Abstract

Objective

To determine whether there is an association between the geographic location of an applicant’s undergraduate school, medical school, and residency program among matched otolaryngology residency applicants.

Study Design

Observational.

Methods

Otolaryngology residency program applications to our institution from 2009 to 2013 were analyzed. The geographic location of each applicant’s undergraduate education and medical education were collected. Online public records were queried to determine the residency program location of matched applicants. Applicants who did not match or who attended medical school outside the US were excluded. Metro area, state, and region were determined according to United States Census Bureau definitions.

Results

From 2009-2013, 1,089 (78%) of 1,405 applicants who matched into otolaryngology residency applied to our institution. The number of subjects who attended medical school and residency in the same geographic region was 241 (22%) for metropolitan area, 305 (28%) for state, and 436 (40%) for region. There was no difference in geographic location retention by gender or couples match status of the subject. USMLE step 1 scores correlated with an increased likelihood of subjects staying within the same geographic region (p=0.03).

Conclusion

Most otolaryngology applicants leave their previous geographic area to attend residency. Based on these data, the authors recommend against giving weight to geography as a factor when inviting applicants to interview.

Keywords: Otolaryngology, Residency, Geography, Match

Introduction

Residency program directors and resident selection committees have the challenging task of recruiting the most well qualified applicants to their programs. With hundreds of qualified medical students applying for a limited number of positions within otolaryngology residency programs, difficult decisions must be made about which applicants to invite for interviews and where to rank applicants for the match. To help accomplish this important task, selection committees need to be aware of the program characteristics that influence an applicant’s rank list. Prior studies point towards academic factors as the leading characteristics that influence an applicant to rank a program highly. In surgical residencies these factors include amount of operative experience, diversity of operative cases, and resident satisfaction.1-3

One characteristic beyond the control of the selection committee is the geographic location of the program. Although applicants generally consider academic factors of primary importance in residency selection, surveys from the last several years across many specialties have demonstrated that applicants also consider geography when deciding where they would like to go for residency.3-7 One study noted that location is the third most important ranking criterion among otolaryngology applicants, whereas program directors believe that location is a less important factor.3

The authors theorize that when selection committees have to decide between two equally qualified applicants, they are biased towards choosing the applicant that is closer geographically.8 Although several studies have evaluated what factors applicants use to rank programs, no studies have analyzed the influence of geographic location on where an applicant matches. The purpose of this study is to determine whether there is an association between the geographic location of an applicant’s undergraduate school, medical school, and residency program among matched otolaryngology residency applicants.

Materials and Methods

Data Collection

Approval was obtained from the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board. This is an observational study of residency program applications to our institution from the 2009-2013 otolaryngology match cycles. The geographic location of each applicant’s undergraduate education and medical education were collected from ERAS applications. Applicant characteristics, such as gender, couples match status, and United States Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) step 1 score were also collected. Online public records were queried to determine the residency program location of matched applicants. Applicants who did not match or who attended medical school outside the US were excluded. Metro area, state, and region were determined according to United States Census Bureau definitions. National Residency Matching Program data was used to determine number of programs, their location, and number of resident positions per year.9

Statistical Analysis

Placement outcomes were modeled using logistic regression. All potential predictors were tested individually to exclude those with no statistically significant association with the outcome. The remaining predictors were entered into the model in a stepwise fashion to produce the final model. A significance level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

Results

Of the 1404 matched otolaryngology applicants from 2009-2013, there were 1089 (78%) that applied to our institution and met inclusion criteria for the study. The demographic characteristics of study participants are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Study Participants (2009-2013)

| Application Year | N | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 208 | 18.8 |

| 2010 | 206 | 18.6 |

| 2011 | 226 | 20.4 |

| 2012 | 222 | 20.0 |

| 2013 | 245 | 22.1 |

| Total | 1107 | 100 |

| Gender | N | Percent |

| Male | 725 | 65% |

| Female | 382 | 35% |

| Age | Mean | SD |

| 27 | 2.2 | |

| Couples | N | Percent |

| Yes | 86 | 8% |

| No | 1021 | 92% |

| USMLE step 1 Score | Mean | SD |

| 243 | 14 | |

| OTO Residency at Med School |

N | Percent |

| Yes | 967 | 87.4 |

| No | 140 | 12.6 |

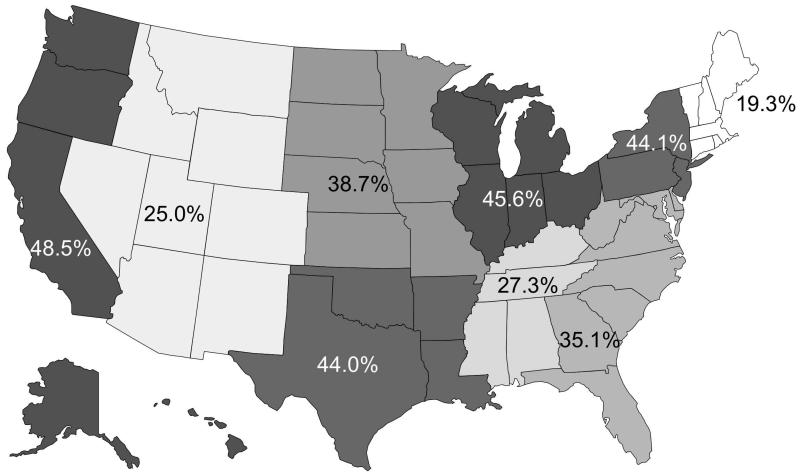

Forty percent (n=436) of study participants stayed within the same geographic region as their medical school for otolaryngology residency. A smaller percentage of subjects stayed within the same state (28%; n=305) or metropolitan area (22%; n=241) for residency. Retention rates of all subjects by region are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Participants Staying in the Same Region for Medical School and Otolaryngology Residency

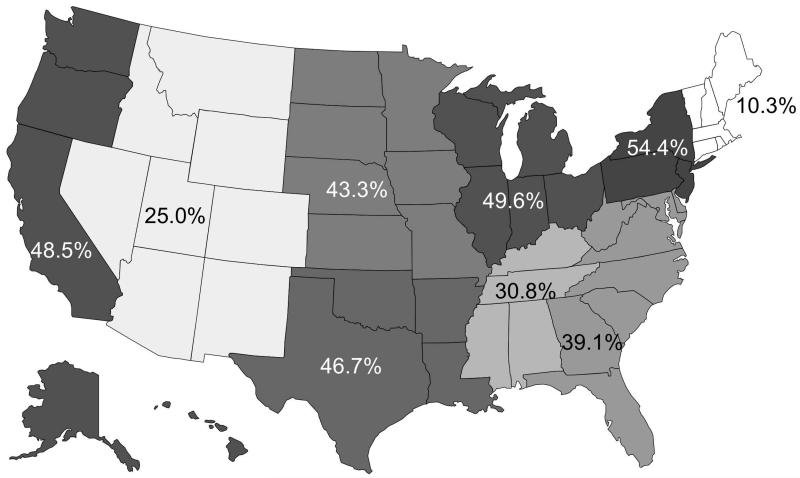

A number of subjects attended college and medical school in the same geographic area. Retention rates were increased overall within this subgroup, with only New England showing a decrease in retention. Retention rates for this subgroup were 44% (n=286/653) for region, 29% (n=151/524) for state, and 23% (n=49/215) for metropolitan area. Retention rates for subjects attending college and medical school in the same region are displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Participants in Same Region for College and Medical School that Stayed for Otolaryngology Residency

Despite regional differences, retention was universally low among subjects, with less than 50% of subjects in each geographic region staying for residency. When comparing participants who stayed in the same geographic region for medical school and residency versus those who relocated, there was no significant difference between groups when adjusted for gender (p=0.85) or couples match status (p=0.65).

We compared geographic retention to USMLE step 1 scores as a continuous scale with a best line of fit. When compared this way, higher step scores correlated to higher retention rates (from medical school to residency) within a geographic region, but the model was unreliable, with an R2 score of 0.003. We then compared groups of subjects by USMLE step 1 score greater than or less than 240. This score was chosen because it was the mean USMLE step 1 score for matched applicants in 2009. Subjects with a USMLE step 1 score greater than 240 were more likely to leave their medical school geographic region (p=0.002) for residency than subjects with a score less than 240. USMLE step 1 scores using the cut off score of 240 were did not affect the likelihood of staying within the same state (p=0.48) or metro area (p=0.76).

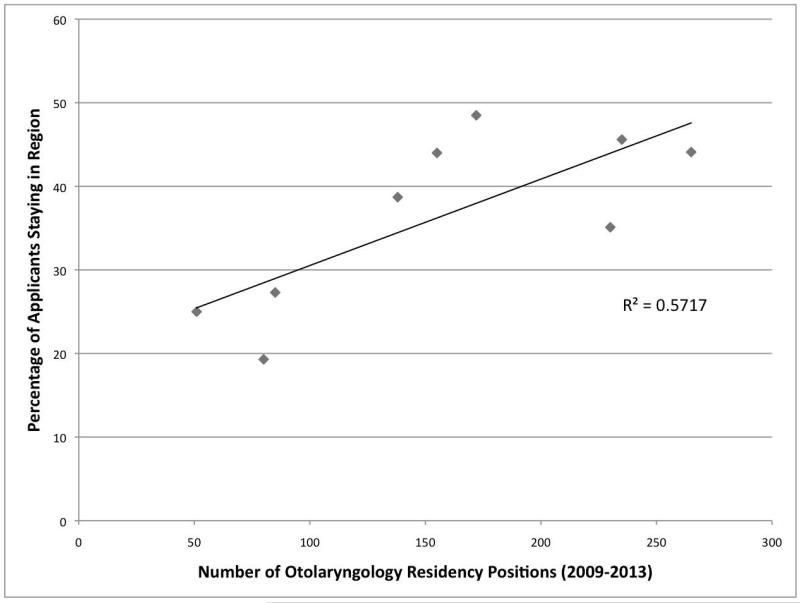

When comparing groups of subjects whose medical school either did or did not have an affiliated otolaryngology residency program, subjects coming from a medical school with a residency program were more likely to stay within the same metro area (p=<0.0001) or state (p=.002). In addition, geographic regions with more otolaryngology residency programs demonstrated a higher rate of applicant retention (p=0.04). The three regions with the lowest retention rates were New England (19.3%), Mountain (25.0%), and East South Central (30.8%), and these three regions also had the fewest number of residency positions. Table 2 displays the geographic distribution of US census regions and number of otolaryngology residency positions in each region. Figure 3 shows the relationship between number of otolaryngology residency positions and percentage of participants staying in each region.

Table 2.

2009-2013 US Census Regions and Number of Otolaryngology Residency Positions

| US Census Division |

States Included | # OTO Programs |

# Positions | % Staying |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New England | CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT |

7 | 80 | 19.3 |

| Mid-Atlantic | NJ, NY, PA | 17 | 265 | 44.1 |

| East North Central |

IL, IN, MI, OH, WI |

16 | 232 | 45.6 |

| West North Central |

IA, KS, MN, MO, ND, NE, SD |

8 | 138 | 38.7 |

| South Atlantic | DC, DE, FL, GA, MD, NC, SC, VA, WV |

17 | 230 | 35.1 |

| East South Central |

AL, KY, MS, TN | 6 | 85 | 27.3 |

| West South Central |

AR, LA, OK, TX | 11 | 151 | 44 |

| Mountain | AZ, CO, ID, MT, NM, NV, UT, WY |

6 | 51 | 25 |

| Pacific | AK, CA, HI, OR, WA |

11 | 172 | 48.5 |

| Total | 99 | 1404 |

Figure 3.

Relationship Between Number of Otolaryngology Residency Positions and Percentage of Participants Staying in Region

Table 3 displays the geographic distribution of each participant, whether they stayed in their home region or not, while Table 4 displays the percentage of study participants from each medical school region that matched in a different region for residency. With the exception of New England, the percentage of subjects staying in the same region is higher than those relocating to any other specific region. The general trend demonstrated in Table 4 is that a higher percentage of residents originate from an adjacent geographic region.

Table 3.

Regional Distribution of All Participants

| Program Region | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical School Region |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1 | 19% | 26% | 5% | 11% | 9% | 0% | 7% | 2% | 21% |

| 2 | 9% | 44% | 14% | 9% | 8% | 2% | 3% | 1% | 9% |

| 3 | 1% | 10% | 46% | 11% | 11% | 6% | 5% | 2% | 8% |

| 4 | 2% | 10% | 17% | 39% | 9% | 4% | 5% | 5% | 9% |

| 5 | 4% | 17% | 10% | 6% | 35% | 7% | 7% | 4% | 9% |

| 6 | 2% | 11% | 6% | 3% | 21% | 27% | 15% | 9% | 6% |

| 7 | 2% | 7% | 6% | 6% | 15% | 9% | 44% | 6% | 5% |

| 8 | 0% | 6% | 6% | 16% | 6% | 3% | 22% | 25% | 16% |

| 9 | 9% | 9% | 16% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 2% | 2% | 48% |

Key

1 – New England

2 – Mid-Atlantic

3 – East North Central

4 – West North Central

5 – South Atlantic

6 – East South Central

7 – West South Central

8 – Mountain

9 – Pacific

Table 4.

Regional Distributions of Relocating Study Participants

| Program Region | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical School Region |

1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 1 | X | 33% | 7% | 13% | 11% | 0% | 9% | 2% | 26% |

| 2 | 16% | X | 24% | 17% | 14% | 4% | 6% | 2% | 17% |

| 3 | 2% | 19% | X | 20% | 20% | 11% | 9% | 5% | 15% |

| 4 | 3% | 17% | 28% | X | 15% | 6% | 8% | 8% | 15% |

| 5 | 6% | 27% | 15% | 10% | X | 11% | 11% | 7% | 14% |

| 6 | 2% | 15% | 8% | 4% | 29% | X | 21% | 13% | 8% |

| 7 | 4% | 12% | 11% | 10% | 27% | 16% | X | 11% | 8% |

| 8 | 0% | 8% | 8% | 21% | 8% | 4% | 29% | X | 21% |

| 9 | 18% | 18% | 32% | 8% | 8% | 8% | 4% | 4% | X |

Key

1 – New England

2 – Mid-Atlantic

3 – East North Central

4 – West North Central

5 – South Atlantic

6 – East South Central

7 – West South Central

8 – Mountain

9 – Pacific

Discussion

Our data indicate that the majority of otolaryngology applicants relocate for residency training. Evaluation of the entire study population revealed that only 40% of subjects stayed within their geographic region for training, with even lower percentages staying in the same state or metropolitan area. When comparing medical school and residency geographic distribution of all subjects by region (Table 3), it is true that the largest percentage of subjects remained in the same region for residency (with the exception of New England), but the percentages of subjects who stayed are all below 50%. The rate of retention was also low among subjects that had remained in the same area for college and medical school. Though some may view this subgroup of participants as more rooted in their current location and therefore less willing to move away for residency, our data show that less than 45% of these participants stayed in their region and less than 30% remained in the same state or metropolitan area.

Gender and couples match status does not influence whether applicants stay in their geographic region for residency. Subjects with USMLE step 1 scores above 240 were more likely to leave their geographic region for residency. While we can hypothesize that applicants with higher scores may wish to relocate to attend a more prestigious program outside their geographic area, it is impossible to know the true intentions of applicants with a more competitive score.

Some regional differences were noted in the likelihood of a subject staying in the same geographic region for residency, with retention rates ranging from 19.3 to 48.5%. The authors hypothesize that regions with fewer residency positions have lower retention rates because applicants more frequently travel outside of their region for residency interviews. Conversely, applicants from regions with more residency positions have higher retention rates, potentially due to less frequent travel outside of a geographic region for interviews. These data could also point to an applicant’s preference to stay within their region for residency training, as applicants with more choices in their geographic region opt to choose those programs closer to their medical school. The authors also question whether favoritism from certain states or cities also plays a part in the observed trend.

An implied assumption of this study is that the geography of the applicant’s undergraduate or medical school represents his or her “home” geography. This is not necessarily true, as many applicants choose to attend college or medical school away from their hometown. We attempted to rectify this problem by evaluating birth city and permanent address for each subject, but discovered that these measures also fell short because birth city is not necessarily equivalent to hometown and permanent address was usually in the same location as the medical school. This can be considered a limitation of the study, since the inability to identify a subject’s true home geography makes biases toward geographic location harder to predict.

Another limitation of this study is number of applicants enrolled (n=1107) represents 79% of total otolaryngology residency applicants from 2009-2013. While it is possible that the 21% of applicants not included in this study have different matching statistics from our study population, this is less likely due to the subject pool comprising a large percentage of total applicants. There are no published data about the entire otolaryngology applicant pool, which makes it difficult to verify whether any selection bias is present.

A third limitation of this study is that the data analysis was performed based on where subjects matched without evaluating their rank list. Without rank list information we cannot say whether subjects wanted to stay within their region or relocate for residency training. Although the data indicate that the majority of subjects do match in a different geographic area from their medical school, these data do not specify if an applicant is matching at the top or the bottom of their rank list. Further studies analyzing the successful rank list position at which an applicant matches could help clarify this study by comparing the matching patterns of applicants matching at the top of their list compared to those matching at the bottom.

There are many reasons why an applicant matches outside of their home geography, which makes it difficult to make concrete conclusions about this data. We cannot control for factors such as rank position of the applicant on the programs’ rank lists; variable number of programs in each region; and number of applications per applicant and the geographical distribution of these applications. Despite these limitations the authors believe this study provides insights into the geographic retention rates of applicants that can aid residency programs in deciding which applicants to invite to interview.

Conclusion

Within this studied applicant pool, the majority of subjects matched outside of the geographic region of their medical school. Although studies indicate that geographic location is an important consideration for applicants, the many variables that contribute to where an applicant matches makes it difficult to predict matching trends based on geography alone. The data did demonstrate that subjects often match away from their “home” geography, and we believe that this is an important consideration for programs during interview season. The true intentions of applicants are difficult to predict, and do not follow trends based on gender, couples match status, or USMLE step 1 scores. Based on our data, the authors recommend against using geography as a key factor when inviting applicants to interview.

Acknowledgments

None

Source of Financial Support or Funding: Supported by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 TR001082. Contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Footnotes

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

All authors report no financial disclosures.

Presented at Triological Society Combined Sections Meeting, January 22-24, 2015, Coronado Island, California, USA

References

- 1.Parker AM, Petroze RT, Schirmer BD, Calland JF. Surgical Residency Market Research—What are Applicants Looking For? Jour Surg Education. 2013;70(2):232–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Crace PP, Nounou J, Engel AM, Welling RE. Attracting Medical Students to Surgical Residency Programs. The American Surgeon. 2006;72:485–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharp S, Puscas L, Schwab B, Lee WT. Comparison of applicant criteria and program expectations for choosing residency programs in the otolaryngology match. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(2):174–9. doi: 10.1177/0194599810391722. doi:10.1177/0194599810391722. Epub 2011 Jan 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nuthalapaty FS, Jackson JR, Owen J. The Influence of Quality-of-Life, Academic, and Workplace Factors on Residency Program Selection. Academic Medicine. 2004;79(5):417–25. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSantis M, Marco CA. Emergency Medicine Residency Selection: Factors Influencing Candidate Decisions. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(6):559–61. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aagaard EM, Julian K, Dedier J, Soloman I, Tillisch J, Pérez-Stable EJ. Factors Affecting Medical Students’ Selection of an Internal Medicine Residency Program. Jour of the National Medical Association. 2005;97(9):1264–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yousuf SJ, Kwagyan J, Jones LS. Applicants’ Choice of an Ophthalmology Residency Program. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(2):423–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.07.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falcone JL. Home-Field Advantage: The Role of Selection Bias in the General Surgery National Residency Matching Program. Jour Surg Education. 2013;70(4):461–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Resident Matching Program [Last accessed February 1, 2015];Results and Data: Main Residency Match. http://www.nrmp.org/match-data/nrmp-historical-reports/