Abstract

It has been over a century since Perls described the first case of choroidal metastasis. For the next six decades only 230 cases were described in the literature. Today, however, ocular metastasis is recognized as the most common intraocular malignancy. Thanks to recent advances in treatment options for metastatic disease, patients are living longer, and choroidal metastases will become an increasingly important issue for oncologists and ophthalmologists alike. We summarize the current knowledge of choroidal metastases and examine their emerging systemic and local therapies. Targeted therapies for metastatic lung, breast, and colon cancer—the most common causes of choroidal metastases—are reviewed in detail with the goal of identifying the most effective treatment strategies.

Keywords: choroidal metastases, ocular metastases, targeted therapy

I. Introduction

Based on Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results data from 2005–2007, 41% of men and women have a lifetime risk of cancer. In January 2007, over 11 million men and women alive in the United States had a history of cancer.1 Ocular metastasis was first reported in 187250 and, for over a century, has been considered rare. Because of the improved life expectancy of patients with metastatic disease, however, uveal metastases are being diagnosed more frequently and are now known to be the most common intraocular malignancies, found in up to 8% of patients with cancer at autopsy.7 Evolving systemic and local treatments have expanded the options for treating metastatic lesions. We discuss these and will also present a case report that illustrates regression of choroidal metastasis with systemic chemotherapy and how choroidal metastases can mirror the systemic response to chemotherapy.

II. Case Report

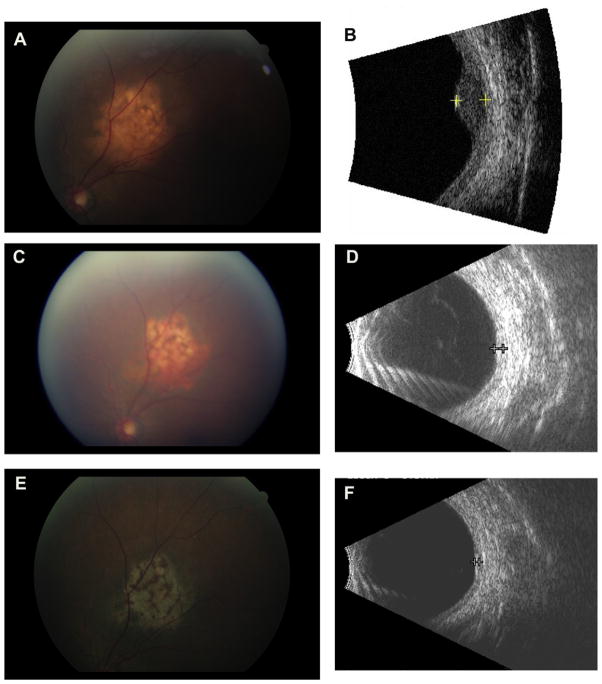

A 63-year-old Taiwanese woman presented with a 3-month history of blurred vision, flashes, and floaters in the left eye. Visual acuity measured 20/20 in the right eye and 20/60 in the left eye. On dilated fundus examination she was found to have a leopard-spotted, orange choroidal lesion superotemporal to the optic disc with subretinal fluid extending through the macula (Fig. 1A). Echography revealed a dome-shaped lesion with irregular reflectivity, intralesional vascularity, and a maximal elevation of 2.9 mm (Fig. 1B). The clinical and echographic findings were consistent with choroidal metastasis.

Fig. 1.

A: Initial presentation of a choroidal metastasis with orange, leopard-spotted lesion that was associated with subretinal fluid. B: Initial echographic appearance of a dome-shaped lesion with irregular reflectivity, and a maximal elevation of 2.9 mm. C: Choroidal metastasis after response from systemic therapy. D: Echography shows reduction in thickness to 1.0 mm. E: Choroidal metastases appears as a flat scar. F: Echography shows minimal thickening (<1.0 mm).

The patient was referred to the oncology clinic for a complete evaluation. A positron emission tomography scan showed hypermetabolic foci in the thyroid, lungs, cervical and pelvic lymph nodes, ribs, and vertebral bodies. Immunohistochemistry stains of lung and mandibular biopsies were positive for thyroid transcription factor-1 and surfactant protein-A and negative for thyroglobulin, findings consistent with a primary lung papillary carcinoma. Testing for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) mutations revealed a mutation at L861Q on exon 21, predicting a beneficial response to the tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib.14,48 With a diagnosis of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer and the EGFR mutation identified, the patient began treatment with erlotinib.

Two months into treatment with erlotinib, the patient’s visual acuity had improved to 20/25 in the left eye. The choroidal lesion height measured <2 mm and the macula was flat. Repeat orbital ultrasound showed that the lesion thickness was 1.0 mm, approximately one-third of its original size (Fig. 1D).

After 7 months of treatment, the choroidal lesion had increased in height from 1.0 mm to 1.7 mm, and both the lung and brain metastases had progressed. The patient received 3,500 cGy of total brain radiation for intracranial metastases. After a further drop in visual acuity to 20/80 and reaccumulation of subretinal fluid, she was tried on various other systemic therapies and was eventually changed to single-agent docetaxel.

Following two cycles of docetaxel, visual acuity improved to 20/40, the lesion height decreased to 1.0 mm, and there was no evidence of subretinal fluid. Radiologic studies showed interval improvement in the lymph node, lung, and bone metastases and stability of brain metastases. Four months after the completion of 10 cycles of docetaxel, and 2 years following her original diagnosis, the patient’s metastatic disease and ocular examination are both stable (Fig. 1C).

III. Systemic Therapies

Although usually associated with other systemic metastases, choroidal metastases may be the first presentation of an unknown primary or the first sign of relapse of a known primary cancer. If systemic therapy or reinduction chemotherapy has not been attempted, it is generally the first step for treating metastatic disease. Because the choroid is external to the blood ocular barrier, systemic medications diffuse freely into the choroid via the fenestrated endothelium of the choriocapillaris. Effective control of choroidal metastases has been observed with systemic medications alone (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Evidence for Regression of Choroidal Metastatic Lesions with Systemic Therapy

| Study | Primary Cancer | No. of Subjects | No of Eyes | Chemotherapy | Local Therapies | Time to Lesion Regression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letson33 | Breast | 15 | 17 | various regimens | In 8 of 15 patients | - |

| Manquez40 | Breast | 17 | - | anastrozole, letrozole, exemestane | None | 10 showed lesion regression, 7 did not |

| Brinkley8 | Breast | 1 | 1 | 5-FU, methotrexate, cytoxan, prednisone, vincristine | None | 2 months |

| Logani38 | Breast | 1 | 1 | cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, fluorouracil, and tamoxifen, | None | 5 months |

| Munzone47 | Breast | 1 | 1 | trastuzumab, paclitaxel, later vinorelbine | None | 1–2 months |

| Wong69 | Breast | 1 | 1 | trastuzumab, vinorelbine | None | 1 month |

| Kosmas31 | Breast | 1 | 1 | mitoxantrone, docetaxel | None | Up to 4.5 months |

| George17 | Non-small cell lung | 1 | 1 | carboplatin, gemcitabine, bevacizumab | None | - |

| Battikh4 | Pulmonary adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1 | gemcitabine, cisplatin | None | - |

| Morris45 | Esophageal adenocarcinoma | 1 | 1 | cisplatin, irinotecan | None | 1 week |

| Samuel56 | Esophageal adenocarcioma | 1 | 1 | carboplatin, 5-FU | None | 1 month |

| Biswal6 | Nasopharyngeal | 1 | 1 | cisplatin, 5-FU | None | 2 months |

5-FU = 5-fluorouracil.

Over the past decade, the development of new biologic agents has dramatically changed cancer therapy. During the clinical development of anti-cancer drugs, clinicians repeatedly encountered difficulties with acute and long-term toxicities of chemotherapies that affected virtually every organ of the body. Cytotoxic effects on the rapidly dividing bone marrow cells and cells of the gastrointestinal mucosa almost always led to diarrhea, stomatitis, and myelosuppression. Long-term effects on the lungs, heart, and reproductive organs were also formidable barriers. The hope was that there might be a “magic bullet” that would target solid tumors without associated toxicities.10,24 In the early 1980s, important progress in molecular and genetic research revealed new signaling pathways that regulate cell proliferation and survival. These pathways are markedly altered in cancer cells, leading to unchecked proliferation. As a result, there has been significant scientific interest in developing treatments to repair these molecular defects. Thus began a generation of targeted cancer therapy directed at specific molecular targets.

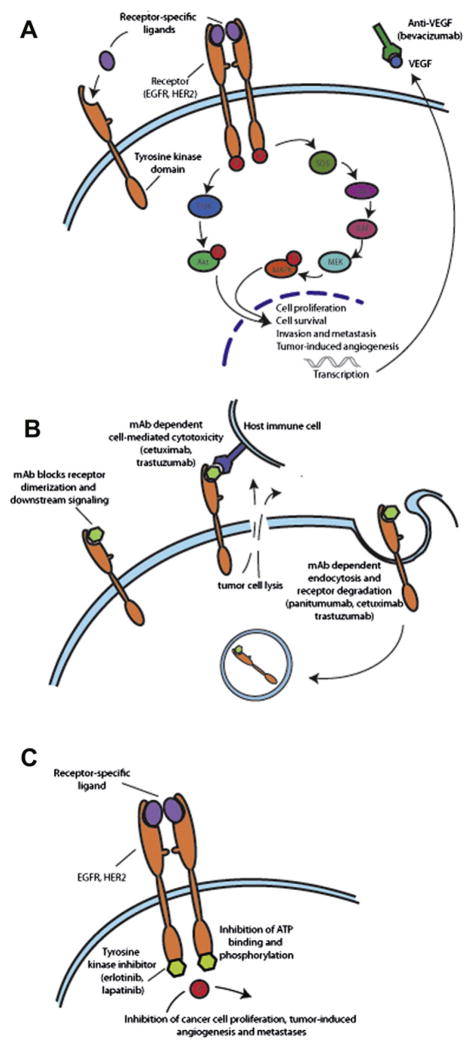

Small molecules and monoclonal antibodies have been developed to target key factors in tumor proliferation—including growth factors, signaling molecules, cell-cycle proteins, and modulators of apoptosis and angiogenesis. Monoclonal antibodies bind with high affinity and specificity to their receptor targets (e.g., vascular endothelial and epidermal growth factor receptor), causing inhibition of downstream effects (Fig. 2B). Köhler and Milstein30 engineered the first monoclonal mouse antibodies in 1975 using a technique of somatic cell hybridization.30 Later advances led to the development of chimeric and humanized anti-mouse antibodies, which are partly constructed from human sources and confer improved efficacy and reduced immunogenicity. Small molecules such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are less specific than monoclonal antibodies, and some have the added advantage of simultaneously inhibiting multiple targets. Protein tyrosine kinases catalyze the transfer of phosphate from ATP to tyrosine residues in polypeptides. Tyrosine kinases can be classified as receptor protein kinases, which are membrane-spanning cell surface proteins, and nonreceptor protein kinases. For receptor kinases, TKIs competitively bind to the ATP binding site of the intracellular tyrosine kinase catalytic domain and block receptor autophosphorylation and downstream signaling (Fig. 2C). Some TKIs may also inhibit downstream cell receptors or signal transduction pathway proteins.

Fig. 2.

A: The EGFR-dependent signaling pathway. The receptor-specific ligand binds to the extracellular domain of the single-chain EGFR or EGFR-related receptors such as HER2. Then, the ligand-bound EGFR forms activated homodimers or heterodimers leading to ATP-dependent phosphorylation of specific tyrosine residues on the in-tracellular domain. This phosphorylation triggers downstream signaling to the cytoplasm and then nucleus. The two major pathways activated by EGFR are (1) the RAS-RAF-MEK-MAPK pathway that regulates gene transcription, cell-cycle progression from the G1 to the S phase, and cell proliferation, and (2) the PI3K-Akt pathway that activates a cascade of anti-apoptotic and prosurvival signals. B: Monoclonal antibodies bind to the extracellular domain of EGFR or EGFR-like receptor and block ligand binding, receptor activation, and downstream signaling. C: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors compete with ATP binding sites on the intracellular tyrosine kinase catalytic domain blocking phosphorylation and subsequent downstream effects. mAb = monoclonal antibody; EGFR = epidermal growth factor receptor; HER2 =human epidermal growth factor receptor 2; MAPK = mitogen-activated protein kinase; VEGF = vascular endothelial growth factor; PI3K = phosphatidylinositol 3,45-kinase.

When compared with traditional chemotherapies, the side-effect profiles of target-specific therapy are generally more favorable and predictable. Conventional chemotherapy interferes with cell division and does not discriminate effectively between rapidly dividing tumor cells and normal cells, leading to toxic side effects such as myelosupression, hepatotoxicity, and nephrotoxicity. In contrast, targeted therapies are aimed at distinct molecular pathways involved in tumor growth, proliferation, and metastases. Targeted therapies have more specificity towards tumor cells than normal cells and can provide a broader therapeutic window with less toxicity. A particular side effect of monoclonal antibodies relates to a hypersensitivity from the murine component, and is characterized as a flu-like syndrome in 40% of patients during the initial drug infusion. Fully humanized monoclonal antibodies, such as panitumumab, avoid this problem. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors generally inhibit more targets than monoclonal antibodies, which may be an advantage for efficacy but can be a disadvantage in that they have a broader side-effect profile.67 Each targeted therapy also has side effects related to the modulation of specific molecular targets in normal tissues; however, most of these adverse effects are manageable and reversible upon discontinuation of the drug.

Targeted systemic therapy provides a new approach for cancer therapy while avoiding some of the toxicities that limit traditional chemotherapy. Specific targets for cancer therapy will be discussed in the context of their success in controlling systemic disease and with inducing choroidal metastases regression.

A. NON-SMALL CELL LUNG CANCER

Biologic agents such as erlotinib and bevacizumab are new approaches to treatment of non-small cell lung cancers (NSCLCs). Erlotinib is a tyrosine kinase inhibitor of EGFR that has led to favorable responses, as seen in our patient who has the somatic gain-of-function mutation around the ATP binding pocket of the EGFR protein kinase domain.39 EGFR plays an important role in cancer cell proliferation, angiogenic growth factor production, and cancer cell invasion12,16 (Fig. 2A). Similarly, treatment with bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody directed at vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), has shown a measurable response in choroidal metastases when used with other agents.17 Bevacizumab binds to VEGF and blocks ligand binding to VEGFR2 and subsequent tyrosine kinase signaling. Erlotinib is relatively well tolerated with dose-dependent side effects of diarrhea, acneiform rashes, and folliculitis. Bevacizumab is less commonly used alone for NSCLC, but its side effects are attributed to decreased renewal capacity of endothelial cells in response to trauma and increased tissue factor activation after exposure to subendothelial collagen.18 As a result, patients may experience delayed wound healing, increased risk of bleeding, and thromboembolic events.

B. BREAST CANCER

The majority of breast cancers in postmenopausal women express estrogen or progesterone receptors, and, as a result, endocrine therapy with tamoxifen and aromatase inhibitors (anastrozole, letrozole, and exemestane) plays an important role in treatment.38 Manquez etal40 found choroidal metastases regression with aromatase inhibitors in 10 out of 17 patients with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer over a mean follow-up of 20 months (Table 1). The main side effects of endocrine therapy are hot flashes, night sweats, and depression.9 Women with an intact uterus are also at risk of tamoxifen-associated endometrial cancer given tamoxifen’s partial estrogen agonist effects on the endometrium. With aromatase inhibitors bone loss secondary to estrogen deficiency can also be seen, although in the study by Manquez et al40 no toxicity or intolerance to aromatase inhibitors was observed over a mean follow-up of 20 months. The receptor tyrosine kinase ERBB2, also known as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), has also become an important target because it is overex-pressed in up to 20–30% of breast cancer cases. Trastuzumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to the extracellular juxtamembrane domain of HER2 and prevents its activation.23 In two reports trastuzumab in combination with other systemic therapies led to the regression of choroidal metastases within 1–2 months.47,69 Cardiac dysfunction was seen in 3–7% of patients enrolled in clinical trials of trastuzumab alone, but 75% of these patients improved with treatment for congestive heart failure.57

C. COLON CANCER

In colon cancer monoclonal antibodies against the extracellular domain of EGFR and VEGF have also been effective. Currently cetuximab and panitumumab, both monoclonal antibodies that block the extracellular domain of EGFR, have been U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved for EGFR-expressing metastatic colon cancer in combination with fluoropyrimidines, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, orbest supportive care for patients who cannot tolerate first line agents. Panitumumab is a fully human monoclonal antibody specific for the extracellular domain of EGFR. Cetuximab is a mouse/human chimeric IgG1 immunoglobulin that has the added benefit of antibody-dependent cytotoxicity through activation of the host immune response12 (Fig. 2B). Because EGFR is involved in the proliferation, survival, and differentiation of keratinocytes in the skin, cutaneous side effects are common.26 Patients can develop folliculitis, xerosis, or paronychial inflammation, and often require co-management with dermatologists because anti-EGFR therapy may be administered for prolonged periods in patients who respond.51

Bevacizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody to VEGF, is FDA-approved for use in advanced colorectal cancer with any intravenous fluorouracil-containing regimen as initial therapy. Most types of human cancer cells, including colon cancer cells, express VEGF at elevated levels, and the hypoxic state of solid tumors is an important inducer of VEGF. Bevacizumab blocks this pathway and causes modest tumor regression in metastatic colon cancer.55 The side effects of bevacizumab, as mentioned previously, include delayed wound healing, hemorrhage, and thromboembolic events.15,28,67

D. MERITS OF SYSTEMIC CHEMOTHERAPY

In treating choroidal metastases, ophthalmologists have routinely observed patients for lesion regression after reinitiation of systemic chemotherapy. A case report by Brinkley et al in 1980 highlights a patient with choroidal metastases from breast cancer that demonstrated complete lesion regression after treatment with a combination of five chemotherapeutic agents.8 Later in 1982, Letson et al reviewed 15 cases of choroidal metastases from breast carcinoma, eight who were treated with external radiation therapy, six with chemotherapy, and one patient received both.33 In this retrospective study, chemotherapy proved to be equally as effective as radiation therapy based on clinical lesion regression (decrease in tumor size, elevation, pigment clumping, and fluid resorption) and improved visual acuity. Common practice has been to wait at least 6 weeks to see the effects of systemic therapy on lesion regression.66 If the choroidal lesions enlarge over this observation period, then locally delivered therapy such as plaque brachytherapy and external beam radiation is recommended.59,66 Larger studies on plaque brachytherapy and external beam radiotherapy using this paradigm predated the development of newer, targeted therapy with monoclonal antibodies and small molecule inhibitors that are routinely used in chemotherapy regimens today.35,53,58 Several case reports, including our patient with NSCLC, have shown that with the addition of new biologic agents and hormone therapies, patients may respond within a reasonable time period on systemic therapy alone.40,47,69

Considering the improved tumor control with biologic therapies and newer hormone therapies, an argument can be made for a modification in the treatment approaches for choroidal metastases. Treating with systemic chemotherapy with a longer period of observation might be a better choice in patients who have multiple uveal lesions or peri-papillary lesions not amenable to radiation therapy because of the risk of visually significant radiation retinopathy or papillopathy. Systemic treatment alone may also benefit the patient with very anterior uveal lesions where plaque brachytherapy, external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), radiosurgery, and proton beam therapy can have a higher risk of causing cataract. These patients, who already have a significant disease burden, not only benefit from a simpler treatment regimen, but also avert the risks of periocular and intraocular infections. For choroidal metastases treated with chemotherapy alone, lesion regression is usually observed after a range of 1–4 months, which is comparable to the response rate seen with locally delivered therapy.

Systemic therapy, even with targeted biologic agents, may have significant side effects, particularly in those with low performance status. Side effects are more commonly seen with traditional cytotoxic agents and may limit treatment duration or dosage. Samuel et al characterize a patient with choroidal metastasis with serous detachment from primary esophageal adenocarcinoma.56 The patient experienced a clear response to systemic chemotherapy with carboplatin and 5-fluorouracil, but after 3 months chemotherapy was halted because of generalized weakness, and the lesion recurred, though it was not visually significant.

IV. Local Therapies for Choroidal Metastases

The decision to pursue local therapy for choroidal metastases is multidisciplinary, involving the patient, oncologist, ophthalmologist, and radiation oncologist. Important considerations include patient preference, overall health, location and extent of intraocular lesion, and visual symptoms. Choroidal metastatic lesions responding well to systemic therapies generally do not require direct treatment; in cases where a choroidal metastasis is enlarging during systemic therapy or is the only distant site for metastasis, however, then local therapy to the ocular tissues is recommended.2,11,60 Local therapy can include radiotherapy (external beam, plaque brachytherapy, Gamma knife, and proton beam), intravitreal injection, laser therapy, cryotherapy, or resection. The goal in emerging local therapies is to restore visual function while minimizing ocular toxicity, here defined as collateral damage to other parts of the eye.

A. RADIOTHERAPY

EBRT is a well-established and widely available treatment for uveal metastases that fail to regress despite systemic therapy that was first applied in 1979.64 Lesion regression is seen in 85–93% of patients. Complications from radiotherapy, such as cataracts, exposure keratopathy, iris neovascularization, radiation retinopathy, and radiation papillopathy, will be seen in about 12% of patients over a median of 5.8 months of follow-up. Patients who live longer have a statistically higher probability of developing side effects,53 and as new modalities of treatment prolong life expectancy, the number of ocular complications from radiotherapy is also expected to rise.53 In addition to ocular toxicity, the main disadvantage of EBRT is the need for repeated daily treatments (at least 10 daily fractionated treatments for a total of 30–50 Gy),52–54,68 a time commitment that is significant for a patient with metastatic disease and limited life expectancy. Because of these drawbacks, other radiotherapeutic techniques that promise less ocular toxicity or shorter treatment times have been applied to choroidal metastases. These include plaque brachytherapy, Gamma knife, CyberKnife, and proton beam radiotherapy.

Plaque brachytherapy permits radiation to be delivered directly to the choroidal lesion and has been used successfully for choroidal melanomas and, more recently, for solitary choroidal metastasis. In one retrospective study of 36 patients, lesion regression was noted in 94% of patients at a mean follow-up of 11 months.60 Complications were seen in 8% of patients and included radiation retinopathy, papillopathy, and cataract in anteriorly placed plaques.60 In this study, the overall survival from the time of diagnosis of uveal metastasis was 8 months, thereby limiting the occurrence of late side effects. Visual prognosis was fair, with 19% showing improvement, 39% showing no change, and 42% showing decreased visual acuity. Mean therapeutic radiation dose was 69 Gy to tumor apex and 236 Gy to tumor base, which is less radiation than choroidal melanoma where the mean therapeutic dose is 80–95 Gy at tumor apex and 340–390 Gy at the tumor base.61,62 An important drawback to plaque radiotherapy is the need for two surgical procedures, one to place the plaque and a second to remove it. Because the average time between the two procedures is 3 days, the overall time demand is favorable compared to EBRT.

Gamma knife radiosurgery (GKR) was initially introduced by Leksell in 1967 to treat intracranial lesions such as brain tumors and vascular abnormalities. In 1987, GKR was introduced as an alternative to enucleation for the treatment of large uveal melanomas.44,46 In GKR, 201 gamma beams from stationary60 cobalt sources intersect at a precise focal point using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography guidance.37 GKR is a four-step procedure including application of a stereotactic frame to the patient’s head, stereotactic image acquisition, treatment planning, and then radiation. Retrobulbar anesthesia may be sufficient to ensure akinesia of the globe during treatment sessions less than 2.5 hours in duration. Additional fixation methods (i.e,. four rectus muscle fixation sutures) may be required for longer sessions.46 The main advantage of GKR is its ability to deliver a single dose of ionizing radiation to a small target, with steep dose fall-off at the margins. These characteristics are crucial to irradiating intraocular tumors while sparing surrounding healthy tissue. The radiation dose of GKR for choroidal metastases (30 Gy over 10 days) is less than for choroidal melanomas (50 Gy over 10 days)5 and is also at the lower threshold of radiation dose of EBRT for choroidal metastases (30–50 Gy over 3–5 weeks). The major drawback is the dependence on large-scale facilities, which are often poorly accessible to patients.5 Recently, GKR has been used to treat choroidal metastases with some success.5,42 In one case series, local tumor control was achieved in all 10 eyes.5 A decrease in tumor size on ultrasonography or MRI was noted in 8 out of 10 patients and no persistent side effects were observed during a median follow-up period of 6.5 months.

In contrast to Gamma knife radiosurgery, Cyber-Knife gamma surgery utilizes a mobile robotic arm to administer frameless stereotactic surgery. Motion correction software adjusts for translational and rotational changes instead of an immobilizing stereotactic frame.71 A newer noninvasive eye fixation monitoring system for CyberKnife radiotherapy obviates the need for muscle sutures, retrobulbar anesthesia, or implanted radio-opaque markers. In contrast to the Gamma knife system, CyberKnife offers fractionated radiotherapy that theoretically causes less radiation damage to nearby structures such as the ciliary body and lens.13,21 To date, CyberKnife surgery is being used in uveal melanomas, but there are no published studies of CyberKnife Gamma surgery in choroidal metastases.

Proton beam radiotherapy (PBT) is a form of charged-particle radiotherapy that delivers heavy, charged particles to a precisely localized lesion through an external beam. Protons travel through matter in straight lines and stop after a certain distance depending on their energy. By modulating the beam energy, a uniform dose can be delivered at any desired depth. Compared with other forms of radiation where gamma-radiation scatter can affect normal tissues, the physical characteristics of proton beams (in particular minimal scatter, tissue-sparing at entry site, increased dose at the end of its range, and sharp fall-off dose at the end of the beam) make PBT ideal for localized irradiation.60 PBT, used for the treatment of uveal melanomas19,20 has recently been applied to choroidal metastases as well. In a retrospective study of 76 eyes treated with PBT, complete regression was observed in 84% within 5 months with no recurrence after a mean follow-up of 10 months. Associated serous retinal detachments resolved in 82% of patients within 3.8 months.65 Traditionally, radio-opaque markers have been surgically placed on the sclera overlying the lesion to ensure accurate localization. As with CyberKnife, development of the “light field” technique for positioning the eye avoids the need for radio-opaque markers. With this technique, the patient is instructed to look at a flashing fixation light.65 The advantages to this technique of PBT compared with other radiotherapies is that it does not require surgical localization, does not depend on lesion characteristics (such as size, location, or number of metastatic foci, as with plaque brachytherapy), and is accomplished with only two fractions. The total radiation dose is 28 cobalt Gy over two treatments. The ocular complications that may arise from PBT include lid burn, madarosis, iris neovascularization, neovascular glaucoma, cataract, radiation retinopathy, and radiation papillopathy.65 PBT treatment, however, is limited to a few tertiary centers.

It remains unclear which modality of radiotherapy is superior for treating choroidal metastases because there is a lack of comparative data. The more important consideration is the choice of treatment dose in order to reduce the risks of radiation retinopathy, usually seen at cumulative doses greater than 45 Gy.49 Particular care in titrating the radiation dosage should be taken in those who are more susceptible to radiation retinopathy, such as patients with diabetes, hypertension, and those on certain chemotherapeutic regiments. The minimum palliative dose for effective lesion regression is also poorly understood. In a study of 58 eyes treated with EBRT, Rosset et al reported that both tumor response and visual acuity are significantly improved if doses higher than 35.5 Gy are administered.52 However, in another study of 42 breast cancer patients undergoing EBRT, Maor et al reported that a dose as small as 25 Gy given in five fractions over 1 week is effective for palliation in uveal metastases.41 Their group favors this shorter, lower dosage treatment strategy, particularly in patients with limited life expectancies.

B. INTRAVITREAL BEVACIZUMAB

Intravitreal VEGF inhibitor therapy is experimental for choroidal metastases. The rationale for using intravitreal injections is to provide maximal drug delivery to the metastatic lesion to inhibit tumor angiogenesis and vascular permeability. Four case reports have described the use of intravitreal bevacizumab in patients with breast carcinoma, colon adenocarcinoma, and NSCLC found to have new choroidal lesions despite systemic therapy.3,32,36,70 In all four case reports, lesions regressed and retinal detachments resolved after one injection of bevacizumab.

In two reports fluorescein angiography was used to monitor the degree of vascular leakage present in the choroidal metastasis before and after injection.3,32 In the first case of a patient with choroidal metastasis from colorectal cancer, the initial fluorescein angiogram showed that the lesion contained numerous subretinal vascular channels that filled unevenly in the early frames and leaked profusely in late frames. One month after intravitreal injection of 1.25 mg bevacizumab, the angiogram showed a 50% reduction in lesion size and significantly less leakage in the late frames. One month after a second injection, there was no leakage whatsoever.32 In the second study of a patient with metastatic breast cancer, initial fluorescein angiogram showed prominent leakage in the region of the choroidal metastasis with involvement of the fovea. Three weeks after injection of 4 mg bevacizumab, the angiogram showed decreased lesion size and reduced leakage in the late phases.3 The theoretical side effects of intravitreal bevacizumab include hemorrhage, and thromboembolic events. With intravitreal injection there is also a risk of endophthalmitis and uveitis.

Taken together, these data suggest that the mechanism for the response to bevacizumab includes both antiangiogenic and antipermeability effects on the new tumor vessels. Despite these promising results, failures have also been reported.36 Further research is needed to determine the role of VEGF inhibitors in treatment of uveal metastases.

C. OTHER THERAPIES

Choroidal metastases have also been treated with transpupillary thermotherapy,29 laser photocoagulation,34 photodynamic therapy,22,25,43,63 cryotherapy, local excision, and even enucleation.27 With the trend favoring therapies designed to spare the eye and vision, we expect to see an expanded role for intravitreal anti-VEGF agents and focused radiotherapy techniques.

D. MERITS OF LOCAL THERAPY

Locally delivered therapy is appropriate when choroidal metastases progress despite treatment with chemotherapy. In other cases, when metastatic work-up does not identify any other lesions besides a choroidal metastasis, local treatment may also be appropriate. Samuel et al reported a case of a single distant metastasis to the choroid from a primary esophageal adenocarcinoma that responded well to radiotherapy alone.56 In these circumstances, patients can be spared systemic side effects of chemotherapy while still receiving palliative benefits. In addition, external beam radiotherapy, Gamma knife, or CyberKnife therapy can be considered in patients who are simultaneously undergoing whole brain radiation or localized radiation elsewhere.

V. Conclusion

With cancer rates rising and cancer survival improving, choroidal metastases will become an increasingly important cause of visual impairment. We anticipate that the median survival after diagnosis of choroidal metastases will also rise. This patient population will therefore need treatments that maximize their vision and quality of life for their longer, but still limited, life expectancy. As our case report illustrates, new targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors can stabilize metastatic disease and induce choroidal regression without the additional need for local therapy. These targeted treatments can be used synergistically with traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy or alone, avoiding toxic side effects such as myelosuppression. The search for additional drug targets in tumor growth, proliferation, and metastasis should expand our options for treating patients with cancer.

For patients with choroidal metastases unresponsive to systemic therapy, emerging local treatments can give patients better vision with less down-time. Gamma knife radiosurgery uses a stereotactic frame and mobile robotic arms to focus radiation treatment on choroidal metastases with less damage to surrounding ocular tissues. CyberKnife and proton beam therapy have eliminated the need for stereotactic frame by using eye fixation software to guide treatment. These techniques require less radiation than traditional external beam radiotherapy, and we can therefore expect less short-term and long-term vision loss.

Other local treatments, such as intravitreal injections of bevacizumab, are promising but need more research. Several case reports have demonstrated that intravitreal bevacizumab can induce choroidal lesion regression, possibly through its anti-angiogenic effects on the tumor’s blood supply. Future studies may reveal whether other monoclonal antibodies, or even tyrosine kinase inhibitors, can provide additional benefit if delivered by intra-vitreal injection.

Choroidal metastases are, of course, part and parcel of systemic carcinoma, and as seen in our case and others, choroidal lesion regression is often associated with regression of metastases elsewhere. Given these findings, choroidal metastases may have an under-appreciated role in the monitoring of systemic disease. When a new therapy is initiated, serial eye exams may provide a noninvasive way of assessing response. Studies delineating how well the regression or advancement of choroidal metastases correlates with overall response to chemotherapy will help to determine the value of the ophthalmologic examination in assessing the overall treatment response.

In summary, the options for treatment of choroidal metastases have expanded substantially over the past decade. These emerging therapies offer patients better tolerated, shorter treatments with less damage to uninvolved ocular tissues.

VI. Method of Literature Search

A systemic Medline database search on PubMed (13 September 2010) was conducted using the following MeSH headings: choroidal neoplasm, neoplasm metastasis, and therapeutics. Relevant articles from the past 10 years were retrieved. Further articles were identified from the reference lists of the retrieved articles. This review primary relied on articles written in English. However, non-English language articles that had abstracts translated into English were also reviewed. When cited, these articles are identified as [abstract only]. Emerging systemic treatments for metastatic cancers were identified based on evidence-based consensus guidelines from the National Comprehensive Cancer Network Web site (www.nccn.org), 13 September 2010.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Dr. Julie Brahmer is on the advisory board for Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and ImClone. The authors reported no proprietary or commercial interest in any product mentioned or concept discussed in this article.

References

- 1.Altekruse SF, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amer R, et al. Treatment options in the management of choroidal metastases. Ophthalmologica. 2004;218(6):372–7. doi: 10.1159/000080939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amselem L, Cervera E, Diaz-Llopis M, et al. Intravitreal bevacizumab (avastin) for choroidal metastasis secondary to breast carcinoma: short-term follow-up. Eye (Lond) 2007;21(4):566–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6702647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battikh MH, Ben Yahia S, Ben Sayah MM, et al. Choroid metastases revealing pulmonary adenocarcioma resolved with chemotherapy [abstract only] Rev Pneumol Clin. 2004;60(6 Pt 1):353–6. doi: 10.1016/s0761-8417(04)72149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bellmann C, Fuss M, Holz FG, et al. Stereotactic radiation therapy for malignant choroidal tumors: preliminary, short-term results. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(2):358–65. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(99)00081-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biswal BM. Restoration of vision following combination chemotherapy of nasopharyngeal carcinoma choroidal metastases. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2001;37(5):484. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bloch RS, Gartner S. The incidence of ocular metastatic carcinoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85(6):673–5. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1971.00990050675005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinkley JR., Jr Response of a choroidal metastasis to multiple-drug chemotherapy. Cancer. 1980;45(7):1538–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800401)45:7<1538::aid-cncr2820450704>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, et al. Breast cancer. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(2):122–92. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chabner BA, Roberts TG., Jr Timeline: chemotherapy and the war on cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(1):65–72. doi: 10.1038/nrc1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Char DH. Treatment of choroidal metastases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1991;109(3):333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(11):1160–74. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0707704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Daftari IK, Petti PL, Larson DA, et al. A noninvasive eye fixation monitoring system for CyberKnife radiotherapy of choroidal and orbital tumors. Med Phys. 2009;36(3):719–24. doi: 10.1118/1.3070537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eberhard DA, Johnson BE, Amler LC, et al. Mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor and in KRAS are predictive and prognostic indicators in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer treated with chemotherapy alone and in combination with erlotinib. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(25):5900–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engstrom PF, Arnoletti JP, Benson AB, 3rd, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colon cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(8):778–831. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gazdar AF. Personalized medicine and inhibition of EGFR signaling in lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(10):1018–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe0905763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George B, Wirostko WJ, Connor TB, et al. Complete and durable response of choroid metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer with systemic bevacizumab and chemotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(5):661–2. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819c9a73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gordon MS, Cunningham D. Managing patients treated with bevacizumab combination therapy. Oncology. 2005;69(Suppl 3):25–33. doi: 10.1159/000088481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gragoudas ES, Goitein M, Verhey L, et al. Proton beam irradiation. An alternative to enucleation for intraocular melanomas. Ophthalmology. 1980;87(6):571–81. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(80)35212-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gragoudas ES, Goitein M, Koehler AM, et al. Proton irradiation of small choroidal malignant melanomas. Am J Ophthalmol. 1977;83(5):665–73. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(77)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haas A, Pinter O, Papaefthymiou G, et al. Incidence of radiation retinopathy after high-dosage single-fraction gamma knife radiosurgery for choroidal melanoma. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(5):909–13. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harbour JW. Photodynamic therapy for choroidal metastasis from carcinoid tumor. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(6):1143–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hudis CA. Trastuzumab—mechanism of action and use in clinical practice. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(1):39–51. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra043186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imai K, Takaoka A. Comparing antibody and small-molecule therapies for cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(9):714–27. doi: 10.1038/nrc1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Isola V, Pece A, Pierro L. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin of choroidal malignancy from breast cancer. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(5):885–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jost M, Kari C, Rodeck U. The EGF receptor—an essential regulator of multiple epidermal functions. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10(7):505–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kanthan GL, Jayamohan J, Yip D, et al. Management of metastatic carcinoma of the uveal tract: an evidence-based analysis. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2007;35(6):553–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2007.01550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerbel RS. Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(19):2039–49. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0706596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kiratli H, Bilgic S. Transpupillary thermotherapy in the management of choroidal metastases. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2004;14(5):423–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohler G, Milstein C. Continuous cultures of fused cells secreting antibody of predefined specificity. Nature. 1975;256(5517):495–7. doi: 10.1038/256495a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosmas C, Malamos NA, Tsavaris N, et al. Chemotherapy-induced complete regression of choroidal metastases and subsequent isolated leptomeningeal carcinomatosis in advanced breast cancer: A case report and literature review. J Neurooncol. 2000;47(2):161–5. doi: 10.1023/a:1006449215047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuo IC, Haller JA, Maffrand R, et al. Regression of a subfoveal choroidal metastasis of colorectal carcinoma after intravitreous bevacizumab treatment. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(9):1311–3. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Letson AD, Davidorf FH, Bruce RA., Jr Chemotherapy for treatment of choroidal metastases from breast carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;93(1):102–6. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90707-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levinger S, Merin S, Seigal R, et al. Laser therapy in the management of choroidal breast tumor metastases. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 2001;32(4):294–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lim JI, Petrovich Z. Radioactive plaque therapy for metastatic choroidal carcinoma. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(10):1927–31. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00252-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin CJ, Li KH, Hwang JF, et al. The effect of intravitreal bevacizumab treatment on choroidal metastasis of colon adenocarcinoma—case report. Eye (Lond) 2010;24(6):1102–3. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindquist C. Gamma knife radiosurgery. Semin Radiat Oncol. 1995;5(3):197–202. doi: 10.1054/SRAO00500197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Logani S, Gomez H, Jampol LM. Resolution of choroidal metastasis in breast cancer with high estrogen receptors. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(4):451–2. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080160029012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(21):2129–39. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Manquez ME, Brown MM, Shields CL, et al. Management of choroidal metastases from breast carcinomas using aromatase inhibitors. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2006;17(3):251–6. doi: 10.1097/01.icu.0000193105.22960.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maor M, Chan RC, Young SE. Radiotherapy of choroidal metastases: breast cancer as primary site. Cancer. 1977;40(5):2081–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2081::aid-cncr2820400515>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marchini G, Babighian S, Tomazzoli L, et al. Gamma knife stereotactic radiosurgery of ocular metastases: a case report. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 1995;64(Suppl 1):67–71. doi: 10.1159/000098765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mauget-Faysse M, Gambrelle J, Maftouhi Quaranta-El, et al. Photodynamic therapy for choroidal metastasis from lung adenocarcinoma. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2006;84(4):552–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0420.2006.00648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Modorati G, Miserocchi E, Galli L, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for uveal melanoma: 12 years of experience. Br J Ophthalmol. 2009;93(1):40–4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2008.142208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morris PG, Oda J, Heinemann MH, et al. Choroidal metastases from esophageal adenocarcinoma responding to chemotherapy with cisplatin and irinotecan. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(22):e372–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mueller AJ, Talies S, Schaller UC, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery of large uveal melanomas with the gamma-knife. Ophthalmology. 2000;107(7):1381–7. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00150-0. discussion 13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munzone E, Nole F, Sanna G, et al. Response of bilateral choroidal metastases of breast cancer to therapy with trastuzumab. Breast. 2005;14(5):380–3. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pao W, Miller V, Zakowski M, et al. EGF receptor gene mutations are common in lung cancers from “never smokers” and are associated with sensitivity of tumors to gefitinib and erlotinib. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101(36):13306–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405220101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Parsons JT, Bova FJ, Fitzgerald CR, et al. Radiation retinopathy after external-beam irradiation: analysis of time-dose factors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994;30(4):765–73. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perls M. Beiträge zur geschwulstlehre [abstract only] Virchows Archiv. 1872;1(4):437–67. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A, et al. Cutaneous side-effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(7):491–500. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosset A, Zografos L, Coucke P, et al. Radiotherapy of choroidal metastases. Radiother Oncol. 1998;46(3):263–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00209-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rudoler SB, Corn BW, Shields CL, et al. External beam irradiation for choroid metastases: identification of factors predisposing to long-term sequelae. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;38(2):251–6. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rudoler SB, Shields CL, Corn BW, et al. Functional vision is improved in the majority of patients treated with external-beam radiotherapy for choroid metastases: a multivariate analysis of 188 patients. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):12 44–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saltz LB, Clarke S, Diaz-Rubio E, et al. Bevacizumab in combination with oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy as first-line therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a randomized phase III study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(12):2013–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Samuel J, Flood TP, Agbemadzo B, et al. Choroidal metastasis from adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Retina. 2003;23(6):874–7. doi: 10.1097/00006982-200312000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(5):1215–21. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shields CL. Plaque radiotherapy for the management of uveal metastasis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 1998;9(3):31–7. doi: 10.1097/00055735-199806000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shields CL, Shields JA, Gross NE, et al. Survey of 520 eyes with uveal metastases. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(8):1265–76. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30148-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shields CL, Shields JA, De Potter P, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for the management of uveal metastasis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1997;115(2):203–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1997.01100150205010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shields CL, Shields JA, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for uveal melanoma: Long-term visual outcome in 1106 consecutive patients. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(9):1219–28. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.9.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shields CL, Naseripour M, Cater J, et al. Plaque radiotherapy for large posterior uveal melanomas (> or =8-mm thick) in 354 consecutive patients. Ophthalmology. 2002;109(10):1838–49. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)01181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Soucek P, Cihelkova I. Photodynamic therapy with verteporfin in subfoveal choroidal metastasis of breast carcinoma (a controlled case) Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2006;27(6):725–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stephens RF, Shields JA. Diagnosis and management of cancer metastatic to the uvea: a study of 70 cases. Ophthalmology. 1979;86(7):1336–49. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(79)35393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tsina EK, Lane AM, Zacks DN, et al. Treatment of metastatic tumors of the choroid with proton beam irradiation. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(2):337–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wharam MD, Jr, Schachat AP. Chapter 45: Choroidal metastasis. In: Ryan SJ, Schachat AP, Wilkinson CP, editors. Retina. 4. Philadelphia: Elsevier Inc; 2006. pp. 811–8. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Widakowich C, de Castro G, Jr, de Azambuja E, et al. Review: side effects of approved molecular targeted therapies in solid cancers. Oncologist. 2007;12(12):1443–55. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wiegel T, Bottke D, Kreusel KM, et al. External beam radiotherapy of choroidal metastases—final results of a prospective study of the German Cancer Society (ARO 95-08) Radiother Oncol. 2002;64(1):13–8. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(02)00134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wong ZW, Phillips SJ, Ellis MJ. Dramatic response of choroidal metastases from breast cancer to a combination of trastuzumab and vinorelbine. Breast J. 2004;10(1):54–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4741.2004.09614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yao HY, Horng CT, Chen JT, et al. Regression of choroidal metastasis secondary to breast carcinoma with adjuvant intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010;88(7):282–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2009.01684.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zorlu F, Selek U, Kiratli H. Initial results of fractionated CyberKnife radiosurgery for uveal melanoma. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(1):111–7. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-9811-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]