Abstract

Bone marrow adipose tissue (MAT) accounts for up to 70% of bone marrow volume in healthy adults and increases further in clinical conditions of altered skeletal or metabolic function. Perhaps most strikingly, and in stark contrast to white adipose tissue, MAT has been found to increase during caloric restriction (CR) in humans and many other species. Hypoleptinemia may drive MAT expansion during CR but this has not been demonstrated conclusively. Indeed, MAT formation and function are poorly understood; hence, the physiological and pathological roles of MAT remain elusive. We recently revealed that MAT contributes to hyperadiponectinemia and systemic adaptations to CR. To further these observations, we have now performed CR studies in rabbits to determine whether CR affects adiponectin production by MAT. Moderate or extensive CR decreased bone mass, white adipose tissue mass, and circulating leptin but, surprisingly, did not cause hyperadiponectinemia or MAT expansion. Although this unexpected finding limited our subsequent MAT characterization, it demonstrates that during CR, bone loss can occur independently of MAT expansion; increased MAT may be required for hyperadiponectinemia; and hypoleptinemia is not sufficient for MAT expansion. We further investigated this relationship in mice. In females, CR increased MAT without decreasing circulating leptin, suggesting that hypoleptinemia is also not necessary for MAT expansion. Finally, circulating glucocorticoids increased during CR in mice but not rabbits, suggesting that glucocorticoids might drive MAT expansion during CR. These observations provide insights into the causes and consequences of CR-associated MAT expansion, knowledge with potential relevance to health and disease.

Adipocytes are a major component of human bone marrow (BM), comprising up to 70% of BM volume and accounting for over 10% of total adipose mass in lean, healthy adults (1, 2). Such marrow adipose tissue (MAT) further increases in diverse clinical conditions, including aging-associated bone loss and osteoporosis (3), estrogen deficiency (4, 5), type 1 diabetes (6, 7), and during treatment with pharmacological agents such as glucocorticoids, thiazolidinediones, or fibroblast growth factor-21 (FGF21) (8–12). Perhaps most strikingly, MAT is not catabolized during acute starvation (13, 14) but instead increases during anorexia nervosa and other conditions of prolonged caloric restriction (CR) (15–18). This is in stark contrast to white adipose tissue (WAT), underscoring the notion that MAT and WAT are developmentally and functionally distinct. However, both MAT formation and function are poorly understood, and therefore, the impact of MAT on human physiology and disease remains to be established.

Understanding why MAT increases during CR might yield insights into MAT's physiological and pathological functions. Many changes that occur during CR are physiological adaptations that improve the ability to survive and/or recover from starvation (19). Such beneficial adaptations are likely to have been strongly selected for during mammalian evolution (20), and therefore, the fact that MAT expands during CR suggests that MAT might serve an important physiological function. Alternatively, CR-associated MAT expansion might be a neutral, inconsequential phenomenon, or a pathological response that negatively impacts human health (18). Whatever the case, improved knowledge of the causes and consequences of MAT expansion during CR might shed light on the role of MAT in human physiology and disease.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain why MAT increases during CR (18). For example, CR and/or fasting are associated with decreased circulating leptin, estradiol, and IGF-1, and increased circulating FGF21, ghrelin, and cortisol or corticosterone (15, 21–25). Each of these changes has also been linked to increased BM adiposity in other contexts (5, 11, 12, 26–29), and therefore, each of these factors has been proposed as a mediator of CR-associated MAT expansion. The strongest argument has been made for hypoleptinemia (18). In vitro studies suggest that leptin directly inhibits adipogenic differentiation of BM stromal cells (30, 31), whereas MAT is increased in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice (26). Moreover, central or peripheral leptin administration leads to decreased BM adiposity in ob/ob mice (26, 32), type 1 diabetic mice (33), and Sprague-Dawley rats (34). Leptin may promote MAT loss by acting centrally to increase activity of the sympathetic nervous system, a mechanism through which leptin also promotes bone resorption (35). Finally, serum leptin concentrations inversely associate with vertebral BM adiposity in a cohort of healthy and anorexic humans (36). Thus, several lines of evidence support the possibility that hypoleptinemia drives MAT expansion during CR. However, why CR leads to MAT expansion remains to be established.

In addition to MAT formation, the function of MAT during CR has also begun to be addressed. We recently found that, during CR, MAT contributes to increased circulating levels of adiponectin (2), a hormone associated with enhanced insulin sensitivity and fat oxidation, antiatherogenic and anticancer effects. Moreover, we found that in mice with impaired MAT expansion, skeletal muscle adaptations to CR are suppressed (2). These observations support the concept that MAT is an endocrine organ and suggest that MAT exerts systemic effects to impact adaptive responses to CR (2). However, numerous questions remain. For example, does CR alter MAT's expression or secretion of adiponectin, or other endocrine properties of MAT? And does MAT produce other endocrine factors that contribute to systemic effects of CR?

To address these questions, we investigated the effect of moderate or extensive CR in rabbits, a species that allows isolation of relatively large amounts of intact MAT for downstream analysis (2). Surprisingly, these CR regimens did not lead to MAT expansion or increased circulating adiponectin, despite marked bone loss and hypoleptinemia. Conversely, in female mice we found that CR promotes MAT expansion without altering circulating leptin. Our rabbit studies further suggest site-dependent differences in BM adipocyte size and responsiveness to varying degrees of CR. Finally, we found that CR is associated with increased circulating glucocorticoids in mice, but not in rabbits, suggesting that glucocorticoid excess might contribute to MAT expansion during CR. Together, these observations shed new light on the potential mechanisms of MAT formation, the site-dependent nature of MAT characteristics, and the interplay between MAT expansion, bone loss, and circulating adiponectin.

Materials and Methods

Animals and animal care

New Zealand White rabbits were purchased from Harlan Laboratories or were generously provided by Dr Yuqiang Chen (University of Michigan Medical School). Body mass and random-fed blood glucose were recorded weekly. For euthanasia, rabbits were first sedated by im injection of ketamine (40 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) before euthanizing by iv injection of pentobarbital (65 mg/kg) via the marginal ear vein. C57BL/6J mice were bred in-house as described previously (2). Body fat, lean mass, and free fluid were measured in conscious mice using an NMR analyzer (Minispec LF90II; Bruker Optics). The University of Michigan Committee on the Use and Care of Animals approved all animal experiments, with daily care of mice and rabbits overseen by the Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine.

Caloric restriction

For moderate CR in rabbits (Figures 1 and 2 and Supplemental Figures 1 and 2), 15-week-old male rabbits (3.14 ± 0.19 kg, mean ± SD) were randomly assigned into control (n = 5) and CR (n = 6) diet groups. Each group was fed a high-fiber diet (LabDiet 5326). Control rabbits received 100 g/d (31.91 ± 0.19 g/kg body mass/d; mean ± SD), whereas CR rabbits received 70 g/d (23.00 ± 0.35 g/kg body mass/d; mean ± SD), consistent with 30% CR that was found previously to drive MAT expansion in mice (2, 15). For extensive CR in rabbits (Figures 3 and 4 and Supplemental Figure 3), young males (1.04 ± 0.09 kg, mean ± SD) were fed ad libitum from 5 to 6 weeks of age to establish baseline food intake. Rabbits were then randomly assigned to control (n = 6) or CR (n = 6) diet groups. From 6 to 13 weeks of age, control rabbits were fed ad libitum (68.26 ± 4.82 g/kg body mass/d; mean ± SD), whereas CR rabbits were fed 40–50 g/d depending on body mass (30.65 ± 4.92 g/kg body mass/d; mean ± SD); this is consistent with the 50%–70% reduction of ad libitum food intake used in recent rabbit CR studies (37, 38). For comparisons between the moderate and extensive CR cohorts, the following differences are worth considering: firstly, the moderate CR animals were older, and therefore, heavier; secondly, control-fed rabbits in the extensive CR cohort were fed ad libitum, whereas those in the moderate CR cohort were fed 100 g/d (consistent with Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine guidelines). These differences likely explain why percent fat pad mass is greater in the extensive CR controls than in the moderate CR control rabbits (Figure 1B vs Figure 3B). To avoid malnutrition associated with micronutrient deficiency, both groups were fed throughout with a complete diet for growing rabbits (LabDiet 5321). The CR protocol for C57BL/6J mice was described previously (2).

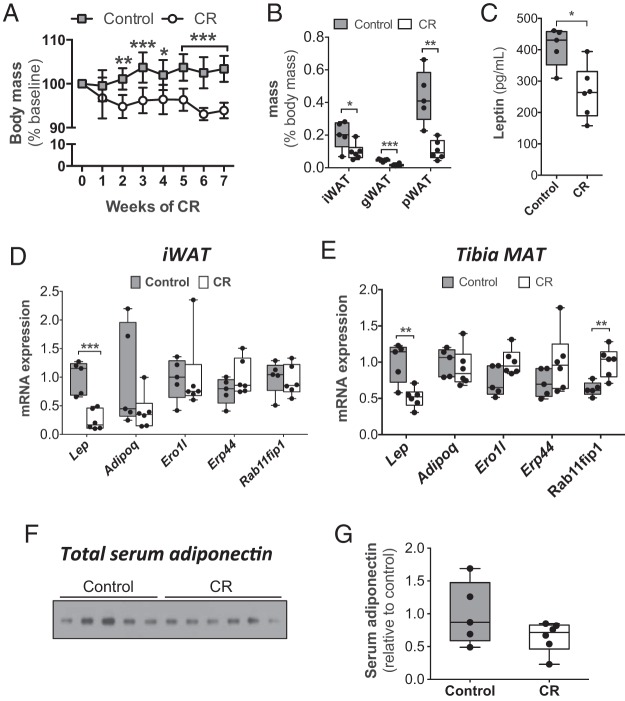

Figure 1.

Circulating adiponectin does not increase during moderate CR in rabbits. Adult male rabbits were fed a control or 30% CR diet from 15 to 22 weeks of age, as described in Materials and Methods. A, Body mass was measured weekly and is presented relative to body mass at 15 weeks of age. B–G, After 7 weeks on CR or control diet, rabbits were euthanized, and fat pads, serum, WAT, and MAT were isolated. B, WAT masses were recorded at necropsy. C, Serum leptin concentrations, as determined by ELISA. D and E, Total RNA was isolated from iWAT (D) and tibial MAT (E). Expression of the indicated transcripts was determined by qPCR and normalized to Ppia expression. F, Immunoblot of total adiponectin in sera from 22-week-old rabbits. E, Densitometry was used to quantify serum adiponectin from F. Data in A are reported as mean ± SD of 5 control and 6 CR rabbits. All other graphs are box and whisker plots. Statistically significant differences between control and CR rabbits are indicated as follows: *, P < .05; **, P < .01; ***, P < .001.

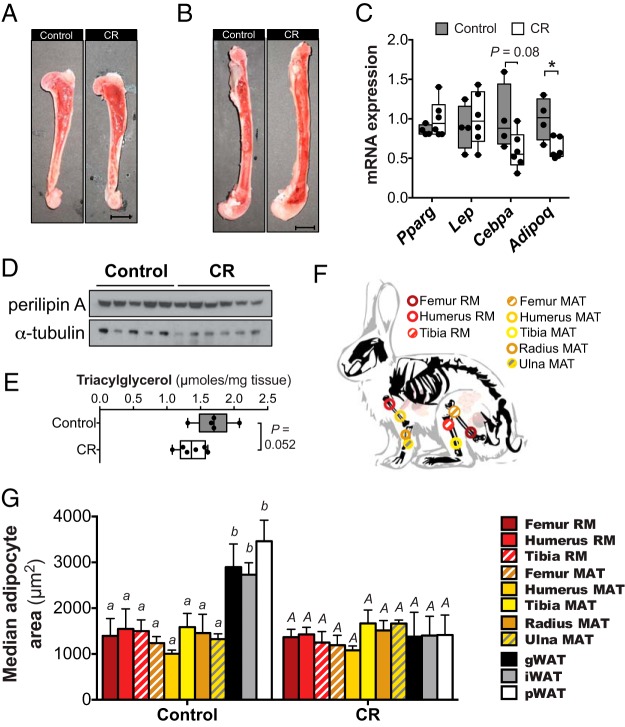

Figure 2.

BM adiposity does not increase during moderate CR in rabbits. Control and moderate CR rabbits (described in Figure 1) were euthanized, and humeri, radii, ulnae, tibiae, and femurs were removed. A and B, Representative images of bisected humeri (A) or femurs (B); scale bar, 1 cm. C–E, Whole, intact BM was isolated from one femur of each rabbit, followed by isolation of total RNA (C), protein (D), or lipid (E). In C, expression of the indicated transcripts was determined by qPCR and normalized to Ppia expression. In D, perilipin A expression was determined by immunoblotting, with α-tubulin used as a loading control. In E, total triacylglycerol was isolated by TLC and the concentration determined by an enzymatic assay. F, Schematic showing the sites from which each sample of RM or MAT was isolated. G, Adipocyte size distribution in the indicated RM, MAT, or WAT samples was determined by quantitative histomorphometry; median adipocyte size was then determined. Data in C and E represent 5 control and 6 CR rabbits and are shown as box and whisker plots. In C, statistically significant differences between control and CR rabbits are indicated by * (P < .05). Data in G are reported as mean ± SD of the next numbers of samples: femur RM: 5 control, 6 CR; humerus RM: 5 control, 6 CR; tibia RM: 3 control, 5 CR; femur MAT: 5 control, 5 CR; humerus MAT: 4 control, 6 CR; tibia MAT: 5 control, 6 CR; radius MAT: 5 control, 6 CR; ulna MAT: 4 control, 6 CR; gWAT, iWAT, or pWAT: 5 control and 6 CR. In G, statistically significant differences in median adipocyte size were assessed by two-way ANOVA. Lowercase letters indicate statistical significance for the control tissues, whereas uppercase letters are used for the CR tissues; samples that do not share a common letter are significantly different from each other (P < .05). Significant effects of CR, within each tissue type, are indicated in Supplemental Figure 2.

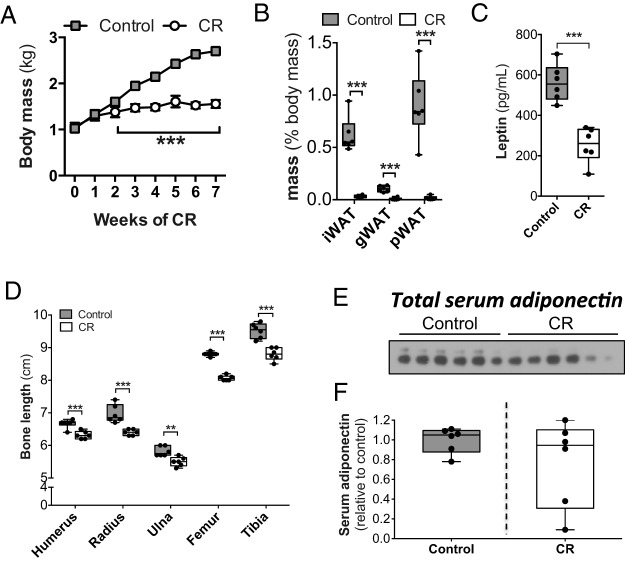

Figure 3.

Circulating adiponectin does not increase during extensive CR in rabbits. Male rabbits were fed ad libitum (control) or at 40% of ad libitum food intake (CR) from 6 to 13 weeks of age. A, Body mass was measured weekly. B–F, After 7 weeks of CR or control diet, rabbits were euthanized and fat pads, serum, and bones were isolated. B, WAT masses were recorded at necropsy. C, Serum leptin concentrations, as determined by ELISA. D, Lengths of the indicated bones were recorded at necropsy. E, Immunoblot of total adiponectin in sera from 13-week-old rabbits. F, Densitometry was used to quantify serum adiponectin from E. Data in A are reported as mean ± SD of 6 control and 6 CR rabbits. All other graphs are box and whisker plots. Statistically significant differences between control and CR rabbits are indicated as described for Figure 1.

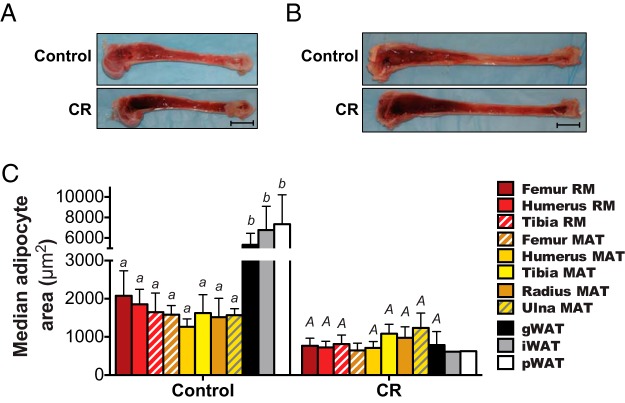

Figure 4.

BM adipocyte size is decreased during extensive CR in rabbits. Control and extensive CR rabbits (described in Figure 3) were euthanized, and humeri, radii, ulnae, tibiae, and femurs were removed. A and B, Representative images of bisected humeri (A) or tibiae (B); scale bar, 1 cm. C, Median adipocyte size in the indicated RM, MAT, or WAT samples was determined by quantitative histomorphometry, as described for Figure 2G. Because of the extent of MAT and WAT loss, from some CR rabbits we were unable to detect any MAT for further analysis. Thus, data in C are reported as mean ± SD of the next numbers of samples: femur RM: 6 control, 4 CR; humerus RM: 5 control, 4 CR; tibia RM: 5 control, 4 CR; femur MAT: 4 control, 2 CR; humerus MAT: 4 control, 4 CR; tibia MAT: 6 control, 4 CR; radius MAT: 5 control, 5 CR; ulna MAT: 6 control, 5 CR; gWAT: 5 control, 3 CR; iWAT: 6 control, 1 CR; pWAT: 5 control, 1 CR. Because femur MAT for the CR group is from only 2 rabbits, the SD of this group represents 0.7071 times the range of the 2 data points. Significant differences are indicated as described for Figure 2G. Data for iWAT and pWAT are from only one CR rabbit, and data for femur MAT are from only 2 CR rabbits; hence, ANOVA could not be used to assess statistical significance for these samples owing to uncertainty over the normality of data distribution.

Blood collection and serum hormone analysis

Blood was sampled from the marginal ear artery of rabbits or the lateral tail vein of mice using Microvette CB 300 capillary collection tubes (Sarstedt). To obtain serum, blood samples were allowed to clot on ice for 2 hours before centrifuging at 3800 RCF (relative centrifugal force) for 5 minutes at 4°C. Serum leptin was determined using an ELISA kit (catalog number MOB00) from R&D Systems, Inc. Total and high-molecular-weight serum adiponectin were determined using an ELISA kit (catalog number 47-ADPHU-E01) from Alpco. ELISA kits to determine concentrations of corticosterone (catalog number ADI-900–097) and cortisol (catalog number ADI-900–071) were from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc.

Analysis of bone morphology by micro computed tomography (μCT)

Femoral heads of rabbits were surgically isolated and embedded in 1% agarose and scanned using a μCT system (μCT100 Scanco Medical). Agarose-embedded femoral heads of rabbits were placed in a 48-mm diameter tube before scanning the femoral neck using the next settings: voxel size 36 μm, 70 kVp, 114 μA, 0.5-mm aluminum filter, and integration time 500 ms. Rabbit trabeculae were analyzed by contouring the inner trabecular compartment using the manufacturer's software (Analysis #15: trabecular, threshold 220), starting 20 slices away from the growth plate and contouring every 10 slices for a total of 30 slices. Density measurements were calibrated to the manufacturer's hydroxyapatite phantom. Analysis was performed using the manufacturer's evaluation software.

Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from tissues using RNA STAT60 reagent (Tel-Test, Inc) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription, primer design, and qPCR were performed as described previously (39). Primers for rabbit Lep, Adipoq, Pparg, Cebpa, Ppia, and Tbp were described previously (2). Sequences for other forward (F) and reverse (R) primers (5′-3′) are as follows: Ero1l, (F) TTGGCTAGAAGGCCTGTGTG and (R) GCCTTCTCCCTCGGTCAAAA; Erp44, (F) CTCCAGCAGATTGCCCTGTT and (R) GGGTGGACTGCTTGCTACAT; and Rab11fip1, (F) CAGTACGGCAGAAGCTCCAA and (R) CCGAGGGGCTGTATTTCTTCA.

Immunoblot analysis

To detect total adiponectin in sera, samples were reduced and denatured by mixing with 4× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) loading buffer, incubating at 95°C for 5 minutes, and cooling on ice for 1 minute before separating by SDS-PAGE, as described previously (40). To isolate total protein, tissues were first pulverized in liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar. Pulverized tissues were then mixed with lysis buffer (1% SDS, 12.7mM EDTA, and 60mM Tris-HCl; pH 6.8) heated to 95°C, and homogenized by sequential passaging through 21- and 26-gauge needles. Lysates were then centrifuged at 20 000 RCF for 15 minutes at 4°C, lipid layers were discarded and supernatants transferred to fresh tubes and stored at −80°C. Protein concentration in tissue lysates was estimated using the BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific). SDS-PAGE, and immunoblotting of tissue lysates was done as described previously (39). Mouse monoclonal anti-adiponectin (MA1–054) and rat monoclonal anti-α-tubulin (MA1-80017) were from Thermo Scientific. Mouse monoclonal anti-perilipin A (4854) was from Vala Sciences.

Isolation of BM, MAT, or red marrow (RM)

To visualize the spatial distribution of MAT and RM in situ, humeri, tibiae, and femurs were longitudinally bisected using a Dremel rotary tool with a 409 cutoff wheel (Robert Bosch Tool Corp); a constant drip of sterile United States Pharmacopeia-grade water was used during cutting to prevent overheating. MAT or RM was then removed using a stainless steel spatula. To isolate MAT from radii or ulnae, epiphyses were removed by lateral incisions with the Dremel tool, thereby allowing access to the marrow cavity. BM was then extruded by first tracing the perimeter of the marrow cavity with a 2-inch, 21-gauge needle, and subsequently scraping the BM out using a stainless steel spatula.

Triacylglycerol content of rabbit femoral BM

One femur of each rabbit was bisected and whole BM removed. BM plugs were then frozen on dry ice before cryopulverization in liquid nitrogen using a pestle and mortar. Total lipid was then extracted from approximately 56 mg of each sample using the Folch method (41) as follows: 1) in a glass vial, mix sample with 1-mL methanol and dissolve by sonication for 4 × 5 minutes, vortexing between each sonication; 2) mix 0.5 mL of tissue/methanol homogenate with 1-mL chloroform and vortex for 30 seconds; 3) add 0.5 mL of 0.1N HCl and vortex the vial to mix; 4) centrifuge for 10 minutes at 500 RCF; 5) remove the top layer and the protein/debris interphase carefully by aspiration under mild vacuum; 6) wash the lower organic layer by adding 0.5 mL of 50% methanol and vortex to mix; 7) centrifuge for 3 minutes at 12 000 RCF; 8) discard upper layer using vacuum aspirator; 9) repeat steps 6–8; 10) transfer 0.3 mL of each sample to a new glass vial and evaporate solvent using nitrogen gas; 11) resuspend the remaining lipid in 100 μL chloroform. These lipid samples were then separated by thin layer chromatography on a silica gel plate; the triacylglycerol bands were then identified and excised. This portion was then extracted from the silica gel and resuspended in 500 μL of 68% ethanol (357 μL of 95% ethanol, plus 143 μL of isotonic saline). The triacylglycerol concentration in 20 μL of each sample was then determined using the Triglyceride Determination kit (Sigma-Aldrich) based on the manufacturer's instructions.

Histology and analysis of adipocyte morphology

Intact pieces of WAT, MAT, and RM were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin, paraffin embedded, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin before determination of adipocyte size distribution, as described previously (42). Analysis of MAT and RM was done without reference to the directionality or orientation within the bone.

Osmium tetroxide staining

Mouse tibiae were stained with osmium tetroxide (number 19170; Electron Microscopy Sciences) and MAT was then visualized by μCT, as described previously (2). MAT volume in distinct tibial regions was then quantified and is presented relative to total tibial marrow volume, as described previously (43). Osmium tetroxide staining could not be used for quantitation of MAT volume in rabbit bones, because the osmium tetroxide is unable to stain beyond the periphery of these large tissues, especially those that are densely packed with fat (E. L. Scheller, unpublished observations).

Statistical analysis

Data are represented as box and whisker plots overlaid with individual values, or as mean ± SD (for data where box and whisker plots would be too cluttered). For box and whisker plots, the box extends from the 25th to 75th percentiles, with the central line representing the median and the whiskers showing the minimum and maximum values. Statistical analysis was done using GraphPad Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software). Significant differences in body mass, tissue mass, circulating leptin, circulating adiponectin, circulating corticosterone, transcript expression, femoral head bone characteristics, BM triacylglycerol, bone length, body composition, and MAT volume were assessed using 2-sample t tests. For moderate CR rabbits, differences in circulating cortisol were assessed using 2-sample t tests; however, for extensive CR rabbits, cortisol concentrations were non-normally distributed, and therefore, significant differences were assessed using the Mann-Whitney U test (see Figure 6 below). Significant differences in adipocyte size were assessed by ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test for multiple comparisons. The D'Agostino test confirmed that adipocyte areas were normally distributed across all tissues for control and CR rabbits. P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

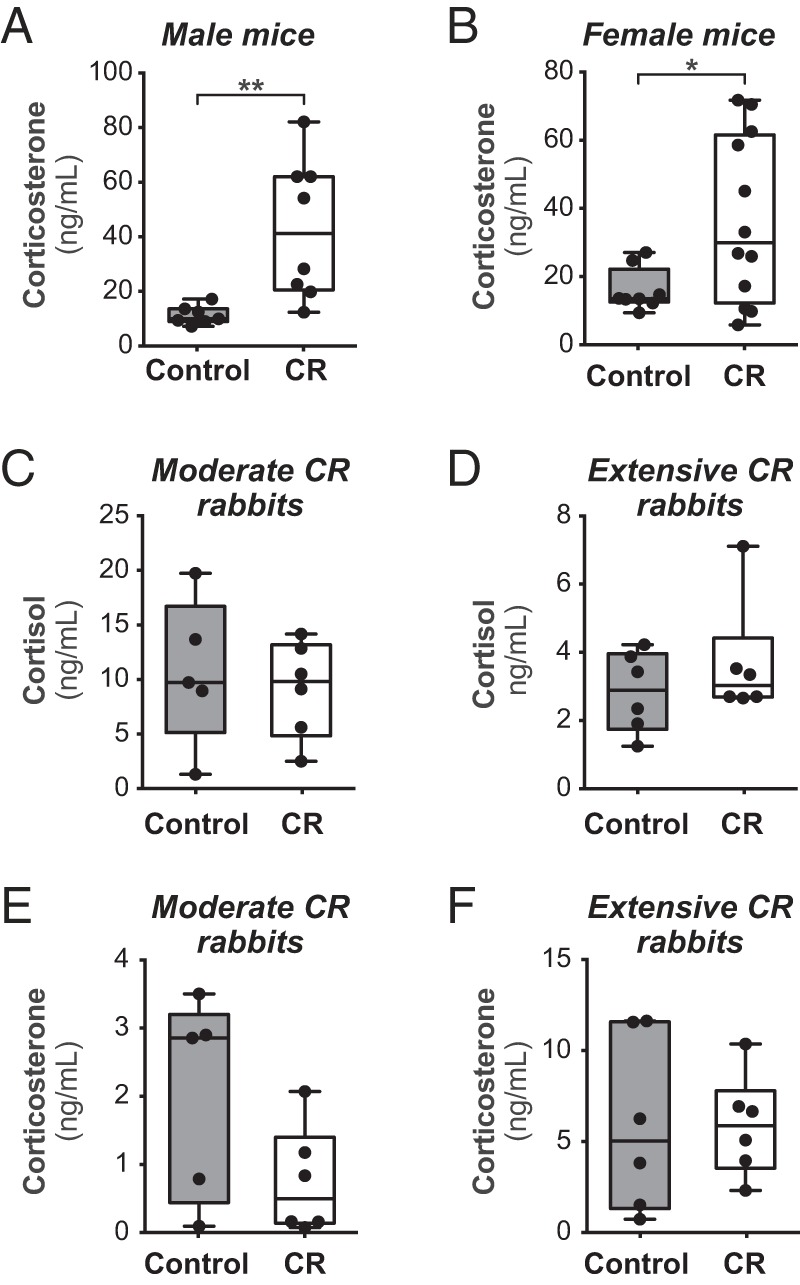

Figure 6.

MAT expansion during CR is associated with changes in circulating glucocorticoids. C57BL/6J mice (A and B) or New Zealand White rabbits (C–F) were fed control or CR diets, as described in Figures 1–5. Blood was sampled at the end of the CR protocols, and concentrations of total corticosterone and cortisol were determined by ELISA. Data are presented as box and whisker plots. Within each group (male mice; female mice; moderate CR rabbits; extensive CR rabbits) statistically significant differences between control and CR animals are reported as described for Figure 1.

Results

Circulating adiponectin does not increase during moderate CR in rabbits

We previously used rabbits to characterize expression and secretion of adiponectin in MAT, because, unlike mice or rats, this species allows isolation of relatively large and intact MAT samples (2). Thus, to investigate further whether CR affects adiponectin production by MAT, we pursued CR studies in rabbits. We fed rabbits in the CR group 30% less food than their control counterparts, consistent with the extent of CR used in our previous mouse studies (2). Here, this 30% CR regimen is described as “moderate” CR. As expected, moderate CR was associated with decreased body mass, circulating leptin, and mass of inguinal WAT (iWAT), gonadal WAT (gWAT), and perirenal WAT (pWAT) depots (Figure 1, A–C, and Supplemental Figure 1). CR-associated bone loss was also apparent, with μCT of femoral heads revealing that CR-fed rabbits had significantly decreased bone volume fraction, connectivity density, and bone mineral content compared with controls (Table 1). To next investigate whether CR impacts adiponectin production by MAT, and how this compares with effects in WAT, we first analyzed expression of adiponectin mRNA (Adipoq). As a positive control, we also measured expression of leptin (Lep), which is known to be decreased in WAT during fasting or CR (44–47). As shown in Figure 1D, CR led to significantly decreased Lep expression in iWAT, whereas adiponectin (Adipoq) expression was not significantly altered by CR. Similar effects were observed in gWAT and pWAT (data not shown). These findings are consistent with observations in rodents and humans (44–50). In tibial MAT, CR was also associated with decreased expression of Lep but not Adipoq (Figure 1E). To begin assessing potential effects on adiponectin secretion, we next analyzed expression of factors known to regulate this process. Ero1-Lα is an ER chaperone that promotes adiponectin secretion, whereas ERp44 and Rab11-FIP1 inhibit adiponectin secretion (51–53). We found that CR did not affect Ero1l, Erp44, or Rab11fip1 expression in iWAT (Figure 1D). Expression of Ero1l and Erp44 in tibial MAT was similarly unaffected, whereas Rab11fip1 expression was significantly higher in MAT of CR-fed rabbits (Figure 1E). These observations are consistent with the concept that adiponectin secretion from WAT does not increase during CR (54) and suggest that this is also true for tibial MAT. However, there is often a disparity between adiponectin transcript expression and circulating adiponectin levels (48, 50, 55). Thus, we next used immunoblotting to assess total adiponectin in serum, expecting that, as in rodents and humans (48, 56), this would increase with moderate CR. Counter to these expectations, total serum adiponectin did not differ between control and CR-fed rabbits (Figure 1, F and G). Thus, moderate CR in rabbits exerts expected effects on body mass, fat mass, bone mass, circulating leptin, and expression of leptin and adiponectin in WAT; however, moderate CR in rabbits is not associated with hyperadiponectinemia.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Femoral Heads of Control and CR Rabbits, as Assessed by μCT

| Control | CR | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TV (mm3) | 35.91 ± 0.83 | 39.87 ± 3.59 | .352 |

| BV (mm3) | 7.07 ± 3.32 | 7.05 ± 1.7 | .167 |

| BVF (%) | 27.1 ± 2.0 | 21.6 ± 1.0 | .032 |

| Conn. Dens | 9.62 ± 0.81 | 7.46 ± 0.47 | .041 |

| SMI | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.88 ± 0.17 | .211 |

| Tb.N | 2.60 ± 0.09 | 2.48 ± 0.05 | .271 |

| Tb.Th | 0.174 ± 0.01 | 0.170 ± 0.01 | .513 |

| Tb.Sp | 0.366 ± 0.02 | 0.40 ± 0.01 | .082 |

| BMC (mg HA) | 286.70 ± 15.14 | 231.49 ± 10.85 | .014 |

TV, trabecular volume; BV, bone volume; BVF, BV fraction; Conn. Dens, connectivity density; SMI, structure model index; Tb.N, trabecular number; Tb.Th, trabecular thickness; Tb.Sp, trabecular spacing; BMC, bone mineral content; mg HA, milligrams of hydroxyapatite.

MAT expansion does not occur during moderate CR in rabbits

Our recent work reveals that in mice, CR-associated hyperadiponectinemia is blunted when MAT expansion is impaired (2). Therefore, the lack of hyperadiponectinemia observed above suggests that MAT expansion might be limited or absent during moderate CR in rabbits. To address this possibility, we bisected bones of these animals and characterized BM adiposity. The BM of each group appeared grossly similar, with no differences in the amount of fatty yellow marrow in humeri and femurs (Figure 2, A and B), or in radii, ulnae, and tibiae (data not shown). To further assess MAT content, we analyzed whole femoral BM for expression of transcripts and proteins typical of BM adipocytes, as well as total triacylglycerol content; unlike the above qPCR analysis of tibial MAT (Figure 1E), these analyses sought to determine adipocyte content in more heterogeneous femoral BM samples. Control and moderate CR-fed rabbits had similar BM expression of Pparg and Lep transcripts (Figure 2C), and expression of Perilipin A protein was also similar (Figure 2D). In contrast, moderate CR was associated with a trend for decreased Cepba expression and significantly lower Adipoq expression (Figure 2C). Similarly, total femoral BM triacylglycerol content tended to be lower with moderate CR (Figure 2E). These observations suggest that moderate CR does not lead to MAT expansion.

To fully determine the impact of CR on BM adiposity throughout the skeleton, we analyzed adipocyte size distribution in MAT and RM obtained from different skeletal sites (Figure 2, F and G, and Supplemental Figure 2). As shown in Supplemental Figure 2, CR did not affect adipocyte size in any MAT or RM depot analyzed, except in ulnae, where CR led to a small but significant increase in adipocyte size (Supplemental Figure 2H). This suggests depot-specific variation in MAT responsiveness to CR. Indeed, in CR-fed rabbits the adipocytes in distal MAT depots (tibia, radius, and ulna) tended to be larger than those in proximal MAT (femur and humerus) (Figure 2F). For further comparison, we also analyzed adipocyte sizes in WAT. In contrast to RM or MAT, CR led to markedly decreased adipocyte size in iWAT, gWAT, and pWAT (Figure 2G and Supplemental Figure 2I). WAT adipocytes were also significantly larger than BM adipocytes in control-fed rabbits, but not after CR (Figure 2G). Thus, adipocyte size and responsiveness to CR differs both between BM and WAT, and also across different MAT depots.

Together, these analyses of BM triacylglycerol content, adipocyte marker expression, and adipocyte size demonstrate that in rabbits, moderate CR does not lead to MAT expansion.

Extensive CR in rabbits leads to BM adipocyte hypotrophy, suggesting loss of MAT

The lack of hyperadiponectinemia and MAT expansion during these moderate CR studies was unexpected. Given that effects of CR are dependent upon the degree of restriction (47, 57, 58), one possibility is that that the extent of moderate CR was insufficient to drive hyperadiponectinemia or MAT expansion. Another possible explanation relates to the fact that our above studies were in skeletally mature rabbits, whereas previous research into CR-associated MAT expansion in mice has been done in young, growing animals (2, 15). To address these possibilities, we next investigated the effects of more extensive CR in a cohort of young, growing rabbits. As found above for moderate CR (Figure 1), extensive CR was associated with significantly decreased body mass, fat pad mass, and circulating leptin (Figure 3, A–C); however, each of these changes was more pronounced than those that occurred during moderate CR (Figure 1, A–E). Bone length was also markedly decreased with extensive CR (Figure 3D), consistent with suppressed skeletal development observed in previous rabbit CR studies (59). Thus, extensive CR was associated with expected effects on body mass, peripheral adiposity, circulating leptin, and skeletal biology. However, as found for moderate CR, extensive CR did not affect total circulating adiponectin (Figure 3, E and F).

We next assessed BM adiposity. Upon bisecting bones for MAT isolation we were struck by the very dark appearance of BM in the extensive CR-fed rabbits (Figure 4, A and B), suggesting decreased BM adiposity in these animals. Indeed, we were unable to isolate intact pieces of MAT from extensive CR-fed rabbits, which prevented us from analyzing MAT adiponectin production in these animals. However, we could isolate small pieces of less pure MAT from the radius and ulna, and from distal regions of the humerus, femur, and tibia. Thus, to further assess effects of extensive CR on BM adiposity we analyzed adipocyte size distribution in these MAT samples, and in RM obtained from humeri, femurs, and tibiae. For comparison, we also analyzed adipocyte sizes in WAT. We found that extensive CR led to significantly reduced adipocyte size in each WAT depot; in humerus MAT and RM; and in femoral and tibial RM (Figure 4C and Supplemental Figure 3). There was also a trend for decreased adipocyte size in radial MAT (P = .068) and tibial MAT (P = .077). Such hypotrophy suggests lipolytic breakdown of BM adipocytes and/or impaired MAT development, possibilities that remain to be formally tested; however, these possibilities are highly likely based on current understanding of adipose tissue biology, and are consistent with the conclusion that extensive CR leads to MAT depletion. One notable exception was the ulna, where CR did not affect adipocyte size (Supplemental Figure 3H). As noted for moderate CR (Figure 2G), in extensive CR rabbits the distal MAT depots (tibia, radius, and ulna) tended to have larger adipocytes than more proximal depots (femur and humerus) (Figure 4C). Differences in adipocyte size were even more pronounced between BM and WAT, with gWAT, iWAT, and pWAT of control-fed rabbits having significantly larger adipocytes than any of the RM or MAT depots (Figure 4C). Thus, as found for the moderate CR cohort, in control rabbits BM adipocytes are smaller than WAT adipocytes, and the response of BM adipocytes to extensive CR varies across the different skeletal sites. Ultimately, both moderate CR and extensive CR led to decreased circulating leptin without resulting in MAT expansion.

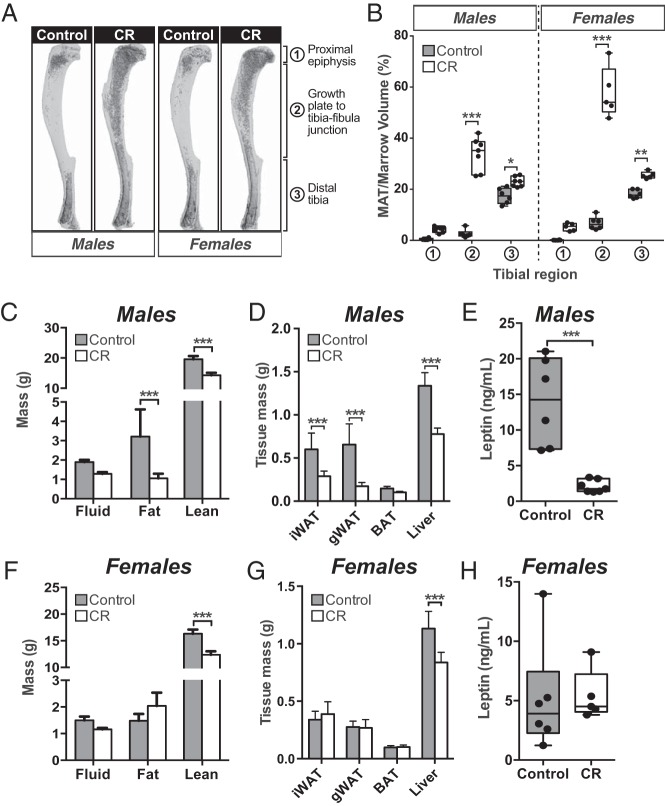

MAT expansion is not associated with hypoleptinemia during CR in female mice

The above findings demonstrate that hypoleptinemia per se is not sufficient to cause MAT expansion, at least in rabbits. To determine the relevance of this finding to other species, we next investigated the relationship between CR, leptin, and MAT expansion in mice. We fed male and female C57BL/6J mice a control or 30% CR diet from 9–15 weeks of age and analyzed MAT, total adiposity, lean mass, and circulating leptin. As expected, in both sexes CR was associated with decreased body mass (Supplemental Figure 4, A and B), hyperadiponectinemia (Supplemental Figure 4, C and F), and significant MAT expansion, as assessed by analysis of osmium tetroxide-stained tibiae (Figure 5, A and B). MAT expansion occurred predominantly in the proximal tibia, from the growth plate to tibia-fibula junction, consistent with this region containing “regulated” MAT (rMAT) that is more responsive to external stimuli than the “constitutive” MAT (cMAT) in the distal tibia (43). However, other effects of CR differed between males and females. Thus, in males CR led to decreases in total adiposity and the masses of iWAT, gWAT, and liver, both in terms of absolute mass (Figure 5, C and D) and percent body mass (Supplemental Figure 4, D and E). Consistent with this decreased adiposity, circulating leptin was markedly lower in CR-fed males compared with their control counterparts (Figure 5E). In contrast, in females CR did not decrease the absolute masses of iWAT, gWAT, or total body fat, despite decreased body mass (Figure 5, F and G, and Supplemental Figure 4B). As such, CR in females was associated with significantly increased body fat percentage and percent iWAT mass, whereas percent lean mass was decreased (Supplemental Figure 4, G and H). Thus, unlike in male mice, CR in female mice led to loss of lean mass without decreasing WAT mass or total adiposity. Consistent with this maintenance of fat mass, circulating leptin did not differ between CR-fed females and their control counterparts (Figure 5H). These observations demonstrate that in female mice, CR-associated MAT expansion is not associated with hypoleptinemia, suggesting that the latter is not required for MAT expansion.

Figure 5.

In female mice CR increases MAT without decreasing circulating leptin. Male and female C57BL/6J mice were fed ad libitum or a 30% CR diet from 9 to 15 weeks of age. A and B, Tibiae from 15-week-old mice were stained with osmium tetroxide followed by μCT analysis. A, Representative μCT scans of osmium tetroxide-stained tibiae. MAT appears as darker regions within each bone. B, MAT volume within each tibial region was determined from μCT scans. C and F, Body composition of 15-week-old live mice was determined by NMR. D and G, Masses of the indicated tissues were recorded at necropsy. E and H, Blood was sampled from the lateral tail vein of 15-week-old live mice. Serum was isolated, and leptin concentrations were determined by ELISA. Data in C and D and F and G are reported as mean ± SD of the next numbers of mice: male control, n = 6; male CR, n = 7; female control, n = 6; female CR, n = 5. All other graphs are box and whisker plots. For each sex, statistically significant differences between control and CR animals are reported as described for Figure 1.

MAT expansion during CR is associated with increased circulating glucocorticoids

The above observations show that MAT expansion occurs during CR in mice but not in rabbits, and that this is not associated with hypoleptinemia. Therefore, we next investigated whether there is another endocrine basis for this differential response. One well-established effect of CR is to increase levels of circulating glucocorticoids, such as cortisol in humans and corticosterone in rodents (25, 60). In contrast, one study finds that glucocorticoids are not increased during CR in rabbits (61). This supports the possibility that differential MAT expansion during CR in mice and rabbits might relate to divergent effects on circulating glucocorticoids. Therefore, we next analyzed circulating glucocorticoids in our cohorts of mice and rabbits with or without CR. Consistent with previous studies, serum concentrations of corticosterone, the major circulating glucocorticoid in rodents, were increased during CR in male and female mice (Figure 6, A and B). In contrast, circulating cortisol and corticosterone were unaltered during moderate or extensive CR in rabbits (Figure 6, C–F). These observations support the possibility that increases in circulating glucocorticoids are a stimulus for CR-associated MAT expansion.

Discussion

In the present study, our original aim was to determine how CR affects adiponectin production by MAT. However, in pursuing this goal we found, unexpectedly, that CR in rabbits does not lead to increased circulating glucocorticoids, MAT expansion, or hyperadiponectinemia. Conversely, in female mice CR-associated MAT expansion occurs without decreased circulating leptin, whereas in both males and females CR is associated with increased serum corticosterone. Together, these observations provide insights into the mechanisms of MAT expansion, the impact of MAT on bone remodeling, and the potential function of MAT as an endocrine organ.

Unexpected effects of CR in rabbits

The lack of MAT expansion during moderate or extensive CR in rabbits was unexpected, because increased BM adiposity during CR has been observed repeatedly in other species (18). However, although previous rabbit studies report maintenance of BM adipocyte size even after 10–21 days' starvation (13, 14), there are no reports of increased MAT during CR in rabbits. Instead, MAT loss has been noted in rabbits when food deprivation extends beyond 25 days (62, 63), which is far shorter than the 7-week timeframe of our CR studies. Thus, extensive CR can lead to MAT loss in rabbits. Similarly, in anorexia nervosa MAT expansion occurs in patients with more minimal weight loss, whereas BM lipid content and adipocyte size decrease in patients with the greatest weight loss (17). In severely anorexic patients, BM becomes serous-like, with atrophy of adipocytes and hematopoietic cells (64). MAT loss after extensive CR has also been reported in other species (65). One limitation of our extensive CR studies is that we did not sample total BM from any bones; hence, unlike for the moderate CR rabbits, we could not analyze other markers of MAT content, such as total triacylglycerol. It is also plausible that extensive CR causes BM adipocyte hypotrophy not because of MAT loss, but as a result of constraints imposed by decreased bone size (Figure 3D); however, this is perhaps unlikely given that CR also increases BM volume via bone loss (2), which may compensate for decreases in bone size. Ultimately, the marked BM adipocyte hypotrophy in extensive CR rabbits, together with the darker appearance of BM in this group, supports the conclusion of MAT loss in this context. Together with the preclinical and clinical studies described above, our findings demonstrate that MAT depletion can occur when the degree and duration of CR are sufficient.

Although CR can cause MAT loss, we find that CR-associated adipocyte hypotrophy is far greater in WAT than in MAT. Thus, MAT adipocytes might be more resistant to lipolysis than adipocytes in WAT. Moreover, it is notable that, in moderate and extensive CR, adipocytes in WAT and MAT reach a similar size. This suggests that MAT adipocyte size might represent a minimum threshold for adipocytes, both in MAT and WAT, which is defended in catabolic states.

Sexually dimorphic effects of CR

In addition to the lack of MAT expansion in rabbits, our finding that CR does not decrease WAT mass or circulating leptin in female mice was initially unexpected; however, our observations are consistent with previous CR studies in female C57BL/6 mice. For example, Varady et al observe increased scWAT and unaltered leptin after 25% CR from 7 to 11 weeks of age (66); Fenton et al report no change in leptin after 30% CR from 6 to 16 weeks of age (67); and Li et al find increased adiposity after 5% CR from 13 to 16 or 15 to 19 weeks of age (68). Our finding that CR decreases adiposity and circulating leptin in male C57BL/6J mice is also consistent with previous studies (15, 69, 70), which suggests that responses to CR in C57BL/6J mice are sex specific. Similarly, Shi et al showed that CR in FVBN mice leads to hypoleptinemia and decreased scWAT mass in males but not females (71). Such sexually dimorphic effects of CR have also been noted in many other species (72–74). In humans, several CR studies report greater loss of total or visceral fat mass in men than in women (75–78); however, this has not been found in all studies (79, 80), and therefore, the relevance of such sexual dimorphism to humans remains to be established. Given the extensive interest in potential benefits of CR to human health (81), this issue clearly warrants further investigation.

Endocrine factors as potential mediators of CR-associated MAT expansion

Our observations in rabbits and female mice suggest that hypoleptinemia per se is neither necessary nor sufficient for MAT expansion during CR, which contradicts the hypothesis that hypoleptinemia is a key driver of CR-associated MAT expansion (18). This hypothesis is indirectly supported by observations that leptin-deficient mice have increased MAT, which decreases after exogenous leptin administration (26, 32–34, 82). This leptin supplementation approach could also be used during CR to directly test whether hypoleptinemia is required for MAT expansion. Here, it would be important to ensure that such leptin supplementation does not increase circulating leptin to supraphysiological concentrations. Indeed, exogenous leptin administration also leads to profound MAT loss in animals that are not leptin deficient (34, 82, 83). In such states of leptin sufficiency, effects of exogenous leptin typically depend upon administration of high doses that elevate circulating leptin to supraphysiological concentrations (84). In contrast, our results demonstrate that hypoleptinemia alone, within a normal physiological range, is not sufficient for CR-associated MAT expansion in rabbits, whereas lack of hypoleptinemia, without resorting to exogenous leptin treatment, does not prevent MAT expansion during CR in female mice. Moreover, estrogen deficiency is associated with increases in MAT and circulating leptin (4, 85), demonstrating that hypoleptinemia is not required for MAT expansion in other contexts. Nevertheless, it remains possible that our observations in rabbits and female mice are species, sex, age, and/or protocol specific. For example, we cannot exclude the possibility that hypoleptinemia contributes to MAT expansion in male C57BL/6J mice, or that moderate CR would promote MAT expansion in younger rabbits. Therefore, there is clear utility in pursuing leptin supplementation experiments to directly test whether hypoleptinemia is required for MAT expansion during CR.

The basis for our observed species-specific differences in MAT expansion remains to be firmly established. As described in the introduction, several endocrine changes have been proposed to contribute to MAT expansion during CR, including decreased IGF-1 and increases in FGF21 or glucocorticoids. Circulating FGF21 increases during short-term fasting (23, 24), but recent studies demonstrate no differences during longer-term CR (86). This argues against a role of FGF21 excess in driving MAT expansion during CR. In contrast, decreased IGF-1 is well established during anorexia nervosa in humans (60) and CR in rodents (58), supporting the possibility that this contributes to MAT expansion; however, IGF-1 also decreases during CR in rabbits (87), and therefore, this is unlikely to account for the differences in MAT expansion observed between rabbits and mice. Moreover, CR in non-anorexic humans was recently shown to decrease bone mass without affecting circulating IGF-1 (88), demonstrating that decreased IGF-1 is not necessary for effects of CR on bone.

Our present findings suggest that the species-specific differences in MAT expansion may relate to effects on circulating glucocorticoids. CR-induced increases in circulating glucocorticoids are well established in rodents and humans, but only one previous study reports the lack of this response in rabbits (61). Our observations therefore build on this work by further demonstrating that, unlike in other species, circulating cortisol and corticosterone do not increase during CR in rabbits. Given that glucocorticoids increase BM adiposity (11), our findings support the possibility that increased circulating glucocorticoids are necessary for CR-associated MAT expansion. We are currently investigating this hypothesis further.

Depot-specific differences in MAT characteristics

Two previous studies report that adipocytes in pWAT are larger than those in femoral RM (14, 89), consistent with our present findings that BM adipocytes are smaller than those in WAT. However, our study is the first to comprehensively compare BM adipocyte sizes across different skeletal sites. We found that adipocytes in distal regions of the skeleton (tibia, radius, and ulna) tend to be larger than those in MAT from more proximal depots (femur and humerus). Responsiveness to CR also varies across these sites: unlike adipocytes in more proximal BM regions, adipocytes in ulnal MAT undergo hypertrophy during moderate CR and resist hypotrophy during extensive CR. This is consistent with an early study of starvation in rabbits, which shows that BM adiposity decreases more in proximal bones (eg, humeri and femurs) than in distal regions (eg, tibiae, radii, and ulnae) (63). This is also consistent with our recent research that identifies regionally distinct MAT subtypes with different characteristics: cMAT exists at distal sites and is relatively refractory to external stimuli, whereas rMAT is interspersed within RM at proximal skeletal sites and is more responsive to external stimuli, such as cold exposure (43). Our present analyses confirm and extend these observations by revealing that CR-associated MAT expansion predominantly occurs within rMAT, whereas increases in cMAT are far less pronounced (Figure 5, A and B). Determining whether these site-specific differences extend to other MAT properties might provide fundamental insights into MAT formation and function.

Relationship between MAT expansion and bone loss

Our results shed further light on the relationship between MAT and bone. Given that MAT is increased in osteoporosis (3), BM adipocytes have been postulated to directly inhibit bone formation and/or promote bone resorption (90–93). Indeed, increased MAT volume is now considered a clinical risk factor for fracture (94). However, this concept is coming under scrutiny after numerous recent studies (95). For example, across several inbred mouse strains there is no correlation between BM adipocyte numbers and femoral bone mineral density (96), whereas blocking MAT expansion does not prevent bone loss during type 1 diabetes or ovariectomy (33, 97, 98). Our observations in rabbits further demonstrate that MAT expansion is not necessary for bone loss during CR. Such knowledge has direct clinical relevance to diseases such as anorexia nervosa, which is associated with bone loss and life-long increases in fracture risk (3, 99). It remains possible that altered MAT characteristics, independent of MAT expansion, contribute to bone loss in osteoporosis, type 1 diabetes, CR, or other conditions. However, our present study provides further evidence that MAT expansion per se does not promote bone loss.

Potential endocrine functions of MAT

Our previous research supports the concept that MAT is an endocrine organ that contributes to hyperadiponectinemia during CR (2). This conclusion is partly based on the observation that increased MAT is required for full increases in circulating adiponectin during CR, at least in mice. Here, we find that neither MAT nor circulating adiponectin increases during CR in rabbits, whereas in mice, the increases in MAT and circulating adiponectin are greater in females than in males. These observations further support the concept that CR-associated hyperadiponectinemia is linked to MAT expansion. Our rabbit studies also reveal that MAT leptin expression decreases during CR, a phenomenon well established in WAT (44, 47). In contrast, we find that CR does not increase adiponectin expression in MAT or WAT. Our data also support the possibility that secretion of adiponectin is not increased, at least based on the expression of known regulators of adiponectin secretion. Similar observations have been made for WAT of rodents and humans (47–50, 54); however, given the lack of hyperadiponectinemia and MAT expansion during CR in rabbits, the relevance of these observations to MAT of humans and other species remains unclear. This uncertainty, as well as the inability to isolate sufficient MAT from extensive CR rabbits, limited our ability to more comprehensively investigate the endocrine properties of MAT. Thus, establishing how CR affects MAT's potential endocrine functions will require further studies in other species. Such research will be crucial if we are to better understand MAT's nascent role as an endocrine organ, as well as the impact of MAT on human health and disease.

Acknowledgments

We thank Greg Whitlock for providing the Dremel tool for rabbit bone bisection and Janet Cawthorn, Abigail Moon, and Dennis Simon for assistance with the rabbit CR studies.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R24 DK092759 (to O.A.M.), K99-DE024178 (to E.L.S.), 5-T32-HD007505 (to A.A.B.), S10-RR026475–01 (to the University of Michigan School of Dentistry microCT Core), and P30 DK089503 (to the Michigan Nutrition Obesity Research Center, who oversaw NMR analysis of mouse body composition). W.P.C. is supported by a Career Development Award (MR/M021394/1) from the Medical Research Council (United Kingdom) and by a Chancellor's Fellowship from the University of Edinburgh, and previously was supported by a Lilly Innovation Fellowship Award and by a Postdoctoral Research Fellowship from the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851 (United Kingdom). H.M. was supported by a mentor-based postdoctoral fellowship from the American Diabetes Association. C.M.H.R. was supported by a Summer Studentship from the Society for Endocrinology (United Kingdom). R.J.S. is supported by a PhD Studentship from the British Heart Foundation.

Disclosure Summary: W.P.C. held a postdoctoral fellowship funded by Eli Lilly and Company; V.K. is employed by Eli Lilly and Company; and O.A.M. has received research funding from Eli Lilly and Company. S.D.P., E.L.S., H.A.P., B.S.L., C.M.H.R., R.J.S., A.A.B., A.K.D., B.R.S., H.M., A.J.B., and B.S. have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BM

- bone marrow

- cMAT

- “constitutive” MAT

- CR

- caloric restriction

- F

- forward primer

- FGF21

- fibroblast growth factor-21

- gWAT

- gonadal WAT

- iWAT

- inguinal WAT

- MAT

- marrow adipose tissue

- μCT

- micro computed tomography

- pWAT

- perirenal WAT

- qPCR

- real-time quantitative PCR

- R

- reverse primer

- RCF

- relative centrifugal force

- RM

- red marrow

- rMAT

- “regulated” MAT

- SDS

- sodium dodecyl sulfate

- WAT

- white adipose tissue.

References

- 1. Hindorf C, Glatting G, Chiesa C, Lindén O, Flux G, EANM Dosimetry Committee. EANM Dosimetry Committee guidelines for bone marrow and whole-body dosimetry. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1238–1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cawthorn WP, Scheller EL, Learman BS, et al. Bone marrow adipose tissue is an endocrine organ that contributes to increased circulating adiponectin during caloric restriction. Cell Metab. 2014;20:368–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fazeli PK, Horowitz MC, MacDougald, et al. Marrow fat and bone–new perspectives. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Martin RB, Chow BD, Lucas PA. Bone marrow fat content in relation to bone remodeling and serum chemistry in intact and ovariectomized dogs. Calcif Tissue Int. 1990;46:189–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Syed FA, Oursler MJ, Hefferanm TE, Peterson JM, Riggs BL, Khosla S. Effects of estrogen therapy on bone marrow adipocytes in postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1323–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Botolin S, Faugere MC, Malluche H, Orth M, Meyer R, McCabe LR. Increased bone adiposity and peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor-γ2 expression in type I diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3622–3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Botolin S, McCabe LR. Bone loss and increased bone adiposity in spontaneous and pharmacologically induced diabetic mice. Endocrinology. 2007;148:198–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ali AA, Weinstein RS, Stewart SA, Parfitt AM, Manolagas SC, Jilka RL. Rosiglitazone causes bone loss in mice by suppressing osteoblast differentiation and bone formation. Endocrinology. 2005;146:1226–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tornvig L, Mosekilde LI, Justesen J, Falk E, Kassem M. Troglitazone treatment increases bone marrow adipose tissue volume but does not affect trabecular bone volume in mice. Calcif Tissue Int. 2001;69:46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ackert-Bicknell CL, Shockley KR, Horton LG, Lecka-Czernik B, Churchill GA, Rosen CJ. Strain-specific effects of rosiglitazone on bone mass, body composition, and serum insulin-like growth factor-I. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1330–1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vande Berg BC, Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Devogelaer JP, Maldague B, Houssiau FA. Fat conversion of femoral marrow in glucocorticoid-treated patients: a cross-sectional and longitudinal study with magnetic resonance imaging. Arthritis Rheum. 1999;42:1405–1411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wei W, Dutchak PA, Wang X, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 promotes bone loss by potentiating the effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:3143–3148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tavassoli M. Differential response of bone marrow and extramedullary adipose cells to starvation. Experientia. 1974;30:424–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bathija A, Davis S, Trubowitz S. Bone marrow adipose tissue: response to acute starvation. Am J Hematol. 1979;6:191–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Devlin MJ, Cloutier AM, Thomas NA, et al. Caloric restriction leads to high marrow adiposity and low bone mass in growing mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25:2078–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bredella MA, Fazeli PK, Miller KK, et al. Increased bone marrow fat in anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:2129–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Abella E, Feliu E, Granada I, et al. Bone marrow changes in anorexia nervosa are correlated with the amount of weight loss and not with other clinical findings. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;118:582–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Devlin MJ. Why does starvation make bones fat? Am J Hum Biol. 2011;23:577–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McCue MD. Starvation physiology: reviewing the different strategies animals use to survive a common challenge. Comp Biochem Physiol A Mol Integr Physiol. 2010;156:1–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kirkwood TL, Kapahi P, Shanley DP. Evolution, stress, and longevity. J Anat. 2000;197(pt 4):587–590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Nedvídková J, Krykorková I, Barták V, et al. Loss of meal-induced decrease in plasma ghrelin levels in patients with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:1678–1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Misra M, Miller KK, Cord J, et al. Relationships between serum adipokines, insulin levels, and bone density in girls with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2046–2052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E. Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARα and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab. 2007;5:426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Inagaki T, Dutchak P, Zhao G, et al. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARα-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab. 2007;5:415–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Levay EA, Tammer AH, Penman J, Kent S, Paolini AG. Calorie restriction at increasing levels leads to augmented concentrations of corticosterone and decreasing concentrations of testosterone in rats. Nutr Res. 2010;30:366–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hamrick MW, Pennington C, Newton D, Xie D, Isales C. Leptin deficiency produces contrasting phenotypes in bones of the limb and spine. Bone. 2004;34:376–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Thompson NM, Gill DA, Davies R, et al. Ghrelin and des-octanoyl ghrelin promote adipogenesis directly in vivo by a mechanism independent of the type 1a growth hormone secretagogue receptor. Endocrinology. 2004;145:234–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bredella MA, Torriani M, Ghomi RH, et al. Vertebral bone marrow fat is positively associated with visceral fat and inversely associated with IGF-1 in obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2011;19:49–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li GW, Xu Z, Chen QW, Chang SX, Tian YN, Fan JZ. The temporal characterization of marrow lipids and adipocytes in a rabbit model of glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Skeletal Radiol. 2013;42:1235–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Thomas T., Gori F., Khosla S., Jensen M. D., Burguera B., Riggs B. L. Leptin acts on human marrow stromal cells to enhance differentiation to osteoblasts and to inhibit differentiation to adipocytes. Endocrinology. 1999;140:1630–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Scheller EL, Song J, Dishowitz MI, Soki FN, Hankenson KD, Krebsbach PH. Leptin functions peripherally to regulate differentiation of mesenchymal progenitor cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:1071–1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hamrick MW, Della-Fera MA, Choi YH, Pennington C, Hartzell D, Baile CA. Leptin treatment induces loss of bone marrow adipocytes and increases bone formation in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Motyl KJ, McCabe LR. Leptin treatment prevents type I diabetic marrow adiposity but not bone loss in mice. J Cell Physiol. 2009;218:376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamrick MW, Della Fera MA, Choi YH, Hartzell D, Pennington C, Baile CA. Injections of leptin into rat ventromedial hypothalamus increase adipocyte apoptosis in peripheral fat and in bone marrow. Cell Tissue Res. 2007;327:133–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Takeda S, Elefteriou F, Levasseur R, et al. Leptin regulates bone formation via the sympathetic nervous system. Cell. 2002;111:305–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fazeli PK, Bredella MA, Misra M, et al. Preadipocyte factor-1 is associated with marrow adiposity and bone mineral density in women with anorexia nervosa. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:407–413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Harten S, Cardoso LA. Feed restriction and genetic selection on the expression and activity of metabolism regulatory enzymes in rabbits. Animal. 2010;4:1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Almeida AM, van Harten S, Campos A, Coelho AV, Cardoso LA. The effect of weight loss on protein profiles of gastrocnemius muscle in rabbits: a study using 1D electrophoresis and peptide mass fingerprinting. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl). 2010;94:174–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cawthorn WP, Bree AJ, Yao Y, et al. Wnt6, Wnt10a and Wnt10b inhibit adipogenesis and stimulate osteoblastogenesis through a β-catenin-dependent mechanism. Bone. 2012;50:477–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Du B, Cawthorn WP, Su A, et al. The transcription factor paired-related homeobox 1 (Prrx1) inhibits adipogenesis by activating transforming growth factor-β (TGFβ) signaling. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:3036–3047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Parlee SD, Lentz SI, Mori H, MacDougald OA. Quantifying size and number of adipocytes in adipose tissue. Methods Enzymol. 2014;537:93–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scheller EL, Doucette CR, Learman BS, et al. Region-specific variation in the properties of skeletal adipocytes reveals regulated and constitutive marrow adipose tissues. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. MacDougald OA, Hwang CS, Fan H, Lane MD. Regulated expression of the obese gene product (leptin) in white adipose tissue and 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9034–9037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Saladin R, De Vos P, Guerre-Millo M, et al. Transient increase in obese gene expression after food intake or insulin administration. Nature. 1995;377:527–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Zhang Y, Matheny M, Zolotukhin S, Tumer N, Scarpace PJ. Regulation of adiponectin and leptin gene expression in white and brown adipose tissues: influence of β3-adrenergic agonists, retinoic acid, leptin and fasting. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1584:115–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Arvidsson E, Viguerie N, Andersson I, Verdich C, Langin D, Arner P. Effects of different hypocaloric diets on protein secretion from adipose tissue of obese women. Diabetes. 2004;53:1966–1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Combs TP, Berg AH, Rajala MW, et al. Sexual differentiation, pregnancy, calorie restriction, and aging affect the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin. Diabetes. 2003;52:268–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Garaulet M, Viguerie N, Porubsky S, et al. Adiponectin gene expression and plasma values in obese women during very-low-calorie diet. Relationship with cardiovascular risk factors and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:756–760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Behre CJ, Gummesson A, Jernås M, et al. Dissociation between adipose tissue expression and serum levels of adiponectin during and after diet-induced weight loss in obese subjects with and without the metabolic syndrome. Metabolism. 2007;56:1022–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Qiang L, Wang H, Farmer SR. Adiponectin secretion is regulated by SIRT1 and the endoplasmic reticulum oxidoreductase Ero1-L α. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4698–4707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang ZV, Schraw TD, Kim JY, et al. Secretion of the adipocyte-specific secretory protein adiponectin critically depends on thiol-mediated protein retention. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3716–3731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Carson BP, Del Bas JM, Moreno-Navarrete JM, Fernandez-Real JM, Mora S. The rab11 effector protein FIP1 regulates adiponectin trafficking and secretion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kovacova Z, Vitkova M, Kovacikova M, et al. Secretion of adiponectin multimeric complexes from adipose tissue explants is not modified by very low calorie diet. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:585–592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoneda M, Iwasaki T, Fujita K, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia plays a crucial role in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus independent of visceral adipose tissue. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:S15–S21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhu M, Miura J, Lu LX, et al. Circulating adiponectin levels increase in rats on caloric restriction: the potential for insulin sensitization. Exp Gerontol. 2004;39:1049–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Varady KA, Tussing L, Bhutani S, Braunschweig CL. Degree of weight loss required to improve adipokine concentrations and decrease fat cell size in severely obese women. Metabolism. 2009;58:1096–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Nogueira LM, Lavigne JA, Chandramouli GV, Lui H, Barrett JC, Hursting SD. Dose-dependent effects of calorie restriction on gene expression, metabolism, and tumor progression are partially mediated by insulin-like growth factor-1. Cancer Med. 2012;1:275–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Judex S, Wohl GR, Wolff RB, Leng W, Gillis AM, Zernicke RF. Dietary fish oil supplementation adversely affects cortical bone morphology and biomechanics in growing rabbits. Calcif Tissue Int. 2000;66:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lawson EA, Klibanski A. Endocrine abnormalities in anorexia nervosa. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:407–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Moradi F, Mahdavi MRV, Ahmadiani A, et al. Social instability, food deprivation and food inequality can promote accumulation of lipofuscin and induced apoptosis in hepatocytes. World Applied Sci J. 2012;20:310–318. [Google Scholar]

- 62. Dietz AA, Steinberg B. Chemistry of bone marrow. VIII. Composition of rabbit bone marrow in inanition. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1953;45:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cohen P, Gardner FH. Effect of massive triamcinolone administration in blunting the erythropoietic response to phenylhydrazine hemolysis. J Lab Clin Med. 1965;65:88–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Vande Berg BC, Malghem J, Lecouvet FE, Lambert M, Maldague BE. Distribution of serouslike bone marrow changes in the lower limbs of patients with anorexia nervosa: predominant involvement of the distal extremities. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166:621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thouzeau C, Duchamp C, Handrich Y. Energy metabolism and body temperature of barn owls fasting in the cold. Physiol Biochem Zool. 1999;72:170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Varady KA, Allister CA, Roohk DJ, Hellerstein MK. Improvements in body fat distribution and circulating adiponectin by alternate-day fasting versus calorie restriction. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:188–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Fenton JI, Nuñez NP, Yakar S, Perkins SN, Hord NG, Hursting SD. Diet-induced adiposity alters the serum profile of inflammation in C57BL/6N mice as measured by antibody array. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Li X, Cope MB, Johnson MS, Smith DL, Jr, Nagy TR. Mild calorie restriction induces fat accumulation in female C57BL/6J mice. Obesity. 2010;18:456–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Hempenstall S, Picchio L, Mitchell SE, Speakman JR, Selman C. The impact of acute caloric restriction on the metabolic phenotype in male C57BL/6 and DBA/2 mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kurki E, Shi J, Martonen E, Finckenberg P, Mervaala E. Distinct effects of calorie restriction on adipose tissue cytokine and angiogenesis profiles in obese and lean mice. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9:64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Shi H, Strader AD, Woods SC, Seeley RJ. Sexually dimorphic responses to fat loss after caloric restriction or surgical lipectomy. American journal of physiology. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E316–E326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Magwere T, Chapman T, Partridge L. Sex differences in the effect of dietary restriction on life span and mortality rates in female and male Drosophila melanogaster. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:3–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Martin B, Pearson M, Kebejian L, et al. Sex-dependent metabolic, neuroendocrine, and cognitive responses to dietary energy restriction and excess. Endocrinology. 2007;148:4318–4333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Miersch C, Döring F. Sex differences in body composition, fat storage, and gene expression profile in Caenorhabditis elegans in response to dietary restriction. Physiol Genomics. 2013;45:539–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Leenen R, van der Kooy K, Droop A, et al. Visceral fat loss measured by magnetic resonance imaging in relation to changes in serum lipid levels of obese men and women. Arterioscler Thromb. 1993;13:487–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Wirth A, Steinmetz B. Gender differences in changes in subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat during weight reduction: an ultrasound study. Obes Res. 1998;6:393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Parker B, Noakes M, Luscombe N, Clifton P. Effect of a high-protein, high-monounsaturated fat weight loss diet on glycemic control and lipid levels in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:425–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Evans EM, Mojtahedi MC, Thorpe MP, Valentine RJ, Kris-Etherton PM, Layman DK. Effects of protein intake and gender on body composition changes: a randomized clinical weight loss trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9:55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Janssen I, Ross R. Effects of sex on the change in visceral, subcutaneous adipose tissue and skeletal muscle in response to weight loss. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:1035–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Ballor DL, Poehlman ET. Exercise-training enhances fat-free mass preservation during diet-induced weight loss: a meta-analytical finding. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1994;18:35–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span–from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Bartell SM, Rayalam S, Ambati S, et al. Central (ICV) leptin injection increases bone formation, bone mineral density, muscle mass, serum IGF-1, and the expression of osteogenic genes in leptin-deficient ob/ob mice. J Bone Miner Res. 2011;26:1710–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Ambati S, Li Q, Rayalam S, et al. Central leptin versus ghrelin: effects on bone marrow adiposity and gene expression. Endocrine. 2010;37:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL. 20 years of leptin: role of leptin in energy homeostasis in humans. J Endocrinol. 2014;223:T83–T96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ainslie DA, Morris MJ, Wittert G, Turnbull H, Proietto J, Thorburn AW. Estrogen deficiency causes central leptin insensitivity and increased hypothalamic neuropeptide Y. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25:1680–1688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sharma N, Castorena CM, Cartee GD. Greater insulin sensitivity in calorie restricted rats occurs with unaltered circulating levels of several important myokines and cytokines. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2012;9:90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Daoud NM, Mahrous KF, Ezzo OH. Feed restriction as a biostimulant of the production of oocyte, their quality and GDF-9 gene expression in rabbit oocytes. Anim Reprod Sci. 2012;136:121–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Villareal DT, Fontana L, Das SK, et al. Effect of two-year caloric restriction on bone metabolism and bone mineral density in non-obese younger adults: a randomized clinical trial. J Bone Miner Res. Published online ahead of print August 31, 2015. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Trubowitz S, Bathija A. Cell size and plamitate-1–14c turnover of rabbit marrow fat. Blood. 1977;49:599–605. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Gimble JM, Robinson CE, Wu X, Kelly KA. The function of adipocytes in the bone marrow stroma: an update. Bone. 1996;19:421–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Maurin AC, Chavassieux PM, Frappart L, Delmas PD, Serre CM, Meunier PJ. Influence of mature adipocytes on osteoblast proliferation in human primary cocultures. Bone. 2000;26:485–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Nuttall ME, Gimble JM. Is there a therapeutic opportunity to either prevent or treat osteopenic disorders by inhibiting marrow adipogenesis? Bone. 2000;27:177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Liu LF, Shen WJ, Zhang ZH, Wang LJ, Kraemer FB. Adipocytes decrease Runx2 expression in osteoblastic cells: roles of PPARγ and adiponectin. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:837–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Schwartz AV, Sigurdsson S, Hue TF, et al. Vertebral bone marrow fat associated with lower trabecular BMD and prevalent vertebral fracture in older adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2294–2300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Scheller EL, Rosen CJ. What's the matter with MAT? Marrow adipose tissue, metabolism, and skeletal health. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2014;1311:14–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Rosen CJ, Ackert-Bicknell C, Rodriguez JP, Pino AM. Marrow fat and the bone microenvironment: developmental, functional, and pathological implications. Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 2009;19:109–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Botolin S, McCabe LR. Inhibition of PPARγ prevents type I diabetic bone marrow adiposity but not bone loss. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:967–976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Iwaniec UT, Turner RT. Failure to generate bone marrow adipocytes does not protect mice from ovariectomy-induced osteopenia. Bone. 2013;53:145–153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Misra M, Klibanski A. Anorexia nervosa and osteoporosis. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2006;7:91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]