Abstract

Purpose

Autosomal recessive non-syndromic deafness (ARNSD) is characterized by a high degree of genetic heterogeneity with reported mutations in 58 different genes. This study was designed to detect deafness causing variants in a multiethnic cohort with ARNSD by using whole-exome sequencing (WES).

Methods

After excluding mutations in the most common gene, GJB2, we performed WES in 160 multiplex families with ARNSD from Turkey, Iran, Mexico, Ecuador and Puerto Rico to screen for mutations in all known ARNSD genes.

Results

We detected ARNSD-causing variants in 90 (56%) families, 54% of which had not been previously reported. Identified mutations were located in 31 known ARNSD genes. The most common genes with mutations were MYO15A (13%), MYO7A (11%), SLC26A4 (10%), TMPRSS3 (9%), TMC1 (8%), ILDR1 (6%) and CDH23 (4%). Nine mutations were detected in multiple families with shared haplotypes suggesting founder effects.

Conclusion

We report on a large multiethnic cohort with ARNSD in which comprehensive analysis of all known ARNSD genes identifies causative DNA variants in 56% of the families. In the remaining families, WES allows us to search for causative variants in novel genes, thus improving our ability to explain the underlying etiology in more families.

Keywords: Autosomal Recessive, Deafness, Exome, Next-Generation Sequencing

Introduction

Deafness is a global public health concern which affects 1 to 3 per 1,000 newborns.1 In more than half of the cases with congenital or prelingual deafness, the cause is genetic and most demonstrate an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern.1 Mutations in 58 different genes have been reported to cause autosomal recessive non-syndromic deafness (ARNSD) (http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/).

Except for one relatively common gene, GJB2 (MIM 121011), most reported mutations are present in only a single or a few families.2 Whole-exome sequencing (WES) allows resequencing of nearly all exons of the protein-coding genes in the genome.3 A growing number of research and clinical diagnostic laboratories are successfully using WES for gene/variant identification, owing to its comprehensive analysis advantages.4,5 In this study, we present the results of WES in a large multiethnic cohort consisting of 160 families with ARNSD that were negative for GJB2 mutations.

Material and Methods

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board (USA), Ankara University Medical School Ethics Committee (Turkey), Growth and Development Research Ethics Committee (Iran), Bioethics Committee of FFAA (HE-1) in Quito (Ecuador) and the Ethics Committee of National Institute of Rehabilitation (Mexico). A signed informed consent form was obtained from each participant or, in the case of a minor, from parents.

Subjects

We included 160 families with at least two members with nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss with a pedigree structure suggestive of autosomal recessive inheritance (affected siblings born to unaffected parents with or without parental consanguinity) and GJB2 mutations were negative. Hearing loss was congenital or prelingual onset with a severity ranging from mild to profound. One hundred and one families from Turkey, fifty-four from Iran, two from Mexico, two from Ecuador and one from Puerto Rico were included. Sensorineural hearing loss was diagnosed via standard audiometry in a sound-proof room according to standard clinical practice. Clinical evaluation of all affected individuals by a geneticist and an otolaryngologist included a thorough physical examination, otoscopy, and ophthalmoscopy. Tandem walking and the Romberg test were used for initial vestibular evaluation with more detailed tests if needed based on symptoms and findings. Laboratory investigation included but was not limited to an EKG, urinalysis, and, when available, a high resolution CT scan of the temporal bone or an MRI to identify inner ear anomalies. DNA was extracted from peripheral leukocytes of each member of the family by standard protocols.

Whole-Exome Sequencing

Agilent SureSelect Human All Exon 50 Mb versions 3, 4, and 5 (Agilent Technologies Santa Clara, CA) were used for in-solution enrichment of coding exons and flanking intronic sequences following the manufacturer's standard protocol. The enriched DNA samples were subjected to standard sample preparation for the HiSeq 2000 instrument (Illumina San Diego, CA). The Illumina CASAVA v1.8 pipeline was used to produce 99 bp sequence reads. BWA6 was used to align sequence reads to the human reference genome (hg19) and variants were called using the GATK (https://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/) software package.7 All single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and insertion/deletions (INDELs) were submitted to SeattleSeq137 for further characterization and annotation. Sanger sequencing was used for confirmation and segregation of the variants in each family.

Bioinformatics Analysis

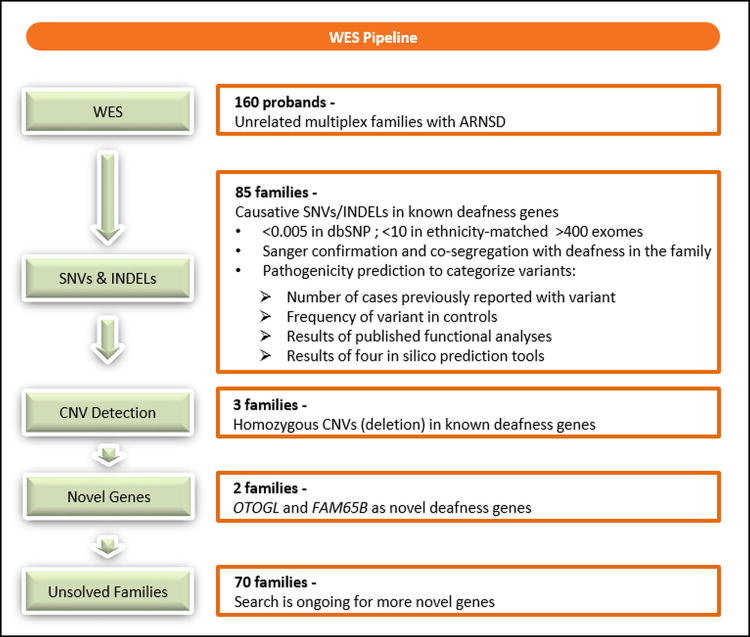

We analyzed WES data using our in house tool (https://genomics.med.miami.edu). Our workflow is seen in Figure 1. The analysis started with QC checks including the coverage and average read depth of targeted regions, numbers of variants in different categories, and quality scores. All variants were annotated and categorized into known and novel variants. As previously recommended, we filtered variants based on minor allele frequency of <0.005 in dbSNP141.8 We also filtered out variants that are present in >10 samples in our internal database of >3,000 exomes from European, Asian, and American ancestries that includes Turkish, Iranian, Mexican, Ecuadorian, and Puerto Rican samples (Figure 1). Autosomal recessive inheritance with both homozygous and compound heterozygous inheritance models, and a genotype quality (GQ) score >35 for the variant quality were chosen. Missense, nonsense, splice site, in-frame INDEL and frame-shift INDELs in the known ARNSD genes (supplementary data) were selected. Missense variants that remained after these filters were later analyzed for presence in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) (www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk) and having a pathogenic prediction score at least in two of the following tools: PolyPhen29, SIFT10, MutationAssessor11, and MutationTaster12. Finally, we used CoNIFER13 (Copy Number Inference From Exome Reads) and XHMM14 (eXome-Hidden Markov Model) to detect CNVs.15 After this filtering, only those variants co-segregated with the phenotype in the entire family was considered pathogenic.

Fig.1. Overall workflow of our WES pipeline.

Results

On average, each exome had 99%, 95% and 88% of mappable bases of the Gencode defined exome represented by coverage of 1X, 5X and 10X reads, respectively. Average coverage of the mappable bases for the 58 known ARNSD genes (exons and the first and last 20 bps of introns) were 99%, 95%, 87% for the 1X, 5X, 10X reads, respectively.

We detected pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants that can explain ARNSD in 90 (56%) families. All identified variants co-segregated with deafness as an autosomal recesive trait. 54% of the mutations were not previously reported in HGMD. Mutations were identified in 31 ARNSD genes. The genes with mutations identified in at least three families are MYO15A (MIM 602666) (13%), MYO7A (MIM 276903) (11%), SLC26A4 (MIM 605646) (10%), TMPRSS3 (MIM 605551) (9%), TMC1 (MIM 606706) (8%), ILDR1 (MIM 609739) (6%), CDH23 (MIM 605516) (4%), OTOF (MIM 603681) (4%), PCDH15 (MIM 605514) (3%), and TMIE (MIM 607723) (3%). During the course of this study we reported mutations in OTOGL (MIM 614925) and FAM65B (MIM 611410) as novel causes of ARNSD16,17 (Figure 1)(Table 1).

Table 1. Mutations identified in known ARNSD genes*.

| Family ID | Country of origin | Genotype | cDNA | Protein | NM Transcript | Gene | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 543 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.4441T>C | p.S1481P | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | (Cengiz 2010)23 |

| 724 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.4652C>A | p.A1551D | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 765 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.4273C>T | p.Q1425X | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 723 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.8307_8309delGGA | p.E2770del | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| 795 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5808_5814delCCGTGGC | p.R1937TfsX10 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | (Cengiz 2010)23 |

| 793 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5808_5814delCCGTGGC | p.R1937TfsX10 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | (Cengiz 2010)23 |

| 1209 | Puerto Rico | Heterozygous | c.7226delC | p.P2409QfsX8 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.9620G>A | p.R3207H | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel | ||

| 1083 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5183T>C | p.L1728P | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| 1332 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.10361delT | p.V3454GfsX5 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| 489 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5286_5287delTC | p.R1763AfsX45 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| 1023 | Iran | Homozygous | c.8638_8641delCCTG | p.P2880RfsX19 | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| 862 | Turkey | Heterozygous | c.7894G>T | p.V2632L | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.5133+1G>A | splice | NM_016239.3 | MYO15A | Novel | ||

| 974 | Iran | Homozygous | c.6487G>A | p.G2163S | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Janecke 1999)24 |

| 1391 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.6487G>A | p.G2163S | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Janecke 1999)24 |

| 435 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.3935T>C | p.L1312P | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel |

| 472 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1556G>T | p.G519V | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel |

| 1370 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.722G>A | p.R241H | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Cremers 2007)25 |

| 432 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5362_5363delAG | p.R1788DfsX13 | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel |

| 637 | Turkey | Heterozygous | c.5838delT | p.F1946LfsX24 | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.5573T>C | p.L1858P | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Bharadwaj 2000)26 | ||

| 996 | Iran | Homozygous | c.5785C>T | p.Q1929X | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel |

| 1019 | Iran | Homozygous | c.1708C>T | p.R570X | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Yoshimura 2014)27 |

| 1404 | Turkey | Heterozygous | c.1708C>T | p.R570X | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | (Yoshimura 2014)27 |

| Heterozygous | c.6025G>A | p.A2009T | NM_000260.3 | MYO7A | Novel | ||

| 786 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1001G>T | p.G334V | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Landa 2013)28 |

| 634 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1001G>T | p.G334V | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Landa 2013)28 |

| 1418 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1061T>C | p.F354S | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Blons 2004)29 |

| 238 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1226G>A | p.R409H | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Van hauwe 1998)30 |

| 973 | Iran | Homozygous | c.1334T>G | p.L445W | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Van hauwe 1998)30 |

| 905 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2168A>G | p.H723R | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Van hauwe 1998)30 |

| 1417 | Turkey | Heterozygous | c.665G>A | p.G222D | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.1198delT | p.C400VfsX32 | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | Novel | ||

| 1346 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.919-2A>G | splice | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | (Coucke 1999)31 |

| 1321 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1198delT | p.C400VfsX32 | NM_000441.1 | SLC26A4 | Novel |

| 395 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.36dupC | p.F13LfsX10 | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 777 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.913A>T | p.I305F | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 674 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.271C>T | p.R91X | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 629 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.399G>C | p.W133C | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 1368 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1126G>A | p.G376S | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 1410 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.436G>A | p.G146S | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 910 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.616G>T | p.A206S | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 633 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.616G>T | p.A206S | NM_024022.2 | TMPRSS3 | Novel |

| 52 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1589_1590CT | p.S530X | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | (Hildebrand 2010)32 |

| 123 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1080_1084delGATCA | p.R362PfsX6 | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | Novel |

| 662 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2050G>A | p.D684N | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | Novel |

| 1268 | Ecuador | Heterozygous | c.1718T>A | p.I573N | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.2130-1delG | splice | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | Novel | ||

| 911 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1534C>T | p.R512X | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | (Kurima 2002)33 |

| 490 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1959C>G | p.Y653X | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | Novel |

| 393 | Turkey | Heterozygous | c.63+2T>A | splice | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | (Duman 2011)18 |

| Heterozygous | c.236+1G>A | splice | NM_138691.2 | TMC1 | (Duman 2011)18 | ||

| 988 | Iran | Homozygous | c.3215C>A | p.A1072D | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | (Duman 2011)18 |

| 1165 | Mexico | Heterozygous | c.2959G>A | p.D987N | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.3628C>T | p.Q1210X | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | Novel | ||

| 1015 | Iran | Homozygous | c.5851G>A | p.D1951N | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | Novel |

| 1032 | Iran | Heterozygous | c.7822C>T | p.R2608C | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | Novel |

| Heterozygous | c.8120C>T | p.P2707L | NM_022124.5 | CDH23 | Novel | ||

| 968 | Iran | Homozygous | c.820C>T | p.Q274X | NM_001199799.1 | ILDR1 | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 800 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.942C>A | p.C314X | NM_001199799.1 | ILDR1 | Novel |

| 799 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.942C>A | p.C314X | NM_001199799.1 | ILDR1 | Novel |

| 782 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.942C>A | p.C314X | NM_001199799.1 | ILDR1 | Novel |

| 969 | Iran | Homozygous | c.82delG | p.V28SfsX31 | NM_001199799.1 | ILDR1 | Novel |

| 1297 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5431A>T | p.K1811X | NM_194248.2 | OTOF | (Romanos 2009)34 |

| 98 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.5431A>T | p.K1811X | NM_194248.2 | OTOF | (Romanos 2009)34 |

| 1398 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.3679C>T | p.R1227X | NM_194248.2 | OTOF | Novel |

| 909 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.765G>C | p.Q255H | NM_194248.2 | OTOF | (Rodriguez 2008)35 |

| 725 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.3918T>G | p.C1306W | NM_033056.3 | PCDH15 | Novel |

| 1238 | Turkey | Homozygous | CNV | CNV | NM_033056.3 | PCDH15 | Novel |

| 1044 | Iran | Homozygous | c.3101G>A | p.R1034H | NM_033056.3 | PCDH15 | Novel |

| 1369 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.250C>T | p.R84W | NM_147196.2 | TMIE | (Naz 2002)36 |

| 1354 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.250C>T | p.R84W | NM_147196.2 | TMIE | (Naz 2002)36 |

| 1402 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.250C>T | p.R84W | NM_147196.2 | TMIE | (Naz 2002)36 |

| 1239 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.490-1G>T | splice | NM_016366.2 | CABP2 | Novel |

| 1366 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1018G>T | p.E340X | NM_004452.3 | ESRRB | Novel |

| 1372 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1018G>T | p.E340X | NM_004452.3 | ESRRB | Novel |

| 794 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.508C>A | p.H170N | NM_133261.2 | GIPC3 | Novel |

| 1356 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.508C>A | p.H170N | NM_133261.2 | GIPC3 | Novel |

| 182 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.4480C>T | p.R1494X | NM_144612.6 | LOXHD1 | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 779 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2863G>T | p.E955X | NM_144612.6 | LOXHD1 | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 303 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.628A>T | p.K210X | NM_005709.3 | USH1C | Novel |

| 994 | Iran | Homozygous | c.876+2delTA | splice | NM_005709.3 | USH1C | Novel |

| 661 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.330T>A | p.Y110X | NM_006383.3 | CIB2 | Novel |

| 262 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2662C>A | p.P888T | NM_080680.2 | COL11A2 | (Chakchouk 2015)37 |

| 448 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.499C>T | p.R167X | NM_001042702.3 | DFNB59 | (Collin 2007)38 |

| 908 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.102-1G>A | splice | NM_014722.2 | FAM65B | (Diaz-Horta 2014)17 |

| 1289 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2956A>T | p.K986X | NM_032119.3 | GPR98 | Novel |

| 820 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.79C>T | p.R27X | NM_001080476.2 | GRXCR1 | Novel |

| 67 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1498C>T | p.R500X | NM_001038603.2 | MARVELD2 | (Riazuddin 2006)39 |

| 1364 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1015C>T | p.R339W | NM_004999.3 | MYO6 | (Yang 2013)40 |

| 63 | Turkey | Homozygous | CNV | CNV | NM_144672.3 | OTOA | (Bademci 2014)15 |

| 338 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1430delT | p.V477EfsX25 | NM_173591.3 | OTOGL | (Yariz 2012)16 |

| 1294 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.1108C>T | p.R370X | NM_002906.3 | RDX | Novel |

| 850 | Turkey | Homozygous | CNV | CNV | NM_153700.2 | STRC | (Bademci 2014)15 |

| 1035 | Iran | Homozygous | c.5210A>G | p.Y1737C | NM_005422.2 | TECTA | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 7 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.705_709dupCCTGC | p.R237PfsX215 | NM_001128228.2 | TPRN | Novel |

| 23 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.2335_2336delAG | p.R785SfsX50 | NM_001039141.2 | TRIOBP | (Diaz-Horta 2012)4 |

| 5 | Turkey | Homozygous | c.387_388insC | p.K130QfsX5 | NM_173477.2 | USH1G | Novel |

Families with compound heterozygous mutations are italicized.

Discussion

Identifying causative variants in ARNSD is challenging because of (1) the extreme genetic heterogeneity of ARNSD; (2) the presence of different categories of genetic variants such as SNVs, INDELs and CNVs; (3) the presence of a high proportion of non-recurrent mutations and (4) the variability in mutation frequencies in individual ARNSD genes across ethnicities.18 Consequently, we performed a comprehensive analysis to detect pathogenic SNVs, INDELs and CNVs in the ARNSD genes.

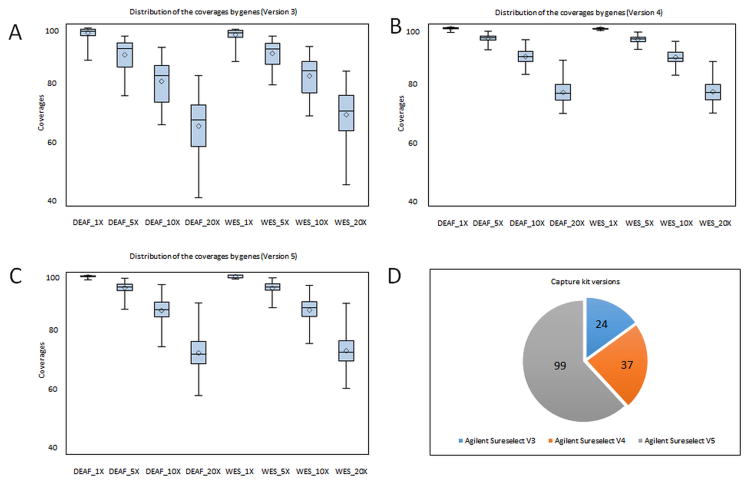

Targeted resequencing allows identification of mutations in the interested gene sets. Recent studies pioneered by Shearer et al. have shown the effectiveness of the targeted resequencing of deafness genes.8,19 An advantage of the targeted resequencing over WES is having better coverage with higher depth and significantly lowered costs, which is suitable for clinical diagnostic labs. However, a main limitation of the targeted sequencing is the need for revalidation of the panel after adding each new gene. In contrast, many laboratories around the world offer WES as a diagnostic tool requiring validation only when a new WES version is introduced. Our analysis using three different versions of an exome capture kit during the four year period shows that the depth of coverage of WES has improved to reliably identify most mutations in known ARNSD genes (Figure 2) (Table S1 and Table S4). Recently developed WES approaches provide more coverage for genes that are known to cause Mendelian disease. They are expected to cover deafness genes more efficiently. In addition, adding in baits to improve coverage over poorly covered regions may be considered if a better coverage is desired. It was recently shown via targeted sequencing that CNVs are a common cause of deafness.20 While CNV analysis of the WES data is being still optimized for clinical usage, we integrated two currently available tools, XHMM and CoNIFER into our WES analysis pipeline and identified large OTOA (MIM 607038), STRC (MIM 606440) and PCDH15 (exon 27-28) homozygous deletions in our cohort, supporting a significant role of CNVs to in deafness etiology.

Fig.2.

Overview of coverage of 58 known ARNSD genes according to 3 different versions (Version 3=V3, Version 4=V4 and Version 5=V5) of the exome enrichment kit (A,B,C). Numbers of samples studied with different capture kits (D).

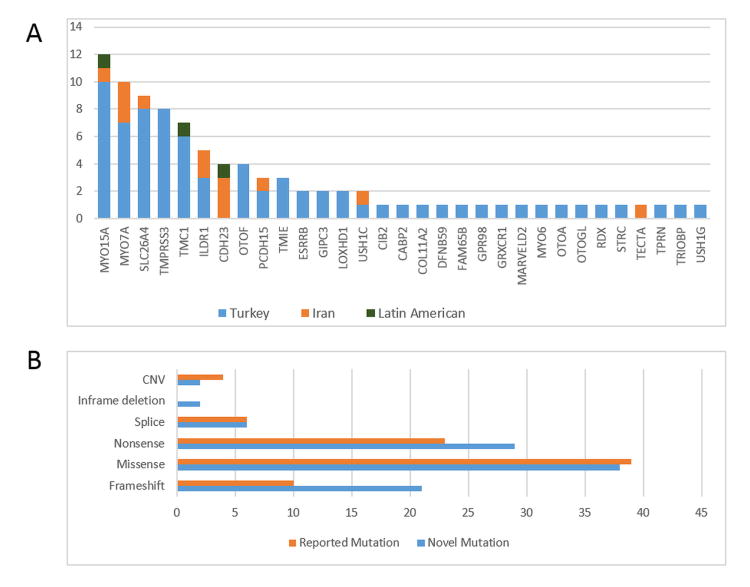

In this study after excluding GJB2 mutations we detected pathogenic variants in the known ARNSD genes in 56% of the studied families. The advantage of this study is to have large multiplex autosomal recessive families (including affected and unaffected children) that can be tested for co-segregation of all variants. While we identified more novel variants than those reported in Table 1 through WES, only those variants co-segregated in the family with deafness were considered pathogenic. Similarly heterozygous variants didn't explain the phenotype since they did not co-segregate with deafness and were not included. WES facilitates the cataloguing of mutations in different populations. Population characteristics such as the rate of consanguineous marriages may affect the distribution of deafness mutations in different populations. As expected, the vast majority of Turkish and Iranian probands from consanguineous marriages are homozygous for the pathogenic variants (Table 2). However, there is a marked difference between the rates of solved families in Turkey (73%) vs. Iran (24%) (Figure 3). As seen in figure 3, the distribution of genes is also different between the two countries. In our study, the top five genes explain 39 out of 101 families (39%) in Turkey, while only 10 out of 54 families (19%) in Iran. Moreover, our analysis of the WES data in the unsolved Iranian families shows that there are no common mutations in genes that are not known to be deafness genes (data not shown). Unless there are common mutations in regions that are not well covered by WES, our data suggest that many rare genes are responsible for the majority of hereditary deafness in the Iranian cohort. It is likely that there are undetected rare variants specific to certain ethnicities in Iran.21 Another advantage of WES is to allow surveying of mutations for founder effects. We detected TMIE c.250C>T (p.R84W) in three unrelated Turkish families, which all shared a flanking haplotype as noted previously.22 Furthermore MYO15A, MYO7A, SLC26A4, TMPRSS3, ILDR1, OTOF, ESRRB (MIM 602167) and GIPC3 (MIM 608792) genes had recurrent mutations with shared haplotypes indicating founder effects (Table S2).

Table 2. Overview of mutation detection and parental consanguinity.

| Countries | Number of Families | Reported Parental Consanguinity | Number of Homozygous Probands (consanguineous) | Number of Compound Heterozygous Probands (consanguineous) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 101 | 82 | 67 (59) | 5 (2) |

| Iran | 54 | 31 | 12 (10) | 1 (1) |

| Ecuador | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) |

| Mexico | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) |

| Puerto Rico | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0) |

Fig.3.

Distribution of causative DNA variants in known ARNSD genes according to the family origin (A) and variant categories (B).

There is no correlation between the size of transcript and number of mutant alleles (Table S3). There may be some deafness genes that are more prone to have mutations. Founder effects appear to play a role because some small genes such as TMIE, ESRRB, and GIPC3 ranked high in mutation frequency because of founder mutations. Some discrepancy between the size of a gene and number of mutations can be explained by the fact that only certain mutations cause nonsyndromic deafness for some genes. For instance, CDH23, PCDH15, MYO7A are big genes but many mutations in those genes cause Usher syndrome (MIM 276900) instead of ARNSD. An interesting example is TMC1 that ranks the 20th based on size but the 5th for mutation frequency. Nonsyndromic deafness is the only phenotype caused by TMC1 mutations and none of the TMC1 mutations are recurrent in our cohort. These may suggest that TMC1 is relatively more prone to have de novo mutations or it is a highly conserved gene and its variants are rarely tolerated.

In conclusion, WES is a an effective tool for identifying pathogenic SNVs, INDELs and CNVs simultaneously in ARNSD genes and provides further analysis of the unsolved families for novel gene discovery. Identification of two novel ARNSD genes16,17 during the course of this study testifies its power.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the participating families.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant R01DC009645 to M.T.

Footnotes

Author Disclosure Statement: Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest to report.

Supplementary Material:Supplementary information is available at the Genetics in Medicine website

References

- 1.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening--a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2151–2164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duman D, Tekin M. Autosomal recessive nonsyndromic deafness genes: a review. Front Biosci (Landmark Ed) 2012;17:2213–2236. doi: 10.2741/4046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ng SB, Turner EH, Robertson PD, et al. Targeted capture and massively parallel sequencing of 12 human exomes. Nature. 2009;461:272–276. doi: 10.1038/nature08250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Diaz-Horta O, Duman D, Foster J, 2nd, et al. Whole-exome sequencing efficiently detects rare mutations in autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. PLoS One. 2012;7:e50628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Atik T, Bademci G, Diaz-Horta O, Blanton S, Tekin M. Whole-exome sequencing and its impact in hereditary hearing loss. Genet Res (Camb) 2015;97:e4. doi: 10.1017/S001667231500004X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shearer AE, Eppsteiner RW, Booth KT, et al. Utilizing ethnic-specific differences in minor allele frequency to recategorize reported pathogenic deafness variants. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:248–249. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0410-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–1081. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reva B, Antipin Y, Sander C. Predicting the functional impact of protein mutations: application to cancer genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:e118. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11:361–362. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krumm N, Sudmant PH, Ko A, et al. Copy number variation detection and genotyping from exome sequence data. Genome Res. 2012;22:1525–1532. doi: 10.1101/gr.138115.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fromer M, Moran JL, Chambert K, et al. Discovery and statistical genotyping of copy-number variation from whole-exome sequencing depth. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:597–607. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bademci G, Diaz-Horta O, Guo S, et al. Identification of copy number variants through whole-exome sequencing in autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing loss. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2014;18:658–661. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2014.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yariz KO, Duman D, Seco CZ, et al. Mutations in OTOGL, encoding the inner ear protein otogelin-like, cause moderate sensorineural hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:872–882. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diaz-Horta O, Subasioglu-Uzak A, Grati M, et al. FAM65B is a membrane-associated protein of hair cell stereocilia required for hearing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:9864–9868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401950111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duman D, Sirmaci A, Cengiz FB, Ozdag H, Tekin M. Screening of 38 genes identifies mutations in 62% of families with nonsyndromic deafness in Turkey. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2011;15:29–33. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shearer AE, DeLuca AP, Hildebrand MS, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss using massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:21104–21109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012989107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shearer AE, Kolbe DL, Azaiez H, et al. Copy number variants are a common cause of non-syndromic hearing loss. Genome Med. 2014;6:37. doi: 10.1186/gm554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mahdieh N, Rabbani B, Wiley S, Akbari MT, Zeinali S. Genetic causes of nonsyndromic hearing loss in Iran in comparison with other populations. J Hum Genet. 2010;55:639–648. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2010.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sirmaci A, Ozturkmen-Akay H, Erbek S, et al. A founder TMIE mutation is a frequent cause of hearing loss in southeastern Anatolia. Clin Genet. 2009;75:562–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01183.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cengiz FB, Duman D, Sirmaci A, et al. Recurrent and private MYO15A mutations are associated with deafness in the Turkish population. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2010;14:543–550. doi: 10.1089/gtmb.2010.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Janecke AR, Meins M, Sadeghi M, et al. Twelve novel myosin VIIA mutations in 34 patients with Usher syndrome type I: confirmation of genetic heterogeneity. Hum Mutat. 1999;13:133–140. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1999)13:2<133::AID-HUMU5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cremers FP, Kimberling WJ, Kulm M, et al. Development of a genotyping microarray for Usher syndrome. J Med Genet. 2007;44:153–160. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2006.044784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bharadwaj AK, Kasztejna JP, Huq S, Berson EL, Dryja TP. Evaluation of the myosin VIIA gene and visual function in patients with Usher syndrome type I. Exp Eye Res. 2000;71:173–181. doi: 10.1006/exer.2000.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoshimura H, Iwasaki S, Nishio SY, et al. Massively parallel DNA sequencing facilitates diagnosis of patients with Usher syndrome type 1. PLoS One. 2014;9:e90688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Landa P, Differ AM, Rajput K, Jenkins L, Bitner-Glindzicz M. Lack of significant association between mutations of KCNJ10 or FOXI1 and SLC26A4 mutations in Pendred syndrome/enlarged vestibular aqueducts. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blons H, Feldmann D, Duval V, et al. Screening of SLC26A4 (PDS) gene in Pendred's syndrome: a large spectrum of mutations in France and phenotypic heterogeneity. Clin Genet. 2004;66:333–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Hauwe P, Everett LA, Coucke P, et al. Two frequent missense mutations in Pendred syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/hmg/7.7.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coucke PJ, Van Hauwe P, Everett LA, et al. Identification of two different mutations in the PDS gene in an inbred family with Pendred syndrome. J Med Genet. 1999;36:475–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hildebrand MS, Kahrizi K, Bromhead CJ, et al. Mutations in TMC1 are a common cause of DFNB7/11 hearing loss in the Iranian population. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119:830–835. doi: 10.1177/000348941011901207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurima K, Peters LM, Yang Y, et al. Dominant and recessive deafness caused by mutations of a novel gene, TMC1, required for cochlear hair-cell function. Nat Genet. 2002;30:277–284. doi: 10.1038/ng842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Romanos J, Kimura L, Favero ML, et al. Novel OTOF mutations in Brazilian patients with auditory neuropathy. J Hum Genet. 2009;54:382–385. doi: 10.1038/jhg.2009.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Ballesteros M, Reynoso R, Olarte M, et al. A multicenter study on the prevalence and spectrum of mutations in the otoferlin gene (OTOF) in subjects with nonsyndromic hearing impairment and auditory neuropathy. Hum Mutat. 2008;29:823–831. doi: 10.1002/humu.20708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naz S, Giguere CM, Kohrman DC, et al. Mutations in a novel gene, TMIE, are associated with hearing loss linked to the DFNB6 locus. Am J Hum Genet. 2002;71:632–636. doi: 10.1086/342193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakchouk I, Grati M, Bademci G, et al. Novel mutations confirm that COL11A2 is responsible for autosomal recessive non-syndromic hearing loss DFNB53. Mol Genet Genomics. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-0995-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Collin RW, Kalay E, Oostrik J, et al. Involvement of DFNB59 mutations in autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment. Hum Mutat. 2007;28:718–723. doi: 10.1002/humu.20510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Fanning AS, et al. Tricellulin is a tight-junction protein necessary for hearing. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:1040–1051. doi: 10.1086/510022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang T, Wei X, Chai Y, Li L, Wu H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:85. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-8-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.