Abstract

Objective

To examine associations of television viewing with eating behaviors in a representative sample of US adolescents.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Public and private schools in the United States during the 2009–2010 school year.

Participants

A total of 12 642 students in grades 5 to 10 (mean [SD] age, 13.4[0.09] years; 86.5% participation).

Main Exposures

Television viewing (hours per day) and snacking while watching television (days per week).

Main Outcome Measures

Eating (≥1 instance per day) fruit, vegetables, sweets, and sugary soft drinks; eating at a fast food restaurant (≥1 d/wk); and skipping breakfast (≥1 d/wk).

Results

Television viewing was inversely related to intake of fruit (adjusted odds ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.88–0.96) and vegetables (0.95; 0.91–1.00) and positively related to intake of candy (1.18; 1.14–1.23) and fast food (1.14; 1.09–1.19) and skipping breakfast (1.06; 1.02–1.10) after adjustment for socioeconomic factors, computer use, and physical activity. Television snacking was related to increased intake of fruit (adjusted odds ratio, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.02–1.10), candy (1.20; 1.16–1.24), soda (1.15; 1.11–1.18), and fast food (1.09; 1.06–1.13), independent of television viewing. The relationships of television viewing with fruit and vegetable intake and with skipping breakfast were essentially unchanged after adjustment for television snacking; the relationships with intake of candy, soda, and fast food were moderately attenuated. Age and race/ethnicity modified relationships of television viewing with soda and fast food intake and with skipping breakfast.

Conclusion

Television viewing was associated with a cluster of unhealthy eating behaviors in US adolescents after adjustment for socioeconomic and behavioral covariates.

Dietary intakes of US youth fall short of recommendations for whole fruit, whole grains, legumes, and dark green and orange vegetables and exceed recommendations for fat, sodium, and added sugars,1–3 increasing the risk of obesity and chronic disease throughout the lifespan.4–12 Further understanding of the factors contributing to youth eating behaviors is necessary to improve dietary intakes and associated health outcomes.

Television viewing (TVV) in youth has been associated with unhealthy dietary intake and food preferences that may track into early adulthood.13 Positive associations have been found with intakes of fast food,14–18 soda,16,17,19–27 refined grains,28 and energy-dense foods,17,20,25,27,29,30 as well as with energy intake.6,16,25 In addition, TVV has been inversely associated with fruit and vegetable intake.16,19–21,25,27,31

A primary explanation for these findings is the impact of exposure to food advertisements, which highlight primarily energy-dense, nutrient-poor products and influence food preferences and intake in a variety of youth populations.32–34 Eating while watching TV is another hypothesized mechanism for observed relationships between TVV and diet,17,29,35,36 although, to our knowledge, this has not been tested in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. In addition, despite evidence of sociodemographic differences in TVV37,38 and eating behaviors,39,40 few studies have investigated potential effect modification by these variables.6,41,42

The objective of this study was to examine associations between TVV and eating behaviors in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. We also sought to investigate differences across age, sex, and race/ ethnicity and to ascertain the role of snacking while watching TV. Specific eating behaviors examined included intake of fruit, vegetables, sugar-sweetened soda, and sweets; eating at a fast food restaurant; and skipping breakfast.

METHODS

STUDY DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study is a survey of adolescents conducted every 4 years in the United States beginning in 1995 to monitor and understand youth health behaviors, their social context, health, and well-being. Data collection and procedural details have been published elsewhere.43 We used data from the 2009–2010 US survey, which included a nationally representative sample of 12 642 students in grades 5 through 10 (mean [SD] age, 13.4 [0.09] years). The sample was selected using a 3-stage stratified clustered sampling procedure, with school districts as the primary sampling unit. The survey was administered in classrooms by independent research staff. Black/African American and Hispanic students were oversampled to produce reliable estimates for these groups. There was 86.5% participation among 14 620 eligible students. Questions were validated in several countries in target age groups. Youth assent and active or passive parental consent were obtained as required by participating school districts. The institutional review board of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development approved study procedures.

VARIABLES

Television viewing time was assessed by asking (separately for weekdays and weekends), “About how many hours a day do you usually watch television (including videos and DVDs) in your free time?”. Response categories included “none at all,” “about half an hour a day,” “about 1 hour a day,” “about 2 hours a day,” and so on to “about 7 or more hours a day.” Similar questions and identical responses were used to assess computer use. The survey asked (separately for weekdays and weekends), “About how many hours a day do you usually play games on a computer or games console (PlayStation, Xbox, Game-Cube, etc) in your free time?” and “About how many hours a day do you usually use a computer for chatting online, Internet, e-mailing, homework, etc, in your free time?”. Weekday and weekend responses were combined to obtain average daily hours of TVV and computer use. The combined variable for computer use for games and other purposes was used in final analyses because of the lack of an independent contribution of separate computer use variables in regression models.

Eating behaviors were assessed by asking, “How many times a week do you usually eat or drink … ” followed by “fruits,” “vegetables,” “sweets (candy or chocolate),” and “Coke or other soft drinks that contain sugar” (soda), with response options for “never,” “less than once a week,” “once a week,” “2 to 4 days a week,” “5 to 6 days a week,” “once a day, every day,” and “every day, more than once.” Skipping breakfast was assessed by asking (separately for weekdays and weekends), “How often do you usually have breakfast (more than a glass of milk or fruit juice)?”. Weekday response options included “I never have breakfast during weekdays,” “1 day,” “2 days,” “3 days,” “4 days,” or “5 days.” Weekend response options included “I never have breakfast during the weekend,” “I usually have breakfast on only 1 day of the weekend (Saturday OR Sunday),” and “I usually have breakfast on both weekend days (Saturday AND Sunday).” Weekday and weekend responses were combined to create a single variable indicating whether breakfast was skipped at least 1 day per week. Eating at a fast food restaurant was assessed by asking, “How often do you eat in a fast food restaurant (for example, McDonald’s, KFC, Pizza Hut, Taco Bell)?,” with response options for “never,” “rarely (less than once a month),” “once a month,” “2 to 3 times a month,” “once a week,” “2 to 4 days a week,” and “5 or more days a week.”

Snacking during TVV and computer use were assessed in participants in grades 7 through 10 by asking, “How often do you eat a snack while you … ” followed by “watch TV (including videos and DVDs)” and “work or play on a computer or games console,” with response options for “never,” “less than once a week,” “1 to 2 days a week,” “3 to 4 days a week,” “5 to 6 days a week,” and “every day.” Leisure-time vigorous physical activity was assessed by asking, “Outside school hours: how many hours a week do you usually exercise in your free time so much that you get out of breath or sweat?,” with responses for “none,” “about half an hour,” “about 1 hour,” “about 2 to 3 hours,” “about 4 to 6 hours,” and “7 hours or more.”

Students reported age, sex, race (“What do you consider your race to be?,” with response options for “black or African American” [hereafter referred to as black], “white,” “Asian,” “American Indian or Alaska native,” “Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander,” and “other” with a blank space provided), and ethnicity (“What do you consider your ethnicity to be?,” with response options for “Hispanic or Latino” and “not Hispanic or Latino”). We combined responses to create a 4-category race/ ethnicity variable: non-Hispanic white (white), non-Hispanic black/African American (black/African American), Hispanic, and other. Socioeconomic status was assessed by the Family Affluence Scale, a measure with demonstrated content and external validity44 that was developed for the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Study on the basis of responses to questions about computer and automobile ownership, whether the student shares a bedroom, and frequency of family vacations.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Descriptive statistics were calculated and compared by sex, age, and race/ethnicity using regression analysis for continuous outcomes and the Pearson/Wald test for binary outcomes. Multiple logistic regressions assessed relationships between TVV (hours per day) and daily intake of fruit, vegetables, sweets, and soda, as well as skipping breakfast at least 1 day per week and eating at a fast food restaurant at least 1 day per week. We examined interactions of TVV with age, sex, and race/ethnicity with multiplicative interaction terms and stratified analyses where warranted. Relationships between TVV and dietary behaviors after controlling for frequency of TV and computer snacking were explored in grades 7 through 10; we further examined the interaction of TVV and TV snacking in this subpopulation. All independent variables were continuous except sex and race/ ethnicity. Analyses accounted for the complex survey sampling design using STATA, version 11 (StataCorp).

RESULTS

There were significant sociodemographic differences in most eating behaviors except fast food, which was not different by sex but was more frequent for older (aged ≥13 years) vs younger (<13 years) participants and for racial/ethnic groups compared with white youth (P<.001) (Table 1 and Table 2). Odds of daily intake of fruit and vegetables were higher for younger than older participants, for girls compared with boys, and for white and other groups compared with black and Hispanic youth. Odds of daily intake of sweets were highest for older vs younger youth, for girls vs boys, and for black youth compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Odds of drinking soda at least daily were highest for older vs younger youth, for boys vs girls, and for black and Hispanic youth compared with other racial/ethnic groups. Skipping breakfast was more common for older than younger participants, for girls vs boys, and for black, Hispanic, and “other” youth vs white participants.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Sex and Age

| Characteristic | Total (N=12 642) | Sex

|

Age, y

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n=6502) | Female (n=6136) | P Valuea | <13 (n=5152) | ≥13 (n=7397) | P Valuea | ||||

| Family Affluence Scale score, mean (SE) | 5.4 (0.06) | 5.3 (0.06) | 5.4 (0.07) | .05 | 5.4 (0.07) | 5.3 (0.06) | .25 | ||

| Food intake, No. (%), times per day | |||||||||

| Fruit | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 5297 (44.6) | 2562 (41.8) | 2734 (47.5) |

|

<.001 | 2412 (51.4) | 2832 (39.6) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 6724 (54.4) | 3577 (58.2) | 3145 (52.5) | 2392 (48.6) | 4299 (60.4) | ||||

| Vegetables | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 4382 (38.7) | 2067 (35.2) | 2314 (42.3) |

|

<.001 | 1886 (41.7) | 2450 (36.2) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 7459 (61.3) | 3955 (64.8) | 3502 (57.7) | 2820 (58.3) | 4601 (63.8) | ||||

| Sweets | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 2941 (24.7) | 1352 (22.4) | 1588 (27.1) |

|

.001 | 1084 (22.5) | 1841 (26.3) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 8863 (75.3) | 4656 (77.6) | 4205 (72.9) | 3619 (77.5) | 5197 (73.7) | ||||

| Soda | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 3637 (30.1) | 1881 (30.9) | 1754 (29.3) |

|

.01 | 1277 (26.2) | 2347 (33.2) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 8312 (69.9) | 4198 (69.1) | 4113 (70.7) | 3504 (73.8) | 4738 (66.8) | ||||

| Skipping breakfast, No. (%), d/wk | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 799 (54.8) | 3239 (51.8) | 3558 (58.0) |

|

<.001 | 2332 (45.9) | 4443 (61.9) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 5236 (45.2) | 2879 (48.2) | 2355 (42.0) | 2529 (54.1) | 2644 (38.1) | ||||

| Fast food, No. (%), d/wk | |||||||||

| ≥1 | 4256 (34.1) | 2215 (35.0) | 2038 (33.2) |

|

.17 | 1574 (31.7) | 2666 (36.3) |

|

.02 |

| <1 | 8218 (65.9) | 4184 (65.0) | 4034 (66.8) | 3465 (68.3) | 4682 (63.7) | ||||

| Television viewing, mean (SE), h/d | 2.4 (0.06) | 2.5 (0.06) | 2.4 (0.07) | .005 | 2.5 (0.07) | 2.4 (0.06) | .79 | ||

| Computer use, mean (SE), h/d | 2.8 (0.08) | 3.1 (0.10) | 2.5 (0.08) | <.001 | 2.5 (0.09) | 3.0 (0.09) | <.001 | ||

| TV snacking, mean (SE), d/wkb | 3.3 (0.06) | 3.3 (0.07) | 3.3 (0.08) | .58 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Computer snacking, mean (SE), d/wkb | 2.4 (0.07) | 2.54 (0.08) | 2.24 (0.08) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Physical activity, mean (SE), h/wk | 1.6 (0.03) | 1.8 (0.03) | 1.4 (0.04) | <.001 | 1.6 (0.04) | 1.6 (0.03) | .21 | ||

Abbreviation: NA, not applicable.

By t test or Pearson χ2 test of overall association.

Assessed only in respondents in grades 7 through 10.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Race/Ethnicity

| Characteristic | White (n=5334) | Black (n=2302) | Hispanic (n=3407) | Other (n=1458) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Affluence Scale score, mean (SE) | 5.7 (0.06) | 5.1 (0.07) | 4.9 (0.08) | 5.3 (0.09) | <.001 | |

| Food intake, No. (%), times per day | ||||||

| Fruit | ||||||

| ≥1 | 2339 (46.0) | 924 (41.3) | 1337 (41.9) | 634 (46.9) |

|

.02 |

| <1 | 2821 (54.0) | 1222 (58.7) | 1868 (58.1) | 750 (53.1) | ||

| Vegetables | ||||||

| ≥1 | 2072 (41.5) | 785 (37.0) | 930 (30.5) | 542 (41.1) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 3032 (58.5) | 1327 (63.0) | 822 (69.5) | 822 (58.9) | ||

| Sweets | ||||||

| ≥1 | 1068 (21.8) | 754 (34.9) | 759 (23.7) | 333 (24.7) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 4008 (78.2) | 1338 (65.1) | 2394 (76.3) | 1034 (75.3) | ||

| Soda | ||||||

| ≥1 | 1294 (26.5) | 879 (40.7) | 1102 (34.5) | 337 (25.1) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 3849 (73.5) | 1247 (59.3) | 2090 (65.6) | 1033 (74.9) | ||

| Skipping breakfast, No. (%), d/wk | ||||||

| ≥1 | 2634 (50.4) | 1326 (60.9) | 1967 (61.0) | 816 (56.1) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 2549 (49.6) | 822 (39.1) | 1230 (39.0) | 569 (43.9) | ||

| Fast food, No. (%), d/wk | ||||||

| ≥1 | 1528 (29.1) | 990 (44.8) | 1253 (38.6) | 446 (33.7) |

|

<.001 |

| <1 | 3756 (70.9) | 1276 (55.2) | 2101 (61.4) | 992 (66.3) | ||

| Television viewing, mean (SE), h/d | 2.0 (0.05) | 3.4 (0.07) | 2.7 (0.06) | 2.4 (0.08) | <.001 | |

| Computer use, mean (SE), h/d | 2.4 (0.08) | 3.6 (0.11) | 3.1 (0.09) | 3.1 (0.13) | <.001 | |

| Television snacking, mean (SE), d/wk | 3.0 (0.06) | 4.3 (0.08) | 3.4 (0.10) | 3.0 (0.10) | .02 | |

| Computer snacking, mean (SE), d/wk | 2.0 (0.06) | 3.2 (0.10) | 2.6 (0.12) | 2.4 (0.14) | <.001 | |

| Physical activity, mean (SE), h/wk | 1.8 (0.03) | 1.4 (0.04) | 1.4 (0.03) | 1.6 (0.06) | <.001 | |

By t test or Pearson χ2 test of overall association.

Television viewing did not differ by age group but was lower for girls than boys (approximately0.1 h/d) and higher for black participants vs other racial/ethnic groups (approximately1.0–1.4 h/d). Computer use was lower for younger vs older participants, for girls vs boys, and for white vs other racial/ethnic groups. Television snacking did not differ by sex or age but was more frequent for black youth vs other racial/ethnic groups. Computer snacking was less frequent for girls than boys (approximately0.25 d/wk) and more frequent for black participants vs other ethnic/ racial groups (approximately0.8–1.2 d/wk). Leisure-time vigorous physical activity was lower for girls vs boys (approximately0.4 h/wk) and higher for white participants vs other racial/ethnic groups (approximately0.2–0.4 h/wk).

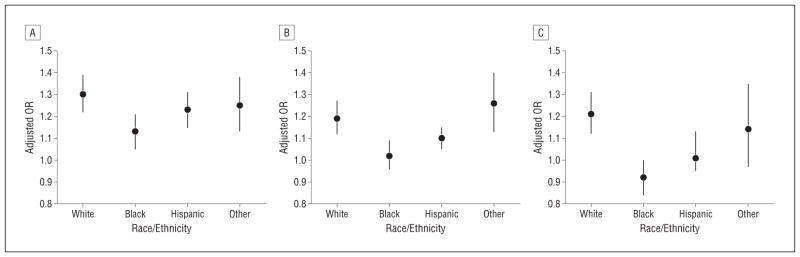

Television viewing time was inversely related to fruit and vegetable intake and positively related to sweets and soda intake, fast food intake, and skipping breakfast in models adjusted for computer use, physical activity, age, sex, family affluence, and race/ethnicity (Table 3). Relationships differed by age and race/ethnicity (Figure); we did not find differences by sex. Relationships with soda (Figure, A) and fast food (Figure, B) intake and with skipping breakfast (Figure, C) differed according to race/ ethnicity, whereas relationships with skipping breakfast differed as well by age (Figure, C). There was a positive relationship of TVV with soda intake for all race/ ethnicities, although the relationship was weaker for black (adjusted odds ratio,1.13; 95% CI,1.05–1.21) compared with white (1.30; 1.22–1.39) youth (P=.001). Television viewing time was positively related to fast food in white youth (adjusted odds ratio,1.19; 95% CI,1.12–1.27) and in Hispanic youth (1.10; 1.05–1.15); the relationship with fast food was not significant for black youth. Skipping breakfast was not related to TVV in youth aged 13 or older (1.03; 0.99–1.07). In participants younger than 13, there was a positive relationship between TVV and skipping breakfast in white youth (adjusted odds ratio, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.12–1.31) but an inverse relationship in black youth and no significant relationship in Hispanic youth (1.01; 0.97–1.35) (Figure, C). Estimates were similar between white and other participants.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios From Multiple Logistic Regressions Predicting Eating Behaviorsa

| Characteristic | Eating Behavior, Odds Ratio (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit (n=9196) | Vegetables (n=9069) | Candy (n=9047) | Soda (n=9155) | Fast Food (n=9513) | Skipping Breakfast (n=9322) | |

| Television viewing, h/d | 0.92 (0.88–0.96) | 0.95 (0.91–1.00) | 1.18 (1.14–1.23) | 1.24 (1.20–1.29) | 1.14 (1.09–1.19) | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) |

| Computer/games, h/d | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) | 0.97 (0.95–1.00) | 1.12 (1.09–1.15) | 1.13 (1.10–1.16) | 1.06 (1.04–1.09) | 1.04 (1.01–1.07) |

| Physical activity, h/wk | 1.27 (1.22–1.33) | 1.25 (1.19–1.31) | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 0.93 (0.88–0.99) | 1.00 (0.94–1.05) | 0.95 (0.90–0.99) |

| Age, y | 0.86 (0.82–0.89) | 0.93 (0.90–0.97) | 1.07 (1.02–1.12) | 1.09 (1.04–1.15) | 1.06 (1.01–1.12) | 1.24 (1.19–1.30 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.29 (1.14–1.47) | 1.43 (1.27–1.61) | 1.32 (1.15–1.51) | 0.96 (0.84–1.08) | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) | 1.42 (1.29–1.57) |

| Family Affluence Scale score | 1.13 (1.09–1.18) | 1.10 (1.05–1.15) | 1.00 (0.94–1.06) | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | 1.08 (1.04–1.13) | 0.87 (0.84–0.91) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Black | 1.10 (0.93–1.29) | 1.08 (0.91–1.28) | 1.37 (1.11–1.69) | 1.16 (0.94–1.43) | 1.62 (1.28–2.06) | 1.13 (0.94–1.37) |

| Hispanic | 1.05 (0.87–1.28) | 0.78 (0.65–0.94) | 0.88 (0.73–1.05) | 1.01 (0.80–1.27) | 1.43 (1.18–1.75) | 1.26 (1.07–1.48) |

| Other | 1.09 (0.87–1.36) | 1.00 (0.79–1.27) | 0.98 (0.79–1.20) | 0.73 (0.61–0.88) | 1.16 (0.91–1.46) | 1.22 (1.03–1.43) |

Separate models predicting at least daily intake of fruit, vegetables, candy, and soda and at least weekly eating at a fast food restaurant and skipping breakfast. Models are adjusted for all characteristics.

Figure.

Associations of television viewing and eating behaviors by race/ethnicity and age. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) of (A) drinking soda (≥1 instance per day) among all youth (A), eating fast food (≥1 d/wk) among all youth (B), and skipping breakfast at least 1 day per week among youth younger than 13 (C) associated with television viewing time (hours per day) by race/ethnicity. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Associations with soda intake were significantly different for black compared with white youth (P=.001). Associations with fast food were significantly different for black (P=.001), Hispanic (P<.001), and “other” (P<.001) youth compared with white youth. Associations with skipping breakfast were significantly different for black (P<.001) and Hispanic (P=.006) youth compared with white youth. Odds ratios were adjusted for computer use, physical activity, age, sex, and family affluence.

Television viewing time and TV snacking were independently related to eating behaviors in participants in grades 7 through 10 in adjusted models (Table 4). Television snacking was positively related to daily intake of fruit, candy, and soda and to fast food but was unrelated to vegetable intake and skipping breakfast. Independent relationships of TVV with intake of candy and soda and with fast food were moderately attenuated but remained statistically significant after adjustment for TV and computer snacking (relationships with eating behaviors unadjusted for TV and computer snacking were similar in participants in grades 7 through 10 as in the overall sample, so separate estimates are not reported). Independent relationships of TVV with fruit and vegetable intake and skipping breakfast were essentially unchanged after adjustment for TV and computer snacking. We found no interactions between TVV and TV snacking for any eating behavior (results not shown).

Table 4.

Logistic Regressions Predicting Eating Behaviors of Participants in Grades 7 Through 10a

| Characteristic | Eating Behavior, Odds Ratio (95% CI)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fruit | Vegetable | Candy | Soda | Fast Food | Skipping Breakfast | |

| Television viewing, h/d | 0.91 (0.87–0.95) | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | 1.09 (1.04–1.14) | 1.05 (1.01–1.10) |

| Computer/games, h/d | 0.96 (0.93–0.99) | 0.97 (0.94–1.00) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 1.01 (0.98–1.04) | 1.04 (1.00–1.07) |

| Physical activity, h/wk | 1.24 (1.19–1.30) | 1.23 (1.17–1.29) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.97 (0.91–1.03) |

| Television snacking, d/wk | 1.06 (1.02–1.10) | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) | 1.20 (1.16–1.24) | 1.15 (1.11–1.18) | 1.09 (1.06–1.13) | 0.99 (0.96–1.02) |

| Computer snacking, d/wk | 1.02 (0.99–106) | 1.02 (0.98–1.05) | 1.12 (1.08–1.16) | 1.13 (1.09–1.17) | 1.09 (1.06–1.12) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) |

| Age, y | 0.87 (0.81–0.93) | 0.94 (0.88–1.01) | 1.07 (0.99–1.14) | 1.09 (1.03–1.16) | 1.10 (1.02–1.18) | 1.18 (1.12–1.25) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Female | 1.21 (1.02–1.43) | 1.31 (1.14–1.49) | 1.26 (1.06–1.49) | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) | 0.94 (0.78–1.13) | 1.61 (1.44–1.80) |

| Family Affluence Scale score | 1.13 (1.07–1.19) | 1.08 (1.03–1.13) | 0.99 (0.93–1.06) | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | 1.13 (1.08–1.19) | 0.90 (0.85–0.94) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] | 1.00 [Reference] |

| Black | 1.19 (0.99–1.42) | 1.06 (0.87–1.30) | 1.48 (1.21–1.80) | 1.20 (0.96–1.50) | 1.63 (1.26–2.10) | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) |

| Hispanic | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | 0.75 (0.61–0.91) | 0.96 (0.78–1.20) | 1.10 (0.86–1.41) | 1.65 (1.28–2.11) | 1.27 (1.08–1.51) |

| Other | 1.14 (0.85–1.54) | 0.93 (0.69–1.25) | 0.90 (0.69–1.17) | 0.68 (0.53–0.85) | 1.28 (0.96–1.71) | 1.38 (1.12–1.71) |

Separate models predicting at least daily intake of fruit, vegetables, candy, and soda and at least weekly eating at a fast food restaurant and skipping breakfast. Models are estimated for participants in grades 7 through 10 only and are adjusted for all characteristics.

COMMENT

This study provides estimates of associations of TVV and eating behaviors in a diverse representative sample of US adolescents. Television viewing time was associated with lower odds of consuming fruit or vegetables daily and higher odds of consuming candy and sugar-sweetened soda daily, skipping breakfast at least 1 day per week, and eating at a fast food restaurant at least 1 day per week in models adjusted for computer use, physical activity, age, sex, race/ethnicity, and family affluence. The relationship of TVV with this unhealthy combination of eating behaviors may contribute to the documented relationship of TVV with cardiometabolic risk factors.4,45,46

Many of our prevalence estimates vary somewhat from previously reported findings, likely because of differences in assessment methods. Our estimates of TVV (2.4 h/d) and computer use (2.8 h/d) are similar to and more than an hour greater, respectively, than previous estimates.38,47 Reported vigorous physical activity in our sample is substantially lower than previous estimates of moderate to vigorous physical activity.38,47–49 Report of skipping breakfast in our sample (54.8%≥1 d/wk) was higher than a recent National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey estimate (20%).50 In addition, our estimate of frequency of eating at a fast food restaurant is lower than findings of a study of California adolescents, in which 46% reported eating fast food at least 2 times per week51 and recent estimates from a nationally representative sample reporting a mean 2 to 3 fast food meals per week,52,53 although multiple fast food meals may be consumed on a single day.

Relationships of TVV with soda intake, fast food, and breakfast behaviors differed according to race/ethnicity. The relationship with soda intake was attenuated for black participants compared with white participants, although relationships were positive for all groups. In addition, the relationship of TVV with fast food was not significant for black youth, whereas this relationship was positive in other racial/ethnic groups. We found differential relationships of TVV with skipping breakfast by both race/ethnicity and age. Among respondents younger than 13, TVV was positively related to skipping breakfast in white adolescents but inversely related to skipping breakfast in black adolescents. There was no relationship in Hispanic adolescents or in those aged 13 or older of any race/ethnicity. These findings are potentially explained by a relationship of TVV with sleep duration and morning sleepiness in youth that may vary with respect to factors associated with child age and race/ ethnicity.54 Our results indicated that relationships of TVV and intake of fruit and vegetables did not differ according to race/ethnicity, contrary to findings of a previous study using data from the 1999 national Youth Risk Behavior Survey.42 In addition, relationships were not different according to sex, as has been suggested in previous research.6,41 Likely because of the heterogeneous make-up of the “other” subgroup, we found few differences from white participants, apart from overall lower odds of drinking soda daily and higher odds of skipping breakfast. Differential associations by race/ethnicity suggest the importance of social, cultural, or other contextual factors42,55 that may contribute to variability in associations of TVV with eating behaviors. However, despite differential associations by sociodemographic factors, our findings of associations of TVV and eating behaviors across all races/ethnicities were nearly universally inconsistent with healthful eating patterns.

Our results demonstrated relationships of TV snacking with several eating behaviors after adjustment for TVV, computer use, physical activity, computer snacking, and sociodemographic characteristics. Although a measure of overall snacking frequency was not available, our finding of independent relationships of eating behaviors with both TV and computer snacking suggest that these measures represent specific modes of snacking rather than serving as proxies for overall snacking. Results indicating positive relationships of TV snacking with candy and soda intake and with eating at a fast food restaurant support previous research documenting adverse associations of eating while watching TV and nutritional quality of foods consumed.20,21,56,57 Previous experimental research has also demonstrated a positive association of eating while watching TV on food quantity consumed in undergraduates29 and children.36 This evidence suggests TV snacking may influence the amount and quality of food consumed.

Relationships of TVV with eating behaviors were essentially unchanged after adjustment for TV snacking, and we found no evidence of effect modification between TVV and TV snacking, suggesting that TV snacking does not fully account for relationships between TVV and eating behaviors. This evidence, together with our finding that TVV was strongly and positively related to the intake of highly advertised foods and either weakly related or unrelated to rarely advertised foods, supports a hypothesized influence of TV food advertisement exposure on dietary intake consistent with experimental research.58,59 Although data indicate a recent decrease in adolescents’ exposure to candy and soda advertisements, exposure to fast food restaurant advertisements has increased.60 In addition, the nutritional quality of advertised foods is poor,33,34,61 and fruit and vegetable advertisements are essentially nonexistent.34,60,62–64 Alternatively, these findings may reflect a clustering of unhealthy behaviors related to unobserved factors, such as an increased tendency to snack during essentially unoccupied time or preferential selection of foods conducive to snacking. Associations of TVV and TV snacking with eating behaviors were evident after adjustment for several covariates intended to reduce confounding by characteristics such as general preference for health and related behaviors, although the potential for residual bias persists in observational research.

Interpretation of these findings must take into account the relative strengths and weaknesses of this study. Our findings rely on a brief assessment of dietary intake rather than a more detailed method (eg, food frequency questionnaire or dietary recall), which may have hindered our ability to detect significant relationships. An important limitation is the cross-sectional study design, which does not allow for determination of causality because of the inability to establish temporality and the potential for confounding by unobserved factors. Thus, we cannot rule out, for example, the possibility that youth with poor dietary behaviors, including a greater tendency toward snacking, are more likely to watch TV. However, previous interventions to reduce TVV in children and adolescents have shown evidence of a beneficial influence on eating while watching TV65,66 as well as on total energy intake41,67 and fruit and vegetable intake,41,68 supporting a causal role of TVV on dietary intake. In addition, the internal validity of our findings is strengthened by our adjustment for several behavioral and socioeconomic confounders. Our study is further strengthened by the high participation rate and the use of a representative sample of US adolescents, including over-sampling of black and Hispanic youth to enable subgroup analysis.

These findings show that TVV is related to a cluster of unhealthy eating behaviors in US adolescents after controlling for TV snacking, computer snacking, socioeconomic variables, computer use, and physical activity. Relationships of TVV with eating behaviors were modified by age and race/ethnicity, suggesting the importance of cultural or social factors. Future research should elucidate the independent contributions of TVV, food advertising, and TV snacking on dietary intake in this population. If these relationships are causal, efforts to reduce TVV or to modify the nutritional content of advertised foods may lead to substantial improvements in adolescents’ dietary intake.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was funded by grant HHSN2672008000009C from the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Health Resources and Services Administration.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: None reported.

Author Affiliations: Dr Lipsky had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Lipsky and Iannotti. Acquisition of data: Iannotti. Analysis and interpretation of data: Lipsky and Iannotti. Drafting of the manuscript: Lipsky and Iannotti. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Lipsky and Iannotti. Obtained funding: Iannotti. Administrative, technical, and material support: Iannotti.

References

- 1.Cohen DA, Sturm R, Scott M, Farley TA, Bluthenthal R. Not enough fruit and vegetables or too many cookies, candies, salty snacks, and soft drinks? Public Health Rep. 2010;125(1):88–95. doi: 10.1177/003335491012500112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fungwe T, Guenther PM, Juan W, Hiza H, Lino M. The quality of children’s diets in 2003–04 as measured by the Healthy Eating Index—2005. Washington, DC: US Dept of Agriculture Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion; 2009. Report 43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reedy J, Krebs-Smith SM. Dietary sources of energy, solid fats, and added sugars among children and adolescents in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(10):1477–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aadahl M, Kjaer M, Jørgensen T. Influence of time spent on TV viewing and vigorous intensity physical activity on cardiovascular biomarkers: the Inter 99 study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2007;14(5):660–665. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3280c284c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen RE, Crespo CJ, Bartlett SJ, Cheskin LJ, Pratt M. Relationship of physical activity and television watching with body weight and level of fatness among children: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 1998;279(12):938–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.12.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crespo CJ, Smit E, Troiano RP, Bartlett SJ, Macera CA, Andersen RE. Television watching, energy intake, and obesity in US children: results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2001;155(3):360–365. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.155.3.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gortmaker SL, Must A, Sobol AM, Peterson K, Colditz GA, Dietz WH. Television viewing as a cause of increasing obesity among children in the United States, 1986–1990. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1996;150(4):356–362. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1996.02170290022003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Healy GN, Dunstan DW, Salmon J, Shaw JE, Zimmet PZ, Owen N. Television time and continuous metabolic risk in physically active adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):639–645. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181607421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu FB. Sedentary lifestyle and risk of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Lipids. 2003;38(2):103–108. doi: 10.1007/s11745-003-1038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakes RW, Day NE, Khaw KT, et al. Television viewing and low participation in vigorous recreation are independently associated with obesity and markers of cardiovascular disease risk: EPIC-Norfolk population-based study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2003;57(9):1089–1096. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martinez-Gomez D, Rey-López JP, Chillón P, et al. AVENA Study Group. Excessive TV viewing and cardiovascular disease risk factors in adolescents: the AVENA cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Viner RM, Cole TJ. Television viewing in early childhood predicts adult body mass index. J Pediatr. 2005;147(4):429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris JL, Bargh JA. Television viewing and unhealthy diet: implications for children and media interventions. Health Commun. 2009;24(7):660–673. doi: 10.1080/10410230903242267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.French SA, Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D, Fulkerson JA, Hannan P. Fast food restaurant use among adolescents: associations with nutrient intake, food choices and behavioral and psychosocial variables. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001;25(12):1823–1833. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer DR, Story MT, Wall MM, Harnack LJ, Eisenberg ME. Fast food intake: longitudinal trends during the transition to young adulthood and correlates of intake. J Adolesc Health. 2008;43(1):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller SA, Taveras EM, Rifas-Shiman SL, Gillman MW. Association between television viewing and poor diet quality in young children. Int J Pediatr Obes. 2008;3(3):168–176. doi: 10.1080/17477160801915935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pearson N, Ball K, Crawford D. Mediators of longitudinal associations between television viewing and eating behaviours in adolescents. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8:23. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-8-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scully M, Dixon H, Wakefield M. Association between commercial television exposure and fast-food consumption among adults. Public Health Nutr. 2009;12(1):105–110. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barr-Anderson DJ, van den Berg P, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Characteristics associated with older adolescents who have a television in their bedrooms. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):718–724. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coon KA, Goldberg J, Rogers BL, Tucker KL. Relationships between use of television during meals and children’s food consumption patterns. Pediatrics. 2001;107(1):E7. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.1.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feldman S, Eisenberg ME, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M. Associations between watching TV during family meals and dietary intake among adolescents. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2007;39(5):257–263. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2007.04.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kremers SP, van der Horst K, Brug J. Adolescent screen-viewing behaviour is associated with consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages: the role of habit strength and perceived parental norms. Appetite. 2007;48(3):345–350. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Péneau S, Mekhmoukh A, Chapelot D, et al. Influence of environmental factors on food intake and choice of beverage during meals in teenagers: a laboratory study. Br J Nutr. 2009;102(12):1854–1859. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509991280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ranjit N, Evans MH, Byrd-Williams C, Evans AE, Hoelscher DM. Dietary and activity correlates of sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among adolescents [published online September 27, 2010] Pediatrics. 2010;126(4):e754–e761. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Utter J, Neumark-Sztainer D, Jeffery R, Story M. Couch potatoes or french fries: are sedentary behaviors associated with body mass index, physical activity, and dietary behaviors among adolescents? J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(10):1298–1305. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(03)01079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van den Bulck J, Van Mierlo J. Energy intake associated with television viewing in adolescents: a cross sectional study. Appetite. 2004;43(2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vereecken CA, Todd J, Roberts C, Mulvihill C, Maes L. Television viewing behaviour and associations with food habits in different countries. Public Health Nutr. 2006;9(2):244–250. doi: 10.1079/phn2005847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ng C, Young TK, Corey PN. Associations of television viewing, physical activity and dietary behaviours with obesity in aboriginal and nonaboriginal Canadian youth. Public Health Nutr. 2010;13(9):1430–1437. doi: 10.1017/S1368980010000832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blass EM, Anderson DR, Kirkorian HL, Pempek TA, Price I, Koleini MF. On the road to obesity: television viewing increases intake of high-density foods. Physiol Behav. 2006;88(4–5):597–604. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson M, Spence JC, Raine K, Laing L. The association of television viewing with snacking behavior and body weight of young adults. Am J Health Promot. 2008;22(5):329–335. doi: 10.4278/ajhp.22.5.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boynton-Jarrett R, Thomas TN, Peterson KE, Wiecha J, Sobol AM, Gortmaker SL. Impact of television viewing patterns on fruit and vegetable consumption among adolescents. Pediatrics. 2003;112(6 pt 1):1321–1326. doi: 10.1542/peds.112.6.1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9(3):221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Institute of Medicine Food and Nutrition Board. Food Marketing to Children and Youth: Threat or Opportunity? Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kunkel D, McKinley C, Wright P. The impact of industry self-regulation on the nutritional quality of foods advertised on television to children. [Accessed February 8, 2012];Children Now website. http://www.childrennow.org/uploads/documents/adstudy_2009.pdf.

- 35.Hill JO, Wyatt HR, Reed GW, Peters JC. Obesity and the environment: where do we go from here? Science. 2003;299(5608):853–855. doi: 10.1126/science.1079857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Temple JL, Giacomelli AM, Kent KM, Roemmich JN, Epstein LH. Television watching increases motivated responding for food and energy intake in children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85(2):355–361. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.2.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giammattei J, Blix G, Marshak HH, Wollitzer AO, Pettitt DJ. Television watching and soft drink consumption: associations with obesity in 11- to 13-year-old schoolchildren. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(9):882–886. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.9.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roberts DF, Foehr UG, Rideout V. Generation M: media in the lives of 8–18-year-olds. Kaiser Family Foundation website; [Accessed February 8, 2012]. http://www.kff.org/entmedia/loader.cfm?url=/commonspot/security/getfile.cfm&PageID=51809. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorson BA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Taylor CA. Correlates of fruit and vegetable intakes in US children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(3):474–478. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2008.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Patrick H, Nicklas TA. A review of family and social determinants of children’s eating patterns and diet quality. J Am Coll Nutr. 2005;24(2):83–92. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2005.10719448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gortmaker SL, Peterson K, Wiecha J, et al. Reducing obesity via a school-based interdisciplinary intervention among youth: Planet Health. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):409–418. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.4.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lowry R, Wechsler H, Galuska DA, Fulton JE, Kann L. Television viewing and its associations with overweight, sedentary lifestyle, and insufficient consumption of fruits and vegetables among US high school students: differences by race, ethnicity, and gender. J Sch Health. 2002;72(10):413–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb03551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts C, Freeman J, Samdal O, et al. International HBSC Study Group. The Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: methodological developments and current tensions. Int J Public Health. 2009;54(suppl 2):140–150. doi: 10.1007/s00038-009-5405-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Currie C, Molcho M, Boyce W, Holstein B, Torsheim T, Richter M. Researching health inequalities in adolescents: the development of the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) Family Affluence Scale. Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(6):1429–1436. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ford ES, Li C, Zhao G, Pearson WS, Tsai J, Churilla JR. Sedentary behavior, physical activity, and concentrations of insulin among US adults. Metabolism. 2010;59(9):1268–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardy LL, Denney-Wilson E, Thrift AP, Okely AD, Baur LA. Screen time and metabolic risk factors among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(7):643–649. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson SE, Economos CD, Must A. Active play and screen time in US children aged 4 to 11 years in relation to sociodemographic and weight status characteristics: a nationally representative cross-sectional analysis. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:366. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nader PR, Bradley RH, Houts RM, McRitchie SL, O’Brien M. Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity from ages 9 to 15 years. JAMA. 2008;300(3):295–305. doi: 10.1001/jama.300.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nelson MC, Neumark-Stzainer D, Hannan PJ, Sirard JR, Story M. Longitudinal and secular trends in physical activity and sedentary behavior during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2006;118(6):e1627–e1634. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-0926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deshmukh-Taskar PR, Nicklas TA, O’Neil CE, Keast DR, Radcliffe JD, Cho S. The relationship of breakfast skipping and type of breakfast consumption with nutrient intake and weight status in children and adolescents: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):869–878. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Babey SH, Wolstein J, Diamant AL. Food environments near home and school related to consumption of soda and fast food. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011:1–8. PB2011-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gordon-Larsen P, Guilkey DK, Popkin BM. An economic analysis of community-level fast food prices and individual-level fast food intake: a longitudinal study. Health Place. 2011;17(6):1235–1241. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richardson AS, Boone-Heinonen J, Popkin BM, Gordon-Larsen P. Neighborhood fast food restaurants and fast food consumption: a national study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:543. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ortega FB, Chillón P, Ruiz JR, et al. Sleep patterns in Spanish adolescents: associations with TV watching and leisure-time physical activity. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;110(3):563–573. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1536-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Furst T, Connors M, Bisogni CA, Sobal J, Falk LW. Food choice: a conceptual model of the process. Appetite. 1996;26(3):247–265. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubois L, Farmer A, Girard M, Peterson K. Social factors and television use during meals and snacks is associated with higher BMI among pre-school children. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(12):1267–1279. doi: 10.1017/S1368980008002887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matheson DM, Killen JD, Wang Y, Varady A, Robinson TN. Children’s food consumption during television viewing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79(6):1088–1094. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halford JC, Gillespie J, Brown V, Pontin EE, Dovey TM. Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004;42(2):221–225. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2003.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Halford JC, Boyland EJ, Hughes G, Oliveira LP, Dovey TM. Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of 5–7-year-old children. Appetite. 2007;49(1):263–267. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Powell LM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ. Trends in exposure to television food advertisements among children and adolescents in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(9):794–802. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Powell LM, Schermbeck RM, Szczypka G, Chaloupka FJ, Braunschweig CL. Trends in the nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children in the United States: analyses by age, food categories, and companies. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(12):1078–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison K, Marske AL. Nutritional content of foods advertised during the television programs children watch most. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(9):1568–1574. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.048058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palmer EL, Carpenter CF. Food and beverage marketing to children and youth: trends and issues. Media Psychol. 2006;8:165–190. doi: 10.1207/s1532785xmep0802_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Story M, French S. Food advertising and marketing directed at children and adolescents in the US. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2004;1(1):3. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinson TN. Reducing children’s television viewing to prevent obesity: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1999;282(16):1561–1567. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.16.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robinson TN, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, et al. Dance and reducing television viewing to prevent weight gain in African-American girls: the Stanford GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1 suppl 1):S65–S77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Epstein LH, Roemmich JN, Robinson JL, et al. A randomized trial of the effects of reducing television viewing and computer use on body mass index in young children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(3):239–245. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gortmaker SL, Cheung LW, Peterson KE, et al. Impact of a school-based interdisciplinary intervention on diet and physical activity among urban primary school children: eat well and keep moving. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(9):975–983. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]