Summary

Whole exome sequencing and copy number aberration (CNA) analysis was performed on cells taken from peripheral blood (PB) and lymph nodes (LN) of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL). Of 64 non-silent somatic mutations, 54 (84.4%) were clonal in both compartments, 3 (4.7%) were PB-specific and 7 (10.9%) were LN-specific. Most of the LN- or PB-specific mutations were subclonal in the other corresponding compartment (variant frequency 0.5-5.3%). Of 41 CNAs, 27 (65.8%) were shared by both compartments and 7 (17.1%) were LN- or PB-specific. Overall, 6 of 9 cases (66.7%) showed genomic differences between the compartments. At subsequent relapse, Case 10, with 6 LN-specific lesions, and Case 100, with 6 LN-specific and 8 PB-specific lesions, showed, in the PB, the clonal expansion of LN-derived lesions with an adverse impact: SF3B1 mutation, BIRC3 deletion, del8(p23.3-p11.1), del9(p24.3-p13.1) and gain 2(p25.3-p14). CLL shows an intra-patient clonal heterogeneity according to the disease compartment, with both LN and PB-specific mutations/CNAs. The LN microenvironment might contribute to the clonal selection of unfavourable lesions, as LN-derived mutations/CNAs can appear in the PB at relapse.

Keywords: Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, lymph node, whole exome sequencing, copy number aberrations, relapse

Introduction

Cancers are composed of cells with distinct molecular and phenotypic features, a phenomenon termed intratumour heterogeneity. Next generation sequencing (NGS) has formally documented the genetic heterogeneity within primary tumours and between a primary tumour and its metastatic sites. This heterogeneity can contribute to Darwinian selection of preexisting drug-resistant clones and predict clonal evolution and treatment failure. The different genetic pattern among distinct tumour sites also implies that the evaluation of a single disease compartment may underestimate the mutational complexity of tumours in toto (Jamal-Hanjani et al, 2015).

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is characterized by the accumulation of neoplastic B cells in the peripheral blood (PB), bone marrow (BM) and lymph nodes (LN) (Chiorazzi et al, 2005). The crosstalk of CLL cells with accessory cells and soluble factors in microenvironmental niches within specialized tissue is nowadays considered pivotal for favouring disease maintenance and progression (Caligaris-Cappio & Ghia, 2008; Burger & Gribben, 2014). Consistently, CLL cells derived from LN show an overexpression of genes related to cell proliferation, activation of the B-cell receptor (BCR) and nuclear factor-kappa B pathways, which is absent in PB- and BM-derived cells (Herishanu et al, 2011). In addition, the proliferating component in CLL is restricted to the LN, while the vast majority of PB CLL cells are non-proliferating (Messmer et al, 2005; Calissano et al, 2009; Calissano et al, 2011), supporting the notion that proliferation centres are the key site for the expansion and maintenance of the B-cell clone.

Clonal evolution and outgrowth of cellular variants with additional genetic abnormalities are the major causes of disease progression in CLL (Landau et al, 2013). Because in tumours DNA lesions occur during the S phase of the cell cycle, CLL proliferating cells in the LN compartment might be at the origin of clonal evolution. However, a formal proof that clonal evolution may originate in the LN compartment is lacking.

NGS has allowed major contributions in the identification of previously unknown gene mutations with clinical significance in haematological malignancies, particularly CLL (Foà et al, 2013). In the present study, we applied NGS and copy number aberration (CNA) analysis to CLL cells synchronously extracted from PB and LN to investigate the unexplored genomic architecture of the disease according to the compartment at the clonal and subclonal levels.

Methods

Study population

Nine patients with CLL from two Italian centres were included in the study of whole exome sequencing (WES) and CNAs of CLL cells synchronously derived from PB and LN (Supplementary Fig. 1). Paired germline DNA was also analysed.

The biopsy of adenopathies was required for clinical indications, i.e. bulky or rapidly enlarging LN. Inclusion criteria included: i) absence of Richter syndrome; ii) PB and LN samples with >75% clonal CD19+/CD5+ cells, as assessed by flow cytometry on whole blood and LN cell suspensions; iii) availability, quality and proper amount of both tumour and germline DNA.

All patients gave their informed consent to blood and LN collection and to the biological analyses included in the present study according to the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the Ethical Committees of Policlinico Umberto I, “Sapienza” University of Rome (rif. 2182/16.06.2011).

All samples satisfied the diagnostic criteria for CLL (Hallek et al, 2008). IGHV gene analysis, CD38 and ZAP70 expression, and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses were performed as previously described (Del Giudice et al, 2011).

Mutation analysis of TP53 exons 4 to 9 was carried out by DNA direct sequencing (ABI PRISM 3100 Genetic Analyzer, Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), as reported (Del Giudice et al, 2011).

Matched germline DNA, extracted from saliva, proved to be negative for patients-specific IGHV-D-J rearrangements in every case. Bacterial DNA contamination was excluded by performing the Quantifiler assay (Applied Biosystems).

Direct Sanger sequencing of NOTCH1 was also performed in all PB samples as described (Fabbri et al, 2011).

All patients but 1 were untreated and at first disease progression at the time of the study; Case 100 was in first relapse after treatment. All of the patients underwent treatment with conventional chemoimmunotherapy. The clinical and biological features of the patients are summarized in Supplementary Table I: 6 cases showed unmutated (UNM) and 3 mutated (MUT) IGHV; at FISH analysis, 1 case showed del(17p) in combination with del(11q), 2 had del(11q), 3 had +12, 2 had isolated del(13q) and 1 had no abnormalities. No case showed TP53 or NOTCH1 mutations in the PB or LN compartment (Supplementary Table I).

Whole exome sequencing, sequence mapping and identification of tumour-specific variants

Libraries of tumour/normal DNA were constructed and sequenced by Illumina HiSeq 2000 analyzer (Illumina, San Diego, CA). The performance of the sequencing is summarized in Supplementary Table II. The SAVI (statistical algorithm for variant frequency identification) pipeline was applied to identify somatic mutations (Trifonov et al, 2013). The pipeline takes as input the reads produced by Ilumina HiSeq 2000 analyzer, filters low-quality reads and maps the rest onto human genome hg19. After the mapping, small insertions/deletions (INDELs) and single nucleotide variations are obtained for each genomic location and a Bayesian prior model for the distribution of allele frequencies for each sample is constructed. To genotype the sample, we use the Bayesian prior model to obtain posterior confidence intervals for the frequency of each mutation. To identify somatic mutations, each tumour sample is compared with corresponding normal sample from the same patient. Based on the Bayesian posterior model, the confidence interval of the difference of mutation frequency is estimated. A mutation is predicted to be somatic if the lower bound of this confidence interval is greater than zero.

Validation of candidate somatic mutations by Sanger sequencing

Candidate non-silent somatic mutations were subjected to validation by conventional Sanger-based re-sequencing of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products obtained from PB and LN tumours and paired germline high molecular weight genomic DNA using primers specific for the exon encompassing the variant. Primers (available upon request) were derived from previously published studies (Parsons et al, 2011) or were custom-designed using the Primer 3 online software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/primer3/) and the in silico PCR tool of the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) Human Genome database (http://genome.ucsc.edu/) to verify the uniqueness of the match.

Ultra-deep NGS

Amplicons known to harbour mutations were re-amplified from genomic DNA by oligonucleotides containing the gene-specific sequences, along with 10-bp multiplex identifiers (MID) tag for multiplexing and amplicon library A and B sequencing adapters, using a high fidelity Taq polimerase (FastStart High fidelity PCR System, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). PCR products were then individually purified using Agencourt AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA) and quantified using the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA kit (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA). Corresponding patient-specific amplicon pools were generated by combining each of the amplicons in an equimolar ratio for each patient sample. The pools were diluted to a concentration of 1×106 molecules per μl and processed using the GS Junior Series Lib-A method (Roche Diagnostics). Forward (A beads) and reverse (B beads) reactions were carried out using 5,000,000 beads per emulsion oil tube. The copy per bead ratio used was 1.1:1. The amplification reaction, breaking of the emulsions and enrichment of beads carrying amplified DNA were performed using the workflow as recommended by the manufacturer. Finally, the obtained amplicon library was loaded on a PicoTiterPlate (PTP) and subjected to ultra-deep-NGS on the Genome Sequencer Junior instrument (454 Life Science, Roche Diagnostics).

All reads from the ultra-deep sequencing were mapped to hg19 by the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA) software (Li & Durbin (2009). For a particular sample, a mutation was considered as present if at least one read supported the mutation. Variant allele frequency (VF) was then estimated by dividing total number of mapped reads in a given position. Mutations were considered clonal when identified by Sanger sequencing and represented by ≥10% VF by NGS. The same criteria were used to define the specificity of the distribution of clonal mutations in each compartment.

Copy number analysis by high-density Cytoscan array

Genomic DNA was extracted from paired PB-LN samples of 9 CLL patients using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) and the Nucleo spin tissue kit (Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany) from paired saliva samples. Genome-wide DNA profiles were obtained from high molecular weight genomic DNA (250 ng) using the Affymetrix Cytoscan high-density (HD) arrays and standard protocols (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The array contains more than 2.6×106 copy number markers, including 750.000 single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) probes. All the arrays were first checked for quality according to the following parameters: Mean Absolute Percentage Deviation (MAPD), SNP quality control (SNPQC) and waviness-standard deviation (waviness-sd), according to the manifacturer's instructions. Given the recent introduction of this array, the identification of regions of abnormal copy number was performed by multiple approaches: i) Chromosome Analysis Suite (ChAS, Affymetrix) software; ii) Partek Genomics Suite software (Partek Inc., St. Louis, MO); iii) the circular binary segmentation as detailed in previously published papers (Pasqualucci et al, 2011) and adapted to the Cytoscan HD array. Data analysis revealed a high degree of overlap between the different methods. However, for rigorousness purposes, only the CNAs identified by all these methods were retained. All the CNAs were visually inspected by dChipSNP software (https://sites.google.com/site/dchipsoft/). For normalization purposes, matched normal DNA was simultaneously analysed in order to exclude non tumour-related aberrations.

Results

Frequency and distribution of genetic lesions in the PB and LN compartment

Sanger, NGS and CNA analysis allowed us to define the clonal distribution of genetic lesions in the PB and LN compartments.

The bioinformatic analysis of WES data predicted a total of 68 non-silent somatic mutations; Sanger sequencing validated 64 of these mutations (94.1% validation rate) in 59 genes (Table I; Supplementary Table III). We defined the specificity of mutations’ distribution in each compartment according to their clonal representation by Sanger sequencing and NGS VF (see below). Thus, 84.4% (n=54/64) mutations were present in both compartments, 10.9% (n=7/64) were LN-specific = in 2 patients [Cases 10, 100] and 4.7% (n=3/64) were PB-specific in 3 patients Cases 11, 100, 103] (Table I; Fig. 1A; Supplementary material; Supplementary Table III).

Table I. Validated mutations per case and per compartment.

Variant allele frequency (VF) of the mutations is shown. Common mutations are unshaded, clonal lymph node (LN)-specific mutations are shaded dark grey and clonal peripheral blood (PB)-specific mutations a shaded light grey. VF of Case 11 is not available due to lack of material.

| Case | Gene | PB VF % | LN VF % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | PHKA2 L795H | 21.22 | 14.05 |

| PHKA2 V803F | 23.28 | 12.94 | |

| ADAMTS16 | 33.65 | 31.80 | |

| CEP250 | 21.81 | 21.22 | |

| ZNF536 | 40.39 | 39.93 | |

| COL22A1 | 52.05 | 55.39 | |

| SLC22A10 | 74.66 | 82.02 | |

| SPEN | 35.81 | 39.91 | |

| EGR2 | 33.31 | 44.17 | |

| RBMX | 25.21 | 44.44 | |

| TRPA1 | 15.52 | 32.7 | |

| DAPK1 | 0.7* | 19.61 | |

| ZNF215 | 3.6* | 35.79 | |

| 11 | CEP170 | na | na |

| GUCY1A3 | na | na | |

| LRRC66 | na | na | |

| LRRIQ1 | na | na | |

| PKD2 | na | na | |

| RAB11FIP5 | na | na | |

| RGS18 N163D | na | na | |

| RGS18 T157K | na | na | |

| LGSN | na | na | |

| 12 | CGREF1 | 37.47 | 45.31 |

| 100 | ATM | 19.37 | 11.38 |

| PDE7B | 43.68 | 45.88 | |

| BACE2 | 45.2 | 49.12 | |

| MUC5B R4967* | 16.04 | 9.60 | |

| C12orf71 | 0* | 33.24 | |

| KIF26B | 1.2* | 30.45 | |

| POLR2A | 1.3* | 29.97 | |

| SF3B1 | 5.93* | 33.90 | |

| WLS | 0.5* | 28.23 | |

| ABCC9 | 17.67 | 1.3* | |

| 101 | CEP112 | 38.05 | 37.88 |

| 0001R17 | 28.49 | 29.43 | |

| EPHA4 | 36.23 | 38.36 | |

| FBXW7 | 34.78 | 37.66 | |

| MYOC | 25.35 | 28.32 | |

| PPBP | 35.29 | 43.68 | |

| ADGRL2 | 34.07 | 43.21 | |

| BRINP3 | 24.01 | 35.38 | |

| 102 | SACS | 35.96 | 28.87 |

| ARFGAP3 | 30.61 | 30.35 | |

| POLR3B | 30.63 | 33.17 | |

| SF3B1 | 25.08 | 29.27 | |

| MGEA5 | 9.5 | 9.7 | |

| 103 | TNKS | 36.42 | 40.47 |

| IL13RA1 | 41.32 | 47.35 | |

| PLEK2 | 33.57 | 39.17 | |

| GEN1 | 38.31 | 45.75 | |

| TRIM7 | 34.16 | 45.52 | |

| SPEF2 | 32.51 | 43.84 | |

| MUC5B H3458Q | 40.77 | 0* | |

| 104 | HRNR | 16.27 | 10 |

| CPED1 | 30.1 | 29.49 | |

| HN1 | 29.68 | 42.58 | |

| SYNJ1 | 21.89 | 47.34 | |

| ZFHX4 | 19.22 | 47.26 | |

| 106 | NBPF6 | 21.74 | 12.82 |

| FREM2 | 32.32 | 39.39 | |

| ZNF667 | 29.55 | 37.99 | |

| FCHSD2 | 28.2 | 36.26 | |

| HIST1H4E | 35.04 | 45.93 | |

| SF3B1 | 28.05 | 41.46 |

ultra-deep sequencing

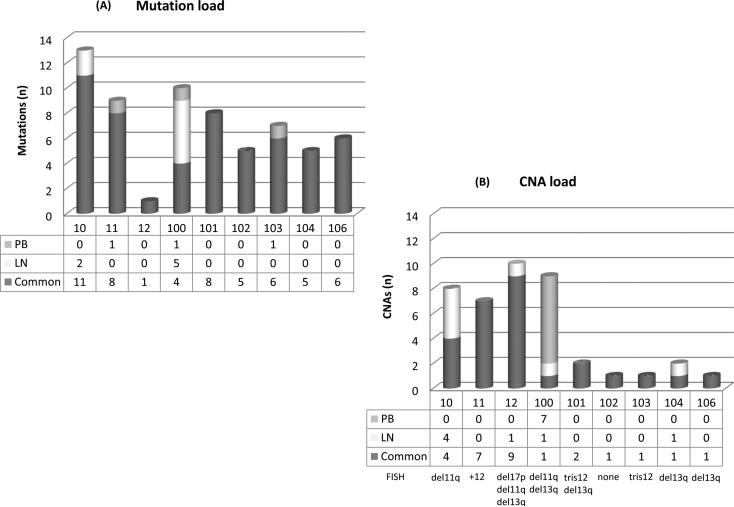

Figure 1. Frequency and distribution of genetic lesions in the PB and LN compartment.

(A) Load and distribution of mutations. The 64 validated non-silent somatic mutations are included. (B) Load and distribution of CNAs. The 41 identified CNAs are included. FISH lesions of each case are reported. Numbers under the bars refer to case numbers.

CNA, copy number aberration; PB, peripheral blood; LN, lymph node; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization

CNA analysis identified a total of 68 lesions, 34 in the PB and 34 in the LN samples (Table II; Supplementary material; Supplementary Table IV). A total of 27 CNAs (65.8%) were shared by paired LN and PB samples, while 7 CNAs (17.1%) were specific for the LN compartment in 4 patients [Cases 10, 12, 100, 104] and 7 lesions (17.1%) were PB-specific in 1 patient [Case 100] (Table II, Fig. 1B). Genes that were mutated by WES were not affected by CNAs, apart from ATM.

Table II. CNAs per case and per compartment.

PB lesions detected by FISH are also reported.

| Case | FISH PB | Common CNAs | PB only | LN only |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | del11q | gain8(q13.3-q24.3)* del11(q14.1-q23.2)* del18(p11.32-p11.21)* |

gain2(p16.1-p15) (3Mb)§ | gain2(p25.3-p14) (64 Mb)§ del8(p23.3-p11.1) del9(p24.3-p13.1) del13(q14.2-q31.1) del13(q31.1) |

| 11 | tris12 | del4(q22.3-q23) del4(q31.3) del4(q32.2-q32.3) tris12 del18(q21.1-q21.2) del18(q21.2) del18(q21.31) |

- | - |

| 12 | del17p, del11q, del13q | del4(p15.2) del4(p15.1-p14) del4(p14-p12) del4(q13.1) del4(q13.1-q21.1) del4(q21.22) del4(q21.33-q22.11) gain6(p25.3-p24.2) del11(q22.2-q23.1) |

- | del3(p13) |

| 100 | del11q, del13q |

del6(q23.3-q24.1)* del 6(q24.2)* del 6(q24.2)* del11(q22.3) (0.3Mb)§ del13(q12.11) del13(q14.11) del13(q14.13-q14.3) del13(q14.3) |

del5(q14.3-q21.3) del11(q14.1-q23.3) (36Mb)§ |

|

| 101 | tris12, del13q | tris12 del13(q13.2-q14.3) |

- | - |

| 102 | neg | del8(p23.1)* | - | - |

| 103 | tris12 | tris12 | - | - |

| 104 | del13q | del13(q14.2-q14.3) | - | del6(q16.3-q26) |

| 106 | del13q | del13(q14.2-q14.3) | - | - |

previously reported in the literature

In Case100 and 10, two shared lesions were different in size among compartments, being larger in the LN compartment.

CNA, copy number aberration; PB, peripheral blood; LN, lymph node; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization

The inter-patient and intra-patient analyses revealed a high degree of heterogeneity according to the load and pattern of distribution of the genetic lesions among the two compartments (Fig. 1, Tables I and II). Notably, 6 of 9 cases (66.7%) showed a different clonal architecture of mutations and/or CNAs between the compartments, as described below.

Two cases showed a remarkable difference between the compartments: Case 10, with 6 LN-specific lesions, and Case 100, with 6 LN-specific and 8 PB-specific lesions, respectively. Both had unmutated IGHV rearrangements and belonged to the del(11q) hierarchical FISH category.

Case 10 showed 2 mutations (namely, DAPK1 and ZNF215) (Raval et al, 2007; Alders et al, 2000) and 4 CNAs (del8p23.3-p11.11, del9p24.3-p13.1, del13q14.2-q31.1 and del13q31.1) (Ouillette et al, 2011; Rinaldi et al, 2011; Chigrinova et al, 2013) that were LN-specific.

Case 100 had 5 mutations (SF3B1, C12orf71, KIF26B, POLR2A and WLS) (Messina et al, 2014; Quesada et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2011; Rossi et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2013; Fluiter et al, 2002; Augustin et al, 2012) and 1 CNA (del5q14.3-q21.3) that were found exclusively in the LN; one mutation (ABCC9) (Le Gallo et al, 2012) and 7 CNAs (del6q23.3-q24.1, 2 deletions of 6q24.2, del13q12.11, del13q14.11, del13q14.13-q14.3, del13q14.3) were PB-specific.

In addition, in these 2 cases, 2 of the shared CNAs were larger in the LN than in the PB (Supplementary Fig. 2A-B). In Case 10, a gain of chromosome 2p, described as a recurring aberration in untreated CLL at advanced stages (Rinaldi et al, 2011; Chigrinova et al, 2013; Forconi et al, 2008; Chapiro et al, 2010; Deambrogi et al, 2010), was 3 Mb in the PB (p16.1-p15) and 64 Mb in the LN (p25.3-p14).

Similarly, in Case 100, a deletion of 0.3 Mb on 11(q22.3) in the PB, which included 5 genes, one of which was ATM, was larger in the LN (36 Mb on 11(q14.1-q23.3) and characterized by the inclusion of BIRC3 (Rossi et al, 2012). This case carried also an ATM mutation in both compartments (Table I) (Guarini et al, 2012).

Four additional cases showed differences in the clonal genetic lesion between compartments, although at a lesser extent. Case 12 and Case 104 showed one CNA specific for the LN compartment, i.e. del(3p13) and del6(q16.3-q26), respectively, together with a common pattern of mutations. Case 11 and Case103 showed one mutation specific for the PB compartment, i.e. LGSN and MUC5B H3458Q, respectively (Nakatsugawa et al, 2009; Roy et al, 2014).

The remaining 3 cases (Cases 101, 102, 106) had a common clonal genetic lesion pattern between compartments.

There was no significant association between the patients’ clinico-biological features and the occurrence of PB- and/or LN-specific lesions. Nevertheless, all 4 cases with LN-specific lesions showed an unmutated IGHV status and 3 of the 4 cases carried high-risk FISH abnormalities (i.e. del17p and/or del11q) .

NGS approach for common and specific gene mutations

Forty-six of the 54 mutations identified by Sanger sequencing in both compartments underwent a deep-sequencing approach (coverage: 1000X) with the Genome Sequencer Junior instrument (454 Life Science, Roche Diagnostics), allowing a better definition and quantification of the clonal distribution of common mutations in the two compartments. Moreover, considering at least a 1.5-fold difference in VF between compartments, most (34, 75.5%) of the mutations showed no difference between PB and LN, 6 mutations were more represented in the LN compared to the PB and 6 were more commonly found in the PB than in the LN (Table I).

The 7 mutations identified as specific to the LN compartment were selected for an ultra-deep sequencing approach (10,000X coverage) in the corresponding PB compartment, in order to identify the presence of circulating subclones carrying the LN-specific mutations. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that 6 out of 7 LN mutations were present at a subclonal level in the PB with a VF between 0.5% and 5.3% (namely DAPK1, ZNF215, KIF26B, POLR2A, WLS and SF3B1), while 1 (C12orf71) was absent (Table I).

The same approach was used for 2 of the 3 mutations specifically found in the PB (LGSN was not tested for lack of material). Of these mutations, 1 (ABCC9) proved subclonal in the LN with a VF of 1.3% and 1 (MUC5B H3458Q) was absent in the LN.

Due to the limited sensitivity of the CNA method we could not exclude the presence of the compartment-specific aberrations at the subclonal level in the other compartment.

Relapses

During the study, 3 patients relapsed after treatment [Case 10 after fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab (FCR), Case 11 after FCR plus mitoxantrone, Case 100 after FC (2nd relapse) and FCR (3rd relapse)]. In 2 cases (Cases 10 and 100), the most informative ones, the pood availability of material enabled us to test the presence of the LN-specific mutations in the PB at subsequent relapses.

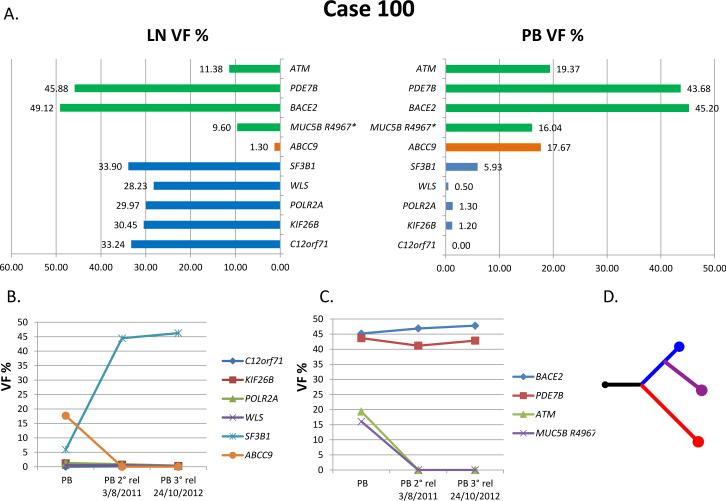

In Case 100, 4 of the 5 LN-specific mutations (C12orf71, KIF26B, POLR2A, WLS) were not found in the PB compartment by Sanger sequencing at two time-points subsequent to the study, corresponding to a 2nd and 3rd relapse occurring after 3 and 4 years from the 1st relapse, respectively. An ultra-deep sequencing approach, performed to quantify possible variations/increase in the amount of circulating subclones at relapses, showed a low VF indistinguishable from the background. In contrast, the LN-derived SF3B1 mutation became detectable by Sanger sequencing in the PB both at the 2nd and 3rd relapse, with an increase in VF from 5.3 to 44.46% and 46.26%, respectively (Fig. 2, Table III). Interestingly, the PB-specific mutation ABCC9, as well as the common ATM and MUC5B R4967* mutations, disappeared from the PB at the subsequent relapses.

Figure 2. Case 100.

(A) Pattern of mutations and VF per compartment at study. Green: common mutations; orange, PB-specific mutations; blue, LN-specific mutations. (B) and (C) PB at two subsequent relapses: VF of the LN-derived mutations (B) and of the common mutations (C). (D) Phylogenetic tree based on mutations and copy number aberrations (CNAs). Black represents common mutations and CNAs, red represents PB, blue represents LN, violet represents relapse.

VF, variant allele frequency; PB, peripheral blood; LN, lymph node; rel, relapse

Table III. Case 100 and Case 10.

Mutations and CNAs distribution in the PB and in the LN at the time of the study and in the PB at relapse.

| Case | Common lesions | Lesions in PB only | Lesions in LN only | Lesions in PB at relapse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 |

ATM

PDE7B BACE2 MUC5B R4967* |

ABCC9 |

C12orf71

KIF26B POLR2A SF3B1 WLS |

SF3B1

PDE7B BACE2 |

| del6(q23.3-q24.1) del 6(q24.2) del 6(q24.2) del11(q22.3) (0.3Mb)§ del13(q12.11) del13(q14.11) del13(q14.13-q14.3) del13(q14.3) |

del5(q14.3-q21.3) del11(q14.1-q23.3) (36Mb)§ |

del11(q22.1-q23.3) (19.448Mb)§ del13(q14.11-q14.3) del6(p22.3) |

||

| 10 |

PHKA2 L795H

PHKA2 V803F ADAMTS16 CEP250 ZNF536 COL22A1 SLC22A10 SPEN EGR2 RBMX TRPA1 |

DAPK1

ZNF215 |

ZNF215

PHKA2 L795H PHKA2 V803F ADAMTS16 CEP250 ZNF536 COL22A1 SLC22A10 SPEN EGR2 RBMX TRPA1 |

|

| gain8(q13.3-q24.3) del11(q14.1-q23.2) del18(p11.32-p11.21) |

gain2(p16.1-p15) (3Mb)§ | gain2(p25.3-p14) (64 Mb)§ del8(p23.3-p11.1) del9(p24.3-p13.1) del13(q14.2-q31.1) del13(q31.1) |

gain2(p25.3-p14) (64Mb)§, del3(p26.3-p25.3), gain3(p25.2-p25.1), gain5(p15.33-p14.1), del7(q21.12-q21.13), gain7(q21.13-q31.1), del7(q31.1-q31.2), gain7(q31.2), del7(q31.2-q32.1), gain7(q32.1-q32.3), del7(q32.3-q34), gain7(q34), gain7(q34-q36.1), del7(q36.1-q36.3), del8(p23.3-p11.1), gain8(q13.3-q24.3), del9(p24.3-p13.1), del11q(q14.1-q23.2), del13(q11-q12.11), del13(q12.2-q12.3), del13(q14.2-q34), gain17(q23.1-q25.3), del18(p11.32-p11.21) |

2 shared lesions were different in size among compartments, being larger in the LN compartment (see text).

CNAs in bold: newly acquired at relapse. Underlined lesions in the PB at relapse are those LN-derived.

CNA, copy number aberration; PB, peripheral blood; LN, lymph node

A remarkable contribution was provided by the CNA analysis. Indeed, in the 2nd relapse PB sample from Case 100, the size of del11(q22.1-q23.3) was larger (19.448 Mb, including 104 genes) than that previously detected in the PB (0.3 Mb on 11(q22.3) and included BIRC3, similar to the lesion documented in the LN (36 Mb (q14.1-q23.3) (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Moreover, in the PB at relapse, del(13) changed from two small lesions at q14.11 and q14.13-14.3 to a single lesion at q14.11-q14.3. In addition, a previously absent deletion at 6p22.3 appeared in the PB at relapse, whilst the previously identified del6(q23.3-q24.1), del6(q24.2), del6(q24.2) and del13(q12.11) disappeared. In contrast, the LN-specific lesion del5(q14.3-q21.3) was not found in the PB at relapse (Table III, Supplementary Table V).

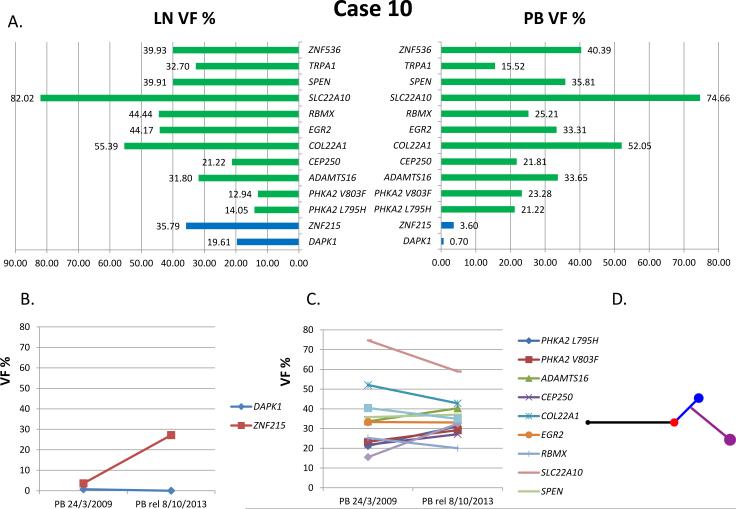

In the PB of Case 10 at a subsequent relapse occurring 4 years and 7 months after the 1st progression, treated with FCR, Sanger sequencing showed the clonal appearance of the LN-specific ZNF215 mutation (VF: 27.15%), with the DAPK1 mutation still absent (Fig. 3, Table III).

Figure 3. Case 10.

(A) Pattern of mutations and VF per compartment at study. Green: common mutations; blue, LN-specific mutations. (B) and (C) PB at a subsequent relapse: VF of the LN-derived mutations (B) and of the common mutations (C). (D) Phylogenetic tree based on mutations and copy number aberrations (CNAs). Black represents common mutations and CNAs, red represents PB, blue represents LN, violet represents relapse.

VF, variant allele frequency; PB, peripheral blood; LN, lymph node; rel, relapse

In addition, the LN-specific CNAs del8(p23.3-p11.1), del9(p24.3-p13.1) and gain2(p25.3-p14) (64Mb) appeared in the PB at relapse (Supplementary Fig. 2A). All the CNAs previously present in the PB were persistent at relapse, and 15 new CNAs were acquired (Table III, Supplementary Table V).

Discussion

The aim of this study - based on WES and analysis of CNAs - was to investigate the possible existence of a genomic difference between CLL cells from the LN compartment and those simultaneously circulating in the PB in patients with clinically relevant lymphadenopathy. In this respect, very few insights have been published (Herreros et al, 2010; Balogh et al, 2011; Cavazzini et al, 2012).

A leukaemic disease is expected to spread and steadily recirculate across the haematopoietic and lymphatic systems. However, given that the proliferating CLL cell burden is mainly localized within the LN and BM compartments (Schmid & Isaacson, 1994; Smit et al, 2007; van Gent et al, 2008; Herishanu et al, 2011; Calissano et al, 2011), it is reasonable to hypothesize that this is the site where the proliferating cells might accumulate genomic lesions, even with pathogenetic relevance.

In this study, we provided evidence that this might be the case. In fact, the majority (84.4%) of clonal mutations and most of the CNAs identified (65.8%) were shared between the two PB and LN compartments, as expected in a leukaemic disease and without significant frequency differences. Nevertheless, the PB and LN compartments carried different genomic lesions in 6 of 9 cases (66.7%), remarkably in 2 and to a lesser extent in 4. More specifically, 4 cases carried clonal mutations and/or CNAs in the LN compartment that were not found in the corresponding PB: Case 10, 2 mutations and 4 CNAs; Case 100, 5 mutations and 1 CNAs; Cases 12 and 104, 1 CNA each. Three cases carried PB-specific genetic lesions that were not identified in the LN compartment: Case 100, 1 mutation and 7 CNAs; Cases 11 and 103, 1 mutation each. In addition, it is worth highlighting that in 2 cases, CNAs were larger in the LN compared to the PB. We further dissected the mutational profile of the two compartments by an ultra-deep sequencing approach and proved the presence of circulating subclones carrying most of the “LN-specific” mutations (6/7, 85.7%), and the presence in the LN of 1/2 subclones carrying the PB-specific mutations. These evidences support the concept of the co-existence of CLL clones and subclones carrying a given genetic lesion in the same patient (Landau et al, 2013) and showed for the first time their different distribution according to the anatomical compartment.

In the two cases with the more remarkable differences among the compartments (Case 10 at 1st progression and Case 100, the only one studied at the time of 1st relapse after treatment), we investigated whether the LN-specific clones could spread out at a subsequent relapse, testing the PB in additional time points respect to the baseline study.

In Case 100, at 2nd relapse we documented the clonal espansion in the PB of the LN-specific SF3B1 mutation (5.93% vs >40%) and the disappearance of the PB-specific mutation (ABCC9). The clonal evolution of the disease is also witnessed by both the acquisition of new CNAs and the disappearance of previous CNAs. Interestingly, we also showed the presence of a larger del11q, which included BIRC3 deletion, as the one documented in the LN.

In Case 10, we documented in the PB at 1st relapse the clonal expansion of the LN-specific ZNF215 mutation and, more importantly, the appearance of the LN-specific CNAs del8(p23.3-p11.1), del9(p24.3-p13.1) and the change in size of gain2p, the latter having the same size as the one documented in the LN, together with the acquisition of new CNAs.

Thus, we provide the proof of principle that mutations and/or CNAs occurring in the LN can be positively selected by therapy and emerge and expand at disease relapse in the PB, probably according to their potential of driving the progression of the disease. In fact, SF3B1 mutation, BIRC3 deletion, del8(p23.3-p11.1), del9(p24.3-p13.1) and gain 2(p25.3-14) have been all consistently associated with adverse prognostic significance (Ouillette et al, 2011; Rinaldi et al, 2011; Chigrinova et al, 2013; Messina et al, 2014; Quesada et al, 2011; Wang et al, 2011; Rossi et al, 2011; Forconi et al, 2008; Chapiro et al, 2010; Deambrogi et al, 2010; Rossi et al, 2012).

In contrast, the PB-specific lesions appear to be more passenger than driver events: the 3 mutations (ABCC9, LGNS, MUC5B) have no known biological impact, confirmed by the disappearance of one of them at a subsequent relapse (ABCC9 in Case 100); the 7 CNAs, all found in Case 100, were either lost at relapse - del(6q) – or changed in size – del(13q), not displaying an adverse impact. They also could be expression of lesions arising in LN other than the biopsied one.

After the first reports demonstrating the presence of multiple CLL subclones within the same patient with different immunophenotypic and proliferative features (Damle et al, 2007; Calisssano et al 2009; Grubor et al, 2009), Schuh et al (2012), Landau et al (2013) and Ojha et al (2015) formally proved the intra-patient heterogeneity of CLL genomic features and elegantly suggested two models of disease progression: one is the clonal equilibrium, when the relative sizes of each subclone are mantained, and the other is the clonal evolution, in which some subclones emerge as dominant. Intrinsic factors, the administration of chemotherapy and microenvironmental stimuli affecting BCR signalling can theoretically condition the two scenarios, with therapy as the major trigger of clonal evolution (Ouillette et al, 2011; Gaidano et al, 2012; Puente & Lopez-Otin, 2013; Ojha et al, 2015). Similarly, our study provides first evidences on the role of the LN microenvironment as the potential site of origin of dominant clones in the dynamic evolution of CLL progression, according to the clonal evolution model, at least in two cases. In contrast, the three cases with genomic homogeneity according to the compartment reflect the recirculation of a leukaemic disease whose clonal equilibrium has not been yet modified by treatment (Landau et al, 2013; Ojha et al, 2015). Therefore, the fact that this is a cohort mainly composed of untreated patients could have underestimated the genomic heterogeneity between PB- and LN-derived CLL cells, whereas the emergence of unfavourable driver lesions in the LN compartment triggered by treatment could be more easily documented in patients in more advanced phases of disease, as shown in Case 100.

Given the importance of the epigenetic control of gene expression in CLL, mechanisms other than genetic lesions should also be considered. Although the global pattern of DNA methylation seems similar in CLL cells derived from LN compared to circulating cells (Cahill et al, 2013), a differential epigenetic control of gene expression according to the compartment has been suggested (Ferreira et al, 2014).

In conclusion, this study represents a snapshot of the genomic architecture of CLL cells from patients with lymphocytosis and significant LN enlargement. We showed an inter- and intra-patient clonal heterogeneity according to the compartment, with differences in mutations and CNAs between PB- and LN-derived CLL cells in most of the cases, which have a pathogenetic relevance, at least in some instances.

Our observations strengthen the role of CLL proliferation centres within the lymphatic tissues, where signals from the microenvironment and BCR signalling drive the expansion of the CLL clone (Herishanu et al, 2011). It has been recently demonstrated that the novel agent ibrutinib inhibits both BCR and NF-kB pathways in LN and BM resident cells of CLL patients (Herman et al, 2014). In addition to this antiproliferative activity, ibrutinib induces the mobilization of tissue-resident cells into the blood, thus removing CLL cells from this nurturing milieu, triggering a rapid LN shrinkage and a transient lymphocytosis (Burger & Montserrat, 2013). This effect has been linked in vivo to the inhibition of the BTK and VLA4-mediated CLL cell adhesion (Herman et al, 2015). It will be of interest to identify whether the CLL cell redistribution from the LN to the PB compartment determines either an early and more dramatic appearance of CLL molecular lesions derived from the LN in the PB compartment or the “disruption” of the niche where minor and chemoresistant subclones can arise, interfering with a potential long-term clonal evolution.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Francesca Dal Pero (Roche Diagnostics) for NGS technical advice and Anthony B. Holmes for contribution in CNA analysis. This work was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Special Program Molecular Clinical Oncology, 5 × 1000, No. 10007, Milan, Italy (to RF and GG); NIH funding 1U54 CA121852-05; R01NS061776; 1R01CA185486-01; 1R01CA179044-01A1, Stewart Foundation (to RR); My First AIRC Grant No. 13470, AIRC Foundation Milan, Italy (to DR); Fondazione Cariplo, Grant No. 2012-0689 (to DR and GG); Progetto Giovani Ricercatori 2010, Grant No. GR-2010-2317594, Ministero della Salute, Rome, Italy (to DR); Compagnia di San Paolo, Grant No. PMN_call_2012_0071, Turin, Italy (DR and GG); Futuro in Ricerca 2012 Grant No. RBFR12D1CB, Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca, Rome, Italy (to DR).

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Authorship Contributions

IDG designed the study, analysed the results and wrote the paper; MMarinelli, CI, LC and SR performed and analysed Sanger sequencing and NGS experiments; JW and RR performed the bioinformatic analysis of WES and ultra-deep NGS and revised the manuscript; SB performed and analysed the CNA study; MMessina performed and analysed the Sanger sequencing validation and the CNA study; SC supervized the WES experiments and revise the manuscript; FRM provided samples and clinical assistance; VDM managed sample collection and storage; MSDP performed immunophenotype; MN performed FISH analysis; CC performed ultra-deep NGS experiments; DR analysed and supervized ultra-deep NGS, contributed to design the study and revise the manuscript, GG and AG contributed to design the study and revise the manuscript; RF designed the study, analysed and discussed the results, and critically revised the manuscript.

Supplementary information is available at the British Journal of Haematology's website.

References

- Alders M, Ryan A, Hodges M, Bliek J, Feinberg AP, Privitera O, Westerveld A, Little PF, Mannens M. Disruption of a novel imprinted zinc-finger gene, ZNF215, in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2000;66:1473–1484. doi: 10.1086/302892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustin I, Goidts V, Bongers A, Kerr G, Vollert G, Radlwimmer B, Hartmann C, Herold-Mende C, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Boutros M. The Wnt secretion protein Evi/Gpr177 promotes glioma tumourigenesis. EMBO Molecular Medicine. 2012;4:38–51. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201100186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balogh Z, Reiniger L, Rajnai H, Csomor J, Szepesi A, Balogh A, Deák L, Gagyi E, Bödör C, Matolcsy A. High rate of neoplastic cells with genetic abnormalities in proliferation centers of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2011;52:1080–1084. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.555889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger JA, Gribben JG. The microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other B cell malignancies: insight into disease biology and new targeted therapies. Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2014;24:71–81. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger JA, Montserrat E. Coming full circle: 70 years of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell redistribution, from glucocorticoids to inhibitors of B cell receptor signaling. Blood. 2013;121:1501–1509. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-452607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill N, Bergh AC, Kanduri M, Göransson-Kultima H, Mansouri L, Isaksson A, Ryan F, Smedby KE, Juliusson G, Sundström C, Rosén A, Rosenquist R. 450K-array analysis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells reveals global DNA methylation to be relatively stable over time and similar in resting and proliferative compartments. Leukemia. 2013;27:150–158. doi: 10.1038/leu.2012.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caligaris-Cappio F, Ghia P. Novel insights in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: are we getting closer to understanding the pathogenesis of the disease? Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2008;26:4497–4503. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.4393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calissano C, Damle RN, Hayes G, Murphy EJ, Hellerstein MK, Moreno C, Sison C, Kaufman MS, Kolitz JE, Allen SL, Rai KR, Chiorazzi N. In vivo intraclonal and interclonal kinetic heterogeneity in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2009;114:4832–4842. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calissano C, Damle RN, Marsilio S, Yan XJ, Yancopoulos S, Hayes G, Emson C, Murphy EJ, Hellerstein MK, Sison C, Kaufman MS, Kolitz JE, Allen SL, Rai KR, Ivanovic I, Dozmorov IM, Roa S, Scharff MD, Li W, Chiorazzi N. Intraclonal complexity in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: fractions enriched in recently born/divided and older/quiescent cells. Molecular Medicine. 2011;17:1374–1382. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2011.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavazzini F, Rizzotto L, Sofritti O, Daghia G, Cibien F, Martinelli S, Ciccone M, Saccenti E, Dabusti M, Elkareem AA, Bardi A, Tammiso E, Cuneo A, Rigolin GM. Clonal evolution including 14q32/IGH translocations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: analysis of clinicobiologic correlations in 105 patients. Leukemia Lymphoma. 2012;53:83–88. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2011.606384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapiro E, Leporrier N, Radford-Weiss I, Bastard C, Mossafa H, Leroux D, Tigaud I, De Braekeleer M, Terré C, Brizard F, Callet-Bauchu E, Struski S, Veronese L, Fert-Ferrer S, Taviaux S, Lesty C, Davi F, Merle-Béral H, Bernard OA, Sutton L, Raynaud SD, Nguyen-Khac F. Gain of the short arm of chromosome 2 (2p) is a frequent recurring chromosome aberration in untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) at advanced stages. Leukemia Research. 2010;34:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2009.03.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chigrinova E, Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Rossi D, Rancoita PM, Strefford JC, Oscier D, Stamatopoulos K, Papadaki T, Berger F, Young KH, Murray F, Rosenquist R, Greiner TC, Chan WC, Orlandi EM, Lucioni M, Marasca R, Inghirami G, Ladetto M, Forconi F, Cogliatti S, Votavova H, Swerdlow SH, Stilgenbauer S, Piris MA, Matolcsy A, Spagnolo D, Nikitin E, Zamò A, Gattei V, Bhagat G, Ott G, Zucca E, Gaidano G, Bertoni F. Two main genetic pathways lead to the transformation of chronic lymphocytic leukemia to Richter syndrome. Blood. 2013;122:2673–2682. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-489518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiorazzi N, Rai KR, Ferrarini M. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2005;352:804–815. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra041720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damle RN, Temburni S, Calissano C, Yancopoulos S, Banapour T, Sison C, Allen SL, Rai KR, Chiorazzi N. CD38 expression labels an activated subset within chronic lymphocytic leukemia clones enriched in proliferating B cells. Blood. 2007;110:3352–3359. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deambrogi C, De Paoli L, Fangazio M, Cresta S, Rasi S, Spina V, Gattei V, Gaidano G, Rossi D. Analysis of the REL, BCL11A, and MYCN proto-oncogenes belonging to the 2p amplicon in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. American Journal of Hematology. 2010;85:541–544. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Giudice I, Mauro FR, De Propris MS, Santangelo S, Marinelli M, Peragine N, Di Maio V, Nanni M, Barzotti R, Mancini F, Armiento D, Paoloni F, Guarini A, Foà R. White blood cell count at diagnosis and immunoglobulin variable region gene mutations are independent predictors of treatment-free survival in young patients with stage A chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2011;96:626–630. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2010.028779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri G, Rasi S, Rossi D, Trifonov V, Khiabanian H, Ma J, Grunn A, Fangazio M, Capello D, Monti S, Cresta S, Gargiulo E, Forconi F, Guarini A, Arcaini L, Paulli M, Laurenti L, Larocca LM, Marasca R, Gattei V, Oscier D, Bertoni F, Mullighan CG, Foá R, Pasqualucci L, Rabadan R, Dalla-Favera R, Gaidano G. Analysis of the chronic lymphocytic leukemia coding genome: role of NOTCH1 mutational activation. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208:1389–1401. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira PG, Jares P, Rico D, Gómez-López G, Martínez-Trillos A, Villamor N, Ecker S, González-Pérez A, Knowles DG, Monlong J, Johnson R, Quesada V, Djebali S, Papasaikas P, López-Guerra M, Colomer D, Royo C, Cazorla M, Pinyol M, Clot G, Aymerich M, Rozman M, Kulis M, Tamborero D, Gouin A, Blanc J, Gut M, Gut I, Puente XS, Pisano DG, Martin-Subero JI, López-Bigas N, López-Guillermo A, Valencia A, López-Otín C, Campo E, Guigó R. Transcriptome characterization by RNA sequencing identifies a major molecular and clinical subdivision in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Genome Research. 2014;24:212–226. doi: 10.1101/gr.152132.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluiter K, ten, Asbroek AL, van Groenigen M, Nooij M, Aalders MC, Baas F. Tumor genotype-specific growth inhibition in vivo by antisense oligonucleotides against a polymorphic site of the large subunit of human RNA polymerase II. Cancer Research. 2002;62:2024–2028. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foà R, Del Giudice I, Guarini A, Rossi D, Gaidano G. Clinical implications of the molecular genetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Haematologica. 2013;98:675–685. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.069369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forconi F, Rinaldi A, Kwee I, Sozzi E, Raspadori D, Rancoita PM, Scandurra M, Rossi D, Deambrogi C, Capello D, Zucca E, Marconi D, Bomben R, Gattei V, Lauria F, Gaidano G, Bertoni F. Genome-wide DNA analysis identifies recurrent imbalances predicting outcome in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia with 17p deletion. British Journal of Haematology. 2008;143:532–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaidano G, Foà R, Dalla-Favera R. Molecular pathogenesis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122:3432–3438. doi: 10.1172/JCI64101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grubor V, Krasnitz A, Troge JE, Meth JL, Lakshmi B, Kendall JT, Yamrom B, Alex G, Pai D, Navin N, Hufnagel LA, Lee YH, Cook K, Allen SL, Rai KR, Damle RN, Calissano C, Chiorazzi N, Wigler M, Esposito D. Novel genomic alterations and clonal evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia revealed by representational oligonucleotide microarray analysis (ROMA). Blood. 2009;113:1294–1303. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guarini A, Marinelli M, Tavolaro S, Bellacchio E, Magliozzi M, Chiaretti S, De Propris MS, Peragine N, Santangelo S, Paoloni F, Nanni M, Del Giudice I, Mauro FR, Torrente I, Foà R. ATM gene alterations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients induce a distinct gene expression profile and predict disease progression. Haematologica. 2012;97:47–55. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.049270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallek M, Cheson BD, Catovsky D, Caligaris-Cappio F, Dighiero G, Döhner H, Hillmen P, Keating MJ, Montserrat E, Rai KR, Kipps TJ, International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute-Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood. 2008;112:5259–5269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-093906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herishanu Y, Pérez-Galán P, Liu D, Biancotto A, Pittaluga S, Vire B, Gibellini F, Njuguna N, Lee E, Stennett L, Raghavachari N, Liu P, McCoy JP, Raffeld M, Stetler-Stevenson M, Yuan C, Sherry R, Arthur DC, Maric I, White T, Marti GE, Munson P, Wilson WH, Wiestner A. The lymph node microenvironment promotes B-cell receptor signaling, NF-kappaB activation, and tumor proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;117:563–574. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-05-284984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman SE, Mustafa RZ, Gyamfi JA, Pittaluga S, Chang S, Chang B, Farooqui M, Wiestner A. Ibrutinib inhibits BCR and NF-κB signaling and reduces tumor proliferation in tissue-resident cells of patients with CLL. Blood. 2014;123:3286–3295. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-02-548610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herman SE, Mustafa RZ, Jones J, Wong DH, Farooqui M, Wiestner A. Treatment with ibrutinib inhibits BTK and VLA-4 dependent adhesion of chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells in vivo. Clinical Cancer Research. 2015 2015 Jun 18; doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0781. [Epub ahead of print] doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-0781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herreros B, Rodríguez-Pinilla SM, Pajares R, Martínez-Gónzalez MA, Ramos R, Munoz I, Montes-Moreno S, Lozano M, Sánchez-Verde L, Roncador G, Sánchez-Beato M, de Otazu RD, Pérez-Guillermo M, Mestre MJ, Bellas C, Piris MA. Proliferation centers in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: the niche where NF-kappaB activation takes place. Leukemia. 2010;24:872–876. doi: 10.1038/leu.2009.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal-Hanjani M, Quezada SA, Larkin J, Swanton C. Translational implications of tumor heterogeneity. Clinical Cancer Research. 2015;21:1258–1266. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landau DA, Carter SL, Stojanov P, McKenna A, Stevenson K, Lawrence MS, Sougnez C, Stewart C, Sivachenko A, Wang L, Wan Y, Zhang W, Shukla SA, Vartanov A, Fernandes SM, Saksena G, Cibulskis K, Tesar B, Gabriel S, Hacohen N, Meyerson M, Lander ES, Neuberg D, Brown JR, Getz G, Wu CJ. Evolution and impact of subclonal mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2013;152:714–726. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Gallo M, O'Hara AJ, Rudd ML, Urick ME, Hansen NF, O'Neil NJ, Price JC, Zhang S, England BM, Godwin AK, Sgroi DC, NIH Intramural Sequencing Center (NISC) Comparative Sequencing Program. Hieter P, Mullikin JC, Merino MJ, Bell DW. Exome sequencing of serous endometrial tumors identifies recurrent somatic mutations in chromatin-remodeling and ubiquitin ligase complex genes. Nature Genetics. 2012;44:1310–1315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messina M, Del Giudice I, Khiabanian H, Rossi D, Chiaretti S, Rasi S, Spina V, Holmes AB, Marinelli M, Fabbri G, Piciocchi A, Mauro FR, Guarini A, Gaidano G, Dalla-Favera R, Pasqualucci L, Rabadan R, Foà R. Genetic lesions associated with chronic lymphocytic leukemia chemo-refractoriness. Blood. 2014;123:2378–2388. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-534271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messmer BT, Messmer D, Allen SL, Kolitz JE, Kudalkar P, Cesar D, Murphy EJ, Koduru P, Ferrarini M, Zupo S, Cutrona G, Damle RN, Wasil T, Rai KR, Hellerstein MK, Chiorazzi N. In vivo measurements document the dynamic cellular kinetics of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;115:755–764. doi: 10.1172/JCI23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakatsugawa M, Hirohashi Y, Torigoe T, Asanuma H, Takahashi A, Inoda S, Kiriyama K, Nakazawa E, Harada K, Takasu H, Tamura Y, Kamiguchi K, Shijubo N, Honda R, Nomura N, Hasegawa T, Takahashi H, Sato N. Novel spliced form of a lens protein as a novel lung cancer antigen, Lengsin splicing variant 4. Cancer Science. 2009;100:1485–1493. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01187.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha J, Ayres J, Secreto C, Tschumper R, Rabe K, Van Dyke D, Slager S, Shanafelt T, Fonseca R, Kay NE. Deep sequencing identifies genetic heterogeneity and recurrent convergent evolution in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125:492–498. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-06-580563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouillette P, Collins R, Shakhan S, Li J, Peres E, Kujawski L, Talpaz M, Kaminski M, Li C, Shedden K, Malek SN. Acquired genomic copy number aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2011;118:3051–3061. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-327858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DW, Li M, Zhang X, Jones S, Leary RJ, Lin JC, Boca SM, Carter H, Samayoa J, Bettegowda C, Gallia GL, Jallo GI, Binder ZA, Nikolsky Y, Hartigan J, Smith DR, Gerhard DS, Fults DW, VandenBerg S, Berger MS, Marie SK, Shinjo SM, Clara C, Phillips PC, Minturn JE, Biegel JA, Judkins AR, Resnick AC, Storm PB, Curran T, He Y, Rasheed BA, Friedman HS, Keir ST, McLendon R, Northcott PA, Taylor MD, Burger PC, Riggins GJ, Karchin R, Parmigiani G, Bigner DD, Yan H, Papadopoulos N, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, Velculescu VE. The genetic landscape of the childhood cancer medulloblastoma. Science. 2011;331:435–439. doi: 10.1126/science.1198056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Trifonov V, Fabbri G, Ma J, Rossi D, Chiarenza A, Wells VA, Grunn A, Messina M, Elliot O, Chan J, Bhagat G, Chadburn A, Gaidano G, Mullighan CG, Rabadan R, Dalla-Favera R. Analysis of the coding genome of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Nature Genetics. 2011;43:830–837. doi: 10.1038/ng.892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puente XS, López-Otín C. The evolutionary biography of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2013;45:229–231. doi: 10.1038/ng.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesada V, Conde L, Villamor N, Ordóñez GR, Jares P, Bassaganyas L, Ramsay AJ, Beà S, Pinyol M, Martínez-Trillos A, López-Guerra M, Colomer D, Navarro A, Baumann T, Aymerich M, Rozman M, Delgado J, Giné E, Hernández JM, González-Díaz M, Puente DA, Velasco G, Freije JM, Tubío JM, Royo R, Gelpí JL, Orozco M, Pisano DG, Zamora J, Vázquez M, Valencia A, Himmelbauer H, Bayés M, Heath S, Gut M, Gut I, Estivill X, López-Guillermo A, Puente XS, Campo E, López-Otín C. Exome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations of the splicing factor SF3B1 gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Nature Genetics. 2011;44:47–52. doi: 10.1038/ng.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval A, Tanner SM, Byrd JC, Angerman EB, Perko JD, Chen SS, Hackanson B, Grever MR, Lucas DM, Matkovic JJ, Lin TS, Kipps TJ, Murray F, Weisenburger D, Sanger W, Lynch J, Watson P, Jansen M, Yoshinaga Y, Rosenquist R, de Jong PJ, Coggill P, Beck S, Lynch H, de la Chapelle A, Plass C. Downregulation of death-associated protein kinase 1 (DAPK1) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cell. 2007;129:879–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi A, Mian M, Kwee I, Rossi D, Deambrogi C, Mensah AA, Forconi F, Spina V, Cencini E, Drandi D, Ladetto M, Santachiara R, Marasca R, Gattei V, Cavalli F, Zucca E, Gaidano G, Bertoni F. Genome-wide DNA profiling better defines the prognosis of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. British Journal of Haematology. 2011;154:590–599. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08789.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Bruscaggin A, Spina V, Rasi S, Khiabanian H, Messina M, Fangazio M, Vaisitti T, Monti S, Chiaretti S, Guarini A, Del Giudice I, Cerri M, Cresta S, Deambrogi C, Gargiulo E, Gattei V, Forconi F, Bertoni F, Deaglio S, Rabadan R, Pasqualucci L, Foà R, Dalla-Favera R, Gaidano G. Mutations of the SF3B1 splicing factor in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: association with progression and fludarabinerefractoriness. Blood. 2011;118:6904–6908. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi D, Fangazio M, Rasi S, Vaisitti T, Monti S, Cresta S, Chiaretti S, Del Giudice I, Fabbri G, Bruscaggin A, Spina V, Deambrogi C, Marinelli M, Famà R, Greco M, Daniele G, Forconi F, Gattei V, Bertoni F, Deaglio S, Pasqualucci L, Guarini A, Dalla-Favera R, Foà R, Gaidano G. Disruption of BIRC3 associates with fludarabine chemorefractoriness in TP53 wild-type chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2012;119:2854–2862. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-12-395673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, Alexander SN, Bellinghausen LK, Song AS, Petrova YM, Tuvim MJ, Adachi R, Romo I, Bordt AS, Bowden MG, Sisson JH, Woodruff PG, Thornton DJ, Rousseau K, De la Garza MM, Moghaddam SJ, Karmouty-Quintana H, Blackburn MR, Drouin SM, Davis CW, Terrell KA, Grubb BR, O'Neal WK, Flores SC, Cota-Gomez A, Lozupone CA, Donnelly JM, Watson AM, Hennessy CE, Keith RC, Yang IV, Barthel L, Henson PM, Janssen WJ, Schwartz DA, Boucher RC, Dickey BF, Evans CM. Muc5b is required for air way defence. Nature. 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid C, Isaacson PG. Proliferation centres in B-cell malignant lymphoma, lymphocytic (B-CLL): an immunophenotypic study. Histopathology. 1994;24:445–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1994.tb00553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuh A, Becq J, Humphray S, Alexa A, Burns A, Clifford R, Feller SM, Grocock R, Henderson S, Khrebtukova I, Kingsbury Z, Luo S, McBride D, Murray L, Menju T, Timbs A, Ross M, Taylor J, Bentley D. Monitoring chronic lymphocytic leukemia progression by whole genome sequencing reveals heterogeneous clonal evolution patterns. Blood. 2012;120:4191–4196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-433540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit LA, Hallaert DY, Spijker R, de Goeij B, Jaspers A, Kater AP, van Oers MH, van Noesel CJ, Eldering E. Differential Noxa/Mcl-1 balance in peripheral versus lymph node chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells correlates with survival capacity. Blood. 2007;109:1660–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-05-021683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifonov V, Pasqualucci L, Tiacci E, Falini B, Rabadan R. SAVI: a statistical algorithm for variant frequency identification. BMC Systems Biology. 2013;7(Suppl 2):S2. doi: 10.1186/1752-0509-7-S2-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Gent R, Kater AP, Otto SA, Jaspers A, Borghans JA, Vrisekoop N, Ackermans MA, Ruiter AF, Wittebol S, Eldering E, van Oers MH, Tesselaar K, Kersten MJ, Miedema F. In vivo dynamics of stable chronic lymphocytic leukemia inversely correlate with somatic hypermutation levels and suggest no major leukemic turnover in bone marrow. Cancer Research. 2008;68:10137–10144. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Lawrence MS, Wan Y, Stojanov P, Sougnez C, Stevenson K, Werner L, Sivachenko A, DeLuca DS, Zhang L, Zhang W, Vartanov AR, Fernandes SM, Goldstein NR, Folco EG, Cibulskis K, Tesar B, Sievers QL, Shefler E, Gabriel S, Hacohen N, Reed R, Meyerson M, Golub TR, Lander ES, Neuberg D, Brown JR, Getz G, Wu CJ. SF3B1 and other novel cancer genes in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2011;365:2497–2506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Zhao B, Wang G, Hui Z, Wang MH, Pan JF, Zheng H. High expression of KIF26B in breast cancer associates with poor prognosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e61640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.