Abstract

Tanshinone IIA (TSA) is a widely used traditional Chinese medicine, which has been demonstrated to protect damaged liver cells and is currently administered in the treatment of liver fibrosis. Liver precursor cells, also termed oval cells, are key in the repair of liver tissues following injury. However, whether TSA improves the function of liver cells and protects the liver from injury by enhancing the growth and proliferation of hepatic oval cells remains to be elucidated. In the present study, low to moderate concentrations of TSA were observed to stimulate proliferation, did not induce apoptosis in WB-F344 rat hepatic oval cells and the increased expression levels of β-catenin. WB-F344 cells were treated with various concentrations of TSA (0–80 µg/ml) for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Cell proliferation was measured using a Cell Counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay, a 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine assay and a carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay. The CCK-8 assay demonstrated that treatment of WB-F344 cells with 20–40 µg/ml TSA for up to 72 h significantly increased proliferation. Similar results were observed in the subsequent EdU and CFSE assays. Furthermore, a terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling assay demonstrated that 20–40 µg/ml TSA treatment for up to 96 h did not induce apoptosis of the WB-F344 cells. Notably, the results of western blot, immunofluorescence and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction analyses demonstrated that treatment of the WB-F344 cells with 20–40 µg/ml TSA for up to 72 h significantly increased the expression levels of β-catenin. These data indicated that TSA at concentrations between 20 and 40 µg/ml may induce WB-F344 cell proliferation by activating the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. The results of the present study suggest that TSA may be a useful natural agent to enhance repair and regeneration of the injured liver, and improve liver regeneration following orthotopic liver transplantation.

Keywords: tanshinone IIA, hepatic oval cells, cell proliferation, cell apoptosis, β-catenin

Introduction

The liver may be exposed to various harmful factors, which result in an inflammatory response, including viruses, certain medicines, self-immunity and alcohol consumption (1). Severe injury may result in liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, however, the liver has a regenerative capacity, and liver cells proliferate in response to various types of damage (2,3). Liver precursor cells, also termed oval cells, are key in the repair of liver tissue following injury (4). Following severe injury, hepatic oval cells proliferate and differentiate into several lineages, including biliary epithelia cells, hepatocytes, intestinal epithelial cells and, possibly, exocrine pancreas cells (5–8). Therefore, preservation of hepatic oval cells by natural products is a promising strategy for the prevention and treatment of liver diseases.

Tanshinone IIA (TSA) is an extract from the sage plant, Salvia miltiorrhiza, which was previously found to protect rat livers from fibrosis by promoting the apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells (9,10). TSA has also been demonstrated to improve liver function by inhibiting the activation of hepatic stellate cells, reducing the production of extracellular matrix and protecting hepatocytes (11,12). However, whether TSA improves the function of the liver, or protects the liver from injury by modulating the biology of hepatic oval cells, remains to be elucidated.

The molecular pharmacology of the protective effect of TSA on the liver is also unknown. Wnt signaling is important in the regulation of growth of various cell types, and in the maintenance and differentiation of stem cells. Notably, Wnt signaling is required for tissue repair and regeneration (13–15). β-catenin is a key downstream component in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, and regulates liver cell proliferation (16). Therefore, TSA may protect the liver via activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway.

The present study aimed to investigate the effects of TSA on the growth, proliferation and survival of hepatic oval cells, and examine the activity of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in hepatic oval cells following TSA treatment. The study may provide a novel treatment option in future, for patients with liver disease.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

The WB-F344 rat hepatic oval cell line was obtained from the Beijing Institute of Transfusion Medicine (Beijing, China), and is a cell line, which has been widely used in previous studies (13,14). The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium/Ham's F12 (DMEM/F12; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 0.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. TSA was obtained from Xi'an Haoxuan Bio-technique, Co., Ltd. (Xi'an, China).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

The WB-F344 cells were seeded into 96-well culture plates (5×103 cells/well). After 6 h, increasing doses of TSA were administered to the cells (10, 20, 40, 60 and 80 µg/ml). At 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, 10 µl CCK-8 reagent (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Inc., Kumamoto, Japan) was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. Absorbance values at a wavelength of 450 nm were recorded using a microplate reader (SpectraMax 250; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Viability (%) was calculated based on the optical density (OD) values, as follows: (OD of TSA treated sample - blank) / (OD of control sample - blank) ×100.

5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) incorporation assay

The cells were cultured on coverslips in 24-well plates (2×104 cells/well) and stimulated with TSA. After 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, the cells were treated with 50 µM EdU (Guangzhou RiboBio, Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) for an additional 2 h at 37°C. Following treatment, the culture medium was discarded and the cells were washed twice with Hyclone phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Logan, UT, USA). The cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde (Beijing Zhongyuan Huadun Technology Trade Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 30 min, followed by addition of 200 µl glycine (2 mg/ml; Amresco, LLC, Solon, OH, USA) to each well. After 5 min, the cells were washed twice with PBS and incubated with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) for 10 min at room temperature. Following washing with PBS for 5 min, 1X Apollo reaction reagent (Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) was added (200 µl/well) and the plates were incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 min, following which the cells were stained with 200 µl Hoechst 33342 (5 µg/ml; Guangzhou RiboBio Co., Ltd.) for an additional 30 min in the dark. Subsequent to washing with PBS twice, the cells were analyzed using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (TCS SP5; Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany).

Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) assay

The cells, at a concentration of ~106 cells/ml, were suspended in 4°C PBS and treated with CFSE (1:1,000; Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The cells were agitated gently for 5 min in the dark, followed by addition of FBS to a final concentration of 10%. Following centrifugation at 80 × g for 5 min, the supernatant was discarded. The cells were resuspended in DMEM/F12 culture medium, with 10% FBS, and plated in 6-well plates (106 cells/well). After 6 h, the cells were treated with various concentrations of TSA and, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h following treatment, the cells were trypsinized (Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) from the plates, centrifuged at 80 × g for 5 min, fixed with 4% formaldehyde (500 µl/well) for 30 min at room temperature, and analyzed by flow cytometry using a 488 nm argon-ion laser (BD FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Western blot analysis

The total proteins were extracted from cells using radioimmunoprecipitation assay lysis buffer (Merck Millipore, Dermstadt, Germany), containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% deoxycholate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride and 1 µg/ml protease cocktail). The concentration of the total protein was determined using a Micro BCA™ Protein Assay kit (Pierce; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Protein samples (60 µg/lane) were separated by 10% SDS-PAGE (Amresco, LLC) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). The membranes were then blocked with 5% w/v non-fat dried milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline and 0.1% Tween-20, pH 8.3 (TBST; Hyclone; GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at room temperature for 1 h. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. The primary antibodies used were as follows: Rabbit polyclonal anti-rat β-catenin (1:400; cat. no. BS3603; Bioworld Technology, Inc., St. Louis Park, MN, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-rat β-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. A5441; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Antigens were retrieved for 5 min in a microwave at high power followed by 13 min at mid-low power in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6.0). The membranes were subsequently washed with TBST for 15 min and incubated with the corresponding horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies at room temperature for 1 h: Goat monoclonal anti-rabbit Single Domain Antibody (0.05 µg/ml; cat. no. ab191866; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) and mouse monoclonal anti-actin (1:2,000; cat. no. ab3280). The immunoreactive bands were visualized using an ECL reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Protein band intensities were quantified using Quantity One® software (version 4.62; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining

WB-F344 cells were cultured until they reached 70% confluency in glass-bottom microwell dishes (MatTek Corporation, Ashland, MA, USA), fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Nanjing Oriental Pearl Industry & Trade Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and incubated with the β-catenin antibody (1:50) following permeabilization with 0.2% Triton-X-100. All images were taken using a laser-scanning microscope (FV1000; Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from cells using RNAiso Plus (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Dalian, China). Total RNA (1 µg) was reverse transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using a PrimeScript™ RT reagent kit (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.). RT-qPCR was performed for β-catenin and β-actin using SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's protocol. The primers (Beijing SBS Genetech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) used were as follows: Sense 5′-GCCAGTGGATTCCGTACTGT-3′ and anti-sense 5′-GAGCTTGCTTTCCTGATTGC-3′ for β-catenin; and sense 5′-TCAGGTCATCACTATCGGCAAT-3′ and antisense 5′-AAAGAAAGGGTGTAAAACGCA-3′ for β-actin. Reactions were performed in triplicate on an ABI PRISM® 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using the following conditions: 95°C for 30 sec; followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec; 60°C for 34 sec; a dissociation program of 95°C for 15 sec; 60°C for 60 sec; 95°C for 30 sec; and 60°C for 15 sec. β-actin served as an internal control, and melting curve analysis was performed to ensure that only one PCR product was formed. The relative quantity of RNA was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCq method (17).

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay

The WB-F344 cells (cultured on cover slips in 24-well plates at a density of 2×104 cells per well) were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized by 0.1% Triton X-100, treated with TUNEL reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Haimen, China) and incubated in the dark for 30 min at room temperature. Images were captured using an FV1000 laser-scanning microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The cell nuclei, which were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) and DAPI, indicated apoptotic cells. The percentage of TUNEL-positive cells in the total cell population was quantitated to assess the apoptotic index (18).

Statistical analysis

All results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation and were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference. Each experiment was repeated at least three times, and representative graphs are presented.

Results

TSA promotes the proliferation of WB-F344 hepatic oval cells

To determine the effects of TSA on the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells, the cells were treated with 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80 µg/ml TSA for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, and cell proliferation was analyzed using CCK-8, EdU and CFSE assays. The percentages of cell viability, indicated by CCK-8 are listed in Table I. At 10 µg/ml, TSA did not affect cell proliferation at any of the four time points assayed. By contrast, 20 µg/ml TSA stimulated oval cell proliferation within 72 h, particularly at the 48 h time point. At 40 µg/ml, TSA stimulated oval cell proliferation at each time point, with the percentage of proliferation at 48 h higher, compared with the percentages at 72 and 96 h. Treatment with 60 and 80 µg/ml TSA resulted in loss of cell viability at each time point. Thus, treatment with moderate concentrations of TSA (20–40 µg/ml) for 48–72 h promoted the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells, whereas higher concentrations of TSA (60–80 µg/ml) inhibited the proliferation of the WB-F344 oval cells.

Table I.

Concentration- and time-dependent effects of TSA on WB-F344 hepatic oval cell viability.

| Time-point (h) | Cell viability (%)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 µg/ml TSA | 20 µg/ml TSA | 40 µg/ml TSA | 60 µg/ml TSA | 80 µg/ml TSA | |

| 24 | 97±1.82 | 122±3.41a | 140±6.42a | 98±3.80 | 80±3.10a |

| 48 | 103±1.92 | 126±1.82a | 138±1.31a | 101±0.97 | 65±0.87a |

| 72 | 105±2.01 | 118±1.66b | 116±1.62b | 90±1.10b | 70±0.86a |

| 96 | 103±1.01 | 105±1.18 | 109±0.99b | 91±0.89b | 71±0.67a |

WB-F344 hepatic oval cells were treated with 10, 20, 40, 60 and 80 µg/ml TSA for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Cell viability was assessed using a Cell Counting kit-8 assay. The percentage of cell viability was determined and the results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation.

P<0.01 and

P<0.05 vs. control (0 µg/ml TSA) at each time-point. TSA, tanshinone IIA.

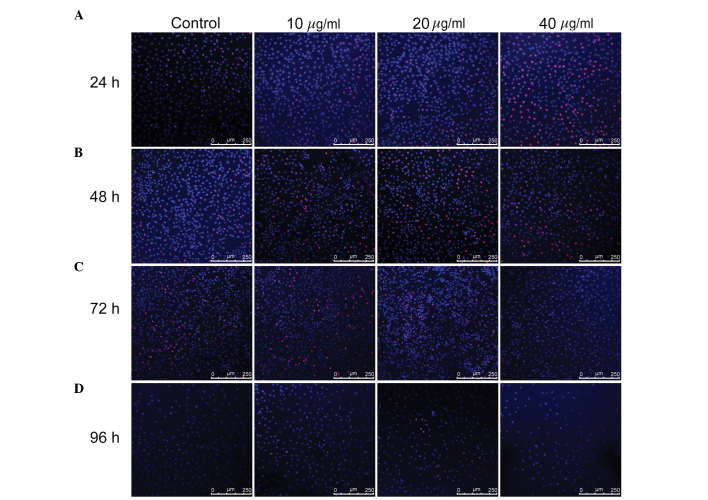

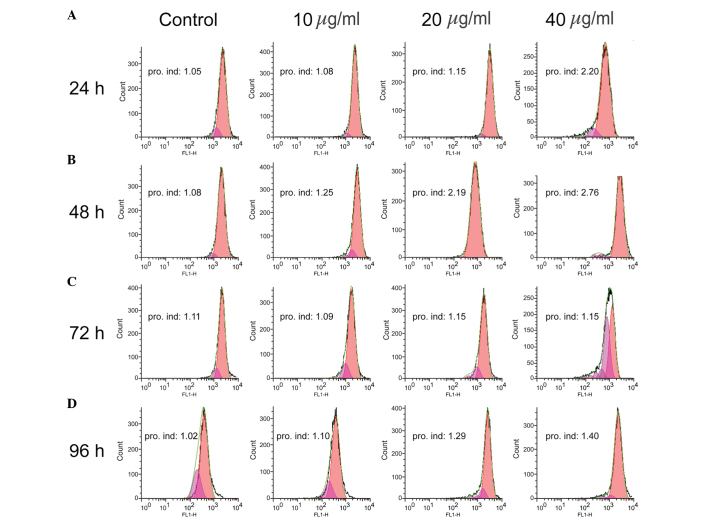

According to the results of the CCK-8 assay, the WB-F344 oval cells were subsequently treated with 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA for 24–96 h, and EdU and CFSE assays were performed. The EdU assay demonstrated that all three concentrations of TSA promoted cell proliferation within 72 h, particularly in the 40 µg/ml group at 24 h, the 20 µg/ml group at 48 h and the 10 µg/ml group at 72 h. At 96 h, the differences between the TSA-treated groups and control group were apparent, however they were not as marked as at 24, 48 and 72 h (Fig. 1). The proliferation index values of the WB-F344 oval cells were obtained from CFSE assays (Fig. 2). In the 40 µg/ml group, the proliferation index value was markedly higher than the other groups at each time-point. However, the 10 and 20 µg/ml TSA groups also exhibited higher proliferation indices than the untreated control group at 24, 48 and 96 h. At 72 h, the proliferation indices for the 10 µg/ml group was comparable with the control group, however, this result was not consistent with the data from the CCK-8 and EdU assays. At the 48 h time-point, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA were found to stimulate cell proliferation, compared with the control and 10 µg/ml TSA groups. After 72 h, the proliferation indices for all the three concentrations were similar to those in the 24 and 48 h time-points, with no significant differences between these three groups. After 96 h, the proliferation index values in groups administered TSA were higher than that of the control group, particularly in the 40 µg/ml group. The results from the present study demonstrated that 20–40 µg/ml TSA promoted the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells.

Figure 1.

Administration of TSA for 24–48 h promotes the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells. The WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed following (A) 24, (B) 48, (C) 72 and (D) 96 h. Magnification, ×40; scale bar, 250 µm. Cell proliferation was assessed by staining with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine and confirmed using confocal laser scanning microscopy. Proliferating cells are stained red. TSA, tanshinone IIA.

Figure 2.

TSA increases the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells. The WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed following (A) 24, (B) 48, (C) 72 and (D) 96 h. The cell proliferation index was assessed using a carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester assay coupled with flow cytometry. Representative histograms of cell proliferation were generated for WB-F344 hepatic oval cells treated with various concentrations of TSA (indicated in the panels). The proliferate index, relative to the control group, is indicated in each panel. TSA, tanshinone IIA; pro. ind, proliferative index.

TSA does not induce apoptosis of WB-F344 hepatic oval cells

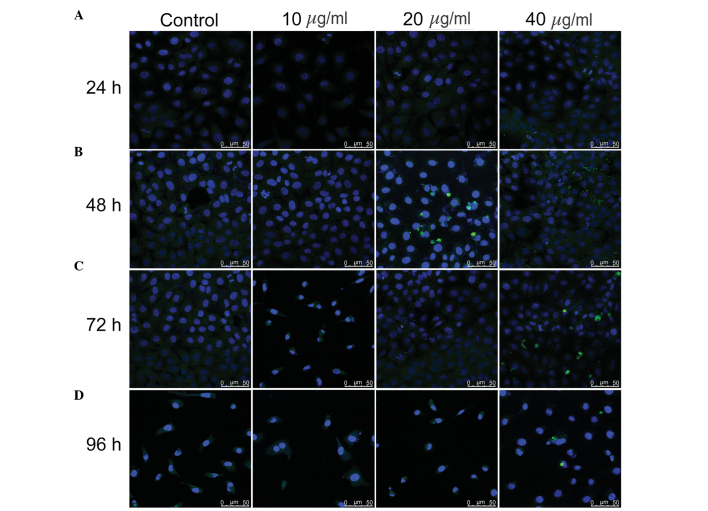

It was previously reported that TSA induces the apoptosis of rat hepatic stellate cells (9,10). To assess whether TSA induces apoptosis of hepatic oval cells, the WB-F344 cells were treated with 10, 20, and 40 µg/ml TSA for 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, and cellular apoptosis was determined using a TUNEL assay (Fig. 3). No TUNEL-positive cells, indicated by FITC and DAPI staining in the cell nucleus, were observed in the untreated control group or TSA-treated groups at any time point, suggesting that treatment with TSA up to 40 µg/ml does not induce apoptosis of WB-F344 hepatic oval cells.

Figure 3.

TSA fails to induce apoptosis in WB-F344 hepatic oval cells. The WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed following (A) 24, (B) 48, (C) 72 and (D) 96 h. Magnification, ×600; scale bar, 50 µm. Apoptosis was assessed using a TUNEL assay and confocal laser scanning microscopy was used to detect the TUNEL-positive cells. Apoptotic cells show fluorescein isothiocyanate (green) and DAPI (blue) nuclear staining. TSA, tanshinone IIA; TUNEL, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling.

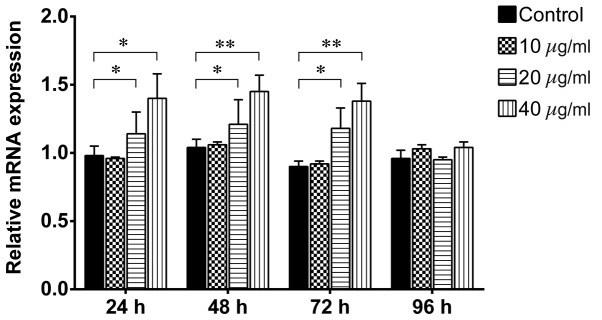

TSA increases the expression levels of β-catenin in WB-F344 oval cells

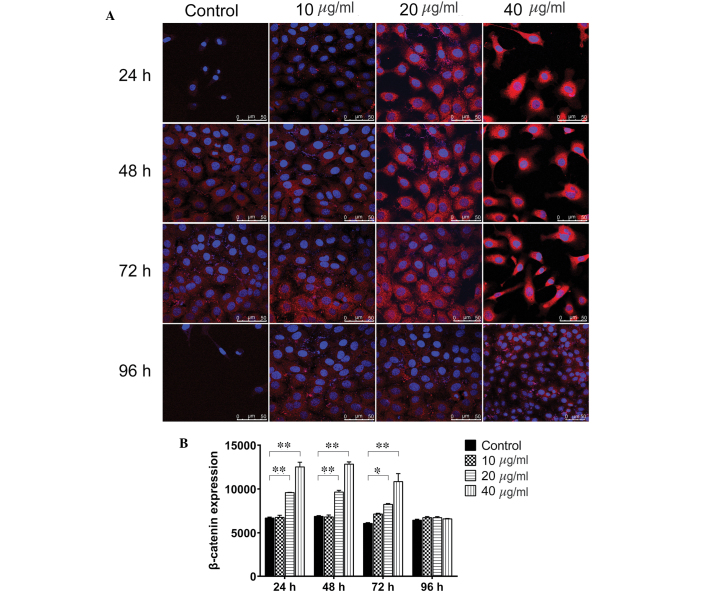

β-catenin is a key component in the canonical Wnt signaling pathway and has been demonstrated to regulate liver cell proliferation (16). To investigate whether TSA promotes the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells via activating Wnt/β-catenin signaling, the WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA, and the expression levels of β-catenin were assayed using western blotting, immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR analysis. As shown in Fig. 4, treatment of the WB-F344 oval cells with 20 µg/ml TSA for 24, 48 and 72 h significantly increased the protein levels of β-catenin (P=0.0313, P=0.0359 and P=0.0390, respectively). Similarly, treatment of the WB-F344 oval cells with 40 µg/ml TSA for 24, 48 and 72 h significantly upregulated the protein expression levels of β-catenin (P=0.0202, P=0.0063 and P=0.0071, respectively). However, no differences were observed between the control group and the TSA groups at 96 h (P>0.05). Immunofluorescence staining (Fig. 5) indicated that 20 µg/ml TSA significantly upregulated β-catenin at the 24, 48 and 72 h time points (P=0.0006, P=0.0005 and P=0.0243, respectively), as did 40 µg/ml TSA (P=0.0004, P=0.0003 and P=0.0098, respectively). After 96 h, neither 20 nor 40 µg/ml TSA altered the expression levels of β-catenin (P>0.05). Consistent with the upregulation in the protein expression levels of β-catenin, the RT-qPCR analysis demonstrated that treatment with 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA for 24–72 h significantly increased the mRNA expression levels of β-catenin (Fig. 6). However, 10 µg/ml TSA did not alter the mRNA expression levels at any time point, and TSA did not affect the mRNA level of β-catenin after 96 h at any concentration (P>0.05). These results indicated that activation of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway is one of the underlying molecular mechanisms by which TSA enhances the proliferation of hepatic oval cells.

Figure 4.

TSA increases the protein expression levels of β-catenin in WB-F344 oval cells. The WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed following 24–96 h. Total proteins were extracted for (A) immunoblotting of β-catenin and β-actin. (B) Relative protein levels of β-catenin were normalized to β-actin. Data are expressed as the mean standard deviation. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. control. TSA, tanshinone IIA.

Figure 5.

TSA upregulates the protein expression levels of β-catenin in WB-F344 oval cells. (A) WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed after 24–96 h. Immunofluorescence was used to assess the expression β-catenin (red). Cell nuclei were counter-stained blue with DAPI. Magnification, ×600; scale bar, 50 µm. (B) Number of β-catenin-positive stained cells in five randomly-selected fields were counted and plotted. Data are expressed as the mean standard deviation. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. control. TSA, tanshinone IIA.

Figure 6.

TSA upregulates the mRNA expression of β-catenin in hepatic cells. The WB-F344 oval cells were treated with 0 (control), 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA and analyzed following 24–96 h. Total RNAs were extracted for reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. β-catenin served as an internal control. Data are expressed as the mean standard deviation. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01, vs. control. TSA, tanshinone IIA; mRNA, messenger RNA.

Discussion

In the present study, it was demonstrated that TSA promoted the proliferation of WB-F344 hepatic oval cells. Notably, TSA was observed to upregulate the expression levels of β-catenin in the WB-F344 oval cells. These results suggested that activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is one of the mechanisms by which TSA enhances the proliferation of hepatic oval cells and protects the liver against injury.

Hepatic progenitor cells, also termed oval cells, proliferate and differentiate into hepatocytes and biliary epithelial cells following stimulation, including viral infection and cytotoxic drugs. It has been suggested that hepatic oval cells facilitate liver regeneration following orthotopic liver transplantation (19). Previous studies have demonstrated that WB-F344 oval cells are important in the repair and regeneration of injured liver (3,20). Accordingly, the WB-F344 oval cell line is considered a hepatic stem cell line (11,21). Furthermore, hepatic oval cells retain progenitor cell features without spontaneous malignant transformation following prolonged cultivation, thus, the WB-F344 oval cell line may serve as an expandable cell source for future exploitation of stem cell technology (22).

Salvia miltiorrhiza is a plant whose roots have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for >2,000 years and has been shown to mediate concentration-dependent anti-fibrosis (23). TSA has been identified as one of the predominant extracts of Salvia miltiorrhiza, and clinical trials have demonstrated that TSA promotes blood circulation and improves cardiovascular disease (24,25), improves heart function by enhancing myocardial contractility, inhibits extracellular matrix deposition, and limits apoptosis by cardiomyocytes and oxidative damage (26). TSA also inhibits the proliferation of hepatic stellate cells through enhanced apoptosis, which is induced by stimulating the extracellular signal-regulated kinase-Bcl-2-associated X protein-caspase signaling pathways via the RAF proto-oncogene serine/threonine-protein kinase/prohibitin complex (9). A previous study demonstrated that TSA interacts with a non-classical estrogen receptor to maintain an appropriate balance between the net deposition of collagen and elastin, while providing optimal durability and resilience of newly deposited matrix (27). However, the effect of TSA on the growth, proliferation and survival of hepatic progenitor cells remains to be elucidated. In the present study, using CCK-8, EdU and CFSE assays, TSA was demonstrated to promote the proliferation of WB-F344 oval cells.

The results of the CCK-8 assay revealed that 10–40 µg/ml TSA significantly induced proliferation of the hepatic oval cells within 72 h of treatment, but not at 96 h post-treatment. However, higher concentrations of TSA (60–80 µg/ml) inhibited hepatic oval cell proliferation, which was readily observed 72 and 96 h following treatment, indicating that high concentrations of TSA were cytotoxic to the oval cells. Furthermore, the EdU assay indicated that 10–40 µg/ml TSA stimulated cell proliferation following treatment for 24 and 48 h, and the CFSE assay demonstrated that the cell proliferative index value of 10, 20 and 40 µg/ml TSA were higher than that of the control group at each time point assayed. These results were consistent with previous studies of different cell types, indicating that TSA induces or inhibits cell proliferation depending on the concentration of TSA administered (28–30). In addition, the TUNEL assay performed in the present study demonstrated that low concentrations of TSA (<40 µg/ml) had no stimulatory effect on hepatic oval cell apoptosis.

Previous studies have indicated that the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signaling pathways are upregulated in undifferentiated, proliferating and potentially migrating hepatic progenitor cells during severe progressive canine liver disease (31). Furthermore, the canonical Wnt signaling pathway was found to be key in regulating the proliferation and self-renewal of hepatic oval cells (1). In the present study, the expression levels of β-catenin in hepatic oval cells following treatment with various concentrations of TSA for different time periods was investigated using western blot, immunofluorescence and RT-qPCR analyses. β-catenin was significantly upregulated following treatment with 20–40 µg/ml TSA for 72 h. These results suggested that TSA may have activated the canonical Wnt signaling pathway, which stimulated proliferation of the hepatic oval cells.

In conclusion, the results of the present study indicated that TSA stimulated the proliferation of WB-F344 rat hepatic oval cells via activation of the canonical Wnt signaling pathway. These findings suggest that TSA treatment may promote the repair and regeneration of injured liver, or improve liver regeneration following orthotopic liver transplantation.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Medjaden Bioscience Limited (Hong Kong, China) for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

References

- 1.Zhang Y, Li XM, Zhang FK, Wang BE. Activation of canonical Wnt signaling pathway promotes proliferation and self-renewal of rat hepatic oval cell line WB-F344 in vitro. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:6673–6680. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.6673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lowes KN, Croager EJ, Olynyk JK, Abraham LJ, Yeoh GC. Oval cell-mediated liver regeneration: Role of cytokines and growth factors. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:4–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walkup MH, Gerber DA. Hepatic stem cells: In search of. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1833–1840. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber E. Similarities in the sequence of early histological changes induced in the liver of the rat by ethionine, 2-acety-lamino-fluorene, and 3′-methyl-4-dimethylaminoazobenzene. Cancer Res. 1956;16:142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thorgeirsson SS. Hepatic stem cells. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1331–1333. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fausto N. Oval cells and liver carcinogenesis: An analysis of cell lineages in hepatic tumors using oncogene transfection techniques. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1990;331:325–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sell S. Is there a liver stem cell? Cancer Res. 1990;50:3811–3815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigal SH, Brill S, Fiorino AS, Reid LM. The liver as a stem cell and lineage system. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:G139–G148. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.2.G139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan TL, Wang PW. Explore the molecular mechanism of apoptosis induced by tanshinone IIA on activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:734987. doi: 10.1155/2012/734987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Che XH, Park EJ, Zhao YZ, Kim WH, Sohn DH. Tanshinone II A induces apoptosis and S phase cell cycle arrest in activated rat hepatic stellate cells. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2010;106:30–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niu XH, Hua HY, Guo WJ, Zhang Y, Liu M, Hong Y, Wu PF, Lu P, Zhang HF. Clinical efficiency of tanshinone IIA-sulfonate in treatment of liver fibrosis of advanced schistosomiasis. Zhongguo Xue Xi Chong Bing Fang Zhi Za Zhi. 2013;25:137–140. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sun RF, Liu LX, Zhang HY. Effect of tanshinone II on hepatic fibrosis in mice. Zhongguo Zhong Xi Yi Jie He Za Zhi. 2009;29:1012–1017. In Chinese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clevers H, Loh KM, Nusse R. Stem cell signaling. An integral program for tissue renewal and regeneration: Wnt signaling and stem cell control. Science. 2014;346:1248012. doi: 10.1126/science.1248012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, Yates JR, III, Nusse R. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature01611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reis M, Liebner S. Wnt signaling in the vasculature. Exp Cell Res. 2013;319:1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Micsenyi A, Tan X, Sneddon T, Luo JH, Michalopoulos GK, Monga SP. Beta-catenin is temporally regulated during normal liver development. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1134–1146. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pan L, Shi X, Liu S, Guo X, Zhao M, Cai R, Sun G. Fluoride promotes osteoblastic differentiation through canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Toxicol Lett. 2014;225:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2013.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saraste A, Arola A, Vuorinen T, Kytö V, Kallajoki M, Pulkki K, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Hyypiä T. Cardiomyocyte apoptosis in experimental coxsackievirus B3 myocarditis. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2003;12:255–262. doi: 10.1016/S1054-8807(03)00077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Z, Chen J, Li L, Ran JH, Liu J, Gao TX, Guo BY, Li XH, Liu ZH, Liu GJ, et al. In vitro proliferation and differentiation of hepatic oval cells and their potential capacity for intrahepatic transplantation. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46:681–688. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dezső K, Papp V, Bugyik E, Hegyesi H, Sáfrány G, Bödör C, Nagy P, Paku S. Structural analysis of oval-cell-mediated liver regeneration in rats. Hepatology. 2012;56:1457–1467. doi: 10.1002/hep.25713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li WQ, Li YM, Guo J, Liu YM, Yang XQ, Ge HJ, Xu Y, Liu HM, He J, Yu HY. Hepatocytic precursor (stem-like) WB-F344 cells reduce tumorigenicity of hepatoma CBRH-7919 cells via TGF-beta/Smad pathway. Oncol Rep. 2010;23:1601–1607. doi: 10.3892/or_00000801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang P, Cong M, Liu TH, Yang AT, Cong R, Wu P, Tang SZ, Xu Y, Wang H, Wang BE, et al. Primary isolated hepatic oval cells maintain progenitor cell phenotypes after two-year prolonged cultivation. J Hepatol. 2010;53:863–871. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin YL, Hsu YC, Chiu YT, Huang YT. Antifibrotic effects of a herbal combination regimen on hepatic fibrotic rats. Phytother Res. 2008;22:69–76. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang H, Long M, Wu Z, Han X, Yu Y. Sodium tanshinone IIA silate as an add-on therapy in patients with unstable angina pectoris. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:1794–1799. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.12.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mao S, Wang L, Zhao X, Shang H, Zhang M, Hinek A. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate for reduction of periprocedural myocardial injury during percutaneous coronary intervention (STAMP trial): Rationale and design. Int J Cardiol. 2015;182:329–333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.12.166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pang H, Han B, Yu T, Peng Z. The complex regulation of tanshinone IIA in rats with hypertension-induced left ventricular hypertrophy. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 27.Mao S, Wang Y, Zhang M, Hinek A. Phytoestrogen, tanshinone IIA diminishes collagen deposition and stimulates new elastogenesis in cultures of human cardiac fibroblasts. Exp Cell Res. 2014;323:189–197. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yu Q, Chen H, Sheng L, Liang Y, Li Q. Sodium tanshinone IIA sulfonate prolongs the survival of skin allografts by inhibiting inflammatory cell infiltration and T cell proliferation. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;22:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang L, Guo H, Dong L, Wang L, Liu C, Wang X. Tanshinone IIA inhibits the growth, attenuates the stemness and induces the apoptosis of human glioma stem cells. Oncol Rep. 2014;32:1303–1311. doi: 10.3892/or.2014.3293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shan QQ, Guo Y, Gong YP. Effect of tanshinone II A on leukemia cell line K562. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2014;45:410–413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schotanus BA, Kruitwagen HS, van den Ingh TS, van Wolferen ME, Rothuizen J, Penning LC, Spee B. Enhanced Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling in the activated canine hepatic progenitor cell niche. BMC Vet Res. 2014;10:309. doi: 10.1186/s12917-014-0309-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]