Abstract

A variety of substituted indoles and benzofurans are accessed via a platinum catalyzed annulation and vinylogous addition of enol nucleophiles. Several β-dicarbonyl compounds participate in the reaction, as do α-nitro and α-cyano carbonyl species. Subjecting the indole products to acidic conditions results in the formation of fused heterocycles.

Substituted indoles continue to prove their worth as privileged molecules. This structural motif is present in a wide variety of natural products and pharmaceuticals,1 and its utility as an important chemical building block is highlighted by the rich chemistry describing its elaboration to more complex molecular architectures.2 Numerous approaches have been developed over the years to facilitate indole formation,3 with many recent efforts utilizing metal catalysis to promote the ring formation.4 Among these, methods that use indole formation as part of a multicomponent coupling process are particularly appealing due to their ability to synchronize the formation of multiple bonds during a single reaction.5

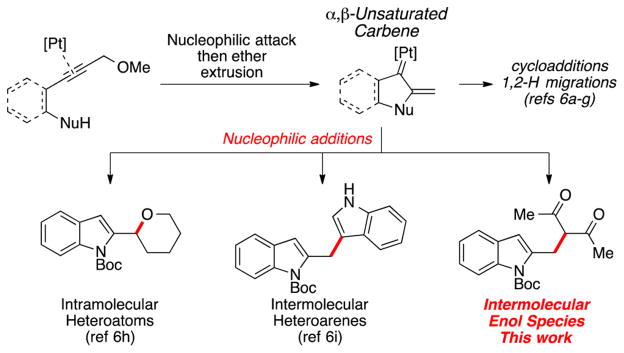

We envisioned a process where initial indole formation would be linked to the intermolecular addition of a carbon nucleophile, providing ready access to diversely substituted heterocyclic products. We and others have been investigating the use of platinum catalysis to generate α,β-unsaturated carbene intermediates via an intramolecular nucleophilic addition into alkynes bearing propargylic ethers (Scheme 1).6 These carbenes have been demonstrated to undergo cyclo-additions,6a–d hydrogen migrations,6e–g and vinylogous nucleophilic additions.6h,i In the latter systems, both heteroatom nucleophiles and electron-rich heterocycles have been shown to be competent reactants. Inspired by the demonstration that enol nucleophiles can achieve vinylogous additions into rhodium and gold carbenes generated from diazo species,7 we became curious whether this class of nucleophiles would be participatory within this catalytic platinum reaction manifold. Herein, we demonstrate that the nucleophilic interception by these enol species can indeed be coupled to indole formation, yielding heterocyclic products that feature synthetically attractive structural motifs (e.g., all-carbon quaternary carbon centers, functionality poised for subsequent manipulations).

Scheme 1.

α,β-Unsaturated Carbene Generation/Nucleophilic Attack

We began our studies using N-Boc-aniline 1a and 3-ethyl-2,4-pentanedione as our enol nucleophile (Table 1). Using similar conditions to those we had developed for the vicinal bisheterocyclizations, we observed minimal nucleophilic addition (entry 1, 8% yield of 3aa). We suspected that the poor reactivity was due to the PPh3 ligand rendering the metal carbene too electron rich to induce the double-addition process. Indeed, switching the phosphine ligand to P(C6F5)3 produced the desired reactivity, generating indole 3aa in 58% yield (entry 2). Added base suppressed the reaction (entries 3 and 4), but several Lewis acid additives were beneficial to the overall process. Given its boost in reactivity and relatively low cost, we determined MgCl2 was the optimal Lewis acid for further studies. Reducing the equivalents of enol source to 2.0 or 1.1 resulted in diminished reactivity (entries 10 and 11). Interestingly, exclusion of the phosphine ligand had no adverse effect on the reaction overall (entry 12), suggesting that the phosphine was merely an inhibitor when electron rich and not influential when electron deficient. Other Lewis acids without phosphine additives showed comparable results (entries 13–14). As a control experiment, we also ran the reaction without a Lewis acid and observed a measurable decrease in yield (entry 15), confirming our hypothesis that the efficiency of the addition process is loosely correlated to the concentration of the enol nucleophile.8,9

Table 1.

Optimization of the Reaction Conditions

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | ligand | additive (mol %) | time (h) | yield 3aaa (%) |

| 1 | PPh3 | none | 5 | 8 |

| 2 | P(C6F5)3 | none | 3 | 58 |

| 3 | P(C6F5)3 | Na2CO3 (100) | 5 | 0 |

| 4 | P(C6F5)3 | Na2CO3 (10) | 5 | 18 |

| 5 | P(C6F5)3 | MgCl2 (5) | 2 | 72 |

| 6 | P(C6F5)3 | La(OTf)3 (5) | 2 | 73 |

| 7 | P(C6F5)3 | CuSO4 (10) | 4 | 68 |

| 8 | P(C6F5)3 | CeCl3 (5) | 0.5 | 65 |

| 9 | P(C6F5)3 | Sc(OTf)3 (5) | 0.5 | 30 |

| 10 | P(C6F5)3 | MgCl2 (5) | 2 | 50b |

| 11 | P(C6F5)3 | MgCl2 (5) | 2 | 30c |

| 12 | none | MgCl2 (5) | 3 | 72 (70)d |

| 13 | none | CuSO4 (20) | 6 | 61 |

| 14 | none | La(OTf)3 (5) | 2 | 71 |

| 15 | none | none | 2 | 59 |

Determined by 1H NMR using dibenzyl ether as an internal standard.

Used 2.0 equiv of diketone 2a.

Used 1.1 equiv of diketone 2a.

Isolated yield in parentheses.

With the optimized conditions in hand (2.5 mol % Zeise’s dimer, 5 mol % MgCl2, no ligand), we set out to establish the generality of this reaction. A variety of β-dicarbonyl compounds were evaluated using N-Boc aniline 1a as our carbene precursor (Scheme 2). Overall, this process generated the desired substituted indoles in high yields. β-Diketones, ketoesters, and ketoamides all successfully added into the platinum carbene intermediate. The nucleophile stoichiometry could be reduced, albeit generating indole 3ac in lower relative yield and requiring longer reaction times (75% in 10 h with 1.1 equiv vs 89% in 3 h with 5 equiv). α-Nitro carbonyl compounds proved to be competent nucleophiles, forming indoles 3af and 3ag in good yields. Of particular interest is indole 3ag, which represents a modular method of constructing an isomeric tryptophan motif with the side chain connected to the 2-position of the indole ring.10 Similar to the product formed in reaction optimization (3aa), nucleophiles with an additional α-substituent could be utilized in this transformation to generate the formation of all-carbon quaternary centers (3ah–aj). Nucleophiles that form less of the enol species in equilibrium (malonates, ketonitriles) were less reactive in this catalytic manifold.

Scheme 2. Examination of Enol Nucleophiles on the Coupled Annulation/Vinylogous Addition Reaction.

aUsing 1.0 equiv of methyl acetoacetate.

Having demonstrated a broad tolerance for a variety of enol nucleophiles, we next explored the effects of substitution on the carbene precursor (Scheme 3). The starting materials were easily accessed, generally via Sonogashira coupling of o-iodoanilines with the desired alkyne.11 Both acetyl- and toluenesulfonyl-protected anilines were successful (3bc and 3cc), although with lower yields than obtained when the corresponding N-Boc aniline was used. The presence of electron-withdrawing (–NO2) and electron-donating (–OMe) groups could be incorporated into the carbene precursor. Secondary propargylic ethers were also tolerated, forming indoles 3fc–ic in good yields; diastereoselectivity, however, was not controlled in this process. A variety of phenol substrates also reacted as hoped, generating benzofuran products 3jc, 3kc, and 3lc in good yields.

Scheme 3. Examination of Substitution on the Coupled Annulation/Vinylogous Addition Reactiona.

aDiastereoselectivity ranged from 1 to 2:1; see the Supporting Information for details. bStarting material is Me ether. cStarting material is Bn ether.

In our prior work,6h we had demonstrated that heteroatom nucleophiles could intramolecularly intercept the putative carbene intermediate at the β position. To evaluate the efficacy and the selectivity of the dicarbonyl nucleophile, we performed two tests (Scheme 4). In the first case, substrate 4 was combined with ketoester 2c under the catalytic conditions. Bisheterocycle 5 was the only observed product, illustrating that intramolecular trapping by the hydroxyl group was faster than dicarbonyl nucleophile incorporation. This experiment also agrees with our proposed mechanistic rationale, implicating the nucleophilic addition at the β position of a platinum carbene. An alternative mechanism involving addition to an indolyl cation that originates from ether ionization12 would suggest that compound 6 would be observed in the reaction via eventual conversion of 5. The second experiment represented a competition between two external nucleophiles. For this case, addition of the ketoester was completely selective, as only indole 3ac was observed.13

Scheme 4.

Nucleophile Competition Experiments

The coupling of a dicarbonyl group to an indole moiety with this relative connectivity enables direct routes to fused heterocyclic compounds. Illustrated in Scheme 5, indoles 3ac and 3ai were subjected to acidic conditions (CSA, toluene, heat). In the case of indole 3ac, Boc removal and condensation with the methyl ketone occurred to afford the pyrrolo[1,2-a]indole skeleton in compound 8 in good yield.14 This fused heterocyclic motif is of interest due to its structural relationship to the mitomycins.15 Indole 3ai, meanwhile, underwent an orthogonal ring closure at C3, and heterocycle 9 was formed.16 The straightforward conversion of the products that arise from these vinylogous carbene additions to higher order heterocycles is demonstrative of the overall utility of this method.

Scheme 5.

Elaboration of the Indole Products

Catalytic transition metal carbenes continue to be proven invaluable in synthetic chemistry due to their capacity to promote a variety of bond-forming reactions. The results described herein highlight the ability to generate platinum carbenes under mild conditions, enabling the intermolecular construction of carbon–carbon bonds with a variety of enol sources. The addition of Lewis acidic MgCl2 was important to encourage sufficient nucleophilicity across this range of enol species. The regioselectivity of addition to the putative vinyl platinum carbene intermediate parallels the observed vinylogous additions of nucleophiles in vinyl rhodium and gold carbenes.7 This reactivity mode offers an opportunity to introduce species β to the carbene center and represents a unique coupling process with concomitant ring closure. Further investigations into this reactivity profile and applications are underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The National Institutes of Health (NIGMS, R01GM110560) is gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.or-glett.5b03246.

Experimental procedures, compound characterization data, and spectra (PDF)

References

- 1.(a) Kaushik NK, Kaushik N, Attri P, Kumar N, Kim CH, Verma AK, Choi EH. Molecules. 2013;18:6620–6662. doi: 10.3390/molecules18066620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kochanowska-Karamyan A, Hamann MT. Chem Rev. 2010;110:4489–4497. doi: 10.1021/cr900211p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Somei M, Yamada F. Nat Prod Rep. 2005;22:73–103. doi: 10.1039/b316241a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Shiri M. Chem Rev. 2012;112:3508–3549. doi: 10.1021/cr2003954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bartoli G, Bencivenni G, Dalpozzo R. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:4449–4465. doi: 10.1039/b923063g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Cacchi S, Fabrizi G. Chem Rev. 2005;105:2873–2920. doi: 10.1021/cr040639b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Inman M, Moody CJ. Chem Sci. 2013;4:29–41. [Google Scholar]; (b) Taber DF, Tirunahari PK. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:7195–7210. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Humphrey GR, Kuethe JT. Chem Rev. 2006;106:2875–2911. doi: 10.1021/cr0505270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kothandaraman P, Rao W, Foo SJ, Chan PWH. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:4619–4623. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Gao J, Shao Y, Zhu J, Zhu J, Mao H, Wang X, Lv X. J Org Chem. 2014;79:9000–9008. doi: 10.1021/jo501250u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Guo T, Huang F, Yu L, Yu Z. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:296–302. [Google Scholar]; (d) Zoller J, Fabry DC, Ronge MA, Rueping M. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:13264–13268. doi: 10.1002/anie.201405478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Vaswani RG, Albrecht BK, Audia JE, Côté; Dakin LA, Duplessis M, Gehling VS, Harmange J–C, Hewitt MC, Leblanc Y, Nasveschuk CG, Taylor AM. Org Lett. 2014;16:4114–4117. doi: 10.1021/ol5018118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Rajagopal B, Chou C–H, Chung C–C, Lin P–C. Org Lett. 2014;16:3752–3755. doi: 10.1021/ol501618z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Matsuda T, Tomaru Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 2014;55:3302–3304. [Google Scholar]; (h) Dawande SG, Kanchupalli V, Kalepu J, Chennamsetti H, Lad BS, Katukojvala S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:4076–4080. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Jones C, Nguyen Q, Driver TG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:785–788. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Chikkade PK, Shimizu Y, Kanai M. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1585–1590. [Google Scholar]; (k) Li X, Song W, Tang W. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16797–16800. doi: 10.1021/ja408829y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (l) Liu B, Song C, Sun C, Zhou S, Zhu J. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:16625–16631. doi: 10.1021/ja408541c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (m) Cajaraville A, López S, Varela JA, Saá C. Org Lett. 2013;15:4576–4579. doi: 10.1021/ol402125t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (n) Piou T, Neuville L, Zhu J. Tetrahedron. 2013;69:4415–4420. [Google Scholar]; (o) Wang C, Sun H, Fang Y, Huang Y. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:5795–5798. doi: 10.1002/anie.201301742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Matcha K, Antonchick AP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:11960–11964. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hao W, Geng W, Zhang W–X, Xi Z. Chem - Eur J. 2014;20:2605–2612. doi: 10.1002/chem.201304215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Hu Z, Wang J, Liang D, Zhu Q. Adv Synth Catal. 2013;355:3290–3294. [Google Scholar]; (d) Barluenga J, Rodríguez F, Fañanás FJ. Chem - Asian J. 2009;4:1036–1048. doi: 10.1002/asia.200900018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Kaspar LT, Ackermann L. Tetrahedron. 2005;61:11311–11316. [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Saito K, Sogou H, Suga T, Kusama H, Iwasawa N. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:689–691. doi: 10.1021/ja108586d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shu D, Song W, Li X, Tang W. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:3237–3240. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kusama H, Sogo H, Saito K, Suga T, Iwasawa N. Synlett. 2013;24:1364–1370. [Google Scholar]; (d) Yang W, Wang T, Yu Y, Shi S, Zhang T, Hashmi ASK. Adv Synth Catal. 2013;355:1523–1528. [Google Scholar]; (e) Allegretti PA, Ferreira EM. Org Lett. 2011;13:5924–5927. doi: 10.1021/ol202649j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Allegretti PA, Ferreira EM. Chem Sci. 2013;4:1053–1058. [Google Scholar]; (g) Kwon Y, Kim I, Kim S. Org Lett. 2014;16:4936–4939. doi: 10.1021/ol502465e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Allegretti PA, Ferreira EM. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:17266–17269. doi: 10.1021/ja408957a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Shu D, Winston-McPherson GN, Song W, Tang W. Org Lett. 2013;15:4162–4165. doi: 10.1021/ol4018408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Davies HML, Hu B, Saikali E, Bruzinski PR. J Org Chem. 1994;59:4535–4541. [Google Scholar]; (b) Smith AG, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:18241–18244. doi: 10.1021/ja3092399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Valette D, Lian Y, Haydek JP, Hardcastle KI, Davies HML. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2012;51:8636–8639. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Briones JF, Davies HML. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:13314–13317. doi: 10.1021/ja407179c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Xu X, Zavalij PY, Hu W, Doyle MP. J Org Chem. 2013;78:1583–1588. doi: 10.1021/jo302696y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Guzmán PE, Lian Y, Davies HML. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2014;53:13083–13087. doi: 10.1002/anie.201406440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.For studies on the keto–enol equilibrium, see: Burdett JL, Rogers MT. J Am Chem Soc. 1964;86:2105–2109.Mills SG, Beak P. J Org Chem. 1985;50:1216–1224.

- 9.For a table with additional optimization reactions, see the Supporting Information.

- 10.For select syntheses and studies of “isotryptophan”, see: Ma C, Liu X, Li X, Flippen-Anderson J, Yu S, Cook JM. J Org Chem. 2001;66:4525–4542. doi: 10.1021/jo001679s.Carlier PR, Lam PC-H, Wong DM. J Org Chem. 2002;67:6256–6259. doi: 10.1021/jo025964i.

- 11.See the Supporting Information for details.

- 12.For examples of Lewis acid mediated indolyl cation formation and subsequent nucleophilic addition, see: Fu T–h, Bonaparte A, Martin SF. Tetrahedron Lett. 2009;50:3253–3257. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2009.02.018.Bhat V, Allan KM, Rawal VH. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5798–5801. doi: 10.1021/ja201834u.Feldman KS, Gonzalez IY, Glinkerman CM. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:15138–15141. doi: 10.1021/ja508421e.Zhong X, Qi S, Li Y, Zhang J, Han FS. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:3734–3740.

- 13.We believe this outcome simply illustrates that an enol nucleophile is faster at reacting with the metal carbene than an alcohol in an intermolecular sense. It likely does not indicate the necessity of an anionic/metal-complexed nucleophile, as demonstrated by the outcome in Table 1, entry 15.

- 14.For examples of this type of cyclization, see: Blay G, Fernández I, Pedro JR, Vila C. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:6731–6734.Sakamoto T, Itoh J, Mori K, Akiyama T. Org Biomol Chem. 2010;8:5448–5454. doi: 10.1039/c0ob00197j.

- 15.For reviews on mitomycin synthetic studies, see: Takahashi K, Kametani T. Heterocycles. 1979;13:411–467.Andrez JC. Beilstein J Org Chem. 2009;5:33. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.5.33.

- 16.We have not detected the products arising from the opposite regioselectivity of cyclization in either case. It is not clear a priori why cyclization selectivity occurs with N vs C3 preferences based on α-substitution. Potentially, the aromatization of compound 8 provides a thermodynamically favored tricycle that cannot be obtained using indole 3ai. Further investigations would be required to determine all of the factors that govern cyclization regioselectivity.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.