Abstract

The steroid receptor (SR) complex contains FKBP51 and FKBP52, which bind to tacrolimus (TAC) and cyclophilin 40, which, in turn, bind to cyclosporine (CYA); these influence the intranuclear mobility of steroid–SR complexes. Pharmacodynamic interactions are thought to exist between steroids and calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) on the SR complex. We examined the effect of CNIs on steroid sensitivity. Methylprednisolone (MPSL) sensitivity was estimated as the concentration inhibiting mitosis in 50% (IC50) of peripheral blood mononuclear cells and as the area under the MPSL concentration–proliferation suppressive rate curves (CPS-AUC) in 30 healthy subjects. MPSL sensitivity was compared between the additive group (AG) as the MPSL sensitivity that was a result of addition of the proliferation suppressive rate of CNIs to that of MPSL and the mixed culture group (MCG) as MPSL sensitivity of mixed culture with both MPSL and CNIs in identical patients. IC50 values of MPSL and cortisol sensitivity were examined before and 2 months after CNI administration in 23 renal transplant recipients. IC50 and CPS-AUC values of MPSL were lower in the MCG than in the AG with administration of TAC and CYA. The CPS-AUC ratio of MCG and AG was lower in the TAC group. IC50 values of MPSL and cortisol tended to be lower after administration of TAC and CYA, and a significant difference was observed in the IC50 of cortisol after TAC administration. Steroid sensitivity increased with both TAC and CYA. Furthermore, TAC had a greater effect on increasing sensitivity. Thus, concomitant administration of CNIs and steroids can increase steroid sensitivity.

Key words: Steroid sensitivity, Pharmacodynamic interaction, Calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs), Tacrolimus (TAC), Cyclosporine (CYA)

INTRODUCTION

Current early stage immunosuppressant therapy in renal transplants generally consists of a four-drug combination therapy centered on calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs) and includes the antimetabolite mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), steroids, and basiliximab, an anticluster of differentiation 25 (CD25) antibody. CNIs and steroids are combined not only in renal transplants but also regularly combined for many types of organ transplants, although their clinical pharmacodynamic interaction has not yet been examined. The CNI-binding proteins FK506-binding protein (FKBP) 51 and FKBP52 (5), as well as cyclophilin 40 (Cyp40) (8) exist in steroid receptor (SR) complexes. Since these influence the affinity and intranuclear mobility of steroid–SR complexes, it is believed that steroids and CNIs [tacrolimus (TAC) and cyclosporine (CYA)] interact at the SR complex level (3,4,7,10,12,14–16,19). That is, while it is thought that the steroid sensitivity of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) is influenced by TAC binding to FKBP51 and FKBP52 and CYA to Cyp40 (5,8), how this influences clinical immunosuppressant therapy in organ transplants remains unclear.

The approval of the protein kinase inhibitor everolimus in Japan will likely lead to a variety of combination therapies. Thus, a full understanding of the pharmacodynamic interactions of these drugs would be valuable for evaluating comprehensive immunosuppressant effects. Therefore, we investigated 1) the influence of CNIs on the steroid sensitivity of PBMCs and 2) steroid sensitivity in renal transplant patients before and after coadministration (before and after transplant) of CNIs.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Effects of CNIs on Steroid Sensitivity of PBMCs in Healthy Subjects

Subjects

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences, and informed consent was obtained from all healthy subjects. This study was performed from September 2010 to December 2010. Effects of CNIs on steroid sensitivity of PBMCs in 30 healthy subjects (14 males and 16 females) aged 22.9 ± 1.8 years (average ± SD) were assessed.

Sensitivity Test of PBMCs (6,17)

Venous blood was taken from each subject and heparinized (Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). The heparinized blood (10 ml) was layered on 3 ml of Ficoll-Hypaque solution (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) and centrifuged at 1,300 × g for 15 min, and the PBMCs, including lymphocytes, were separated. The cells were washed and resuspended in Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 medium (Gibco Laboratories, Rockville, MD, USA), containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco Laboratories), 100,000 IU/L penicillin G (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan), and 100 mg/L streptomycin (Invitrogen), to a final density of 1 × 106 cells/L. The cell suspension (200 µl) prepared was placed in 96 flat-bottom wells of a microtiter plate (AGC Techno Glass CO., Shizuoka, Japan). Concanavalin A (Seikagaku Kogyo Co., Tokyo, Japan) was added to each well as the mitogen to activate mainly T-cells, to achieve a final concentration of 5.0 µg/ml. Subsequently, 4 µl of an ethanol solution (Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Osaka, Japan) containing methylprednisolone (MPSL) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the wells to give final concentrations of 0.1, 1, 10, 100, and 1,000 µg/L; to the control well, 4 µl of ethanol was added. The plate was incubated for 96 h at 37°C in a humidified chamber containing 5% CO2. The cells were pulsed with 18.5 kBq/well of [3H]thymidine (GE Healthcare Japan, Hino, Japan) for the last 16 h of incubation, collected on a glass-fiber filter paper (Futabe Medical, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) by using a multiharvester (Futabe Medical, Inc.), and dried. The radioactivity on the filter paper was further processed for liquid scintillation counting (Hitachi Aloka Medical, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). We determined the mean from triplicate counts obtained for each sample. The concentration–proliferation suppressive curves (CPS-AUC) of MPSL were generated. The concentration of MPSL that could inhibit 50% of PBMC mitosis (IC50) and the MPSL CPS-AUCs were determined from the concentration–response curve.

Estimation of Effects on Steroid Sensitivity of CNIs for PBMCs

After determining the CPS-AUC for MPSL alone in the PBMC sensitivity test described above, CPS-AUCs were calculated for the CNIs [TAC (Astellas Co., Tokyo, Japan) and CYA (Novartis Co., Basel, Switzerland)] with the same method. Proliferation suppression rates were then determined from the curves for each CNI concentration (three concentrations each: TAC 0.1, 0.175, and 0.25 ng/ml; CYA 5, 10, and 25 ng/ml). The CNI concentrations were decided in preliminary testing as the concentrations at which the CPS-AUC was maintained during combination cultures. The CPS-AUC obtained by adding the proliferation suppression rate of these CNI concentrations to the steroid CPS-AUC served as the additive group (AG), while the CPS-AUC determined from a combined culture of steroids and the same CNI concentrations used in the AG served as the mixed culture group (MCG). MPSL sensitivity was assessed by comparing IC50 and CPS-AUC values between AG and MCG in identical subjects. If the MPSL IC50 and CPS-AUC values in MCG were found to be lower than in the AG, the CNI was determined to have a pharmacodynamic strengthening action on steroids.

To compare the pharmacodynamic interaction of TAC and CYA on steroid sensitivity, AG to MCG ratios (AG/MCG) for IC50 and CPS-AUC values were calculated and compared at three concentration ratios (titer ratios): 0.25 ng/ml:5 ng/ml (TAC:CYA = 1:20), 0.1 ng/ml:5 ng/ml (TAC:CYA = 1:50), and 0.25 ng/ml:25 ng/ml (TAC:CYA = 1:100).

Statistical Analysis

Significant differences between IC50 and CPS-AUC values in the AG and MCG were determined using the statistical analysis software JMP version 8 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used, with significance determined at p < 0.05.

Comparison of Steroid Sensitivity of PBMCs Before and After CNI Administration in Renal Transplant Recipients

Subjects

The subjects were 23 patients (16 men, 7 women, mean age 44.6 ± 11.2 years) who received renal transplants from August 2008 to March 2012 at Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center (Table 1). Eleven patients were administered TAC, and 12 received CYA. Table 1 shows the mean ages, genders, and immunosuppressants used 2 months posttransplant for the TAC-administered and CYA-administered patients. One of the TAC-administered recipients was measured only for MPSL sensitivity. This study was a subanalysis of research of steroid withdrawal based on steroid sensitivity for PBMC that was approved by the ethics committee of Tokyo Medical University Hachioji Medical Center, and consent from the patients was obtained in writing.

Table 1.

Comparison of Steroid Sensitivity of PBMCs Before and After Coadministration of CNIs in Renal Transplant Recipients

| TAC-Administered Recipients (n = 11) | CYA-Administered Recipients (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 47.5 ± 12.5 | 42.2 ± 8.6 |

| Gender (male/female) | 7/4 | 9/3 |

| Body weight (kg) | 56.1 ± 10.7 | 66.8 ± 16.3 |

| Donor (living/cadaver) | 11/0 | 12/0 |

| ABO blood type (compatibility/incompatibility) | 9/2 | 12/0 |

| HLA mismatches (A, B, DR) | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 2.4 ± 0.9 |

| Immunosuppressive drug 2 months after renal transplantation | ||

| Dose of MPSL (off/2 mg/4 mg/8 mg) | 2/6/1/2 | 1/11/0/0 |

| Dose of MPSL (mg/day) | 3.3 ± 3.0 | 1.8 ± 0.6 |

| Dose of CNI (mg/day) | 8.5 ± 5.4 | 171 ± 61 |

| Blood trough level of CNI (ng/ml) | 7.1 ± 2.6 | 129.0 ± 44.1 |

| MMF/MIZ/MMF + MIZ/non | 7/2/1/1 | 8/3/1/0 |

PBMCs, peripheral blood mononuclear cells; CNIs, calcineurin inhibitors; TAC, tacrolimus; CYA, cyclosporine; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; MPSL, methylprednisolone; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MIZ, mizoribine.

Immunosuppressive Therapy

Immunosuppressive induction therapy was carried out using a combination of CNI, steroid, antimetabolite drugs, and anti-CD25 antibody. MPSL, CNI, and antimetabolite administration began 3 days before the surgery. MPSL (Medrol; Pfizer Co., Groton, CT, USA) was initially dosed at 48 mg/day and then reduced gradually to zero in the second month after the operation. Some patients continued on a dose of 4 mg/day or less, depending on their condition. CNI began at 0.25 mg kg−1 day−1 for TAC (Prograf cap., Astellas Co.) and 6 mg kg−1 day−1 for CYA (Neoral cap., Novartis Pharma Co.) and was then adjusted based on blood trough levels. Dose was adjusted to achieve target trough levels of about 10–15 ng/ml for TAC and about 150–200 ng/ml for CYA by 2 months after the transplant. The antimetabolite MMF (Cellcept 250 mg cap., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was dosed at 1,000–1,500 mg/day and mizoribine (Bredinin tab., Asahi Kasei Co., Tokyo, Japan) at 6 mg kg−1 day−1. Basiliximab (Simulect, Novartis Pharma Co.) at 20 mg/day was administered twice: on the day of the transplant and on day 4 postoperatively. Blood was collected before the transplant and prior to starting immunosuppressants. The immunosuppressant therapies at 2 months after transplantation are listed in Table 1.

Evaluation of Steroid Sensitivity to PBMCs

Blood was collected 4 days before transplant for the sample prior to CNI administration (pretransplant) and 2 months after transplant for the sample after CNI administration (posttransplant). The posttransplant blood collection was done before the immunosuppressants were taken.

Based on the PBMC sensitivity experiment described above, sensitivities to PBMCs (IC50) of the endogenous steroid cortisol (COR) (Sigma-Aldrich) and the steroid drug MPSL were determined. Then, the influence of CNIs on steroid sensitivity was evaluated by comparing the IC50 of the steroids before and 2 months after CNI (TAC, CYA) administration. Further, steroid (COR, MPSL) IC50 values were compared between patients who were administered CNIs in combination as TAC or CYA.

Statistical Analysis

We used two-tailed paired t tests or Wilcoxon signed rank test to compare IC50 values of MPSL and COR from before and 2 months after renal transplantation. These analyses were performed using JMP version 8.0. In each case, p < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

RESULTS

Effects on Steroid Sensitivity of CNIs for PBMCs in Healthy Subjects

Comparison of IC50 of MPSL Between Additive Group and Mixed Culture Group

As shown in Table 2, the MPSL IC50 was significantly lower (p < 0.05) in the MCG than in the AG for all TAC and CYA concentrations, showing that combined use of both TAC and CYA has a strengthening action on steroid sensitivity.

Table 2.

Comparison of IC50 of MPSL Between Additive Group and Mixed Culture Group in 30 Healthy Subjects

| CNI | Concentration (ng/ml) | Additive Group Median (Range) | Mixed Culture Group Median (Range) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAC | 0.1 | 9.05 (0.71–53.77) | 4.69 (2.94–8.51) | <0.05 |

| 0.175 | 9.25 (0.10–51.03) | 0.74 (0.10–4.53) | <0.05 | |

| 0.25 | 6.15 (0.10–35.69) | 0.10 (0.10–2.51) | <0.05 | |

| CYA | 5 | 34.49 (5.35–77.73) | 8.58 (5.53–32.75) | <0.05 |

| 10 | 7.86 (0.34–48.99) | 3.78 (0.59–5.65) | <0.05 | |

| 25 | 2.63 (0.10–19.23) | 0.13 (0.10–0.78) | <0.05 |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Comparison of CPS-AUC of MPSL Between Additive Group and Mixed Culture Group

Similar to the IC50 results, Table 3 shows the CPS-AUC of MPSL to be significantly lower in the MCG compared to the AG for all TAC and CYA concentrations (p < 0.05), showing that combined use of both TAC and CYA strengthens steroid sensitivity.

Table 3.

Comparison of CPS-AUC of MPSL Between Additive Group and Mixed Culture Group in 30 Healthy Subjects

| CNI | Concentration (ng/ml) | Additive Group Median (Range) | Mixed Culture Group Median (Range) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAC | 0.1 | 7,235 (1,996–26,894) | 1,551 (789–5,275) | <0.05 |

| 0.175 | 3,814 (1,561–27,287) | 428 (193–1,106) | <0.05 | |

| 0.25 | 2,868 (1,315–18,451) | 271 (104–678) | <0.05 | |

| CYA | 5 | 20,042 (3,556–37,928) | 5,005 (3,255–9,609) | <0.05 |

| 10 | 3,929 (840–22,343) | 1,193 (651–3,145) | <0.05 | |

| 25 | 3,106 (383–7,095) | 477 (25–808) | <0.05 |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test. CPS-AUC, concentration–proliferation suppressive rate curves.

Comparison of IC50 Ratio and CPS-AUC Ratio of MPSL Between TAC and CYA

There was no difference in the steroid strengthening action between TAC and CYA for all IC50 titer ratios (Table 4), though there was a significant difference in the CPS-AUC ratio at the clinical titer ratio of TAC:CYA 1:20. CPS-AUC ratio was significantly lower in the TAC group (p < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 4.

Comparison of MPSL IC50 Ratio Between TAC and CYA in 30 Healthy Subjects

| Concentration (ng/ml) | Concentration Ratio (TAC:CYA) | IC50 Ratio (Additive Group/Mixed Culture Group) |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAC | CYA | TAC Median (Range) | CYA Median (Range) | ||

| 0.25 | 5 | 1:20 | 0.171 (0.036–1.000) |

0.548 (0.161–1.254) |

N.S. |

| 0.1 | 5 | 1:50 | 0.433 (0.104–1.053) |

0.548 (0.161–1.254) |

N.S. |

| 0.25 | 25 | 1:100 | 0.171 (0.036–1.000) |

0.148 (0.014–1.000) |

N.S. |

Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Table 5.

Comparison of MPSL CPS-AUC Ratio Between TAC and CYA in 30 Healthy Subjects

| Concentration (ng/ml) | Concentration Ratio (TAC:CYA) | CPS–AUC Ratio (Additive Group/Mixed Culture Group) |

p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAC | CYA | TAC Median (Range) | CYA Median (Range) | ||

| 0.25 | 5 | 1:20* | 0.080 (0.026–0.303) |

0.360 (0.233–0.863) |

<0.05 |

| 0.1 | 5 | 1:50 | 0.253 (0.136–0.687) |

0.360 (0.233–0.863) |

N.S. |

| 0.25 | 25 | 1:100 | 0.080 (0.026–0.303) |

0.096 (0.014–0.889) |

N.S. |

Concentration ratio of TAC:CYA = 1:20 is closest to the clinical titer in these concentration ratios. Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Comparison of Steroid Sensitivity of PBMCs Before and After CNI Combination in Renal Transplant Recipients

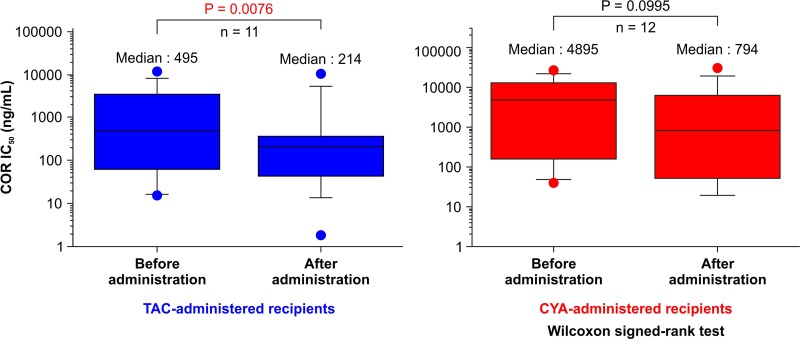

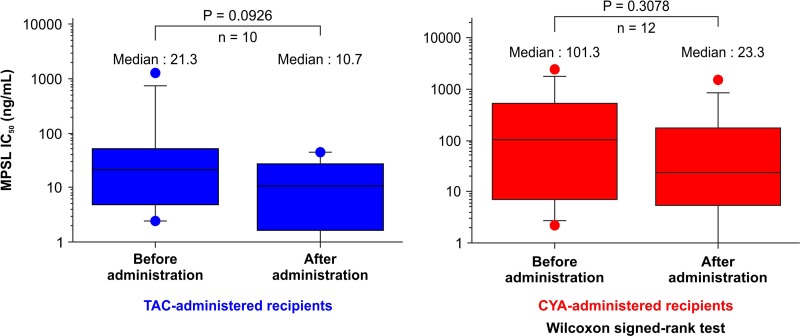

As shown in Figure 1, COR IC50 in the TAC-administered patients decreased significantly from a median (range) of 495 (15.8–11,881) ng/ml pretransplant to 214 (1.8–10,261) ng/ml posttransplant (p = 0.0076). COR IC50 exhibited a decreasing trend in the CYA-administered patients from a median (range) of 4,895 (39.6–26,254) ng/ml pretransplant to 794 (1.0–30,563) ng/ml posttransplant, though the difference was not significant (p = 0.0995). As shown in Figure 2, MPSL IC50 decreased in the TAC-administered patients from a median (range) of 21.3 (2.4–1,309) ng/ml pretransplant to 10.7 (0.1–45.1) ng/ml posttransplant, though the difference was not significant (p = 0.0926). A significant difference was not observed for MPSL IC50 in the CYA-administered patients, which was median (range) of 101 (2.2–2,468) ng/ml pretransplant and 23.3 (2.2–1,552) ng/ml posttransplant (p = 0.3078).

Figure 1.

Comparison of IC50 of COR before and after CNI administration in TAC- and CYA-administered renal transplant recipients. The dots represent the maximum and minimum values, while the squares represent the interquartile range, and the line represents the median value. COR, cortisol; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; TAC, tacrolimus; CYA: cyclosporine.

Figure 2.

Comparison of IC50 of MPSL before and after CNI administration in TAC- and CYA-administered renal transplant recipients. The dots represent the maximum and minimum values, while the squares represent the interquartile range, and the line represents the median value. MPSL, methylprednisolone.

DISCUSSION

Currently, CNIs and steroids are commonly used together in the early stages after renal transplant. Although these drugs may interact, their pharmacodynamic interaction has not received attention.

The TAC-binding proteins FKBP51 and FKBP52 are present in SR complexes, as is CYA-binding protein Cyp40 (3–5,8,14–16,19). FKBP51 is thought to suppress the intranuclear mobility of SR complexes (4,14–16), while FKBP52 is thought to promote intranuclear mobility (1,2,18). Thus, it is thought that when TAC administration inhibits FKBP, steroid sensitivity is affected by whichever of FKBP51 or FKBP52 has the larger contribution ratio. Further, as the structure of Cyp40 resembles that of FKBP52, it has been reported both that it functions similarly to FKBP52 (13) and is antagonistic to FKBP52 (11). Therefore, it was unclear whether the sensitivity would increase or decrease if Cyp40 was inhibited by CYA. Since CNI-binding proteins affect the affinity and intranuclear mobility of steroid–SR complexes, there is believed to be a pharmacodynamic interaction at the SR complex level when steroids and CNIs are used together clinically, which was examined in this study. Our investigation of CNI effect on the steroid sensitivity of PBMCs in healthy people revealed MPSL IC50 and CPS-AUC values to be significantly smaller in the MCG compared to the AG at all TAC and CYA concentrations, showing a strengthening action on the steroid sensitivity of PBMCs. Further, the examination of the effect on steroid sensitivity from CNI administration in renal transplants showed that COR IC50 was significantly lower after CNI administration (posttransplant) than before (pretransplant), indicating a possible increased steroid sensitivity. In addition, while the difference was not significant, a similar trend was observed with CYA. Davies et al. found that FKBP52 had a bigger effect than FKBP51 on steroid-binding affinity and transactivity by immunophilin ligands (2). In our results, the involvement of FKBP51 was thought to have more influence than FKBP52 on steroid sensitivity to TAC, causing it to increase. Moreover, since CYA, which is an immunophilin ligand, similarly increases sensitivity, it is possible that Cyp40 suppresses aspects such as steroid-binding affinity and transactivity.

Next, the abilities of TAC and CYA to increase steroid sensitivity were compared. In the PBMC test on healthy people, TAC had a stronger action on CPS-AUC at the clinical titer ratio of TAC:CYA 1:20. In the sensitivity test after CNI administration for renal transplants, COR IC50 exhibited a significant difference only for TAC, suggesting that TAC has a more robust strengthening action. To support this, the authors compared PBMC sensitivity to COR and MPSL as IC50 in groups administered either TAC or CYA after renal transplants and found significantly higher sensitivity to COR and MPSL in the TAC-administered group than in the CYA-administered group (9).

The above results on steroid sensitivity from in vitro combined culture tests, and before and after clinical CNI administration, suggest both TAC and CYA, when combined with steroids, increase the steroid sensitivity of PBMCs. Further, the results suggest this strengthening effect is larger with TAC. To clarify the mechanism by which CNI strengthens steroid sensitivity, we are currently investigating the effect on steroid sensitivity of knockdowns of FKBP51, FKBP52, and Cyp40 using small interfering RNA (siRNA).

In addition to renal transplants, steroids and CNIs are combined for other organ transplants and autoimmune disorders such as nephrotic syndrome. Therefore, understanding their pharmacodynamic interactions is considered important. Moreover, since the pharmacodynamic ability of CNIs to enhance steroids appears to be stronger with TAC, it is possible that lower doses of steroids could be used when combined with TAC compared with CYA.

Everolimus and other new immunosuppressants are currently being applied in various combinations in Japan. Thus, clarifying the pharmacodynamic interactions of these drugs is important for judging comprehensive immunosuppressant effects and considering future combination therapies. Among these, the CNI–steroids combination is currently in common use. As CNIs elevate steroid sensitivity and thus increase their effect, this characteristic could possibly be used to reduce steroid doses, which is clinically significant. However, it remains unclear how and to what extent steroids are affected clinically by the pharmacodynamic strengthening action of CNIs. These are topics for future study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grant No. 23590201 from the Ministry of Education of Japan. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Banerjee A.; Periyasamy S.; Wolf I. M.; Hinds T. D. Jr.; Yong W.; Shou W.; Sanchez E. R. Control of glucocorticoid and progesterone receptor subcellular localization by the ligand-binding domain is mediated by distinct interactions with tetratricopeptide repeat proteins. Biochemistry 47(39):10471–10480; 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davies T. H.; Ning Y. M.; Sánchez E. R. Differential control of glucocorticoid receptor hormone-binding function by tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) proteins and the immunosuppressive ligand FK506. Biochemistry 44:2030–2038; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Denny W. B.; Prapapanich V.; Smith D. F.; Scammell J. G. Structure-function analysis of squirrel monkey FK506-binding protein 51, a potent inhibitor of glucocorticoid receptor activity. Endocrinology 146:3194–3201; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Denny W. B.; Valentine D. L.; Reynolds P. D.; Smith D. F.; Scammell J. G. Squirrel monkey immunophilin FKBP51 is a potent inhibitor of glucocorticoid receptor binding. Endocrinology 14:4107–4113; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fretz H.; Albers M. W.; Galat A.; Standaert R. F.; Lane W. S.; Burakoff S. T.; Bierer B. E.; Schreiber S. L. Rapamycin and FK506 binding proteins (immunophilins). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:1409–1411; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirano T.; Oka K.; Takeuchi H.; Sakurai E.; Matsuno N.; Tamaki T.; Kozaki M. Clinical significance of glucocorticoid pharmacodynamics assessed by antilymphocyte action in kidney transplantation. Transplantation 57:1341–1348; 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnson J. L.; Toft D. O. A novel chaperone complex for steroid receptors involving heat shock proteins, immunophilins, and p23. J. Biol. Chem. 269:24989–24993; 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kieffer L. J.; Thalhammer T.; Handschumacher R. E. Isolation and characterization of a 40-kDa cyclophilin-related protein. J. Biol. Chem. 267:5503–5507; 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Muhetaer G.; Takeuchi H.; Akizuki S.; Unezaki S.; Iwamoto H.; Shimazu M.; Hirano T. Higher sensitivity of peripheral blood lymphocytes to endogenous glucocorticoid in renal transplant recipients treated with tacrolimus as compared to those treated with cyclosporine. Cell Med. 3:75–80; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Radanyi C.; Chambraud B.; Baulieu E. E. The ability of the immunophilin FKBP59-HBI to interact with the 90-kDa heat shock protein is encoded by its tetratricopeptide repeat domain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91(23):11197–11201; 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ratajczak T.; Carrello A. Cyclophilin 40 (CyP-40), mapping of its hsp90 binding domain and evidence that FKBP52 competes with CyP-40 for hsp90 binding. J. Biol. Chem. 271(6):2961–2965; 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ratajczak T.; Carrello A.; Minchin R. F. Biochemical and calmodulin binding properties of estrogen receptor binding cyclophilin expressed in Escherichia coli . Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 209(1):117–125; 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ratajczak T.; Ward B. K.; Cluning C.; Allan R. K. Cyclophilin 40: An Hsp90-cochaperone associated with apo-steroid receptors. Int. J. Biochem. Cell. Biol. 41:1652–1655; 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Reynolds P. D.; Ruan Y.; Smith D. F.; Scammell J. G. Glucocorticoid resistance in the squirrel monkey is associated with overexpression of the immunophilin FKBP51. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 84(2):663–669; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scammell J. G.; Denny W. B.; Valentine D. L.; Smith D. F. Overexpression of the FK506-binding immunophilin FKBP51 is the common cause of glucocorticoid resistance in three New World primates. Endocrinology 124:152–165; 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Scammell J. G.; Tucker J. A.; King J. A.; Moore C. M.; Wright J. L.; Tuck-Muller C. M. Kidney epithelial cell line from a Bolivian squirrel monkey. In Vitro Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 38:258–261; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Takeuchi H.; Matsuno N.; Hirano T.; Gulimire M.; Hama K.; Nakamura Y.; Iwamoto H.; Kawaguchi T.; Okuyama K.; Unezaki S.; Nagao T. Steroid withdrawal based on lymphocyte sensitivity to endogenous cortisol in renal transplant recipients. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 34(10):1578–1583; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tatro E. T.; Everall I. P.; Kaul M.; Achim C. L. Modulation of glucocorticoid receptor nuclear translocation in neurons by immunophilins FKBP51 and FKBP52: Implications for major depressive disorder. Brain Res. 1286:1–12; 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Westberry J. M.; Sadosky P. W.; Hubler T. R.; Gross K. L.; Scammell J. G. Glucocorticoid resistance in squirrel monkeys results from a combination of a transcriptionally incompetent glucocorticoid receptor and overexpression of the glucocorticoid receptor co-chaperone FKBP51. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 100:34–41; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]