Abstract

Infections and inflammation can lead to cachexia and wasting of skeletal muscle and fat tissue by as yet poorly understood mechanisms. We observed that gut colonization of mice by a strain of Escherichia coli prevents wasting triggered by infections or physical damage to the intestine. During intestinal infection with the pathogen Salmonella Typhimurium or pneumonic infection with Burkholderia thailandensis, the presence of this E. coli did not alter changes in host metabolism, caloric uptake or inflammation, but instead sustained signaling of the IGF-1/PI3K/AKT pathway in skeletal muscle, required for prevention of muscle wasting. This effect was dependent on engagement of the NLRC4 inflammasome. Therefore, this commensal promotes tolerance to diverse diseases.

Infections and inflammation lead to profound metabolic alterations that are primarily driven by responses of muscle, fat and the liver (1, 2). Coupled with loss of appetite dysregulated metabolism can lead to the severe metabolic pathology called wasting syndrome (cachexia). Such wasting constitutes loss of skeletal muscle (with and without adipose tissue depletion) resulting in weight loss (2). Tuberculosis, sepsis and HIV, as well as inflammatory diseases including colitis (1, 3, 4), can trigger wasting. Wasting can also interferes with therapeutic interventions and causes untreatable morbidity and mortality (5).

Mammals have coevolved with a complex gut microbial community, the gut microbiome, and depend on the metabolic benefits that it confers on the host (6, 7). Here, we have investigated whether constituents of the microbiome have any protective effect during metabolic dysregulation caused by gut trauma and/or infection.

Intestinal injury and inflammation can cause muscle wasting and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and Crohn’s disease (CD) patients suffer from muscle wasting (8). Antibiotics cause ecological perturbations in the microbiota, (9) and coupling antibiotics with disease models can reveal how specific constituents of the microbiota impact disease. The dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) intestinal injury model is one of the best-studied models of IBD/CD-associated pathologies, including intestinal inflammation, mucus erosion and microbiota decompartmentalization (10). C57Bl/6 mice treated with DSS, exhibited muscle and fat wasting that was associated with anorexia, colonic inflammation and bloody, diarrhea (Fig 1A–B, S1). Administration of the broad-spectrum antibiotic cocktail Ampicillin, Vancomycin, Neomycin and Metronidazole (AVNM) had no significant impact on the severity of DSS-induced wasting in C57Bl/6 mice obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Jax mice) (Fig. S2). Surprisingly, we found that C57Bl/6 from the UC Berkeley colony (CB mice) showed significantly less wasting when DSS was coupled with AVNM treatment (Fig. 1C, S2).

Fig. 1. Effects of E. coli O21:H+ on DSS-induced skeletal muscle atrophy.

(A–B) Jax mice were treated with 5% DSS. (A) Percent original weight. (B) Leg muscle mass at 7-days. Representative experiment (N = 4–6) using 5 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. (C) Percent original weight of colony born C57Bl/6 mice (UC Berekely) treated with ampicillin, vancomycin, neomycin, metronidazole and 5% DSS (methods). Representative experiment (N = 3) using 4 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. (D) Percent original weight of 5% DSS-treated Jax mice gavaged with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle (methods). Representative experiment (N = 6) using 4 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. Fig. S3 shows untreated control mice +/− E. coli O21:H+. (E–F) Germ free Swiss Webster (SW) mice gavaged with 5×108 E. coli O21:H+ or E. coli MG1655 (methods) and treated with 5% DSS. (E) Percent original weight. (F) Leg muscle mass at 5-days from a subset of mice in (E) that were weight matched at Day 0. Representative experiment (N = 4) using 5–7 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. Fig. S3 shows monocolonized SW controls. (G) Percent survival of Jax mice administered E. coli O21:H+ or heat-killed E. coli O21:H+ (methods) and treated with 5% DSS for 7-days, after which DSS was no longer administered. Results are from two independent experiments using 4–7 mice per group per experiment. Log rank analysis. Survival analyses of untreated control +/− E. coli O21:H+ mice have been carried out for one year with no deaths from either group. Vehicle/DSS treated mice exhibit similar death kinetics as heat-killed/DSS treated mice. **** p < 0.0001, *** p < 0.0005, ** p < 0.005, * p < 0.05. EDL = extensor digitorum longus, TA = tibialis anterior. Experiments terminated for postmortem analyses at indicated day when one or more mice lost (A, B, D, E, F) >15% body weight in accordance with our Salk animal protocol or (C) >20% weight loss in accordance with our animal protocol (Berkeley).

We hypothesized that differences in the microbiota composition between Jax and CB mice may account for the differences we observed in wasting pathogenesis in response to AVNM plus DSS. We cultured from the ceca of CB mice an AVNM resistant (AVNMR) population of bacteria that was not present in Jax mice (Fig. S2). Upon co-housing with AVNM-treated CB mice, AVNM-treated Jax mice became colonized with AVNMR bacteria and were now protected from DSS-induced wasting, demonstrating that protection from wasting and CB associated AVNMR bacteria can be horizontally transferred to otherwise wasting-susceptible animals (Fig S2).

We performed culture-independent analysis of amplicons generated by primers specific to the V3 and V4 variable regions of bacterial 16S ribosomal RNA genes of cecal content samples from CB and Jax mice treated with AVNM for 5-days (11). The resulting bacterial communities detected were compared phylogentically (11). We found that AVNM-treated CB mice hosted large numbers of Escherichia spp. compared to AVNM-treated Jax mice (Fig. S2). Using culturing techniques, serotyping, genetic and molecular characterization (11), we isolated a single AVNMR Escherichia from the ceca of CB mice that we classified as an E. coli O21:H+ strain that was absent from Jax mice (Fig. S2 and (11)). We performed multilocus sequence typing (MLST) by analyzing seven loci of E. coli O21:H+ ((11) Table S1, Table S2) and found this E. coli to be a perfect match at these loci for E. colis of the strain ST101.

Oral administration of E. coli O21:H+ resulted in colonization of the intestine of Jax mice, but had no significant effect on weight, muscle mass, fat mass or food consumption under homeostatic conditions (Fig. S3). However, upon DSS treatment, E. coli O21:H+ Jax mice showed significantly less wasting than DSS-treated vehicle mice (Fig. 1D, S4). Jax mice administered heat-killed E. coli O21:H+ or live doses of the commensal strain E. coli MG1655 exhibited similar wasting as vehicle mice (Fig. S4). In accordance with our animal protocol we used >15% weight loss as a clinical endpoint. We terminated all experiments on the day post challenge in which one or more animals exhibited >15% weight loss and harvested tissues for postmortem analyses. This time point is consistent for a particular disease model but varies among models due to different disease kinetics. In all experiments, the number of animals and replication numbers were chosen as necessary to provide significance or lack there of and are reported in the figure legends (11).

We monocolonized germ free Swiss Webster (SW) mice by oral gavage with E. coli O21:H+ or E. coli MG1655, treated with DSS and monitored wasting. These strains colonized the intestines of SW mice equivalently (Fig. S4). Compared to E. coli MG1655-colonized Jax mice, SW E. coli MG1655-monocolonized mice were more susceptible to DSS with animals of the later beginning to exhibit >15% weight loss 5-days post treatment due to muscle and fat loss (Fig. 1E–F, S4). By contrast, E. coli O21:H+-monocolonized mice did not lose weight (Fig. 1E–F, S4). Thus, E. coli O21:H+ mediated protection does not require other microbiota constituents.

E. coli O21:H+ and E. coli MG1655 LPS were equivalent in their ability to stimulate the innate immune mediator Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) (Fig. S4). E. coli O21:H+-monocolonized mice were more susceptible to an i.p. challenge of E. coli O21:H+ compared to E. coli MG1655-monocolonized mice that received an i.p. challenge of E. coli MG1655 (Fig. S4). The canonical proinflammatory cytokines associated with wasting, TNFα, IL-1β and IL-6, were not downregulated in E. coli O21:H+ mice nor was there any difference in intestinal inflammation between DSS-treated vehicle and E. coli O21:H+ mice (Fig. S5). Thus differences in LPS levels, stimulatory capacity or responsiveness to E. coli O21:H+ were not responsible for the reduced wasting observed in E. coli O21:H+ mice upon DSS challenge. Likewise, we found no difference in intestinal tissue damage in wasting susceptible and wasting protected animals as indicated by no differences in epithelial cell loss, hyperplasia, edema or fibrosis (Fig. S5).

Metabolic changes observed during wasting are distinct from those observed under conditions of food deprivation, and nutritional interventions cannot reverse wasting (12–14). The DSS-induced anorexic response was equivalent in vehicle and E. coli O21:H+ animals (Fig. S4). The comprehensive lab animal monitoring system (CLAMS), revealed no differences in the rates of oxygen consumption or metabolic rate, carbon dioxide production, respiratory exchange ratio, activity or heat production of DSS-treated animals with and without E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. S6).

In untreated mice, E. coli O21:H+ had no effect on host survival (carried out to one year). Interestingly, upon DSS treatment, 70% of Jax mice given E. coli O21:H+, survived, whereas 100% of control Jax mice that were wasting susceptible died within twelve days of treatment initiation (Fig. 1G).

We previously identified an E. coli O21:H+ strain in a sepsis model caused by intestinal insult (15). Muscle wasting is a consequence of sepsis. Mice in this model and a model of sepsis induced by i.v. injection with this microbe, were protected from wasting (15). We therefore asked if E. coli O21:H+ ST101 identified in the current study prevents wasting induced by other microbes as follows.

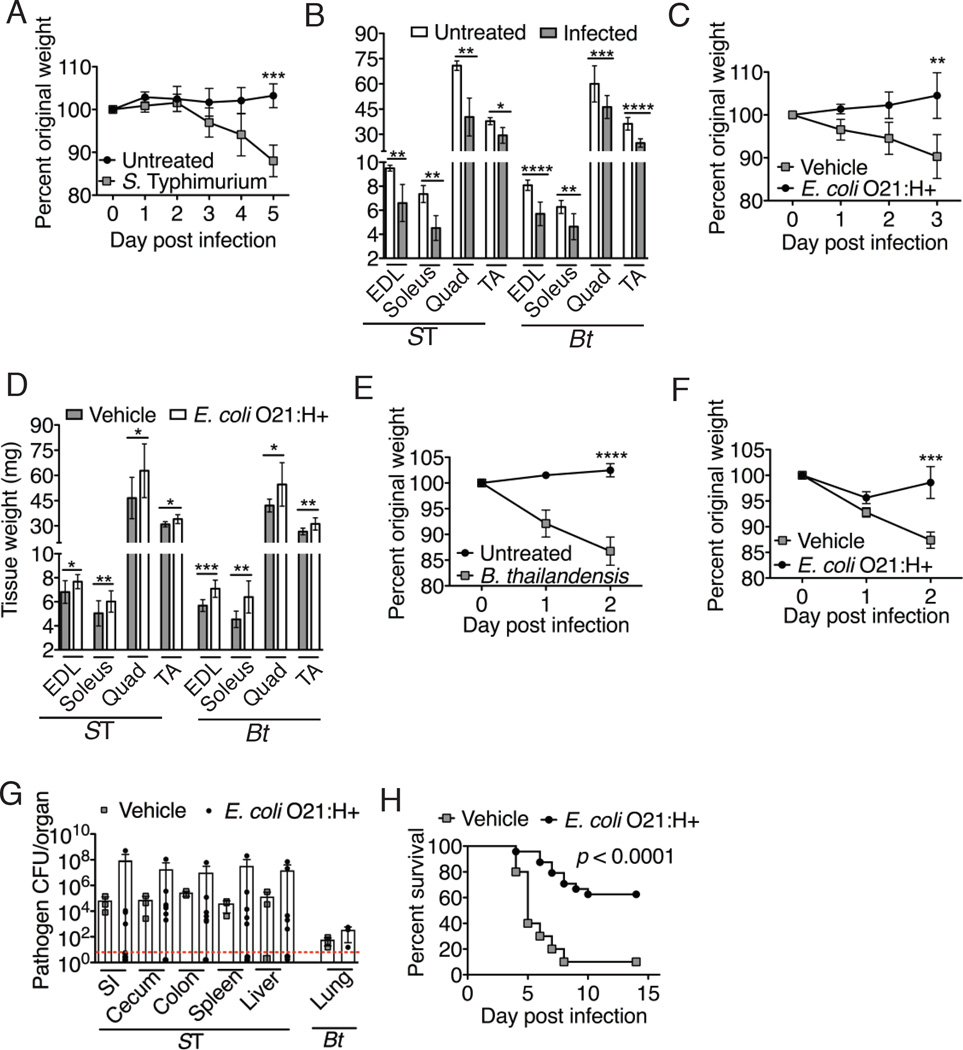

The oral pathogen Salmonella Typhimurium, induces wasting of muscle and adipose tissue in Jax mice (Fig. 2A–B, S7). E. coli O21:H+ Jax mice did not show weight loss, skeletal muscle or adipose tissue wasting when infected orally with S. Typhimurium compared to vehicle-treated infected Jax mice (Fig. 2C–D, Fig. S7).

Fig. 2. Effects of E. coli O21:H+ colonization on muscle wasting induced by infections.

(A) Percent original weight of Jax mice orally infected with 8.5×106 S. Typhimurium. Representative experiment (N = 3) using 5 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. (B) Leg muscle mass from S. Typhimurium-infected mice in (A) at Day 5(ST) or B. thailandensis-infected mice in (E) at Day 2 (Bt). Representative experiment (N = 3) using 5 animals per group, shown as mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. (C) Percent original weight of Jax mice gavaged with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and orally infected with 2×107 S. Typhimurium. Representative experiment (N = 7) using 4–5 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. Fig. S3 shows untreated control mice +/− E. coli O21:H+. (D) Leg muscle mass from infected E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle mice from (C) at Day 3 (ST) and from (F) at Day 2 (Bt). Representative experiment (N = 3–7) using 4–5 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. Fig. S3 shows control mice +/− E. coli O21:H+. (E–F) Jax mice were (E) left untreated or (F) gavaged with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle (methods) and intranasally infected with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis. Representative experiment (N = 3–7) using 4–5 animals per group, shown as mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. (G) S. Typhimurium (2×107 CFU inoculum) or B. thailandensis (2500 CFU inoculum) burdens in target tissues from infected mice +/− E. coli O21:H+ at 3-day (ST) or 2-day (Bt). B. thailandensis was not detected in the liver and spleen at this dose. Representative experiment (N = 3–7) using 3–7 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. Unpaired t-test. Dotted line indicates limit of detection. (H) Percent survival of Jax mice treated with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle orally infected with 2×107 S. Typhimurium. Results are from two independent experiments with 10–12 animals per group per experiment. Log rank analysis. ****p < 0.0001 *** p < 0.0005, ** p < 0.005, * p < 0.05. Postmortem analyses at day when one or more mice lost >15% body weight. EDL = extensor digitorum longus, TA = tibialis anterior.

We tested whether E. coli O21:H+ could antagonize wasting in the Burkholderia thailandensis pneumonia model in which there is no compromise of the gut barrier. Consistent with critically ill patients with pulmonary dysfunction (16), intranasally infected Jax mice exhibited rapid wasting (~15% weight loss by 2-day postinfection) characterized by a depletion of both muscle and fat (Fig. 2B, E, S7). Histological analysis showed that the intestinal barrier remained intact during infection in contrast to DSS-treated animals that exhibited leaky gut (Fig. S5, S7). To assess gut barrier function, B. thailandensis infected mice were gavaged with FITC-dextran, but serum FITC remained negative, in contrast to serum from DSS-treated mice, confirming the gut barrier was not breached (Fig. S7). B. thailandensis-infected/E. coli O21:H+-colonized Jax mice showed a ~2% decrease in body weight with significantly less muscle and fat wasting than infected mice given vehicle, which exhibited a ~15% decrease in weight (Fig. 2D, F, S7). Consistent with our findings with DSS, E. coli O21:H+ mitigation of S. Typhimurium-and B. thailandensis-induced wasting was independent of changes in the infection-induced anorexic response, caloric absorption by the intestine or alterations in oxygen consumption, carbon dioxide production, activity levels or heat production (Fig. S7, S8). E. coli O21:H+ colonization did not result in down-regulation of systemic TNFα, IL-1β or IL-6, nor with a reduction in tissue damage (S. Typhimurium-liver, spleen; B. thailandensis- lung, liver, spleen) (Fig. S9–S11). Consistent with previous reports (17), intestinal pathology in S. Typhimurium infected animals was minimal and indistinguishable in animals with and without E. coli O21:H+, remaining at background levels (Fig. S10). The pathogen burdens in E. coli O21:H+ animals were not reduced compared to infected animals treated with vehicle (Fig. 2G, B. thailandensis did not disseminate to the spleen and liver at our doses). Thus, the presence of E. coli O21:H+ in the intestinal microbiota appears to reduce/inhibit lean body wasting induced by pathogens or intestinal injury. It is this protective effect, rather than pathogen killing, that significantly promoted survival of S. Typhiumurium-infected animals given E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. 2H, S7).

Transcriptional induction of the E3 ubiquitin ligases Atrogin-1 and Murf1 is crucial for muscle atrophy (18–20) and are induced upon challenge with B. thailandensis, S. Typhimurium or DSS (Fig. 3A, S12). Induction of Atrogin-1 and Murf1 did not occur in the muscle of E. coli O21:H+ Jax mice challenged with pathogen or DSS and were at equivalent levels found in untreated mice with and without E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. 3A, S12).

Fig. 3. Gut colonisation by E. coli O21:H+ associated with down-regulation of muscle atrophy programs and maintenance of IGF-1 signaling during infection.

(A–B) Jax mice gavaged with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and intranasally infected with 1000 CFU B. thailandensis. (A) Murf1 and Atrogin-1 expression in leg muscle at 2-day postinfection normalized to ribosomal protein S17 (RPS17) expression. Representative experiment (N =3) using 4–9 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. (B) Serum IGF-1 at 2-days. Representative experiment (N = 3) using 7–9 animals per group, shown as mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. See Fig. S14 for additional controls. (C–D) Jax mice were given 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and intranasally infected with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis. (C) IGF-1 levels in WAT and (D) E. coli O21:H+ levels in the WAT at Day 2. Representative experiment (N = 4) using 6–10 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. Red line = limit of detection. (E–H) Mice given 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle were injected i.p. with anti-IGF-1 or IgG isotype control antibody and intranasally infected with 1000 CFU B. thailandensis. (E) Percent original weight. Results are from two independent experiments using 6–9 mice per group per experiment (12–17 mice total), mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. Fig. S14 for additional controls. (F) Leg muscle mass and (G) Adipose tissue mass at 2-days. EDL = extensor digitorum longus, TA = tibialis anterior. GWAT = gonadal white adipose tissue, RPWAT = retroperitoneal WAT, IWAT = inguinal WAT, BAT = brown adipose tissue. Results are from the two independent experiments described in (E) using 5–9 mice weight matched at day 0 (~18g) for each group for each experiment (10–14 mice total), mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. (H) Murf1 and Atrogin-1 expression in leg muscle at 2-day and normalized to RPS17. Representative experiment (N = 2) using 5–9 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. ****p < 0.0001, ***p = 0.0006, **p < 0.005, *p < 0.05. Postmortem analyses at day when one or more mice lost >15% body weight.

RNAseq analysis of leg muscles from S. Typhimurium-infected mice revealed that components of the insulin/insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) signaling pathway, muscle physiology and metabolism, were upregulated in E. coli O21:H+ mice compared to infected vehicle mice (Fig. S13). The IGF-1/PI3K/AKT pathway is a master regulator of muscle size that activates factors for protein synthesis and regeneration as well as the down-regulation of Atrogin-1 and Murf1 expression in atrophying muscle (21–23). Untreated Jax mice with or without E. coli O21:H+ had comparable levels of serum IGF-1 as measured by ELISA ((11) and Fig. S13) and showed no muscle hypertrophy (Fig. S3); likewise when infected with S. Typhimurium, B. thailandensis or given DSS, serum levels of IGF-1 and downstream signaling components in muscle (IGFR and AKT) in E. coli O21:H+ mice were sustained activation levels comparable to untreated animals, while activation levels in challenged animals given vehicle decreased significantly (Fig. 3B, S13, S14).

IGF-1 is produced primarily by the liver in response to growth hormone (GH) (24). We found that serum levels of GH, liver Igf-1 expression and IGF-1 protein levels in the liver, muscle and intestine were unchanged in challenged E. coli O21:H+ animals compared to challenged animals treated with vehicle or unchallenged animals with and without E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. S13). Instead, during challenge with pathogens or DSS, white adipose tissue (WAT) from challenged E. coli O21:H+ mice showed higher levels of IGF-1 compared to WAT from challenged vehicle animals and unchallenged animals with and without E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. 3C, S15). This was associated with E. coli O21:H+ colonization of the WAT, but not the muscle or WAT associated lymph nodes (Fig. 3D, S15). B. thailandensis and S. Typhimurium did not infect the WAT. Thus sustained systemic levels of IGF-1 by E. coli O21:H+ is associated with increased WAT IGF-1 levels and colonization of the WAT by this commensal. A role for WAT-derived IGF eliciting systemic effects is supported by previous studies (25).

Systemic administration of an IGF-1 neutralizing antibody to E. coli O21:H+ mice in the absence of pathogen infection had no effect on mouse weight (Fig. S15). When given the neutralizing antibody i.p., E. coli O21:H+ mice infected with B. thailandensis were no longer protected from wasting (Fig, 3E–F, S15). These animals showed significant weight loss, muscle depletion (but not fat loss), a decrease in muscle IGF-1 signaling and an increase in muscle expression of Atrogin-1 and Murf1 compared to infected E. coli O21:H+ Jax mice given an IgG isotype control antibody (Fig. 3E–H, S15–16). There was no significant differences in the ceca levels of E. coli O21:H+ or B. thailandensis lung infection levels in E. coli O21:H+ mice that were treated with anti-IGF-1 antibody or the IgG isotype control (Fig S15).

The inflammasome – a cytoplasmic multi-protein complex required for activation of the Caspase-1 (CASP1) protease (26), has recently emerged as a critical regulator of host-microbiota interactions and metabolism (26, 27). We therefore examined Casp1−/− mice, which are also deficient for CASP11 (28). In contrast to wild type mice, oral administration of E. coli O21:H+ to B. thailandensis-infected Casp1−/−11−/− mice did not protect against muscle wasting nor prevented the upregulation of Murf1 and Atrogin-1 in muscle nor prevented an infection-induced drop in systemic IGF-1 (Fig. 4A–C, S17). Similarly, IGF-1 levels in the WAT were less in B. thailandensis-infected Casp1−/−11−/− E. coli O21:H+ mice than in infected wild type E. coli O21:H+ mice (Fig. S17). Lung infection levels of B. thailandensis and intestinal levels of E. coli O21:H+ were not significantly different between infected Casp1−/−11−/− and wild type mice with or without E. coli O21:H+ (Fig S17).

Fig. 4. The Nlrc4 inflammasome is required for sustaining IGF-1 levels and mediates the E. coli O21:H+ associated protection against muscle wasting promoted by pathogenic infection.

(A–C) Wild-type and Casp1−/−11−/− mice were administered 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and then intranasally infected with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis as described in methods. (A) Percent original weight at day 2. See Fig. S3 for additional controls. (B) Expression of Murf1 and Atrogin-1 were determined in leg muscle at 2-day postinfection normalized to expression levels of RPS17. (C) Serum IGF-1 quantified at day 2. Representative experiment (N = 3) using 10 animals per wildtype group and 5–7 mice per Casp1−/−11−/− group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. (D) Wild-type and Nlrc4−/− mice were given 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and infected intranasally with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis. Serum levels of IGF-1 at 2-days postinfection were measured. Representative experiment (N = 2) using 10 animals per wildtype group and 5 mice per Nlrc4−/− group, shown as mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. (E) Jax mice were given with 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and then intranasally infected with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis as described in Methods and serum IL-18 levels were measured at 2-days postinfection. Representative experiment (N = 2) using 10 animals per group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. (F) Wild-type and Il1β−/−Il18−/− mice were administered 5×108 CFU E. coli O21:H+ or vehicle and then intranasally infected with 2500 CFU B. thailandensis. Serum levels of IGF-1 at 2-days postinfection were measured. Representative experiment (N = 3) using 10 animals per wildtype group and 8 mice per Il1β−/−Il18−/− group, mean +/− S.D. ANOVA. ***p < 0.0003, **p < 0.006, *p < 0.05. Experiment was terminated at 2-days for postmortem analyses when one or more mice lost >15% body weight in accordance with our Salk animal protocol. (C, D, F) see Fig. S14 for additional controls.

Several distinct inflammasomes have been described, each of which contains a protein of the nucleotide-binding domain-containing (NLR) protein superfamily. The NLRC4 inflammasome is activated by the inner rod protein of type three secretion systems (TTSS) and by flagellin of Gram-negative bacteria (26), both of which are encoded by E. coli O21:H+ (Table S2). Similarly to Casp1−/−11−/− mice, the presence of E. coli O21:H+ in B. thailandensis-infected Nlrc4−/− mice did not antagonize wasting nor prevented an infection-induced drop in systemic IGF-1 levels (Fig. 4D, S18).

Colonization levels of E. coli O21:H+ in the WAT deposits of B. thailandensis-infected Casp1−/−11−/− were equivalent to those in the WAT of infected-wild type mice (Fig. S17). Therefore the inflammasome is not necessary for translocation of E. coli O21:H+ from the intestine to the WAT.

Activation of any inflammasome leads to maturation of the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and IL-18. Systemic levels of IL-18 in B. thailandensis-infected E. coli O21:H+ wild type mice were increased compared to infected vehicle mice, with no differences in IL-1β levels (Fig. 4E, S5). The protective effect of E. coli O21:H+ functioned in Il1β−/− mice but not in Il1β−/−Il18−/− mice in which E. coli O21:H+ did not protect from B. thailandensis-induced muscle and fat wasting (Fig. S18). B. thailandensis-infection levels in the lung and E. coli O21:H+ levels in the intestine and WAT were similar between infected wild type and Il1β−/−Il18−/− mice given E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. S18). When Il1β−/−Il18−/− mice were challenged with B. thailandensis IGF-1 loss was not prevented by E. coli O21:H+ (Fig. 4F). We conclude that the ability of E. coli O21:H+ to maintain levels of IGF-1 during challenge is mediated by the Nlrc4 inflammasome via IL-18, (with a possible synergistic role for IL-1β) and thereby prevents muscle wasting and promotes disease tolerance.

The intestinal microbiota performs essential functions for its host to achieve metabolic homeostasis. Our results strongly suggest that a specific constituent of the murine intestinal microbiota, E. coli O21:H+, antagonizes wasting triggered by infections and intestinal injury. During homeostasis, E. coli O21:H+ remains in the intestine, has no effect on weight, body composition or IGF-1 levels. During challenge, E. coli O21:H+ sustains systemic IGF-1 and signaling of IGF-1 in muscle to prevent wasting and promote disease tolerance (29–31) independent of metabolic changes, food consumption, caloric uptake, inflammation or tissue damage. This protection is associated with challenge-induced translocation of E. coli O21:H+ to WAT and activation of the NLRC4 inflammasome that correlates with increased production of IGF-1 by WAT. The ability to translocate to and colonize the WAT distinguishes E. coli O21:H+ from other microbes (including B. thailandensis and S. Typhimurium) that can activate inflammasomes where its presence antagonizes wasting in an inflammasome-dependent manner possibly induced by its flagellin or the inner rod protein of the its TTSS, eprJ. (Fig. S19).

The microbiota is crucial for the development and maintenance of a robust immune system and resistance defenses (32, 33). Discovery of a molecular mechanism by which the microbiota can promote tolerance to infection provides a perspective into the evolutionary forces that have driven the co-evolution of host-microbiota interactions.

Supplementary Material

Protective Effects of an E. coli strain.

Infection and intestinal damage can trigger cachexia, culminating in severe muscle wasting and loss of fat. How this happens is poorly understood. Palaferri-Schieber et al. have discovered a protective Escherichia coli strain in their mouse colony. If mice were intestinally colonized with the E. coli and infected with Salmonella or with Burkholderia, which only infects lungs, they did not waste away. Without the E. coli the mice became fatally sick. The protective effect of the E. coli was mediated via an innate immune mechanism that ensured muscle-signalling pathways were not damaged by infection. Thus, the E. coli allowed its host to tolerate and survive the pathogens.

Acknowledgments

We thank R. Vance for mice and reagents. G. Barton and M. Koch for TLR4-ELAM NFkB reagents. M. Montminy and E. Wiater for use of the EchoMRI and MiSeq sequencer and technical assistance. S. Mazmanian, S. McBride, J. Sonnenburg and S. Higginbottom for germ free mice and advice. D. Monack and F. Re for Salmonella and Burkholderia strains. W. Fan and S. Bapat for reagents and help with muscle and fat anatomy and physiology. I. Verma for use of the BioRad Bio-Plex MAGPIX multiplex reader, D. Cook for technical assistance with Luminex assays. M. Ku and S. Heinz for advice and technical assistance with RNAseq and metagenomics analyses. R. Shaw and P. Hollstein for western blot reagents and advice, G. Van Gerpen, K. Kujawa and M. Bouchard for administrative assistance with establishing our gnotobiotic facility. D. Schneider and D. Green for helpful discussions and thoughtful comments on the manuscript. A special thanks to Robert Lamberton for continuous support. This work was supported by NIH grant R01AI114929 (J.S.A), the NOMIS Foundation, the Searle Scholar Foundation (J.S.A), the Ray Thomas Edward Foundation (J.S.A.). NIH grants DK0577978 (R.M.E.) and CA014195, the Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust (#2012-PG-MED002), the Samuel Waxman Cancer Research Foundation, and Ipsen/Biomeasure. R.M.E. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute at the Salk Institute and March of Dimes Chair in Molecular and Developmental Biology.

Footnotes

Data described in this paper can be found in the supplementary materials.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Delano MJ, Moldawer LL. The origins of cachexia in acute and chronic inflammatory diseases. Nutrition in clinical practice : official publication of the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition. 2006;21:68–81. doi: 10.1177/011542650602100168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon K, et al. Definition and classification of cancer cachexia: an international consensus. The Lancet. Oncology. 2011;12:489–495. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70218-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villamor E, et al. Wasting and body composition of adults with pulmonary tuberculosis in relation to HIV-1 coinfection, socioeconomic status, and severity of tuberculosis. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2006;60:163–171. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasselgren PO. Catabolic response to stress and injury: implications for regulation. World journal of surgery. 2000;24:1452–1459. doi: 10.1007/s002680010262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Why cachexia kills: examining the causality of poor outcomes in wasting conditions. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2013;4:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s13539-013-0111-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicholson JK, et al. Host-gut microbiota metabolic interactions. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fisher RL. Wasting in chronic gastrointestinal diseases. The Journal of nutrition. 1999;129:252S–255S. doi: 10.1093/jn/129.1.252S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ubeda C, et al. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus domination of intestinal microbiota is enabled by antibiotic treatment in mice and precedes bloodstream invasion in humans. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:4332–4341. doi: 10.1172/JCI43918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okayasu I, et al. A novel method in the induction of reliable experimental acute and chronic ulcerative colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:694–702. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90290-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Supplementary Materials.

- 12.Fearon KC, Glass DJ, Guttridge DC. Cancer cachexia: mediators, signaling, and metabolic pathways. Cell metabolism. 2012;16:153–166. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tisdale MJ. Mechanisms of cancer cachexia. Physiological reviews. 2009;89:381–410. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00016.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ovesen L, Allingstrup L, Hannibal J, Mortensen EL, Hansen OP. Effect of dietary counseling on food intake, body weight, response rate, survival, and quality of life in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy: a prospective, randomized study. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:2043–2049. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.10.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayres JS, Trinidad NJ, Vance RE. Lethal inflammasome activation by a multidrug-resistant pathobiont upon antibiotic disruption of the microbiota. Nat Med. 2012;18:799–806. doi: 10.1038/nm.2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Puthucheary ZA, et al. Acute skeletal muscle wasting in critical illness. Jama. 2013;310:1591–1600. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.278481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barthel M, et al. Pretreatment of mice with streptomycin provides a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium colitis model that allows analysis of both pathogen and host. Infection and immunity. 2003;71:2839–2858. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.5.2839-2858.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen S, et al. During muscle atrophy, thick, but not thin, filament components are degraded by MuRF1-dependent ubiquitylation. The Journal of cell biology. 2009;185:1083–1095. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bodine SC, et al. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science. 2001;294:1704–1708. doi: 10.1126/science.1065874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomes MD, Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Navon A, Goldberg AL. Atrogin-1, a muscle-specific F-box protein highly expressed during muscle atrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:14440–14445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251541198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sacheck JM, Ohtsuka A, McLary SC, Goldberg AL. IGF-I stimulates muscle growth by suppressing protein breakdown and expression of atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1. American journal of physiology. Endocrinology and metabolism. 2004;287:E591–E601. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00073.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stitt TN, et al. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Molecular cell. 2004;14:395–403. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00211-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemmons DR. Role of IGF-I in skeletal muscle mass maintenance. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2009;20:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chia DJ. Minireview: mechanisms of growth hormone-mediated gene regulation. Mol Endocrinol. 2014;28:1012–1025. doi: 10.1210/me.2014-1099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kloting N, et al. Autocrine IGF-1 action in adipocytes controls systemic IGF-1 concentrations and growth. Diabetes. 2008;57:2074–2082. doi: 10.2337/db07-1538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Moltke J, Ayres JS, Kofoed EM, Chavarria-Smith J, Vance RE. Recognition of bacteria by inflammasomes. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:73–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henao-Mejia J, Elinav E, Thaiss CA, Flavell RA. Inflammasomes and metabolic disease. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014;76:57–78. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021113-170324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kayagaki N, et al. Non-canonical inflammasome activation targets caspase-11. Nature. 2011;479:117–121. doi: 10.1038/nature10558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ayres JS, Schneider DS. Tolerance of infections. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;30:271–294. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schneider DS, Ayres JS. Two ways to survive infection: what resistance and tolerance can teach us about treating infectious diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:889–895. doi: 10.1038/nri2432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medzhitov R, Schneider DS, Soares MP. Disease tolerance as a defense strategy. Science. 2012;335:936–941. doi: 10.1126/science.1214935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ivanov II, et al. Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell. 2009;139:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.09.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ichinohe T, et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Song YH, et al. Muscle-specific expression of IGF-1 blocks angiotensin II-induced skeletal muscle wasting. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2005;115:451–458. doi: 10.1172/JCI22324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dobin A, et al. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Skuta C, Bartunek P, Svozil D. InCHlib - interactive cluster heatmap for web applications. Journal of cheminformatics. 2014;6:44. doi: 10.1186/s13321-014-0044-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ren Y, et al. Characterization of Escherichia coli O3 and O21 O antigen gene clusters and development of serogroup-specific PCR assays. Journal of microbiological methods. 2008;75:329–334. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Machado J, Grimont F, Grimont PA. Identification of Escherichia coli flagellar types by restriction of the amplified fliC gene. Research in microbiology. 2000;151:535–546. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(00)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cooper HS, Murthy SN, Shah RS, Sedergran DJ. Clinicopathologic study of dextran sulfate sodium experimental murine colitis. Laboratory investigation; a journal of technical methods and pathology. 1993;69:238–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Jong HK, et al. Limited role for ASC and NLRP3 during in vivo Salmonella Typhimurium infection. BMC immunology. 2014;15:30. doi: 10.1186/s12865-014-0030-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gonzalez-Escobedo G, La Perle KM, Gunn JS. Histopathological analysis of Salmonella chronic carriage in the mouse hepatopancreatobiliary system. PloS one. 2013;8:e84058. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wiersinga WJ, et al. Inflammation patterns induced by different Burkholderia species in mice. Cellular microbiology. 2008;10:81–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.