Abstract

Background

Data comparing patient experiences between general medicine teaching and non-teaching hospitalist services are lacking.

Objective

Evaluate hospitalized patients’ experience on a general medicine teaching and non-teaching hospitalist services by assessing patients’ confidence in their ability to identify their physician(s), understand their roles, and their rating of the coordination and overall care.

Methods

Retrospective cohort analysis of general medicine teaching and non-teaching hospitalist services from 2007 to 2013 at an academic medical center. Patients were surveyed 30-days after hospital discharge regarding their confidence in their ability to identify their physician(s), understand the role of their physician(s), and their perceptions of coordination, and overall care. A 3-level, mixed effects logistic regression was performed to ascertain the association between service-type and patient-reported outcomes.

Results

Data from 4,591 general medicine teaching and 1,811 non-teaching hospitalist service patients demonstrated that those cared for by the hospitalist service were more likely to report being able to identify their physician (50% vs. 45%, p<0.001), understand their role (54% vs. 50%, p<0.001), and rate greater satisfaction with coordination (68 vs. 64%, p=0.006) and overall care (73% vs. 67%, p<0.001). In regression models, the hospitalist service was associated with higher ratings in overall care (OR 1.33; 95% CI 1.15-1.47), even when hospitalists were the attendings on general medicine teaching services (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.01-1.31).

Conclusion

Patients on a non-teaching hospitalist service rated their overall care slightly better than patients on a general medicine teaching service. Team structure and complexity may play a role in this difference.

Keywords: Patient Experience, Patient Satisfaction, Medical Education, Patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

The hospitalized patient experience has become an area of increased focus for hospitals given the recent coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.1 While patient experiences are multifactorial, one component is the relationship that hospitalized patients developed with their inpatient physicians. In recognition of the importance of this relationship, several organizations including Society of Hospital Medicine, Society of General Internal Medicine, American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have recommended that patients know and understand who is guiding their care at all times during their hospitalization.2,3 Unfortunately, previous studies have shown that hospitalized patients often lack the ability to identify4,5 and understand their course of care.6,7 This may be due to numerous clinical factors including lack of a prior relationship, rapid pace of clinical care, and the frequent transitions of care found in both hospitalists and general medicine teaching services.5,8,9 Regardless of the cause, one could hypothesize that patients who are unable to identify or understand the role of their physician may be less informed about their hospitalization, which may lead to further confusion, dissatisfaction, and ultimately a poor experience.

Given the proliferation of non-teaching hospitalist services in teaching hospitals, it is important to understand if patient experiences differ between general medicine teaching and hospitalist services. Several reasons could explain why patient experiences may vary on these services. For example, patients on a hospitalist service will likely interact with a single physician caretaker, which may give a feeling of more personalized care. In contrast, patients on general medicine teaching services are cared for by larger teams of residents under the supervision of an attending physician. Residents are also subjected to duty-hour restrictions, clinic responsibilities, and other educational requirements that may impede the continuity of care for hospitalized patients.10–12 While one study has shown that hospitalist-intensive hospitals perform better on patient satisfaction measures,13 no study to date has compared patient-reported experiences on general medicine teaching and non-teaching hospitalist services. This study aims to evaluate the hospitalized patient experience on both teaching and non-teaching hospitalist services by assessing several patient-reported measures of their experience, namely their confidence in their ability to identify their physician(s), understand their roles, and their rating of both the coordination and overall care.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis at the University of Chicago Medical Center between July 2007 and June 2013. Data were acquired as part of the Hospitalist Project, an ongoing study that is used to evaluate the impact of hospitalists, and now serves as infrastructure to continue research related to hospital care at University of Chicago.14 Patients were cared for by either the general medicine teaching service or the non-teaching hospitalist service. General medicine teaching services were composed of an attending physician who rotates for 2-weeks at a time, a 2nd or 3rd year medicine resident, 1-2 medicine interns, and 1-2 medical students.15 The attending physician assigned to the patient's hospitalization was the attending listed on the first day of hospitalization, regardless of the length of hospitalization. Non-teaching hospitalist services consisted of a single hospitalist who work 7-day shifts, and are assisted by a Nurse-Practitioner/Physician's Assistant (NPA). The majority of attendings on the hospitalist service were less than 5 years out of residency. Both services admitted 7-days a week, with patients initially admitted to the general medicine teaching service until resident caps were met, after which all subsequent admissions were admitted to the hospitalist service. In addition, the hospitalist service is also responsible for specific patient sub-populations, such as lung and renal transplants, and oncologic patients who have previously established care with our institution.

Data Collection

During a 30-day post-hospitalization follow-up questionnaire, patients were surveyed regarding their confidence in their ability to identify and understand the roles of their physician(s) and their perceptions of the overall coordination of care and their overall care, using a 5-point Likert scale (1, poor understanding, to 5, excellent understanding). Questions related to satisfaction with care and coordination were derived from the Picker-Commonwealth Survey, a previously validated survey meant to evaluate patient-centered care16. Patients were also asked to report their race, level of education, comorbid diseases, and whether they had any prior hospitalizations within 1-year. Chart review was performed to obtain patient age, gender, and hospital length of stay (LOS), and calculated Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)17. Patients with missing data or responses to survey questions were excluded from final analysis. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written consented prior to participation.

Data Analysis

After initial analysis noted that outcomes were skewed, the decision was made to dichotomize the data and use logistic rather than linear regression models. Patient responses to the follow-up phone questionnaire were dichotomized to reflect the top 2 categories (“Excellent” and “Very Good”). Pearson chi-square analysis was used to assess for any differences in demographic characteristics, disease severity, and measures of patient experience between the two services. To assess if service type was associated with differences in our four measures of patient experience, we created a 3-level mixed-effects logistic regression using a logit function while controlling for age, gender, race, CCI, LOS, previous hospitalizations within 1 year, level of education, and academic year. These models studied the longitudinal association between teaching service and the four outcome measures while also controlling for the cluster effect of time nested within individual patients, who were clustered within physicians. The model included random intercepts at both the patient- and physician-level and also included a random-effect of service (teaching vs. non-teaching) at the patient-level. A Hausman test was used to determine if these random-effects models improved fit over a fixed-effects model, and the intraclass correlations were compared using likelihood-ratio tests to determine the appropriateness of a 3-level vs. 2-level model. Data management and chi-square analyses were performed using Stata Version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and mixed-effects regression models were done in SuperMix (Scientific Software International, Skokie, IL).

RESULTS

In total, 14,855 patients were enrolled during their hospitalization with 57% and 61% completing the 30-day follow-up survey on the hospitalist and general medicine teaching service, respectively. In total, 4,131 (69%) and 4,322 (48%) of the hospitalist and general medicine services, respectively, either did not answer all survey questions, or were missing basic demographic data, thus were excluded. Data from 4,591 patients on the general medicine teaching (52% of those enrolled at hospitalization), and 1,811 on the hospitalist service (31% of those enrolled at hospitalization) were used for final analysis (Figure 1). Respondents were predominantly female (61 and 56%), African American (75 and 63%) with mean age of 56.2 (± 19.4) and 57.1 (±16.1), for the general medicine teaching and hospitalist services, respectively. A majority of patients (71 and 66%) had a CCI of 0-3 on both services. There were differences in self-reported comorbidities between the two-groups, with hospitalist services having a higher prevalence of cancer (20 vs. 7%), renal (25 vs. 18%), and liver disease (23 vs. 7%). Patients on the hospitalist service had a longer mean LOS (5.5 vs. 4.8), a greater percentage of a hospitalization within 1-year (58 vs. 52%), and a larger proportion who were admitted in 2011-2013 compared to 2007-2010 (75 vs. 39%), when compared to the general medicine teaching services. Median LOS and interquartile ranges were similar between both groups. While most baseline demographics were statistically different between the two groups (Table 1), these differences were likely clinically insignificant. Compared to those that responded to the follow-up survey, non-responders were more likely to be African American (73 and 64%, p<0.001), and female (60 and 56%, p<0.01). While the nonresponders were more likely to be hospitalized in the past 1-year (62 and 53%, p<0.001) and have a lower CCI [CCI 0-3 (75 and 80%, p<0.001)] compared to responders. Demographics between responders and non-responders were also statistically different from one another.

Figure 1.

Study design and exclusion criteria

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics.

| Variable | General Medicine Teaching | Non-teaching Hospitalist | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 4,591 | 1,811 | <0.001 |

| Attending Classification, n (%) | |||

| Hospitalist | 1,147 (25) | 1,811 (100) | |

| Response Rate (%) | 61 | 57 | <0.01 |

| Age, years (mean ±SD) | 56.2 ± 19.4 | 57.1 ± 16.1 | <0.01 |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Male | 1,796 (39) | 805 (44) | |

| Female | 2,795 (61) | 1,004 (56) | |

| Race, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| African-American | 3,440 (75) | 1,092 (63) | |

| White | 900 (20) | 571 (32) | |

| Asian/Pacific | 38 (1) | 17 (1) | |

| Other | 20 (1) | 10 (1) | |

| Unknown | 134 (3) | 52 (3) | |

| Charlson-Comorbidity Index, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1,635 (36) | 532 (29) | |

| 1-2 | 1,590 (35) | 675 (37) | |

| 3-9 | 1,366 (30) | 602 (33) | |

| Self-reported Comorbidities | |||

| Anemia/Sickle Cell Disease | 1,201 (26) | 408 (23) | 0.003 |

| Asthma/COPD | 1,251 (28) | 432 (24) | 0.006 |

| Cancer* | 300 (7) | 371 (20) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1,035 (23) | 411 (23) | 0.887 |

| Diabetes | 1,381 (30) | 584 (32) | 0.087 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1,140 (25) | 485 (27) | 0.104 |

| Cardiac | 1,336 (29) | 520 (29) | 0.770 |

| Hypertension | 2,566 (56) | 1,042 (58) | 0.222 |

| HIV/AIDS | 151 (3) | 40 (2) | 0.022 |

| Kidney Disease | 828 (18) | 459 (25) | <0.001 |

| Liver Disease | 313 (7) | 417 (23) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 543 (12) | 201 (11) | 0.417 |

| Education Level | 0.066 | ||

| High School | 2,248 (49) | 832 (46) | |

| Junior College/College | 1,878 (41) | 781 (43) | |

| Post-graduate | 388 (8) | 173 (10) | |

| Don't know | 77 (2) | 23 (1) | |

| Academic Year, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| July 2007 – June 2008 | 938 (20) | 90 (5) | |

| July 2008 – June 2009 | 702 (15) | 148 (8) | |

| July 2009 – June 2010 | 576(13) | 85 (5) | |

| July 2010 – June 2011 | 602 (13) | 138 (8) | |

| July 2011 – June 2012 | 769 (17) | 574 (32) | |

| July 2012 – June 2013 | 1,004 (22) | 774 (43) | |

| Length of Stay (days, mean ±SD) | 4.8 (±7.3) | 5.5 (±6.4) | <0.01 |

| Prior Hospitalization, n (%) (within1-year) | Yes: 2,379 (52) | Yes: 1,039 (58) | <0.01 |

NOTE: SD, standard deviation

Cancer diagnosis within previous 3-years

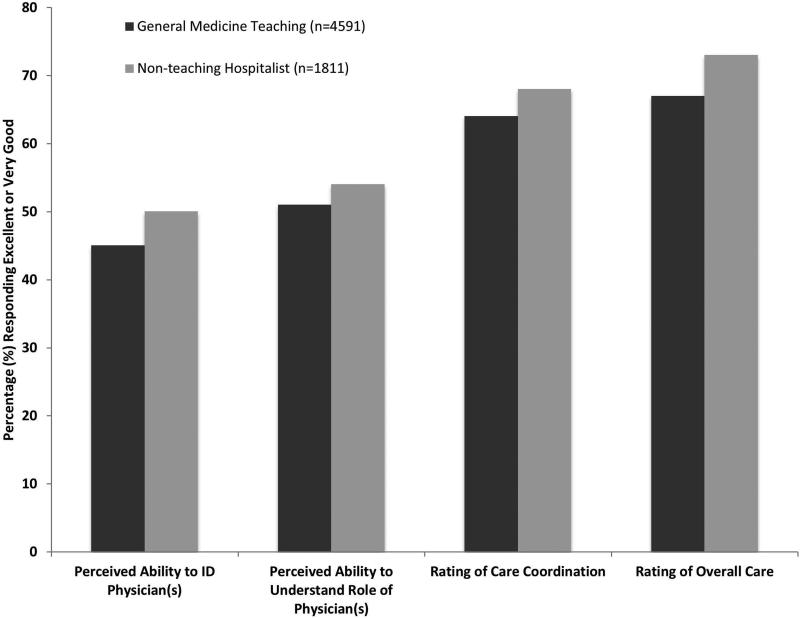

Unadjusted results revealed that patients on the hospitalist service were more confident in their abilities to identify their physician(s) (50% vs. 45%, p<0.001), perceived greater ability in understanding the role of their physician(s) (54% vs. 50%, p<0.001), and reported greater satisfaction with coordination and teamwork (68 vs. 64%, p=0.006), and with overall care (73% vs. 67%, p<0.001) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Unadjusted patient experience responses

From the mixed-effects regression models it was discovered that admission to the hospitalist service was associated with a higher odds ratio (OR) of reporting overall care as “Excellent” or “Very Good” (OR 1.33; 95% CI, 1.15-1.47). There was no difference between services in patients’ ability to identify their physician(s) (OR 0.89; 95% CI 0.61-1.11), in patients reporting a better understanding of the role of their physician(s) (OR 1.09; 95% CI, 0.94 – 1.23), or in their rating of overall coordination and teamwork (OR 0.71; 95% CI 0.42-1.89).

A subgroup analysis was performed on the 25% of hospitalist attendings in the general medicine teaching service, comparing this cohort to the hospitalist services, and found that patients perceived better overall care on the hospitalist service (OR 1.17; 95% CI 1.01 – 1.31) than on the general medicine service (Table 2). All other domains in subgroup analysis were not statistically significant. Finally, an ordinal logistic regression was performed for each of these outcomes, but did not show any major differences compared to the logistic regression of dichotomous outcomes.

Table 2.

3-Level, Mixed Effects Logistic Regression.

| Domains in Patient Experience* | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| “How would you rate your ability to identify the physicians and trainees on your general medicine team during the hospitalization?” | ||

| Model 1 | 0.89 (0.61-1.11) | 0.32 |

| Model 2 | 0.98 (0.67-1.22) | 0.86 |

| “How would you rate your understanding of the roles of the physicians and trainees on your general medicine team?” | ||

| Model 1 | 1.09 (0.94-1.23) | 0.25 |

| Model 2 | 1.19 (0.98-1.36) | 0.08 |

| “How would you rate the overall coordination and teamwork among the doctors and nurses who care for you during your hospital stay?” | ||

| Model 1 | 0.71 (0.42-1.89) | 0.18 |

| Model 2 | 0.82 (0.65-1.20) | 0.23 |

| “Overall, how would you rate the care you received at the hospital?” | ||

| Model 1 | 1.33 (1.15-1.47) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (1.01-1.31) | 0.04 |

Adjusted for age, gender, race, length of stay, Charlson Comorbidity Index, academic year, and prior hospitalizations within 1-year. General medicine teaching service is reference group for calculated OR.

Patient answers consisted of: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, or Poor. Model 1: General medicine teaching service compared to non-teaching hospitalist service; Model 2: Hospitalist attendings on general medicine teaching service compared to non-teaching hospitalist service.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to directly compare measures of patient experience on hospitalist and general medicine teaching services in a large, multi-year comparison across multiple domains. In adjusted analysis, we found that patients on non-teaching hospitalist services rated their overall care better than those on general medicine teaching services, while no differences in patients’ ability to identify their physician(s), understand their role in their care, or rating of coordination of care were found. Although the magnitude of the differences in rating of overall care may appear small, it remains noteworthy because of recent focus on patient experience at the reimbursement level, where small differences in performance can lead to large changes in payment. Because of the observational design of this study, it is important to consider mechanisms that could account for our findings.

The first are the structural differences between the two services. Our subgroup analysis comparing patients rating of overall care on a general medicine service with a hospitalist attending to a pure hospitalist cohort found a significant difference between the groups – indicating that the structural differences between the two groups may be a significant contributor to patient satisfaction ratings. Under the care of a hospitalist service, a patient would only interact with a single physician on a daily basis - possibly leading to a more meaningful relationship and improved communication between patient and provider. Alternatively, while on a general medicine teaching service, patients would likely interact with multiple physicians, as a result making their confidence in their ability to identify and perception at understanding physicians’ roles more challenging18. This dilemma is further compounded by duty hour restrictions, which have subsequently lead to increased fragmentation in housestaff scheduling. The patient experience on the general medicine teaching service may be further complicated by recent data that shows residents spend a minority of time in direct patient care19,20, which could additionally contribute to patient's inability to understand who their physicians are and to the decreased satisfaction with their care. This combination of structural complexity, duty hour reform, and reduced direct patient interaction would likely decrease the chance a patient will interact with the same resident on a consistent basis5,21, thus making the ability to truly understand who their caretaker is, and the role they play, more difficult.

Another contributing factor could be the use of NPAs on our hospitalist service. Given that these providers often see the patient on a more continual basis, hospitalized patients’ exposure to a single, continuous caretaker may be a factor in our findings.22 Furthermore, with studies showing that hospitalists also spend a small fraction of their day in direct patient care23–25, the use of NPAs may allow our hospitalists to spend greater amounts of time with their patient, thus improving patients’ rating of their overall care, and influencing their perceived ability to understand their physicians’ role.

While there was no difference between general medicine teaching and hospitalist services with respect to patient understanding of their roles, our data suggest that both groups would benefit from interventions to target this area. Focused attempts at improving patient's ability to identify and explain the roles of their inpatient physician(s) have been performed. For example, previous studies have attempted to improve a patient's ability to identify their physician through physician facecards8,9 or the use of other simple interventions (i.e. bedside whiteboards).4,26 Results from such interventions are mixed, as they have demonstrated the capacity to improve patient's ability to identify who their physician is, while few have shown any appreciable improvement in patient satisfaction.26

While our findings suggest that structural differences in team composition may be one possible explanation, it is also important to consider how the quality of care a patient receives affects their experience. For instance, hospitalists have been shown to produce moderate improvements in patient-centered outcomes such as 30-day readmission27 and hospital length of stay14,28–31 when compared to other care providers, which in-turn could be reflected in the patient's perception of their overall care. In a large national study of acute care hospitals using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey, Chen and colleagues found that for most measures of patient satisfaction, hospitals with greater use of hospitalist care were associated with better patient-centered care.13 These outcomes were in part driven by patient-centered domains; such as: discharge planning, pain control, and medication management. It is possible that patients are sensitive to the improved outcomes that are associated with hospitalist services, and reflect this in their measures of patient satisfaction.

Lastly, because this is an observational study and not a randomized trial, it is possible that the clinical differences in the patients cared for by these services could have led to our findings. While the clinical significance of the differences in patient demographics were small, patients seen on the hospitalist service were more likely to be older white males, with slightly longer LOS, with greater comorbidities, and more hospitalizations in the previous year than those seen on the general medicine teaching service. Additionally, our hospitalist service frequently cares for highly specific subpopulations (i.e. liver and renal transplant patients, and oncology patients), which could influence our results. For example, transplant patients who may be very grateful for their “second chance”, are preferentially admitted to the hospitalist service, which could have biased our results in favor of hospitalists32. Unfortunately, we were unable to control for all such factors.

While we hope that multivariable analysis can adjust for many of these differences, we are not able to account for possible unmeasured confounders such as time of day of admission, health literacy, personality differences, physician turnover, or nursing and other ancillary care that could contribute to these findings. In addition to its observational study design, our study has several other limitations. First, our study was performed at a single institution, thus limiting its generalizability. Second, as a retrospective study based on observational data, no definitive conclusions regarding causality can be made. Third, while our response rate was low, it is comparable to other studies that have examined underserved populations.33 Fourth, because our survey was performed 30-days after hospitalization, this may impart imprecision on our outcomes measures. Finally, we were not able to mitigate selection bias through imputation for missing data .

All together, given the small absolute differences between the groups in patients’ ratings of their overall care compared to large differences in possible confounders, these findings call for further exploration into the significance and possible mechanisms of these outcomes. Our study raises the potential possibility that the structural component of a care team may play a role in overall patient satisfaction. If this is the case, future studies of team structure could help inform how best to optimize this component for the patient experience. On the other hand, if process differences are to explain our findings, it is important to distill the types of processes hospitalists are using to improve the patient experience and potentially export this to resident services.

And finally, if similar results were found in other institutions, these findings could have implications on how hospitals respond to new payment models that are linked to patient experience measures. For example, the Hospital Value based purchasing program currently links Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services payments to a set of quality measures which consist of 1) clinical processes of care (70%) and 2) the patient experience (30%)1. Given this linkage, any small changes in the domain of patient satisfaction could have large payment implications on a national level.

CONCLUSION

In summary, in this large-scale, multi-year study, patients cared for by a non-teaching hospitalist service reported greater satisfaction with their overall care than patients cared for by a general medicine teaching service. This difference could be mediated by the structural differences between these two services. As hospitals seek to optimize patient experiences in an era where reimbursement models are now being linked to patient experience measures, future work should focus on further understanding the mechanisms for these findings.

Acknowledgments

Financial/Commercial Disclosures: Financial support for this work was provided by Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Program, (RWJF Grant ID 63910 Meltzer, Principal Investigator), a Midcareer Career Development Award from the National Institute of Aging (1 K24 AG031326-01, PI Meltzer), and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (NIH/NCATS 2UL1TR000430-08, Solway PI, Meltzer Core Leader).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interests to report.

References

- 1. [February 2, 2015]; CAHPS® Hospital Survey (HCAHPS®)Fact Sheet August 2013 - August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf.

- 2.Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364–370. doi: 10.1002/jhm.510. doi:10.1002/jhm.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [January 15, 2015]; Common Program Requirements - CPRs2013.pdf. http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf.

- 4.Maniaci MJ, Heckman MG, Dawson NL. Increasing a patient's ability to identify his or her attending physician using a patient room display. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1084–1085. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.158. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2010.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora V, Gangireddy S, Mehrotra A, Ginde R, Tormey M, Meltzer D. Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in-hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199–201. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.565. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O'Leary KJ, Kulkarni N, Landler MP, et al. Hospitalized patients’ understanding of their plan of care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):47–52. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0232. doi:10.4065/mcp.2009.0232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calkins DR, Davis RB, Reiley P, et al. Patient-physician communication at hospital discharge and patients’ understanding of the postdischarge treatment plan. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):1026–1030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arora VM, Schaninger C, D'Arcy M, et al. Improving inpatients’ identification of their doctors: use of FACE cards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf Jt Comm Resour. 2009;35(12):613–619. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(09)35086-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons Y, Caprio T, Furiasse N, Kriss M, Williams MV, O'Leary KJ. The impact of facecards on patients’ knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospital physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137–141. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2100. doi:10.1002/jhm.2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Connor AB, Lang VJ, Bordley DR. Restructuring an inpatient resident service to improve outcomes for residents, students, and patients. Acad Patient Experience on Hosp/Teach Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2011;86(12):1500–1507. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182359491. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182359491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O'Malley PG, Khandekar JD, Phillips RA. Residency training in the modern era: the pipe dream of less time to learn more, care better, and be more professional. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2561–2562. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.22.2561. doi:10.1001/archinte.165.22.2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidyarthi AR, Arora V, Schnipper JL, Wall SD, Wachter RM. Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign-out. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):257–266. doi: 10.1002/jhm.103. doi:10.1002/jhm.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen LM, Birkmeyer JD, Saint S, Jha AK. Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national Medicare population. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2013;8(3):126–131. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2001. doi:10.1002/jhm.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meltzer D, Manning WG, Morrison J, et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arora V, Dunphy C, Chang VY, Ahmad F, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer D. The Effects of On-Duty Napping on Intern Sleep Time and Fatigue. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):792–798. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00005. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-144-11-200606060-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cleary PD, Edgman-Levitan S, Roberts M, et al. Patients evaluate their hospital care: a national survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 1991;10(4):254–267. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.10.4.254. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.10.4.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [January 7, 2015];HCUPnet: A tool for identifying, tracking, and analyzing national hospital statistics. http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp?Id=F70FC59C286BADCB&Form=DispTab&JS=Y&Action=Accept.

- 19.Reilly BM. Don't Learn on Me — Are Teaching Hospitals Patient-Centered? N Engl J Med. 2014;371(4):293–295. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1405709. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1405709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Block L, Habicht R, Wu AW, et al. In the wake of the 2003 and 2011 duty hours regulations, how do internal medicine interns spend their time? J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1042–1047. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2376-6. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2376-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fletcher KE, Visotcky AM, Slagle JM, Tarima S, Weinger MB, Schapira MM. The composition of intern work while on call. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1432–1437. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2120-7. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2120-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desai SV, Feldman L, Brown L, et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation-compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2973. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turner J, Hansen L, Hinami K, et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2754-0. doi:10.1007/s11606-013-2754-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim CS, Lovejoy W, Paulsen M, Chang R, Flanders SA. Hospitalist time usage and cyclicality: opportunities to improve efficiency. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):329–334. doi: 10.1002/jhm.613. doi:10.1002/jhm.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tipping MD, Forth VE, O'Leary KJ, et al. Where did the day go?--a time-motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):323–328. doi: 10.1002/jhm.790. doi:10.1002/jhm.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Baker DW. How hospitalists spend their time: insights on efficiency and safety. J Hosp Med Off Publ Soc Hosp Med. 2006;1(2):88–93. doi: 10.1002/jhm.88. doi:10.1002/jhm.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Francis JJ, Pankratz VS, Huddleston JM. Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physician's photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(6):604–608. doi: 10.4065/76.6.604. doi:10.4065/76.6.604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chin DL, Wilson MH, Bang H, Romano PS. Comparing patient outcomes of academician-preceptors, hospitalist-preceptors, and hospitalists on internal medicine services in an academic medical center. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1672–1678. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2982-y. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2982-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rifkin WD, Conner D, Silver A, Eichorn A. Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community-based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(10):1053–1058. doi: 10.4065/77.10.1053. doi:10.4065/77.10.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Kenwood C, Benjamin EM, Auerbach AD. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2589–2600. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa067735. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa067735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Peterson MC. A Systematic Review of Outcomes and Quality Measures in Adult Patients Cared for by Hospitalists vs Nonhospitalists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):248–254. doi: 10.4065/84.3.248. doi:10.4065/84.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.White HL, Glazier RH. Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):58. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-58. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-9-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomsen D, Jensen BØ. Patients' experiences of everyday life after lung transplantation. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(24):3472–3479. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02828.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.02828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ablah E, Molgaard CA, Jones TL, et al. Optimal Design Features for Surveying Low-Income Populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):677–690. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]