Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Most women having mastectomy for breast cancer treatment do not have breast reconstruction.

OBJECTIVE

To examine correlates of reconstruction and determine if there is a significant unmet need for reconstruction.

DESIGN

Los Angeles and Detroit SEER registries utilized rapid case ascertainment to identify a sample of women diagnosed with breast cancer. Subjects were surveyed a median of 9mos post-diagnosis initially; those remaining disease-free were surveyed again at 4yrs to determine the frequency of immediate and delayed reconstruction, and patient attitudes toward the procedure.

SETTING

Two metropolitan area population-based SEER registries were used to identify subjects; Latina/Black women were oversampled to ensure adequate minority representation.

PARTICIPANTS

Women age 20-79 with DCIS and stage 1-3 invasive carcinoma diagnosed between 6/05-2/07 were eligible if they could complete a questionnaire in English or Spanish. Initial survey was sent to 3252 women. 2290 completed it. 1536 completed the follow-up survey. The 485 undergoing initial mastectomy and remaining disease-free at follow-up are this report’s subject.

MAIN OUTCOMES/MEASURES

Participants were surveyed a mean of 9mos and again at 50mos post-diagnosis. Latina and Black women were oversampled.

RESULTS

Response rates in the initial and follow-up surveys were 73% and 68%, respectively (overall, 50%). Of 485 patients reporting mastectomy at initial survey and remaining disease-free, 41.6% had reconstruction—24.8% immediate, 16.8% delayed. Factors significantly associated with not receiving reconstruction were Black race, lower education level, older age, major co-morbidity, and receipt of chemotherapy. Only 13% of women were dissatisfied with reconstruction decision making, but dissatisfaction was higher among non-whites in the sample(p=.032). The most common patient-reported reasons for not having reconstruction were the desire to avoid additional surgery and feeling that it was not important, but 36% expressed fear of implants. Reasons for avoiding reconstruction and systems barriers to care varied by race; barriers were more common among non-whites. Residual demand for reconstruction at 4yrs was low, with only 30/263 non-reconstructed respondents still considering the procedure.

CONCLUSIONS/RELEVANCE

Reconstruction rates largely reflect patient demand; most patients are satisfied with reconstruction decision making. Specific approaches are needed to address lingering patient-level and systems factors negatively impacting reconstruction use in minority women.

Keywords: immediate reconstruction, delayed reconstruction, implants, patient choice, breast reconstruction

Universal coverage for postmastectomy breast reconstruction was mandated following enactment of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act in the United States in 1998. In spite of guaranteed insurance coverage, the majority of women having a mastectomy for breast cancer treatment do not undergo breast reconstruction, with rates of reconstruction ranging from 25%-35% in population-based studies1, 2 of women treated between 2003-2007. Even among women treated in National Cancer Institute-designated cancer centers participating in the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, just over 50% of those having mastectomy underwent reconstruction.3 Variations in rates of reconstruction use have been associated with age, insurance status, ethnicity, and supply of reconstructive surgeons.1-3 This, coupled with evidence of significant between-surgeon variation in discussion of reconstruction,4 and patient receipt of mastectomy and breast reconstruction,5 has suggested that patients’ needs for reconstruction may not be fully addressed. These concerns resulted in the passage of a New York State law in 2010 mandating that surgeons discuss the availability of breast reconstruction with patients prior to breast cancer treatment, provide information about insurance coverage, and refer them to a hospital where reconstruction is available if necessary.6 However, little is known about patient perceptions regarding reconstruction, and it is unclear whether there is a significant unmet need for breast reconstruction. In addition, most studies that have examined reconstruction do not include patients who received the surgical procedure later (delayed reconstruction). We have previously reported that delayed reconstruction was infrequent in a population-based sample of women diagnosed in 2002, and found that only 59% of patients in that study who did not undergo reconstruction felt that they were adequately informed about the procedure.7 The purpose of this study was to examine the rates of both immediate and delayed breast reconstruction, and correlates of their use, in a diverse, population-based sample treated in a more recent time period to determine if significant gaps in awareness regarding breast reconstruction persist. In addition, we sought to examine patient attitudes toward reconstruction and identify whether there is a significant unmet need for reconstruction after completion of cancer treatment.

Methods

Study Population and Data Collection

Women in the Los Angeles, California, and Detroit, Michigan metropolitan areas aged 20-79 years who were diagnosed with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or invasive breast cancer between June 2005-February 2007, and reported to the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program registries in the 2 regions, were eligible for initial sample selection. Patients were excluded if they had stage IV breast cancer, died prior to the initial survey, or could not complete the initial questionnaire in English or Spanish. Asian women in Los Angeles also were excluded because of enrollment in other studies. Latina (in Los Angeles) and Black (in Los Angeles and Detroit) patients were oversampled to ensure sufficient representation of racial/ethnic minorities.

Eligible patients were identified via rapid case ascertainment as they were reported monthly to the collaborating SEER registries. Physicians were notified of our intent to contact patients, followed by a patient mailing consisting of a letter, survey materials, and a $10 cash gift to eligible study participants. All materials were sent in English and Spanish to those with Spanish surnames. Patients were initially interviewed at an average time of 9 months after diagnosis (completion window: mean, 9 months; range, 5-14 months). A follow-up survey was sent to those who completed the baseline survey approximately 4 years after diagnosis (completion window: mean, 50 months; range, 36-65 months). The Dillman survey method was used for both surveys to encourage response.10

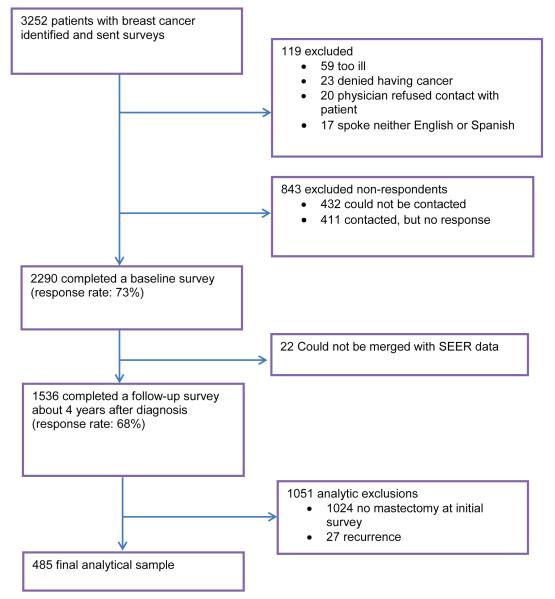

Figure 1 shows the decay in the sample from initial accrual of patients through to the selection of the sample for the analysis in this study: 3252 patients were initially identified and sent a baseline survey; 2290 patients (73%) completed that survey; and 1536 patients completed the follow-up survey. The analytic sample for this study is the 485 patients who reported mastectomy at the initial survey, completed the follow-up survey, and indicated that they did not have a recurrence of breast cancer. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Michigan, University of Southern California, and Wayne State University.

Figure 1. CONSORT Flow Diagram of Patients and Decay in the Sample.

SEER, National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results.

Measures

A primary outcome of interest was a binary variable that indicated whether or not a patient received breast reconstruction at any time since mastectomy, obtained from both surveys. The second outcome of interest was patient satisfaction with different aspects of the reconstruction decision-making process among all patients, obtained from the follow-up survey. Patients were asked to agree/disagree with statements regarding their satisfaction with aspects of the breast reconstruction decision-making process:(1) Being satisfied with the decision about whether or not to have reconstruction;(2) Not regretting the choice they made regarding whether or not to have breast reconstruction;(3) Being satisfied about being informed about the issues important to breast reconstruction. The response category format was a Likert scale that ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The items were re-coded to obtain congruent valence and averaged to make a scale. We dichotomized the scale score as low satisfaction (<3) or higher (≥3). In addition, we examined the reasons why patients did not have breast reconstruction or delayed reconstruction across 2 dimensions:1) Patient factors, such as their attitudes toward reconstruction (i.e., worry; too much time off work or away from family) or clinical reasons; and 2) Systems factors. Patients were asked to what extent each reason contributed to their decision, ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“a lot”) using a Likert scale.

The independent variables considered in this study included patient demographics, patient clinical/treatment factors, and site (Detroit versus Los Angeles). Patient demographics included age, education, race/ethnicity, partner status, income, insurance types, and smoking status. Patient clinical factors included cancer stage, presence of key medical comorbidities (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, diabetes, stroke), and breast size. Treatment factors included the receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of radiation, and timing of reconstruction (delayed or immediate reconstruction after mastectomy). All these variables were self-reported except cancer stage. The cancer stage classification used was the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system,11 and was obtained from SEER.

Statistical Analysis

We first conducted an analysis comparing key baseline categorical variables between responders (those who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys) to non-responders using Chi-squared tests. We then calculated summary statistics on our sample population using percentages for categorical variables, and the mean and standard deviations for continuous variables. Logistic regression was used to assess the odds of patients not receiving reconstruction after mastectomy. The independent variables for this model included age, partner status, education, race/ethnicity, income, insurance types, comorbidities, pre-diagnosis bra cup size, cancer stage, receipt of radiation, receipt of chemotherapy, receipt of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM), and SEER site. Similarly, we used logistic regression to model the odds of being dissatisfied with the decision-making process. The independent variables for this model included the status of reconstruction (yes versus no), age, education level, race/ethnicity, marriage/partner status, income, insurance type, cancer stage, and SEER site. To achieve parsimony of the regression models, we used a backward variable selection method to eliminate the variables that did not reach the statistical significance level of 0.10. Finally, we described the distribution of responses to a list of reasons why women did not receive reconstruction or delayed the procedure. This list was based on the percentages of patients who reported that a given issue contributed to their decision to omit or delay reconstruction (“quite a bit” or “a lot” versus “somewhat” to “not at all”). We examined the difference in these percentages across racial/ethnic groups using Mantel-Haenszel tests.

All the descriptive and regression analyses described above were weighted using survey procedures (e.g., PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC for logistic regression) to account for differential probabilities of sample selection and non-response, which made our statistical inference more representative of the population. An analytic weight was created that accounted for the initial sampling design (oversampling of Blacks and Latinas, and disproportionate selection across geographic sites) and differential non-response in the 2 waves of the surveys.12 All analyses used SAS software, Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

An analysis of sampled patients comparing non-respondents with respondents who completed both the initial and the follow-up surveys showed that there were no significant differences by age at diagnosis. However, compared with respondents, non-respondents to the follow-up survey were more likely to be Black (35.2% versus 26.7%;p<0.001) or Latina (17.2% versus 13.3%;p=0.002), more likely to have stage II or III disease (54.9% versus 37.8%;p<0.001), and more likely to have received mastectomy (37.5% versus 30.8%;p<0.001).

The characteristics of the patient population are summarized in Table 1. The mean age was 55.8 years; 42.4% had a high-school–level education or less, and 64.3% had stage I or II breast cancer. Postmastectomy radiotherapy was reported by 33.0%, and 11.6% underwent a CPM. Overall, 41.6% of the 485 patients treated with mastectomy who remained disease-free had breast reconstruction: 24.8% (n=146) of the procedures were done at the time of mastectomy, and 16.8% (n=76) were delayed. The most common type of reconstruction was with implants or tissue expanders, used in 61.9% of those undergoing reconstruction. A multivariable regression analysis of factors associated with not undergoing any breast reconstruction is shown in Table 2. Black patients, those with a high school or lower education level, those without private insurance, women with any major co-morbid condition, older women, and those residing in Los Angeles County were significantly less likely to undergo reconstruction than their counterparts. Patients who received chemotherapy were also significantly less likely to undergo reconstruction.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Breast Cancer Cases with Mastectomy (n=485)

| Variables | Number | Weighted %‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction timing | ||

| No reconstruction | 263 | 58.4 |

| Immediate reconstruction | 146 | 24.8 |

| Delayed reconstruction | 76 | 16.8 |

| Type of reconstruction | ||

| Autologous tissue | 68 | 38.1 |

| Implant | 141 | 61.9 |

| Age, mean (SE), y | 485 | 55.8(0.7) |

| BMI, mean (SE) | 459 | 28.7(0.4) |

| Breast size | ||

| A or B | 168 | 35.7 |

| C | 165 | 37.9 |

| D and above | 131 | 26.5 |

| Race | ||

| Non-Black, Non-Latina | 233 | 40.9 |

| Black | 104 | 15.3 |

| Latina | 148 | 43.7 |

| Education level | ||

| High school or less | 174 | 42.2 |

| Some college or more | 306 | 57.8 |

| Insurance type | ||

| None | 39 | 10.0 |

| Private | 283 | 57.7 |

| Medicaid | 47 | 12.1 |

| Medicare | 99 | 20.2 |

| Income | ||

| < $20,000 | 84 | 17.6 |

| $20,000 to $69,999 | 167 | 34.5 |

| ≥ $70,000 | 146 | 26.8 |

| Unknown | 88 | 21.1 |

| Married or partnered | ||

| Yes | 288 | 59.8 |

| No | 195 | 40.2 |

| One or more chronic condition(s)† | ||

| Yes | 98 | 19.6 |

| No | 387 | 80.4 |

| Smoking | ||

| Yes | 73 | 13.6 |

| No | 409 | 86.4 |

| AJCC stage | ||

| 0 | 99 | 14.2 |

| I | 133 | 24.7 |

| II | 164 | 39.6 |

| III | 87 | 21.5 |

| Postmastectomy radiation therapy receipt | ||

| Yes | 144 | 33.0 |

| No | 322 | 67.0 |

| Chemotherapy receipt | ||

| Yes | 278 | 65.0 |

| No | 198 | 35.0 |

| Contralateral prophylactic mastectomy | ||

| Yes | 56 | 11.6 |

| No | 429 | 88.4 |

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, heart disease, diabetes, stroke

Percentages are weighted to account for the sample design and non-response.

Abbreviations: SE, standard error; BMI, body mass index; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Table 2.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Non-receipt of Reconstruction (n=471a)

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 1.82 | 0.99 to 3.31 | 0.050 |

| Major comorbidities | |||

| No | 1.00 | ||

| Yes | 2.27 | 1.01 to 5.11 | 0.048 |

| Age, 10 years | 2.53 | 1.77 to 3.61 | <.0001 |

| Education level | |||

| Some college or higher | 1.00 | ||

| High school or less | 4.49 | 2.31 to 8.72 | <.0001 |

| Insurance | 0.044 | ||

| Private | 1.00 | ||

| Medicaid | 2.72 | 1.11 to 6.64 | |

| Medicare | 2.43 | 0.87 to 6.79 | |

| None | 2.81 | 1.06 to 7.50 | |

| Race | 0.004 | ||

| Non-Black/Non-Latina | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 2.16 | 1.11 to 4.20 | |

| Latina | 0.62 | 0.28 to 1.37 | |

| Site | |||

| Detroit | 1.00 | ||

| Los Angeles | 1.90 | 1.03 to 3.50 | 0.041 |

30 patients were not included because of missing values for dependent or independent variables.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Most women reported being satisfied with the decision-making process regarding reconstruction: the mean satisfaction score was 3.9 (SE, 0.05) on a 5-point Likert scale. About 13.3% of women reported being dissatisfied with the decision-making process (score <3). Table 3 shows correlates of dissatisfaction with the reconstruction decision-making process. Dissatisfaction with the decision-making process was associated with being Black or Latina (p=0.032), but not with lower income levels or level of education.

Table 3.

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Dissatisfaction with the Reconstruction Decision-Making Process (n=470a)

| Variables | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Income | 0.148 | ||

| >$70,000 | 1.00 | ||

| <$20,000 | 2.00 | 0.75 to 5.34 | |

| $20,000 to $69,999 | 1.29 | 0.53 to 3.11 | |

| Unknown | 0.58 | 0.16 to 2.16 | |

| Education level | |||

| Some college or higher | 1.00 | ||

| High school or less | 1.69 | 0.76 to 3.73 | 0.195 |

| Race | 0.032 | ||

| Non-Black/Non-Latina | 1.00 | ||

| Black | 2.87 | 1.27 to 6.51 | |

| Latina | 2.03 | 0.89 to 4.67 |

15 patients were not included because of missing values for dependent or independent variables.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval

Reasons for not undergoing reconstruction are summarized in Table 4 for the 263 women treated with mastectomy alone. Common reasons among women of all racial/ethnic groups were the desire to avoid additional surgery (48.5%) or the feeling that reconstruction was not important (33.8%). However, ethnic minority groups were less likely to report the desire to avoid additional surgery (70.0% for non-Black, non-Latina patients versus 39.7% and 34.1% for Blacks and Latinas, respectively;p<0.001) or that reconstruction was not important (42.4% for non-Black, non-Latina patients versus 21.6% and 31.3% for Blacks and Latinas, respectively;p=0.043). Fear of implants (36.3%) was another commonly reported reason for not undergoing reconstruction. Concerns about interference with the detection of cancer and lack of awareness of the availability of reconstruction were cited by 23.9% and 18.1% of the sample, respectively. There were significant racial/ethnic gradients for some of the other reasons given for not undergoing reconstruction. More Latinas reported concerns about interference with cancer detection or complications of the procedure, and not being able to take time off from work or family. More Blacks and Latinas reported the systems barrier of having no insurance coverage.

Table 4.

Reasons Given by Patients for Not Getting Reconstruction (n=263)

| Total | Non-Black, Non- Latina |

Black | Latina | p-value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %‡ | % | % | % | % | |

| Patient factors | |||||

| Did not want additional surgery | 48.5 | 70.0 | 39.7 | 34.1 | <0.001 |

| Was not important | 33.8 | 42.4 | 21.6 | 31.3 | 0.043 |

| Fear of implants | 36.3 | 34.4 | 38.8 | 40.7 | 0.731 |

| Concerned about interference with detection of recurrence |

23.9 | 16.1 | 18.6 | 32.5 | 0.066 |

| Concerned about possible complications | 33.6 | 27.9 | 20.4 | 43.8 | 0.017 |

| Could not take much time off work or family | 16.1 | 8.9 | 9.5 | 24.7 | 0.022 |

| Systems factors | |||||

| Did not know was an option | 18.1 | 12.7 | 27.7 | 18.6 | 0.514 |

| Trouble finding surgeon | 5.6 | 4.2 | 10.6 | 4.7 | 0.514 |

| No insurance coverage | 11.8 | 2.2 | 23.7 | 18.6 | 0.001 |

| Surgeon did not take insurance | 7.8 | 2.8 | 16.8 | 8.5 | 0.085 |

P-value tests for differences in item response across race/ethnic groups.

Percent that indicated the factor contributed “quite a bit” or “a lot” to the decision to not have breast reconstruction. Percentages are weighted to account for the sample design and non-response.

Most of the 76 patients who received delayed breast reconstruction reported treatment-related reasons for delaying reconstruction, including the need to focus on cancer treatment (68.7%), or the need to accommodate chemotherapy (50.7%) or radiation (26.3%)(Table 5). Fewer than 15% indicated they were unaware of the option of breast reconstruction at the time of their breast cancer surgery, or that they had problems with insurance. There was little residual demand for breast reconstruction among women who had not undergone the procedure by 4 years after diagnosis; only 30 (11.4%) of the 263 respondents who had not had reconstruction indicated they were still considering breast reconstruction.

Table 5.

Reasons Given by Patients for Delay in Breast Reconstruction (n=76)

| %† | |

|---|---|

| Patient factors: clinical | |

| Needed radiation therapy | 26.3 |

| Needed chemotherapy | 50.7 |

| Focused on treating the cancer | 68.7 |

| Patient factors: attitudes | |

| Not sure wanted reconstruction | 10.1 |

| Too much time off work or family | 6.7 |

| Systems factors | |

| Did not know of the reconstruction option | 14.3 |

| Trouble finding surgeon to perform reconstruction | 0.0 |

| Problems with initial breast surgery | 8.1 |

| No insurance coverage | 10.3 |

Percent that indicated the factor contributed “quite a bit” or “a lot” to the decision to delay breast reconstruction. Percentages are weighted to account for the sample design and non-response.

Discussion

Our study suggests that the rate of breast reconstruction after mastectomy has been relatively stable over time in 2 large, diverse SEER catchment areas. In our earlier study of women identified in the Detroit and Los Angeles SEER registries, and treated between December 2001 and January 2003, 36% of those undergoing mastectomy had immediate reconstruction and an additional 12% underwent delayed reconstruction.7, 13 In our current sample of patients diagnosed between July 2005 and February 2007 from the same SEER registries, the overall rate of reconstruction was 42% (25% immediate and 17% delayed). These findings are consistent with the 25% to 29% increase in reconstruction seen in statewide data from California between 2003 and 2007.2 Albornoz et al14 used the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database to examine rates of immediate reconstruction in 2008 and found that 37.8% of patients undergoing mastectomy had immediate reconstruction.

Although the optimal rate of breast reconstruction is uncertain, our results suggest that patient demand, and clinical and treatment factors largely determined receipt of the procedure. A lack of interest in additional surgery at the time of cancer diagnosis was the primary reason for not getting reconstruction, both in our current patient sample and in an older sample reported by our research team.7, 13 Others have also found that patients’ feelings that reconstruction was not important and patients’ desires to avoid additional surgery are the major factors responsible for low rates of reconstruction.15 While feeling that reconstruction is not important may seem counterintuitive, breast-conserving surgery (BCS) with radiation is an alternative way to maintain a breast that is an option for the majority of women with early-stage breast cancer,16 involves a smaller surgical procedure with more rapid recovery than mastectomy with reconstruction, and results in a sensate breast mound. In contrast, mastectomy with reconstruction often requires additional surgical procedures, and the reconstructed breast lacks normal sensation, making BCS the preferred choice for some women desiring to maintain a breast. Greenberg et al3 have demonstrated a strong inverse correlation between institutional rates of BCS and mastectomy with reconstruction (r=−0.80,p=0.02), but no correlation between institutional rates of mastectomy alone and BCS, or mastectomy alone and mastectomy plus reconstruction.

We found that 17% of mastectomy-treated patients delayed reconstruction. This finding from a population study is somewhat higher than what was seen in a series from the MD Anderson Cancer Center where 8% of women had delayed reconstruction between 15-27 months after mastectomy,17 but suggests that most women desiring reconstruction have access to immediate breast reconstruction. Patient report of reasons for delaying reconstruction clearly showed that coordinating treatment delivery was the major factor in the decision to forgo reconstruction in our study population. Another reassuring finding from this study is that 4 years after diagnosis, only 30 (11.4%) of the 263 patients who had not had reconstruction were still considering it.

Importantly, our results suggest some lingering barriers to breast reconstruction. Black patients were less likely than non-Black, non-Latina patients to receive reconstruction. Additionally, patients without private insurance plans were less likely to receive reconstruction. Patient-reported reasons for not getting reconstruction suggested patient knowledge- and attitude-related barriers, and systems issues. One-fifth of women who did not get reconstruction reported a lack of knowledge regarding it. Many women continue to report fear of implants as one reason for forgoing reconstruction, despite their proven safety.18-20 One-fourth of women who did not get reconstruction in our sample reported concern about potential interference with cancer detection as a decision factor, in spite of the clinical evidence not supporting this contention.20, 21 Furthermore, Latinas were more likely than other groups to endorse these beliefs. Results also suggest that there are lingering systems-related barriers for some patient subgroups—particularly for Blacks, one-fifth of whom reported insurance-related barriers (versus 2% of non-Black, non-Latina patients, and 18.6% of Latinas;p=0.001). These findings are consistent with a prior study in this patient sample examining racial and ethnic disparities in the use of reconstruction in which minority women were found to have lower satisfaction with both information received and decision making than Whites.1 Other studies have also observed lower rates of reconstruction among Black, Asian,2, 22 and Latina women.15

Some aspects of the study methods merit comment. A strength of the study was its diverse population-based sample and rigorous attention to measurement.8, 12 The results are limited to women from 2 metropolitan areas and may not reflect access to reconstruction nationally, particularly in rural areas where plastic surgeons may be less available. The study was retrospective in design, and patient recall of their clinician encounters may have varied over time. Finally, there was substantial decay in the longitudinal sample, which may have introduced selection bias.

In summary, we found that women are largely satisfied with breast-reconstruction decision making and that stable rates of receipt of the procedure largely reflect patient demand. A minority of women delayed reconstruction within 4 years of cancer diagnosis, and delay was largely explained by relevant clinical and treatment-related factors. These findings suggest that legislative mandates to change the approach to patient education, such as a recent New York State law passed in 2010, are likely to be less effective than more ground-level practice initiatives such as patient decision tools or encouraging input from plastic surgeons at time of treatment decision making.5, 7 Our study does suggest that there is room for improved education regarding the safety of breast implants and impact of reconstruction on follow-up surveillance, information which could be readily addressed through decision tools. Finally, there is a need to develop specific approaches to address patient-level land systems factors that negatively impacted the use of reconstruction among minority women.

Acknowledgements

The design and conduct of the study was supported by Grants No. R01CA109696, R01 CA139014, and R21CA122467 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the University of Michigan; by a Mentored Research Scholar Grant No. MRSG-09-145-01 from the American Cancer Society (RJ); and by Established Investigator Award No. K05CA111340 in Cancer Prevention, Control, Behavioral, and Population Sciences Research from the NCI (SK). The collection of the data was supported by the California Department of Public Health as part of the statewide cancer reporting program mandated by California Health and Safety Code §103885; the NCI SEER Program under Contract No. N01-PC-35139 awarded to the University of Southern California, and Contract No. N01-PC-54404 and Agreement No. 1U58DP00807-01 awarded to the Public Health Institute; and by NCI SEER under Contract No. N01-PC-35145.

Corresponding Author Signature for the Acknowledgement statement:

Footnotes

All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Author Contributions: Drs. Monica Morrow and Steven Katz had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Steven Katz, Monica Morrow

Acquisition of data: Ann Hamilton, John Graff

Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors

Drafting of the manuscript: Monica Morrow

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: all authors

Statistical analysis: Steven Katz

Obtained funding: Steven Katz

Administrative, technical, and material support: Monica Morrow, Steven Katz

Study supervision:Steven Katz

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

All financial disclosure information is accurate, complete, and up-to-date.

Contributor Information

Monica Morrow, Breast Service, Department of Surgery, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, New York.

Yun Li, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; yunlisph@umich.edu.

Amy K. Alderman, The Swan Center for Plastic Surgery, Alpharetta, Georgia; amyaldermanmd@yahoo.com.

Reshma Jagsi, Department of Radiation Oncology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; rjagsi@med.umich.edu.

Ann S. Hamilton, Department of Preventive Medicine, Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California; ahamilt@med.usc.edu.

John J. Graff, Department of Radiation Oncology, Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, New Brunswick, New Jersey; graffjj@umdnj.edu.

Sarah T. Hawley, Division of General Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; sarahawl@umich.edu.

Steven J. Katz, Department of Internal Medicine, Division of General Medicine, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan; skatz@med.umich.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Janz NK, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of postmastectomy breast reconstruction: results from a population- based study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5325–5330. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kruper L, Holt A, Xu XX, et al. Disparities in reconstruction rates after mastectomy: patterns of care and factors associated with the use of breast reconstruction in Southern California. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:2158–2165. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1580-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Greenberg CC, Lipsitz SR, Hughes ME, et al. Institutional variation in the surgical treatment of breast cancer: a study of the NCCN. Ann Surg. 2011;254:339–345. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182263bb0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Waljee J, Mujahid M, Morrow M, Katz SJ. Understanding the impact of breast reconstruction on the surgical decision-making process for breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;112:489–494. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katz SJ, Hawley ST, Abrahamse P, et al. Does it matter where you go for breast surgery?: attending surgeon's influence on variation in receipt of mastectomy for breast cancer. Med Care. 2010;48:892–899. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181ef97df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lentol JR. Information and access to breast reconstructive surgery law. A. 10094-B/S.6693-B; Chapter 354; Health. New York State Assembly Committee on Codes: Annual Report. 2010;2010:12. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alderman AK, Hawley ST, Morrow M, et al. Receipt of delayed breast reconstruction after mastectomy: do women revisit the decision? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1748–1756. doi: 10.1245/s10434-010-1509-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamilton AS, Hofer TP, Hawley ST, et al. Latinas and breast cancer outcomes: population-based sampling, ethnic identity, and acculturation assessment. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2022–2029. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, et al. Decision involvement and receipt of mastectomy among racially and ethnically diverse breast cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1337–1347. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dillman DA. Mail and telephone surveys: the total design method. Wiley; New York: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greene FL, Page DL, Flemming ID, et al. American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. 6th Edition Springer; Philadelphia: 2002. pp. 233–240. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groves RM, Fowler FJ, Couper MP, Lepkowski JM, Singer E, Tourangeau R. Survey Methodology. Second Edition John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morrow M, Mujahid M, Lantz PM, et al. Correlates of breast reconstruction: results from a population-based study. Cancer. 2005;104:2340–2346. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Pusic AL, et al. The influence of sociodemographic factors and hospital characteristics on the method of breast reconstruction, including microsurgery: a U.S. population-based study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1071–1079. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e31824a29c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaplan CP, Karliner LS, Hwang ES, et al. The effect of system-level access factors on receipt of reconstruction among Latina and white women with DCIS. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;129:909–917. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1524-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morrow M, Jagsi R, Alderman AK, et al. Surgeon recommendations and receipt of mastectomy for treatment of breast cancer. JAMA. 2009;302:1551–1556. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tseng JF, Kronowitz SJ, Sun CC, et al. The effect of ethnicity on immediate reconstruction rates after mastectomy for breast cancer. Cancer. 2004;101:1514–1523. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bezuhly M, Temple C, Sigurdson LJ, Davis RB, Flowerdew G, Cook EF., Jr. Immediate postmastectomy reconstruction is associated with improved breast cancer-specific survival: evidence and new challenges from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database. Cancer. 2009;115:4648–4654. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksen C, Frisell J, Wickman M, Lidbrink E, Krawiec K, Sandelin K. Immediate reconstruction with implants in women with invasive breast cancer does not affect oncological safety in a matched cohort study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;127:439–446. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1437-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McCarthy CM, Pusic AL, Sclafani L, et al. Breast cancer recurrence following prosthetic, postmastectomy reconstruction: incidence, detection, and treatment. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:381–388. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000298316.74743.dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddy S, Colakoglu S, Curtis MS, et al. Breast cancer recurrence following postmastectomy reconstruction compared to mastectomy with no reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2011;66:466–471. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318214e575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosson GD, Singh NK, Ahuja N, Jacobs LK, Chang DC. Multilevel analysis of the impact of community vs patient factors on access to immediate breast reconstruction following mastectomy in Maryland. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1076–1081. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1076. discusion 1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]