Abstract

Background:

Vaginal delivery is one of the challenging issues in medical ethics. It is important to use an appropriate instrument to assess medical ethics attitudes in normal delivery, but the lack of tool for this purpose is clear.

Objectives:

The aim of this study was to develop and validate a questionnaire for the assessment of women’s attitude on medical ethics application in normal vaginal delivery.

Patients and Methods:

This methodological study was carried out in Iran in 2013 - 2014. Medical ethics attitude in vaginal delivery questionnaire (MEAVDQ) was developed using the findings of a qualitative data obtained from a grounded theory research conducted on 20 women who had vaginal childbirth, in the first phase. Then, the validation criteria of this tool were tested by content and face validity in the second phase. Exploratory factor analysis was used for construct validity and reliability was also tested by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient in the third phase of this study. SPSS version 13 was used in this study. The sample size for construct validity was 250 females who had normal vaginal childbirth.

Results:

In the first phase of this study (tool development), by the use of four obtained categories and nine subcategories from grounded theory and literature review, three parts (98-items) of this tool were obtained (A, B and J). Part A explained the first principle of medical ethics, part B pointed to the second and third principles of medical ethics, and part J explained the fourth principle of medical ethics. After evaluating and confirming its face and content validity, 75 items remained in the questionnaire. In construct validity, by the employment of exploratory factor analysis, in parts A, B and J, 3, 7 and 3 factors were formed, respectively; and 62.8%, 64% and 51% of the total variances were explained by the obtained factors in parts A, B and J, respectively. The names of these factors in the three parts were achieved by consideration of the loading factor and medical ethics principles. The subscales of MEAVDQ showed significant reliability. In parts A, B and J, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were 0.76, 0.72 and 0.68, respectively and for the total questionnaire, it was 0.72. The results of the test–retest were satisfactory for all the items (ICC = 0.60 - 0.95).

Conclusions:

The present study showed that the 59-item MEAVDQ was a valid and reliable questionnaire for the assessment of women’s attitudes toward medical ethics application in vaginal childbirth. This tool might assist specialists in making a judgment and plan appropriate for women in vaginal delivery management.

Keywords: Medical Ethics; Natural Childbirth; Validation Studies, Attitude; Women

1. Background

Childbirth is a unique experience for a mother with a longstanding effect on her dignity (1). The conducts of caring team and observing medical ethics during vaginal delivery can significantly affect this emotional experience. Medical ethics principally include moral commitment, respect for autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (2, 3). To attain these ethical goals, healthcare providers are devoted to an extensive variety of commitments (4).

Studies have shown that most physicians do not have a correct understanding of patients’ preferences; therefore, they cannot appropriately apply medical ethics to medical care. This issue is especially true in the case of delivery. For instance, it is reported usually that women do not receive sufficient information about the interventions in labor (4, 5).

Woman’s physical and emotional responses to delivery are affected by different factors such as cultural context, personal characteristics and traits and religious beliefs. The obstetrician and midwives should specially be aware of the impact of these factors on delivery (6).

Though observing medical ethics and understanding mothers’ prefernces and attitudes are important during labor, no suitable questionnaire is available for assessing this multidimensional construct (7).

Patient attitude is not only an important indicator for assessing the health care quality (8), but also would affect the healthcare professionals’ behaviors (9). Although a huge literature is available on the dimensions of medical ethics (10, 11), little attention has been paid to the development of appropriate instruments for assessing this important dimension of medical and healthcare ethics (12, 13). Some existing instruments are also incomplete and assess only one or few dimensions of the issue. For instance, Kroemeke developed an instrument for assessing perceived autonomy in old age (14). As ethical issues are affected by socio-cultural contexts, it is important that this issue be investigated through appropriate instruments with special attention to peoples’ native cultures and values. Iran has an Islamic culture and people expect to receive high quality services; they are culturally sensitive. Then, an indigenous instrument should be developed for assessing Iranian women’s attitudes on the application of medical ethics in labor.

2. Objectives

This study aimed a) to develop a questionnaire for assessing women’s attitude on medical ethics application in labor and delivery; and b) to assess the validity and reliability of the instrument.

3. Patients and Methods

This was a methodological study conducted through a mixed-methods design. The study consisted of two main qualitative and quantitative phases, respectively. The study was carried out in Iran during 2013 - 2014.

3.1. Selection of Subjects

The study population consisted of females who recently had childbirth in Mashhad and Kerman cities, Iran. The inclusion criteria were low-risk pregnancy and childbirth, giving birth at a governmental or private hospital, and experiencing a vaginal delivery. A decision to withdraw was selected as exclusion criteria.

In the qualitative phase of the study, the participants were selected via purposive sampling. Among the 23 women who were invited in this phase, three were excluded because of reluctance to continue their participation. In the quantitative phase, a convenient sampling method was employed and 250 women with the inclusion criteria were recruited for instrument validation. It is recommended to have 150 - 300 subjects for factor analysis (15).

3.2. Instrument Development

The items of the instrument were developed through a qualitative study using a grounded theory methodology. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with 20 women who had vaginal delivery in private hospitals affiliated with Mashhad and Kerman Universities of Medical Sciences. Each interview lasted for 45 - 60 minutes. Detailed characteristics of the 20 participants are presented in Table 1. All the women were interviewed by one interviewer. At first, women were asked about their opinion about childbirth, and then the initial question from each mother was “can you explain your experience on ethics application during labor and delivery?” The participants were patronized to explain all their experiences by probing questions. Sampling was continued until data saturation occurred. All the interviews were transcribed verbatim; then, the text of each interview was read and evaluated for several times to obtain an overall sense of the content. Meaning units, i.e. the main statement in the text, were recognized, condensated and coded. Then, categories and subcategories were formed through constant comparison method. Finally, 98 conceptual codes (representing 98-items) were emerged and put in four main categories (each with 2 - 3 subcategories; totally nine subcategories). The 98 conceptual codes constituted the first draft of the questionnaire.

Table 1. Detailed Demographics of Participants in Qualitative Study.

| Variables | Valuesa |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| < 18 | 2 (10) |

| ≥ 18 | 18 (90) |

| Parity | |

| Primiparous | 12 (60) |

| Multiparous | 8 (40) |

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 2 (10) |

| Elementary school | 5 (25) |

| Secondary school | 3 (15) |

| High school | 5 (25) |

| Post-graduate | |

| Hospital of childbirth | 5 (25) |

| Public | 12 (60) |

| Private | 8 (40) |

aValues are presented as frequency (percent).

3.3. Tool Validation

3.3.1. Face and Content Validity

The 98 conceptual codes extracted in the qualitative phase of the study constituted the first draft of the questionnaire. Content validity and face validity of the 98-items questionnaire was evaluated in a panel of experts.

3.3.1.1. Face Validity

Both qualitative and quantitative methods were applied in face validity. Qualitative face validity was evaluated by asking the opinion of experts including a sample of the target group and 10 faculty members, among which, six were experts in the areas of instrument development and reproductive health and four in medical ethics.

The expert panel assessed the questionnaire for reasonableness, appropriateness, attractiveness, and logical sequence of items. In addition, 12 women were randomly selected from the target group. The women were requested to read each item loudly and illustrate their understanding of it. In addition, they were asked to comment on the complexity, relevance, and ambiguity of the items. The items were edited and reworded based on their statements.

In quantitative face validity, impact score method was used to recognize the importance of each item. An impact score of 1.5 or higher showed that the intended item was appropriate (16, 17). The revised questionnaire was then given to 12 women and then the score of each question was assessed separately. The five-point Likert scale answers consisted of: very important (score 5), important (score 4), averagely important (score 3), slightly important (score 2), and not important (score 1). The questions that received a score more than 1.5 were retained for subsequent analyses. Finally, the face validity of the revised questionnaire was evaluated again by three women.

3.3.1.2. Content Validity

Content validity was also evaluated by qualitative and quantitative methods. In the qualitative phase, we invited an expert panel to evaluate and discuss the essentiality of the questionnaire items, its wording and scaling, and its relevance. In quantitative method, content validity ratio (CVR) and content validity index (CVI) were tested for each item. If CVR was greater than the criterion of the Lawshe’s table (18) for each item, the item was weighed as essential; if not, it was omitted. According to the Lawshe table (18), an acceptable CVR value for 10 experts is 0.62.

The CVI for each item scale was the proportion of experts who rated an item as 3 or 4 on a 4-point scale (19, 20). Clarity, simplicity, and relevancy of each item were scored in a four-point Likert scale (from 1: not relevant, not simple, and not clear to 4: very relevant, very simple, and very clear). Items with scores less than 0.7 were omitted. We also calculated CVR and CVI for the total scale before and after of deleting the items. At this stage, 75 items remained in the instrument and it was named as medical ethics attitude in vaginal delivery questionnaire (MEAVDQ).

3.3.2. Construct Validity

The level to which an instrument evaluates the concerned construct is called construct validity (18). The construct validity was determined through exploratory factor analysis (EFA). EFA was conducted using principal component analysis with varimax rotation. EFA was conducted on the 75-item version of the MEAVDQ. Items with a loading factor exceeding 0.4 were considered to belong to a subscale. If an item was loaded on more than one factor, we would decide on its loading factor. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity and the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test were used to respectively determine the appropriateness of the factor analysis model and the sampling adequacy.

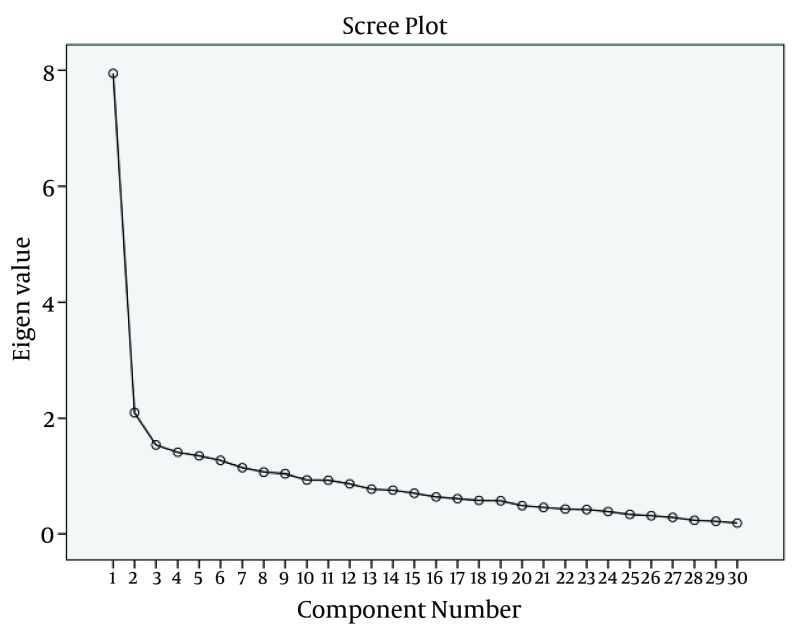

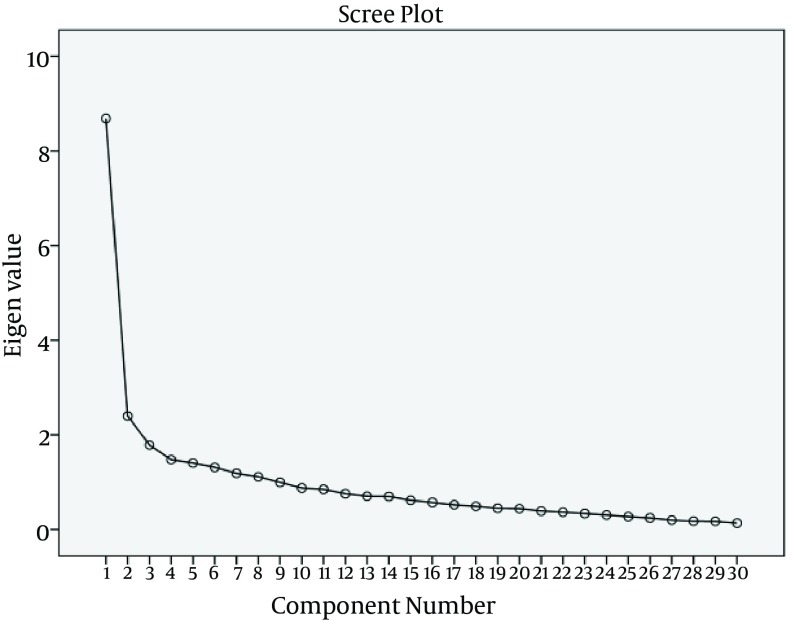

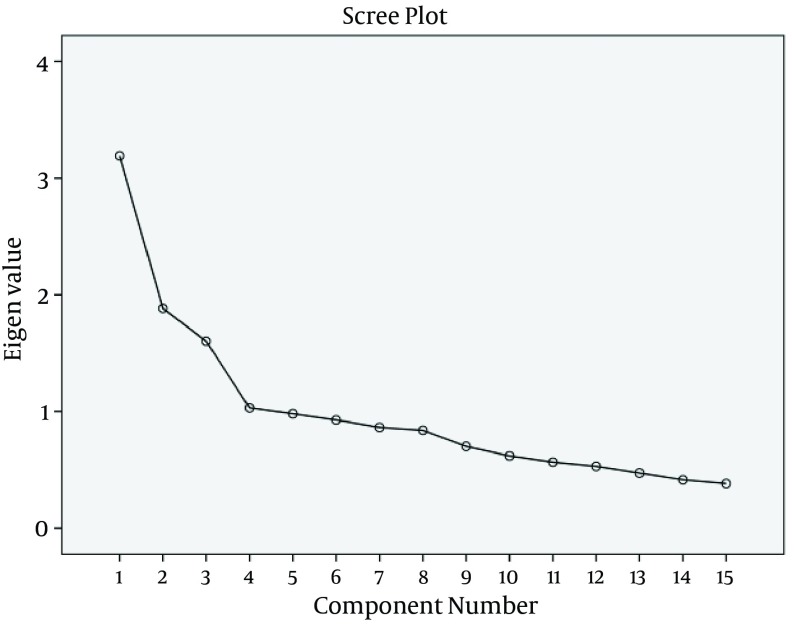

The suitable number of factors for the parts of questionnaire was determined by Eigen value criterion (Eigen value > 1) and Scree plot. For the assessment of inter-item correlation, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was calculated as well as the Pearson’s correlations between subscales; for validity of the subscales, the total score was calculated.

3.3.3. Reliability Assessment

Reliability was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha coefficient (21). Test-retest over a course of two weeks for 30 women was performed by inter-class correlation coefficient (ICC).

3.4. Ethical Considerations

Permission was granted by the Ethics Committee of Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran (project code: 920487). All the participants were aware of the aim of the study, the confidentiality of their interviews and their right to withdraw at any time. All the participants signed a written informed consent before participation.

3.5. Statistical Analysis

All the analyses were performed using SPSS version 13. Percent was used for data description; central and dispersion parameters (mean and standard deviation) were also used. All the statistical tests were also two-sided and P ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

4. Results

4.1. Tool Development

The first draft of the 98-items instrument was formed through a grounded theory study and extensive literature review. This instrument was divided into three parts of A, B and J. Part A investigated women’s attitude toward respect to autonomy in vaginal delivery (the first principle of medical ethics). This part consisted of 36 items. Part B investigated women’s attitudes toward beneficence and non-maleficence in vaginal delivery (the second and third principles of medical ethics). This part had 42-items. Part J investigated women’s attitudes toward justice in vaginal delivery (the fourth principle of medical ethics). This subscale had 20 items.

4.2. Tool Validation

4.2.1. Face and Content Validity

4.2.1.1. Face Validity

In qualitative face validity, by consideration of the expert panel, two items were deleted due to lack of harmony between the items and their equivalent category and content overlap. One item was also omitted due to the opposition of participants. One item had an impact score less than 1.5 and thus was omitted in the quantitative stage.

4.2.1.2. Content Validity

In qualitative content validity, we changed two items according to the experts’ recommendations. In the quantitative stage, CVR of all the items was between 0.63-1, except for 12-items that had a CVR < 0.62 and therefore were deleted. Seven items were also deleted as they had a CVI less than 0.7. CVI of other items were between 0.8-1. CVI of clarity, simplicity and relevance were 0.89, 0.90 and 0.88, respectively, and SCVI/Ave was 0.89. With deleted items in CVR and CVI, the mean CVR and CVI for the total scale were improved (Table 2).

Table 2. Mean Content Validity Ratio and Content Validity Index Before and After Omitting the Items.

| Content Validity | Before | After |

|---|---|---|

| CVR | 0.73 | 0.78 |

| CVI | 0.82 | 0.89 |

Abbreviations: CVI, content validity index; CVR, content validity ratio.

4.2.2. Construct Validity and Reliability Assessment

4.2.2.1. Construct Validity

Construct validity of this instrument was evaluated by 250 women with mean age of 26.7 ± 5.60 years. Detailed demographic data of these women are presented in Table 3.

Table 3. Detailed Demographic Data of Participants in Quantitative Study.

| Variables | Valuesa |

|---|---|

| Education | |

| Illiterate | 34 (13.6) |

| Elementary school | 37 (14.8) |

| Secondary school | 56 (22.4) |

| High school | 93 (37.2) |

| Post-graduate | 30 (12) |

| Number of spontaneous child births | |

| 1 | 97 (38.8) |

| 2 | 98 (39.2) |

| 3 | 40 (16) |

| ≥ 4 | 15 (6) |

aValues are presented as frequency (percent).

At first, primary analysis was directed for normality and linearity of the items. The names of these categories in three parts were achieved by considering the loading factor of categories and obtained content from medical ethics principles.

In part A, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) index (0.82) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with X2 of 268.12 (df = 435), in part B, KMO index (0.82) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with chi square of 3399.1 (df = 435), and in part J, KMO index (0.71) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity with X2 of 670.6 (df = 105), were applied for evaluation of the adequacy of samples for factor analysis (P < 0.0001).

Part A consisted of 30 items which were divided into three categories by considering EFA and scree plot (Figure 1) for construct validity. The first category consisted of providing necessary information and it had eight items. The second category was mother’s privacy, consisting of six items. The third category consisted of interaction with mother, with five items. Other categories in this part consisted of 1 - 2 items, which did not seem to be suitable for categorization; therefore, they were eliminated. One item in this part had a loading factor of < 0.4; therefore, it was eliminated. Part B had 30 items; by considering EFA and scree plot (Figure 2) for construct validity, they were divided into seven categories. The first category was the importance of the role of midwife and consisted of five items. The second category was related to securing and ensuring the health of the fetus and consisted of five items. The third category was related to mother’s pain, with four items. The fourth category dealt with mother’s stress, with three items. The fifth category dealt with mother’s health, consisting of three items. The sixth category assessed the mother’s need for pain reductions, with four items. The last category of this part was on mother’s relaxation and consisted of three items. Other categories in this part consisted of 1 - 2 items, which were eliminated because they were not suitable for categorization. One item in this part had a loading factor of < 0.4 and was eliminated. Part J had 15 items, and by considering EFA and scree plot (Figure 3) for construct validity, they were divided into three categories. The first category was concerned trust in midwife, with six items. The second category dealt with the necessity to meet the mother’s requests, consisting of three items. The third category was related to the application of equal opportunities for every mother and consisted of four items. Two categories in this part consisted of one item and were not suitable as a category; therefore, they were eliminated. One item in this part had a loading factor of < 0.4 and was eliminated.

Figure 1. The Scree Plot of Part A. The curve reaches a fairly stable plateau after three factors.

Figure 2. The Scree Plot of Part B. The curve reaches a fairly stable plateau after seven factors.

Figure 3. The Scree Plot of Part J. The curve reaches a fairly stable plateau after three factors.

Three categories of part A explained a total of 62.8% of variance in this part; seven categories of part B explained a total of 64% of variance in this part, and three categories of part J explained a total of 51% of variance in this part (Table 4).

Table 4. Central and Dispersion Parameters in Parts of Medical Ethics Attitude in Vaginal Delivery Questionnaire.

| Parts | Valuesa | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | |||

| Providing the necessary information | 36.6 ± 3.9 | 21 | 40 |

| Mother’s privacy | 25.7 ± 4.5 | 12 | 30 |

| Interaction with mother | 23.4 ± 2.2 | 13 | 25 |

| B | |||

| The importance of the role of midwife | 23.4 ± 2.8 | 9 | 25 |

| Ensuring the health of the fetus | 23.7 ± 2.1 | 11 | 25 |

| Mother’s pain | 16.8 ± 3.5 | 7 | 20 |

| Mother’s stress | 14.7 ± 1.3 | 7 | 15 |

| Mother’s health | 13.5 ± 1.8 | 6 | 15 |

| Mother’s need for pain reductions | 17.9 ± 2.6 | 8 | 20 |

| Mother’s relaxation | 14.1 ± 1.5 | 8 | 15 |

| J | |||

| Trust in the midwife | 28.1 ± 2.8 | 11 | 30 |

| The necessity to meet the mother’s requests | 13.8 ± 1.6 | 3 | 15 |

| The application of equal opportunities for every mother | 16.7 ± 2.8 | 7 | 20 |

aValues are presented as mean ± SD.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients between the MEAVDQ subscales were calculated as an internal criterion for the validity of subscales. The results indicated a correlation among items and the total score of that dimension (Table 5).

Table 5. Inter-Correlation Coefficient of the Medical Ethics Attitude in Vaginal Delivery Questionnaire Categories With Total Score and Reliability Coefficient for Each Category.

| Parts | Pearson’s Correlation | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|---|---|

| A | ||

| Providing the necessary information | 0.83 | 0.77 |

| Mother’s privacy | 0.85 | 0.79 |

| Interaction with mother | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| B | ||

| The importance of the role of midwife | 0.74 | 0.80 |

| Ensuring the health of the fetus | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| Mother’s pain | 0.73 | 0.69 |

| Mother’s stress | 0.71 | 0.78 |

| Mother’s health | 0.67 | 0.60 |

| Mother’s need for pain reductions | 0.73 | 0.65 |

| Mother’s relaxation | 0.68 | 0.68 |

| J | ||

| Trust in the midwife | 0.73 | 0.71 |

| The necessity to meet the mother’s requests | 0.53 | 0.67 |

| The application of equal opportunities for every mother | 0.63 | 0.60 |

The final 59-item version of the MEAVDQ was presented as a self-reporting questionnaire which consisted of 19 items for part A (the first principle of medical ethics), 27 items for part B (the second and third principles of medical ethics), and 13 items for part J (the fourth principle of medical ethics). All the questions were scored based on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = I do not agree, 2 = I agree a little, 3 = I agree to some extent, 4 = I agree to a great degree, 5 = I agree completely). MEAVDQ is available upon request from the first author.

4.2.2.2. Reliability Assessment

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for parts A, B and J of the questionnaire as a whole were 0.76, ranging from 0.71 to 0.79; 0.72, ranging from 0.60 to 0.8; and 0.67, ranging from 0.60 to 0.71, respectively (Table 5).

The test–retest correlates also showed that the MEAVDQ subscales had suitable degrees of constancy (ICC = 0.60-0.95).

5. Discussion

This paper reported the development and validation of the MEAVDQ to assess women’s attitudes toward the application of medical ethics in vaginal childbirth. The key foundation for generating the items of this instrument was a grounded theory research. As verified by factor loading, the instrument assessed women’s attitudes about the application of medical ethics in normal vaginal childbirth. This instrument was divided into three parts: A, B and J.

Part A of this instrument evaluated the respect toward women’s autonomy in childbirth. This part pointed to the first principle of medical ethics. Giving information to woman about childbirth by a midwife enhances woman’s self-confidence and this self-esteem improves sharing of the decision-making process between the mother and the midwife or the obstetrician. Providing necessary information for women during labor was one of the categories in part A of our instrument.

Part B of the instrument assessed the application of beneficence and non-maleficence in vaginal childbirth. This section noted the second and third principles of medical ethics.

Part J of our tool considered the application of justice in vaginal childbirth. This section investigated the fourth principle of medical ethics.

Our results in part A are in agreement with the study of Vlug et al. (12) who designed a questionnaire and tested its validity and reliability for the assessment of factors influencing self-perceived dignity. Four domains were in this study: evaluation of self in relation to others, functional status, mental state, and situational aspects of caring (12). Two domains of evaluation of self in relation to others and situational aspects of caring in Vlug et al. (12) instrument are in line with part A in our study.

Asemani et al. developed and validated a questionnaire to evaluate medical students and residents’ responsibilities in clinical settings (22). In this study, the alpha coefficient is similar to alpha coefficient in part B of our instrument. The results of this study were also in line with those of part B of our instrument.

The results of content and face validity in the present study showed that the items of the instrument were comprehensible and related to the Iranian culture. Content validity was assessed by a team of expert specialists in qualitative and quantitative methods. In general, the assessment of reliability and validity showed that the whole questionnaire had acceptable validity and reliability levels. We assessed construct validity using EFA. EFA could successfully identify the factors in three parts.

The MEAVDQ had a high Cronbach’s alpha which confirmed the great internal consistency and suitable reliability of the tool and its three parts. The test-retest method was also used to evaluate the stability of the scale. The results of this method also showed a high ICC between the scores of the test and the retest measurements, confirming the stability and reliability of the MEAVDQ.

The main strength of this study was the development of a context-bound scale to assess Iranian women’s attitudes about the application of medical ethics in natural childbirth. The MEAVDQ is a simple, valid, reliable, and context-based scale.

We developed and validated the MEAVDQ base on Iranian socio-cultural context. However, its validity for using in other cultures was not assessed. Therefore, further studies are suggested to confirm its validity and applicability in different cities. Moreover, assessment of validity and applicability of the MEAVDQ for using in other eastern and Islamic countries can be recommended.

We hope that MEAVDQ can assess women’s attitudes toward medical ethics in natural childbirth. The findings of this study may also assist healthcare providers in understanding women’s preferences and needs.

Acknowledgments

The researchers appreciate all the women and midwives who participated in this study. The authors are grateful for the financial support provided by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contribution:Firoozeh Mirzaee Rabor developed the study concept and design and the acquisition of data, interpretations of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Khadigeh Mirzaii Najmabadi, Moghaddameh Mirzaee, Ali Taghipour, Seyed Hosein Fattahi Masoum and Masoud Fazilat Pour developed the protocol, analysis of data and drafting of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure:This project was a part of fulfillment for a Ph.D. degree in reproductive health and was supported by Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran [code: 920487].

Funding/Support:None declared.

References

- 1.Wiegers TA. The quality of maternity care services as experienced by women in the Netherlands. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2009;9:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-9-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meslin EM, Schwartz PH. How bioethics principles can aid design of electronic health records to accommodate patient granular control. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30 Suppl 1:S3–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3062-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nguah SB. Ethical aspects of arranging local medical collaboration and care. J Clin Ethics. 2014;25(4):314–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holt GR. Ethical conduct of humanitarian medical missions: I. Informed Consent. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2012;14(3):215–7. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2011.1643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lundgren I, Dahlberg K. Midwives' experience of the encounter with women and their pain during childbirth. Midwifery. 2002;18(2):155–64. doi: 10.1054/midw.2002.0302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hansen SE. [A reading of Foucault's "The Birth of the Clinic"]. Dan Medicinhist Arbog. 2014;42:121–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Magee H, Parsons S, Askham J. Measuring dignity in care for older people. 2008. Available from: http://www.ageuk.org.uk/documents/ en-gb/for-professionals/research/measuring%20dignity%20inAvailable from: %20care%20(2008) http://www.ageuk.org.uk/documents.

- 8.Henoch I, Browall M, Melin-Johansson C, Danielson E, Udo C, Johansson Sundler A, et al. The Swedish version of the Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of the Dying scale: aspects of validity and factors influencing nurses' and nursing students' attitudes. Cancer Nurs. 2014;37(1):E1–11. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e318279106b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azeem E, Gillani SW, Siddiqui A, Shammary HAA, Poh V, Syed Sulaiman SA, et al. Knowledge, Attitude and Behavior of Healthcare Providers towards Breast Cancer in Malaysia: a Systematic Review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16(13):5233–5. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.13.5233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moutel G. [The wishes and autonomy of the patient faced with a care decision]. Soins. 2015;(796):43–5. doi: 10.1016/j.soin.2015.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Irmak N. Professional ethics in extreme circumstances: responsibilities of attending physicians and healthcare providers in hunger strikes. Theor Med Bioeth. 2015;36(4):249–63. doi: 10.1007/s11017-015-9333-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vlug MG, de Vet HC, Pasman HR, Rurup ML, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD. The development of an instrument to measure factors that influence self-perceived dignity. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(5):578–86. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chochinov HM, Hassard T, McClement S, Hack T, Kristjanson LJ, Harlos M, et al. The patient dignity inventory: a novel way of measuring dignity-related distress in palliative care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;36(6):559–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroemeke A. [Perceived Autonomy in Old Age scale: Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Polish adaptation]. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49(1):107–17. doi: 10.12740/PP/22616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hogarty KY, Hines CV, Kromrey JD, Ferron JM, Mumford KR. The quality of factor solutions in exploratory factor analysis: The influence of sample size, communality, and overdetermination. Educ Psychol Measurement. 2005;65(2):202–26. doi: 10.1177/0013164404267287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lacasse Y, Godbout C, Series F. Health-related quality of life in obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(3):499–503. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00216902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juniper EF, Guyatt GH, Streiner DL, King DR. Clinical impact versus factor analysis for quality of life questionnaire construction. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(3):233–8. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(96)00377-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lawshe CH. A quantitative approach to content validity. Pers Psychol. 1975;28:563–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6570.1975.tb01393.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Creswell WJ, Plano LV. Designing and conducting mixed method research. Canada: Sage Publication; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.DeVon HA, Block ME, Moyle-Wright P, Ernst DM, Hayden SJ, Lazzara DJ, et al. A psychometric toolbox for testing validity and reliability. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(2):155–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2007.00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cronbach LJ, Meehl PE. Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychol Bull. 1955;52(4):281–302. doi: 10.1037/h0040957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Asemani O, Iman MT, Khayyer M, Tabei SZ, Sharif F, Moattari M. Development and validation of a questionnaire to evaluate medical students' and residents' responsibility in clinical settings. J Med Ethics Hist Med. 2014;7:17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]