Abstract

Deciphering many roles played by inositol lipids in signal transduction and membrane function demands experimental approaches that can detect their dynamic accumulation with subcellular accuracy and exquisite sensitivity. The former criterion is met by imaging of fluorescence biosensors in living cells, whereas the latter is facilitated by biochemical measurements from populations. Here, we introduce BRET-based biosensors able to detect rapid changes in inositol lipids in cell populations with both high sensitivity and subcellular resolution in a single, convenient assay. We demonstrate robust and sensitive measurements of PtdIns4P, PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 dynamics, as well as changes in cytoplasmic Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels. Measurements were made during either experimental activation of lipid degradation, or PI 3-kinase and phospholipase C mediated signal transduction. Our results reveal a previously unappreciated synthesis of PtdIns4P that accompanies moderate activation of phospholipase C signaling downstream of both EGF and muscarinic M3 receptor activation. This signaling-induced PtdIns4P synthesis relies on protein kinase C, and implicates a feedback mechanism in the control of inositol lipid metabolism during signal transduction.

Keywords: Phosphoinositides, PI4-kinase, BRET, EGF receptor, GPCR, PKC The total number of words in abstract is 168

INTRODUCTION

Inositol lipids are a uniquely important class of phospholipids built from a diacylglycerol (DAG) backbone linked to an inositol ring via a phosphodiester linkage. Reversible phosphorylation of the inositol ring at positions 3, 4 and 5 by a plethora of lipid kinases and phosphatases results in the dynamic formation of seven different phosphoinositides (PPIn) [1, 2]. In addition, activation of receptor tyrosine kinases (RTK) or G-protein coupled receptors (GPCR) can acutely regulate PPIn levels in response to a variety of external signals. These lipids were first recognized as precursors of the second messengers inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate [Ins(1,4,5)P3] and DAG [3], but in recent years it has become clear that PPIns also have important roles in several cellular functions ranging from the control of ion channels to vesicular trafficking and cell motility [4]. Because of their rapid dynamics and general importance, measuring the changes in the level of these lipids in living cells is paramount to understanding their distinct localizations and functions.

In the past three decades, several techniques were used to determine PPIn levels. One of the first methods was the metabolic labeling of the cells with myo-[3H]inositol or 32P-phosphate followed by lipid extraction and separation by thin-layer chromatography [5]. These studies were the first steps of the inositol lipid research field but they required millions of cells and they could not give any information about the subcellular localizations of the PPIns. Measurements of the total lipid mass by mass spectrometry have been achieved with great sensitivity, however it still suffered from the lack of spatial resolution and it could not allow resolution of different regio-isomers [6]. Other groups used fluorescently labeled lipids, which had the advantage of following spatial and compartmentalized changes in living cells [7], but their major limitation was that the probes did not have the same hydrophobic character and greatly altered the distribution of endogenous lipids inside the cell. Another approach can be the application of antibodies raised against specific isomers of inositol lipids [8] however it needed fixed cells, thus following the dynamic changes of the PIs was impracticable. With the introduction of GFP-fused protein domains that recognize PPIns in living single cells, our ability to follow localized changes has been significantly improved and a plethora of knowledge has accumulated regarding the spatial distribution and dynamics of PPIns [9].

Although these methods are not without limitations [10], they are still enormously useful in exploring the PPIn landscape. One difficulty that is increasingly obvious with these methods is the quantification of the changes and the generation of data from a significant number of cells. A good example of fine-tuning these methods was recently published when demonstrating orthogonal lipid sensors, capable of in situ quantification of lipid pools in live single cells [11, 12]. As an other approach, to overcome the difficulties of quantification we developed a new molecular tool-set to monitor various inositol lipid species in the plasma membrane (PM) of stimulated living cells. Here we show that balanced expression of luciferase-fused PPIn-recognizing protein domains and a Venus protein targeted to the PM, allowed us to perform bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) measurements reflecting PPIn changes in populations of transiently transfected HEK 293T cells.

As PPIns level can quickly change upon hormonal stimulation and this can alter several cellular mechanisms, it is very important for the cells to be able to quickly replace the PPIns and thus to regain their responsiveness to external stimuli. There are several papers, which confirm experimentally and mathematically that following phospholipase C (PLC) activation the resulting Ins(1,4,5)P3 kinetics are more rapid compared with the decrease and subsequent recovery in PM phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PtdIns(4,5)P2] [13–15]. Therefore, in parallel to degradative phospholipase C, PPIn resynthetic pathways have to be activated upon strong hormonal stimulation. It was also demonstrated that the resynthesis of PM phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate (PtdIns4P) and PtdIns(4,5)P2 requires a wortmannin-sensitive phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase (PI4K) enzyme [16], now identified as PI4KA [17]. Activation of PI4KA is indispensable in the quick resynthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 because phosphatidylinositol-4-phosphate 5-kinase is considered to be fast and limited primarily by steps that replenishes the PM pool of its substrate, PtdIns4P [18]. However the exact mechanisms by which this resynthetic process is initiated and regulated remains unclear.

Here, we show that our newly developed BRET-based approach is highly sensitive and capable of semiquantitative characterization of inositol lipid changes upon stimulation of cells with agonists of RTK and GPCR. Using this method we found that activation of the RTK epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) or the GPCR type-3 muscarinic receptor (M3R) at a low level not only resulted in the already known PLC-mediated hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2, but also increased the level of PtdIns4P. Using several subtype-specific PI4K inhibitors we show that activation of PI4KA is responsible for this phenomenon, and found to be mediated by the activation of protein kinase C (PKC). Our data thus introduce a robust, sensitive assay for real time readout of PPIn dynamics at the PM, and theoretically also at other individual organelle membranes in live cell populations. This assay reveals a significant increase in the PM PtdIns4P level upon both RTK and GPCR activation, and indicates the role for PKC in the regulation of PPIn re-synthesis at the level of PtdIns4P generation under low level of agonist stimulation, which is probably close to the physiological condition.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Material

Molecular biology reagents were obtained from Fermentas (Vilnius, Lithuania). Cell culture dishes and plates were purchased from Greiner (Kremsmunster, Austria). Coelenterazine h was purchased from Regis Technologies (Morton Grove, IL). Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Rapamycin was obtained from Selleckchem. GeneCellin transfection reagent was from BioCellChallenge (Toulon, France). Atropine was purchased from EGIS (Budapest, Hungary). Unless otherwise stated, all other chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

DNA constructs

Wild type human M3 cholinergic receptor (N-terminal 3x-hemagglutinin tagged) was purchased from S&T cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO). The human EGF receptor was described earlier [19].

To create the various phosphoinositide biosensors, first we created a set of lipid binding domains tagged with either Cerulean (for confocal measurements) or with super Renilla luciferase (for BRET measurements). For this, we used previously characterized domains including PLCδ1-PH-GFP [20], the binding-defective PLCδ1(R40L)-PH-GFP [20], Btk-PH-GFP [21] and GFP-OSH2-2xPH [17]. In addition, we also created the Cerulean- or Luciferase-tagged SidM-2xP4M construct by amplifying the sequences of the P4M domain from the GFP-SidM-P4M construct [22] with a protein linker of SSRE between them, and cloned into the C1 vector using XhoI and EcoRI. Next, similar to other constructs [23] the coding sequence of the PM-targeted Venus in frame with the sequence of the viral T2A peptide was subcloned to 5′ end of the tagged lipid binding domain sequences resulting in the transcription of a single mRNA, which will subsequently lead to the expression of two separate proteins in mammalian cells. For PM targeting of Venus the same sequences were used, what we described in case of FRB (see above).

The low affinity intramolecular Ins(1,4,5)P3 biosensor was described recently [24].

The PM targeted FRB-mRFP and mRFP-FKBP-5ptase constructs used for rapamycin-induced PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion were described earlier [25], with the difference that for PM targeting of the FRB protein we used the N-terminal targeting sequence of mouse Lck protein (MGCVCSSNPENNNN), or the N-terminal targeting sequence of human c-Src protein (MGSSKSKPKDPSQRRNNNN) [26, 27] instead of GAP43 (MLCCMRRTKQVEKNDDDQKI).

mRFP-FKBP-Sac1 was created from mRFP-FKBP-Pseudojanin (PJ) [28] by removing the 5-phosphatase (5-ptase) domain from the construct. For this, it was first digested with KpnI and BamHI, and then the overhanging ends were filled up with Klenow fragment. The final construct resulted in the expression of mRFP-FKBP-tagged yeast Sac1 phosphatase (GeneBank accession number: NM_001179777, residues 2-517) with a small peptide on its C-terminal end (GGSTGSR). In some experiments the mRFP-FKBP-PJ without 5-ptase activity (mRFP-FKBP-PJ-Sac1) was used as 4-phosphatase enzyme [28]. The 5-ptase enzyme of the previously created PM-FRB-mRFP-T2A-mRFP-FKBP-5ptase [23] was replaced with Sac1, PJ and PJ-Sac1 with the difference that L10 was used as PM target instead of Lyn and only the enzymes were fluorescently tagged.

Cell culture

HEK 293T and COS-7 cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Lonza 12-604) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 50 U/ml penicillin and 50 μg/ml streptomycin in a 5% humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C in 10 cm tissue culture plastic dishes.

Bioluminescence Resonance Energy Transfer (BRET) measurements

For BRET measurements HEK 293T cells were trypsinized and plated on poly-lysine-pretreated (0.001%, 1 hour) white 96-well plates at a density of 105 cells/well together with the indicated DNA constructs (0.12–0.3 μg total DNA/well) and the cell transfection reagent (0.5 μl/well Lipofectamine 2000 or 1.5 μl/well GeneCellin). After 6 hours 100 μl/well DMEM containing serum and antibiotics was added. Measurements were performed 24–27 hours after transfection. Before measurements the medium of cells was changed to a medium (50 μl) containing 120 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM CaCl2, 0.7 mM MgSO4, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM Na-HEPES, pH 7.4. Measurements were performed at 37°C using a Mithras LB 940 multilabel reader (Berthold, Germany). The measurements started with the addition of the cell permeable luciferase substrate, coelenterazine h (40 μl, final concentration of 5 μM), and counts were recorded using 485 and 530 nm emission filters. Detection time was 500 ms for each wavelength. The indicated reagents were also dissolved in modified Krebs–Ringer buffer and were added manually in 10 μl. For this, plates were unloaded, which resulted in an interruption in the recordings. All measurements were done in triplicates. BRET ratios were calculated by dividing the 530 nm and 485 nm intensities, and normalized to the baseline.

Since the absolute initial ratio values depended on the expression of the sensors in case of the intermolecular inositol lipid sensors the resting levels were considered as 100%, whereas the 0% was determined from values of those experiments where cytoplasmic Renilla luciferase construct was expressed alone (R=0.874). It is worth to note that this value cannot be reached with the intermolecular sensors even after addition of ionomycin and wortmannin probably because of the non-specific interaction between the cytoplasmic proteins and the small fraction of the uncut T2A proteins (Fig. S1). These experiments also reveal that independently from the expression level the sensors reach the same minimal BRET ratio values within twenty minutes. In case of the PLCδ1-PH this value practically equals to the one of the non-binding sensor indicating the high sensitivity of the sensors to detect the lipids in the low concentration range.

In case of the intramolecular Ins(1,4,5)P3 sensor values are given as I0/I ratios as previously described [24].

Confocal microscopy

HEK 293T or COS-7 cells were cultured on 25 mm No. 1.5 glass coverslips (2×105 cells/35 mm dish) and transfected with the indicated constructs (1–2 μg DNA total/dish) using 2 μl/dish Lipofectamine 2000 for 24 hours. Confocal measurements were performed at 35°C in a modified Krebs-Ringer buffer described above, using a Zeiss LSM 710 scanning confocal microscope and a 63x/1.4 oil-immersion objective. Post-acquisition picture analysis was performed using the Photoshop (Adobe) software to expand to the full dynamic range but only linear changes were allowed.

Western blot

HEK 293T cells were cultured on 6-well plates (5×105 cells/well) and transfected with the indicated constructs (0.5 μg DNA total/well) using 2 μl/well Lipofectamine 2000. Twenty-four hours after transfection the cells were scraped into SDS sample buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors, briefly sonicated, boiled at 95°C for 5 minutes, and separated on SDS-polyacrilamide gel. The proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (anti-GFP from rabbit, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA; and anti-β actin from mouse Sigma, St Louis, MO) and secondary (anti-rabbit or anti-mouse-HRP, Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) antibodies. The antibodies were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence, using Immobilion Western HRP substrate reagents (Millipore, Billerica, MA).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA (analysis of variance) followed by Bonferroni t-test or by two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak test using SigmaStat 3.5 program (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

RESULTS

Creation of biosensors for plasma membrane phosphoinositide detection

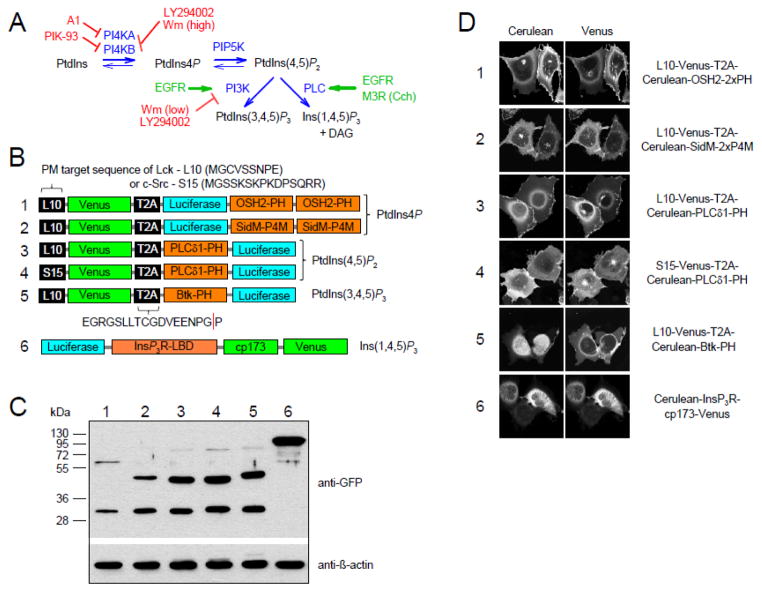

Fig. 1A shows a cartoon depicting the major PPIn changes in the PM and their control by agonists. Most of the studies aiming to follow the inositol lipid alterations upon hormonal stimulations in living cells are based on recordings of fluorescently tagged lipid binding domains by confocal microscopy [29]. However the quantification of changes in such measurements are challenging especially in case of small responses, and many cells have to be imaged in order to see a statistically reliable average response. To overcome this problem, we decided to use non-specific BRET principles [23], and we generated a set of molecular tools capable of following changes of lipid pools in the PM. The lipid recognition specificity of our sensors is based on well-known and already widely-used lipid-binding domains. For PtdIns4P measurements we compared two different peptides previously used as PtdIns4P recognizing domains; the tandem PH domain of OSH2 protein [17] and the recently described P4M domain of the Legionella SidM protein [30]. To increase the PM PtdIns4P detection sensitivity, similar to the OSH2 PH domains, P4M domains were also used as tandems [22]. For PtdIns(4,5)P2 measurement the PH domain of PLCδ1 was used [20], while for phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PtdIns(3,4,5)P3] we used the PH domain of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase, Btk [21]. These PPIn-binding domains were linked to the Renilla luciferase enzyme required for BRET measurements. We also fused these domains to the cyan fluorescence protein, Cerulean for microscopy detection. In order to measure the PM fraction of the various PPIn pools, the energy acceptor Venus was targeted to the PM, using either the first 10 amino acids of Lck (L10) or the first 15 of c-Src (S15), known as PM target sequences [26] (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Characterization of the newly developed energy transfer based phosphoinositide biosensors.

(A) During the synthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2, the PI4K enzymes phosphorylates the PtdIns, and then PIP5K produces PtdIns(4,5)P2 from PtdIns4P. In muscarinic M3 receptor (M3R) expressing HEK 293T cells, PLC activity is stimulated with carbachol (Cch). In EGF receptor expressing cells, EGF stimulus leads to PI3K and PLC activation and thus to the production of PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and Ins(1,4,5)P3 simultaneously. The applied inhibitors are indicated in red.

(B) Schematic representations of domain structures of the different phosphoinositide biosensors. L10 and S15 represent plasma membrane (PM) target sequence of Lck and c-Src, while T2A is a viral protein sequence. The sequence is transcribed as a single mRNA molecule, but translation is interrupted between the two amino acids indicated by the red line, resulting in two separate polypeptide chains.

(C) The biosensors (containing Cerulean instead of luciferase) were expressed in HEK 293T cells, then the fluorescent protein-tagged PM markers and lipid binding domains were resolved by SDS-PAGE, and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-GFP antibodies. Anti-β-actin was used as control. The positions of molecular mass markers are indicated to the left of the Western blot. Numbers above the blot indicate the sensors in the same order as marked on Fig. 1B.

(D) Representative confocal images of COS-7 cells expressing the indicated biosensors. Note that because Cos-7 cells are flat the curvature of the PM around the nucleus can be similar to the nuclear envelope and PM can be misinterpreted as cytoplasm.

For optimal measurements of intermolecular BRET, cells have to express both components (the PM-targeted Venus and the lipid binding domain-fused luciferase) in a constant stoichiometry. Although co-transfection of the two constructs from different plasmids can achieve a constant ratio in a fraction of cells after fine-tuning of the transfection procedures, this is not an easily achievable outcome. To ensure the perfect ratio of co-expression, we created a single plasmid, which contained the coding sequences of both of the proteins separated by the sequence of the viral T2A peptide. During the translation, a molecular cleavage occurs within the T2A peptide, leading to the expression of two separate proteins in equimolar amounts [31]. To test whether cleavage really does occur, HEK 293T cells transiently transfected with the fluorescent sensors (in which luciferase was substituted by Cerulean) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and Western Blot analysis to detect the fragments with an anti-GFP antibody (the Ab recognizes both the Cerulean and Venus-containing fragment). As shown in Fig. 1C the cells expressed mainly the cleaved form of our intermolecular sensors, indicated by the two bands at the appropriate molecular sizes as indicated. Only a very small fraction of the sensors was present in an uncut form. For the detection of cytosolic Ins(1,4,5)P3 concentration we used a recently published intramolecular low affinity BRET sensor based on the ligand binding domain of the type-1 Ins(1,4,5)P3 receptor (Fig. 1B) [24], which appeared as a single band at 99 kDa on the Western Blot (Fig. 1C).

To visualize the intracellular localization of our sensors we performed confocal microscopy in COS-7 cells expressing the indicated fluorescent sensors (Fig. 1D). As reported before, the PLCδ1-PH and the OSH2-2xPH showed clear PM localization in unstimulated cells [20, 32], while the SidM-2xP4M sensors were located to the PM and the Golgi [22], where PtdIns4P levels are considered to be high. The Btk-PH and the InsP3R-LBD were found in the cytosol. As expected, both PM-targeting peptides (L10 and S15) were localized mostly to the PM. Note that as these experiments were carried out in COS-7 cells which are very flat, thus PM localization can be equivocal and easily misinterpreted as cytoplasm. However the clear difference between the cytoplasmic localization of fluorescently tagged Btk-PH and PM-bound L10-Venus makes the interpretation easier.

The two PtdIns4P sensors, OSH2-2xPH and SidM-2xP4M, show a clear difference in their specificity of PtdIns4P recognition

Next we compared the OSH2-2xPH and the SidM-2xP4M probes, both used previously as PtdIns4P reporters, for their specificity and suitability in our system. For this, we selectively changed the level of PtdIns4P using a previously described rapidly inducible PPIn depletion system that is based on the heterodimerization of FKBP (FK506 binding protein 12) and FRB (fragment of mTOR that binds rapamycin) [25]. In this approach, the phosphatase is fused to the FKBP protein, and upon addition of rapamycin the enzyme rapidly translocates to the membrane, where its binding partner, the FRB domain, is targeted.

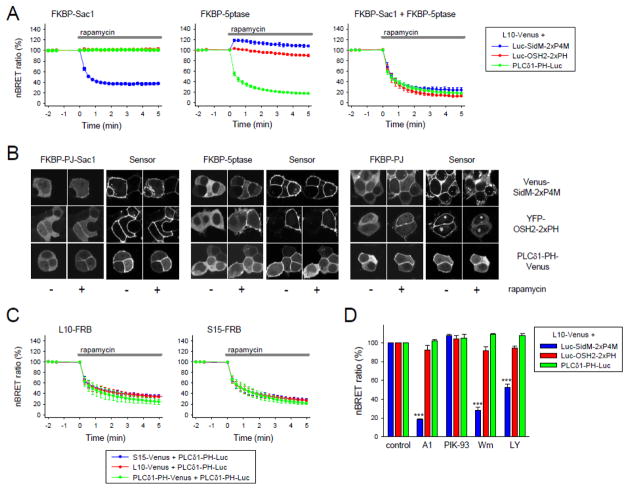

As shown before, PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels, reported by the PLCδ1-PH domain (green traces in Fig. 2A), decreased rapidly when either the 5-phosphatase (5-ptase) enzyme alone or in combination with the Sac1-phosphatase (which has 4-phosphatase activity) was recruited to the PM (Fig. 2A middle and right panels). Recruitment of the Sac1-phosphatase alone to the PM did not cause a decrease in the PLCδ1-PH-generated BRET signal (Fig. 2A left panel). In cells expressing the SidM-2xP4M based biosensor (blue traces), we detected a decrease in the normalized BRET signal upon the recruitment of the Sac1 enzyme (Fig. 2A left). When the 5-ptase was recruited to the PM, the BRET signal from the SidM-2xP4M reporter showed a slight increase consistent with the conversion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 to PtdIns4P (Fig. 2A, middle). Combination of the Sac1 and 5-ptase enzymes again caused a decrease in the SidM-2xP4M-derived BRET signal (Fig. 4A, right). When the same experiments were carried out in cells expressing the OSH2-2xPH containing sensor instead of the SidM-2xP4M (red traces), we obtained different results. Depletion of either PtdIns4P or PtdIns(4,5)P2 failed to cause any change in the BRET signal and it only decreased when both lipids were eliminated from the PM (Fig. 2A right). These results were consistent with previous conclusions that the OSH2-PH domain shows poor discrimination between PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 [33].

Figure 2. Reduction of the PM PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 and their effect on the BRET signal of the indicated biosensors.

(A) The PM PtdIns4P or PtdIns(4,5)P2 pool were decreased with the help of the rapamycin induced heterodimerization assay [25], where Sac1 cleaved the phosphate from the 4′ position and 5-ptase cleaved from the 5′ position of inositol ring. The curves show the changes in the nBRET ratio of the indicated sensors upon addition of 300 nM rapamycin. Values are expressed as percent of the initial BRET ratio measured in untreated cells [mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments]. For the calculation of the nBRET ratio see Materials and Methods.

(B) Representative images of HEK 293T cells expressing the indicated PPIn-binding domains and the enzymes of the rapamycin induced heterodimerization assay that was targeted to L10-FRB (for single cell measurements we used the T2A version of it to make sure that the cells express both proteins of the lipid depletion system [23]). Left columns of each block show the initial localization of the mRFP-tagged enzymes or the Venus-tagged PPIn-binding domains, while the right columns show their localization after 5 minutes treatment with 300 nM rapamycin.

(C) Changes in the nBRET ratio of the different PLCδ1-PH domain containing biosensors, if 5-ptase were targeted to raft (L10-FRB) or non-raft (S15-FRB) regions of the PM. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(D) Effects of 10 minutes incubation with 10 nM A1, 250 nM PIK-93, 10 μM wortmannin (Wm) or 100 μM LY294002 on the nBRET ratio of the different biosensors. Data are means ± SEM of three independent experiments. One-way ANOVA and Bonferrini t-test were made for statistical analysis, ***p<0.001.

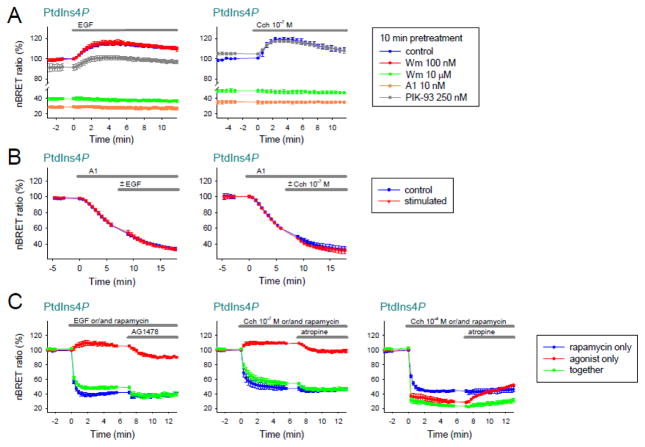

Figure 4. Investigation of the mechanism of agonist-induced PM PtdIns4P elevation.

(A) HEK 293T cells expressing either EGFR or M3R were pretreated with the indicated inhibitors for 10 minutes and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) or Cch (10−7 M). Changes of the PtdIns4P levels were monitored with the BRET PtdIns4P biosensor (SidM-2xP4M). Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(B) HEK 293T cells expressing either EGFR or M3R were treated with A1 (10 nM) for 5 minutes and then with EGF (100 ng/ml) or Cch (10−7 M). Changes of the PtdIns4P levels were monitored with the BRET PtdIns4P biosensor (SidM-2xP4M). Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(C) Cells were transfected with EGFR or M3R, the PtdIns4P biosensor, and the rapamycin induced PtdIns4P depletion system. At time 0, cells got either rapamycin (300 nM) (blue traces) or receptor agonists (EGF 100 ng/ml; Cch 10−7 M or Cch 10−4 M) (red traces) or both (green traces). After 7 minutes EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (10 μM) or M3R competitive antagonist atropine (10 μM) were added. Changes of the PtdIns4P levels were monitored with the BRET PtdIns4P biosensor (SidM-2xP4M). Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

We also performed confocal microscopy in HEK 293T cells transfected with the T2A version of our lipid-depleting system and the fluorescently-tagged lipid-binding domains. In good agreement with the BRET results, recruitment of the Sac1 was required to cause a reduction of the SidM-2xP4M signal in the PM (Fig. 2B left, upper row) (note that the SidM-2xP4M construct released from the PM rapidly associates with some intracellular organelles masking its cytosolic increase). Upon 5-ptase recruitment, the PLCδ1-PH became cytoplasmic (Fig. 2B middle, bottom row), but there was no change in the intracellular localization of OSH2-2xPH and the slight increase in the PM-bound SidM-2xP4M could not be detected (Fig. 2B middle, middle and upper rows, respectively). As expected, all of the sensors became cytoplasmic, when both the 4-ptase Sac1 and 5-ptase were targeted together to the PM (Fig. 2B right).

The PM targeting sequence (L10) used in the above studies is considered to provide PM targeting to “rafts” [27]. It contains a sequence that is both myristoylated and palmitoylated. The N-terminal c-Src sequence (S15) is also myristoylated but contains several basic residues instead of palmitoylation, and has been claimed to be excluded from “rafts” [27]. Therefore, we investigated whether the effect of the 5-ptase recruitment on PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion depends on the sequence that is used for PM targeting. We compared the use of L10-FRB and S15-FRB on the effects of 5-ptase recruitment on PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion. To detect PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools we also paired our PtdIns(4,5)P2 luciferase sensor with three different PM-targeted Venus constructs (L10, S15 or PLCδ1-PH) for comparisons. As shown on Fig. 2C, there was no difference between the signals regardless of which targeting sequence was used. It is also noteworthy that using the PLCδ1-PH both as the PM target sequence for Venus and the luciferase-fused reporter showed a similar BRET ratio change seen with the L10 or S15 sequence. Similar results were found when the expression level of our constructs were decreased or experiments were performed in other cell lines (COS-7, HeLa) (data not shown). Thus, the nBRET ratio changes under our experimental conditions did not depend on where the 5-ptase enzymes were targeted in the PM, or whether both the donor and acceptor or only the donor has dissociated from the PM.

To investigate whether cholesterol depletion, that reduces the amount of the liquid ordered domains, has any influence on the signals, PtdIns(4,5)P2 measurement was performed after 30 min pretreatment with 10 mM methyl-beta-cyclodextrin (MβCD) [34]. We found that it drastically decreased the initial BRET ratio measured by either the L10-Venus-T2A-PLCδ1-PH-Luc or the S15-Venus-T2A-PLCδ1-PH-Luc to the level that is found after complete PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion with 10 μM ionomycin (Fig. S2A) [20]. When performing confocal microscopy measurements, we found that MβCD pretreatment did not cause the PM disappearance of the PLCδ1-PH-Cerulean indicating that MβCD does not affect the PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 level (Fig. S2B). Since this MβCD pretreatment also left the Venus-tagged L10 or S15 at the PM (Fig. S2B), the decrease of the BRET ratio must have been caused by changing the membrane in such a manner that efficient BRET could not take place. As we could not detect any microdomain-related differences between the L10 and S15 containing anchors and sensors, the L10 target sequence was used in subsequent experiments.

Next we examined the effects of different PI4K inhibitors on the translocation of the aforementioned sensors. For this, we used pretreatment with the recently published PI4KA-specific inhibitor (A1 compound) at 10 nM concentration [35]. For PI4KB inhibition, we used 250 nM PIK-93 [36], and we also used wortmannin (Wm) at 10 μM and LY294002 at 100 μM as non-selective type III PI4K inhibitors [37]. For controls we used the BRET ratio that was measured in cells treated with DMSO. As shown on Fig. 2D, 10 min pretreatment with 10 nM A1, 10 μM Wm and 100 μM LY294002 caused a robust and significant decrease (p<0.001, one-way ANOVA analysis, where the investigated factor was the effect of enzyme inhibitors compared to the control vehicle treated cells, followed by Bonferroni t-test which lets multiple comparisons versus control group) in the signal from SidM-2xP4M, while those from OSH2-2xPH and PLCδ1-PH were not affected (p≥0.05). Pretreatment with 250 nM PIK-93 did not cause any change in the BRET ratio from any of the sensors. Since this compound mainly inhibits PI4KB, which primarily controls Golgi PtdIns4P levels, its impact on the PM PtdIns4P level is minimal at best [17]. Taken together, all of these data suggest that SidM-2xP4M is the probe of choice for reliable detection of PM PtdIns4P levels and caution should be used when utilizing the OSH2-2xPH for this purpose. Therefore, in the following experiments we used SidM-2xP4M as PtdIns4P sensor.

Agonist-induced changes of the PPIns upon stimulation of EGF and type-3 muscarinic receptors

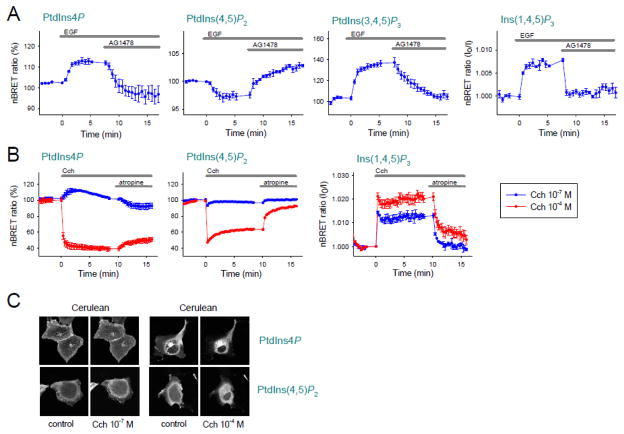

Next we followed the dynamic changes of the various PM PPIns upon hormonal stimulation. For this, we chose the tyrosine kinase EGFR, known to activate both phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and PLCγ, and the G protein-coupled M3R, which activates PLCβ (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig. 3A, supra maximal activation of EGFR with 100 ng/ml epidermal growth factor (EGF) [38] caused a rapid increase in PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 reflecting PI3K activation (Fig. 3A second to right panel). Activation of PLC was reflected in a small decrease in PtdIns(4,5)P2 and an increase in Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels (Fig. 3A second to left and right panels, respectively). Surprisingly, we found that the PM PtdIns4P level also showed a substantial increase (Fig. 3A left panel). All of these effects were reversible by the potent tyrosine kinase inhibitor AG1478 (10 μM) [39].

Figure 3. Changes in the PM phosphoinositide levels upon EGF or carbachol stimulation.

(A and B) Normalized BRET ratios corresponding to PM PtdIns4P, PtdIns(4,5)P2 PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and cytoplasmic Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels are shown upon EGF (100 ng/ml) (A) or carbachol stimulation (10−7 or 10−4 M) (B). HEK 293T cells transiently express EGFR or M3R and the different biosensors [SidM-2xP4M for PtdIns4P, PLCδ1-PH for PtdIns(4,5)P2, Btk-PH for PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and InsP3R-LBD for Ins(1,4,5)P3]. After 8 minutes EGFR inhibitor AG1478 (10 μM) or M3R competitive antagonist atropine (10 μM) were added. In case of the Ins(1,4,5)P3 sensor, I0/I nBRET ratio were calculated as described previously [24]. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(C) Representative confocal images of COS-7 cells expressing the Cerulean version of biosensors used on Panel B. Images show the localization of the PPIn binding domains before (left columns) and 5 min after carbachol (10−7 or 10−4 M) stimulation (right columns).

When M3R expressing cells were stimulated with 100 μM carbachol (Cch), a concentration widely used in in vivo experiments [40], a robust decrease in both the PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 was observed with a concomitant increase in Ins(1,4,5)P3 (Fig. 3B red traces). Addition of 10 μM atropine (a M3R competitive antagonist) caused a quick return of Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels toward baseline and a quick resynthesis of the PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools, Notably, reduced PtdIns4P level showed only a slower increase after termination of Cch action with atropine, perhaps because of its rapid conversion to PtdIns(4,5)P2. Since Cch stimulation causes a much more robust PLC activation than EGF, we wanted to evaluate lipid changes after stimulation by lower concentrations of Cch where the PLC activation is more comparable to those evoked by EGF. Lowering the concentration of Cch to 100 nM, we detected similar Ins(1,4,5)P3 increases and PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion as with EGF and at this low concentration of Cch, PtdIns4P also showed an increase that was reversed with atropine (Fig. 3B blue traces).

We also wanted to detect the same changes in the PPIn pools in COS-7 cells with confocal microscopy, using the Cerulean containing PPIn sensors. Fig. 3C shows the sensor localization in resting condition and 5 min after carbachol stimuli (figure shows only the Cerulean-tagged PPIn-binding domains since no changes occurred in the intracellular localization of L10-Venus). When stimulating M3R with 10−7 M Cch the movement of the Cerulean-SidM-2xP4M and the Cerulean-PLCδ1-PH was hard to evaluate, but massive hormonal stimulus (10−4 M Cch) caused an easily detectable translocation of the PPIn-binding domains. These examples clearly demonstrated the advantage of the BRET approach as it detected even the small changes in the lipid pools that were hard to evaluate with simple imaging.

The hormone induced elevation of the plasma membrane PtdIns4P level is caused by activation of PI4KA

To investigate which PI4K enzyme(s) are important in the agonist-induced increase in PtdIns4P upon stimulation with EGF or low concentration of carbachol, we pretreated cells expressing either the EGFR or the M3R together with the PtdIns4P sensor with various PI4K inhibitors. As shown on Fig. 4A, inhibition of PI3Ks with low concentration of Wm (100 nM) or inhibition of PI4KB with 250 nM PIK-93 did not prevent the EGF or carbachol induced elevation of PtdIns4P (Fig. 4A; red, gray and blue traces). In contrast, application of PI4KA specific inhibitor 10 nM A1 or using 10 μM Wm (10 min), which inhibits all PI3Ks and also type III PI4Ks greatly reduced the PtdIns4P levels even before stimulation and prevented the elevation of PtdIns4P upon stimulation (Fig. 4A green and orange traces). Since A1 pretreatment causes a decrease in PtdIns4P levels even without stimulation, we also tested the effects of the agonists on PtdIns4P levels at earlier time points after A1 addition when there was still a substantial amount of PtdIns4P in the PM. As shown on Fig. 4B, application of the agonist caused no increase in PtdIns4P levels when PI4KA was inhibited clearly implicating PI4KA in the hormone-induced elevation of PtdIns4P.

The increase of PtdIns4P synthesis upon hormonal stimulation is directly regulated by receptor activation

In order to determine whether agonists can increase PtdIns4P synthesis at various levels of PtdIns4P, we investigated the effects of the agonists during Sac1-induced PtdIns4P depletion. As shown on Fig. 4C, rapamycin-induced Sac1 recruitment caused a drop of PtdIns4P levels, but this decrease was somewhat smaller when the cells were also stimulated by EGF or low concentration of Cch (Fig. 4C compare blue vs. green traces). This difference was eliminated upon termination of the agonist action either with AG1478 (for EGF) or atropine (for Cch). This result suggested that agonist stimulation increased the formation of PtdIns4P even against a larger consumption of the lipid by the recruited Sac1 phosphatase indicating that not or not only the decreased PtdIns4P level can activate the resynthesis. When high concentration of Cch is used, PLC activation is so robust that it causes a decrease in PtdIns4P as the lipid is drained via PtdIns(4,5)P2. Under these conditions the stimulatory effect of the agonists on PtdIns4P formation is masked by its high consumption rate by conversion to PtdIns(4,5)P2 (Fig. 4C, right panel).

PKC plays an important role in the activation of PI4KA upon hormonal stimulation

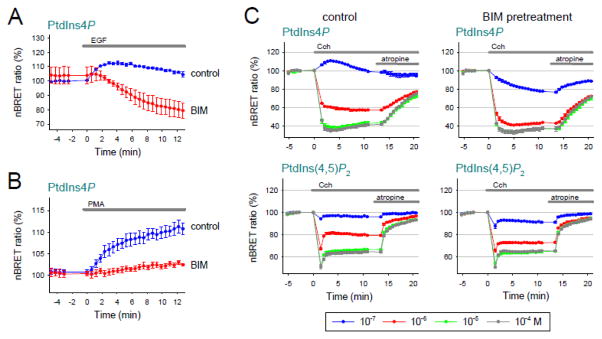

Next we explored the mechanism(s) by which agonists increase PI4KA activity. One of the common elements between RTK and GPCR stimulation is the activation of PLC with generation of Ins(1,4,5)P3 and DAG. [Since 100 nM wortmannin, which inhibits the PI3K enzymes, completely blocked PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 production, but had no effect on the EGF induced Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal (Fig. S3), the PtdIns(3,4,5)P3-AKT pathway does not seem to be uniquely important in this process]. First, we attempted to inhibit PLC activation, but unfortunately neither U73122, nor edelfosine has proven to be useful in our system. While pretreatment of the HEK 293T cells with U73122 (10 μM 10 min) failed to inhibit the hormone-induced Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal, edelfosine pretreatment (10 μM 30 min) appeared to be too toxic, altering the PPIn levels in the PM resulting in the reduction of the lipids [PtdIns4P, PtdIns(4,5)P2] monitored by the lipid sensors in BRET assays and causing the rounding up of cells in confocal microscope as reported earlier [41] (data not shown). Next we tested whether inhibition of PKC, the next enzyme of the signaling cascade has an effect on the PtdIns4P increase. As shown on Fig. 5A, pretreatment of the cells with bisindolylmaleimide (BIM), a pan PKC inhibitor (2 μM 10 min) [42] did not cause any change in the basal level of PM PtdIns4P, but completely abolished its EGF-evoked increase. Pretreatment with RO318425 (1 μM 10 min) another PKC inhibitor had similar effect (data not shown). Conversely, 100 nM PMA, activator of PKC induced a modest elevation in PtdIns4P levels that was completely prevented by BIM pretreatment (Fig. 5B). These results suggested that PKC plays an important role in the maintenance of PtdIns4P pools in the PM upon RTK activation.

Figure 5. The role of PKC in the increasing PM PtdIns4P levels and in the maintenance of PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 upon hormonal stimulation.

(A) BRET measurement with the PtdIns4P biosensor (SidM-2xP4M) in HEK 293T cells expressing EGFR. 10 minutes incubation with BIM (2 μM) was used to block PKC activity (red curve) while control cells got vehicle medium (blue curve). At time 0, cells were treated with 100 ng/ml EGF. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(B) In a similar experiment, instead of the hormonal stimulus the cells were stimulated with PMA (1 μM) to activate PKC. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

(C) Simultaneous measurement of PM PtdIns4P (with SidM-2xP4M) and PtdIns(4,5)P2 (with PLCδ1-PH) levels with our BRET biosensors in HEK 293T cells expressing M3R. Left panels show the changes of the lipid levels under control circumstances while right panels demonstrate the nBRET changes in those cells which were pretreated with BIM (2 μM, 10 min). Four different concentrations of Cch (10−7 M, 10−6 M, 10−5 M and 10−4 M Cch) were used as hormonal stimuli and are shown in blue, red, green and grey respectively. 12 minutes later all cells got 10 μM atropine. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

To further evaluate the importance of this PKC-induced increase of PM PtdIns4P we examined the effect of BIM pretreatment on the Cch-activated signaling pathway. As shown on Fig. 5C, BIM pretreatment also abolished the increase of PM PtdIns4P when cells were stimulated with low concentration of Cch (10−7M). Although higher dose of Cch (10−6 M) decreased PtdIns4P levels, comparing the responses of control and BIM pretreated cells, clearly indicates that a PKC-induced PI4K activation is important in the replenishment of PtdIns4P upon receptor activation. Parallel measurements of PtdIns(4,5)P2 reveal that this effect of PKC inhibition is also reflected in the change of the PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools. Noteworthy, BIM pretreatment did not alter the resynthesis of PM PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 after the termination of receptor activity. Interestingly, BIM pretreatment did not affect the Cch-evoked Ins(1,4,5)P3 response in the same concentration range (10−7–10−4 M) (data not shown).

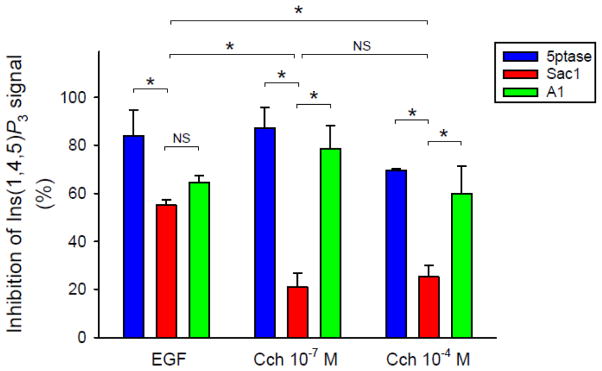

The resynthesis of PM PtdIns4P rather than its pool size is important for sustained Ins(1,4,5)P3 production upon hormonal stimulation

Lastly, we wanted to investigate the role of PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns4P in the signal transduction of EGFR and M3R. For this purpose we depleted either PtdIns(4,5)P2 or PtdIns4P at the PM with the rapamycin-induced recruitment of 5-ptase or Sac1 enzyme and stimulated the cells with EGF or carbachol. We measured Ins(1,4,5)P3 levels and looked for the impact of depleting the respective lipids on Ins(1,4,5)P3 formation. Fig. 6 shows that as expected, depletion of PtdIns(4,5)P2 by a recruited 5-ptase measured 5 min after the rapamycin treatment almost completely abolished the agonist-evoked Ins(1,4,5)P3 production (Fig. 6 blue columns). Kinetic curves of these experiments are shown on Fig. S4. Reducing the levels of PtdIns4P by Sac1 recruitment had only a moderate effect on the subsequent Ins(1,4,5)P3 response (Fig. 6 red columns). Pretreatment of the cells with A1, which depletes PM PtdIns4P via inhibiting the resynthesis of PtdIns4P, had a strong inhibitory effect on Ins(1,4,5)P3 formation (Fig. 6 green columns). Statistical analysis revealed that depleting the PtdIns(4,5)P2 pool of the PM or inhibiting the synthesis of PtdIns4P by A1 had a significantly higher impact on the Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal comparing to Sac1 recruitment in case of M3R signaling (p<0.05, we performed two-way ANOVA analysis, where one factor is the hormonal stimulus, while the other is the form of inhibition. To compare the results all pairwise multiple comparisons were performed by the Holm-Sidak method.). These findings are in good agreement with an earlier report suggesting that maintenance of PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools during agonist stimulation can be achieved even at reduced PtdIns4P levels as long as the PI4KA enzyme is able to synthesize PtdIns4P at the PM [28]. However, in case of EGF evoked Ins(1,4,5)P3 elevation, there was no statistically significant difference between the inhibitory effects of the Sac1-evoked PtdIns4P depletion and the A1 treatment, which also means that EGFR signaling is more sensitive to the PM PtdIns4P depletion (caused by Sac1 recruitment) compared to M3R (p<0.05, two-way ANOVA analysis followed by Holm-Sidak test).

Figure 6. The role of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 in maintaining the hormone-induced Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal.

Cells expressing EGFR or M3R, the Ins(1,4,5)P3 biosensor and the heterodimerization based lipid depletion system, which contained either mRFP-tagged Sac1 or 5-ptase. The cells were first stimulated with the indicated concentration of hormones. In 6 minutes 300 nM rapamycin or 10 nM A1 were added to the cells. For the individual curves see Fig. S4. The graph shows the percentage of the inhibition of Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal, measured at 5 or 10 minutes after the addition of rapamycin or A1, respectively. Note, that the inhibition is plotted and not the response. Values are means ± SEM of three independent experiments, two-way ANOVA and Holm-Sidak post hoc test were made for statistical analysis, *p<0.05, NS means not significant.

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to develop and use bioluminenscence resonance energy based biosensors for measuring population dynamics of different PPIns in the PM upon hormonal stimulation. The BRET principle can be used in the form of an intramolecular sensor, where the fluorescently (Venus) tagged lipid binding module is linked to the donor (luciferase). Such intramolecular sensors sense the conformational change induced by ligand binding by changing the distance or orientation between the luciferase and Venus molecules. We created such a sensor for measuring the Ins(1,4,5)P3 in the cytoplasm, as discussed previously [24]. For following lipid dynamics, however, a larger signal can be expected when two separated molecules are linked to the donor or acceptor proteins. The feasibility of this technique in PPIn detection was shown previously in case of FRET [43, 44] and BRET measurements [23]. In this case, the level of energy transfer is determined mainly by the distance between the constructs. To specifically measure changes only in the PM fraction of the PPIn pools, we targeted the acceptor fluorescent protein to the PM with the help of a short sequence derived from either Lck or Src [26]. The inositol lipid-dependent PM binding of the luciferase linked to the lipid binding domain provided the basis for the non-specific BRET signal generated at the PM. A similar approach was used previously to measure PM PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 [45], but in that study the co-expression of the BRET pair was provided by the generation of a double stable clone of MCF-7 cells allowing the measurement of the lipid pool shown by Akt-PH, which is known to bind both PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 and PtdIns(3,4)P2 [46, 47]. Intermolecular BRET applications become more reliable if the donor and the acceptor molecules are expressed in constant stoichiometric amounts, which is difficult to achieve with co-transfection. Thus we created single plasmids suitable for the cellular expression of both proteins in equimolar amounts with the help of the viral T2A peptide, which displays a “self-cleaving” property [31]. Using this technique we were able to achieve complete co-transfection of the cells in a convenient way.

To monitor the PtdIns4P content specifically at the PM we compared two sensors, which contained the tandem forms of either the OSH2-PH or SidM-P4M. These probes have been introduced to monitor PM PtdIns4P, while other PtdIns4P sensors, such as the Fapp1- or OSBP-PH domains are biased toward the Golgi pool of these lipids. Using selective or combined depletion of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 by recruitable lipid phosphatases, we demonstrated the superiority of the SidM-P4M domain over the OSH2-PH domain, the latter also binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2, a conclusion also reached recently [28].

We also considered the notion that subdomains within the PM (rafts and non-rafts) may have different enrichments of PPIns as suggested by several studies (e.g. [8, 30, 48]) Therefore, we compared targeting of the acceptor Venus to different microdomains in the PM using either the N-terminal PM targeting sequence of Lck (L10) or c-Src (S15), which have been shown to separately modify PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels in various PM microdomains, when used to recruit a 5-ptase enzyme to the PM [27]. However, our studies failed to detect any difference in the kinetics or amplitude of the PtdIns(4,5)P2 signals after agonist stimulation or 5-ptase recruitment when comparing the two different targeting sequences used with the PtdIns(4,5)P2 sensor. This can be caused by the overexpression of our sensors and PPIn-depleting systems; however, we did not see any differences between the PM microdomain targets when we decreased the expression level even to the detection limit. We also performed the experiments in different cell lines (HEK 293T, COS-7, HeLa), but it had no impact on the obtained results. Disruption of the microdomain organization of the PM by cholesterol depletion did not resulted in the cytoplasmic translocation of neither the L10-Venus and S15-Venus constructs nor the PtdIns(4,5)P2 specific PLCδ1-PH domain in confocal measurements. In contrast, after the MβCD pretreatment even basal BRET ratio values decreased to a very low level in case of both L10- and S15-containing PtdIns(4,5)P2 sensors. There is a possibility that labeling the targeting sequences disrupted their PM microdomain localization and that initially the PtdIns(4,5)P2 (and thus the PLCδ1-PH) and the PM-targeted Venus were localized to the same microdomains but later the disruption of the liquid ordered and disordered domains caused equal distribution of all tagged molecules, which resulted in decreased BRET signal. Unfortunately, as the size of microdomains is considered to be below the resolution of confocal microscopy, we could not prove this theory. Our conclusion regarding the microdomain-specific PPIn detection is that even if there are steady-state differences between the distribution of inositol lipids within the PM, lateral diffusion and rapid exchange between these domains make the lipids accessible to PLC or phosphatase enzymes regardless of the targeting domains used for their detection or manipulation.

The major advantage of the BRET approach was its sensitivity and reporting on a large number of cells that allowed reliable detection of small changes that are easily overlooked in imaging experiments. This helped us uncover a small but consistent increase in PtdIns4P levels after EGF stimulation or when cells were stimulated by low concentrations of Cch. Robust activation of PLC by GPCRs is usually associated with a decrease in both PtdIns(4,5)P2 and PtdIns4P leading to the general conclusion that PtdIns4P levels only passively follow the PtdIns(4,5)P2 changes, simply following the law of mass action. The small but reproducible increase in PtdIns4P levels revealed by BRET measurements and apparent only at modest PLC activation, clearly suggested a more active regulation of PtdIns4P synthesis in the PM. Several early studies have shown PPIn kinase activation after EGFR stimulation and association of the kinase activity with EGF receptors [49, 50]. Some of these activities turned out to be PI3Ks, while others were attributed to the type II PI4K enzymes [51]. Our studies using specific inhibitors of type III PI4Ks, and even subtype-specific ones clearly identified PI4KA as the enzyme that is activated during agonist stimulation. Such agonist-induced activation of PI4KA was apparent even when PtdIns4P levels were reduced by a recruitable Sac1 enzyme.

The fact that both GPCRs and EGF receptors were able to elevate PtdIns4P levels indicated that the kinase may be activated as a consequence of PLC action, which drew our attention to PKC. Indeed, inhibition of PKC by two different pan-PKC inhibitors was able to prevent the agonist-induced increase in PtdIns4P levels. Importantly, PKC inhibition by BIM did not decrease the basal levels of PM PtdIns4P, which was in contrast to the inhibition of the PI4KA by A1. Similarly, after termination of the more robust Cch response by atropine, reduced PtdIns4P levels started to recover even after BIM treatment, suggesting that PKC inhibition is not affecting basal PI4KA activity, it only interferes with the agonist-induced boost that helps maintain PM phosphoinositide levels.

There are few papers in the literature, which have already suggested a possible coupling between the downstream signaling of PKC and some PI4Ks. In a recent study using TLC and prolonged hormonal stimulation (2–24 h), it was found that activation of Gq-coupled receptor not only initiated the hydrolysis of PtdIns(4,5)P2 but simultaneously increased resynthesis of PtdIns(4,5)P2, by a mechanism that involved PKC and PI4KB [52]. Although there is some evidence that the Golgi pool of PtdIns4P made by PI4KB contributes to PM PtdIns(4,5)P2 levels [53, 54], our present and previous experiments [17, 35] showed no indication of PI4KB involvement in PM PtdIns4P or PtdIns(4,5)P2 maintenance. In another study, using the OSBP-PH and Fapp1-PH to monitor the PM PtdIns4P content in β-cells, some very similar conclusions were made regarding the GPCR induced PtdIns4P elevation and its possible coupling to PKC mediated PI4KA activation [40]. However there are also some contradictions between this paper and our findings, as they could not detect any increase of PM PtdIns4P in case of RTK activation (using insulin as substrate). Moreover, using the same 100 μM Cch as ligand of M3R, we found a decreased PtdIns4P in the PM, and only in case of low concentration of agonist stimuli – which is possibly closer to the physiological one – we could detect its elevated level. One possible explanation for these discrepancies can be that OSBP-PH and Fapp1-PH are mostly Golgi localized as they work as co-incidence detectors which means they do not only need PtdIns4P but also the presence of Arf1 to bound to membranes [55], and only a very small fraction of these sensor binds PtdIns4P in the PM [56]. Although this fraction was separated using TIRF microscopy the reliability of OSBP-PH and Fapp1-PH as PM PtdIns4P sensors is questionable. There is a possibility that some changes in the Golgi after receptor stimulus, especially using maximal agonist concentration, can alter the biosensors’ localization, and the translocation of the biosensor from the Golgi to the PM does not necessarily mean increased PtdIns4P in the PM but also a decrease in the Golgi. Using biosensors with excellent specificity and affinity for PtdIns4P such as SidM-P4M [33] can solve these problems, and can make us capable to detect such small changes in the lipid’s level in the PM as caused by 100 ng/ml EGF or 100 nM Cch.

Lastly, we wanted to investigate the importance of the size of the PM PtdIns4P pool in the maintenance of PtdIns(4,5)P2 pools and generation of Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal during PLC stimulation. It was reported recently that PtdIns(4,5)P2 synthesis can be maintained with greatly reduced levels of PM PtdIns4P [28]. Our experiments showed that pharmacological PI4KA inhibition and PtdIns(4,5)P2 depletion by recruited 5-ptase equally inhibited the Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal but reducing PtdIns4P level by Sac1 recruitment caused only a modest reduction of Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal in M3R activated cells. These data collectively suggested that PM PtdIns4P synthesis is critical for PtdIns(4,5)P2 maintenance upon GPCR activation, which, however, can occur even at a very much diminished PtdIns4P pool size. However, upon EGFR stimulation the Ins(1,4,5)P3 signal was more sensitive to the Sac1 caused PtdIns4P depletion, suggested by the significant elevation of the inhibitory effect. This raise the possibility of different substrate pool needs of the different type of receptors, however to identify the exact background of this phenomenon needs further investigation.

In summary, we present a BRET-based tool-set for the sensitive detection of PPIns changes in populations of live cells. Using these tools to characterize the PPIns changes in the PM in agonist-stimulated cells we uncovered augmentation of PI4KA during PLC activation that is mediated by PKC. Further studies are on their way to identify the exact PKC isoform and the mechanism of PI4KA activation.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Development of a BRET-based tool-set to monitor PPIn dynamics in live cells

EGFR and moderate M3R activation leads to increased PtdIns4P level at the PM

RTK and GPCR stimulation can lead to PI4KA activation through a PKC-dependent manner

PM PtdIns4P synthesis is critical for Ins(1,4,5)P3 signaling upon receptor activation

Acknowledgments

P.V. was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (NKFI K105006). T.B. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health. G.H. is supported by funds from the Department of Cell Biology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The technical assistance of Kata Szabolcsi is highly appreciated.

ABBREVIATION LIST

- DAG

diacylglycerol

- PPIn

phosphoinositides

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- Ins(1,4,5)P3

inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- PM

plasma membrane

- BRET

bioluminescence resonance energy transfer

- PLC

phospholipase C

- PtdIns(4,5)P2

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- PtdIns4P

phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate

- PI4K

phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- M3R

type-3 muscarinic receptor

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PtdIns(3,4,5)P3

phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate

- L10

the first 10 amino acids of Lck

- S15

the first 15 amino acids of c-Src

- FKBP

FK506 binding protein 12

- FRB

fragment of mTOR that binds rapamycin

- 5-ptase

5-phosphatase

- MβCD

methyl-beta-cyclodextrin

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- Cch

carbachol

- BIM

bisindolylmaleimide

- PJ

Pseudojanin

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Sasaki T, Takasuga S, Sasaki J, Kofuji S, Eguchi S, Yamazaki M, Suzuki A. Mammalian phosphoinositide kinases and phosphatases. Prog Lipid Res. 2009;48:307–343. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balla T. Phosphoinositides: tiny lipids with giant impact on cell regulation. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:1019–1137. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berridge MJ. Inositol trisphosphate and diacylglycerol as second messengers. Biochem J. 1984;220:345–360. doi: 10.1042/bj2200345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Di Paolo G, De Camilli P. Phosphoinositides in cell regulation and membrane dynamics. Nature. 2006;443:651–657. doi: 10.1038/nature05185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Traynor-Kaplan AE, Harris AL, Thompson BL, Taylor P, Sklar LA. An inositol tetrakisphosphate-containing phospholipid in activated neutrophils. Nature. 1988;334:353–356. doi: 10.1038/334353a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kielkowska A, Niewczas I, Anderson KE, Durrant TN, Clark J, Stephens LR, Hawkins PT. A new approach to measuring phosphoinositides in cells by mass spectrometry. Adv Biol Regul. 2014;54:131–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golebiewska U, Kay JG, Masters T, Grinstein S, Im W, Pastor RW, Scarlata S, McLaughlin S. Evidence for a fence that impedes the diffusion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate out of the forming phagosomes of macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:3498–3507. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-02-0114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammond GR, Schiavo G, Irvine RF. Immunocytochemical techniques reveal multiple, distinct cellular pools of PtdIns4P and PtdIns(4,5)P(2) Biochem J. 2009;422:23–35. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Balla T, Varnai P. Visualization of cellular phosphoinositide pools with GFP-fused protein-domains. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2009;Chapter 24(Unit 24):24. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb2404s42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Varnai P, Balla T. Live cell imaging of phosphoinositides with expressed inositide binding protein domains. Methods. 2008;46:167–176. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2008.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu SL, Sheng R, O’Connor MJ, Cui Y, Yoon Y, Kurilova S, Lee D, Cho W. Simultaneous in situ quantification of two cellular lipid pools using orthogonal fluorescent sensors. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2014;53:14387–14391. doi: 10.1002/anie.201408153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon Y, Lee PJ, Kurilova S, Cho W. In situ quantitative imaging of cellular lipids using molecular sensors. Nat Chem. 2011;3:868–874. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaya H, Patton GM, Hong SL. Bradykinin-induced activation of phospholipase A2 is independent of the activation of polyphosphoinositide-hydrolyzing phospholipase C. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:4972–4977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willars GB, Nahorski SR, Challiss RA. Differential regulation of muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-sensitive polyphosphoinositide pools and consequences for signaling in human neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5037–5046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu C, Watras J, Loew LM. Kinetic analysis of receptor-activated phosphoinositide turnover. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:779–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200301070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakanishi S, Catt KJ, Balla T. A wortmannin-sensitive phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase that regulates hormone-sensitive pools of inositolphospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:5317–5321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balla A, Kim YJ, Varnai P, Szentpetery Z, Knight Z, Shokat KM, Balla T. Maintenance of hormone-sensitive phosphoinositide pools in the plasma membrane requires phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase IIIalpha. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:711–721. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falkenburger BH, Jensen JB, Hille B. Kinetics of PIP2 metabolism and KCNQ2/3 channel regulation studied with a voltage-sensitive phosphatase in living cells. J Gen Physiol. 2010;135:99–114. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varnai P, Bondeva T, Tamas P, Toth B, Buday L, Hunyady L, Balla T. Selective cellular effects of overexpressed pleckstrin-homology domains that recognize PtdIns(3,4,5)P3 suggest their interaction with protein binding partners. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4879–4888. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Varnai P, Balla T. Visualization of phosphoinositides that bind pleckstrin homology domains: calcium- and agonist-induced dynamic changes and relationship to myo-[3H]inositol-labeled phosphoinositide pools. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:501–510. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.2.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varnai P, Rother KI, Balla T. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent membrane association of the Bruton’s tyrosine kinase pleckstrin homology domain visualized in single living cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10983–10989. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hammond GR, Machner MP, Balla T. A novel probe for phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate reveals multiple pools beyond the Golgi. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:113–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201312072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toth DJ, Toth JT, Gulyas G, Balla A, Balla T, Hunyady L, Varnai P. Acute depletion of plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate impairs specific steps in endocytosis of the G-protein-coupled receptor. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:2185–2197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.097279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulyas G, Toth JT, Toth DJ, Kurucz I, Hunyady L, Balla T, Varnai P. Measurement of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate in living cells using an improved set of resonance energy transfer-based biosensors. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0125601. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Varnai P, Thyagarajan B, Rohacs T, Balla T. Rapidly inducible changes in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels influence multiple regulatory functions of the lipid in intact living cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:377–382. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodgers W. Making membranes green: construction and characterization of GFP-fusion proteins targeted to discrete plasma membrane domains. BioTechniques. 2002;32:1044–1046. 1048, 1050–1041. doi: 10.2144/02325st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnson CM, Chichili GR, Rodgers W. Compartmentalization of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate signaling evidenced using targeted phosphatases. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:29920–29928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805921200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hammond GR, Fischer MJ, Anderson KE, Holdich J, Koteci A, Balla T, Irvine RF. PI4P and PI(4,5)P2 are essential but independent lipid determinants of membrane identity. Science. 2012;337:727–730. doi: 10.1126/science.1222483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wuttke A, Idevall-Hagren O, Tengholm A. Imaging phosphoinositide dynamics in living cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;645:219–235. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-175-2_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brombacher E, Urwyler S, Ragaz C, Weber SS, Kami K, Overduin M, Hilbi H. Rab1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor SidM is a major phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate-binding effector protein of Legionella pneumophila. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4846–4856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807505200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szymczak AL, Workman CJ, Wang Y, Vignali KM, Dilioglou S, Vanin EF, Vignali DA. Correction of multi-gene deficiency in vivo using a single ‘self-cleaving’ 2A peptide-based retroviral vector. Nature biotechnology. 2004;22:589–594. doi: 10.1038/nbt957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roy A, Levine TP. Multiple pools of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate detected using the pleckstrin homology domain of Osh2p. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44683–44689. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401583200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hammond GR, Balla T. Polyphosphoinositide binding domains: Key to inositol lipid biology. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1851:746–758. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zacharias DA, Violin JD, Newton AC, Tsien RY. Partitioning of lipid-modified monomeric GFPs into membrane microdomains of live cells. Science. 2002;296:913–916. doi: 10.1126/science.1068539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bojjireddy N, Botyanszki J, Hammond G, Creech D, Peterson R, Kemp DC, Snead M, Brown R, Morrison A, Wilson S, Harrison S, Moore C, Balla T. Pharmacological and genetic targeting of the PI4KA enzyme reveals its important role in maintaining plasma membrane phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate and phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate levels. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6120–6132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.531426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knight ZA, Gonzalez B, Feldman ME, Zunder ER, Goldenberg DD, Williams O, Loewith R, Stokoe D, Balla A, Toth B, Balla T, Weiss WA, Williams RL, Shokat KM. A pharmacological map of the PI3-K family defines a role for p110alpha in insulin signaling. Cell. 2006;125:733–747. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Downing GJ, Kim S, Nakanishi S, Catt KJ, Balla T. Characterization of a soluble adrenal phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase reveals wortmannin sensitivity of type III phosphatidylinositol kinases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:3587–3594. doi: 10.1021/bi9517493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tan PK, Wang J, Littler PL, Wong KK, Sweetnam TA, Keefe W, Nash NR, Reding EC, Piu F, Brann MR, Schiffer HH. Monitoring interactions between receptor tyrosine kinases and their downstream effector proteins in living cells using bioluminescence resonance energy transfer. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;72:1440–1446. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.039636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Osherov N, Levitzki A. Epidermal-growth-factor-dependent activation of the src-family kinases. Eur J Biochem. 1994;225:1047–1053. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.1047b.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wuttke A, Sagetorp J, Tengholm A. Distinct plasma-membrane PtdIns(4)P and PtdIns(4,5)P2 dynamics in secretagogue-stimulated beta-cells. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:1492–1502. doi: 10.1242/jcs.060525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Horowitz LF, Hirdes W, Suh BC, Hilgemann DW, Mackie K, Hille B. Phospholipase C in living cells: activation, inhibition, Ca2+ requirement, and regulation of M current. J Gen Physiol. 2005;126:243–262. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200509309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F, et al. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Wal J, Habets R, Varnai P, Balla T, Jalink K. Monitoring agonist-induced phospholipase C activation in live cells by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15337–15344. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hertel F, Switalski A, Mintert-Jancke E, Karavassilidou K, Bender K, Pott L, Kienitz MC. A genetically encoded tool kit for manipulating and monitoring membrane phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in intact cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuo MS, Auriau J, Pierre-Eugene C, Issad T. Development of a human breast-cancer derived cell line stably expressing a bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET)-based phosphatidyl inositol-3 phosphate (PIP3) biosensor. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James SR, Downes CP, Gigg R, Grove SJ, Holmes AB, Alessi DR. Specific binding of the Akt-1 protein kinase to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate without subsequent activation. Biochem J. 1996;315(Pt 3):709–713. doi: 10.1042/bj3150709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Manna D, Albanese A, Park WS, Cho W. Mechanistic basis of differential cellular responses of phosphatidylinositol 3,4-bisphosphate- and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-binding pleckstrin homology domains. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32093–32105. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703517200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fujita A, Cheng J, Tauchi-Sato K, Takenawa T, Fujimoto T. A distinct pool of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate in caveolae revealed by a nanoscale labeling technique. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9256–9261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900216106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cochet C, Filhol O, Payrastre B, Hunter T, Gill GN. Interaction between the epidermal growth factor receptor and phosphoinositide kinases. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:637–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Payrastre B, van Bergen en Henegouwen PM, Breton M, den Hartigh JC, Plantavid M, Verkleij AJ, Boonstra J. Phosphoinositide kinase, diacylglycerol kinase, and phospholipase C activities associated to the cytoskeleton: effect of epidermal growth factor. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:121–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.1.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kauffmann-Zeh A, Klinger R, Endemann G, Waterfield MD, Wetzker R, Hsuan JJ. Regulation of human type II phosphatidylinositol kinase activity by epidermal growth factor-dependent phosphorylation and receptor association. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31243–31251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xu JX, Si M, Zhang HR, Chen XJ, Zhang XD, Wang C, Du XN, Zhang HL. Phosphoinositide kinases play key roles in norepinephrine- and angiotensin II-induced increase in phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate and modulation of cardiac function. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6941–6948. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dickson EJ, Jensen JB, Hille B. Golgi and plasma membrane pools of PI(4)P contribute to plasma membrane PI(4,5)P2 and maintenance of KCNQ2/3 ion channel current. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:E2281–2290. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407133111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Szentpetery Z, Varnai P, Balla T. Acute manipulation of Golgi phosphoinositides to assess their importance in cellular trafficking and signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:8225–8230. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000157107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Levine TP, Munro S. Targeting of Golgi-specific pleckstrin homology domains involves both PtdIns 4-kinase-dependent and -independent components. Curr Biol. 2002;12:695–704. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00779-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Balla A, Tuymetova G, Tsiomenko A, Varnai P, Balla T. A plasma membrane pool of phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate is generated by phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase type-III alpha: studies with the PH domains of the oxysterol binding protein and FAPP1. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1282–1295. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-07-0578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.