Bacillus megaterium, a Gram-positive, aerobic, spore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium, has been found in widely diverse habitats and has been widely used as a source of recombinant protein in the industry.[1] With a cell length of up to 4 μm and a diameter of 1.5 μm, B. megaterium belongs to one of the largest known bacteria.[2]

To the best of our knowledge, B. megaterium has not been reported as the cause of brain abscesses, and infections caused by this bacterium are rare. For example, in 2006, Ramos-Esteban et al. reported the case of a 23-year-old man who developed delayed onset of lamellar keratitis caused by B. megaterium after an eye surgery.[3] In addition, in 2011, Duncan and Smith reported a 25-year-old woman who had a primary cutaneous infection caused by this bacterium most likely through microabrasions in the skin.[4] Here, we reported a case of brain abscess caused by B. megaterium in a Chinese woman.

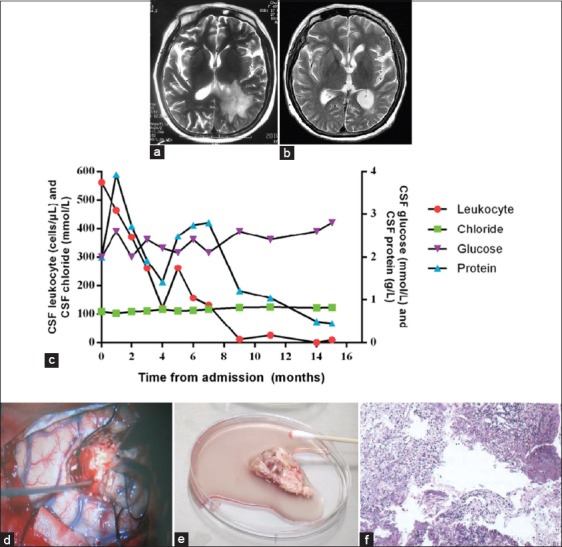

On October 1, 2012, a 50-year-old woman with psoriasis was transferred to Peking Union Medical College Hospital (Beijing, China), with a 3-month history of fever and headache. She was in her usual state of health until July 2012, when she experienced a moderate (38–39°C) fever, right visual field defect, paralysis in the right extremities, headache, and vomiting. The patient's medical history was notable for psoriasis, and she was treated with oral corticosteroids (unknown category and dosage) for 1 month in July 2012. A lumber puncture showed an intracranial pressure of 270 mmH2O, a white blood cell count of 2080/μl with 81.5% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and elevated protein levels of 1.9 g/L in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). The CSF culture was negative. A magnetic resonance image (MRI) of the brain demonstrated lumpy enhancing lesions of T1-weighted imaging hypointense signal and slight T2-weighted imaging hyperintense signals in the left parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes as well as the ventriculitis [Figure 1a]. A needle biopsy of the lesions in the parietal lobe demonstrated chronic inflammation with scattered multinucleated giant cells. The patient was diagnosed with an intracranial infection at the outside hospital and treated with cephalosporins, vancomycin, fluconazole, and amphotericin for 1 month. Her health deteriorated with recurrent fever and headache despite the aforementioned medications, and she was transferred to our department.

Figure 1.

(a) In August 2012, brain magnetic resonance image (MRI) demonstrated lumpy enhancing lesions of T1-weighted imaging hypointense signals and slight T2-weighted imaging hyperintense signals in the left parietal, temporal, and occipital lobes as well as the ventriculitis; (b) In December 2013, brain MRI demonstrated the lesions resolved after surgical excision and antibiotic use; (c) Serial cerebral spinal fluid findings; (d) Appearance of the brain abscess during the operation; (e) Brain abscess specimen; (f) Brain specimen showing the small abscess in December 2012.

At admission, on October 7, 2012, complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, immunoglobulin levels, autoimmune antibodies, and a T-SPOT. TB test were within normal ranges. A CSF analysis showed a white blood cell count of 560 cells/μl with 78% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, protein 2.0 g/L, glucose 2.0 mmol/L, and chlorine 108 mmol/L [Figure 1c]. CSF culture was negative. We reviewed the brain biopsy specimen conducted at the outside hospital, which had shown an inflammatory granuloma. The patient was empirically treated with ceftazidime and vancomycin. The differential diagnosis at that stage was broad and included chronic bacterial infection, tuberculosis (TB), fungal infection, and neurosyphilis.

On October 9, 2012, the CSF tested positive for rapid plasma reagin (RPR). The patient, therefore, was suspected to have neurosyphilis, and was treated with ceftriaxone. On re-examination with RPR and a treponeme-specific test, we found that her CSF was negative, and neurosyphilis was subsequently excluded. She was suspected to have chronic bacterial cerebromeningitis, and was therefore treated with ceftriaxone and moxifloxacin.

On October 29, the patient still experienced fever and headaches; thus, we suspected that she had TB cerebromeningitis since the pathological examination had revealed a granuloma, and the broad-spectrum antibiotics did not alleviate her symptoms. Moreover, TB was the most common cause of chronic cerebromeningitis in China. We subsequently stopped ceftriaxone, and initiated diagnostic anti-TB therapy, which included isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol, moxifloxacin, and amikacin.

On December 7, 2012, a repeated MRI demonstrated that the lesions remained unchanged. In addition, the patient's CSF was still abnormal. Stereotactic partial resection (3 cm × 3 cm) of the lesion was then performed on December 24, 2012 [Figure 1d and e]. Brain tissue was grinded in 1 ml of sterile nutritious broth by using a tissue grinder. The tissue-broth suspension was injected into aerobic and anaerobic blood culture bottles (BACTEC, Becton Dickinson, USA), and then incubated in automatic blood culture instrument (BACTEC9120). B. megaterium was cultured from the brain specimens after a 17-h incubation [Table 1]. The histological results demonstrated inflammation with small abscesses [Figure 1f]. Following this discovery, the patient was diagnosed with brain abscesses caused by B. megaterium and was treated with amoxicillin-potassium clavulanate and moxifloxacin.

Table 1.

The results of the culture of the brain tissue specimens

| Antibiotics | Results (mm) |

|---|---|

| Linezolid | 27 |

| Ampicillin/sulbactam | 24 |

| Erythromycin | 25 |

| Clindamycin | 6 |

| Penicillin | 19 |

| Teicoplanin | 17 |

| Cefuroxime | 22 |

| Rifampin | 21 |

| Gentamycin | 28 |

| Levofloxacin | 27 |

| Oxacillin | 8 |

| Vancomycin | 21 |

| Cefoxitin | 21 |

| TMP/SMZ | 22 |

Bacillus megaterium, the alarm time of culture was 17 h. TMP: Trimethoprim; SMZ: Sulfamethoxazole.

After surgery, the patient's fever and neurological symptoms remitted, and the antibiotics were switched to penicillin on March 3, 2013 (4MU intravenous drip every six hours) [Figure 1b], until her CSF was normal [Figure 1c], and the cerebral MRI was stable. Penicillin was discontinued in November 2013, and the patient has been stable ever since December 2013.

We report a rare case of a B. megaterium-related brain abscess, which is the first adult brain abscess of this etiology described in the medical literature. Antibiotic therapy combined with surgical resection is considered crucial for successful treatment of large brain abscess. This case highlights the need for early microbiological diagnosis of brain abscesses to identify unusual pathogens when there is no response to empirical antibiotics.

Since the incubation time of B. megaterium of our patient was <48 h during bacterial culture, and long-term antimicrobial therapy and excision of the lesions were effective in alleviating her symptoms, we determined that B. megaterium was the culprit of the brain abscess. Importantly, when this bacterium is found in clinical laboratory specimens, it is often reported as “insignificant contaminant”.[4] However, this case report proves that chronic brain abscesses can be caused by B. megaterium.

When histological results demonstrate granulomatous lesions but cultures are negative, intracranial space-occupying lesions are difficult to diagnose. Intracranial granuloma can be due to the response to infection, of which TB is the most common cause. Moreover, fungal lesions are also a well-documented cause. Of the various types of brain granulomas, neurosyphilis (cerebral gummas) is very rare but has been reported. Systemic granulomatous diseases, including sarcoid and Wegener's granulomatosis may have central nervous system (CNS) involvement. The differential diagnosis for our patient was challenging at admission, and she had been misdiagnosed with neurosyphilis and TB. Thus, chronic bacterial infection by B. megaterium should be considered when histological results demonstrated granulomatous lesions. We found the brain abscess caused by B. megaterium first presented as a granulomatous lesion, and later as a small abscess.

In our patient, the spreading route of B. megaterium was unclear. We hypothesize that the bacterium entered into her bloodstream and later localized to the brain. The infection had progressed significantly over a long period since the patient had not sought immediate medical attention. Therefore, the initial management of the patient at the clinic was suboptimal. Although antibiotics were effective on B. megaterium, the bacterium could already have had formed spores, and thus it was difficult to eradicate.

The ideal management of B. megaterium infections in the CNS is currently unknown due to the small number of cases in the literature. We postulate that if the organism is susceptible to penicillin, it will be a reasonable choice to treat CNS infection because it passes the blood-brain barrier. The successful treatment of our patient was mostly ascribed to surgical excision of the lesions. Taken together, we suggest that surgical resection of the brain abscess and the culture of tissue is necessary in cases where antibiotics are not effective.

There are limited data available for the treatment of brain abscess caused by B. megaterium, and thus, careful follow-up is necessary. The successful treatment of our patient was ascribed to surgical excision of the lesions and the effective antibiotic therapy.

Footnotes

Edited by: Yi Cui

Source of Support: This work was supported by National Key Technologies R and D Program for the 12th Five-year Plan (No. 2012ZX10001003).

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Vary PS, Biedendieck R, Fuerch T, Meinhardt F, Rohde M, Deckwer WD, et al. Bacillus megaterium – from simple soil bacterium to industrial protein production host. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;76:957–67. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1089-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunk B, Schulz A, Stammen S, Münch R, Warren MJ, Rohde M, et al. A short story about a big magic bug. Bioeng Bugs. 2010;1:85–91. doi: 10.4161/bbug.1.2.11101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ramos-Esteban JC, Servat JJ, Tauber S, Bia F. Bacillus megaterium delayed onset lamellar keratitis after LASIK. J Refract Surg. 2006;22:309–12. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20060301-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duncan KO, Smith TL. Primary cutaneous infection with Bacillus megaterium mimicking cutaneous anthrax. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:e60–1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2011.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]