii) control. Behavioural testing as described below occurred on day 3 of the exposures.

Behavioural testing

In order to determine whether the effects of Synechococcus strains CC9311 and CC9902 on fish behaviour differed from each other or from the control treatment, we conducted a series of behavioural experiments using the light–dark (scototaxic) test. The light–dark testing arena was created by affixing panels of white and black non-reflective and non-toxic foam board to the sides and bottom of a ∼67 l glass aquarium (74 cm × 30 cm × 30 cm). Ambient seawater was used to fill the arena to a depth of 13 cm, and the seawater was replaced after every 10 testing trials. All testing took place between 09.00 and 18.00 h in a sound-controlled room with moderate overhead lighting. White corrugated cardboard was placed around the arena to minimize shadows in the testing arena and to eliminate external visual stimuli.

At the beginning of each trial, a fish was netted from one of the three treatment tanks and gently placed into the centre of the arena, perpendicular to the long axis to avoid biasing (Holcombe et al., 2013, 2014; Hamilton et al., 2014). Trials began within 5 s of placing the fish into the arena and were 10 min in duration. Fish movement was detected, recorded and analysed using a monochrome CCD camera located ∼1.5 m above the arena and the differencing method in EthoVison XT version 7.0 (Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA). For each fish, we quantified time spent in the light and dark zones (in seconds), time spent in the middle zone (in seconds; 59 cm × 20 cm area in the centre of the arena) as a proxy for thigmotaxis, number of zone transitions, average velocity (in centimetres per second), meandering (in degress per second) and time spent immobile (in seconds; 5% threshold, as defined by Pham et al., 2009).

This exposure protocol was then repeated on a second batch of fish, yielding two experimental sets (ES1 and ES2). In the second experiment, we additionally determined whether the fish could recover from the effects of Synechococcus strains CC9311 by placing all groups of fish into normal flowing seawater and repeating behavioural testing 3 days later.

All animal handling and experiments followed approved Animal Care Protocol S10320.

Statistical analysis

All data sets were tested for normality with the D'Agostino–Pearson omnibus test. All normally distributed data passed Bartlett's test for equal variance. Time spent in the dark zone was analysed with one-sample t tests (for normally distributed data) or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests to assess statistically significant differences from 300 s, as commonly used in these types of studies (Maximino et al., 2007; Cripps et al., 2011; Mathur and Guo, 2011; Holcombe et al., 2013; Hamilton et al., 2014). For all other variables, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Tukey's HSD post hoc test (for normally distributed data) or Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests were used, with α = 0.05 and 95% confidence intervals, to assess statistically significant differences among treatment groups. To analyse within-group comparisons, Student's unpaired t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests were used. Data were analysed with GraphPad Prism 4.0B (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA) and are presented as mean values ± SEM. Power analyses were performed for average velocity, meandering and time spent immobile using http://www.statisticalsolutions.net/pss_calc.php.

Results

Effects of 3 day Synechococcus exposure

None of the variables analysed (time spent in the dark zone or middle zone, number of zone transitions, average velocity, meandering and time spent immobile) were significantly different between the two experimental sets of fish (ES1 and ES2) for any of the three treatments (one-way ANOVAs with Tukey's HSD post hoc test or Kruskal–Wallis with Dunnett's multiple comparison tests, P > 0.05 for all pairwise comparisons); therefore, data from ES1 and ES2 were pooled for subsequent analyses.

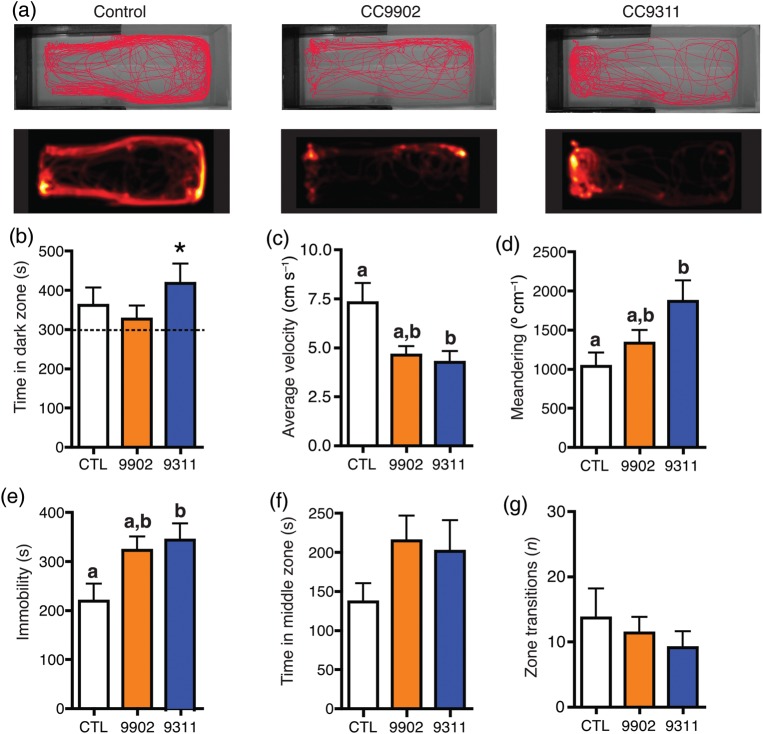

After 3 days of exposure to treatment conditions, there was no significant preference for the dark zone in either the control group (352 ± 43 s, P = 0.1342, n = 15) or the Synechococcus sp. CC9902 group (327 ± 34 s, P = 0.4404, n = 13; Fig. 1a and b), but the Synechococcus sp. CC9311 group exhibited a significant preference for the dark zone (418 ± 50 s, P = 0.0327, n = 16; in all cases, one-sample t test, difference from 300 s; see Supplementary Videos 1–3).

Figure 1:

Exposure to Synechococcus for 3 days. (a) Fish from the control, Synechococcus sp. CC9902 and Synechococcus sp. CC9311 groups were individually placed in the light–dark preference test arena, and their location was recorded for 900 s. The upper trace illustrates the movement of one representative fish from each treatment over the duration of the trial. The heatmap (below) represents the movement of the same fish throughout the trial and is proportional to the time the fish spent in each pixel. (b) Control (CTL) and Synechococcus sp. CC9902 (9902) fish did not have a zone preference, whereas Synechococcus sp. CC9311 (9311) fish spent significantly more time in the dark zone, indicating increased anxiety. *Statistically significant difference from 300 s, P < 0.05. (c) Average velocity was significantly lower in the CC9311 group, but not in the CC9902 group, compared with the control group, nor in the CC9311 group compared with the CC9902 group. (d) Meandering was significantly greater in the CC9311 group, but not in the CC9902 group, compared with the control group, nor in the CC9311 group compared with the CC9902 group. (e) Immobility was significantly higher in the CC9311 group, but not in the CC9902 group, compared with the control group, nor in the CC9311 group compared with the CC9902 group. (f and g) There were no significant differences among groups in time spent in the middle zone or number of zone transitions. For b–g, control (n = 15), CC9902 (n = 13) and CC9311 (n = 16). Letters indicate statistically significant differences between the treatments (the same letter indicates lack of statistically significant differences).

Average velocity was significantly lower in the Synechococcus sp. CC9311 group (4.3 ± 0.6 cm s−1, n = 16), but not in the Synechococcus sp. CC9902 group (4.6 ± 0.5 cm s−1, n = 13), compared with the control group (7.3 ± 1.0 cm s−1, n = 15; Kruskal–Wallis test, H(2, 41) = 7.379, P = 0.0250, followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison post hoc test, P < 0.05; Fig. 1c). Furthermore, meandering was significantly higher in the Synechococcus sp. CC9311 group (1815 ± 281° cm−1, n = 16), but not in the Synechococcus sp. CC9902 group (1332 ± 170° cm−1, n = 13), compared with the control group (1037 ± 175° cm−1, n = 15; one-way ANOVA, F(2, 41) = 4.014, P = 0.0256, followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc test, P < 0.05; Fig. 1d). Time spent immobile was significantly longer in the Synechococcus sp. CC9311 group (349 ± 34 s, n = 16), but not in the Synechococcus sp. CC9902 group (323 ± 28 s, n = 13), compared with the control group (219 ± 36 s, n = 15; one-way ANOVA, F(2, 41) = 3.356, P = 0.0193, followed by Tukey's HSD post hoc test, P < 0.05; Fig. 1e).

Time spent in the middle zone was not significantly different among the three groups (CC9311, 201 ± 40 s, n = 16; CC9902, 215 ± 32 s, n = 13; and control, 137 ± 34 s, n = 15; Kruskal–Wallis test, H(2, 41) = 3.462, P > 0.05; Fig. 1f), indicating that there were no differences in thigmotaxis (time spent near the tank walls) among groups. The number of transitions between the light and dark zones was also not significantly different among groups (CC9311, 9 ± 3, n = 16; CC9902, 11 ± 3, n = 13; and control, 14 ± 5, n = 15; Kruskal–Wallis test, H(2, 41) = 1.141, P > 0.05; Fig. 1g).

Given that the average velocity, meandering and immobility in fish exposed to CC9902 were not significantly different from either the control or the CC9311 group, we performed two-tailed post hoc power analyses to calculate the possibility of committing a type II statistical error. These analyses indicated that our statistical tests had a power of 0.76 for average velocity, 1.00 for meandering and 0.77 for immobility. In other words, the chances of not detecting a significant difference due to sample size and variability were 24, 0 and 23%, respectively.

Recovery in normal seawater

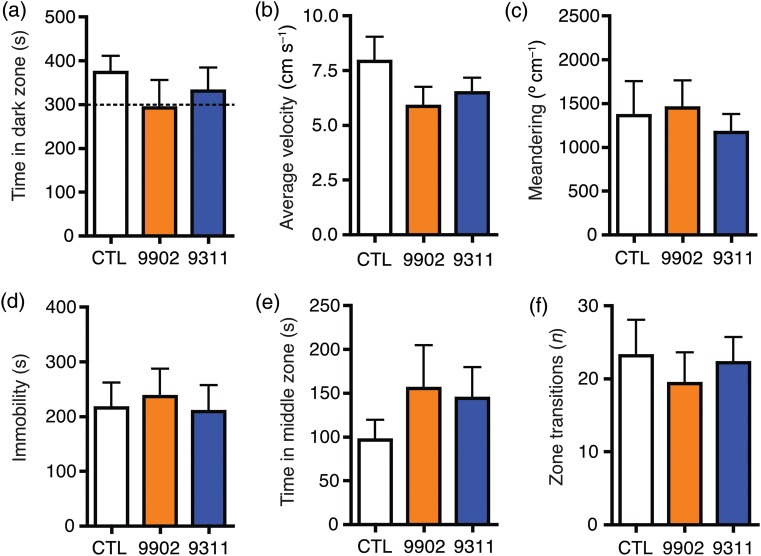

To investigate whether the effects of Synechococcus strains CC9311 and CC9902 were reversible, fish from all groups were placed in normal, flowing seawater and their behaviour was tested again 3 days later. Control fish behaved in an identical manner to the previous trial. In addition, fish that had previously been exposed to Synechococcus did not show any significant differences in any of the variables analysed [time spent in the dark zone (one-sample t-test, difference from 300 s, P > 0.05); average velocity (one-way ANOVA, F(2, 22) = 1.296, P > 0.05); meandering (one-way ANOVA, F(2,22) = 0.2443, P > 0.05); time spent immobile (one-way ANOVA, F(2, 22) = 0.0907, P > 0.05); time spent in the middle zone (Kruskal–Wallis test, H(2, 22) = 0.4442, P > 0.05); and number of zone transitions (one-way ANOVA, F(2, 22) = 0.2257, P > 0.05; Fig. 2)].

Figure 2:

Recovery after Synechococcus exposure. After the 3 day exposure to Synechococcus sp. CC9902, Synechococcus sp. CC9311 or control conditions, all groups were placed back into normal, flowing seawater and retested after 3 days. There were no longer significant differences in time spent in the dark zone (a), average velocity (b) and meandering (c) in the CC9311 group compared with the control group. There were also no significant differences among groups in immobility (d), time spent in the middle zone (e) and number of zone transitions (f).

Finally, we performed a within-group comparison of the effects of Synechococcus sp. CC9311 on day 3 of exposure vs. recovery. There were significant differences in the time spent in the dark zone, average velocity, meandering, time spent immobile and number of zone transitions (Student's unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.05 for all pairwise comparisons; Table 1). Similar within-group comparisons for both the Synechococcus sp. CC9902 group and the control group demonstrated no significant change in any variable (Table 1).

Table 1:

Comparison of day 3 of exposure with recovery for each group in the second experiment (ES2)

| Control |

Synechococcus sp. CC9902 |

Synechococcus sp. CC9311 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 3 of exposure (n = 8) | Recovery (n = 7) | Day 3 of exposure (n = 9) | Recovery (n = 9) | Day 3 of exposure (n = 10) | Recovery (n = 9) | |

| Time spent in dark zone (s) | 365 ± 70 | 373 ± 38 | 344 ± 48 | 292 ± 64 | 448 ± 60 | 331 ± 54* |

| Mean velocity (cm s−1) | 6.5 ± 1.6 | 7.9 ± 1.1 | 4.4 ± 0.7 | 5.9 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 6.5 ± 0.7* |

| Meandering (° cm−1) | 1381 ± 261 | 1363 ± 391 | 1473 ± 229 | 1450 ± 312 | 2110 ± 351 | 1169 ± 211* |

| Time spent immobile (s) | 293 ± 51 | 216 ± 46 | 361 ± 28 | 237 ± 51 | 374 ± 40 | 209 ± 48* |

| Time spent in middle zone (s) | 111 ± 24 | 97 ± 23 | 215 ± 43 | 155 ± 49 | 135 ± 42 | 144 ± 35 |

| Number of zone transitions | 20.3 ± 7.7 | 23.1 ± 4.9 | 14.0 ± 3.7 | 19.3 ± 4.3 | 7.2 ± 2.8 | 22.2 ± 3.5** |

*Time spent in the dark zone: statistically significant difference from 300 s, P < 0.05. All other parameters: statistically significant differences among treatments (Student's unpaired t tests or Mann–Whitney U tests, P < 0.05). **P < 0.01.

Discussion

Given that different Synechococcus strains may produce different toxins and secondary metabolites (Leao et al., 2012; Paz-Yepes et al., 2013) and that toxins from other planktonic organisms have been shown to induce neurological and behavioural changes in other aquatic organisms (Baganz et al., 2004; Zagatto et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013; Ferrâo-Filho et al., 2014), we hypothesized that exposure to two distinct Synechococcus strains would differentially alter fish behaviour and locomotion. Our results demonstrated a significant effect of Synechococcus strain CC9311, but not CC9902, on dark preference of black perch (E. jacksoni). Furthermore, exposure to both Synechococcus strains decreased average velocity, whereas it increased meandering and immobility. However, the effects were statistically significantly different from control fish only in the CC9311 group.

There are at least two potential, not mutually exclusive, explanations for the effect of Synechococcus sp. CC9311 on the alteration of fish behaviour, as follows: (i) CC9311 may produce a toxin that is capable of entering the circulatory system of the fish and crossing the blood–brain barrier to exert a direct effect on neuronal activity, resulting in decreased velocity and increased dark preference; and (ii) CC9311 may produce a toxin(s) or secondary metabolite(s) that induces some other negative effect (i.e. sickness), and the stress response of the fish is to move into a safer area (dark zone) and to move less in order to promote recovery. In any case, the end result is clear; exposure to Synechococcus sp. CC9311 for 3 days induced a change in the decision-making of the fish, altered locomotion and increased anxiety behaviour.

Our results indicate that Synechococcus sp. CC9311 has a significant effect on the behaviour of marine fish at a concentration of ∼1.5 × 106 cells ml−1 after a 3 day exposure. Although exposure to Synechococcus sp. CC9902 for the same amount of time did not induce any significant changes in light–dark preference in comparison to the control group, it did affect some other variables with a similar trend in comparison to CC9311-treated fish. Specifically, average velocity was reduced, while meandering and time spent immobile were increased. Although these variables were not significantly different compared with control fish, they were also not significantly different compared with fish exposed to CC9311 (Fig. 1). Additionally, power analyses indicated that the possibility of type II statistical error for each of these variables was non-existent to relatively low (24% for average velocity, 0% for meandering and 23% for immobility). Thus, while we cannot rule out the possibility that CC9902 mildly affects a subset of the parameters tested, we confidently conclude that CC9311 induces differential effects on black perch in our experimental conditions. This conclusion is further strengthened by the fact that when fish were placed back into clean seawater, the only group to show a significant change in behaviour (‘recovery’) was the CC9311 group, again indicating a lesser effect of CC9902.

There are at least three potential explanations for these results, as follows: (i) the two cyanobacterial strains produce the same toxins, but CC9311 produces these toxins in larger amounts; (ii) CC9311 and CC9902 produce different toxins that induce different effects in fish; and (iii) CC9311 and CC9902 produce some toxins in common, but CC9311 produces additional toxins responsible for the differential effects on fish behaviour (for example, dark preference).

Although the environment can also have profound effects on fish behaviour (Magnhagen, 2008), these effects are typically seen upon light disturbances much greater than in our study (e.g. Long and Rosenqvist, 1998; Järvenpää and Lindström, 2004; Wong et al., 2007). Regardless, the two Synechococcus cultures induced differential behavioural effects in our experiments, so at the very least, light cannot explain the effects of CC9311. Thus, we can rule out illumination differences caused by the cyanobacteria as the cause for the altered behaviour. Other factors to consider are O2, CO2 and pH levels. While we kept those factors constant by vigorous aeration and daily water changes, Synechococcus blooms almost certainly will change those parameters in the wild, which could have synergistic effects with the presumed toxin(s) or metabolite(s) on fish behaviour.

The effects of exposure to Synechococcus sp. CC9311 on black perch are similar to the locomotor deficits observed in freshwater killifish and zebrafish due to toxins from harmful algal blooms (Salierno et al., 2006; Kist et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2013) and to the alteration of swimming behaviour in larval herring exposed to saxitoxin (Lefebvre et al., 2005) and in crustaceans exposed to cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (Ferrâo-Filho et al., 2014). These behavioural changes may be explained by several generic mechanisms. In response to toxins, fish may adjust their metabolism to promote biotransformation of the toxin (Zhang et al., 2013); the general decrease in metabolism would decrease energy supply and have a downstream effect on overall movement. Another explanation might be the direct effect of a neurotoxin. For example, paralytic shellfish poisons contain aphatoxins that decrease the action of acetylcholinesterase in the brain (Zhang et al., 2013); the resulting abnormally high acetylcholine levels would have multiple effects in the central nervous system. Many other neurotoxins present in the marine environment, including saxitoxin, brevetoxin and domoic acid, have also been suggested to alter cognitive functioning by differentially altering metabolic activity in the brain (Bakke and Horsberg, 2007); however, no behavioural tests have been performed to verify the presumed change in cognitive ability. In summary, harmful algal blooms producing toxins are capable of inducing either an activation or a depression of activity throughout the brain (Salierno et al., 2006), which could have widespread neurological implications.

The sublethal effects of environmental toxins, such as alterations of fish behaviour, are not as easily detectable as their lethal effects. However, behavioural changes can have significant effects on the life history of an animal. As shown in this and previous studies (Maximino et al., 2010; Hamilton et al., 2014), the light–dark test is a valuable method for assessing behavioural changes in response to environmental stressors by measuring swimming performance parameters, such as velocity, meandering and immobility. Importantly, this test is also capable of examining location-preference behaviour, which is a proxy for anxiety stress. Therefore, the use of the light–dark test is a valuable tool to detect and quantify sublethal effects caused by diverse stressors in marine fish.

The concentrations of Synechococcus spp. used in this study were consistent with concentrations recorded during blooms off the coast of California (Tai and Palenik, 2009; Tai et al., 2011). Predictions based on global climate change scenarios (Flombaum et al., 2013) suggest that Synechococcus blooms may reach higher concentration peaks by the end of the 21st century, which would enhance sublethal effects, such as those observed in this study. As part of their osmoregulatory mechanism, marine fish must drink seawater almost constantly in order to absorb water across the intestine, thus counteracting dehydration (Smith, 1930). Therefore, during blooms, marine fish have no option but also to ingest Synechococcus, regardless of their feeding behaviour. Additionally, putative water-borne toxins may be absorbed through the gills, eyes and skin.

Future research should investigate whether the results from our laboratory study also apply to the wild, and what the implications of the observed behavioural disturbances are. The changes in light–dark preference and movement patterns induced by Synechococcus exposure could theoretically affect virtually every aspect of fish biology and ecology, including but not limited to feeding, dispersal, reproduction and predation vulnerability. In turn, this research could bring about many more questions. Are all fish species equally affected by exposure to Synechococcus blooms? Do the sublethal effects observed in fish also occur in other marine organisms? Do fish and other motile organisms move away from the location where the bloom takes place? In any case, an important implication to be taken from our study is that predicting potential effects caused by Synechococcus blooms requires determining the abundance of specific Synechococcus strains and not only the total Synechococcus spp. abundance.

Our results demonstrate that the effects of Synechococcus sp. CC9311 exposure on fish behaviour are reversible after a recovery period of 3 days in normal seawater. This implies that the potential impact of CC9311 blooms in nature would be transient. Future research will investigate the exact timing of the recovery, which is likely to take place at some point between a few hours and 3 days.

To our knowledge, this study provides the first evidence that blooms of specific marine Synechococcus strains can induce differential sublethal effects in marine fish. In order to elucidate the mechanism behind the toxicity produced by Synechococcus sp. CC9311 further, it will be necessary to isolate the specific toxin(s) responsible for the effects observed. In the future, it will be valuable to examine the effect of harmful algal blooms on the behaviour of fish in the wild.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at Conservation Physiology online.

Acknowledgements

This work is dedicated to the memory of our friend and colleague Rachel Morrison, who passed away while this manuscript was under review and who will be greatly missed. The authors are grateful to Phil Zerofski (Scripps Institution of Oceanography) for his excellent assistance with aquarium matters and to Dr Jon Shurrin (University of California San Diego) for advice with statistical analyses. This work was supported by Scripps Institution of Oceanography funds and an Alfred P. Sloan Research Fellowship (grant #BR2013-103) to M.T. A MacEwan Arts and Science grant funded T.J.H. J.P.-Y. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) under REA grant agreement no. 275289 and NSF IOS-1021421 (to B.P.).

References

- 1.Ahlgren NA, Rocap G. (2012) Diversity and distribution of marine Synechococcus: multiple gene phylogenies for consensus classification and development of qPCR assays for sensitive measurement of clades in the ocean. Front Microbiol 3: 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baganz D, Staaks G, Pflugmacher S, Steinberg CE. (2004) Comparative study of microcystin-LR-induced behavioral changes of two fish species, Danio rerio and Leucaspius delineatus. Environ Toxicol 19: 564–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakke MJ, Horsberg TE. (2007) Effects of algal-produced neurotoxins on metabolic activity in telencephalon, optic tectum and cerebellum of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Aquat Toxicol 85: 96–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown MV, Fuhrman JA. (2005) Marine bacterial microdiversity as revealed by internal transcribed spacer analysis. Aquat Microb Ecol 41: 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burkhill PH, Leakey RJG, Owens NJP, Mantoura RFC. (1993) Synechococcus and its importance to the microbial foodweb of the northestern Indian Ocean. Deep Sea Res Part II 40: 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cripps IL, Munday PL, McCormick MI. (2011) Ocean acidification affects prey detection by a predatory reef fish. PLoS ONE 6: pe22736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dufresne A, Ostrowski M, Scanlan DJ, Garczarek L, Mazard S, Palenik BP, Paulsen IT, de Marsac NT, Wincker P, Dossat C, et al. (2008) Unraveling the genomic mosaic of a ubiquitous genus of marine cyanobacteria. Genome Biol 9: pR90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferrâo-Filho AS, Soares MC, Lima RS, Magalhaes VF. (2014) Effects of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (cyanobacteria) on the swimming behavior of Daphnia (cladocera). Environ Toxicol Chem 33: 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferris MJ, Palenik B. (1998) Niche adaptation in ocean cyanobacteria. Nature 396: 226–228. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flombaum P, Gallegos JL, Gordillo RA, Rincon J, Zabala LL, Jiao N, Karl DM, Li WK, Lomas MW, Veneziano D, et al. (2013) Present and future global distributions of the marine Cyanobacteria Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 9824–9829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gerlai R, Lee V, Blaser R. (2006) Effects of acute and chronic ethanol exposure on the behavior of adult zebrafish (Danio rerio). Pharmacol Biochem Behav 85: 752–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackett JD, Wisecaver JH, Brosnahan ML, Kulis DM, Anderson DM, Bhattacharya D, Plumley FG, Erdner DL. (2013) Evolution of saxitoxin synthesis in cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates. Mol Biol Evol 30: 70–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton TJ, Holcombe A, Tresguerres M. (2014) CO2-induced ocean acidification increases anxiety in rockfish via alteration of GABAA receptor functioning. Proc Biol Sci 281: 20132509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holcombe A, Howorko A, Powell RA, Schalomon M, Hamilton TJ. (2013) Reversed scototaxis during withdrawal after daily-moderate, but not weekly-binge, administration of ethanol in zebrafish. PLoS ONE 5: pe63319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holcombe A, Schalomon M, Hamilton TJ. (2014) A novel method of drug administration to multiple fish and quantification of the withdrawal response in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). J Vis Exp (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Järvenpää M, Lindström K. (2004) Water turbidity by algal blooms causes mating system breakdown in a shallow-water fish, the sand goby Pomatoschistus minutus. Proc Biol Sci 271: 2361–2365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson PW, Sieburth JM. (1979) Chroococcoid cyanobacteria in the sea: a ubiquitous and diverse phototrophic biomass. Limnol Oceanogr 24: 928–935. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kist LW, Piato AL, da Rosa JG, Koakoski G, Barcellos LJ, Yunes JS, Bonan CD, Bogo MR. (2011) Acute exposure to microcystin-producing cyanobacterium Microcystis aeruginosa alters adult zebrafish (Danio rerio) swimming performance parameters. J Toxicol 2011: 280304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landsberg JH. (2002) The effects of harmful algal blooms on aquatic organisms. Rev Fish Sci 10: 113–390. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leao PN, Engene N, Antunes A, Gerwick WH, Vasconcelos V. (2012) The chemical ecology of cyanobacteria. Nat Prod Rep 29: 372–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lefebvre KA, Elder N, Hershberger PK, Trainer VL, Stehr CM, Scholz NL. (2005) Dissolved saxitoxin causes transient inhibition of sensorimotor function in larval Pacific herring (Clupea harengus pallasi). Mar Biol 147: 1393–1402. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Long KD, Rosenqvist G. (1998) Changes in male guppy courting distance in response to a fluctuating light environment. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 44: 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnhagen C. (2008) Fish Behaviour. Science Publishers, Enfield, NH. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martins R, Pereira P, Welker M, Fastner J, Vasconcelos VM. (2005) Toxicity of culturable cyanobacteria strains isolated from the Portuguese coast. Toxicon 46: 454–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martins R, Fernandez N, Beiras R, Vasconcelos V. (2007) Toxicity assessment of crude and partially purified extracts of marine Synechocystis and Synechococcus cyanobacterial strains in marine invertebrates. Toxicon 50: 791–799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mathur P, Guo S. (2011) Differences of acute versus chronic ethanol exposure on anxiety-like behavioral responses in zebrafish. Behav Brain Res 219: 234–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maximino C, Marques T, Dias F, Cortes FV, Taccolini IB, Pereira PM, Colmanetti R, Gazolla RA, Tavares RI, Rodrigues STK, et al. (2007) A comparative analysis of the preference for dark environments in five teleosts. Int J Comp Psychol 20: 351–367. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maximino C, Marques de Brito T, Dias CA, Gouveia A, Jr, Morato S. (2010) Scototaxis as anxiety-like behavior in fish. Nat Protoc 5: 209–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maximino C, da Silva AW, Gouveia A, Jr, Herculano AM. (2011) Pharmacological analysis of zebrafish (Danio rerio) scototaxis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 35: 624–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Zettler ER, Armbrust EV. (1990) Pigments, size, and distribution of Synechococcus in the North Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Limnol Oceanogr 35: 45–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neil JM, Davis TW, Burford MA, Gobler CJ. (2012) The rise of harmful cyanobacteria blooms: the potential roles of eutrophication and climate change. Harmful Algae 14: 313–334. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Palenik B, Ren Q, Dupont CL, Myers GS, Heidelberg JF, Badger JH, Madupu R, Nelson WC, Brinkac LM, Dodson RJ, et al. (2006) Genome sequence of Synechococcus CC9311: insights into adaptation to a coastal environment. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 103: 13555–13559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paz-Yepes J, Brahamsha B, Palenik B. (2013) Role of a Microcin-C-like biosynthetic gene cluster in allelopathic interactions in marine Synechococcus. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 110: 12030–12035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pham J, Cabrera SM, Sanchis-Segura C, Wood MA. (2009) Automated scoring of fear-related behavior using EthoVision software. J Neurosci Methods 178: 323–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salierno JD, Snyder NS, Murphy AZ, Poli M, Hall S, Baden D, Kane AS. (2006) Harmful algal bloom toxins alter c-Fos protein expression in the brain of killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus. Aquat Toxicol 78: 350–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scanlan DJ, Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Dufresne A, Garczarek L, Hess WR, Post AF, Hagemann M, Paulsen I, Partensky F. (2009) Ecological genomics of marine picocyanobacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 73: 249–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith HW. (1930) The absorption and excretion of water and salts by marine teleosts. Am J Physiol 93: 480–505. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tai V, Palenik B. (2009) Temporal variation of Synechococcus clades at a coastal Pacific Ocean monitoring site. ISME J 3: 903–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tai V, Burton RS, Palenik B. (2011) Temporal and spatial distributions of marine Synechococcus in the Southern California Bight assessed by hybridization to bead-arrays. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 426: 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waterbury JB, Willey JM. (1988) Isolation and growth of marine planktonic cyanobacteria. Methods Enzymol 167: 100–105. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Waterbury JB, Watson SW, Valois F, Franks D. (1986) Biological and ecological characterization of the marine unicellular cyanobacterium Synechococcus. Can Bull Fish Aquat Sci 214: 71–120. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watkins SM, Reich A, Fleming LE, Hammond R. (2008) Neurotoxic shellfish poisoning. Mar Drugs 6: 431–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong BBM, Candolin U, Lindström K. (2007) Environmental deterioration compromises socially enforced signals of male quality in three-spined sticklebacks. Am Nat 170: 184–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zagatto PA, Buratini SV, Aragão MA, Ferrão-Filho AS. (2012) Neurotoxicity of two Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii (cyanobacteria) strains to mice, Daphnia, and fish. Environ Toxicol Chem 31: 857–862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang DL, Hu CX, Li DH, Liu YD. (2013) Zebrafish locomotor capacity and brain acetylcholinesterase activity is altered by Aphanizomenon flos-aquae DC-1 aphantoxins. Aquat Toxicol 138–139: 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zwirglmaier K, Jardillier L, Ostrowski M, Mazard S, Garczarek L, Vaulot D, Not F, Massana R, Ulloa O, Scanlan DJ. (2008) Global phylogeography of marine Synechococcus and Prochlorococcus reveals a distinct partitioning of lineages among oceanic biomes. Environ Microbiol 10: 147–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.