Abstract

Background

The poor health consequences of stress are well recognized, and students in higher education may be at particular risk. Tai Chi integrates physical exercise with mindfulness techniques and seems well suited to relieve stress and related conditions.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of the health benefits of Tai Chi for students in higher education reported in the English and Chinese literature, using an evidence hierarchy approach, allowing the inclusion of studies additional to randomized controlled trials.

Results

Sixty eight reports in Chinese and 8 in English were included — a combined study sample of 9263 participants. Eighty one health outcomes were extracted from reports, and assigned evidence scores according to the evidence hierarchy. Four primary and eight secondary outcomes were found. Tai Chi is likely to benefit participants by increasing flexibility, reducing symptoms of depression, decreasing anxiety, and improving interpersonal sensitivity (primary outcomes). Secondary outcomes include improved lung capacity, balance, 800/1000m run time, quality of sleep, symptoms of compulsion, somatization and phobia, and decreased hostility.

Conclusions

Our results show Tai Chi yields psychological and physical benefits, and should be considered by higher education institutions as a possible means to promote the physical and psychological well-being of their students.

Keywords: Tai Chi, Graduate student, Stress, Well-being, Physical, Mental

Highlights

-

•

We reviewed the benefits of Tai Chi in 9263 tertiary students from 76 studies.

-

•

Tai Chi is likely to yield psychological and physical benefits for tertiary students.

-

•

Physical benefits include improved flexibility, lung capacity and balance.

-

•

Psychological benefits include reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety.

-

•

Education institutions should consider such benefits for the well-being of students.

Introduction

Excess stress is widely recognized as a major health problem worldwide (Thoits, 2010). Chronic stress has been linked repeatedly to increased mortality, morbidity and decreased functioning of the immune system, as well as diminished cognitive function and poorer mental health (Juster et al., 2010). Students in higher education who face the pressures of a heavy workload, examinations and entrance restrictions on favored courses, such as those used in medical schools, are particularly at risk of long-term stress and the resulting higher likelihood of burnout (Dyrbye et al., 2010, Dyrbye et al., 2006, McManus et al., 2002). The prevalence and severity of many psychological conditions in students have increased over recent years, with consequences such as poor concentration and compromised productivity, which can be devastating for their productive involvement in future careers (Hunt and Eisenberg, 2010, Knight, 2013). It has also been shown that students’ physical health may deteriorate, with some students exercising and sleeping less once they begin studying (Wolf and Kissling, 1984).

A large body of research has investigated how students may react to stressors (Alzahem et al., 2011, Zhang and Goodson, 2011). Maladaptive ways of coping with stress include excessive alcohol use (Park and Levenson, 2002) and unhealthy eating habits (Wichianson et al., 2009), as well as denial and avoidance (Maclean et al., 2007), — these may provide temporary relief but exacerbate stress in the long term. In contrast, adaptive coping strategies are generally associated with positive outcomes, and include problem-focused coping and planning (Penley et al., 2002), spirituality (Kim and Seidlitz, 2002), or seeking social support (Lee et al., 2004). Various self-care strategies also play an important role, both in coping during times of stress as well as in avoiding its consequences. The teaching of skills, such as problem solving, relaxation techniques, self-management, and interpersonal skills has been frequently applied in stress-management interventions for students (Jones and Johnston, 2000, Shiralkar et al., 2013). Regular physical exercise has also been associated with psychological wellbeing (Teychenne et al., 2008), and meditation and mindfulness practices are increasingly used to promote resilience and psychological wellbeing in students (Hassed et al., 2009).

Tai Chi is an exercise system that integrates physical strengthening and self-defense with mindfulness techniques including relaxation of the mind (Tsang et al., 2008), and so may be particularly fruitful for reducing or preventing stress. It is widely accepted that the practice of Tai Chi dates back to 13th century China and has traditionally been used in various forms for the promotion and maintenance of health and longevity (Zhuo, 1982, Koh, 1981). A number of systematic reviews have attempted to investigate the often-claimed positive effects of Tai Chi on a variety of health dimensions (Adams, 2004, Kuramoto, 2006), including decreased blood pressure (Yeh et al., 2008), aerobic capacity (Lee et al., 2009), psychosocial wellbeing (Wang et al., 2009), and psychological wellbeing (Wang et al., 2010). The general findings of these reviews point toward potential health benefits, although a lack of sufficient high-quality studies often prevents strong conclusions.

The purpose of the present systematic review was to survey the academic literature on the health benefits of Tai Chi in relation to students in higher education. Purposively selecting a potentially at-risk population may reveal evidence of health benefits more clearly than a general-purpose search. In addition, given the cultural origins of Tai Chi, we deemed it appropriate to include Chinese-language studies in our review as well as English-language studies, thus substantially increasing the pool of evidence to be analyzed, which is a significant extension of previous reviews. Furthermore, evidence-based medicine involves making use of the best available evidence with which to answer our clinical questions, and this may constitute considering evidence other than that present in randomized controlled trials (Sackett et al., 1996, Mays et al., 2005). We therefore used an evidence hierarchy approach, which ranks and weights all evidence identified during our search (Jensen et al., 2004). Our aim was to identify evidence for the benefits of Tai Chi in improving the mental and physical health of students in higher education.

Methods

Two separate literature searches were conducted on 18 February 2013 to identify as many relevant publications as possible. The first of these aimed to identify material published in, or translated into, English. Online electronic searches were conducted using the seven most common databases (Google Scholar, Pubmed, CINAHL Plus, Embase, PsychInfo, Scopus, and Cochrane Library) and three library catalogues (Te Puna, World Catalogue, and University of Auckland catalogue). During this process, the researchers met as a team and search terms were extensively discussed and iteratively refined. The final search terms are shown in Table 1. The second literature search focused on articles in Chinese using four online electronic databases (Google Scholar, WangFang Data, the National Central Library of Taiwan, and China Academic Journals). This was conducted with the assistance of a fluent Chinese speaker using a subset of the search terms in Table 1 in their Chinese character forms. Hanyu pinyin forms of characters were used initially in developing the search, but were not included in the final search as their use resulted in large numbers of irrelevant hits. Our review and reporting method was guided by the Cochrane Handbook of Systematic Reviews and the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) to the extent that this was possible given our evidence hierarchy approach (Anonymous, 2015, Higgins and Green, 2011).

Table 1.

Keywords used in English-language literature search

| Set one — terms related to students | ||

|---|---|---|

| Student | College student | University student |

| Undergraduate | Postgraduate | Graduate |

| Set two – variant names of Tai Chi | ||

|---|---|---|

| Tai Chi | Taiji | |

| Set three — terms for physical and mental health | ||

|---|---|---|

| Health | Mental | Physical |

| Depression | Stress | Well-being |

| Quality of life | Anxiety | Psychological |

| Physiological | ||

Type of participants

Our participants were defined as students undertaking tertiary or higher education (Set one, Table 1). We searched the Chinese databases with the keyword 大学生 (university student), as well as in the traditional character forms.

Types of interventions

Our intervention was defined as any form of Tai Chi (Set two, Table 1). Papers concerning “Qigong”, “mindfulness” and other activities related to, but not constituting Tai Chi, were excluded. In the Chinese database searches we used the keyword 太极拳 (taijiquan), as well as in the traditional character forms.

Types of outcome measures

Our outcome measures were defined as any reported physical or mental health effects of Tai Chi practice, both beneficial and potentially deleterious (Set three, Table 1). The keyword 健康 (health), as well as the traditional character forms, were used for the Chinese database search.

For the Cochrane and PsychInfo databases, only keywords from the first two sets were used due to the smaller number of articles returned (Table 1). Truncation, word variants and MESH terms were also used in searches, which increased the number of relevant papers found.

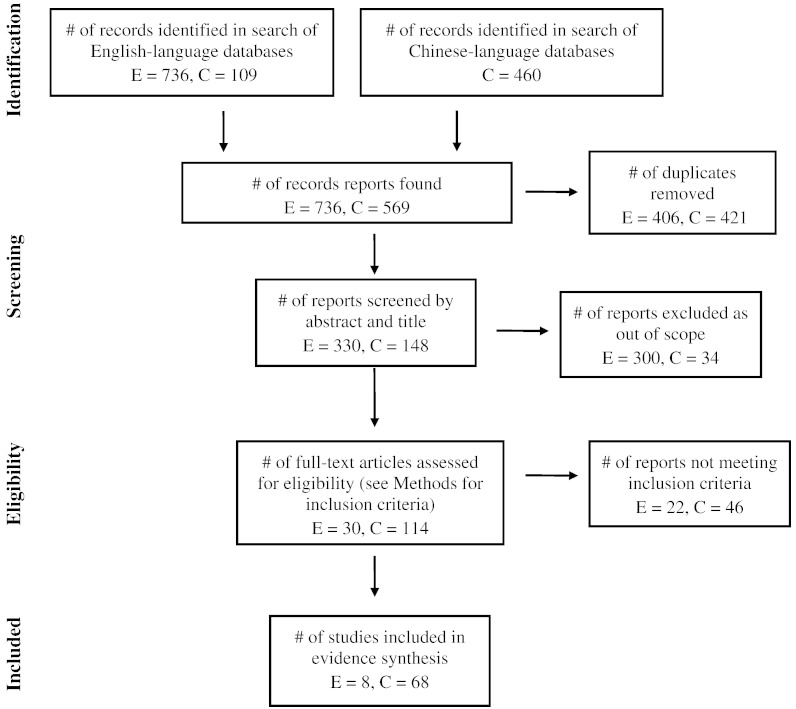

Published theses from the grey literature were also searched and included, but unpublished literature was not sourced. Reference lists of publications were not screened for further possible studies. All search results were imported into a reference management program (Refworks, Bethesda, USA) to form a single library of references. Duplicates were then removed. The titles and abstracts of remaining articles were screened, and the full texts were retrieved for those papers that the authors agreed were relevant to the research aim. The final set of papers included in our review was determined based on their full texts and the following inclusion criteria (see Fig. 1 for a flow diagram of the full screening process):

-

1.

The paper or report must have been published in the 10 years, 2003–2012 inclusive (a period coinciding with an increased number of publications on Tai Chi (Adams, 2004)), and the full texts of papers must be available in English or Chinese.

-

2.

The paper or report must be original: an experimental research paper, review or report published in the peer reviewed literature, or a research thesis. Essays and narrative articles not published in the peer-reviewed literature or that merely mention or discuss the findings of other studies were excluded.

-

3.

There must be a specific discussion of students in higher education at least once in the paper. If a paper is an experimental study, students must form at least one of the intervention groups.

-

4.

The intervention used must be a form of Tai Chi. The use of Tai Chi must not be combined with any other intervention in such a way that the effects of the Tai Chi aspect cannot be isolated.

-

5.

The outcomes included were those of any form of health-related effect reported in the study.

Fig. 1.

Combined flow diagram for Chinese and English database searches*

*Number of reports: E = English, C = Chinese.

Individual reports were then given an evidence score based on their methodological strength, while discounting multiple reports from the same first author, according to a hierarchy of evidence developed by Jensen and colleagues (Table 2) (Jensen et al., 2004). This scoring strategy was used because, unlike other systematic reviews, it allows the inclusion and weighting of evidence from studies which are not randomized-controlled trials — this was particularly important in our present study as we wanted to include more traditional forms of knowledge on Tai Chi. Furthermore, Tai Chi is most often reported as an intervention in the literature, and so the evidence hierarchy approach allows the weighing-up of the evidence for the benefit of these various types of interventions. Individual reports were independently scored by two study investigators (AYL and CSW) who conferred to arrive at the final score where discrepancies occurred.

Table 2.

Levels of evidence and scoring regime.

| Level of evidence | Combined number of participants in included studies (n = 9263) | No. of studies (n = 76)* | Scoring regime for each publication** |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ia — evidence from meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials | 0 | E = 0 C = 0 |

Evidence levels Ia-III X = 8; Y = 4; Z = 2 |

| Ib — evidence from at least one randomized control trial | 866 | E = 2 C = 10 Total = 12 |

|

| IIa— evidence from at least one controlled study without randomization | 1718 | E = 1 C = 17 Total = 18 |

|

| IIb— evidence from at least one other type of quasi-experimental study (for example one-group, pretest, posttest studies) | 2106 | E = 2 C = 17 Total = 19 |

|

| III— evidence from non-experimental descriptive studies, such as comparative studies, correlation studies and case-control studies | 4570 | E = 3 C = 21 Total = 24 |

|

| IV— evidence from expert committee reports or opinions and/ or clinical experience of respected authorities | 3† | E = 0 C = 3 Total = 3 |

Case or case series reports X = 6; Y = 3; Z = 1 Opinion reports of experts X = 4; Y = 2; Z = 0 |

*Number of reports: E = English, C = Chinese. **Highest ranking publication from each authority = X points; second highest ranking publication from that authority = Y points; each additional publication from that authority = Z points. An authority is defined as the first author of each publication or report. †Two reports at this evidence level comprise expert narration on the benefits of Tai Chi and do not include study participants.

Individual outcomes from each report were extracted and assigned the evidence score of the report from which they were drawn. These outcomes were then tabulated along with the associated reports according to whether evidence in the report supported (i.e. showed a statistically significant benefit, p < 0.05), was uncertain (i.e. did not show a significant benefit) or was dissenting of the outcome (i.e. showed a deleterious significant effect, p < 0.05). Evidence scores were reported as a total support score and a total uncertain or dissent score for each outcome (Table 3). We took a conservative approach to our analysis by requiring that evidence scores supporting an outcome must exceed the sum of both dissent and uncertain evidence scores before an outcome may be considered a possible or likely benefit of Tai Chi practice — we called this the net evidence score. Outcomes were ranked under each outcome category according to their net evidence scores (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of the benefits of Tai Chi from a systematic review of evidence⁎.

Evidence scores attached to each outcome relate to the paper from which the outcome is drawn as defined by the scheme in Table 2.

This outcome is included in The Symptom Checklist-90 (SCL-90) questionnaire, a self-reported psychometric instrument designed to evaluate a broad range of psychological problems and symptoms.

Type-A behavior is characterized by ambition, rigidity of organization, status consciousness, impatience, anxiousness and a propensity for workaholism.

Interpersonal sensitivity refers to the accuracy and/or appropriateness of perceptions, judgments, and responses we have with respect to one another.

Results

Search results

Substantially more relevant Chinese articles were found than English ones, although the English databases were larger and returned more search results (Fig. 1). The majority of Chinese studies recruited students in compulsory and optional Tai Chi courses at Chinese universities, whereas these courses are far less common outside of China. Seven hundred and thirty six articles were found in the English search — 330 remained after duplicates were removed, and 300 were excluded after screening the abstracts. After assessing full texts, 8 English-language articles were included in the final analysis. Four hundred and sixty papers were found in the Chinese search, and an additional 109 Chinese articles were included from the English search. Sixty eight Chinese reports were included in the final analysis after the exclusion process (Fig. 1).

There was a wide range in the quality of the evidence of the final 76 analyzed articles. As there were no meta-analyses of randomized control trials (level Ia), the highest level of evidence included was from Ib (evidence from at least one randomized controlled trial). The lowest level was IV (evidence from the experience of respected authorities — Table 2), and studies with a lower evidence level were excluded. The spread of levels of evidence found in English and Chinese searches were similar, with a predominance of case-control studies in both languages, and similar proportions of one-group, pre- and post-test studies and non-randomized controlled studies.

Health benefits

Consistent with the reputation of Tai Chi as a holistic health intervention, a wide range of outcomes were extracted from reports included in our evidence review, comprising 81 outcomes in 10 categories, based on a combined study sample of 9263 participants (Table 3). Only a single study in our review showed any significant deleterious effects of Tai Chi practice (张斌南, 王力, 郭义军, 刘晓军, 黄京韬, 宇文展, 2010). In this study, the overall mental health of Tai Chi novices was found to worsen. However, this evidence of a deleterious effect was in conflict with additional supporting and uncertain evidence, meaning that the net evidence score was zero, and so no conclusion could be reached concerning this outcome (outcome 64, Table 3).

Eleven outcomes showed higher uncertain evidence scores than supporting evidence scores, suggesting that these outcomes were not promoted by Tai Chi practice. For example, with a net evidence score of − 32, an increase in the height of the participant seems an unlikely benefit of Tai Chi practice (outcome 13, Table 3). Sixty-five outcomes showed positive net evidence scores, suggesting possible or likely benefit of Tai Chi practice in at least some of these outcomes. Evidence scores appeared to cluster into three strata – we have therefore designated these as low, moderate and high levels of evidence – demonstrating median (range) evidence scores of 8 (-32 to 42), 58 (54 to 80) and 124 (104 to 136) respectively. Sixty nine outcomes demonstrated low evidence scores and are not discussed further (Table 3).

Four outcomes in our results demonstrated a high level of evidence with scores of over 100 with few, or no, uncertain scores, demonstrating likely benefits of Tai Chi practice — these were designated the primary outcomes of our review. Eight secondary outcomes showed moderate levels of evidence, thus demonstrating possible benefits of Tai Chi practice. These primary and secondary outcomes spanned the physical, psychological and psychosocial domains, and are detailed below.

Physical domain

The single primary outcome in the physical domain, with a net evidence score of 104, was increased flexibility (outcome 14, Table 3). Secondary outcomes showing possible benefits of Tai Chi practice in the physical domain comprise increased lung capacity (outcome 28, net evidence of 64), improved balance (outcome 15, net evidence 60), improved 800/1000 m run time (outcome 16, net evidence 56) and improved quality of sleep (outcome 1, net evidence 54). These results would appear to be consistent with improvements in aerobic fitness. However, a relative lack of evidence in other physical activities such as long jump (outcome 19, net evidence 16) or 50/100 m sprint (outcome 27, net evidence − 8) suggest that Tai Chi is less effective in improving anaerobic fitness. This may also be consistent with findings that Tai Chi has little effect on a number of other physiological or body composition outcomes such as reduced body mass index (BMI) (outcome 12, net evidence − 18) or improved overall physical health (outcome 7, net evidence − 24).

Psychological and psychosocial domain

All likely and possible outcomes in this domain are defined by the Symptom Checklist 90 (SCL-90), a well validated self-report instrument testing for a broad range of psychological symptoms. Primary outcomes in the psychological and psychosocial domain that show likely benefit of Tai Chi practice comprise reduced symptoms of depression (outcome 51, net evidence 136), decreased anxiety (outcome 52, net evidence 128) and improved interpersonal sensitivity (outcome 80, net evidence 120). Secondary outcomes showing possible benefit of Tai Chi practice are reduced symptoms of compulsion (outcome 53, net evidence 80), decreased somatization symptoms (outcome 54, net evidence 64), decreased hostility (outcome 55, net evidence 56) and decreased symptoms of phobia (outcome 56, net evidence 56).

Discussion

Our results suggest that Tai Chi is a genuinely integrated health-promoting practice with some physical benefits but also psychological benefits, giving it an advantage over activities that enhance only physical aspects of health. Our results indicate that Tai Chi has aerobic but not anaerobic physical benefits, and this is consistent with the low impact nature of Tai Chi practice. In addition, the cluster of psychological and psychosocial benefits seen in our findings is consistent with the deliberate mindfulness training of Tai Chi, which aims to improve well-being by focusing emotions and sensations on the events occurring in the present moment (Carmody, 2009).

Students in higher education can be at increased risk of specific stress-related disorders such as depression and anxiety — these are serious and debilitating conditions, and our results show a benefit of Tai Chi practice for these conditions in these at-risk populations (Dyrbye et al., 2010, Dyrbye et al., 2006). Increased flexibility may also benefit students in higher education who spend long periods sitting while studying, taking examinations, or during lectures. It is also possible that the fourth primary outcome identified in our study, that of increased interpersonal sensitivity, could also benefit tertiary students by allowing them to better cope with the competitiveness of restricted and high-stakes entry requirements of certain courses, such as medicine.

Strengths and limitations

An important strength of our study is that it is the only systematic review that we are aware of that combines evidence from Chinese and English language reports, including a significant amount of systematically discovered grey literature in the form of Chinese research theses. The inclusion of Chinese-language reports in our study significantly increased the number of sources that were reviewed, which we believe was an important part of gaining a comprehensive view of this holistic health intervention. It also resulted in a complementary set of evidence, allowing a broad comparison of the quality and type of evidence from two quite different cultural contexts. Given the cultural background of Tai Chi, the inclusion of the evidence from Chinese reports is an important part of our review. Our designation of low, moderate and high levels of evidence emerged from the data, but we have reported our results in a transparent way that would allow anyone to designate different thresholds for the levels of evidence if they wished.

Different usage of terminology is an inherent potential bias in a systematic review incorporating reports in two languages. Although there was some supportive evidence of the benefit of Tai Chi in decreasing self-rated stress (outcome 61, net evidence 24), the relative lack of the mention of stress in our findings is likely to reflect the fact this outcome was included specifically only in the English articles. In the Chinese literature this factor was generally included under the term “anxiety” (included as one of the four primary benefits found in our study). In addition, the allocation of studies into a hierarchy of evidence can be difficult when certain details are omitted from the study report. Whenever these difficulties occurred or were suspected in the present study, we assigned the report to the most conservative evidence tier indicated (Table 2).

Our method of ranking and synthesizing the evidence did not allow us to quantify the effect size of outcome measures as is often possible where quantitative measures of like outcomes can be aggregated and standard errors calculated. Other reviews of the benefits of Tai Chi in general populations of participants have excluded data that fails to meet the Level I or Level II evidence criteria (Adams, 2004). However, given the paucity of randomized controlled trials of Tai Chi, particularly involving students in higher education, the inclusion of a large number of reports containing other forms of evidence is a strength of our study, and our method allowed us to do this in a systematic way. Such an approach is also consistent with the principles of evidence-based medicine (Sackett et al., 1996).

Although our results are not inconsistent with the findings of systematic reviews of level I and Level II studies in general participant populations, they show differences that may be expected due to the fact that the students in our results are a predominately younger population (Adams, 2004, Kuramoto, 2006). For example, others have evaluated Tai Chi for its therapeutic application in specific populations of participants suffering various conditions, and found benefits in terms of improved cardiovascular function, pain management, and reduced risk of falls (Adams, 2004). These benefits would not be expected to be seen in young individuals who are generally physically fit. As suggested by our findings, such youthful populations may benefit from Tai Chi quite differently when compared to older populations. However, the evidence for Tai Chi in tertiary students might also be applicable to other youthful cohorts.

The range of outcome measures included in our study and the evidence for both physical and mental benefits of Tai Chi seen in our results indicate the need to carefully consider the key outcome measures in any future study. There is also scope for a wider range of methods to be considered in exploring the benefits of Tai Chi — for instance, interviews, multiple-baseline studies and focus groups were seldom used in the studies we reviewed. Furthermore, new understanding of the neurophysiological processes underlying meditation and other mind-body integrative activities may suggest that new quantitative measures of brain activity during the practice of Tai Chi may be possible and insightful (Reis et al., 2014, Ricard et al., 2014).

Conclusion

Students in higher education practicing Tai Chi benefit significantly in terms of reduced symptoms of depression and anxiety, improved interpersonal sensitivity, and increased flexibility. There remains scope for more research to determine how long and how often students need to practice Tai Chi to achieve the most benefit, and the extent to which Tai Chi may benefit other youthful participant cohorts. The potential of Tai Chi as an effective intervention to reduce health risks for students, with few or no side effects, should be considered along with other strategies taken by higher education institutions to ensure the well-being of their students.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Minxing Luo, a doctor of Traditional Chinese Medicine, for acting as our Chinese translator throughout this project, and to Jennifer Hobson, Subject Librarian, University of Auckland, for assistance with the literature search. This project was supported by a summer studentship stipend from the Faculty of Medical and Health Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Contributor Information

Craig S. Webster, Email: c.webster@auckland.ac.nz.

Anna Y. Luo, Email: yluo027@aucklanduni.ac.nz.

Chris Krägeloh, Email: chris.krageloh@aut.ac.nz.

Fiona Moir, Email: f.moir@auckland.ac.nz.

Marcus Henning, Email: m.henning@auckland.ac.nz.

References

- Adams K.P.J. Comprehensive therapeutic benefits of Taiji. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2004;83:735–745. doi: 10.1097/01.phm.0000137317.98890.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzahem A.M., van der Molen H.T., Alaujan A.H., Schmidt H.G., Zamakhshary M.H. Stress amongst dental students: a systematic review. Eur. J. Dent. Educ. 2011;15:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2010.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2015. http://www.prisma-statement.org Available from. (Accessed 8 December)

- Badr G.A. World Conference on Psychology, Counselling and Guidance, WCPCG-2010. 2010. The impact of interactive exercises for Taiji and ballistic on some physical variables and psychosocial skills and level of the skill performance on a horse jumping; pp. 2098–2102. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell K., Harrison M., Adams M., Triplett N.T. Effect of Pilates and taiji quan training on self-efficacy, sleep quality, mood, and physical performance of college students. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2009;13:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell K., Harrison M., Adams M., Quin R.H., Greeson J. Developing mindfulness in college students through movement-based courses: effects on self-regulatory self-efficacy, mood, stress, and sleep quality. J. Am. Coll. Heal. 2010;58:433–442. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell K., Emery L., Harrison M., Greeson J. Changes in mindfulness, well-being, and sleep quality in college students through Taijiquan courses: a cohort control study. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2011;17:931–938. doi: 10.1089/acm.2010.0645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmody J. Evolving conceptions of mindfulness in clinical settings. J. Cogn. Psychother. 2009;23:270–280. [Google Scholar]

- Chang T., Chang S. 2010. Assessing the Effect of Antioxidative with Yoga and Tai-Chi training. Ergonomic Trends from the East: Proceedings of Ergonomic Trends from the East. Japan, 12–14 November 2008; pp. 263–267. [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye L.N., Thomas M.R., Shanafelt T.D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 2006;81:354–373. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyrbye L.N., Thomas M.R., Power D.V. Burnout and serious thoughts of dropping out of medical school: a multi-institutional study. Acad. Med. 2010;85:94–102. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46aad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esch T., Duckstein J., Welke J., Braun V. Mind/body techniques for physiological and psychological stress reduction: stress management via Tai Chi training — a pilot study. Med. Sci. Monit. 2007;13:CR488–CR497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassed C., Lisle S.D., Sullivan G., Pier C. Enhancing the health of medical students: outcomes of an integrated mindfulness and lifestyle program. Adv. Health Sci. Educ. 2009;14:387–398. doi: 10.1007/s10459-008-9125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J.P.T., Green S. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org (Accessed 8 December 2015) [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J., Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen L.S., Merry A.F., Webster C.S., Weller J., Larsson L. Evidence-based strategies for preventing drug administration errors during anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:493–504. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2004.03670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones M., Johnston D.W. Reducing distress in first level and student nurses: a review of the applied stress management literature. J. Adv. Nurs. 2000;32:66–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01421.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster R.-P., McEwen B.S., Lupien S.J. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2010;35:2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y., Seidlitz L. Spirituality moderates the effect of stress on emotional and physical adjustment. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2002;32:1377–1390. [Google Scholar]

- Knight J.M. Physiological and neurobiological aspects of stress and their relevance for residency training. Acad. Psychiatry. 2013;37:6–10. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.11100187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh T.C. Tai Chi Chuan. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1981;9:15–22. doi: 10.1142/s0192415x81000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuramoto A.M. Therapeutic benefits of Tai Chi exercise: research review. Wis. Med. J. 2006;105:42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-S., Koeske G.F., Sales E. Social support buffering of acculturative stress: a study of mental health symptoms among Korean international students. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2004;28:399–414. [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.S., Lee E.-N., Ernst E. Is tai chi beneficial for improving aerobic capacity? A systematic review. Br. J. Sports Med. 2009;43:569–573. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2008.053272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclean J.A., Strongman K.T., Neha T.N. Psychological distress, causal attributions, and coping. N. Z. J. Psychol. 2007;36:85–92. [Google Scholar]

- Mays N., Pope C., Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy. 2005;10(Suppl. 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McManus I.C., Winder B.C., Gordon D. The causal links between stress and burnout in a longitudinal study of UK doctors. Lancet. 2002;359:2089–2090. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)08915-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C.L., Levenson M.R. Drinking to cope among college students: prevalence, problems and coping processes. J. Stud. Alcohol Drugs. 2002;63:486–497. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penley J.A., Tomaka J., Wiebe J.S. The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: A meta-analytic review. J. Behav. Med. 2002;25:551–603. doi: 10.1023/a:1020641400589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis P.M.R., Hebenstreit F., Gabsteiger F., von Tscharner V., Lochmann M. Methodological aspects of EEG and body dynamics measurements during motion. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014;8:1–19. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard M., Lutz A., Davidson R.J. Mind of the meditator. Sci. Am. 2014;311:22–29. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1114-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D.L., Rosenberg W.M., Gray J.A., Haynes R.B., Richardson W.S. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ. 1996;312:71–72. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiralkar M.T., Harris T.B., Eddins-Folensbee F.F., Coverdale J.H. A systematic review of stress-management programs for medical students. Acad. Psychiatry. 2013;37:158–164. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.12010003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teychenne M., Ball K., Salmon J. Physical activity and likelihood of depression in adults: a review. Prev. Med. 2008;46:397–411. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P.A. Stress and health: major findings and policy implications. J. Health Soc. Behav. 2010;51:S41–S53. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang H.W.H., Chan E.P., Cheung W.M. Effects of mindful and non-mindful exercises on people with depression: a systematic review. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2008;47:303–322. doi: 10.1348/014466508X279260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.Y., An L.G. Effects of 12 weeks' tai chi chuan practice on the immune function of female college students who lack physical exercise. Biol Sport. 2011;28:45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y.T., Taylor L., Pearl M., Chang L.S. Effects of tai chi exercise on physical and mental health of college students. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2004;32:453–459. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X04002107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W.C., Zhang A.L., Rasmussen B. The effect of Tai Chi on psychosocial well-being: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. J. Acupunct. Meridian Stud. 2009;2:171–181. doi: 10.1016/S2005-2901(09)60052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C., Bannuru R., Ramel J., Kupelnick B., Scott T., Schmid C.H. Tai Chi on psychological well-being: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2010;10:23. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-10-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wichianson J.R., Bughi S.A., Unger J.B., Spruijt-Metz D., Nguyen-Rodriguez S.T. Perceived stress, coping and night-eating in college students. Stress. Health. 2009;25:235–240. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf T.M., Kissling G.E. Changes in life-style characteristics, health, and mood of freshman medical students. J. Med. Educ. 1984;59:806–814. doi: 10.1097/00001888-198410000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeh G.Y., Wang C., Wayne P.M., Phillips R.S. The effect of Tai Chi exercise on blood pressure: a systematic review. Prev. Cardiol. 2008;11:82–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7141.2008.07565.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Goodson P. Predictors of international students’ psychosocial adjustment to life in the United States: a systematic review. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2011;35:139–162. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo D.-H. Preventive geriatrics: an overview from traditional Chinese medicine. Am. J. Chin. Med. 1982;10:32–39. doi: 10.1142/S0192415X82000063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 任崇伟, 乔婷. 太极拳运动对大学生心理健康影响的初探. 菏泽医学专科学校学报 2008;20:93-4.

- 冀先礼. 太极拳运动对大学生心理健康影响的干预研究. 焦作师范高等专科学校学报 2008;24:39-42.

- 刘永祥, 胥凡, 曹秀玲. 女大学生身心健康与太极拳锻炼的实验研究. 莆田学院学报 2007;14:40-2.

- 刘洪燕. 太极拳对大学生心理健康影响机理的探讨. 体育科技文献通报 2005;13:045.

- 刘笃涛, 马效萍. 太极拳对大学生心理健康的影响. 中国临床康复 2003;7:2252-.

- 包雪鸣. 太极拳课程对高校学生心理健康的影响研究. 心理科学 2008;31:1251-4.

- 卢艳红. 太极拳治疗女大学生原发.性痛经效果及某些机制的研究: Hunan Normal University, 2010.

- 吴永存, 兰孝国. 36 式陈氏太极拳对大学生身心健康影响的实验研究. 搏击: 武术科学 2006:37-9.

- 吴雅彬, 张明明. 太极拳练习对亚健康大学生的影响. 科技信息 2008:199-200.

- 周春太. 太极拳对练对大学生心理健康影响的实验研究. 辽东学院学报: 自然科学版 2010;17:235-8.

- 孙细英, 张瑞洁, 崔璨. 太极拳对非体育专业女大学生身心健康影响的实验研究. 搏击: 武术科学 2008:42-4.

- 孙耀, 花蕊. 太极拳练习对女大学生体质的影响. 北京体育大学学报 2003;26:353-4.

- 孟云鹏. 太极拳传统养生项目对大学生身心健康影响的调查与分析. 阜阳师范学院学报: 自然科学版 2012;29:91-4.

- 安卓炯. 太极拳运动对大学生心血管机能的影响. 体育世界: 学术版 2010:107-8.

- 宋志毅. 陈式太极拳老架一路对高校大学生体质相关指标影响的实验研究: 河南大学, 2010.

- 岳利民. 简化太极拳练习对大学生身体成分和心率变化的影响: 上海师范大学, 2008.

- 崔友琼, 伍鸿鹰, 段小洪. 不同负荷太极拳运动下血生化指标的变化分析. 现代预防医学 2010;37:3881-3.

- 庄静. 太极拳治疗女大学生原发.性痛经效果及某些机制的研究: Beijing Sport University, 2012.

- 庞阳康, 刘仿. 太极拳运动对大学生外周血 T 细胞亚群的影响. 体育学刊 2008;15:100-3.

- 张一龙. 太极拳锻炼对大学生身心保健作用的研究. 吉林体育学院学报 2005;21:144-6.

- 张全海, 范辰. 太极拳对大学生血细胞及下肢平衡能力的影响. 少林与太极 2011:36-40.

- 张均予, 徐美琴. 太极拳运动对大学生身心健康的影响. 江西师范大学学报: 自然科学版 2009;33:622-4.

- 张大力. 太极拳对女大学生脑电 α 波影响的实验研究. 博击体育论坛 2009;1:68-9.

- 张斌南, 王力, 郭义军, 刘晓军, 黄京韬, 宇文展. 长期太极拳练习对男大学生骨健康的影响. 北京体育大学学报 2010;33:62-5.

- 张海利, 张海军. 长期练习太极拳对肥胖大学生脂代谢及关联激素的影响. 沈阳体育学院学报 2011;30:95-8.

- 徐敏娜, 李震. 二十四式太极拳对大学生三维健康的影响. 科技创新导报 2008:203.

- 敬继红, 席永平, 闫文凯. 太极拳的认知方式对治疗大学生抑郁症的功效研究. Sichuan Sports Science 2011:57-63.

- 方敏, 贝迎九, 崔世兵. 大学生参加太极拳锻炼与心理健康的关系. 中国学校卫生 2003;24:290-1.

- 曲喜峰. 太极拳运动对改善大学生身体素质的影响研究. 出国与就业: 就业教育 2011:42.

- 曹永庆, 庄红梅. 太极拳对高职男生体质健康影响的实验研究. 邯郸职业技术学院学报 2008;21:86-8.

- 李云清, 施锦华, 寸若标. 太极拳锻炼对大学生心理健康的影响. 山东电力高等专科学校学报 2006;9:26-8.

- 李凌云. 太极拳对大学生心理健康及身体自尊水平的影响. 山东体育科技 2007;29:43-5.

- 李文娟. 8 周太极拳锻炼对健康女大学生心率变异性等指标的影响: 北京体育大学硕士学位论文, 2010.

- 李晶, 毛明春. 习练简化太极拳对非体育专业女大学生力量素质影响的研究. 搏击: 武术科学 2009;6:42-4.

- 李继刚. 太极拳锻炼对大学生身心健康的影响研究. 广东教育学院学报 2004;24:126-8.

- 李钢, 尹剑春. 太极拳运动对女大学生心境以及安静状态下 β 内啡肽的影响. 北京体育大学学报 2008;31:356-8.

- 李阿特, 孙福成. 太极拳对增强大学生心理健康的实验研究. 辽宁体育科技 2006;28:33-4.

- 杨现新, 李玉周. 太极拳, 剑教学与普通大学生心理素质. 现代预防医学 2006;33:1425-6.

- 杨祥全. 太极拳对普通大学生心理健康影响的实验研究. 天津体育学院学报 2003;18:63-6.

- 林友标, 章舜娇. 太极拳对青少年身心健康影响的研究. 广州体育学院学报 2010;30:105-7.

- 林清. 浅谈太极拳运动对大学生情绪紧张度的影响. 安徽体育科技 2005;26:110-1.

- 毛红妮, 袁丽, 罗名花. 太极拳锻炼对女大学生抑郁与焦虑水平的影响. 新西部: 理论版 2008:232.

- 温元秀, 王蒸仙. 太极拳锻炼对大学生心理健康的影响. 运动 2010:101-2.

- 潘国建, 卢昌亚, 孙绪生, 傅霆, 孙力, 高幕峰. 太极拳运动对大学生能量代谢及形态机能指标的影响. 上海师范大学学报: 自然科学版 2009;38:319-25.

- 牛志宁. 高核太极参选修裸对大母健身体自尊和生活满意底的影响研究: 华东师范大学, 2009.

- 王克海. 太极拳对大学生心理及免疫系统影响的实验研究. 齐齐哈尔医学院学报 2010;31:773-4.

- 王向阳. 太极拳练习对女大学生心血管功能影响的实验研究. 湖南师范大学教育科学学报 2007;6:127-8.

- 王征宇. 太极拳对大学生身心健康的影响. 吉林体育学院学报 2009;25:91-2.

- 王正良. 太极拳训练对女大学生身心健康的影响. 通化师范学院学报 2012;33:89-90.

- 王海波, 康德强, 郑晓光, 刘庆晓. 太极拳必修课程对普通高校大学生心理, 生理状况影响的研究. 搏击: 武术科学 2007:59-61.

- 王超, 申忠华, 罗华. 太极剑锻炼与护理专业女大学生身心健康的实验研究. 湖北体育科技 2008;27:405-6.

- 章璐璐, 黄世伟, 杜寿高. 太极拳运动对培养大学生身心健康价值的研究. 搏击: 武术科学 2011;8:46-7.

- 罗立平. 42 式太极拳对高校体育弱势群体 (大学生) 健身的研究. 吉林体育学院学报 2008;24:165-6.

- 苏勇. 不同频度二十四式太极拳锻炼对女大学生抑郁情绪影响的实验研究: 北京体育大学, 2010.

- 莫连芳, 刘德琼. 医学院校学生太极拳教学保健康复的效应研究. 中小企业管理与科技 2010:195-6.

- 谭路. 太极拳锻炼对大学生心血管功能影响的探讨. 沈阳体育学院学报 2004;23:375-6.

- 赵双印. 太极拳对普通高校大学生人格特征的影响. 中国临床康复 2005;9:33-5.

- 赵珍. 太极拳运动对大学生情绪紧张度的影响. 武汉体育学院学报 2004;38:175-6.

- 闫民. 二十四式太极拳对健康女大学生生理指标影响的研究: 山东师范大学, 2003.

- 陈善平, 张秋君, 李淑娥. 太极拳教学对大学生 A 型行为的影响. 中国体育科技 2005;41:91-3.

- 陈楠. 健美操, 太极拳运动对长春高校女生心理健康影响的研究: 东北师范大学硕士论文, 2009.

- 陈福刁, 陈浩庆, 张帼雄. 太极拳锻炼对大学生身体机能的影响. 沈阳体育学院学报 2006;25:121-3.

- 青春. 二十四式太极拳对大学在A型行为影响的教学实验研究: Inner Mongolia Normal University, 2006.

- 魏晓磊, 梁爽. 太极拳对普通高校大学生心理干预的实验研究. 吉林省教育学院学报: 中旬 2012;28:106-7.

- 魏景杰. 太极拳与健身跑对普通男大学生心肺功能影响的比较研究: 北京体育大学硕士学位论文, 2006.

- 黄勃. 简化二十四式太极拳对女大学生抑郁水平的影响: 北京体育大学, 2008.

- 黄祁平, 万艳平, 戴亏秀, 蒋桂凤, 唐双阳. 太极拳运动增强高年级女大学生体液免疫应答实验研究. 武汉体育学院学报 2006;40:54-6.

- 黄莹仪. 太极拳对大学生心理健康的影响. 科技风 2012:18.