Abstract

The aim of this study is to develop and test the effectiveness of a drinking-motive-tailored intervention for adolescents hospitalized due to alcohol intoxication in eight cities in Germany between December 2011 and May 2012 against a similar, non-motive-tailored intervention. In a randomized controlled trial, 254 adolescents received a psychosocial intervention plus motive-tailored (intervention group; IG) or general exercises (control group; CG). Adolescents in the IG received exercises in accordance with their drinking motives as indicated at baseline (e.g. alternative ways of spending leisure time or dealing with stress). Exercises for the CG contained alcohol-related information in general (e.g. legal issues). The data of 81 adolescents (age: M = 15.6, SD = 1.0; 42.0% female) who participated in both the baseline and the follow-up were compared using ANOVA with repeated measurements and effect sizes (available case analyses). Adolescents reported lower alcohol use at the four-week follow-up independently of the kind of intervention. Significant interaction effects between time and IG were found for girls in terms of drinking frequency (F = 7.770, p < 0.01) and binge drinking (F = 7.0005, p < 0.05) but not for boys. For the former, the proportional reductions and corresponding effect sizes of drinking frequency (d = − 1.18), binge drinking (d = − 1.61) and drunkenness (d = − 2.87) were much higher than the .8 threshold for large effects. Conducting psychosocial interventions in a motive-tailored way appears more effective for girls admitted to hospital due to alcohol intoxication than without motive-tailoring. Further research is required to address the specific needs of boys in such interventions. (German Clinical Trials Register, DRKS ID: DRKS00005588).

Keywords: Alcohol intoxication, Adolescents, Drinking motives, Intervention

Highlights

-

•

Adolescents hospitalized for alcohol intoxication reported lower alcohol use 4 weeks after the psychosocial intervention.

-

•

For girls, the intervention was even more effective when motive-tailored.

-

•

For boys, there was no significant effect of the motive-tailored intervention additional to HaLT.

Introduction

Alcohol use is the number one risk factor for morbidity and mortality among young people in established market economies (Rehm et al., 2006). Comparing different risk factors for disability-adjusted life-years among 10 to 24-year-olds worldwide, Gore et al. (2011) identified alcohol use as the most important one.

Across Europe, the number of adolescents admitted to hospital due to alcohol intoxication has risen in the last two decades (Slovak Republic: Kuzelova et al., 2009; Croatia: Bitunjac & Saraga, 2009; Netherlands: Bouthoorn et al., 2011). For example, in 2013, 23,267 ten to nineteen-year-olds in Germany were treated in hospital because of alcohol intoxication (Federal Statistical Office, 2015), which represents an increase of more than 40% compared to the year 2004. This is particularly worrying as alcohol intoxication can lead to hypoglycemia, hypothermia, injuries and coma (Lamminpää, 1995). Furthermore, risky drinking in adolescence is correlated with poor academic performance, unplanned pregnancy, violence and accidents (Gmel et al., 2003).

Adolescents brought to hospital emergency rooms can be considered as a ‘window of opportunity’ for delivering interventions aimed at counteracting alcohol intoxication. Adolescents and young adults with problematic alcohol use reported reduced alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related problems after participating in a motivational interviewing (MI) intervention compared to standard care, which consisted, for example, of general medical practice or the provision of handouts or brief feedback (Spirito et al., 2004, Monti et al., 1999, Monti et al., 2007, Bernstein et al., 2010).

The most widely implemented emergency room intervention in Germany targeting adolescents' acute alcohol intoxication is “HaLT” (Hart am Limit; Villa Schöpflin, 2009). In addition to standard medical care, HaLT consists of a psychosocial intervention on the morning after admission usually conducted by a social worker and includes motivational interviewing strategies (Rollnick & Miller, 1995) to enhance adolescents' commitment to cutting down risky alcohol use. In addition, information on the effects of alcohol is given and the previous day's events which led to this severe intoxication are discussed (Stolle et al., 2009, Stürmer and Wolstein, 2011). Adolescents are also invited to participate in a group intervention, where they can discuss their drinking motives within the setting of outdoor activities (Villa Schöpflin, 2009). Adolescents who participated in this group intervention showed better results with regard to episodic heavy drinking than the non-participating group (Wurdak et al., 2014).

Up to now, the HaLT intervention did not account for drinking motives. This is particularly regrettable since the factors proximate to drinking, such as motives, are not only thought to be more easily accessible for prevention efforts than distal factors, but also tend to reflect or include such distal factors as culture, situation or personality (Cox and Klinger, 1988, Cox and Klinger, 1990, Kuntsche et al., 2006a). Drinking motives are the final pathway to alcohol use, the gateway through which more distal influences, such as personality characteristics or cultural differences, are mediated (Kuntsche et al., 2008, Kuntsche et al., 2015).

According to the Motivational Model of Alcohol Use (Cox and Klinger, 1988, Cox and Klinger, 1990), drinking motives can be classified by crossing two dimensions (source: internal or external and kind of reinforcement: positive or negative) to obtain four different categories: enhancement, social, coping and conformity motives (Cooper, 1994; see Table 1 for item examples). High scores in enhancement motives are associated with heavy drinking (Cooper, 1994, Kuntsche et al., 2014, Wurdak et al., 2010) and coping motives are also linked to alcohol-related problems (Cooper, 1994, Kuntsche et al., 2005).

Table 1.

Classification of drinking motives according to the kind of reinforcement (positive or negative) and source (internal or external).

| Positive | Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Enhancement motives, e.g. “because it's fun” |

Coping motives, e.g.“to forget about your problems” |

| External | Social motives, e.g.“because it helps you enjoy a party” | Conformity motives, e.g. “so you won’t feel left out” |

Kuntsche and Gmel, (2004), Kuntsche et al., 2005, Kuntsche et al., 2006b, Kuntsche et al., 2010b and Kuntsche and Labhart (2013b) therefore describe two different risk groups that basically differ in terms of positive and negative reinforcement (cf. Table 1). Enhancement drinkers tend to enjoy the feeling of drunkenness and their motives often appear in conjunction with personality traits such as extraversion, impulsivity or sensation-seeking (internal positive reinforcement). Additionally, they often drink with their peers and thus score high on social motives (external positive reinforcement). Coping drinkers tend to be introvert and anxious and consume alcohol on their own to forget about their worries and problems (internal negative reinforcement). Furthermore, they tend to drink to be liked or accepted by others or gain access to peer groups and thus score high on conformity motives (external negative reinforcement).

One-size-fits-all interventions do not take into account the particular needs of these two groups. Experts point out that “it might be more effective if enhancement and coping drinkers were targeted by distinct prevention programs that take into account their specific needs and problems” (Kuntsche & Cooper, 2010a, p. 52). For example, coping drinkers in particular are thought to benefit from stress relaxation techniques as they drink to forget about their problems and to reduce their stress levels.

However, to our knowledge, drinking motives have not yet been considered in psychosocial interventions within the setting of emergency rooms. Conrod et al., 2006, Conrod et al., 2011 tested personality-targeted interventions in order to reduce alcohol consumption among adolescents, but drinking motives were addressed only indirectly and the intervention appears unsuitable for implementation in an emergency-room setting since it is a time-consuming process consisting of two 90-minute group sessions.

When developing and testing motive-tailored interventions, it is important to take gender differences into account as boys score higher on enhancement motives, whereas coping drinkers tend to be female (Kuntsche et al., 2006a, Kuntsche et al., 2006b) and as the prevalence of alcohol consumption and binge drinking is higher among boys (Kraus et al., 2011).

The aim of this study is to develop drinking-motive-tailored interventions for alcohol-intoxicated adolescents and to test whether participants receiving a motive-tailored intervention show a greater reduction in alcohol consumption compared to the HaLT psychosocial intervention applied in general (i.e. a non-motive-tailored intervention).

Methods

Study design

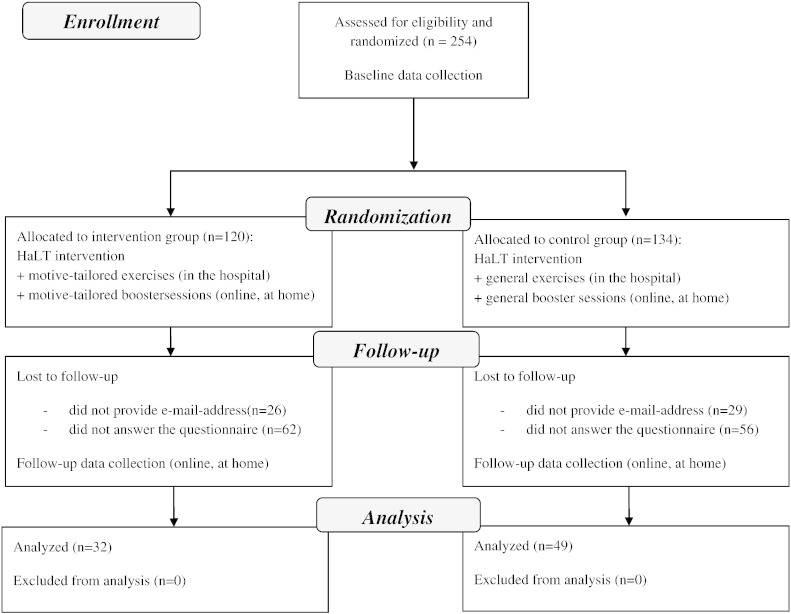

In a randomized controlled trial (see Fig. 1, drawn up in accordance with the CONSORT Statement: www.consort-statement.org), adolescents who were admitted to hospital between December 2011 and May 2012 in one of the six largest HaLT centers in Bavaria (Augsburg, Bamberg, Erlangen, Munich, Nuremberg and Schweinfurt) and at two large HaLT centers in two other federal states of Germany (Hanover in Lower Saxony and Leipzig in Saxony) were randomly assigned either to the motive-tailored HaLT intervention group (IG) or to the standard HaLT intervention, here regarded as the control group (CG).

Fig. 1.

Study procedure.

Sample size was determined with the software G*Power 3 (http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3/). With alpha = 5%, power = 80% and effect size = 0.35 a sample size of n = 204 was calculated. The original sample consisted of 254 adolescents, randomized into those who received motive-tailored HaLT interventions (IG; n = 120) and those who were given general (CG; n = 134) HaLT interventions. The simple randomization into these two groups was conducted via a RANDOM algorithm on the tablet PC. Thereof, 199 adolescents (78.3%) provided their e-mail-address and were invited to visit the website, complete booster sessions and fill out the follow-up questionnaire. From this sample, we obtained 81 follow-up questionnaires, equating to a response rate of 40.7% (i.e. 31.9% of the original sample). This final analytic sample did not differ from the non-response sample in terms of age (t = − 0.789, p = 0.431) and gender (Chi2 = 0.014, p = 0.904). Furthermore, there were no significant differences regarding drinking frequency (t = 0.017, p = 0.986), frequency of binge drinking (t = 0.911, p = 0.363) and drunkenness days (t = 1.960, p = 0.05). Adolescents in the analytic sample differed from the non-response sample in terms of the type of schooling (Chi2 = 13.469, p < 0.05; participants with lower educational levels are underrepresented in the final sample).

Data collection took place in the hospital just before the intervention started (baseline, t1) and four weeks later via an online questionnaire (follow-up, t2). Adolescents had to give their informed consent to take part in the study. Participants received an online voucher (amazon.de) worth 15 euros for completing the follow-up questionnaire. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the University of Bamberg and registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS ID: DRKS00005588).

Procedure

To be able to specifically target the intervention, combinations of motives were used to account for the two risk groups with internal positive or negative reinforcement (enhancement or coping motives), which are further specified according to the score for external positive or negative reinforcement (social or coping motives). Consequently, adolescents were classified into six groups: ‘pure’ enhancement drinkers (low social motives), ‘pure’ coping drinkers (low conformity motives), drinkers with enhancement and social motives, drinkers with coping and conformity motives, drinkers scoring high on both enhancement and coping motives, and those scoring low on these motives. This classification took place after randomization. Based on the participant's answers in the drinking motive questionnaire revised short form (DMQ-R SF; Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009), we developed a classification algorithm for allocating the participants to one of the six groups. The classification algorithm was based on a comparison of the means and z-values of the DMQ-R answers. e.g., to be classified as an enhancement and coping drinker, the mean score on enhancement motives had to be the same as the mean score on coping motives and both z-values needed to be positive (further information on the algorithm can be obtained from the authors on request).

Based on this classification and in addition to the HaLT intervention, adolescents from the IG were offered a set of different motive-tailored exercises designed to provide alternative ways of fulfilling the specific needs of the six motive groups. For example, enhancement and social drinkers received exercises relating to alternative ways of spending their leisure time, sensation-seeking activities and dealing with peer pressure. Coping drinkers were shown ways of dealing with problems and stress and introduced to various relaxation methods. Likewise, as an add-on to the HaLT psychosocial intervention, participants from the CG received exercises with alcohol-related information in general, for example on legal drinking age or the effects of alcohol intoxication and first aid activities.

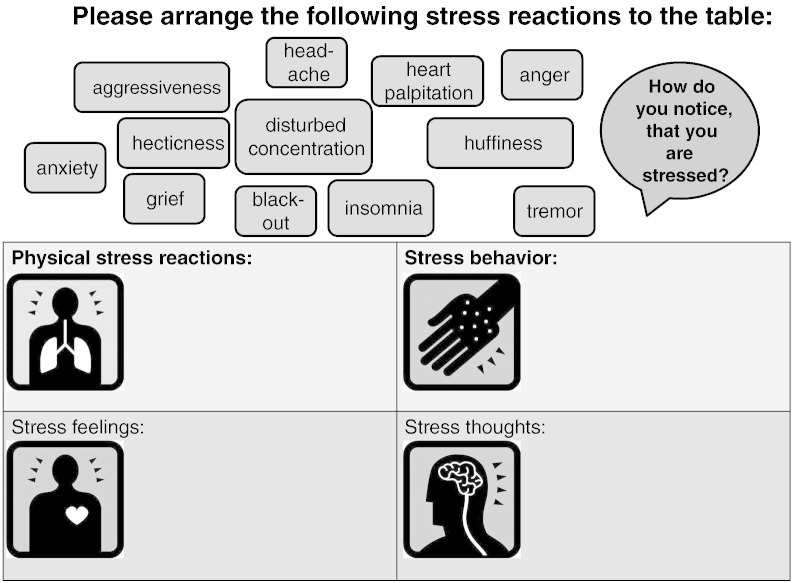

We developed 27 different exercises, each taking about ten minutes to complete. The exercises were based on evaluated treatment programs or psychological theories on, for instance, interpersonal skills (e.g. Hinsch and Pfingsten, 2007), protective behavioral strategies (LaBrie et al., 2011) and dealing with stress (Lohaus et al., 2007). For example, exercises in stress reduction for coping drinkers refer to the evaluated training program for adolescents developed by Beyer and Lohaus, 2005, Beyer and Lohaus, 2006, which is based on problem-solving competencies (cf. Fig. 2 for an example). All exercises contained educational information as well as interactive sections. Video clips, audio files, pictures or quotes from celebrities were included to catch the adolescents' attention and to make the exercises more attractive. All adolescents were asked to complete booster sessions at home (motive-tailored in the IG and general in the CG). Both groups completed exercises on tablet PCs (at the hospital) and via the Internet (at home), thus balancing out any potential bias from the use of modern communication devices.

Fig. 2.

Example of an exercise designed for coping drinkers to reduce stress (excerpt).

Social workers who conducted the intervention received a training session and a detailed manual including information on the theoretical background, instructions on how to use the tablet PCs and explanations of the data collection procedure and the different exercises. Adolescents completed the baseline questionnaire and one exercise (motive-tailored in the IG, general in the CG) on the tablet PC as part of the HaLT psychosocial intervention on the morning after their admission. Booster sessions were provided on the website and participants were asked to complete these at home. Participants who filled out the follow-up questionnaire visited the website on average three times (median = 3.0) in the four-week period and spent approximately 28 min (median = 25.0) there. Participants from the IG reported that they visited the website more often (M = 3.65, SD = 4.94) and spent more time (M = 32.19, SD = 32.17) on the exercises than CG adolescents (frequency: M = 2.60, SD = 1.94; time: M = 24.77, SD = 17.10), but these differences were not statistically significant (frequency: t = 1.31, p = 0.193; time: t = 1.18, p = 0.244).

Measures

Sociodemographics

Age and gender were included at baseline.

Drinking motives

The 12 items (three per motive category) of the DMQ-R SF (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009) measure the relative frequency of drinking due to enhancement, social, coping and conformity motives (see Table 1 for item examples) within the past 30 days on a five-point scale from 1 = never to 5 = always. Its validity and reliability have been demonstrated in a variety of studies across Europe (Németh et al., 2011, Mazzardis et al., 2010, Kuntsche et al., 2014, Kuntsche et al., 2015). Internal consistencies (Cronbach's Alpha) were .81, .85, .88 and .88 for enhancement, social, coping and conformity motives, respectively.

Alcohol consumption

Questions were adapted from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD; Hibell et al., 2009, Kraus et al., 2008), requested numerical responses (0–30) and included frequency of alcohol consumption (During the last 30 days: On how many days have you had any alcoholic beverage to drink, e.g. beer, wine/sparkling wine, mixed drinks, alcopops or spirits?), frequency of binge drinking (During the last 30 days: On how many days have you had five or more alcoholic drinks, e.g. beer, wine/sparkling wine, mixed drinks, alcopops or spirits?) and frequency of drunkenness (During the last 30 days: On how many occasions (if any) have you been intoxicated from drinking alcoholic beverages so that you e.g. staggered when walking, were not able to speak properly, or could not remember anything the next day?).

Statistical analyses

Following the recommendation of Armijo-Olivo et al. (2009), we did not conduct intention-to-treat analyses as “interpretation of the ITT analysis is difficult if (…) the proportion of patients who drop out is significant. ITT is inappropriate for efficacy researchers and clinicians since it analyses the effect of treatment prescribed and not the effect of treatment received“(Armijo-Olivo et al., 2009, p. 41). For these reasons we performed an available case analysis.

To test whether the motive-tailored intervention resulted in a greater reduction in alcohol consumption compared to the standard HaLT intervention plus general exercises, we used ANOVAs with repeated measurements. Unfortunately, comparative statistical tests rarely yield significant results when using small samples, which is usually the case when dealing with adolescents admitted to hospital due to acute alcohol intoxication (Monti et al., 1999, Spirito et al., 2004). We therefore also calculated the proportional reduction in alcohol consumption from baseline to follow-up and the corresponding effect sizes (Cohen's d) according to the formula for different variances but same sample sizes (Bortz & Döring, 2006). Cohen's d values of 0.8, 0.5 and 0.2 represent large, medium and small effects, respectively (Bortz & Döring, 2006). Effect sizes like Cohen's d are regarded as particularly suitable for assessing the practical relevance of interventions (Kessler, 2015). Due to gender differences regarding alcohol consumption and drinking motives (Holmila and Raitasalo, 2004, Kuntsche et al., 2006b, Kuntsche et al., 2006c, Kuntsche and Kuntsche, 2009, Kraus et al., 2011), all analyses were conducted separately for each gender.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The randomization was successful since the IG and the CG from the final sample did not differ in terms of age (t = − 0.328, p = 0.744), gender (x2 = 0.521, p = 0.470), type of schooling (x2 = 3.482, p = 0.323), baseline frequency of alcohol consumption (t = 0.982, p = 0.329), binge drinking (t = 0.788, p = 0.433) and drunkenness (t = − 0.069, p = 0.945). At baseline, adolescents had consumed alcohol on 2.72 and 3.43 days on average in the last 30 days in the IG and CG, respectively. They reported binge drinking on 1.19 (IG) and 1.49 (CG) days and drunkenness on 1.03 (IG) and 1.02 (CG) days.

Intervention effectiveness

Among girls, the interaction between time (baseline, t1 vs. follow-up, t2) and group (CG vs. IG) was significant for frequency of alcohol consumption and binge drinking (Table 2). There was no significant interaction in relation to the frequency of drunkenness. The proportional reductions and corresponding effect sizes showed no effect, a small effect and a large effect for the frequency of alcohol consumption, drunkenness and binge drinking, respectively, in the CG. In the IG, however, the effect sizes for each of the alcohol consumption measures were even much higher than the .8 threshold for large effects (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Alcohol consumption among girls — comparison of intervention and control group.

| Girls | Group | t1/t2 | N | M | SD | Time ∗ group interaction |

Proportional change | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ||||||||

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | CG | t1 | 19 | 2.16 | 2.141 | 7.770 | 0.009 | + 7% | + 0.06 |

| t2 | 19 | 2.32 | 3.092 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 15 | 2.33 | 1.839 | − 77% | − 1.18 | |||

| t2 | 15 | 0.53 | 1.125 | ||||||

| Frequency of binge drinking | CG | t1 | 19 | 0.58 | 0.507 | 7.005 | 0.013 | − 64% | − 0.80 |

| t2 | 19 | 0.21 | 0.419 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 15 | 1.13 | 0.990 | − 100% | − 1.61 | |||

| t2 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.000 | ||||||

| Frequency of drunkenness | CG | t1 | 19 | 0.79 | 0.419 | 1.414 | 0.243 | − 33% | − 0.20 |

| t2 | 19 | 0.53 | 1.837 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 15 | 0.93 | 0.458 | − 100% | − 2.87 | |||

| t2 | 15 | 0.00 | 0.000 | ||||||

Among boys, there was no significant effect for any of the alcohol consumption measures (Table 3). In both the CG and IG, there were small and large effects for the frequency of alcohol consumption and drunkenness, respectively. For the frequency of binge drinking, the effect size was just above the threshold for medium effects in the CG and just below it in the IG.

Table 3.

Alcohol consumption among boys – comparison of intervention and control group

| Boys | Group | t1/t2 | N | M | SD | Time ∗ group interaction |

Proportional change | Cohen's d | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | ||||||||

| Frequency of alcohol consumption | CG | t1 | 30 | 4.23 | 4.321 | 0.310 | 0.581 | − 39% | − 0.44 |

| t2 | 30 | 2.60 | 2.931 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 17 | 3.06 | 2.135 | − 27% | − 0.36 | |||

| t2 | 17 | 2.24 | 2.412 | ||||||

| Frequency of binge drinking | CG | t1 | 30 | 2.07 | 2.392 | 2.150 | 0.150 | − 60% | − 0.57 |

| t2 | 30 | 0.83 | 1.895 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 17 | 1.24 | 0.970 | − 39% | − 0.43 | |||

| t2 | 17 | 0.76 | 1.251 | ||||||

| Frequency of drunkenness | CG | t1 | 30 | 1.17 | 0.950 | 0.000 | 0.988 | − 79% | − 1.04 |

| t2 | 29 | 0.24 | 0.830 | ||||||

| IG | t1 | 17 | 1.12 | 0.485 | − 83% | − 2.09 | |||

| t2 | 16 | 0.19 | 0.403 | ||||||

Discussion

The aim of this study was to develop and test the effectiveness of a drinking-motive-tailored intervention for alcohol-intoxicated adolescents admitted to hospital emergency rooms. The results showed a reduction in most alcohol consumption measures among girls and boys in both the CG and IG. It appears that the experience of a hospitalization due to acute alcohol intoxication together with a psychosocial intervention already prevents risky drinking behaviors four weeks later.

Over and above this general effect, girls who received a motive-tailored psychosocial intervention reported a lower drinking frequency and less binge drinking at follow-up than girls who received a non-motive-tailored psychosocial intervention. The additional effect of the motive-tailored intervention among girls is especially remarkable as both the CG and IG are comparable in terms of socio-demographics, drinking behavior at baseline, the experience of hospital admission due to intoxication and receiving a psychosocial intervention and additional exercises via tablet PCs and the Internet. The only difference is the motive-tailored vs. the general content of the exercises. It appears that tailoring the exercises to the individuals’ personal drinking motives and providing specific advice for their needs and problems was more efficient in helping them to abstain from drinking or reduce their drinking frequency and binge drinking in the weeks after the hospital admission.

For boys, in contrast, there was no such difference. They also reduced their alcohol consumption at follow-up but this was independent of whether they received a motive-tailored or non-motive-tailored intervention. One explanation may be that girls, who are generally more conscientious than boys (Freudenthaler et al., 2008, Schmitt et al., 2009), completed the exercises more conscientiously and therefore benefited more from the specificity of the content. Another reason may be that the alcohol consumption of girls is more affected by internal factors such as motives whereas that of boys is more affected by external factors such as characteristics of the social surroundings when drinking (Koordeman et al., 2011, Thrul and Kuntsche, 2015).

Among the limitations of the study is the high non-response rate. The hospital experience is usually unpleasant since participants feel physically unwell due to the consequences of alcohol intoxication, may be ashamed about the event and probably do not wish to recapitulate the details of this potentially traumatic experience. These may be reasons for not completing the follow-up questionnaire weeks later, thus resulting in a high non-response rate. Fortunately, the analytic sample and the non-response sample were comparable in terms of age, gender and frequency of alcohol consumption and binge drinking. However, we have to consider a possible selection bias of adolescents with a stronger commitment or higher motivation which violates randomization and might limit the generalizability of our results. Another limitation is the rather short follow-up period of four weeks (which we chose so as not to further increase the non-response rate). However, future research should aim to use longer follow-up periods by making further efforts to minimize attrition. Among the study’s strengths is the rather high initial sample size taking into account the small percentage of adolescents who are treated in hospital due to alcohol intoxication (e.g. 0.22% of all 10 to 20-year-olds were admitted to hospital due to alcohol intoxication in the federal state of Bavaria in 2009; Wurdak et al., 2013). Another strength is the multi-site character of the study, it having included multiple hospitals from different regions in Germany. It thus appears likely that the reported results apply to a large proportion of adolescents treated for acute intoxication in Germany.

Conclusion

Whereas participants generally reduced their alcohol consumption in the four weeks following hospitalization due to acute alcohol intoxication and participation in a psychosocial intervention, among girls, the reduction was more pronounced when the intervention was conducted in accordance with their needs as determined by their drinking motives expressed at baseline compared to the non-motive-tailored intervention. Since this effect was not observed in boys, further research should investigate ways to better tailor this intervention to the needs of boys admitted to hospital due to acute alcohol intoxication.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest. Financial support for conducting this study was provided by the Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (Federal Ministry of Health) (IIA5-2511DSM213) and the University of Bamberg. The authors are not in receipt of funding from the alcohol industry.

Transparency document

Transparency document.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Thomas Musgrove for English copy editing, Andreas Schubert for programming the website, the team of the University of Bamberg, the Bayerische Akademie für Sucht- und Gesundheitsfragen, the HaLT centers and above all the participants.

Footnotes

The Transparency document associated with this article can be found in the online version.

Contributor Information

Mara Wurdak, Email: mara.wurdak@uni-bamberg.de.

Jörg Wolstein, Email: joerg.wolstein@uni-bamberg.de.

Emmanuel Kuntsche, Email: ekuntsche@suchtschweiz.ch.

References

- Armijo-Olivo S., Warren S., Magee D. Intention to treat analysis, compliance and how to deal with missing data in clinical research: a review. Phys. Ther. Rev. 2009;14:36–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein J., Heeren T., Edward E. A brief motivational interview in a pediatric emergency department, plus 10-day telephone follow-up, increases attempts to quit drinking among youth and young adults who screen positive for problematic drinking. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2010;17:890–902. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2010.00818.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A., Lohaus A. Stressbewältigung im Jugendalter: Entwicklung und Evaluation eines Präventionsprogrammes. Psychol. Erzieh. Unterr. 2005;52:33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A., Lohaus A. Hogrefe; Göttingen: 2006. Stressbewältigung im Jugendalter – Ein Trainingsprogramm. [Google Scholar]

- Bitunjac K., Saraga M. Alcohol Intoxication in pediatric age: ten-year retrospective study. Clin. Sci. 2009 doi: 10.3325/cmj.2009.50.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortz J., Döring N. Springer Medizin Verlag; Heidelberg: 2006. Forschungsmethoden und Evaluation für Human- und Sozialwissenschaftler (4. Auflage) [Google Scholar]

- Bouthoorn S.H., van Hoof J.J., van der Lely N. Adolescent alcohol intoxication in Dutch hospital centers of pediatrics: characteristics and gender differences. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00431-011-1394-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod P.J., Stewart S.H., Comeau N., Maclean A.M. Efficacy of cognitive–behavioral interventions targeting personality risk factors for youth alcohol misuse. J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2006;35:550–563. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrod P., Castellanos-Ryan N., Mackie C. Long-term effects of a personality-targeted intervention to reduce alcohol use in adolescents. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2011;79:296–306. doi: 10.1037/a0022997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper M.L. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychol. Assess. 1994;6:117–128. [Google Scholar]

- Cox W.M., Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1988;97:168–180. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.97.2.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox W.M., Klinger E. Incentive motivation, affective change, and alcohol use: a model. In: Cox W.M., editor. Why People Drink. Gardner Press; New York: 1990. pp. 291–314. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Statistical Office [Statistisches Bundesamt Deutschland] Statistisches Bundesamt; Wiesbaden: 2015. Gesundheit – Diagnosedaten der Patienten und Patientinnen in Krankenhäusern (einschl. Sterbe- und Stundenfälle). Fachserie 12, Reihe 6.2.1. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenthaler H.H., Spinath B., Neubauer A.C. Predicting school achievement in boys and girls. Eur. J. Personal. 2008;22:231–245. [Google Scholar]

- Gmel G., Rehm J., Kuntsche E. Binge drinking in Europe: definitions, epidemiology, and consequences. Sucht. 2003;2:105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gore F.M., Bloem P.J.N., Patton G.C. Global burden of disease in young people aged 10-24 years: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2011 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60512-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibell B., Guttormsson U., Ahlström S. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and other Drugs (CAN); Stockholm: 2009. The 2007 ESPAD Report — Substance Use Among Students in 35 European Countries. [Google Scholar]

- Hinsch R., Pfingsten U. Weinheim; Beltz Verlag: 2007. Gruppentraining sozialer Kompetenzen — GSK. [Google Scholar]

- Holmila M., Raitasalo K. Gender differences in drinking: why do they still exist? Addiction. 2004;100:1763–1769. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01249.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler H. Thieme; Stuttgart: 2015. Kurzlehrbuch Medizinische Psychologie und Soziologie. [Google Scholar]

- Koordeman R., Kuntsche E., Anschutz D.J., van Baaren R.B., Engels R.C.M.E. Cognitive aspects — do we act upon what we see? Direct effects of alcohol cues in movies on young adults' alcohol drinking. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:393–398. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus L., Papst A., Steiner S. IFT Institut für Therapieforschung; München: 2008. Europäische Schülerstudie zu Alkohol und anderen Drogen 2007 (ESPAD) - Befragung von Schülerinnen und Schülern der 9. und 10. Klasse in Bayern, Berlin, Brandenburg, Hessen, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Saarland und Thüringen. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus L., Papst A., Piontek D. IFT Institut für Therapieforschung; München: 2011. Europäische Schülerstudie zu Alkohol und anderen Drogen 2011 (ESPAD) - Befragung von Schülerinnen und Schülern der 9. und 10. Klasse in Bayern, Berlin, Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern und Thüringen. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Cooper M.L. Drinking to have fun and to get drunk: motives as predictors of weekend drinking over and above usual drinking habits. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110:259–262. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Gmel G. Emotional wellbeing and violence among social and solitary risky single occasion drinkers in adolescence. Addiction. 2004;99:331–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Kuntsche S. Development and Validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ-R SF) J. Clin. Child Adolesc. Psychol. 2009;38:899–908. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Labhart F. Drinking motives moderate the impact of pre-drinking on heavy drinking on a given evening and related adverse consequences — an event-level study. Addiction. 2013;108:1747–1755. doi: 10.1111/add.12253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Knibbe R., Gmel G., Engels R. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2005;25:841–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Knibbe R., Gmel G., Engels R. Replication and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised (DMQ-R, Cooper, 1994) among adolescents in Switzerland. Eur. Addict. Res. 2006;12:161–168. doi: 10.1159/000092118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Knibbe R., Gmel G., Engels R. Who drinks and why? A review of socio-demographic, personality and contextual issues behind the drinking motives in young people. Addict. Behav. 2006;31:1844–1857. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Gmel G., Wicki M., Rehm J., Grichting E. Disentangling gender and age effects of risky single occasion drinking during adolescence. Eur. J. Pub. Health. 2006;16:670–675. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., von Fischer M., Gmel G. Personality factors and alcohol use: a mediator analysis of drinking motives. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2008;45:796–800. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Knibbe R., Engels R., Gmel G. Being drunk to have fun or to forget problems? Identifying enhancement and coping drinkers among risky drinking adolescents. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2010;26:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Nic Gabhainn S., Roberts C. Drinking motives and links to alcohol use in 13 European countries. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:428–437. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2014.75.428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E., Wicki M., Windlin B. Drinking motives mediate cultural differences but not gender differences in adolescent alcohol use. J. Adolesc. Health. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuzelova M., Hararova A., Ondriasova E. Alcohol intoxication requiring hospital admission in children and adolescents: retrospective analysis at the University Children's Hospital in the Slovak Republic. Clin. Toxicol. 2009;47:556–561. doi: 10.1080/15563650903018611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaBrie J.W., Lac A., Kenney S.R., Mirza T. Protective behavioral strategies mediate the effect of drinking motives on alcohol use among heavy drinking college students: gender and race differences. Addict. Behav. 2011;36:354–361. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamminpää A. Alcohol intoxication in childhood and adolescence. Alcohol Alcohol. 1995;30:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohaus A., Domsch H., Fridrici M. Springer; Heidelberg: 2007. Stressbewältigung für Kinder und Jugendliche. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzardis S., Vieno A., Kuntsche E., Santinello M. Italian validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ-R SF) Addict. Behav. 2010;30:305-209. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P.M., Colby S.M., Barnett N.P. Brief Intervention for harm reduction with alcohol-positive older adolescents in a hospital emergency department. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1999;67:989–994. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.6.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti P.M., Barnett N.P., Colby S.M. Motivational interviewing versus feedback only in emergency care for young adult problem drinking. Addiction. 2007;102:1234–1243. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Németh Z., Urbán R., Kuntsche E. Drinking motives among Spanish and Hungarian young adults — a cross-national study. Alcohol Alcohol. 2011;46:261–269. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agr019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J., Taylor B., Room R. Global burden of disease from alcohol, illicit drugs and tobacco. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2006;25:503–513. doi: 10.1080/09595230600944453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollnick S., Miller W.R. What is motivational interviewing? Behav. Cogn. Psychother. 1995;23:325–334. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt D.P., Realo A., Voracek M., Allik J. Why can't a man be more like a woman? Sex differences in Big Five personality traits across 55 cultures. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2009;94 doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.94.1.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schöpflin V. Alkoholprävention bei Kindern und Jugendlichen (3. Auflage) Villa Schöpflin – Zentrum für Suchtprävention gGmbH. Verfügbar unter; Lörrach: 2009. Handbuch Trainer-Manual und Projektdokumentation. ( http://www.halt-projekt.de/images/stories/pdf/handbuch_halt_2009.pdf (accessed 29th May 2015)) [Google Scholar]

- Spirito A., Monti P.M., Barnett N.P. A randomized clinical trial of a brief motivational intervention for alcohol-positive adolescents treated in an emergency department. J. Pediatr. 2004;145:396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.04.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolle M., Sack P.-M., Thomasius R. Binge drinking in childhood and adolescence. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2009;106:323–328. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2009.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stürmer M., Wolstein J. Rauschtrinken bei Kindern und Jugendlichen – Indizierte Prävention in der Akutsituation im Krankenhaus. Kinderarztl. Prax. 2011;82:160–165. [Google Scholar]

- Thrul J., Kuntsche E. The impact of friends on young adults' drinking over the course of the evening — an event-level analysis. Addiction. 2015 doi: 10.1111/add.12862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurdak M., Dörfler T., Eberhard M., Wolstein J. Tagebuchstudie zu Trinkmotiven, Affektivität und Alkoholkonsum bei Jugendlichen. Sucht. 2010;56:175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Wurdak M., Ihle K., Stürmer M. Indicators for measuring the extent of binge drinking among adolescents in Bavaria (Indikatoren für das Ausmaß jugendlichen Rauschtrinkens in Bayern) Sucht. 2013;59:225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Wurdak M., Kuntsche E., Kraus L., Wolstein J. Effectiveness of a brief intervention with and without booster session for adolescents hospitalized due to alcohol intoxication. J. Subst. Use. 2014 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Transparency document.