INTRODUCTION

Brucellosis is the most common zoonotic infection in the world. It is an endemic disease in many areas throughout the world. Human brucellosis is a multisystem disease that may present with a broad spectrum of clinical manifestations. The central nervous system (CNS) involvement is a rare but serious neurological complication of brucellosis. Neurobrucellosis (NB) often is underdiagnosed, which is partly because of unawareness about the disease among the treating physicians. Clinically nonacute NB is more common than acute NB. Therefore, in order to better understand the nonacute NB, we summarized 14 cases, aimed to shed light to detailed neurologic features of nonacute NB, as well as their laboratory findings.

METHODS

In this retrospective study conducted between January 2009 and October 2014, 14 patients older than 15 years of either sex with nonacute NB who were admitted to the Department of neurology of Xuanwu Hospital, Capital Medical University, China were evaluated.

The diagnosis of NB required to fulfill the following specific criteria:[1] (1) Clinical features of illness compatible with a known NB syndrome, (2) typical cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) changes (presence of >10 mg/mm3, protein levels >45 mg/dl or glucose levels <40 mg/dl or <40% of the concomitant blood glucose level), (3) positive results of serological tests (e.g., agglutination test), (4) clinical improvement after starting the appropriate treatment, and (5) inability to prove a more suitable alternative diagnosis. More than 2 months of progress were taken as nonacute NB.

All patients’ medical records were investigated in term of patients’ age, gender, occupation, other diagnoses, clinical symptoms and their duration at the time of admission, physical examination findings, laboratory inspection (including cell numbers, protein amount, and glucose level of CSF), radiological findings.

RESULTS

Fourteen patients with nonacute NB were included in the study. The mean age was 42.4 ± 11.9 (20–64) years, and 2 (14.3%) of the patients were females, 12 (85.7%) were males. 13 (92.9%) patients had a history of consumption of unpasteurized dairy products or contacting with infected animals as occupational exposure.

A total of 6 (42.9%) patients were admitted with headache and 11 (78.6%) with gait disturbance. 7 (50%) patients had urination disorders and 8 (57.1%) patients had hearing loss. 4 (28.6%) patients had tendon hyporeflexia, 4 (28.6%) patients had tendon hyperreflexia. 8 (57.1%) patients had fever, 3 (21.4%) patients had neck stiffness. 1 (7.1%) patient had hepatosplenomegaly and 5 (35.7%) patients had a loss of weight. In our cases, there were 8 (57.1%) patients with meningitis, 5 (35.7%) patients with meningoencephalitis. Cranial nerve (CN) involvement was seen in 8 (57.1%) patients.

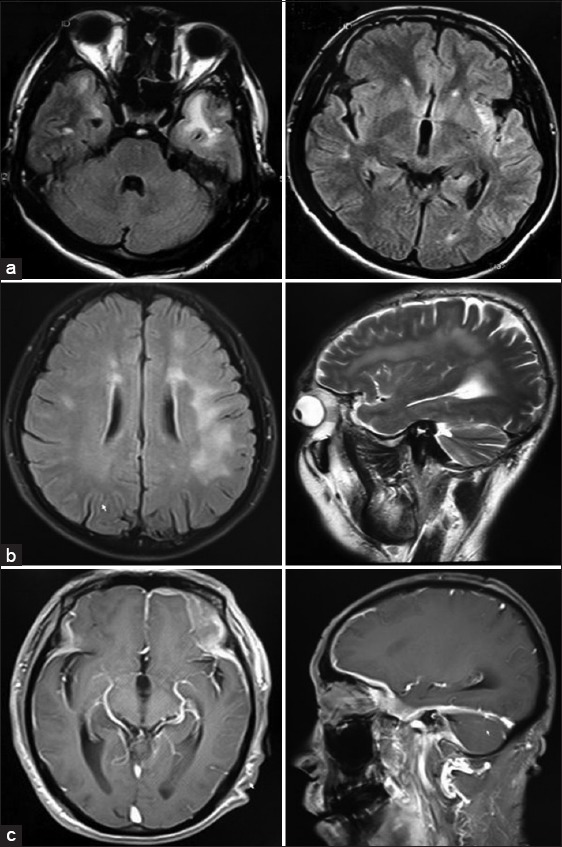

The findings of CSF examination and imaging are shown in Table 1. CSF analysis findings confirmed lymphocytic pleocytosis in 13 patients (10–360 cells/mm3; 121.4 ± 108.5), increased CSF protein level in all patients (108–400 mg/dl; mean 208.1 ± 82.7), decreased CSF glucose level in all patients (14–47 mg/dl; mean 26.4 ± 8.9), increased CSF-IgG level in all of the 9 tested patients (11.4–172.0; 66.0 ± 45.8), increased 24 h IgG synthesis rate in all of the 9 tested patients (32.6–415.9; 184.7 ± 138.7). Positive oligoclonal bands (OBs) were found in all of the 9 (100%) tested patients. All patients had positive agglutination tests for brucellosis. On cranial magnetic resonance imaging, abnormal signal in subcortical or periventricular white matter was found in 5 (35.7%) patients [Figure 1a and 1b], meningeal enhancement was found in 4 (28.6%) patients [Figure 1c].

Table 1.

Results of cerebrospinal fluid examination and magnetic resonance image of 14 patients with nonacute NB

| Patient number | CSF pressure (mm H2O) | CSF cell count/mm3 (lymphocytes %) | CSF protein (mg/dl) | CSF/blood glucose level (mg/dl) | CSF-IgG | 24 h IgG synthesis rate | OB | Imaging findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150 | 92 (95) | 255 | 20/94 | 79.0 | 63.45 | + | MRI–cranial: Patchy abnormal signal in anterior horn of lateral ventricle |

| 2 | 155 | 335 (99) | 289 | 17/157 | 79.0 | 375.7.0 | + | MRI–cranial: Meningeal reinforcement MRI–spine: Spinal meningeal reinforcement in cervical segment, abnormal signal between T9 and conus medullaris |

| 3 | 210 | 76 (96) | 136 | 25/111 | 35.0 | 121 | + | MRI–cranial: Abnormal signal in cortex and subcortical white matter of frontal temporal and insula lobes |

| 4 | 260 | 22 (82) | 108 | 30/78 | 11.4 | 32.63 | + | MRI–cranial: Abnormal signal in cortex and subcortical white matter of frontal temporal and insula lobes |

| 5 | 140 | 78 (99) | 240 | 23/122 | 66.4 | 136.58 | + | MRI–cranial: Lesion in subcortical white matter of left frontal and parietal lobes, lesion in right parietal lobe |

| 6 | 290 | 3 (–) | 234 | 14/109 | 35.0 | 70.78 | + | MRI–cranial: Hydrocephalus, leptomeningeal reinforcement |

| 7 | 60 | 65 (98) | 400 | 22/93 | 172.0 | 415.90 | + | MRI–cranial: Ventriculomegaly; meningeal reinforcement in brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord |

| 8 | 180 | 360 (90) | 248 | 32/101 | None | None | None | MRI–cranial: Normal |

| 9 | 210 | 136 (93) | 196 | 17/90 | None | None | None | MRI–cranial: Normal |

| 10 | 290 | 155 (80) | 185 | 37/97 | None | None | None | None |

| 11 | 150 | 50 (90) | 122 | 27/88 | None | None | None | MRI–cranial: Abnormal signal in subcortical white matter of frontal parietal lobes and bilateral corona radiata |

| 12 | 240 | 10 (–) | 255 | 33/80 | None | None | None | MRI–cranial: Normal |

| 13 | 130 | 79 (90) | 115 | 25/113 | 49.0 | 179.60 | + | MRI–cranial: Normal |

| 14 | 165 | 48 (98) | 131 | 47/164 | 67.3 | 267 | + | MRI–cranial: Dura thickening reinforcement of bilateral frontal temporal lobes, occipital slope and tentorium cerebelli |

NB: Neurobrucellosis; CSF: Cerebrospinal fluid; OB: Oligoclonal bands; MRI: Magnetic resonance imaging.

Figure 1.

(a) Patient 3 – Brain fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) magnetic resonance images (MRIs) show increased signal intensity in bilateral temporal lobes and left insular lobe; (b) Patient 5 – Brain FLAIR (left) and T2-weighted (right) MRIs show increased signal intensity in subcortical white matter of bilateral frontal and parietal lobes; (c) Patient 14 – Gadolinium-enhanced T1-weighted Brain MRIs show Dura thickening reinforcement of bilateral frontal temporal lobes and tentorium cerebelli.

DISCUSSION

Brucellosis is a common zoonotic endemic disease in the world and a significant health problem in Middle East, Central Asia, Africa, and Latin America. NB is an important complication of brucellosis. The exact mechanism by which the organism reaches nervous system is still uncertain, but after gaining entry into the body, it invades the reticuloendothelial system from where it reaches the blood stream, causing bacteremia, and later reaches the meninges. When the host immunity declines, the organism proliferates and invades other nervous system structures. We present a series of patients with nonacute NB focused on a detailed description of observed clinical and laboratory findings.

Neurobrucellosis is uncommon, developing in <5% of patients with Brucella infection and producing diverse neurological syndromes. Positive blood and CSF cultures can prove the diagnosis but with a low sensitivity especially in chronic brucellosis. On the other hand, cultures require a longer time to detect the organisms. Considering the above fact, culture is not the best choice for diagnosis; the diagnosis is generally based on serological methods, such as hemagglutination tests. The pathogenesis of NB is suspected to be either due to the direct effect of the organism or its toxin on the various components of the nervous system.

In NB, the nervous system may be affected both in acute and chronic stage of the disease. Clinical presentation includes meningitis, meningoencephalitis, meningovascular involvement, peripheral neuropathy, radiculopathy, and demyelinating disease.[2] Among clinical manifestations, meningitis and meningoencephalitis have been the most common clinical forms, occurring in almost 50% of the cases. In our cases, there were 13 patients (92.9%) with meningitis and meningoencephalitis, which is distinctly more than previous reports. CSF of NB patients reveals a lymphocytic pleocytosis with elevated protein in almost all of the cases with low glucose levels in one-third.[3] 13 patients (92.9%) were found in our cases with low glucose level, which is also comparatively more than the previous literature. In CSF examination of 9 patients, IgG, 24 h IgG synthesis rate, OB were tested and a 100% increase in IgG, 24 h IgG synthesis rate and a 100% positive OB were found, which was not much discussed in previous articles and might as well be an important characteristics of NB. As noted in previous reports, neck stiffness occurs in less than one-half of patients with meningitis. In our cases, neck stiffness or Kernig's and Brudzinsky's signs were observed only in 3 (21.4%) patients. As a result of basal meningitis, involvement of one or more CNs was seen in more than 50% of the NB cases. The most common cranial neuritis of NB is vestibuloacoustic neuritis. Hearing loss in NB may develop following involvement of the central auditory pathways. One of the most important differential diagnoses for NB is tuberculosis because of their similar clinical features and neuroimaging findings. Guven et al.[4] thought hearing loss due to vestibulocochlear nerve involvement seems to be unique for brucellosis and suggested electrophysiological studies (brainstem auditory-evoked potentials) should be performed more commonly to detect subclinical vestibulocochlear nerve involvement, as it may assist in pointing toward the diagnosis of neurobrucellosis. Abducens nerve is the second vulnerable CN because it has the longest intracranial course and is, therefore, susceptible to direct or indirect insult like microvascular infarction or direct compression. Finally, the involvement of seventh CN came in third among CN complications. Papilledema, which may lead to blurring of vision, has also been reported in NB. In our cases, 8 (57.1%) patients had hearing loss, and only 1 (7.1%) patient had diplopia because of abducens palsy and 1 (7.1%) patient had a loss of vision. Brucellar CN palsies usually resolve completely with the administration of antibiotics, whereas those with chronic CNS infections often have permanent neurologic deficits.

In general, three types of imaging abnormalities in CNS are seen in NB: Inflammation, white matter changes, and vascular insult.[5] White matter changes in brain manifest as hyperintense lesions on T2-weighted imagings. The first pattern is a diffuse appearance affecting the arcuate fibers region, the second one is periventricular and the third one is a focal demyelinated appearance. The nature and cause of these white matter changes may be due to an autoimmune reaction. Meanwhile, white matter changes seen in NB may mimic other inflammatory or infectious diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, or Lyme disease. In our case, we noted both inflammation (meningeal enhancement in case 2, 6, 7, 14) and white matter changes (case 1, 3, 4, 5, 11).

In conclusion, brucellosis has been a common and major health problem in developing countries. Variable clinical and imaging manifestation of NB makes clinical diagnosis more complicated and one should always keep in mind of these diverse clinical or radiological presentations of NB. For patients with atypical nervous system symptoms from brucellosis epidemic areas, NB should be considered when identifying the cause. Although the fatality rate of NB is low, early diagnosis and treatment is very important. Otherwise, it will lead to lifelong disability.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yi Cui

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Haji-Abdolbagi M, Rasooli-Nejad M, Jafari S, Hasibi M, Soudbakhsh A. Clinical and laboratory findings in neurobrucellosis: Review of 31 cases. Arch Iran Med. 2008;11:21–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adaletli I, Albayram S, Gurses B, Ozer H, Yilmaz MH, Gulsen F, et al. Vasculopathic changes in the cerebral arterial system with neurobrucellosis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:384–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajan R, Khurana D, Kesav P. Teaching neuroimages: Deep gray matter involvement in neurobrucellosis. Neurology. 2013;80:e28–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31827deb63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guven T, Ugurlu K, Ergonul O, Celikbas AK, Gok SE, Comoglu S, et al. Neurobrucellosis: Clinical and diagnostic features. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1407–12. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bektas O, Ozdemir H, Yilmaz A, Fitöz S, Ciftçi E, Ince E, et al. An unusual case of neurobrucellosis presenting as demyelination disorder. Turk J Pediatr. 2013;55:210–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]