Abstract

American Indians/Alaska Natives (AI/AN) exhibit high levels of alcohol and drug (AOD) use and problems. Although approximately 70% of AI/ANs reside in urban areas, few culturally relevant AOD use programs targeting urban AI/AN youth exist. Furthermore, federally-funded studies focused on the integration of evidence-based treatments with AI/AN traditional practices are limited. The current study addresses a critical gap in the delivery of culturally appropriate AOD use programs for urban AI/AN youth, and outlines the development of a culturally tailored AOD program for urban AI/AN youth called Motivational Interviewing and Culture for Urban Native American Youth (MICUNAY). We conducted focus groups among urban AI/AN youth, providers, parents, and elders in two urban communities in northern and southern California aimed at 1) identifying challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth and 2) obtaining feedback on MICUNAY program content. Qualitative data were analyzed using Dedoose, a team-based qualitative and mixed methods analysis software platform. Findings highlight various challenges, including community stressors (e.g., gangs, violence), shortage of resources, cultural identity issues, and a high prevalence of AOD use within these urban communities. Regarding MICUNAY, urban AI/AN youth liked the collaborative nature of the motivational interviewing (MI) approach, especially with regard to eliciting their opinions and expressing their thoughts. Based on feedback from the youth, three AI/AN traditional practices (beading, AI/AN cooking, and prayer/sage ceremony) were chosen for the workshops. MICUNAY is the first AOD use prevention intervention program for urban AI/AN youth that integrates evidence-based treatment with traditional practices. This program addresses an important gap in services for this underserved population.

Keywords: Native American youth, traditional practices, motivational interviewing, alcohol and drug use, culture, qualitative analysis, intervention development

1. INTRODUCTION

There is a need for culturally-appropriate alcohol and drug (AOD) prevention and intervention programs for urban American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth. In 2013, AI/ANs aged 12 or older had the 2nd highest rate of current illicit drug use compared to any other single ethnic/racial group in the U.S., and among youth aged 12 to 17 in 2013, AI/ANs had the 2nd highest rates of heavy drinking in the U.S. (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014). Also, data from school-based surveys in California from 1997 to 2006 showed that for nearly all substances surveyed—alcohol, marijuana, heroin, inhalants, amphetamines, and cocaine—rates of use were consistently higher among AI/AN youth in all age groups (seventh, ninth, and eleventh grades) compared to all other racial/ethnic groups (Wright, Nebelkopf, & Jim, 2007).

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, approximately 70% of AI/ANs reside within an urban setting (Norris, Vines, & Hoeffel, 2012). Studies to date conducted among urban AI/ANs have demonstrated concerning AOD use trends. For example, Dickerson and colleagues found that at-risk AI/ANs adults (individuals at risk for HIV/AIDS and AOD use attending programs providing prevention and counseling services) in an urban setting reported an earlier onset of alcohol, marijuana, methamphetamine, and other drug use compared to all other at-risk ethnic/racial groups within Los Angeles County (Dickerson, Fisher, et al., 2012). Furthermore, in a large trial comprised of a diverse group of middle school youth age 12–15 in 16 schools across three urban school districts (N = 9,528), AI/AN youth reported higher lifetime alcohol use and stronger intentions to use alcohol and marijuana compared to youth in all other racial/ethnic groups (D'Amico, Tucker, et al., 2012). Despite these high rates of AOD use among urban AI/AN youth, very few evidence-based, culturally-appropriate programs exist for this population.

AI/ANs residing in urban areas in the U.S have a unique history. Briefly, the Indian Relocation Act of 1956 financed the relocation of AIs residing on reservations to urban centers, providing them funding to establish job training centers (James, 1992). However, this move had many detrimental effects on this population including numerous psychosocial problems (Evans-Campbell, Lindhorst, Huang, & Walters, 2006; LaFromboise, Berman, & Sohi, 1994). For example, many AI/ANs who moved to urban areas found themselves homeless, unemployed, in poverty, without a strong cultural base or community and unable to achieve economic stability. In addition, the relocation of AI/ANs to urban areas appears to have had persisting or “intergenerational effects.” Poverty rates among AI/ANs in Denver, Phoenix, and Tucson are currently nearly 30%, and approximately 25% of AI/ANs live in poverty in Chicago, Oklahoma City, Houston, and New York (Williams, 2013) compared to 19.1% among the general U.S. population who live in these cities (DeNavas-Walt & Proctor, 2014). Furthermore, as a result of acculturative stress directly and indirectly associated with historical related trauma, AI/ANs typically experience poorer mental health outcomes (Duran & Duran, 1995) and higher rates of AOD use compared to other races/ethnicities (Lane & Simmons, 2011; Myhra, 2011; Whitesell, Beals, Crow, Mitchell, & Novins, 2012).

Unique risk factors may predispose urban AI/ANs to initiate AOD use during adolescence. For instance, a diminished sense of a visible AI/AN community in large urban centers may contribute to few opportunities to engage in AI/AN traditional healing practices that have historically emphasized notions of health and well-being (Dickerson & Johnson, 2012; Native American Health Center, 2012). Thus, it may be especially challenging for urban AI/AN youth to gain a sense of belonging and cultural identity within the urban environment. This could be detrimental as connection with cultural identity can positively affect an AI/AN adolescent’s self-esteem and self-construct during this time of development (Smokowski, Evans, Cotter, & Webber, 2014; Stumblingbear-Riddle & Romans, 2012). In a recent study with urban AI/AN youth, Stumblingbear-Riddle and Romans (2012) found that stronger enculturation and more social support from friends among urban AI/AN adolescents were both associated with higher resilience, which is often associated with less AOD use (Weiland, et al., 2012; Wingo, Ressler, & Bradley, 2014). Given that AI/AN youth often exhibit crucial differences in their ways of viewing the world compared to other racial/ethnic groups of youth (Brown, 2010; Brown, Hruschka, & Worthman, 2009), it is important to understand their conceptualization of addiction and desistance from AOD use and the related stressors, barriers and cultural differences that may exist in order to build successful AOD use prevention programs for these youth.

Many studies and qualitative-based community based gatherings have emphasized the importance that the AI/AN community places on integrating evidence based treatments with AI/AN traditional practices in AOD use programs for AI/AN youth (Dickerson, Johnson, Castro, Naswood, & Leon, 2012; Native American Health Center, 2012). Using focus groups and interviews with AI/AN youth, parents, and providers, Dickerson and colleagues (2012) demonstrated the need for culturally-appropriate interventions for AI/AN youth; namely, that there was a lack of programs integrating AI/AN traditional activities with evidenced based treatments, which was cited as a significant barrier to seeking care within Los Angeles County. Dickerson et al. (2012) also found that a large number of urban AI/AN youth are lacking AI/AN traditional activity opportunities and may not have ways to connect to an AI/AN identity in an urban environment (Dickerson, Johnson, et al., 2012). Examples of AI/AN traditional practices include a wide spectrum of activities ranging from learning to make jewelry, drumming, talking circles, sweat lodge ceremonies, to 7-day Navajo traditional ceremonies.

In addition to utilizing traditional healing practices, many clinicians serving AI/ANs emphasize the usefulness of Motivational Interviewing (MI) (Dickerson, Moore, Rieckmann, Croy, & Novins, 2015; Tomlin, Walker, Grover, Arquette, & Stewart, 2014; Venner, Feldstein, & Tafoya, 2007). MI is one of the most widely-used evidence-based treatments (EBTs) for AOD use in the U.S (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP), 2014). It is a client-centered therapeutic modality to help clients explore and resolve ambivalence and helps to elicit the client's own motivations for change (Miller & Rollnick, 2012; Rollnick, Miller, & Butler, 2008). Studies have found that the non-judgmental, empathic, and collaborative approach of MI works well with diverse groups of adolescents (Baer, Garrett, Beadnell, Wells, & Peterson, 2007; D'Amico, et al., 2015; D'Amico, Miles, Stern, & Meredith, 2008; Feldstein Ewing, Walters, & Baer, 2012) and can be especially helpful for youth who may be from a disadvantaged/marginalized background or a cultural minority (Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005). Among AI/AN adults, Venner and colleagues (2007) and Tomlin and colleagues found that MI closely mirrored AI/AN traditions and was culturally appropriate for AI/ANs. They worked in partnership with Native American adult clients across several tribes to develop their manuals (Tomlin, et al., 2014; Venner, et al., 2007). In addition, a 2011 study by Gilder and colleagues examined acceptability of MI with Native American youth on contiguous rural southwest California reservations by conducting surveys with 36 Native American tribal leaders and members. Overall, tribal leader and member participants reported that an MI research program to reduce underage drinking would be well regarded in this reservation community (Gilder, et al., 2011). Given the importance of focusing on AI/AN traditional practices and the potential acceptability of MI among the Native American community, integrating these two components could lead to an innovative, developmentally and culturally relevant program for urban AI/AN youth that may increase well-being and spirituality, provide a stronger sense of cultural identity, and decrease AOD use. We therefore worked with two large urban AI/AN communities in northern and southern California to address this gap and develop a new program integrating traditional practices and MI to target AOD use among urban AI/AN youth.

1.1. MICUNAY

MICUNAY (Motivational Interviewing and Culture for Native American Youth) is an AOD use prevention intervention program that integrates MI and AI/AN traditional practices. The original foundation of the program is based on extensive community-based work conducted by Daniel Dickerson and Carrie Johnson (Dickerson, Johnson, et al., 2012; Dickerson & Johnson, 2011; Dickerson & Johnson, 2012; Dickerson, et al., 2014), Kurt Schweigman (Native American Health Center, 2012), Ryan Brown (Brown, 2010; Brown, Copeland, Costello, Angold, & Worthman, 2009; Brown, Hruschka, et al., 2009), and Elizabeth D’Amico (D'Amico, Green, et al., 2012; D'Amico, Hunter, Miles, Ewing, & Osilla, 2013; D'Amico, et al., 2008; D'Amico, Osilla, & Hunter, 2010). MICUNAY targets a variety of behaviors including reducing AOD use and increasing well-being, spirituality and cultural identification. All MICUNAY workshops use a MI approach and different MI strategies, such as discussion of the pros and cons of AOD use and rulers (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). MICUNAY also utilizes the Northern Plains Medicine Wheel, which is a conceptual, culturally-acceptable model (Dapice, 2006) routinely utilized and accepted in health clinics serving urban AI/ANs in California. The Northern Plains Medicine Wheel focuses on emotional, mental, physical, and spiritual aspects of well-being and helps to provide participants with a visual representation of session content.

To our knowledge, there are no interventions for urban AI/AN youth that utilize AI/AN traditional practices and MI to address AOD among AI/AN youth. This paper describes the development of MICUNAY and of the MICUNAY logo based on focus groups with urban AI/AN youth, parents, providers and community stakeholders as well as extensive collaboration with experts in AI/AN psychosocial issues and interventions.

2. METHODS

2.1 Sample and recruitment

We utilized a community-based participatory approach in our development of the MICUNAY program (Fisher & Ball, 2003; Larson, Schlundt, Patel, Goldzweig, & Hargreaves, 2009; Minkler & Wallerstein, 2003). The study team is well known for their community based work. Dickerson is an Alaska Native (Inupiaq) addiction psychiatrist and substance abuse researcher who has worked with AI/AN communities for many years, Brown has done extensive work with the Cherokee Nation, and D’Amico has worked with numerous community settings to develop interventions for diverse groups of adolescents with community input. Further, Dr. Carrie Johnson (Wahpeton Dakota) and Kurt Schweigman, M.P.H. (Oglala Lakota) are well-recognized substance abuse and mental health experts for the AI/AN community. The design involved direct collaboration with two large urban communities in northern and southern California. Specifically, we sought input from AI/AN youth, parents of AI/AN youth, providers specializing in services to the AI/AN community and two Community Advisory Boards (CAB) comprised of AI/AN elders and senior stakeholders. We conducted ten focus groups (FGs) in all, each of which consisted of between 3 and 12 participants: 4 youth FGs, 2 parent FGs, 2 provider FGs, and 2 CAB FGs. Parent groups were mostly female, whereas other groups were roughly evenly balanced by gender. Youth were age 14–18, and tribal affiliation was varied and reflected the heterogeneity of tribal representation in the two large urban areas. We do not provide data with regard to tribal affiliation of youth in order to protect tribal confidentiality.

Focus groups were conducted in two large urban communities in northern and southern California (equal number of groups in each location) and near locations providing services to the AI/AN community. Respondents were recruited through fliers posted at service provider locations and through the personal and professional networks of the authors and their colleagues. Participants were given a $50 gift card in return for their attendance at the two-hour FG.

2.2 Procedures and data collection for development of final MICUNAY program

All recruitment, data collection, and analytic procedures were approved by RAND’s Institutional Review Board. The purpose of the focus groups was to collect feedback in order to complete the development of MICUNAY and to gather information with regard to challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth. Focus groups followed a semi-structured format whereby feedback was obtained specifically on 1) challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth (community stressors, cultural identity and AOD use within their urban communities) and 2) MICUNAY content (MI components, traditional practice components, and MICUNAY logo). Challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth were discussed in order to gain a better understanding of relevant issues among urban AI/AN youth that would subsequently help in the delivery of MICUNAY program. Sessions began with an icebreaker, and the most sensitive and difficult topics (e.g., struggles faced by youth, AOD use in the community) were placed in the middle of sessions, bordered by less emotional topics at the beginning and end of FG sessions. Groups lasted between 45 and 120 minutes, with an average of roughly 90 minutes per group.

Focus groups included several freelisting activities (Bernard, 2013), in which respondents were asked to, for example, list preferred or favorite traditional practices or list substances used in the AI/AN community. Responses to freelisting exercises were written on large surfaces (whiteboards or paper easels) to provide talking points for the group. This output was photographed at the end of the FG session and used in the production of FG notes.

The three lead authors conducted all FGs, and were accompanied by trained note-takers. Note-takers recorded all FG sessions with the Livescribe™ Smartpen, which allows written notes on specified themes to be directly linked with relevant portions of audio. This blended format of notes with audio recordings allows for the rapid production of detailed “debrief notes” from interviews, in which the impressions of session leaders and note-takers can be blended with verbatim quotations to produce detailed content regarding specific, pre-identified domains of interest. In this case, these domains were: 1) challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth domain: community stressors, cultural identity, and AOD use within the urban community, and 2) MICUNAY content domain: MI components, traditional practice components, and MICUNAY logo. This summarizing procedure also allows FGs to take a natural conversational course, with topics mentioned and discussed at several points throughout the conversation and then collapsed at a later point for analytic purposes.

This process of creating debrief notes represents an early stage of analysis and synthesis of the content from FG sessions. It also helps combine relevant content and discussions from across the entire FG session into a single, clear, organized write-up. Moreover, debrief note write-ups allow for targeted extraction of content to serve a particular analytic purpose; in this case, the production of a culturally relevant MI prevention intervention program for urban AI/AN youth that specifically blended traditional practices with the use of MI to discuss AOD use and making healthy choices.

2.3 Procedures for MICUNAY logo development

A local AI artist, Robert Young, designed the logo for the MICUNAY program. He first met with the first and last authors of this paper and was provided an overview of the program. He then created five designs for review and consideration which were then presented to all of the FGs for feedback. Participants confidentially chose their favorite design. The design that garnered the most votes across all the groups became the MICUNAY logo.

2.4 Data analysis

We transcribed all focus group sessions to supplement initial analysis based on debrief notes. Debrief notes and transcripts were entered into the team-based qualitative and mixed methods analysis software platform, Dedoose. Dedoose allows for simultaneous coding by multiple coders, as well as viewing and oversight of the coding process by third parties, simply by logging into a shared analytic platform (SocioCultural Research Consultants, 2014). It also allows for flexible, team-based construction of coding hierarchies and code definitions. Coding progress and excerpts can be easily visualized and shared with all team members during the coding process, which eases collaboration and management. These capabilities were particularly useful as team members were geographically dispersed.

Thematic content was coded using a mixture of inductive, exploratory coding with deductive coding of FG content according to pre-identified domains of interest (Bernard & Ryan, 2010). As noted above, coding was focused on two primary pre-identified areas: (1) challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth (including Community Stressors, Cultural Identity, and AOD use within the urban community), and (2) MICUNAY Content (MI components, traditional practice components, and MICUNAY logo). These areas were chosen in targeted fashion for their relevance to the construction of a culturally appropriate AOD prevention intervention program for this population.

All thematic coding was conducted by the two lead authors. After creating brief definitions of the two broad topical areas, coders read through all transcripts debrief notes, including both summaries and direct quotations from the FG sessions. The coders then tagged all relevant content and began to create exploratory categories to organize excerpts of text into meaningful categories or ‘codes.’ Over several meetings, the two coders agreed upon a final set of themes to characterize the content covered in focus groups within the two broad categories and five subcategories described above. To make sure the MICUNAY program was properly attuned to urban AI/AN culture and community context, all authors read through the coded thematic content regarding challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth (community stressors, cultural identity, and AOD use within the urban community). In addition, all of the traditional practices mentioned by youth were entered into an Excel table in order to quantify frequency of mention for individual activities. To select the final list of traditional practices to be integrated with the MI component of MICUNAY, we considered frequency of mention, along with the amount of time the activity was discussed, and logistical feasibility. Final decisions on traditional practices also factored in subjective impressions of youth excitement and enthusiasm regarding specific activities discussed during the focus groups.

2.5 Final development of MICUNAY program

Feedback on challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth helped us gain an understanding of what topics might be relevant for the MICUNAY workshops. We also obtained additional feedback from all focus groups on specific MICUNAY MI components and on the MICUNAY traditional practice components. For the MI components, we discussed what MI strategies might be helpful for youth (e.g., rulers, pros/cons) and we showed FGs the handouts focused on these strategies from D’Amico’s previous MI projects (D'Amico & Edelen, 2007; D'Amico, et al., 2015; D'Amico, et al., 2010; D'Amico, Tucker, et al., 2012) to determine cultural appropriateness of the strategies and to obtain suggestions for modifying handouts for urban AI/AN youth. For the cultural components, we only asked youth to freelist traditional practices that they would like to participate in and to further discuss which activities might be most interesting. Information obtained from these questions assisted our research team with data that were later used for finalizing the content of the 3 MICUNAY workshops and final manual development. We also gathered feedback on the cultural appropriateness of the MI components of MICUNAY and any need for cultural adaptations to the MICUNAY program. Furthermore, upon completion of focus group analyses, we focused on integrating the MI and traditional practices components in order to appropriately blend the MICUNAY program specifically for urban AI/AN youth.

3. RESULTS

3.1 Final MICUNAY logo

We presented five designs to FG participants prepared by the MICUNAY artist and one final logo was selected. The designs all incorporated different AI/AN themes, including a medicine wheel, animals, such as a bird and bear, and logos integrating an “urban feel.” The final logo that received the most votes across all groups integrated a medicine wheel with some urban cities; however, the youth suggested changes to this logo, specifically, they felt that this design could be improved if it had even more of an “urban feel” and better symbolized their respected cities. Also, the final color chosen was red. However, participants felt that different colors could be used interchangeably for flyers, posters, t-shirts, etc. These suggestions were provided to Mr. Young who then finalized the design, which was then presented back to the youth who gave approval for the final logo (See Figure 1). As with the MICUNAY program, the final logo also blended traditional and urban by showing the Medicine Wheel and incorporating urban landscapes, bridges, and an ocean scene.

Figure 1.

MICUNAY Logo

3.2 Overall challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth

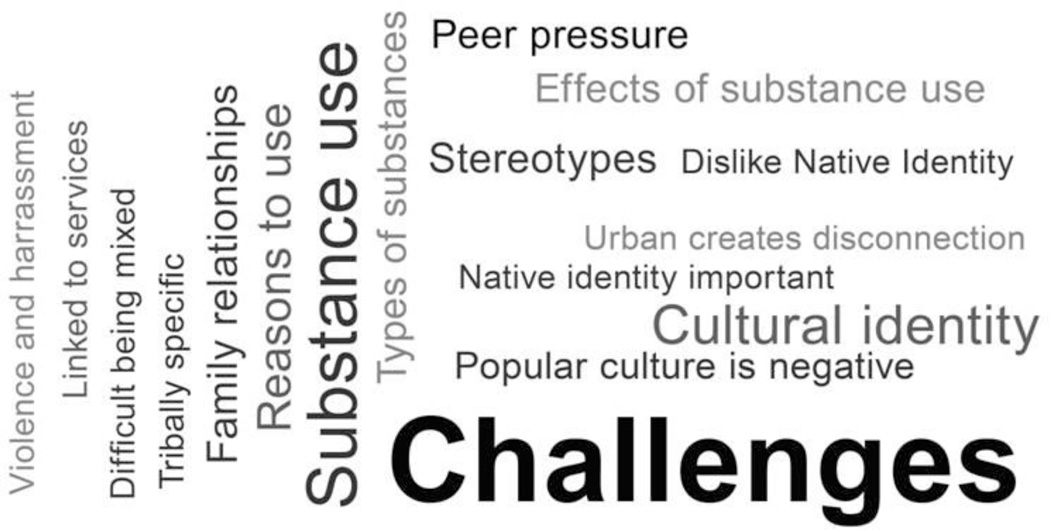

Figure 2 illustrates the prevalence of overall challenges that were identified by youth, with the size of the font indicating the relative prevalence of each thematic area. As the figure shows, struggles with urban AI/AN cultural identity and AOD use itself were mentioned most frequently by youth. Violence and harassment were also mentioned with respect to both cultural identity and its linkage to AOD use.

Figure 2.

Challenges Youth Identified During Focus Groups

3.2.2 Community stressors

All FGs reported various community stressors, including the presence of gangs, violence, harassment, financial difficulties and a shortage of resources (Table 1). Focus group participants also reported a wide prevalence of homicides and suicides within their community.

Table 1.

Community Stressors

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Safety/Violence |

|

| Lack of resources |

|

| Historical trauma effects |

|

| Peer pressure and stress |

|

Note: CAB = The MICUNAY Community Advisory Board. This is the board of Native elders and community leaders we established to provide input on Native youth AOD use and feedback on the MICUNAY program content.

3.2.3 Safety

Many youth reported not feeling safe in their neighborhoods or on public transportation due to the presence of gangs, violence, and harassment (Table 1). Youth felt “trapped” in their neighborhood and reported some of the effects of violence that they had experienced, such as homicides and suicides. For example, some youth reported attending multiple funerals as a result of their exposure to violence and gang activity in their communities. Youth in the FGs also reported feeling stress due to issues that many teenagers experience, including homework, stress from parents and elders as it relates to following rules and expectations, having a crush on someone, peer pressure, competition, and feeling judged by others. The CAB focus groups emphasized that urban AI/AN’s exposure to violence, unemployment, and poverty is often the result of historical trauma, including the effects of relocation and assimilation into the urban community. The CAB also felt that the effects of historical trauma on urban AI/ANs were “intergenerational,” with these effects carried onto successive generations.

3.2.4 Lack of resources

Parent focus group members stated that many parents struggle financially and feel stressed. Provider FGs indicated that there is a shortage of resources for urban AI/AN teens making it difficult for them to access a supportive network within their communities. In addition, provider FGs indicated that there is limited funding for culturally relevant programs for urban AI/AN youth.

3.3 Cultural identity issues experienced by urban AI/AN youth

All of the FGs reported cultural identity issues, including negative AI/AN stereotypes and improper or incomplete ethnic or cultural labeling by others. In addition to issues associated with AI/AN collective identity, FGs also expressed complexities associated with tribal diversity and representation. All FGs emphasized the challenges for youth to connect to their AI/AN culture due to a diminished exposure of their culture in their communities and homes, and AI/AN youth expressed a wide range of AI/AN cultural connectedness (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cultural Identity

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Not feeling connected to AI/AN culture |

|

| Having pride in AI/AN culture |

|

| Improper or incomplete ethnic or cultural labeling by others |

|

| Challenges with connecting with AI/AN culture in urban environment |

|

Note: CAB = The MICUNAY Community Advisory Board. This is the board of Native elders and community leaders we established to provide input on Native youth AOD use and feedback on the MICUNAY program content.

3.3.1 AI/AN stereotypes

For the youth and parent focus groups, one of the most common themes expressed was negative AI/AN stereotypes (Table 2). For example, urban AI/AN youth reported feeling disturbed by other non-AI/AN teens dressing up in Native American traditional regalia and seeing stereotypes of Native Americans on social media such as Facebook. Another frequent frustration mentioned by youth was improper or incomplete ethnic or cultural labeling by others. One urban AI/AN youth stated that AI/AN youth were often mistaken as being white, black, or Mexican. In particular, youth who characterized themselves as “mixed” (AI/AN plus other racial/ethnic roots) found that they were rarely correctly identified as Native American. One youth stated, “I don’t see other people by their race, but I don’t see why they treat me like that, and half the time they call me Mexican – I don’t know how to speak Spanish but I’m Mexican [shrugs].” One youth reported that you can feel proud of being AI/AN, but there are challenges with being AI/AN in the urban environment.

3.3.2 Complexities with tribal diversity

Youth also expressed issues associated with the wide diversity of AI/AN tribal representation within the urban setting and of being mixed race (Table 2). For example, one urban AI/AN youth stated, “It’s so multicultural in [undisclosed urban city] … and sometimes it makes it easier to find identity, but sometimes you find someone with the same ethnicity but trying to find the same Tribe is hard.” Youth also described feeling a tension between tribally-specific practices and community connections on the Reservation or other Tribal lands and the urban context. For example, one youth respondent said, “It’s different in the urban area. I came from a Rez out there, and everything is sort of in tune, and it’s understandable. Here there are just noises and stuff, and it’s not the same, and nothing feels the same.”

3.3.3 AI/AN cultural identification

Among urban AI/AN youth respondents, we found a range of AI/AN cultural identification (Table 2). Some youth explicitly disavowed or stated disconnection with the Native identity. One urban AI/AN urban youth stated, “Pow Wows are stupid.” Other youth expressed a deep and abiding connection, participating regularly in AI/AN ceremonies. Parent groups felt that because youth may not feel secure with their AI/AN identity, they may experience low self-esteem from not knowing who they are. One parent stated that urban AI/AN youth need guidance to learn “what they’re made of.” Parent, CAB, and provider FGs said that many youth are not connected with their culture due to their Native languages not being spoken in their home, their parents not prioritizing them learning about their culture in their homes and some parents not having knowledge in their culture. Parents also expressed feeling guilty that they could sometimes not answer their children’s questions regarding cultural practices and roots due to a lack of knowledge on their own part.

3.4 AOD use within the urban community

All FGs reported issues and challenges in their urban community due to AOD use (Table 3). A wide prevalence of substances was reported with alcohol and marijuana being recognized as the most widely used substances. In addition, FG participants expressed that urban AI/AN youth within their communities often used AOD in order to cope or self-medicate due to exposure to violence. Parents and providers also believed that youth experienced a great deal of peer pressure and that rap musicians and movie actors were negative influences on urban AI/AN youth as it relates to AOD use.

Table 3.

AOD Use within the Urban Community

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| High availability of drugs |

|

| Reasons to use |

|

3.4.1 Prevalence of AOD use

All FGs reported that AOD use is widely prevalent in the community. Youth reported that AI/ANs within the urban setting used a wide variety of substances (Table 3), including methamphetamine, cocaine, ecstasy, prescription pills (Vicodin, OxyContin), heroin, LSD, nitrous oxide, inhalants, and cough medicine. They most frequently mentioned alcohol and marijuana. Youth also described the extensive presence and easy availability of substances. One youth said, “There is dope on every corner, liquor stores on every corner, so you can get high whenever you want.” Provider FGs also said that many youth may find drugs in medicine cabinets in their homes.

Youth described the strong connection between AOD use and negative outcomes among youth, including violence and even death. Youth said that substances are often used as an escape to cope with the consequences of violence, death, and physical threat or harassment. One youth respondent explicitly made these connections during a FG session: “I met a lot of people who have been through a lot of stuff, and at school they’re messed up, coked up and drunk…. I just had a friend pass away from it last week, and you definitely don’t want friends to do stuff like that, but they think they need it to feel better or not to think about anything and feel nothing.”

3.4.2 Reasons to use

The parent FGs indicated that youth experience a lot of peer pressure and that there is a “lack of community” support for their youth, which could help decrease their chances of using AOD. Some providers and parents said that urban AI/AN youth may self-medicate their trauma and exposure to violence with AOD use. This was also reflected in youth focus groups where one youth reported that some youth may use substances to get away from reality and family related problems. One CAB member also felt that substance use is “just part of growing up” and that it is routine for high school-age youth to use substances.

3.5 MICUNAY content

3.5.1 MICUNAY motivational interviewing component

Youth, parent, provider, and CAB focus groups were all provided with materials and information from previous intervention work conducted by this group and asked for their input (See Table 4). This consisted of showing FGs different handouts and having: (1) discussion of how to talk to youth about the effects of alcohol and drugs on the brain; (2) discussion of a “pathway to choices” illustrating how people make choices to get on or off a path that goes from “no AOD use” to “addiction”; and (3) discussion of statistics regarding US adolescent AOD use rates. Overall, participants from all focus groups viewed interacting with youth and having open discussion as a beneficial way to implement the program. Urban AI/AN youth liked the collaborative nature of the MI approach, especially with regard to eliciting their opinions and expressing their thoughts. The youth also overwhelmingly felt that the group should be interactive and not be like a lecture, and that the facilitator should get teens’ input on what was relevant in their communities by asking them questions about what was what happening around them and how they dealt with it. Also, focus group participants thought the handouts presented were helpful, and they suggested adaptations as it relates to cultural relevancy and the urban setting to enhance the benefits for this population.

Table 4.

MICUNAY Content – Motivational Interviewing Component

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Integrate MI therapy with cultural activities |

|

| “Nativize” the MI content |

|

| “Urbanize” MI materials |

|

| Make content more vivid/graphic |

|

Note: CAB = The MICUNAY Community Advisory Board. This is the board of Native elders and community leaders we established to provide input on Native youth AOD use and feedback on the MICUNAY program content.

Core elements of MI were viewed as having the potential to be beneficial for urban AI/AN youth as it relates to AOD use. For example, urban AI/AN youth liked the open and collaborative nature of MI and said that this approach helped them feel more connected with each other. For example, one urban AI/AN youth recommended, “…kind of make it [the program] like their own-kind of share their thoughts about different things…so you feel kind of connected.” Also, one parent stated, “I think it’s a much more open invitation for people to participate as opposed to like telling them what to do… so like more of an open discussion about cultural identity, about struggles, objectives…again, like putting it back on the kids and allowing them to feel open enough to feel that they’re in control.” Focus groups also felt that it was important to talk about the choices that youth have to make as urban AI/AN youth regarding AOD use. One CAB member stated the importance of this culturally by expressing, “So if you could share with them that “This is the Black Road [the bad way, the road of misfortune] and these are some things that are going to happen if you walk down this road. But then here’s the Red Road-these are the traditional way of living traditional way of thinking, and when you follow this road, these are the things that are going to happen…So that Red Road is a concept of our culture and our way of life, so maybe sharing that, teaching with them.” Focus group participants noted that it was especially relevant to talk about making good choices among urban AI/AN youth due to challenges that they may experience within their communities.

Regarding the handouts, participants believed that the “pathway of choices” handout was a good launching pad as it helped focus the discussion on the important issue of making healthy choices. However, participants recommended that the handout be more culturally relevant and more in-tune with their everyday lives in the urban setting. For example, one CAB member stated, “(among) Native people, symbolism and what we see is everything to us, spiritually, so to make this culturally appropriate is probably the first thing that you guys needs to do.” Another CAB participant stated, “make it be relevant to the environment they’re in.” Participants made several recommendations for “urbanizing” the handouts; one CAB participant stated, “maybe you could use like a city background.” Youth also viewed the handouts positively and provided specific suggestions for improvement in by inserting more urban content into handouts and making content more vivid, graphic and immediately relevant to youths’ lives (Table 4). This was part of a general push from groups to make the materials as vivid and engaging as possible for this population utilizing culturally-appropriate, earth-tone colors and AI/AN graphics and imagery

Focus group participants also liked the handouts with regard to brain development and they thought that learning the effects of AOD use on the brain was important. Education about brain development was viewed as a culturally relevant topic for urban AI/AN youth. For example, one CAB participant stated, “I was thinking of spirituality as part of the brain, which kind of connects with the traditional beliefs…and I’m just thinking too…because at this core age, their brain is still developing.”

3.5.2 MICUNAY Traditional Practice Component

Analysis of transcripts from all focus groups revealed four major thematic areas that focus groups discussed with respect to traditional practices: (1) accommodating tribal differences; (2) personalizing traditional practices; (3) gender differences; and (4) positive impact of traditional practices (see Table 5). Although some tribally specific practices were mentioned and suggested by youth, both youth and other groups expressed a willingness to overlook or blend these differences into more of a “Pan-Native American” approach that draws upon strengths from different tribal practices and traditions. Meanwhile, several groups discussed the need for youth to participate in traditional practices where they may have the opportunity to create items that they can keep and take home. This was suggested in order to help them connect with their own AI/AN cultural identity. Some concern was indicated with regard to gender taboos and gender roles around drumming; however, groups generally agreed that any gender differences in expectations for traditional practices could be overcome. Finally, all of the groups expressed ways that participation in AI/AN traditional practices could have a positive therapeutic effect on AI/AN urban youth by increasing self-esteem and a sense of rootedness to their AI/AN cultural identity.

Table 5.

MICUNAY Content – Traditional Practice Component

| Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|

| Accommodating tribal differences |

|

| Personalizing activities |

|

| Gender differences |

|

| Positive impact of traditional practices |

|

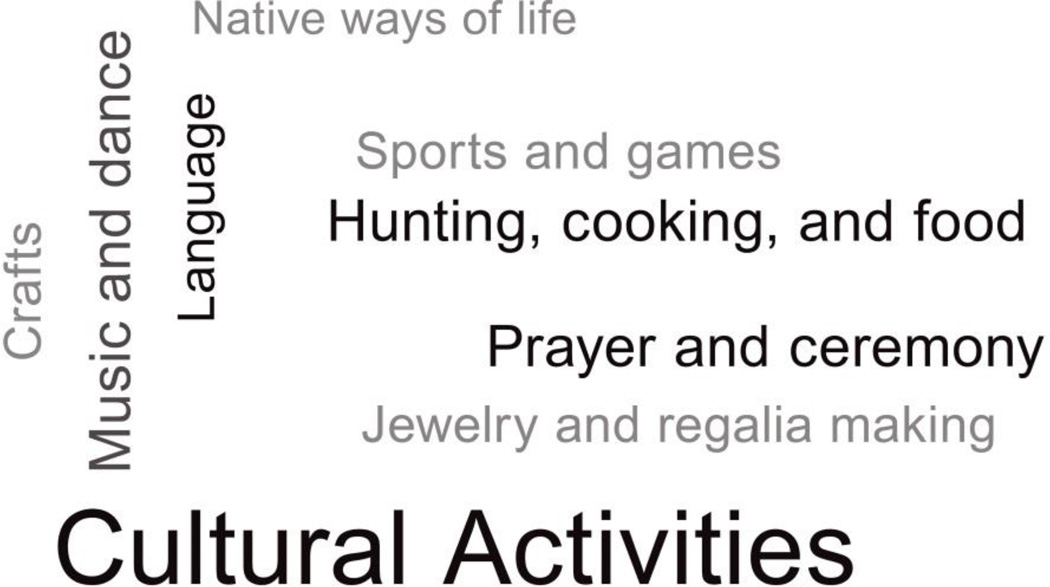

Overall, youth expressed enthusiasm for traditional practices – whether they had intimate knowledge and had already participated in such activities or had relatively little working knowledge or experience (See Table 5). Only one youth respondent expressed a lack of a desire to engage in any such activities. Except for youth who had spent time outside of the urban environment, i.e., on AI reservations, most youth indicated that their prior exposure to traditional practices had been through explicit community programs designed to educate youth about AI/AN practices. The AI/AN traditional practices that urban AI/AN youth were most interested in learning about and participating in are shown in Figure 3. The following AI/AN traditional practices were mentioned by at least 3 out of 4 youth focus groups – (a) beading, (b) pow-wows/drumming/music; (c) making clothing/regalia; (d) food (including learning to cook Native foods)/hunting and fishing; (e) learning about AI/AN ways of life (especially the practices of warriors); (f) learning Native language; and (g) prayer/ceremonies/blessing.

Figure 3.

Traditional Practices Youth Identified During Focus Groups

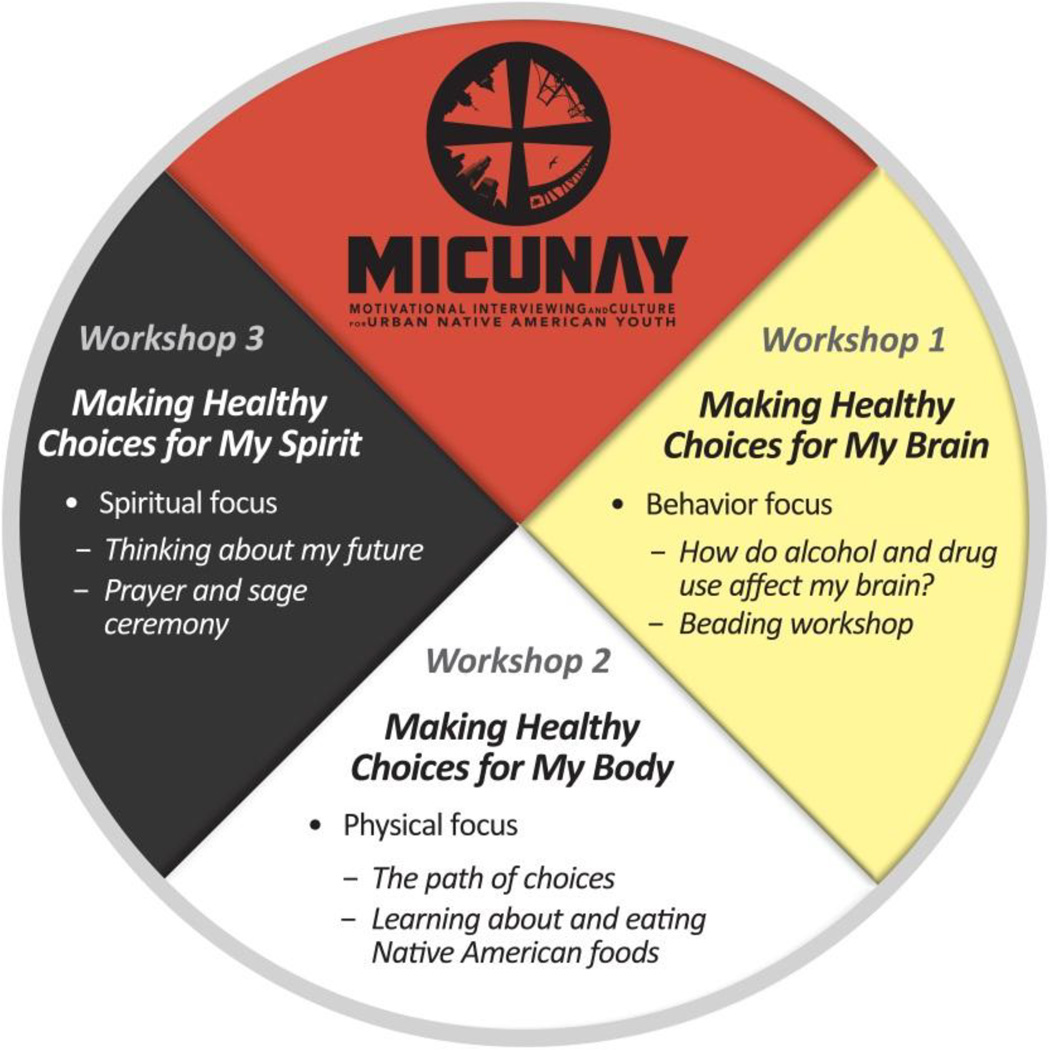

3.6 Integration of motivational interviewing discussions and traditional practices

One of the unique elements of successfully developing MICUNAY was to ensure that the MI component and traditional practice component seamlessly connected in order to ensure cohesiveness, deliverability and cultural relevance. This emphasis and priority was reflected within the focus groups as well. First, focus group participants liked the preliminary MICUNAY program outlined within the Medicine Wheel and how it integrated the MI component content and cultural activity content for each of the three workshops within the Medicine Wheel. Focus group participants believed that the Medicine Wheel was an important construct that urban AI/AN youth could use for their overall well-being and health. For example, one CAB participant stated, “when you explain that Medicine Wheel, and then it breaks it up into the quadrants: your spiritual, physical, mental, and emotional, those are all connected and when you’re out of balance in one, all the rest are out of balance too.”

Among all of the focus groups, especially the provider and CAB groups, many opportunities for blending or “pairing” traditional practices with the MI discussions were identified. One CAB participant stated, “and then having that activity sort of fit in. If we do the roads, then maybe the cultural activity then is the storytelling, so it kind of all fits, so then maybe it doesn’t feel rushed too.” One CAB participant stated, “and something with prayer, because prayer is strong and giving them those, not only in the activity of learning something but something that they could take back with them to teach them how to do those self-coping skills through your own traditional stuff.” As a result of this feedback, we have emphasized core components of AI/AN spirituality, emphasis on traditional notions of well-being and overall health throughout our MICUNAY manual for each of the final three MICUNAY workshops.

We also emphasized the importance of beginning MICUNAY sessions with a prayer and then discussing the community’s uses of prayer and other aspects of spirituality typically used within communities. Integrating spirituality throughout the MICUNAY intervention was accomplished in a variety of ways. During workshop one, we emphasize how brain development is an AI/AN concept and discuss how spiritual health is a critical component of MI-related brain development. Also, we discuss the spiritual connection of cooking and bead making and making healthy choices. We also discuss with youth that AOD use was never an AI/AN tradition or part of the lives of AI/ANs before contact with non-Native peoples.

Focus group participants also felt it was important to utilize talking circles for MICUNAY workshops to ensure that all content is provided in a culturally appropriate manner and to emphasize the sense of community and connectedness among urban AI/AN youth. This also helps to create a safe place for discussing potentially challenging topics. Thus, we utilize a talking circle format for all the workshops.

We integrated the concept of making healthy choices by utilizing elements of storytelling in the culturally adapted pathway of choices handout. In the MICUNAY pathway of choices handout, there is an opportunity for MICUNAY facilitators to teach about the Trickster, or coyote. We included the coyote within a city landscape with information on a potential path of AOD use and discuss making choices in a culturally appropriate manner. In each workshop for the cultural activity sessions, we discuss traditional AI/AN beliefs and how traditions focus on making healthy choices and staying in balance. We provide the example of the use of traditional tobacco as compared to the use of commercialized tobacco by teaching about the culturally-appropriate, ceremonial uses of tobacco as opposed to the recreational use of tobacco. In each of our MICUNAY workshops, we review aspects of the MICUNAY Medicine Wheel and highlight how the MI component naturally integrates with the traditional practice component. Thus, we were able to seamlessly blend the elements of MI within the traditional practices in the final development of the MICUNAY intervention manual.

3.7 Final MICUNAY Program

The final MICUNAY program comprises three two-hour workshops (Figure 4). We changed the format from six one-hour workshops to this shorter version due to transportation concerns raised in the FGs and to optimize feasibility. The three traditional practices selected (beading, cooking, and prayer/sage ceremony) were chosen based on youth suggestions and feasibility of providing these activities within the timeframe of the MICUNAY program. As noted earlier, an important part of the MICUNAY program was to integrate traditional practices with the MI discussions so that they blended together and “made sense” to the youth. For example, beading, which requires concentration and focus, was integrated with the MI discussion focused on “making healthy choices for my brain” for workshop 1. Thus, we emphasize the healthy benefits of beading on concentration and emotional and mental well-being and then discuss how AOD use might affect the brain and how to make healthy choices and avoid using AOD. Cooking was integrated with MI content focused on “making healthy decisions for my body” for workshop 2. This workshop emphasizes how youth must make choices regarding the path they choose to walk related to AOD use; that is whether they want to be on the path or if they want to get off the path; the workshop then focuses on health benefits of traditional AI/AN cooking. This workshop also teaches youth about AI/AN hunting practices, traditional gathering of fruits and vegetables, and AI/AN traditional medicines. A prayer and sage ceremony was integrated with the MI discussion focusing on “making healthy choices for my spirit” for workshop 3. This workshop emphasizes focusing on the future and how choices we make regarding AOD use can affect our spiritual well-being in the future; then discusses the healthy benefits of prayer and youth participate in a sage ceremony. Focus group participants felt the Medicine Wheel served as an important and culturally appropriate template from which to emphasize the four directions and four dimensions of wellness recognized in most AI/AN communities. The titles on our wheel: behavior, physical and spiritual were recommended by our focus groups and CABs (Figure 4). The behavior component of the wheel comprises the mental and emotional dimensions of well-being, which are typically included in most Medicine Wheels. Of note, all MICUANY workshops address aspects of the mental and emotional dimensions in both the MI components and the traditional practice components. For example, for the MI component in workshop one, youth are queried about how the choices they make may affect their mental and emotional well-being; in workshop two, they are asked how they can get positive feelings without using alcohol or drugs, and in workshop three they discuss how planning ahead may help them have better mental and emotional health in their future. In all workshops for the traditional practice component, they discuss all four dimensions of the wheel, the history of the medicine wheel, and how the dimensions are related and may affect the other dimensions. This approach ensures that all four dimensions (mental, emotional, physical and spiritual) are covered in the MICUNAY program.

Figure 4.

MICUNAY Medicine Wheel

Finally, we referred to the two MI Manuals culturally-adapted for AI/ANs (Tomlin, et al., 2014; Venner, et al., 2007) to ensure that we had addressed and incorporated topics relevant for this population. MI was perceived as an appropriate component of the MICUNAY program as it was in community-based works performed by both Tomlin and Venner. Other topics highlighted in these manuals included spirituality, the importance of community and cultural identity, and the role of AI/AN culture in overall health and wellness. These observations helped to ensure that MICUNAY is culturally appropriate and incorporates key elements of health and wellness for urban AI/AN youth.

4. DISCUSSION

The current study addresses a critical gap in the delivery of culturally appropriate AOD use prevention programs for urban AI/AN youth. Although numerous reports and studies have indicated the need for AOD use prevention intervention programs integrating both evidence based practices and traditional practices, to our knowledge, none exist that have undergone formal development and empirical testing for this population. Through our focus group work with AI/AN communities in two large urban communities in northern and southern California, we developed a formal curriculum for AI/AN youth that integrates both MI and traditional practices. Findings emphasize the importance of utilizing a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach. As a result of this approach, themes generated from these focus groups helped ensure that MICUNAY is culturally and developmentally relevant for this population.

Youth reported high enthusiasm for learning more about their culture. Previous reports have noted a shortage of opportunities to participate in traditional practices within the urban setting (Dickerson, Johnson, et al., 2012; Native American Health Center, 2012), and these youth also said that it’s difficult to engage in traditional practices within the urban setting. Results from our work highlight the need and potential benefits of providing urban AI/AN youth with an opportunity to engage in traditional practices and potentially strengthen their cultural identity, connect them to a supportive community, and learn about healthy behaviors which have been utilized and emphasized by tribes historically across the U.S.

Overall, we found that the urban AI/AN youth liked the discussion topics and handouts used in previous MI sessions with other teen populations (D'Amico, Green, et al., 2012; D'Amico, et al., 2010). They thought the brain handout and path of choices handout and discussion about the pros/cons of using helped them learn more about effects AOD use and choices that they could make to have a healthy future. For example, they thought that other urban AI/AN youth would like to learn how AOD use affects the brain because this isn’t information that is normally discussed with youth, and it provided a good opportunity to understand the effects, ask questions, and think about how this might affect their choices surrounding AOD use. They also provided important feedback on how to make these MI discussions more culturally relevant for them. For example, the path of choices focused on the pros and cons of AOD use and how to decide what path they wanted to take in their future. Due to feedback from the youth, the path metaphor involved discussions of the “trickster” or coyote, who is often seen in traditional AI/AN stories. Discussion of the path also focused on traditional use of tobacco versus recreational use. In sum, youth felt that the use of MI and discussion of these different topics provided a safe space for them to talk about AOD use and ask questions, to be heard by others and have their cultural and urban environments be understood.

One important piece of our work in this area was to highlight tribal diversity among AI/AN tribal groups. To date, over 562 federally-recognized tribes exist with their own tribal histories, unique cultures and languages. Diversity issues are especially prominent within the urban environment where individuals from various tribal groups are known to exist. Based on feedback from these different groups, we designed an intervention that incorporates common activities and philosophies known to exist across tribal traditions, which will hopefully encourage AI/AN youth to learn more about their own tribal traditions.

Many provider and CAB members viewed the urban AI/AN youth’s struggles as a result of historical trauma due to relocation and forced assimilation. They also felt that there were limited opportunities for urban AI/AN youth to participate in traditional practices due to budget issues among AI/AN clinics, low socioeconomic status and transportation issues, a shortage of AI/AN cultural awareness, and loss of language among the parents of urban AI/AN youths. All groups were therefore extremely supportive of the MICUNAY program as it focused on both enhancing cultural identity among AI/AN youth and addressed AOD use in a collaborative and non-judgmental way. They also liked how these two components were integrated and not just separate “events” (e.g., focus on the brain and AOD use and beading and concentration).

It’s important to note a few limitations. First, feedback was only obtained from two large urban areas in California and does not necessary generalize to all urban AI/ANs in the U.S. Second, groups were recruited opportunistically rather than assembling a representative sample of AI/AN individuals in each area. Despite limitations, findings provide an important understanding of relevant issues confronting urban AI/AN youth that and how to develop an AOD program tailored to meeting the unique needs of this population.

In conclusion, findings illustrate how a culturally relevant AOD program targeting AI/AN urban youth can be developed with a community-based participatory approach. We identified many challenges confronting urban AI/AN youth, which helped to better understand their unique needs in order to optimize the development of MICUNAY. In addition, we gathered valuable feedback on how to best integrate the MI discussions and AI/AN traditional practices. As a result, MICUNAY is able to uniquely respond to the needs of this urban population. We are currently in the first year of our clinical trial testing the potential benefits of MICUNAY in two large urban communities in northern and southern California. Youth who have participated in MICUNAY have been excited about the opportunity to learn about their culture and to discuss AOD use in their community and how to make healthier choices. We hope that MICUNAY can help meet the unique needs of this population and ultimately decrease and prevent AOD use and increase cultural connectedness among urban AI/AN youth.

Highlights.

Urban American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) youth face many challenges

Urban AI/AN youth need culturally appropriate alcohol and drug use programs

We developed MICUNAY (Motivational Interviewing and Culture for Urban Native American Youth)

MICUNAY integrates evidence-based treatment with traditional healing

Response from the AI/AN community for MICUNAY is promising

Acknowledgements

The current study was funded by the National Institute of Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse (1R01AA022066; PIs D’Amico & Dickerson) with co-funding by the National Institute on Drug Abuse. We would like to thank the clinics that allowed us to conduct the focus groups and the participants in the groups who shared their thoughts and opinions with us. We would also like to thank Lisa Miyashiro and Yashodhara Rana for their help in taking notes during the groups and organizing the data.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Baer JS, Garrett SB, Beadnell B, Wells EA, Peterson PL. Brief motivational intervention with homeless adolescents: Evaluating effects on substance use and service utilization. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:582–586. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR. Social research methods: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard HR, Ryan GW. Analyzing qualitative data: Systematic approaches. Los Angeles, Calif: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA. Crystal methamphetamine use among American Indian and White youth in Appalachia: Social context, masculinity, and desistance. Addiction Research & Theory. 2010;18(3):250–269. doi: 10.3109/16066350902802319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Copeland WC, Costello EJ, Angold A, Worthman CM. Family and community influences on educational outcomes among Appalachian youth. Journal of Community Psychology. 2009;37(7):795–808. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown RA, Hruschka DJ, Worthman CM. Cultural models and fertility timing among Cherokee and white youth: Beyond the mode. American Anthropologist. 2009;111(4):420–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2009.01152.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Edelen M. Pilot test of Project CHOICE: A voluntary after school intervention for middle school youth. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21(4):592–598. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Green HDJ, Miles JV, Zhou AJ, Tucker JA, Shih RA. Voluntary after school alcohol and drug programs: If you build it right, they will come. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2012;22(3):571–582. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Houck JM, Hunter SB, Miles JNV, Osilla KC, Ewing BA. Group motivational interviewing for adolescents: Change talk and alcohol and marijuana outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(1):68–80. doi: 10.1037/a0038155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Hunter SB, Miles JNV, Ewing BA, Osilla KC. A randomized controlled trial of a group motivational interviewing intervention for adolescents with a first time alcohol or drug offense. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2013;45(5):400–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Miles JNV, Stern SA, Meredith LS. Brief motivational interviewing for teens at risk of substance use consequences: A randomized pilot study in a primary care clinic. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2008;35:53–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Osilla KC, Hunter SB. Developing a group motivational interviewing intervention for adolescents at-risk for developing an alcohol or drug use disorder. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2010;28:417–436. doi: 10.1080/07347324.2010.511076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Amico EJ, Tucker JS, Miles JNV, Zhou AJ, Shih RA, Green HDJ. Preventing alcohol use with a voluntary after school program for middle school students: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial of CHOICE. Prevention Science. 2012;13(4):415–425. doi: 10.1007/s11121-011-0269-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dapice AN. The medicine wheel. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2006;17:251–260. doi: 10.1177/1043659606288383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD. Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2014. U.S. Census Bureau, Current population reports: Income, poverty, and health insurance coverage in the United States:2013; pp. P60–P249. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson D, Johnson C, Castro C, Naswood E, Leon J. Learning Collaborative Summary Report. Los Angeles, Calif: Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health; 2012. CommUNITY Voices: Integrating traditional healing services for urban American Indians/Alaska Natives in Los Angeles County. [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Fisher DG, Reynolds GL, Baig S, Napper LE, Anglin MD. Substance use patterns among high-risk American Indians/Alaska Natives in Los Angeles County. American Journal on Addictions. 2012;21(5):445–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2012.00258.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Johnson CL. Design of a behavioral health program for urban American Indian/Alaska Native youths: A community informed approach. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2011;43(4):337–342. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2011.629152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Johnson CL. Mental health and substance abuse characteristics among a clinical sample of urban American Indian/Alaska Native youths in a large California metropolitan area: A descriptive study. Community Mental Health Journal. 2012;48(1):56–62. doi: 10.1007/s10597-010-9368-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Moore LA, Rieckmann T, Croy C, Novins DK. Perceptions and utilization of motivational interviewing among substance use disorder treatment programs for American Indians/Alaska Natives. Manuscript under review. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson DL, Venner KL, Duran B, Annon JJ, Hale B, Funmaker G. Drum-Assisted Recovery Therapy for Native Americans (DARTNA): Results from a pretest and focus groups. American Indian and Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2014;21(1):35–58. doi: 10.5820/aian.2101.2014.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran E, Duran B. Native American post-colonial psychology. New York, NY: Suny Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Campbell T, Lindhorst T, Huang B, Walters KL. Interpersonal violence in the lives of urban American Indian and Alaska Native women: Implications for health, mental health, and help seeking. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(8):1416–1422. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.054213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldstein Ewing SW, Walters S, Baer JS. Approaching group MI with adolescents and young adults: Strengthening the developmental fit. In: Wagner CCI, Ingersoll KS, editors. Motivational Interviewing in Groups. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2012. pp. 387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher PA, Ball TJ. Tribal participatory research: Mechanisms of a collaborative model. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;32:207–216. doi: 10.1023/b:ajcp.0000004742.39858.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilder DA, Luna JA, Calac D, Moore RS, Monti PM, Ehlers CL. Acceptability of the use of motivational interviewing to reduce underage drinking in a Native American community. Substance Use & Misuse. 2011;46(6):836–842. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2010.541963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1(1):91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James MA. The state of Native America: Genocide, colonization, and resistance. Cambridge, MA: South End Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- LaFromboise TD, Berman JS, Sohi BK. American Indian women. In: Comas-Dizam L, Green B, editors. Women of color: Integrating ethnic and gender identities in psychotherapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1994. pp. 30–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lane DC, Simmons J. American Indian youth substance abuse: Community-driven interventions. Mount Sinai Journal of Medicine. 2011;78(3):362–372. doi: 10.1002/msj.20262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson C, Schlundt D, Patel K, Goldzweig I, Hargreaves M. Community participation in health initiatives for marginalized populations. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2009;32(4):264–270. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0b013e3181ba6f74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Minkler M, Wallerstein N. Community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Myhra LL. "It runs in the family": Intergenerational transmission of historical trauma among urban American Indians and Alaska Natives in culturally specific sobriety maintenance programs. American Indian Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2011;18(2):17–40. doi: 10.5820/aian.1802.2011.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Native American Health Center. Native vision: A focus on improving behavioral health wellness for California Native Americans - California Reducing Disparities Project (CRDP) Native American population report. Oakland, Calif: Native American Health Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Norris T, Vines PL, Hoeffel EM. The American Indian and Alaska Native population: 2010 census briefs. 2012 http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-10.pdf. Retrieved from.

- Rollnick S, Miller WR, Butler CC. Motivational interviewing in health care: Helping patients change behavior. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Smokowski PRJ, Evans CB, Cotter KL, Webber KC. Ethnic identity and mental health in American Indian youth: Examining mediation pathways through self-esteem, and future optimism. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2014;43(3):343–355. doi: 10.1007/s10964-013-9992-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SocioCultural Research Consultants, L. Dedoose Version 5.0.11: Web application for managing, analyzing, and presenting qualitative and mixed method research data. Los Angeles, Calif: SocioCultural Research Consultants, LLC; 2014. Retrieved from www.dedoose.com. [Google Scholar]

- Stumblingbear-Riddle G, Romans JSC. Resilience among urban American Indian adolescents: Exploration into the role of culture, self-esteem, subjective well-being, and social support. American Indian Alaska Native Mental Health Research. 2012;19(2):1–19. doi: 10.5820/aian.1902.2012.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) Motivational Interviewing. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin K, Walker RD, Grover J, Arquette W, Stewart P. Trainer’s guide to motivational interviewing: Enhancing motivation for change—A learner’s manual for the American Indian/Alaska Native counselor. Portland, OR: One Sky Center; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Venner KL, Feldstein SW, Tafoya N. Helping clients feel welcome: Principles of adapting treatment cross-culturally. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2007;25(4):11–30. doi: 10.1300/J020v25n04_02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiland BJ, Nigg JT, Welsh RC, Yau WY, Zubieta JK, Zucker RA, et al. Resiliency in adolescents at high risk for substance abuse: Flexible adaptation via subthalamic nucleus and linkage to drinking and drug use in early adulthood. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2012;36(8):1355–1364. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2012.01741.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitesell NR, Beals J, Crow CB, Mitchell CM, Novins DK. Epidemiology and etiology of substance use among American Indians and Alaska Natives: Risk, protection, and implications for prevention. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2012;38(5):376–382. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.694527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams T. Quietly American Indians reshape cities and reservations. [April 13, 2013];New York Times. 2013 Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/04/14/us/as-americanindians-move-to-cities-old-and-new-challenges-follow.html?_r=0. [Google Scholar]

- Wingo AP, Ressler KJ, Bradley B. Resilience characteristics mitigate tendency for harmful alcohol and illicit drug use in adults with a history of childhood abuse: A cross-sectional study of 2024 inner-city men and women. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2014;51:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright S, Nebelkopf E, Jim N. Epidemiological profile of California American Indian substance abuse consequences and consumption patterns. Oakland, Calif: Native American Health Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]