Abstract

Introduction

Recurrent cancer is common, costly, and lethal, yet we know little about it in community-based populations. Electronic health records (EHR) and tumor registries contain vast amounts of data regarding community-based patients, but usually lack recurrence status. Existing algorithms that use structured data to detect recurrence have limitations.

Methods

We developed algorithms to detect the presence and timing of recurrence after definitive therapy for stages I-III lung and colorectal cancer using two data sources that contain a widely available type of structured data (claims or EHR encounters) linked to gold standard recurrence status: Medicare claims linked to the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance study, and the Cancer Research Network Virtual Data Warehouse linked to registry data. Twelve potential indicators of recurrence were used to develop separate models for each cancer in each data-source. Detection models maximized area under the ROC curve (AUC); timing models minimized average absolute error. Algorithms were compared by cancer type/data-source, and contrasted with an existing binary detection rule.

Results

Detection model AUC’s (>0.92) exceeded existing prediction rules. Timing models yielded absolute prediction errors that were small relative to follow-up time (<15%). Similar covariates were included in all detection and timing algorithms, though differences by cancer-type and dataset challenged efforts to create one common algorithm for all scenarios.

Conclusions

Valid and reliable detection of recurrence using big data is feasible. These tools will enable extensive, novel research on quality, effectiveness, and outcomes for lung and colorectal cancer patients and those who develop recurrence.

Keywords: cancer recurrence, outcomes, lung cancer, colorectal cancer, big data

INTRODUCTION

Over the past few decades there have been substantial improvements in survival for patients with most types of cancer.1 Now, more than two-thirds of cancer patients live at least five years, and many cancer-related deaths are caused by recurrent rather than de novo stage IV disease. As the treatments available for early-stage cancer expand and change, patients who develop recurrence are growing increasingly distinct from those with stage IV disease. Clinical trials help inform treatment decisions for patients with metastatic cancer, but they usually group stage IV and recurrent cases together. Moreover, most cancer patients are treated in the community, where patient characteristics and outcomes often differ notably from those seen in clinical trials.2

With substantial growth in the cost and complexity of cancer therapy, comparative effectiveness studies of representative populations have become essential tools for efficiently identifying optimal treatment strategies among community-based patients. These observational studies address important questions that randomized clinical trials cannot tackle. Unfortunately, the large datasets used for these studies, including electronic health records (EHRs) and accredited cancer registries usually do not capture reliable information regarding recurrence status. Frequently, the investigators who use these datasets employ simple programming rules to detect recurrence3–5, but these rules have often not been tested for validity. It is critical that we develop tools that differentiate between patients with recurrence versus those who were diagnosed with stage IV disease.6

To address this gap of a needed observable outcome several studies recently assessed the sensitivity and specificity of structured data as tools for recurrence detection.3,5–12 Past studies were limited to a single type of cancer5,9–13; had small samples11,12; did not include a gold-standard measure of recurrence3; and lacked detail regarding the characteristics of the incident tumor and its treatment8. We previously demonstrated that two published recurrence detection strategies had unacceptably low sensitivity and specificity when applied to population-based data.14

The aims of this study were to develop simple, parsimonious, accurate tools for detecting recurrent lung and colorectal cancer using structured data elements from readily available datasets generated for clinical and administrative purposes. We were not trying to predict which patients would develop recurrence, but rather to develop tools that could detect who had recurrence to facilitate outcomes research and population health management efforts. To extend our previous work14 with a pair of unique data sets that each contain claims or EHR-based encounters linked to gold standard recurrence status, we 1) expanded the list of potential indicators of recurrence beyond the secondary malignant neoplasm and chemotherapy codes used previously; 2) developed a flexible tool that could generate a probability of detecting recurrence rather than an absolute characterization of recurrence status; and, 3) separately estimated the timing of the recurrence event.

METHODS

Data Sources

The Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance (CanCORS) Consortium is a large, prospective, population and health-system based study of the care provided to and outcomes experienced by lung and colorectal cancer patients diagnosed 2003–2005 and followed through 201115,16. These data were linked to Medicare fee-for-service claims from 2002–2011. The Cancer Research Network (CRN; http://crn.cancer.gov/) is a consortium of health maintenance organizations (HMO) affiliated with the HMO Research Network (HMORN) and the NCI. Two CRN sites, whose certified tumor registrars collect high quality recurrence data, contributed to this analysis: Kaiser Permanente Colorado, Denver, CO, and Kaiser Permanente Northwest, Portland, OR. The HMO-CRN maintains a Virtual Data Warehouse (VDW)14 that links tumor registry data, diagnosis and procedure codes documented in an EPIC®-based EHR, and claims for services delivered by contract providers. Two key differences between the data sources are worth noting: 1) CanCORS enrolled only those patients who consented to participate in the research study whereas the HMO-CRN sample included all patients who received care at a participating HMO; and 2) the former data source included fee-for-service claims whereas the latter collected mostly EHR-based data. Institutional Review Boards from the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center and the participating HMO-CRN sites provided project oversight.

Study Cohort and Recurrence Status

All patients were diagnosed with stage I–III lung or colorectal cancer (excluding stage IIIb lung cancer) at ≥21 years of age. To maximize the applicability of our analysis, we used data available in cancer registries to exclude as few patients as possible. We limited the cohort to patients who 1) had no previous cancer; 2) completed definitive local-regional therapy for their incident lung or colorectal cancer diagnosis; and 3) survived and were followed for at least 30 days after definitive therapy. A small proportion of CanCORS/Medicare patients were excluded, because their recurrence status was missing (9% of lung and 12% of colorectal cases); HMO-CRN/VDW patients did not have missing recurrence status. Patients who developed second primary cancers, based on tumor registry data, were censored because of the possibility that codes generated from these events could have suggested recurrence.

CanCORS/Medicare patients diagnosed 2003–5 were followed until death, the date last known to be recurrence free, or study end date (12/31/11). They must have had at least one Medicare claim and no more than 2 consecutive months without Medicare enrollment. HMO-CRN/VDW patients diagnosed 1/1/00–12/31/11 and captured in the tumor registry were followed through death, disenrollment, or study end date (12/31/12). Gold-standard recurrence was derived from the abstracted medical record or tumor registry, as described previously.14,17 Patients with no documented recurrence who died from any cause were considered non-recurrent. [To apply these algorithms using cancer registry data see Supplemental Materials 1.]

Potential Indicators of Recurrence

The codes considered to be potential detectors of recurrence came from our previous research14, our clinical experience, and studies conducted by others11,12. They were grouped into 12 conceptually homogenous categories (Table 1), and represented several commonly used data standards (ICD-9-CM, ICD-10, CPT-4, HCPCS, NDC, DRGs, BETOS, and facility revenue centers; Supplemental Materials 2). Medicare codes were extracted from the Hospital, Physician, Outpatient Facility, Durable Medical Equipment, Hospice, and Home Health Agency files. The "claim through date" (the last day on the billing statement covering services rendered to the beneficiary) was used to assign a date to each code, except for the Hospital file where the discharge date was used. HMO-CRN codes and their corresponding event dates were extracted from the VDW procedure, diagnosis, encounter, pharmacy, and infusion files.18,19

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics and the Distributions of Potential Indicators of Recurrence

| Lung Cancer |

Colorectal Cancer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMO-CRN/VDW | CanCORS/Medicare | HMO-CRN/VDW | CanCORS/Medicare | ||

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||

| Cohort Assembly | Eligible patients | 792 | 308 | 2827 | 600 |

| Recurrences | 216 | 89 | 355 | 84 | |

| Median follow-up* (months) | 33 Range 1–152 | 19 Range 1 to 99 | 45 Range 1–156 | 19 Range 1 to 103 | |

| Patient Characteristics | Age ≥ 65 | 484 (61) | 268 (87) | 1667 (59) | 556 (93) |

| Female | 415 (52) | 148 (48) | 1410 (50) | 294 (49) | |

| Non-White | 131 (17) | 42 (14) | 583 (21) | 162 (27) | |

| Co-morbidities | 0 | 283 (36) | 74 (24) | 1559 (55) | 267 (45) |

| 1 | 277 (35) | 115 (37) | 641 (23) | 189 (32) | |

| 2+ | 232 (29) | 119 (39) | 627 (22) | 144 (24) | |

| Stage at diagnosis | I | 512 (65) | 220 (71) | 953 (34) | 186 (31) |

| II | 145 (18) | 53 (17) | 1009 (36) | 216 (36) | |

| III | 135 (17) | 35 (11) | 865 (31) | 198 (33) | |

| % having died | At median follow-up | 27% | 18% | 18% | 13% |

| Potential Indicators of Recurrence | |||||

| Secondary malignancy neoplasm EXcluding lymph node codes | 0 | 625 (79) | 209 (68) | 2438 (86) | 434 (72) |

| 1 | 38 (5) | 29 (9) | 88 (3) | 62 (10) | |

| 2+ | 135 (17) | 70 (23) | 301 (11) | 104 (17) | |

| Secondary malignancy neoplasm INcluding lymph node codes | 0 | 499 (63) | 186 (60) | 1947 (69) | 344 (57) |

| 1 | 59 (7) | 32 (10) | 171 (6) | 115 (19) | |

| 2+ | 234 (30) | 90 (29) | 709 (25) | 141 (24) | |

| Chemotherapy† | 0 | 371 (47) | 154 (50) | 1323 (47) | 308 (51) |

| 1 | 92 (12) | 21 (7) | 266 (9) | 50 (8) | |

| 2+ | 329 (42) | 133 (43) | 1238 (44) | 242 (40) | |

| Radiation therapy† | 0 | 533 (67) | 228 (74) | 2337 (83) | 546 (91) |

| 1 | 43 (5) | 6 (2) | 115 (4) | 5 (1) | |

| 2+ | 216 (27) | 74 (24) | 375 (13) | 49 (8) | |

| Hospice | 0 | 662 (84) | 241 (78) | 2556 (90) | 542 (90) |

| 1+ | 130 (16) | 67 (22) | 271 (10) | 58 (10) | |

| High cost imaging | Mean per year‡ | 2.26 (SD 2.33) | 3.27 (SD 3.44) | 1.12 (SD 1.70) | 2.23 (SD 2.97) |

| Symptom of cancer | Mean per year‡ | 1.04 (SD 2.86) | 2.24 (SD 5.47) | 0.41 (SD 1.80) | 2.25 (SD 10.84) |

| Pain¶ | Mean per year‡ | 6.07 (SD 8.05) | 0.23 (SD 0.90) | 2.63 (SD 4.40) | 0.21 (SD 0.44) |

| Inpatient§ | Mean per year‡ | 3.52 (SD 6.01) | 1.19 (SD 1.89) | 1.81 (SD 3.54) | 0.90 (SD 1.61) |

| Observation§ | Mean per year‡ | 0.09 (SD 0.42) | 0.04 (SD 0.24) | 0.07 (SD 0.31) | 0.03 (SD 0.20) |

| Emergency Department§ | Mean per year‡ | 0.91 (SD 1.66) | 0.58 (SD 1.07) | 0.65 (SD 1.55) | 0.44 (SD 0.94) |

| Any procedure | Mean per year‡ | 31.75 (SD 20.91) | 47.80 (SD 31.92) | 25.37 (SD 20.12) | 41.75 (SD 37.32) |

From date of definitive local therapy the earlier of study end date (12/31/2012 for HMO-CRN and 12/31/2011 for CanCORS/Medicare); date of death; date of last follow up; date of second primary cancer diagnosis; and date patient was last confirmed to be recurrence-free (applicable for CanCORS/Medicare data only; ascertainment of gold standard recurrence status was not through the patient's date of death for all patients).

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy events occurring within 6 months after a lung cancer or within 12 months after a colorectal cancer diagnosis were excluded when deriving potential indicators of recurrence, because they were considered therapy for the primary cancer.

Mean number of days with the indictor per year of follow up. SD=standard deviation.

Hospital encounters were separated into three mutually exclusive groups: inpatient (including ED or observation leading to inpatient), observation (including ED leading to observation), and ED only.

The mean number of pain scores per year was lower in the CanCORS/Medicare vs. HMO-CRN/VDW dataset, because the variable was derived from NDC and HCPCS codes for narcotic/pain medications. The VDW data source captured ambulatory pharmacy dispenses, whereas the Medicaid data source did not (i.e., part D data were not available for this analysis).

The unit of analysis was the code date. If a code was present in multiple files on the same date, it was only counted once. Codes were considered potential indicators of recurrence if they fell after definitive therapy and before the end of follow up. However, chemotherapy and radiation therapy codes that occurred within 6 (lung cancer) or 12 (colorectal) months after the index diagnosis were excluded, because they could represent primary cancer therapy. Indicators were classified as categorical variables, unless the code count increased over time irrespective of recurrence status, in which case they were classified as continuous and standardized by the duration of follow-up.

Algorithm Development and Evaluation

We expected to find meaningful differences between lung and colorectal cancer patients, so we developed separate algorithms for each cancer. We also expected the CanCORS/Medicare claims and HMO-CRN/VDW EHR data would differ, so we developed separate algorithms for each data source. To investigate whether the aforementioned differences between the data sources affected algorithm performance we assessed the performance of each algorithm using independent data from the other source. Most importantly, we split our recurrence detection effort into two phases: 1) identify patients who had recurrence within a given time-period; and, 2) determine the timing of recurrence among patients considered to have recurred. We believed the variables that were optimal for recurrence detection might be different from those that were optimal for recurrence timing.

For phase 1, we used logistic regression modeling to generate a probability of having recurred using codes incurred during follow-up, with the goal of maximizing the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC). Using all possible combinations of the 12 indicators, plus cancer stage and duration of follow-up, we derived a series of candidate models. We evaluated the performance of each candidate across the full range of threshold probabilities (0–1). To avoid selecting a model that over fit our data, we used Monte-Carlo cross-validation to estimate the AUROC for each potential model.20 When multiple models yielded AUROC values that were almost identical (i.e., within the error of the Monte-Carlo procedure), we selected the model with the fewest predictors.

Model performance was summarized using accuracy, the Youden-Index (sensitivity + specificity) 21, and AUROC. We reported the threshold probabilities that maximized accuracy and Youden-Index; and the sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values at these threshold probabilities, each calculated using the cross-validation procedure described above. A bootstrap percentile method was used to derive 95% confidence intervals.22 Calibration plots were generated to confirm that the predicted and observed probabilities were close. Specifically, patients were categorized into predicted probability deciles, and the average predicted probability was plotted against the proportion of observed recurrences. To evaluate the incremental value of the derived algorithms over an existing binary classification rule14, we calculated the difference in AUROC’s.

For phase 2, we developed an algorithm to determine the timing of recurrence among patients who recurred according to the gold-standard.23 The same 12 categories described above were included as potential indicators. For each category, we determined when the code-count peaked, and we derived an adjustment factor to account for systematic differences between this and the true recurrence date. Thus, each patient could have up to 12 estimated recurrence times. We generated a series of candidate algorithms using all possible combinations of categories. For each candidate, we weighted and integrated the estimates from all the included categories to derive a single estimated recurrence time. Our goal was to identify the algorithm that minimized the absolute detection error (AE), defined as the mean of the absolute difference between the predicted and actual recurrence dates across all true-positives. Again, we used Monte-Carlo cross-validation to estimate the AE’s and determine the best model. Similar to Part 1, a final model was chosen based on parsimony from among the candidates that offered similarly high performance.

The correct classification rate (CCR) was calculated to measure overall algorithm performance. Also, we evaluated the performance of each algorithm using independent data from the other data source. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) and R version 3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). All tests of statistical significance were two-sided. [Additional algorithm development and assessment methods are in Supplemental Materials 3.]

RESULTS

The CanCORS/Medicare sample included 308 lung and 600 colorectal cancer cases, each followed for a median of 19 months. The proportions of patients who recurred were 29% and 14%, respectively. The HMO-CRN/VDW sample included 792 lung and 2,827 colorectal cancer cases followed for a median of 33 and 45 months, respectively. Despite longer follow-up, the HMO-CRN/VDW recurrence proportions (27% and 13%) were similar to those of the CanCORS/Medicare sample. The 3-year probabilities of death were 38% and 29% for lung cancer, and 26% and 15% for colorectal cancer, for CanCORS/Medicare and HMO-CRN/VDW respectively. Stage distributions across the data sources were similar. The HMO-CRN/VDW cohorts demonstrated lower rates of recurrence and fewer deaths, perhaps due in part to the CanCORS/Medicare cohort’s older age, more frequent co-morbidities, and shorter median follow-up. Also, CanCORS followed consented patients wherever they received care; whereas the HMO-CRN followed enrollees only so long as they continued to receive care from the same health plan. Of the 12 potential indicators (Table 1), five were coded categorically and seven were coded continuously. Codes for cancer symptoms and procedures appeared more frequently in CanCORS/Medicare versus HMO-CRN/VDW cases; codes for pain, inpatient stays and emergency department visits were less frequent. Cancer treatment and Hospice codes were not substantially different across data sources. Radiation therapy and hospice were more common among lung versus colorectal cases.

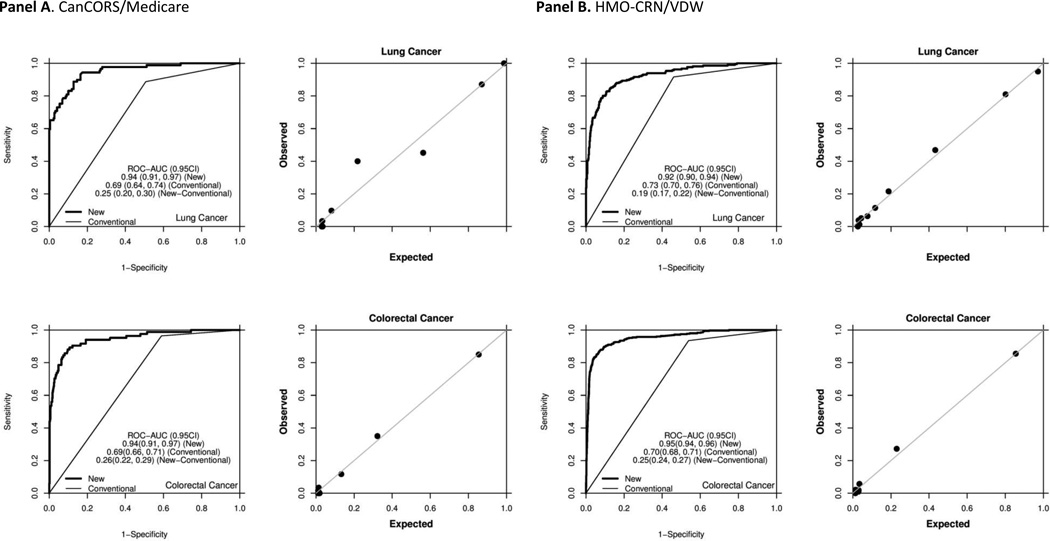

The CanCORS/Medicare phase 1 algorithms for lung and colorectal cancer included four variables and yielded AUROC estimates of 0.940 and 0.945, respectively (Table 2; Figure 1). The HMO-CRN/VDW phase 1 algorithms for lung and colorectal cancer also included four variables and yielded AUROC estimates of 0.924 and 0.953, respectively (Table 3; Figure 1). As expected, the estimated probability of recurrence increased from stage I to stage III for lung cancer (e.g., 0.22 to 0.47 in CanCORS/Medicare) and colorectal cancer (e.g., 0.04 to 0.22 in HMO-CRN/VDW). The proportions of recurrences whose time was correctly classified within 6 months were 81% for lung and 85% for colorectal cancer in CanCORS/Medicare (Table 2), and 75% for lung and 71% for colorectal cancer in the HMO-CRN/VDW (Table 3). CanCORS/Medicare CCR’s were higher, because of the cohort’s shorter follow-up. After controlling for duration of follow-up, CCR’s were similar.

Table 2.

CanCORS/Medicare lung and colorectal cancer algorithm components and performance*

| PHASE I ALGORITM (recurrence status) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Variable | Categories | OR | (95% CI) | P | OR | (95% CI) | P |

| (Intercept) | -- | 0.03 | (0.01, 0.07) | <0.001 | 0.01 | (0.01, 0.02) | <0.001 | |

| Secondary malignancy INcluding nodes | <2 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 2+ | 8.02 | (3.38, 19.04) | <0.001 | 20.17 | (9.22, 44.11) | <0.001 | ||

| Radiation | <2 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 2+ | 7.10 | (2.88, 17.47) | <0.001 | 4.86 | (1.89, 12.48) | 0.001 | ||

| Hospice | 0 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 1+ | 48.57 | (17.27, 136.64) | <0.001 | 24.65 | (9.89, 61.44) | <0.001 | ||

| Imaging (# per year) | continuous | 1.05 | (0.94, 1.17) | 0.42 | 1.12 | (1.02, 1.22) | 0.01 | |

| Performance† | Measure | Estimate (95% CI) | ||||||

| ROC-AUC | 0.940 (0.907,0.968) | 0.945 (0.915, 0.970) | ||||||

| To maximize accuracy | To maximize Youden index | To maximize accuracy | To maximize Youden index | |||||

| Cutoff | 56.6% | 26.2% | 47.0% | 19.6% | ||||

| Accuracy | 0.901 (0.880, 0.937) | 0.873 (0.844, 0.925) | 0.938 (0.923, 0.959) | 0.902 (0.865, 0.936) | ||||

| Youden Index | 0.723 (0.650, 0.833) | 0.769 (0.724, 0.850) | 0.691 (0.577, 0.805) | 0.804 (0.740, 0.873) | ||||

| Sensitivity | 0.772 (0.686, 0.885) | 0.911 (0.849, 0.961) | 0.717 (0.593, 0.837) | 0.902 (0.848, 0.958) | ||||

| Specificity | 0.951 (0.920, 0.983) | 0.858 (0.819, 0.933) | 0.974 (0.960, 0.990) | 0.902 (0.858, 0.939) | ||||

| Positive Predictive Value | 0.882 (0.836, 0.949) | 0.735 (0.659, 0.859) | 0.833 (0.782, 0.919) | 0.613 (0.508, 0.728) | ||||

| Negative Predictive Value | 0.914 (0.891, 0.954) | 0.961 (0.935, 0.984) | 0.955 (0.940, 0.974) | 0.983 (0.972, 0.993) | ||||

| PHASE II ALGORITM (timing of recurrence) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

| Components | Variable | Offset (months)§ | Weight¶ | Offset (months)§ | Weight¶ | |||

| Secondary malignancy INcluding nodes | 0.22 | 0.279 | −0.07 | 0.387 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 1.21 | 0.296 | 3.69 | 0.500 | ||||

| Imaging | −0.94 | 0.425 | −1.08 | 0.113 | ||||

| OVERALL PERFORMANCE ‡ (Phases I and II combined) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

| Number of | True positives | 58 | 59 | |||||

| False negatives | 31 | 25 | ||||||

| False positives | 1 | 14 | ||||||

| True negatives | 218 | 502 | ||||||

| Average absolute error | Error (months) | Standardized error (%)# | Error (months) | Standardized error (%)# | ||||

| Error in estimated time of recurrence | 3.7 | 15.2 | 3.9 | 13.1 | ||||

| Correct classification rate | Time window | Cumulative N (%) | Cumulative N (%) | |||||

| ≤ 1 month | 21 (36.2) | 13 (22.0) | ||||||

| ≤ 2 months | 26 (44.8) | 23 (39.0) | ||||||

| ≤ 3 months | 36 (62.1) | 31 (52.5) | ||||||

| ≤ 4 months | 39 (67.2) | 41 (69.5) | ||||||

| ≤ 5 months | 45 (77.6) | 46 (78.0) | ||||||

| ≤ 6 months | 47 (81.0) | 50 (84.7) | ||||||

| >6 months | 11 (19.0) | 9 (15.3) | ||||||

Abbreviations: OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; ROC-AUC=receiver operating characteristics area under the curve.

ROC-AUC and performance estimate confidence intervals derived from the primary dataset using cross-validation techniques.

Overall performance estimates were generated using the derivation dataset and the phase 1 algorithm cutoffs that maximized accuracy. Average absolute error and correct classification calculations were based on the subset of patients who were classified as true positives.

The offset represents the average of the difference between the time when the component variable count peaked and the time of the gold standard recurrence negative values indicate that the peak in the component variable was before the gold standard recurrence date.

The weight is the amount a component variable’s estimated recurrence date contributed to estimated date of recurrence.

The average absolute error in months divided by the average duration of follow-up in months.

Figure 1.

Performance of phase I recurrence detection algorithms: ROC curves and calibration plots. “New” denotes the novel phase I recurrence detection algorithm. “Conventional” denotes a binary classification rule where patients with any diagnostic code for secondary malignant neoplasm or any procedure/medication code for chemotherapy are classified as recurrent, and all others are classified as non-recurrent.

Panel A. CanCORS/Medicare

Panel B. HMO-CRN/VDW

Table 3.

HMO-CRN/VDW lung and colorectal cancer algorithm components and performance*

| PHASE I ALGORITM (recurrence status) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Components | Variable | Categories | OR | (95% CI) | P | OR | (95% CI) | P |

| (Intercept) | -- | 0.03 | (0.02, 0.04) | <0.001 | 0.01 | (0.01, 0.02) | <0.001 | |

| Secondary malignancy EXcluding nodes | 0 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 1 | 12.54 | (5.29, 29.69) | <0.001 | 17.92 | (10.61, 30.25) | <0.001 | ||

| 2+ | 20.54 | (10.84, 38.49) | <0.001 | 80.19 | (52.24, 123.10) | <0.001 | ||

| Chemotherapy | <2 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 2+ | 3.28 | (2.02, 5.32) | <0.001 | 2.13 | (1.42, 3.20) | <0.001 | ||

| Hospice | 0 | 1.00 | -- | 1.00 | -- | |||

| 1+ | 6.92 | (3.81, 12.54) | <0.001 | 5.94 | (3.74, 9.44) | <0.001 | ||

| Imaging (# per year) | continuous | 1.37 | (1.24, 1.53) | <0.001 | 1.13 | (1.04, 1.22) | 0.004 | |

| Performance† | Measure | Estimate (95% CI) | ||||||

| ROC-AUC | 0.924 (0.902, 0.945) | 0.953 (0.939, 0.965) | ||||||

| To maximize accuracy | To maximize Youden index | To maximize accuracy | To maximize Youden index | |||||

| Cutoff | 42.9% | 22.8% | 51.2% | 07.7% | ||||

| Accuracy | 0.889 (0.873, 0.911) | 0.869 (0.848, 0.899) | 0.951 (0.943, 0.959) | 0.918 (0.900, 0.939) | ||||

| Youden Index | 0.697 (0.640, 0.763) | 0.733 (0.690, 0.788) | 0.743 (0.696, 0.796) | 0.812 (0.779, 0.846) | ||||

| Sensitivity | 0.761 (0.693, 0.831) | 0.861 (0.811, 0.906) | 0.766 (0.719, 0.821) | 0.890 (0.855, 0.921) | ||||

| Specificity | 0.936 (0.916, 0.964) | 0.872 (0.839, 0.914) | 0.977 (0.969, 0.984) | 0.922 (0.900, 0.949) | ||||

| Positive Predictive Value | 0.821 (0.782, 0.888) | 0.721 (0.663, 0.797) | 0.830 (0.788, 0.873) | 0.628 (0.564, 0.715) | ||||

| Negative Predictive Value | 0.914 (0.892, 0.937) | 0.944 (0.925, 0.963) | 0.967 (0.960, 0.975) | 0.983 (0.978, 0.988) | ||||

| PHASE II ALGORITM (timing of recurrence) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

| Components | Variable | Offset (months)§ | Weight¶ | Offset (months)§ | Weight¶ | |||

| Secondary malignancy EXcluding nodes | 0.93 | 0.264 | 1.75 | 0.297 | ||||

| Chemotherapy | 1.55 | 0.379 | 2.61 | 0.460 | ||||

| Imaging | −0.46 | 0.357 | −0.62 | 0.243 | ||||

| OVERALL PERFORMANCE ‡ (Phases I and II combined) | LUNG CANCER | COLORECTAL CANCER | ||||||

| Number of: | True positives | 165 | 263 | |||||

| False negatives | 51 | 92 | ||||||

| False positives | 40 | 50 | ||||||

| True negatives | 536 | 2422 | ||||||

| Average absolute error | Error (months) | Standardized error (%)# | Error (months) | Standardized error (%)# | ||||

| Error in estimated time of recurrence | 4.4 | 14.6 | 5.5 | 12.7 | ||||

| Correct classification rate | Time window | Cumulative N (%) | Cumulative N (%) | |||||

| ≤ 1 month | 59 (35.8) | 53 (20.2) | ||||||

| ≤ 2 months | 84 (50.9) | 102 (38.8) | ||||||

| ≤ 3 months | 98 (59.4) | 130 (49.4) | ||||||

| ≤ 4 months | 111 (67.3) | 151 (57.4) | ||||||

| ≤ 5 months | 121 (73.3) | 170 (64.6) | ||||||

| ≤ 6 months | 124 (75.2) | 186 (70.7) | ||||||

| >6 months | 41 (24.8) | 77 (29.3) | ||||||

Abbreviations: OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; ROC-AUC=receiver operating characteristics area under the curve.

ROC-AUC and performance estimate confidence intervals derived from the primary dataset using cross-validation techniques.

Overall performance estimates were generated using the derivation dataset and the phase 1 algorithm cutoffs that maximized accuracy. Average absolute error and correct classification calculations were based on the subset of patients who were classified as true positives.

The offset represents the average of the difference between the time when the component variable count peaked and the time of the gold standard recurrence negative values indicate that the peak in the component variable was before the gold standard recurrence date.

The weight is the amount a component variable’s estimated recurrence date contributed to estimated date of recurrence.

The average absolute error in months divided by the average duration of follow-up in months.

We applied each CanCORS/Medicare-derived algorithm to data from the HMO-CRN/VDW for the corresponding cancer type, and did the same for each HMO-CRN/VDW-derived algorithm. For the phase 1 models the AUROC’s did not differ substantially, although subtle differences were observed (Supplemental Materials 4). Applying CanCORS/Medicare-derived algorithms to HMO-CRN/VDW data yielded more false negatives, and applying HMO-CRN/VDW-derived algorithms to CanCORS/Medicare data yielded more false positives. For the phase 2 algorithms, only modest differences were seen when applying algorithms derived from one data source to the other, except when the HMO-CRN/VDW-derived colorectal cancer algorithm was applied to CanCORS/Medicare data.

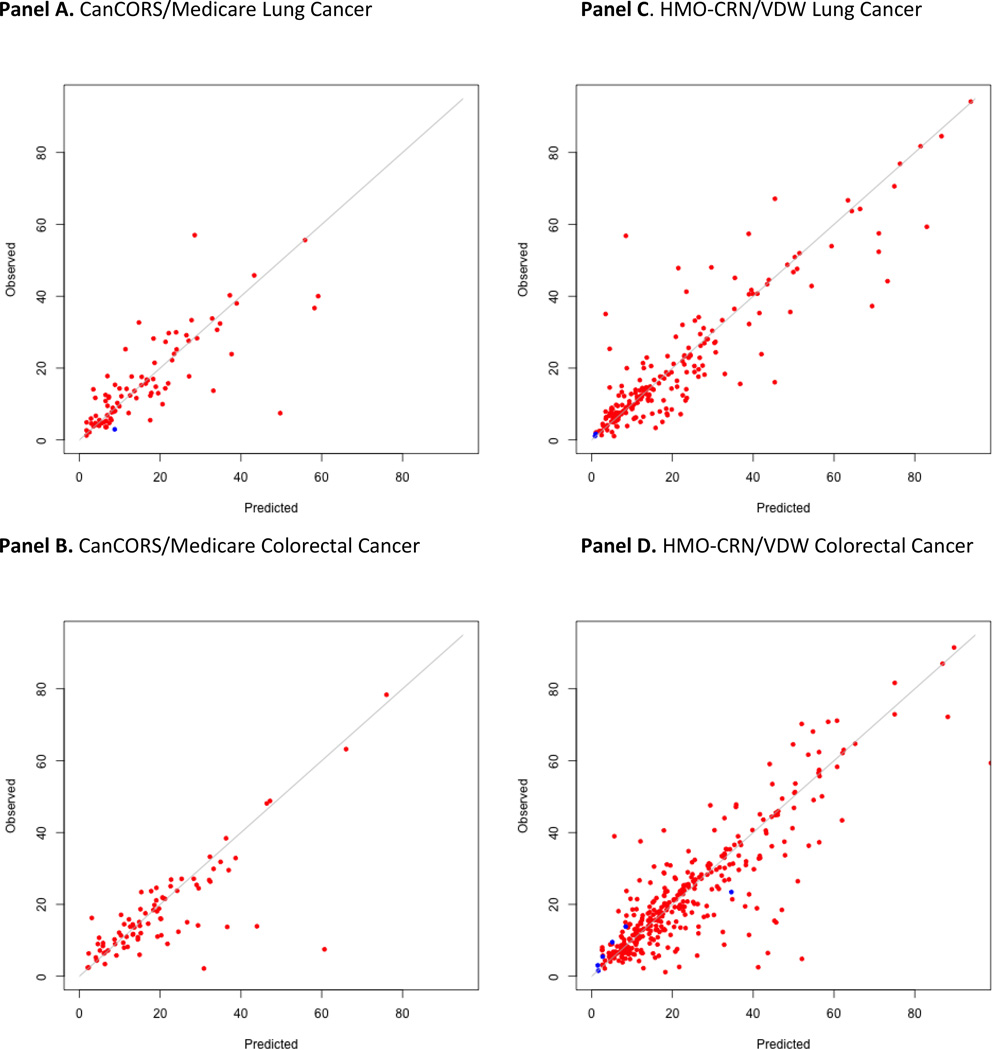

Compared to a previously described binary detection rule based on secondary malignancy and chemotherapy codes, all phase 1 algorithms demonstrated significantly improved performance, with increases in the AUROC ranging from 0.18 to 0.25 (Figure 1). Even when algorithms developed for one data source were applied to another data-source, the AUROC still improved (Supplemental Materials 4). We were able to determine the timing of recurrence within 6 months for >80% of patients. Importantly, all calibration plots reassuringly demonstrated that the predicted and actual probabilities were very close (Figures 1–2).

Figure 2.

Phase II algorithm: observed versus predicted time of recurrence (in months from diagnosis) among patients with recurrence as defined by the gold-standard. Red dots represent patients for whom the phase 1 algorithm detected recurrence. Blue dots represent patients for whom the phase 1 algorithm did not detect recurrence.

Panel A. CanCORS/Medicare Lung cancer

Panel B. CanCORS/Medicare Colorectal Cancer

Panel C. HMO-CRN/VDW Lung cancer

Panel D. HMO-CRN/VDW Colorectal Cancer

CONCLUSIONS

We developed algorithms that detect recurrence among patients who completed definitive therapy for stage I-III lung or colorectal cancer using structured data from fee-for-service claims and EHR-based encounters. Several unique and favorable features differentiate our algorithms from prior published work.6 Using a threshold probability above which cases are classified as having recurred allows users to optimize sensitivity or specificity depending on the goals of their analysis. A two-phase approach–first detecting recurrence and then determining the timing of recurrence–facilitates comparative effectiveness studies that want to use recurrence as either an outcome or an inclusion criterion. We incorporated several new covariates to help detect recurrence among patients who did not receive cancer-directed therapy at recurrence. This improved algorithm performance without adding substantially to the implementation burden.

We chose a cancer site-specific-approach, because we believed it would produce more accurate results. Interestingly, the final lung and colorectal cancer algorithms used many of the same covariates. The models had only modest, cancer-level differences (e.g., distinct threshold probabilities and covariate weights). Other cancers, such as breast and prostate, have distinct natural histories, more local/biochemical-only recurrences, and unique patterns-of-care. Hence, the optimal recurrence detection algorithms for these cancers could differ from those described above. That having been said, many components of our lung/colorectal cancer algorithms would likely be integral elements of breast/prostate recurrence detection algorithms too (e.g., chemotherapy, hospice), limiting the incremental work needed to apply these tools to patients with other cancers.

Contrasts between the CanCORS/Medicare and HMO-CRN/VDW-derived algorithms were identified, but were less substantial than expected. A total of four total covariates were included in each algorithm, and two covariates were common to both. For CanCORS/Medicare, the secondary malignant neoplasm variable included lymph node sites and was a two category item, whereas for HMO-CRN/VDW, it excluded lymph node sites and was a three category item. Radiation therapy was a part of the CanCORS/Medicare phase 1 algorithms, whereas chemotherapy was a part of the HMO-CRN/VDW phase 1 algorithms. It is not clear whether these modest algorithm differences were more attributable to variation between the cohorts or variation between the data sources. As suggested above, CanCORS/Medicare patients were older, had more co-morbid conditions, were identified via rapid case ascertainment, and had to actively enroll on a study.16 In contrast, HMO-CRN/VDW patients were diagnosed with cancer while enrolled in a capitation-based network, and were linked to EHR-based encounters rather than reimbursement claims.17 The odds ratios for the associations between the covariates and recurrence varied, so the covariate weights in the logistic regression models differed. Since most of the work to implement these algorithms involves extracting the data used to define each covariate, adjusting covariate weights and threshold probabilities is a relative efficient way to customize algorithms.

When we assessed the performance of each algorithm using data for the relevant cancer from the other data source, it was reassuring to see that the AUROC values were similar. Differences in the numbers of false positives and false negatives may have been due to intrinsic differences between the claims/fee-for-service and EHR/capitation-based data sources. During algorithm development, we endeavored to harmonize all phase 1-algorithms around one common set of covariates. Differences were identified, but were less than expected (data not shown). Future endeavors to harmonize these algorithms are worthwhile, and may be made easier as EHR’s incorporate more structured data.

Our phase 2 algorithms were remarkably consistent, even though they were derived from different data sources for different cancer types. All were based on the same three covariates, with the only difference being the inclusion of lymph node sites in the secondary malignancy variable for CanCORS/Medicare. While covariate weights varied, the chemotherapy variable contributed the most to all phase 2 algorithms except for CanCORS/Medicare lung cancer. The accuracy of the estimated timing of recurrence was high for many patients, but suboptimal for a meaningful minority. We believe the current degree of accuracy may be sufficient to use recurrence as an outcome for some studies, but may be insufficient if an inception cohort of patients with recurrence is needed. For these analyses, validating the timing of an event is as important as validating detection of the event.

Compared to pre-existing binary prediction rules, the algorithms that we developed demonstrated improved performance with relative increases of the AUROC of 26%–38%.14 Unlike some previous studies,3,8,9,11,12 we were fortunate to have data for two large, population-based samples of patients with two prevalent cancers; and to have direct measures of recurrence based on manual chart abstraction linked to structured claims/EHR data. Also, our cohorts included patients who represented a range of socio-demographic characteristics and were treated in two distinct care settings (fee-for-service and capitation). The demographic similarity of CanCORS and SEER 16 support the use of our algorithms in SEER-Medicare analyses. We used logistic regression modeling, rather than CART, k-nearest neighbor, or other commonly used statistical classification tools, because we wanted models that explicitly demonstrated how changes in model factors affected recurrence probabilities. We believe the recurrence detection tools described above improve on historical approaches, and offer significant value to investigators who use datasets that link fee-for-service claims and/or EHR-based encounters to cancer registry files.

These benefits notwithstanding, our study has a number of limitations. The duration of follow-up was shorter than the 5-year period during which recurrence typically happens, though it was reassuring to note that time from diagnosis was not an important factor when detecting recurrence. Our approach relied on cancer registry data to identify incident cancer cases; our algorithm was not designed to discriminate between recurrent versus new primary cancer. Patients who had primary progression of their disease, in other words progression before having an opportunity to receive definitive therapy, were excluded using data that many not be available in all cancer registries. More work is needed to study the applicability of our algorithms with other samples, data sources, and cancer types; we are currently conducting additional evaluations using independent data sources. Estimates of the timing of recurrence do not offer sufficient precision; more research is needed to optimize the tools and techniques used to ascertain the timing of events using structured claims/EHR data. While we incorporated hospice and imaging codes to identify patients who received no treatments for their recurrence, more efforts to identify these patients are still warranted.

Recurrence detection tools that use readily available data-sources to identify a key outcome/population of interest have many potentially compelling applications: assess the effectiveness of alternate treatments for patients with early stage or recurrent cancer outside of clinical trials; compare prognostic estimates or treatment strategies for patients with recurrent versus de-novo metastatic disease; develop novel population health-management tools for health care organizations and payers, etc. Tools such as these are critical components of innovative health information technology efforts, such as ASCO’s CancerLinq2 program, that endeavor to transform cancer care though the development of a learning healthcare system. A number of investigators have used natural language processing (NLP) to identify conditions or events from unstructured clinical data. Natural language processing-based algorithms could help detect patients with recurrence.10 However, the most effective solution will likely incorporate all available data, combining what we learn from structured data with what we extract from free-text documentation. More efforts to describe valid, reliable tools through a transparent process are critical if we intend to use big data to foster meaningful, impactful, and long-lasting improvements in outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding:

This work was supported by a grant from the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA172143 to MJH/DR) and an NCI Cooperative Agreement (U19 CA79689 to the Cancer Research Network). The American Society of Clinical Oncology (Career Development Award) and Susan G. Komen for the Cure (Career Catalyst Award) provided salary support to MJH. The work of the CanCORS consortium was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to the Statistical Coordinating Center (U01 CA093344) and the NCI supported Primary Data Collection and Research Centers (Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Cancer Research Network U01 CA093332; Harvard Medical School/Northern California Cancer Center U01 CA093324; University of Iowa U01 CA01013; University of North Carolina U01 CA093326), and by a Department of Veterans Affairs grant to the Durham VA Medical Center VA HSRD CRS-02-164.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013 Jan;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oncology ASoC. [Accessed December 8, 2014];ASCO Institute for Quality. 2014 http://www.instituteforquality.org/cancerlinq.

- 3.Warren JL, Mariotto A, Melbert D, et al. Sensitivity of Medicare Claims to Identify Cancer Recurrence in Elderly Colorectal and Breast Cancer Patients. Med Care. 2013 Dec 26; doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hershman DL, Wright JD, Lim E, Buono DL, Tsai WY, Neugut AI. Contraindicated use of bevacizumab and toxicity in elderly patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013 Oct 1;31(28):3592–3599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.48.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Deshpande AD, Schootman M, Mayer A. Development of a claims-based algorithm to identify colorectal cancer recurrence. Ann Epidemiol. 2015 Apr;25(4):297–300. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Warren JL, Yabroff KR. Challenges and opportunities in measuring cancer recurrence in the United States. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015 Aug;107(8) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anaya DA, Becker NS, Richardson P, Abraham NS. Use of administrative data to identify colorectal liver metastasis. The Journal of surgical research. 2012 Jul;176(1):141–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2011.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nordstrom BL, Whyte JL, Stolar M, Mercaldi C, Kallich JD. Identification of metastatic cancer in claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012 May;21(Suppl 2):21–28. doi: 10.1002/pds.3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuback J, Yu O, Pocobelli G, et al. Administrative Data Algorithms to Identify Second Breast Cancer Events Following Early-Stage Invasive Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012;104(12):931–940. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrell DS, Halgrim S, Tran DT, et al. Using natural language processing to improve efficiency of manual chart abstraction in research: the case of breast cancer recurrence. Am J Epidemiol. 2014 Mar 15;179(6):749–758. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lamont EB, Herndon JE, 2nd, Weeks JC, et al. Measuring disease-free survival and cancer relapse using Medicare claims from CALGB breast cancer trial participants (companion to 9344) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006 Sep 20;98(18):1335–1338. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Earle CC, Nattinger AB, Potosky AL, et al. Identifying cancer relapse using SEER-Medicare data. Med Care. 2002 Aug;40(8 Suppl):IV, 75–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200208001-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dolan MT, Kim S, Shao Y, Lu-Yao G. Authentication of Algorithm to Detect Metastases in Men with Prostate Cancer Using ICD-9 Codes. Epidemiology Research International. 2012;20(7) doi: 10.1155/2012/970406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassett MJ, Ritzwoller DP, Taback N, et al. Validating Billing/Encounter Codes as Indicators of Lung, Colorectal, Breast, and Prostate Cancer Recurrence Using 2 Large Contemporary Cohorts. Med Care. 2012 Dec 6; doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318277eb6f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ayanian JZ, Chrischilles EA, Fletcher RH, et al. Understanding cancer treatment and outcomes: the Cancer Care Outcomes Research and Surveillance Consortium.[see comment][erratum appears in J Clin Oncol. 2004 Dec 15;22 (24)5026] J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):2992–2996. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Catalano PJ, Ayanian JZ, Weeks JC, et al. Representativeness of participants in the cancer care outcomes research and surveillance consortium relative to the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results program. Med Care. 2013 Feb;51(2):e9–e15. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318222a711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ritzwoller DP, Carroll N, Delate T, et al. Validation of electronic data on chemotherapy and hormone therapy use in HMOs. Med Care. 2013 Oct;51(10):e67–e73. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31824def85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross TC, Ng D, Brown JS, et al. The HMO Research Network virtual data warehouse: a public data model to support collaboration. eGEMs (Generating Evidence & Methods to improve patient outcomes) 2014;2(1) doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hornbrook MC, Hart G, Ellis JL, et al. Building a virtual cancer research organization. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2005;(35):12–25. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgi033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Molinaro AM, Simon R, Pfeiffer RM. Prediction error estimation: a comparison of resampling methods. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2005 Jul 14;21(15):3301–3307. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Youden WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer. 1950;3(1):32–35. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(1950)3:1<32::aid-cncr2820030106>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Efron B, Tibshirani R. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall/CRC; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Uno H, Hassett MJ, Cronin A, Hornbrook M, Ritzwoller D. Determining the Timing of Clinical Events Using Structured Data: A Worked Example Focusing on Cancer Recurrence. in preparation. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.