Abstract

Background

Measuring acetabular anteversion is relevant to routine follow-up of total hip arthroplasties (THAs) and for malfunctioning THAs. Imageless navigation facilitates acetabular component orientation relative to the anterior pelvic plane (APP) or to the APP adjusted for sagittal pelvic tilt (PT). The optimal plain radiographic method for the postoperative assessment of anteversion is not agreed upon.

Questions/Purposes

(1) Do anteversion measurements on plain radiographs correlate more with APP anteversion or PT-adjusted anteversion? (2) Do measurements of anteversion performed on supine anteroposterior (AP) radiographs more accurately reflect intraoperative anteversion values for navigated THA compared to anteversion measured on cross-table lateral (CL) radiographs?

Methods

Seventy patients receiving primary navigated THA were included. APP and PT-adjusted anteversion were recorded; the latter defined the intraoperative target for anteversion. Postoperative anteversion was measured on supine AP pelvis radiographs with computer software and CL radiographs with conventional methods. Intraoperative measurements were used as the reference standards for comparisons.

Results

Mean intraoperative APP anteversion was 20.6° ± 5.6°. Mean intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion was 22.9° ± 4.5°. Mean anteversion was 22.7° ± 4.7° on AP radiographs and 27.2° ± 4.2° on CL radiographs (p < 0.001). Only correlations between PT-adjusted anteversion and radiographic assessments of anteversion were significant. The mean difference between PT-adjusted anteversion and anteversion on AP radiographs was −0.2° ± 4.3°, while the mean difference between the PT-adjusted anteversion and anteversion measured on CL radiographs was 4.3 ± 5.1° (p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Plain film assessment of anteversion was more accurate on supine AP radiographs than on CL radiographs, which overestimated acetabular anteversion.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11420-015-9472-6) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: total hip replacement, computer-assisted surgery, radiographic film, anteversion, diagnostic imaging

Introduction

Measuring acetabular component position after total hip arthroplasty (THA) is commonly performed as part of routine postoperative follow-up and as part of the assessment of the malfunctioning THA. Malposition of the acetabular component after THA has been associated with an increase risk of dislocation, polyethylene wear, early component loosening, and negative clinical effects including pain and decreased range of motion [2, 3, 6, 12, 27, 28]. Assessment of acetabular component position is based on a combination of the inclination and anteversion angles. Pelvic computer tomography (CT) scans have been shown to be the most accurate assessment of component position, but significant drawbacks to their routine clinical use include high cost and radiation exposure [5, 15, 25]. While acetabular inclination is easily assessed on anteroposterior (AP) pelvis radiographs, the optimal plain radiographic method for the postoperative assessment of acetabular component anteversion is not agreed upon. Both AP and cross-table lateral (CL) plain radiographs have been used to assess postoperative component anteversion [1, 8, 10, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21, 26, 28]. However, previous studies have found up to a 5° difference between anteversion measured on the AP pelvis and CL radiographs [1]. Further, CT-based acetabular version has been found to most closely correlate with anteversion measured on AP rather than CL radiographs [13, 18].

Computer-assisted surgery (CAS) has been shown to improve the accuracy and reproducibility of component position compared to manual techniques [7, 9, 11, 20, 22–24]. Many CAS systems for THA reference the anterior pelvic plane (APP), a spatial plane defined by bilateral anterior-superior iliac spines (ASIS) and the pubic tubercle, to determine acetabular component anteversion [29]. This measure of anteversion is reported as APP anteversion. Further, these systems commonly report an adjusted anteversion measurement to account for the angle between the coronal plane and the APP. This angle is the patient’s sagittal pelvic tilt (PT) [29]. There is a linear relationship between changes in PT and functional anteversion: anterior PT reduces functional component anteversion by approximately 0.74° per degree of PT, while posterior PT increases it by the same amount [14]. Intraoperatively, the APP is registered with the patient in the supine position [29]. Thus, PT is assessed in the supine position, and supine PT determines the PT-adjusted anteversion. Both APP anteversion and PT-adjusted anteversion values are provided intraoperatively. To our knowledge, no study has compared postoperative radiographic acetabular component anteversion to intraoperative measurements of anteversion.

The purpose of this study was to determine whether postoperative THA acetabular component anteversion is better assessed on supine AP pelvis radiographs or CL radiographs, when the intraoperative navigated component position is used as the reference standard. We asked the following: (1) Do anteversion measurements on plain radiographs correlate more with APP anteversion or PT-adjusted anteversion? (2) Do measurements of acetabular component anteversion performed on supine AP pelvis radiographs more accurately reflect intraoperative anteversion values for navigated THA compared to anteversion measured on CL hip radiographs? We hypothesized that anteversion measured on postoperative radiographs would best correlate with the intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion measurements, rather than APP anteversion, since both the PT-adjusted anteversion measurement and postoperative radiographs are influenced by the sagittal orientation of the pelvis in the supine position [4, 14, 29]. Further, we hypothesized that anteversion assessed on AP pelvis radiographs would more accurately reflect the intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion than anteversion measured on CL radiographs, since CL radiographs are dependent on accurate patient positioning [1, 15, 19, 21, 26].

Patients and Methods

This retrospective cohort study was performed at an urban orthopedic surgery specialty hospital in the USA. Inclusion criteria included patients receiving primary THA performed by a single experienced lower extremity arthroplasty surgeon (DJM) between February and September of 2012. Patients were excluded if they received staged or simultaneous bilateral THA during the study period. Additional exclusion criteria were missing intraoperative navigation data and missing or poor-quality 6-week postoperative AP or CL radiographs. The quality of an AP radiograph was deemed poor if it was not centered on the symphysis pubis and if the sacrococcygeal joint was not centered over the symphysis pubis. A CL radiograph was classified as poor if the opening of the acetabular component did not appear parallel to the X-ray beam [15]. Of 84 patients receiving 90 THAs during the study period, 6 patients (12 THA) were excluded for bilateral surgery, 1 patient was excluded for missing intraoperative data, 1 patient was excluded for a poor-quality AP radiograph, 3 patients did not have CL radiographs, and 3 patients had neither postoperative AP nor CL radiographs available for review. Therefore, 70 THAs in 70 patients met criteria for review.

Patient age at surgery, gender, body mass index (BMI), primary diagnosis, and laterality were available for all patients (Table 1). Each patient received primary, unilateral THA using the same cementless hemispherical acetabular component (R3 Acetabular System; Smith & Nephew plc, Memphis, TN, USA) and cementless femoral component (Synergy; Smith & Nephew plc, Memphis, TN, USA). Bearing couples included either metal on highly cross-linked polyethylene (XLPE) or Oxinium (Smith & Nephew plc, Memphis, TN, USA) on XLPE. Only neutral XLPE acetabular inserts were implanted. All patients underwent THA with the AchieveCAS imageless navigation system (Smith & Nephew plc, Memphis, TN, USA).

Table 1.

Cohort demographics

| THA | |

|---|---|

| (n = 70) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 58 (12) |

| Female, n (%) | 38 (54) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 28 (6) |

| Right, n (%) | 36 (51) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| OA | 61 (87) |

| CHD | 3 (4) |

| AVN | 3 (4) |

| PTA | 3 (4) |

THA total hip arthroplasty, SD standard deviation, BMI body mass index, OA osteoarthritis, CHD childhood hip disease, AVN avascular necrosis, PTA posttraumatic arthritis

With the patient in the supine position, the ipsilateral hemipelvis was prepped and draped. Two 3.2-mm threaded pins were inserted into the anterolateral iliac crest, to which the AchieveCAS pelvic reference array was attached. With the patient in the supine position, the APP, defined by bilateral ASISs and the ipsilateral pubic tubercle, was registered relative to a plane parallel to the operating room floor. The degree of sagittal PT was reported by the AchieveCAS system and recorded in the operative record. The patient was then placed in the lateral decubitus position, re-prepped, and draped, in order to perform the remainder of the THA through the posterolateral approach. The pins for the pelvic reference array were left in situ and prepped into the field, and a sterile array was attached. Once the acetabulum was exposed, the center of the native acetabulum was registered using a trial cup approximately the size of the native femoral head attached to a cup impactor and AchieveCAS instrument array. The acetabulum was reamed to the appropriate size and depth, as judged by the surgeon, and the final acetabular component was impacted into the goal position using the cup impactor and attached instrument array. The target component orientation was approximately 40° of inclination and 20 to 25° of PT-adjusted anteversion [16]. The final component position, including APP anteversion and PT-adjusted anteversion, was recorded from the AchieveCAS output.

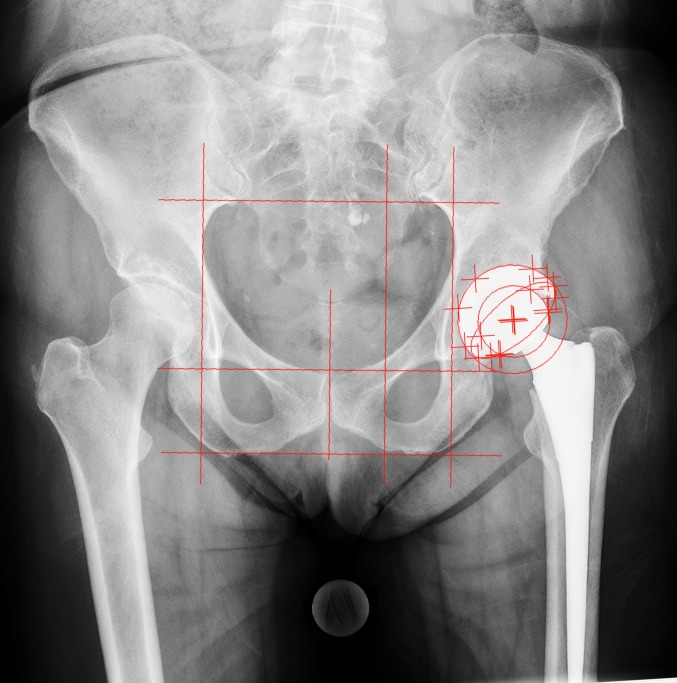

Six weeks after surgery, a supine AP radiograph of the pelvis and a CL radiograph of the operative hip were obtained and were available for review through the hospital’s picture archiving and communication system (PACS). For the AP radiograph, the patient was placed the supine position, with both hips in neutral position and the radiation beam centered on the pubic symphysis. Acetabular anteversion was measured with Ein-Bild-Röntgen-Analyse (EBRA; University of Innsbruck, Austria) software, which is a validated method for assessing acetabular component position [3, 10]. Pelvic parameters were indicated with grid lines, and reference points around the projections of the prosthetic femoral head, hemispherical cup, and its rim were identified (Fig. 1). EBRA calculated radiographic anteversion based on ellipsoid projection of the cup rim onto the plane of the radiograph [10]. For a CL radiograph, the patient was placed in the supine position with the contralateral hip flexed to 90° and the radiation beam directed 45° off the long axis of the body and parallel to the examining table. Acetabular component anteversion was measured as the angle subtended by the long axis of the ellipsoid projection of the component rim onto the plane of the radiograph and a vertical line (Fig. 2) [28]. These measurements were made using digital software tools associated with the PACS (Sectra AB, Linköping, Sweden). All radiographic measurements were performed by a single, experienced observer (PKS) [16] since previous studies have shown excellent intraobserver and interobserver reliability for both EBRA [13, 18, 19, 26] and CL assessments of acetabular anteversion [15, 18, 19]. To avoid bias, the observer was blinded to the intraoperative records.

Fig. 1.

A cross-table lateral radiograph of the patient from Fig. 1 is shown, illustrating the Woo and Morrey [28] method for assessing acetabular anteversion. The angle subtended by a vertical line and a second line parallel to the long axis of the ellipsoid projection of the component rim onto the plane of the radiograph is measured. In this case, acetabular anteversion measured 30°.

Fig. 2.

A supine anteroposterior pelvis radiograph with Ein-Bild-Röntgen-Analyse (EBRA; University of Innsbruck, Austria) grid lines and landmarks is shown. A horizontal baseline was set tangent to the transverse axis of the pelvis in the coronal plane; then, additional vertical grid lines were used to delineate the left and right inner boundaries of the pelvic brim, the medial boundary of the ipsilateral obturator foramen, and the pubic symphysis. Two more horizontal lines were used to delineate the superior and inferior boundaries of the pelvic brim. Multiple reference points were selected along the radiographic projections of the femoral head, the hemispherical contour of the acetabular component, and the acetabular rim. As determined by the EBRA software, acetabular component inclination was 43°, and anteversion was 22°.

Statistical Methods

Patient characteristics were summarized using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for discrete variables. Means and standard deviations were calculated for each anteversion measurement. Pearson’s coefficients were determined to quantify the correlations between radiographic assessments of acetabular anteversion and intraoperative measurements of anteversion. The mean differences and standard deviations between AP and CL anteversion measurements were calculated. Likewise, the mean differences and standard deviations between AP and intraoperative anteversion measurements and the mean differences and standard deviations between CL and intraoperative anteversion measurements were calculated. These latter mean differences and their variances were defined as the accuracy and precision, respectively, for each radiographic method of anteversion measurement, using the intraoperative measurement as the reference standard. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to confirm that the data was normally distributed. Two-tailed paired-sample t tests were used to compare means, and Levene’s test was used to compare the variances between mean differences. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 22 for Macintosh (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). An alpha level of 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

Results

The mean intraoperative APP anteversion was 20.6° ± 5.6° (range, −4.0° to 36.0°). The mean intraoperative PT was −3.5° ± 9.4° (range, −44.0° to 14.0°), and the mean PT-adjusted anteversion was 22.9° ± 4.5° (range, 12.0° to 31.0°). Mean anteversion was 22.7° ± 4.7° (range, 13.2° to 34.9°) as determined by EBRA on AP radiographs, and it was 27.2° ± 4.2° (range 15.0° to 38.3°) on CL radiographs (p < 0.001). The mean difference between anteversion measurements using AP and CL radiographs was 4.5° ± 4.4° (range, −4.1° to 14.0°).

Correlations between APP anteversion and both CL anteversion and AP anteversion were poor (Table 2). Correlations between PT-adjusted anteversion and radiographic assessments of anteversion were significant. The correlation between PT-adjusted anteversion and AP anteversion (r = 0.56, p < 0.001) was greater than between PT-adjusted anteversion and anteversion measured on CL radiographs (r = 0.30, p = 0.012). Pairwise t tests between mean anteversion for intraoperative assessments and postoperative measurements were significantly different, except for between PT-adjusted anteversion and AP anteversion (p = 0.69; Table 3).

Table 2.

Correlations between intraoperative and postoperative assessments of acetabular component anteversion

| N | Correlation | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| APP anteversion vs. CL anteversion | 70 | 0.019 | 0.874 |

| APP anteversion vs. EBRA anteversion | 70 | −0.052 | 0.669 |

| PT-adjusted anteversion vs. CL anteversion | 70 | 0.299 | 0.012 |

| PT-adjusted anteversion vs. EBRA anteversion | 70 | 0.561 | <0.001 |

APP anterior pelvic plane, CL cross-table lateral, EBRA Ein-Bild-Röntgen-Analyse, PT pelvic tilt

Table 3.

Paired-sample mean differences and paired-sample t tests

| Paired differences | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (°) | SD (°) | 95 % Confidence interval | p value* | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | ||||

| APP anteversion less CL anteversion | 6.6 | 6.9 | 5.0 | 8.3 | <0.001 |

| APP anteversion less EBRA anteversion | 2.1 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 3.9 | 0.022 |

| PT-adjusted anteversion less CL anteversion | 4.3 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 5.5 | <0.001 |

| PT-adjusted anteversion less EBRA anteversion | −0.2 | 4.3 | −1.2 | 0.8 | 0.690 |

APP anterior pelvic plane, CL cross-table lateral, PT pelvic tilt, EBRA Ein-Bild-Röntgen-Analyse

*p value for two-tailed paired-sample t test comparing means of each pair of anteversion measurements

The mean difference between intraoperative values of adjusted anteversion and anteversion calculated on the AP radiograph was −0.2° ± 4.3°, while the mean difference between the intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion values and anteversion measured on CL radiographs was 4.3° ± 5.1° (p < 0.001). Thus, anteversion measured on CL radiographs was, on average, 4.3° greater than the intraoperative assessment of PT-adjusted anteversion, and these results imply that anteversion measured on AP radiographs is, on average, 4.1° more accurate (i.e., closer to the true value) than the Woo and Morrey measurement for anteversion, when intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion is used as the reference standard. Levene’s test of variance comparing the mean differences for PT-adjusted anteversion less EBRA anteversion and PT-adjusted anteversion less CL anteversion was not statistically significant (p = 0.144), suggesting that there is equal precision (i.e., spread) between the two postoperative anteversion measurements.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to determine whether postoperative THA acetabular component anteversion is better assessed on supine AP pelvis radiographs or CL radiographs, when the intraoperative navigated component position is used as the reference standard. Both study hypotheses were confirmed. Anteversion measured on postoperative radiographs best correlated with the intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion measurements, rather than APP anteversion, and anteversion assessed on supine AP pelvis radiographs more accurately reflected the intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion than anteversion measured on CL radiographs. Anteversion measured on CL radiographs was, on average, 4.3° greater than PT-adjusted anteversion, whereas anteversion measured on supine AP radiographs with EBRA was, on average, only 0.2° less than PT-adjusted anteversion. The difference between CL anteversion and intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion was significant, whereas the difference between AP anteversion and PT-adjusted anteversion was not. Variances of the mean differences between PT-adjusted anteversion and both EBRA anteversion and CL anteversion were not different, and this may imply a systematic reason for the differences observed between the postoperative anteversion measurements.

This study has several limitations. First, intraoperative navigated anteversion was used as the comparative gold standard rather than anteversion measured on CT. However, acetabular component positioning using imageless navigation has been reported to be accurate to within 2° of CT assessment of acetabular component position [7, 20], and CT scans expose patients to additional ionizing radiation for imaging exams outside of the standard of care for routine THA follow-up. Second, a specific brand of software, EBRA, was used to measure anteversion on AP supine radiographs. It is possible that the results might be different if other software was used. However, most software uses common similar trigonometric functions to calculate acetabular anteversion based upon the radiographic projection of the ellipsoid opening of the component on the plane of the radiograph [10, 12, 13, 18, 19]. Therefore, the results are likely generalizable to other software using similar methods to measure acetabular anteversion. Third, a single observer was used for all radiographic measurements. While this observer was blinded to the intraoperative anteversion measurements, the potential for bias may have reduced further with the addition of multiple observers. Yet, intraobserver and interobserver interclass correlation coefficients for EBRA and CL anteversion measurements have exceeded 0.9 in multiple studies [13, 15, 18, 19, 26]. Fourth, a 4.3° difference between AP and CL anteversion measurements may not be clinically important. One study has attempted to define a minimal clinically important difference in acetabular anteversion based on patient-reported outcomes [6]. This study found that a wide range (15° ± 15°) of anteversion along with 40° ± 15° reduced the risk of postoperative THA dislocation, but superior Oxford Hip Scores were found for patients within a ±5° range of 45° of inclination and 25° of anteversion [6]. Therefore, a 5° difference in anteversion may be clinically significant. However, this result has not been replicated in other studies, and we did not assess patient-reported outcomes in this study. Fifth, EBRA is not standard software for the PACS at the study institution, making it more time consuming than CL anteversion measurements. Therefore, this study’s results may hold clinical relevance only to surgeons with ready access to software capable of measuring anteversion on AP radiographs. However, since other studies have noted the improved reliability of anteversion assessment on AP radiographs compared to lateral radiographs [13, 19, 26], an argument can be made to include tools for AP anteversion assessment in standard PACS workstations. Finally, it should be noted that AP radiographs cannot distinguish between anteversion and retroversion. When acetabular components are placed near neutral version, this limitation may become particularly relevant, and true lateral radiographs may be required to confirm acetabular orientation [26]. The senior surgeon in this study preferred an anteversion target in excess of 20° of PT-adjusted anteversion and used navigation for every THA [16]. Therefore, this limitation of AP radiographs was of less clinical concern than it might be for surgeons with lower anteversion targets and who do not use advanced technologies to assist acetabular component placement. In this study, there were no acetabuli with retroversion on CL radiographs.

The current study found that radiographic measurements of acetabular component anteversion with the patient in the supine position best correlate to intraoperative anteversion measured relative to a coronal plane, the APP, adjusted for a patient’s PT in the supine position. Murray [17] noted that anteversion can be defined as either radiographic, anatomic, or operative. All definitions describe the orientation of the “acetabular axis” that is perpendicular to the opening of the acetabular component and passes through its center. Radiographic anteversion, which was used in this study and for imageless navigation [29], is the angle between the acetabular axis and a coronal plane. Therefore, the coronal plane selected directly influences measured anteversion [14, 17, 29]. In this study, two coronal planes for measuring cup orientation were defined: (1) the APP and (2) a functional coronal plane with the patient in the supine position, which corresponded to the radiographic coronal plane for supine radiographs. Only when there was no sagittal PT where the APP and the radiographic coronal plane parallel. Therefore, in an idealized scenario, PT is 0°. However, in this study’s cohort, mean PT was 3.5° posterior, with a range of 44.0° of posterior PT to 14.0° of anterior PT. When PT is not equal to 0°, there is a linear relationship between radiographic anteversion and PT, with a mean change in anteversion of 0.74° per 1° increase in posterior PT [14]. In this study, since the surgeon targeted PT-adjusted anteversion, the reference planes for intraoperative anteversion and postoperative radiographic anteversion were the same.

The signification correlations between AP and CL anteversion measurements result rely on the constancy of preoperative and postoperative sagittal PT. If PT is not constant or changes as the result of THA, the relationship between the APP, the intraoperative coronal plane, and the radiographic coronal planes will not be constant. While postoperative PT was not measured in this study, both Maratt et al. [14] and Blondel et al. [4] found that PT does not vary significantly in the majority of patients before and after THA. Importantly, PT can vary with contralateral hip flexion during CL radiographs [1], which may explain why CL anteversion did not correlate as strongly with intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion as AP anteversion did.

Several studies have shown that CL anteversion is consistently greater than AP anteversion [1, 19, 26], ranging from 3.4° [19] to 5° [1]. Likewise, we found that anteversion on AP radiographs was, on average, 4.1° more accurate than on CL radiographs, with intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion as the reference standard, but the variances of CL and AP anteversion measurements were equal. These results may imply a systematic reason for the differences observed between the two radiographic methods for measuring anteversion.

Arai et al. [1] found that there was a negative correlation between maximum clinical hip flexion and the difference between anteversions measured on CL and AP radiographs, and they showed that patients with a stiffer contralateral hip showed greater differences between the two version measurements. It is important to realize that clinical “hip flexion,” which is the perceived change in angle between the longitudinal axis of the thigh and the longitudinal axis of the axial skeleton, is a combination of both femoroacetabular flexion and spinopelvic flexion. We speculate that if there is no spinopelvic motion when the contralateral hip is flexed to 90° for a CL radiograph (e.g., in the case of spinopelvic arthrodesis), then CL and AP anteversion measurements should be equivalent, as the supine PT should be equal for both radiographs. However, if the contralateral hip permits limited femoroacetabular motion, then posterior PT should increase to a greater degree for a CL radiograph, and measured CL anteversion should exceed AP anteversion by approximately 0.74° per 1° of additional posterior PT [14]. Thus, in our series, if, on average, there was 4.5° more anteversion on CL radiographs than measured on AP radiographs, we would expect that the pelvis was, on average, tilted approximately 6° more posterior for CL radiographs than for AP exams. Although further study is required to fully delineate the relationships between CL anteversion measurement, femoroacetabular motion, and spinopelvic motion, we hypothesize that the observed difference between AP and CL anteversion measurements should be patient-specific and a function of femoroacetabular and spinopelvic parameters.

It may be possible to control for PT using the ischiolateral method to measure anteversion that Pulos et al. [21] described. This method uses the CL radiograph and measures the angle between a line tangent to the opening of the acetabular opening and a line perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the ischial tuberosity. However, the relationships between the ischial tuberosity, anatomic planes (e.g., the APP), and functional planes (e.g., the supine frontal plane) cannot be determined easily and have not been studied. Therefore, the usefulness of the ischiolateral method is likely confined to comparing serial radiographs of the same patient [26].

In conclusion, anteversion measured on postoperative supine plain radiographs correlated to intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion and not to intraoperative APP anteversion, likely because the PT-adjusted and radiographic reference planes were parallel or nearly parallel. AP anteversion correlated more than CL anteversion to intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion, and it was more accurate than CL anteversion, when compared to intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion. CL radiographs appear to overestimate anteversion compared to AP radiographs and intraoperative PT-adjusted anteversion. We speculate that patient positioning for CL radiographs typically necessitates posterior PT, altering the relationship between the intraoperative and radiographic reference planes and increasing apparent anteversion.

Until tools for measuring anteversion on AP radiographs become commonplace, CL radiographs remain clinically important studies for acetabular version assessment. However, clinicians should be aware that CL radiographs tend to overestimate anteversion. Future studies should explore the relationships between CL anteversion measurement, femoroacetabular motion, and spinopelvic motion and should determine methods to normalize CL anteversion to patient-specific functional reference planes.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

Disclosures

Conflict of Interest

Peter K. Sculco, MD, Alexander S. McLawhorn, MD, MBA, Kaitlin Carroll, BA, and Benjamin A. McArthur, MD, have declared that they have no conflict of interest. David J. Mayman, MD, reports other from OrthoAlign and personal fees from Smith & Nephew and Stryker, outside the work.

Human/Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008 (5).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was waived from all patients for being included in the study.

Required Author Forms

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article.

Footnotes

Level of Evidence: Level III, Diagnostic Study

Work performed at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY.

References

- 1.Arai N, Nakamura S, Matsushita T. Difference between 2 measurement methods of version angles of the acetabular component. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(5):715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrack RL. Dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: implant design and orientation. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11(2):89–99. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biedermann R, Tonin A, Krismer M, Rachbauer F, Eibl G, Stöckl B. Reducing the risk of dislocation after total hip arthroplasty: the effect of orientation of the acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(6):762–769. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B6.14745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blondel B, Parratte S, Tropiano P, Pauly V, Aubaniac JM, Argenson JN. Pelvic tilt measurement before and after total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2009;95(8):568–572. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ghelman B, Kepler CK, Lyman S, Della Valle AG. CT outperforms radiography for determination of acetabular cup version after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467(9):2362–2370. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-0774-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grammatopoulos G, Thomas GE, Pandit H, Beard DJ, Gill HS, Murray DW. The effect of orientation of the acetabular component on outcome following total hip arthroplasty with small diameter hard-on-soft bearings. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(2):164–172. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B2.34294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haaker RG, Tiedjen K, Ottersbach A, Rubenthaler F, Stockheim M, Stiehl JB. Comparison of conventional versus computer-navigated acetabular component insertion. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2005.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hassan DM, Johnston GH, Dust WN, Watson LG, Cassidy D. Radiographic calculation of anteversion in acetabular prostheses. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10(3):369–372. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(05)80187-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalteis T, Handel M, Herold T, Perlick L, Baethis H, Grifka J. Greater accuracy in positioning of the acetabular cup by using an image-free navigation system. Int Orthop. 2005;29(5):272–276. doi: 10.1007/s00264-005-0671-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krismer M, Bauer R, Tschupik J, Mayrhofer P. EBRA: a method to measure migration of acetabular components. J Biomech. 1995;28(10):1225–1236. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(94)00177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar MA, Shetty MS, Kiran KG, Kini AR. Validation of navigation assisted cup placement in total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36(1):17–22. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1268-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewinnek GE, Lewis JL, Tarr R, et al. Dislocations after total hip-replacement arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1978;60:217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lu M, Zhou YX, Du H, Zhang J, Liu J. Reliability and validity of measuring acetabular component orientation by plain anteroposterior radiographs. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(9):2987–2994. doi: 10.1007/s11999-013-3021-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maratt JD, Esposito CI, McLawhorn AS, Jerabek SA, Padgett DE, Mayman DJ. Pelvic tilt in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: when does it matter? J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(3):387–391. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2014.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McArthur B, Cross M, Geatrakas C, Mayman D, Ghelman B. Measuring acetabular component version after THA: CT or plain radiograph? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(10):2810–2818. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2292-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLawhorn AS, Sculco PK, Weeks KD, Nam D, Mayman DJ. Targeting a New Safe Zone: A Step in the Development of Patient-Specific Component Positioning for Total Hip Arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44(6):270–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murray DW. The definition and measurement of acetabular orientation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75:228–232. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B2.8444942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nho JH, Lee YK, Kim HJ, Ha YC, Suh YS, Koo KH. Reliability and validity of measuring version of the acetabular component. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):32–36. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nishino H, Nakamura S, Arai N, Matsushita T. Accuracy and precision of version angle measurements of the acetabular component after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(9):1644–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nogler M, Kessler O, Prassl A, Donnelly B, Streicher R, Sledge JB, et al. Reduced variability of acetabular cup positioning with use of an imageless navigation system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;426(426):159–163. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000141902.30946.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pulos N, Tiberi JV, 3rd, Schmalzried TP. Measuring acetabular component position on lateral radiographs: ischio-lateral method. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(Suppl 1):S84–S89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ryan JA, Jamali AA, Bargar WL. Accuracy of computer navigation for acetabular component placement in THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(1):169–177. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sendtner E, Schuster T, Worner M, Kalteis T, Grifka J, Renkawitz T. Accuracy of acetabular cup placement in computer-assisted, minimally-invasive THR in a lateral decubitus position. Int Orthop. 2011;35(6):809–815. doi: 10.1007/s00264-010-1042-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Snyder GM, Lozano Calderon SA, Lucas PA, Russinoff S. Accuracy of computer-navigated total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(3):415–420. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2011.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steppacher SD, Tannast M, Zheng G, Zhang X, Kowal J, Anderson SE, et al. Validation of a new method for determination of cup orientation in THA. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(12):1583–1588. doi: 10.1002/jor.20929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tiberi JV, Pulos N, Kertzner M, Schmalzried TP. A more reliable method to assess acetabular component position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(2):471–476. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2006-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wan Z, Boutary M, Dorr LD. The influence of acetabular component position on wear in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(1):51–56. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woo RY, Morrey BF. Dislocations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64(9):1295–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu J, Wan Z, Dorr LD. Quantification of pelvic tilt in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468(2):571–575. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1064-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)

(PDF 1.19 mb)