Abstract

The surgical management of breast cancer has undergone continuous and profound changes over the last 40 years. The evolution from aggressive and mutilating treatment to conservative approach has been long, but constant, despite the controversies that appeared every time a new procedure came to light. Today, the aesthetic satisfaction of breast cancer patients coupled with the oncological safety is the goal of the modern breast surgeon.

Breast-conserving surgery with adjuvant radiotherapy is considered the gold standard approach for patients with early stage breast cancer and the recent introduction of “oncoplastic techniques” has furtherly increased the use of breast-conserving procedures.

Mastectomy remains a valid surgical alternative in selected cases and is usually associated with immediate reconstructive procedures.

New surgical procedures called “conservative mastectomies” are emerging as techniques that combine oncological safety and cosmesis by entirely removing the breast parenchyma sparing the breast skin and nipple-areola complex.

Staging of the axilla has also gradually evolved toward less aggressive approaches with the adoption of sentinel node biopsy and new therapeutic strategies are emerging in patients with a pathological positivity in sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The present work will highlight the new surgical treatment options increasingly efficacy and respectful of breast cancer patients.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Conservative surgery, Oncoplastic surgery, Conservative mastectomy, Sentinel node

Introduction

Breast cancer is currently the most common cancer in women worldwide, with demographic trends indicating a continuous increase in incidence. Only in the European Union, it is estimated that by 2020 there will be approximately 394,000 new cases of breast cancer per year and 100,000 deaths (1).

The surgical treatment of breast cancer has undergone continuous and profound changes over the last four decades. Today, the aesthetic satisfaction of breast cancer patients combined with the oncological safety is the goal of the modern breast surgeon.

For patients with early stage breast cancer, breast-conserving surgery followed by radiation therapy has been definitively validated as a safe alternative to radical mastectomy, with similar survival rates, better cosmetic outcomes and acceptable rates of local recurrence. Thanks to the improvements in diagnostic work-up, as well as the wider diffusion of screening programs and efforts in patient and physician education, tumors are more often detected at an early stage, furtherly facilitating the widespread use of breast conserving techniques.

Breast-conserving surgery has been introduced also in the treatment of patients with locally advanced tumors after tumor downsizing with preoperative chemotherapy, with acceptable rates of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence.

When performing breast-conserving surgery all efforts should be made to ensure negative surgical margins in order minimize the risk of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence as they are associated with worse distant-disease-free and breast cancer-specific survival rates. The recent introduction of “oncoplastic techniques”, that may allow more extensive excisions of the breast without compromising the cosmetic results, has furtherly increased the use of breast-conserving procedures.

Mastectomy remains a valid surgical alternative in selected cases and is usually associated with immediate reconstructive procedures.

New surgical procedures called “conservative mastectomies” are emerging as techniques that combine oncological safety and cosmesis by entirely removing the breast parenchyma sparing the breast skin and nipple-areola complex (NAC).

Staging of the axilla has also gradually evolved toward less aggressive approaches with the adoption of sentinel node biopsy and new therapeutic strategies are emerging in patients with a pathological positivity in sentinel lymph node biopsy.

The present work will highlight the new surgical treatment options increasingly efficacy and respectful of breast cancer patients.

Breast conservation therapy and “oncoplastic” surgery

Breast-conserving surgery (BCS) implies complete removal of the breast tumor with appropriate margins of surrounding healthy tissue performed in a cosmetically acceptable manner. BCS with adjuvant radiotherapy is considered today the gold standard approach for patients with early stage breast cancer. Six prospective trials have shown no significant differences in overall survival rates when comparing BCS plus breast irradiation with mastectomy for early stage breast cancers (2–4).

The choice of BCS versus mastectomy is made taking into account tumor characteristics such as extensive mammographic calcifications, multicentricity, ability to obtain clear surgical margins, tumor size with respect to breast size, as well as for radiotherapy. Patient preferences are also a critical determinant of surgical choice.

For patients who are interested in breast conservation but have a large tumor to breast size ratio, preoperative chemotherapy can be considered to achieve preoperative tumor downsizing. Many trials have shown that patients with locally advanced tumors may become eligible for breast-conserving surgery after tumor downsizing with preoperative chemotherapy, with acceptable rates of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence.

The long-term success of BCS can be measured by two end points: the rate of local control and the cosmetic appearance of the preserved breast. When performing BCS, it may occasionally be difficult for the surgeon to adequately meet both of these end points, particularly when attempting to remove larger lesions or in case of small breasts.

In order to optimize local control, it is mandatory to ensure negative surgical margins. The surgical margin status is considered the strongest predictor for local failure with an increased local recurrence rate in cases with positive margins (defined as tumor cells at the cut edge of the surgical specimen). Positive surgical margins are usually considered an indication for re-excision while the impact of ‘close’ margins (tumor at less than 2mm from the surgical margin) remains controversial. It is generally agreed that best efforts should be made to achieve widely negative margins at the time of initial surgery and that the magnitudine of parenchymal excision should be adeguate to limit the need of re-excision for close or positive margins (5).

The Society of Surgical Oncology (SSO) and the American Society for Radiation Oncology (ASTRO) published evidence-based clinical practice guidelines on surgical margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stage I and II invasive breast cancer in 2014. According to this guideline, the use of no ink on tumor (ie, no cancer cells adjacent to any inked edge/surface of specimen) as the standard for an adequate margin in invasive cancer in the era of multidisciplinary therapy is associated with low rates of ipsilateral breast tumor recurrence and has the potential to decrease re-excision rates, improve cosmetic outcomes, and decrease health care costs (6).

Cosmetic outcome is also directly correlated to the magnitude of parenchymal excision. When larger volumes of tissue are removed, the risk of an unpleasant cosmetic result increases, particularly for cancers located in the central, medial or lower pole of the breast.

In an attempt to optimize the balance between the risk of local recurrence and the cosmetic outcome in BCS, new surgical procedures that combine the principles of surgical oncology and plastic surgery have been introduced in recent years. These new techniques, called “oncoplastic” techniques, may allow removal of larger amounts of breast tissue with safer margins while limiting the risk of a poor cosmetic outcome (7–13). Oncoplastic procedures are less technically demanding and time consuming than major reconstructive operations and surgeons experienced in routine breast surgery can easily incorporate them in their practice with a relatively short learning curve. These procedures are usually performed in a single surgical access, and the patient leaves the operating room without major residual asymmetry or deformity.

The oncoplastic surgery may be classified in two fundamentally different approaches according to the reconstruction techniques following BCS that have been established (10, 11, 13–15) (Tab. 1):

Table 1.

TECHNIQUES CURRENTLY USED FOR THE RECONSTRUCTION OF THE BCS DEFECT.

The techniques that are currently used for the reconstruction of the BCS defect are based on two different concepts:

|

-

Firstly, volume displacement techniques, when the resection defect is reconstructed using one of a range of local glandular or dermoglandular flaps within the breast, which are mobilised and advanced into the defect. This approach leads to a loss in breast volume, and contralateral surgery is usually required to restore symmetry. The options include adjacent (or local) tissue transfer (or rearrangement) and mammoplasty techniques.

Adjacent (or local) tissue transfer (or rearrangement): is perhaps the most common method by which the partial mastectomy defect is reconstructed. This is because these techniques rarely require a two-team approach as the ablative surgeon will apply the principles and techniques to close these defects. Although several surgeons have described various procedures, it is generally accepted that adjacent tissue rearrangement techniques includes accurate decision of skin incision, skin undermining, NAC undermining, glandular reapproximation and deepithelialization and NAC repositioning. An indirect incision along the areola border is preferable; if a direct incision over the tumor is chosen the general principle is to follow Kraissl’s lines of tension to limit visible scaring. An extensive subcutaneous undermining is one of the key factors in adjacent tissue rearrangement techniques; it follows the mastectomy plane and extends anywhere from one-fourth to two-thirds of the surface area of the breast envelope; skin undermining facilitates both tumor resection and glandular redistribution after removal of the tumor; NAC undermining avoid NAC deviation towards the excision area; glandular mobilization and redistribution allow creation of glandular flaps that are used to close the defect without creating a contour abnormality.

A number of conventional mammaplasty techniques have been adapted to allow reconstruction of resection defects with parenchymal flaps using a variety of different approaches. Typically, one of two approaches can be used: the superior pedicle approach or the inferior pedicle approach. The superior pedicle approach enables wide resection of tumors located in the lower quadrants of the breast, where extensive volume loss will often lead to the very unsightly ‘bird’s beak’ deformity. The inferior pedicle approach enables reconstruction of resection defects in the upper pole of the breast (Fig. 1). A range of other approaches have recently been described, which are adaptations of the superior and inferior pedicle approaches.

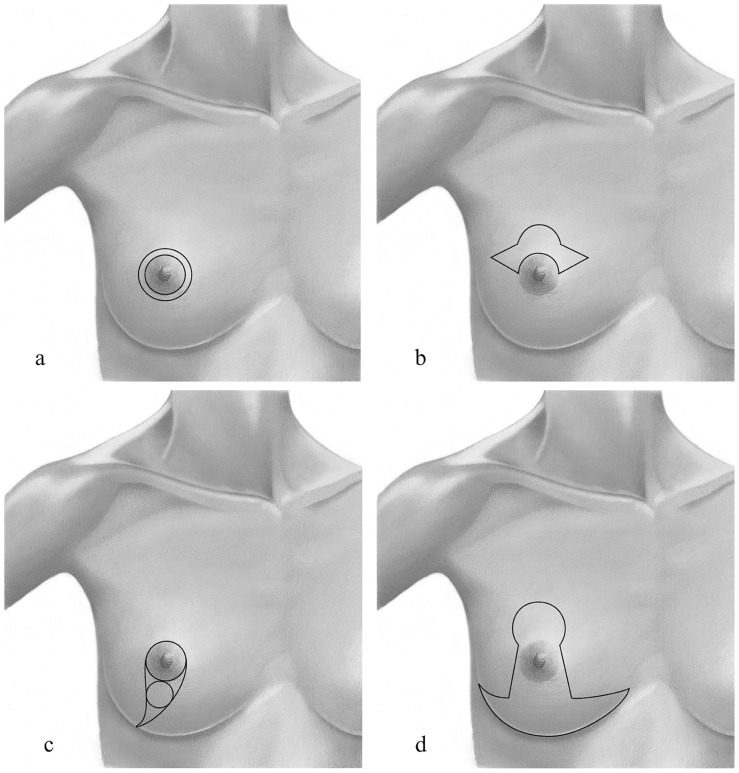

Other established techniques, such as the “Grisotti” technique, the ‘round block’ and “batwing” approach, can be adapted to enable resection of tumors in particular clinical situations (Fig. 2)

Secondly, volume replacement techniques, when the resection defect is reconstructed by replacing the volume of tissue removed with a similar volume of autologous tissue from an extramammary site. The options include musculocutaneous flaps and perforator flaps that can be transferred on a vascularized pedicle or as a free tissue transfer. The most commonly used flap for immediate reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect has been the latissimus dorsi musculocutaneous flap. This flap has been effectively used for deformities of the superior, lateral and inferior aspects of the breasts. In general, a two team approach is needed for this operation owing to the technical aspects in designing, elevating, and mobilizing the flap.

Fig. 1.

Oncoplastic technique of reduction mammaplasty: postoperative view at 7 months.

Fig. 2.

Skin incisions in conservative oncoplastic surgery: a) in the donut mastopexy, two concentric circles of different diameter are designed around the nipple; b) in the batwing mastopexy, two half-circle are designed and connected with angled wings on each side of the areola; c) in the Grisotti procedure, two circles are drawn, one along the borders of the areola, the other below the areola and lines from the medial and lateral sides of the areolar circle are connected down and laterally on the inframammary fold; d) in the reduction mammaplasty, a key-hole pattern incision may be used.

Total and “conservative” mastectomy

When a breast conserving approach cannot guarantee adequate local control and good cosmetic results, total mastectomy should be selected. Common indications to mastectomy include extensive or multicentric disease, inability to obtain clear surgical margins with BCS, large tumor size with respect to the breast size, as well as cases with contraindications for radiotherapy as well as patient preference (15–31). Recent progress in understanding the genetic basis of breast cancer has increased interest in prophylactic mastectomy as a method of preventing hereditary breast cancer.

Various surgical techniques can be adopted when planning a total mastectomy:

Modified radical mastectomy: this technique involves complete removal of the breast with skin and nipple-areola complex, preserving the pectoralis major and minor muscles. It is indicated when the tumor involves the skin or is very close to it and in cases for which prosthetic breast reconstruction is not considered.

-

Conservative mastectomies: new surgical procedures called “conservative mastectomies” (skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomy) are emerging as techniques that combine oncological safety and cosmesis. The conservative mastecomies incorporates the oncological advantage of the total glandular excision, with the satisfactory aesthetic result, offered by the conservation of the skin envelope and the nipple areola complex.

- Skin-sparing mastectomy: this technique preserves the natural skin envelope of the breast while removing the entire glandular tissue and nipple-areola complex. Studies have shown that LR rates for skin-sparing mastectomies are comparable to those of non–skin-sparing mastectomies in patients with non invasive and early stage breast cancer. This technique is also well-suited for those patients at high risk for developing breast cancer who opt for a prophylactic mastectomy. Smoking, previous radiation, diabetes, and obesity can increase the risk of necrosis and infection of the skin. Skin-sparing mastectomy combined with immediate reconstruction can provide excellent cosmetic results (15–17).

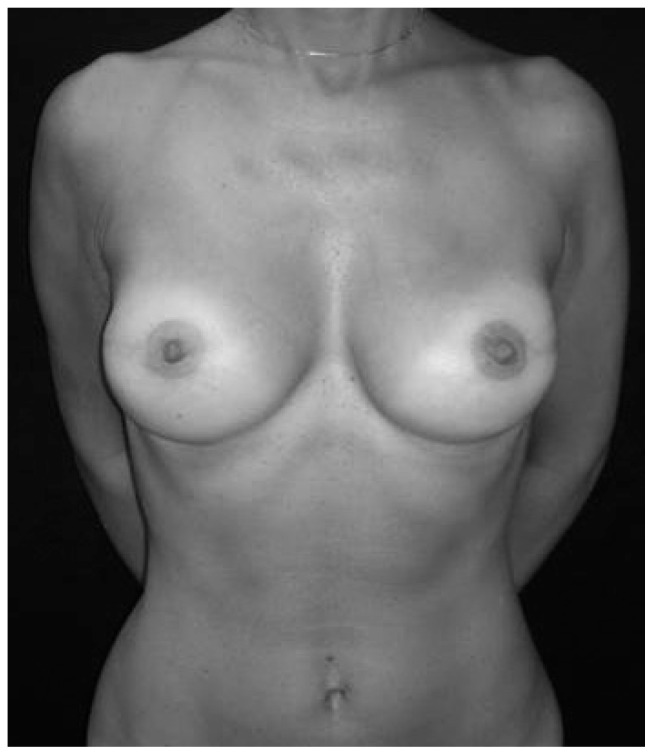

- Nipple–sparing mastectomy: this technique involves removal of breast tissue with preservation of the nipple-areola complex (Fig. 3). It is not indicated in cases with large cancers or with tumors close to the nipple or centrally located, or those with clinical evidence of NAC involvement. Women with severe ptosis are poor candidates because nipple displacement is a problem. It is indicated in patients undergoing prophylactic surgery. Frozen sections on the retroareolar tissue need to be performed intraoperatively to rule out evidence of tumor cells. If cancer cells are detected, the NAC will have to be removed. Possible sequelae of the procedure may be partial or total necrosis of the NAC and loss of nipple sensation. More extensive studies with long-term follow-up are necessary to fully evaluate the optimal technique and its long-term effects (18–26).

Fig. 3.

A bilateral nipple-sparing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction with a definitive anatomical prosthesis.

Sentinel node biopsy

Axillary lymph node status still represents a critical point when planning adjuvant treatments, as well as a strong predictor of local disease free and overall survival. Unfortunately, there is still no preoperative diagnostic tool that can reliably assess whether cancer cells have spread to the axillary lymphatic basins, so that this remains a great unanswered question until after the surgical procedure is completed.

Axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), which has been the standard approach for evaluating lymph node status throughout the last century, has been called into question over the last 15 years due to its invasiveness and potential morbidity. As a result, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), a minimally invasive technique, was developed to avoid lymph node dissection in patients who have a low probability of axillary metastasis (32–48). The sentinel node is the first lymph node which receives lymph from the anatomic site of the primary breast tumour. The rationale for the adoption of sentinel node biopsy is that, due to the linear involvement of axillary nodes by tumour cells, the histological characteristics of this first lymph node would be representative of all the other axillary nodes. With this procedure, an axillary lymph node dissection is therefore performed only in case of pathologic evidence of metastatic disease in the SLN, thus avoiding unnecessary and potentially harmful surgical procedures. The technique of mapping the sentinel node in breast cancer patients was developed in the early 1990s and, since then, has been refined and validated.

Today, sentinel node biopsy is considered the gold standard for nodal staging in patients with early breast cancer. The technique is performed intraoperatively with periareolar injection of vital blue dye, technetium-labeled sulfur colloid, or a combination of the two; any node that has taken up the dye or tracer is removed and, generally, sent for intraoperative examination to rule out the presence of metastasis.

If the sentinel lymph node biopsy is positive for metastasis, then axillary lymph node dissection is warranted; if it is negative, no additional axillary surgery is needed. If this mapping procedure fails to clearly identify a sentinel node, then a complete axillary lymph node dissection is performed. Reasons for failed mapping include technical issues as well as anatomic ones. Performing sentinel lymph node biopsies clearly involves a learning curve, and the sensitivity and specificity of these biopsies do vary among surgeons, correlating with the surgeons’ technical experience. Lymphatic mapping and SLN biopsy is experiencing a wide diffusion and many technical aspects of the procedure are evolving.

For patients with clinically node-negative early breast cancers, SLNB is confirmed as the gold standard for axillar staging in guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) (39), the International Expert Consensus Panel on the Primary Therapy of Early Breast Cancer (41), and others (42, 43). These observations reduced ALND indications only to women who have positive nodes confirmed preoperatively by methods such as ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration or after SLNB even if new therapeutic strategies are emerging in patients with a pathological positivity in SLNB.

Management of sentinel lymph node metastases and current controversies

SLN metastases are categorized as isolated tumor cells, micrometastases, or macrometastases, depending upon the size of the largest tumor deposit in the sentinel node and leading to different approaches in axillar treatment.

Management of positivity to isolated tumor cells (small clusters of cells not greater than 0.2 mm, or non-confluent or nearly confluent clusters of cells not exceeding 200 cells in a single histologic lymph node cross section) are considered prognostically similar to node negative. As a matter of fact, they are designated as pN0 (i+) and do not constitute an indication for further axillary treatment (even surgery, radiation treatment, or adjuvant systemic therapy).

Nevertheless, SLNB positivity to micrometastases (tumor foci >0.2 mm and no greater than 2.0 mm) and macrometastases (tumor foci >2 mm) represented a matter of debate and deep controversies in recent versions of evidence based guidelines.

The SLN is the sole tumor-bearing node in up to 60 percent of cases overall, and in almost 90 percent of patients who harbor only micrometastatic disease. These observations have led to speculation that completion ALND may not be necessary in selected patients with a positive SLNB in less than three nodes because the need for systemic therapy is established (48–53) and the risk of an axillary recurrence appears to be low (54–57).

The International Breast Cancer Study Group trial 23-01 (IBCSG 23-01) randomized patients with SLN micrometastases (<2 mm) and primary tumors <5 cm in size to either completion ALND or no additional axillary surgery (58) evidencing no significant difference in disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) at a median follow-up of 49 months.

In breast cancer patients with T1 e T2 tumours, no palpable adenopathy and 1/2 sentinel lymph nodes containing macro- or micrometastases, the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group (ACOSOG) Z0011 trial compared observation only to complete axillary lymph node dissection following sentinel node biopsy (59). No significant differences in recurrence rates, DFS and OS were noted between the two groups at a median follow-up of 6.3 years.

Based upon the apparent lack of regional benefit and low risk of events in these trial, completion ALND may not be necessary for all women with T1-2 tumors that are clinically node negative, with less than three positive SLNs, who will be treated with whole breast radiation and systemic therapy, particularly in women with estrogen receptor positive tumors.

Importantly however, several criticism on major study bias on these two trials may configure that they are not sufficient to provide strong recommendations that could uniformly change the actual management of axillary nodes. The effect of controversial interpretation of these studies, is that there is a lack of uniformity in axillar behavior in presence of SLNB positivity.

The 2014 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guidelines and 2015 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines reflect the most conservative treatment, recommending completion ALND only for patients with more than 2 positive lymph nodes while most women who meet precise criteria (T1-2 tumor, 1–2 positive lymph-nodes, absence of previous neoadjuvant therapy and for which is planned breast conserving surgery with whole breast irradiation) should not undergo ALND (39, 43).

The future behaviour on axillary treatment seems to aim to consider SLNB as the only surgical manoeuvre for axillary staging in patients undergoing conservative breast surgery for early stage neoplasms for which is planned adjuvant therapy, but presently, further evidence and longer follow-up results must be provided in order to clearly delineate an uniformity in different treatment guidelines.

References

- 1.GLOBOCAN. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012;2012 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, et al. Twenty-year follow-up a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and Lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1233–41. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, et al. Twenty-year followup of a randomized study comparing breast conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1227–322. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Franceschini G, Terribile D, Fabbri C, et al. Progresses in the-treatment of early breast cancer. A mini-review. Ann Ital Chir. 2008;79(1):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanguinetti A, Lucchini R, Santoprete S, et al. Surgical margins in breast-conserving therapy. Current trends and future prospects. Ann Ital Chir. 2013;84(6):595–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buchholz TA, Somerfield MR, Griggs JJ, et al. Margins for breast-conserving surgery with whole-breast irradiation in stage I and II invasive breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology endorsement of the Society of Surgical Oncology/American Society for Radiation Oncology consensus guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1502–06. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson B, Masetti R, Silverstein M. Oncoplastic approaches topartial mastectomy: An overview of volume-displacement techniques. The Lancet Oncology. 2005;6:145–57. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)01765-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silverstein MJ. How I do it: Oncoplastic breast-conservation surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17(Suppl 3):242–44. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1240-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spear SL. Oncoplastic surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(3):993–94. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b17ab3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nahabedian MY. Oncoplastic Surgery of the Breast. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Franceschini G, Terribile D, Magno S, et al. Update ononcoplastic breast surgery. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(11):1530–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franceschini G, Magno S, Fabbri C, et al. Conservative and radical oncoplastic approches in the surgical treatment of breast cancer. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2008;12(6):387–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanaka S, Sato N, Fujioka H, et al. Breast conserving surgery using volume replacement with oxidized regenerated cellulose: A cosmetic outcome analysis. Breast J. 2014;20(2):154–58. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franceschini G, Visconti G, Terribile D, et al. The role of oxidized regenerate cellulose to prevent cosmetic defects in oncoplastic breast surgery. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16(7):966–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spear SL. Surgery of the Breast Principles and Art. Third Edition. New York: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bland KI, Klimberg V, editors. Breast Surgery. New York: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patani N, Mokbel K. Oncological and aesthetic considerations of skin-sparing mastectomy. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;111(3):391–403. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9801-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta A, Borgen PI. Total Skin Sparing (Nipple Sparing) Mastectomy: What is the Evidence? Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2010;19(3):555–66. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2010.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maxwell GP, Storm-Dickerson T, Whitworth P, et al. Advances in nipple-sparing mastectomy: Oncological safety and incision selection. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31(3):310–19. doi: 10.1177/1090820X11398111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boukerrou M, Dahan Saal J, Laurent T, et al. Nipple sparing mastectomy: An update. Gynecol Obstet Fertil. 2010;38(10):600–06. doi: 10.1016/j.gyobfe.2010.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rusby JE, Smith BL, Gui GP. Nipple-sparing mastectomy. Br J Surg. 2010;97(3):305–16. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Agha-Mohammadi S, De La Cruz C, Hurwitz DJ. Breast reconstruction with alloplastic implants. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94(6):471–78. doi: 10.1002/jso.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Atisha DM, Comizio RC, Telischak KM, et al. Interval inset of TRAM flaps in immediate breast reconstruction: A technical refinement. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;65(6):524–27. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181d9aac7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Granzow JW, Levine J, Chiu Es, et al. Breast reconstruction using perforator flaps. J Surg Oncol. 2006;94:441–54. doi: 10.1002/jso.20481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu LC, Bajaj A, Chang DW, Chevray PM. Comparison of donor-site morbidity of SIEA, DIEP, and muscle-sparing TRAM flaps for breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122(3):702–09. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181823c15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lo Tempio MM, Allen RJ. Breast reconstruction with SGAP and IGAP flaps. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126(2):393–401. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181de236a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franceschini G, Terribile D, Fabbri C, et al. Management of locally advanced breast cancer. Mini-review. Minerva Chir. 2007;62(4):249–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nardone L, Valentini V, Marino L, et al. A feasibility study of neo-adjuvant low-dose fractionated radiotherapy with two different concurrent anthracycline-docetaxel schedules in stage IIA/B-IIIA breast cancer. Tumori. 2012;98(1):79–85. doi: 10.1177/030089161209800110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Franceschini G, Terribile D, Magno S, et al. Current controversies in the treatment of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast. Ann Ital Chir. 2008;79(3):151–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Franceschini G, Terribile D, Magno S, et al. Update in the treatment of locally advanced breast cancer: A multidisciplinary approach. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2007;11(5):283–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Salgarello M, Visconti G, Barone-Adesi L, et al. Inverted-T skin-reducing mastectomy with immediate implant reconstruction using the submuscular-subfascial pocket. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130(1):31–41. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182547d42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Veronesi U, Zurrida S. Breast conservation: Current results and future perspectives at the European Institute of Oncology. Int J Cancer. 2007;120(7):1381–386. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Viale G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary dissection in breast cancer: Results in a large series. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91:368–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.4.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kelley LM, Holmes DR. Tracer agents for the detection of sentinel lymph nodes in breast cancer: current concerns and directions for the future. J Surg Oncol. 2011 Jul 1;104(1):91–6. doi: 10.1002/jso.21791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Petronella P, Scorzelli M, Benevento R, et al. The sentinel lymph node: a suitable technique in breast cancer treatment? Ann Ital Chir. 2012;83(2):119–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mabry H, Giuliano AE. Sentinel node mapping for breast cancer: progress to date and prospects for the future. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2007;16:55. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Straver ME, Meijnen P, van Tienhoven G, et al. Sentinel node identification rate and nodal involvement in the EORTC 10981–22023 AMAROS trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1854. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-0945-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Veronesi U, Viale G, Paganelli G, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: Ten-year results of a randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2010;251:595. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181c0e92a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyman GH, Temin S, Edge SB, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for patients with early-stage breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(13):1365–83. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Picciocchi A, Terribile D, Franceschini G. Axillary lymphadenectomy. Ann Ital Chir. 1999;70(3):349–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz GF, Giuliano AE, Veronesi U Consensus Conference Committee. Proceedings of the consensus conference on the role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in carcinoma of the breast, April 19–22, 2001, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Cancer. 2002;94:2542. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cantin J, Scarth H, Levine M, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the care and treatment of breast cancer: 13. Sentinel lymph node biopsy. CMAJ. 2001;165:66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) NCCN Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. 2015. http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/f_guidelines.asp.

- 44.Naik AM, Fey J, Gemignani M, et al. The risk of axillary relapse after sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer is comparable with that of axillary lymph node dissection: A follow-up study of 4008 procedures. Ann Surg. 2004;240:62. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137130.23530.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Swenson KK, Mahipal A, Nissen MJ, et al. Axillary disease recurrence after sentinel lymph node dissection for breast carcinoma. Cancer. 2005;104:1834. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giuliano AE, Haigh PI, Brennan MB, et al. Prospective observational study of sentinel lymphadenectomy without further axillary dissection in patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.13.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roumen RM, Kuijt GP, Liem IH, van Beek MW. Treatment of 100 patients with sentinel node-negative breast cancer without further axillary dissection. Br J Surg. 2001;88:1639. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krag D, Weaver D, Ashikaga T, et al. The sentinel node in breast cancer. A multicenter validation study. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:941. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199810013391401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giuliano AE, Jones RC, Brennan M, Statman R. Sentinel lymphadenectomy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2345. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Veronesi U, Paganelli G, Galimberti V, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy to avoid axillary dissection in breast cancer with clinically negative lymph-nodes. Lancet. 1997;349:1864. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albertini JJ, Lyman GH, Cox C, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in the patient with breast cancer. JAMA. 1996;276:1818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Borgstein PJ, Pijpers R, Comans EF, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in breast cancer: Guidelines and pitfalls of lymphoscintigraphy and gamma probe detection. J Am Coll Surg. 1998;186:275. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(98)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Turner RR, Chu KU, Qi K, et al. Pathologic features associated with nonsentinel lymph node metastases in patients with metastatic breast carcinoma in a sentinel lymph node. Cancer. 2000;89:574. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<574::aid-cncr12>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Naik AM, Fey J, Gemignani M, et al. The risk of axillary relapse after sentinel lymph node biopsy for breast cancer is comparable with that of axillary lymph node dissection: a follow-up study of 4008 procedures. Ann Surg. 2004;240:462. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000137130.23530.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hwang RF, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, Yi M, et al. Low locoregional failure rates in selected breast cancer patients with tumor-positive sentinel lymph nodes who do not undergo completion axillary dissection. Cancer. 2007;110:723. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fant JS, Grant MD, Knox SM, et al. Preliminary outcome analysis in patients with breast cancer and a positive sentinel lymph node who declined axillary dissection. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10:126. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jeruss JS, Winchester DJ, Sener SF, et al. Axillary recurrence after sentinel node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2005;12:34. doi: 10.1007/s10434-004-1164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Galimberti V, Cole BF, Zurrida S, et al. Axillary dissection versus no axillary dissection in patients with sentinel-node micrometastases (IBCSG 23-01): A phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(4):297–305. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70035-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Giuliano AE, Hunt KK, Ballman KV, et al. Axillary dissection vs no axillary dissection in women with invasive breast cancer andsentinel node metastasis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2011;305(6):569–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]