Abstract

Background

Patients with biliary tract adenocarcinoma with nodal involvement have a poor prognosis. There is currently no standardized method for intraoperative lymph node assessment. The current study aimed to determine the prognostic significance of the highest peripancreatic lymph node (HPLN) in biliary tract malignancy.

Methods

This was a retrospective study of patients undergoing potential curative resection of biliary tract adenocarcinoma from January 1995 through December 2010 who prospectively had intraoperative sampling of the HPLN. The median follow-up was 72.8 months. The primary end points were recurrence-free survival (RFS) and disease-specific survival (DSS).

Results

The rate of HPLN positivity in 110 patients undergoing exploration for potential curative resection was 30 % and did not vary with histologic subtype (gallbladder vs. cholangiocarcinoma). Eighty-five patients underwent complete gross resection. In this subset, median RFS and DSS were 34.3 months (95 % confidence interval [CI] 23.6—not reached [NR]) and 62.4 months (95 % CI 40.8—NR) for HPLN-negative patients, and 9.6 months (95 % CI 4.76—NR) and 20.5 months (95 % CI 7.4—NR) for HPLN-positive patients (p < 0.01), respectively. Median DSS was 14.6 months (95 % CI 9.6–25.4) for patients with unresectable disease. On multivariate analysis, HPLN status was an independent predictor of RFS (hazard ratio 3.73, 95 % CI 1.86–7.45; p < 0.01) and DSS (hazard ratio 3.98, 95 % CI 1.89–8.38; p < 0.01).

Conclusions

HPLN status is prognostic of RFS and DSS in biliary tract adenocarcinoma. Intraoperative nodal staging by HPLN sampling warrants further investigation in a prospective trial.

Surgical management of biliary tract adenocarcinoma with lymph node metastases is controversial. The current American Joint Commission on Cancer (AJCC) lymph node staging system varies for different types of biliary tract cancer.1 Both N1 and N2 nodal distributions are acknowledged for gallbladder cancer and perihilar cholangiocarcinoma, whereas only N1 nodes are recognized for distal common bile duct (CBD) and intrahepatic (peripheral) cholangiocarcinoma, and nodal metastases beyond the N1 distribution are considered M1 disease. N1 nodes are regional portal nodes along the cystic duct, CBD, hepatic artery, and portal vein. N2 nodes are defined as para-aortic, superior mesenteric artery, and celiac artery nodes. It is controversial whether involvement of N2 nodes precludes curative surgery for biliary tract cancer.2,3 Many Eastern centers treat these patients with more radical resection, sometimes combining pancreaticoduodenectomy and liver resection, whereas in the West, N2 involvement is considered unresectable. There is currently no standardized method of assessment of nodal disease burden.

Multiple studies have characterized the pattern of lymphatic drainage from the gallbladder and biliary tree. The lymphatic drainage starts in pericholecysto-/choledochonodes and proceeds to retropancreatic nodes and those along the hepatic vessels and celiac artery, then on to interaortocaval and finally para-aortic nodes.4–6 The highest peripancreatic lymph node (HPLN) is a fairly constant node that sits at the junction of the CBD and the superior border of the pancreas (Fig. 1). It lies between the N1 and N2 nodal distributions. This node is routinely dissected in gaining exposure to the portal vein above the pancreas. Routine sampling of this node has been recommended as a simple means to assess for distant lymph node involvement, theorizing that it may serve as a sentinel node for N2 disease.7 There are no reported data available to date, however, on the prognostic significance of this lymph node in biliary tract adenocarcinoma.

FIG. 1.

Illustration of HPLN between N1 and N2 regions

The objective of the current study was to determine the rate of involvement of the HPLN in biliary tract cancer and to determine the prognostic significance of metastases to this node for patients undergoing curative resection. The hypothesis was that the HPLN may serve as a representative node for N2 or distant lymphatic metastases, and that HPLN involvement by metastatic cancer may be prognostic of long-term outcome.

METHODS

Patients

Patients undergoing surgery with curative intent for biliary tract adenocarcinoma with sampling of the HPLN between January 1995 and December 2010 were identified from a prospectively maintained hepatobiliary database. During this time period, HPLN sampling was performed prospectively by a single surgeon (YF). All patients underwent appropriate preoperative staging with cross-sectional imaging. Patients had no evidence of distant metastases and had potentially resectable disease. A total of 217 patients were identified. One hundred six patients who did not have the HPLN sampled and sent as a separate labeled specimen or who were undergoing palliative-intent surgery were excluded. One patient experienced 30-day mortality and was excluded, leaving 110 who were included in the study.

Surgery

Patients were taken to the operating room for exploration and resection with curative intent. For patients with gall-bladder cancer who had undergone prior cholecystectomy with T1B or greater disease on pathology and no evidence of gross disease at reexploration, resections of segment IVB and V and portal lymphadenectomy was performed. For patients with cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer that was not previously resected, cholecystectomy and hepatectomy with or without CBD resection were performed as indicated to achieve complete gross resection. Completeness of resection was classified on the basis of the surgeon’s impression and procedures were documented as palliative or potentially curative in the operative note. Patients with bulky, gross lymph node involvement were classified as having unresectable disease and procedures performed were considered palliative. Frozen section analysis of margins or lymph nodes was performed at the surgeon’s discretion. In all cases, the HPLN was identified by the surgeon and was sent to pathology as a separate specimen.

Pathology

Pathologic assessment of tissue specimens was performed as previously described.8 For specimens containing gross tumor, serial cross-sections through tumor were performed and gross tumor dimensions were determined. Bile ducts and gallbladders were opened longitudinally to determine extent of gross tumor involvement. Pathologic T stage was reported according to the AJCC staging manual (7th edition).1 Resection margin status was determined as R0, R1, or R2 (R0 = no residual disease, R1 = microscopic residual disease, R2 = macroscopic residual disease). After histologic sampling of the primary tumor, adipose tissue was removed from all primary specimens and was examined for lymph nodes. All identified nodes were sectioned and examined with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. Lymph node tissue sent separately was similarly sectioned and examined with H & E staining.

Statistical Analysis

Patient characteristics are given using the median and range for continuous variables, and frequency and percent for categorical variables. The Kruskal–Wallis test and Fisher’s test were used to compare continuous and categorical variables, respectively, stratified by HPLN status. Survival analysis was used to determine factors associated with disease-specific survival (DSS) and recurrence-free survival (RFS). Time to event was calculated from date of surgery to date of event or last follow-up. Patients without the event of interest at last follow-up were censored. Only patients with R0 or R1 resections were included in the survival analyses. The log-rank test was used to compare survival outcomes between patient characteristics. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression were used to assess the association between patient characteristics and the event of interest. All analyses were performed by R version 2.15.3.

RESULTS

All Patients

One hundred ten patients underwent operative exploration with curative intent for biliary tract adenocarcinoma with HPLN sampling between January 1995 and December 2010. Forty-seven patients (43 %) had a diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma. Of those, 15 had intrahepatic or peripheral cholangiocarcinoma, and 32 had extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (26 hilar and 6 CBD). Sixty-three patients (57 %) had gallbladder cancer. Overall, 30 patients (27 %) had a positive HPLN. The incidence of HPLN positivity was similar for patients with gallbladder cancer (29 %) and cholangiocarcinoma (26 %).

The median age was 66 years (range 34–82 years) and was similar for patients with positive or negative HPLN. Sixty-eight patients (62 %) were female and gender was also similar between HPLN positive and negative patients. For tumor-related variables, the degree of differentiation, prevalence of papillary subtype, and presence of perineural and vascular invasion were not significantly different for patients with a positive or negative HPLN. Patients in the HPLN-positive group were more likely to have unknown T stage (pTX) (23 vs. 0 %, p < 0.01), positive or unknown local LN status (23 vs. 15 % positive, 64 vs. 23 % unknown; p < 0.01), and intraoperative findings of M1 disease (33 vs. 2 %; p < 0.01). Fewer patients in the HPLN-positive group underwent complete gross resection (R0/R1) (47 vs. 89 %; p < 0.01) (Supplementary File). When considering only those patients who underwent complete gross resection (n = 85), only local lymph node status was significantly different between HPLN-negative and HPLN-positive groups, with more patients in the latter group having positive local lymph nodes (50 vs. 17 %, p = 0.01) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Clinicopathologic variables for 85 patients who underwent complete gross resection, stratified by HPLN status

| Variable | All patients (n = 85) | HPLN negative (n = 71) | HPLN positive (n = 14) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 65 (34–82) | 65 (34–82) | 66 (54–82) | 0.41 |

| Female gender | 54 (64) | 45 (63) | 9 (64) | 0.81 |

| Diagnosis | 0.97 | |||

| Gallbladder cancer | 51 (60) | 43 (61) | 8 (57) | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 34 (40) | 28 (39) | 6 (43) | |

| Pathologic T stage | 0.12 | |||

| pT1 | 14 (16) | 13 (17) | 1 (7) | |

| pT2 | 44 (52) | 39 (37) | 5 (35) | |

| pT3 | 27 (32) | 19 (27) | 8 (57) | |

| Local LN status | 0.01 | |||

| Positive | 19 (22) | 12 (17) | 7 (50) | |

| Negative | 51 (60) | 47 (66) | 4 (29) | |

| Unknown | 15 (18) | 12 (17) | 3 (21) | |

| Differentiation | 0.65 | |||

| Well | 11 (13) | 9 (13) | 2 (14) | |

| Moderate/Poor | 71 (83) | 59 (83) | 12 (86) | |

| Unknown | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 0 | |

| Perineural invasion | 0.06 | |||

| No | 23 (27) | 22 (31) | 1 (7) | |

| Yes | 41 (48) | 30 (42) | 11 (79) | |

| Unknown | 21 (25) | 19 (27) | 2 (14) | |

| Vascular invasion | 0.64 | |||

| No | 25 (29) | 21 (30) | 4 (29) | |

| Yes | 34 (40) | 27 (38) | 7 (50) | |

| Unknown | 26 (31) | 23 (32) | 3 (21) | |

| Margin status | 0.70 | |||

| R0 | 77 (91) | 64 (90) | 13 (93) | |

| R1 | 8 (9) | 7 (10) | 1 (7) |

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range); categorical variables are expressed as n (%)

HPLN highest peripancreatic lymph node

Surgery

Operative procedures performed for 85 patients with grossly resectable disease included extended cholecystectomy (n = 4) or segment IV/V resection after prior cholecystectomy (n = 37), right hepatectomy or trisegmentectomy with or without CBD resection (n = 26), right posterior sectorectomy (n = 1), left hepatectomy or trisegmentectomy with or without CBD resection (n = 14), CBD resection without hepatectomy (n = 2), and pancreaticoduodenectomy (n = 1). Procedures for 25 patients with unresectable disease included palliative cholecystectomy (n = 11), exploration and biopsy only (n = 13), and biliary bypass to segment III (n = 1). One patient who underwent palliative cholecystectomy also had placement of a hepatic artery infusion pump.

Recurrence-Free Survival

Median follow-up for the entire cohort was 72.8 months. The estimated median RFS for all patients who underwent complete gross resection (n = 85) was 25.8 months (95 % confidence interval [CI] 19.1–46.2). Median RFS was 34.3 months (95 % CI 23.6—not reached [NR]) for HPLN-negative patients and 9.6 months (95 % CI 4.76—NR) for HPLN-positive patients (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2a). All HPLN-positive patients had disease recurrence within 4 years of surgery. In contrast, three of eleven patients with only local nodes positive and negative HPLNs were alive without recurrence >50 months after surgery (data not shown). On univariate analysis, HPLN positivity was associated with recurrence (hazard ratio [HR] 4.43, 95 % CI 2.27–8.65; p < 0.01). Advanced pathologic T stage (pT3 vs. pT1) and use of adjuvant chemotherapy were also significantly associated with recurrence. No other variable analyzed, including microscopic margin positivity (R1) (HR 1.74, 95 % CI 0.73–4.11; p = 0.21) and local (N1) LN positivity (HR 1.78, 95 % CI 0.90–3.54; p = 0.10), was associated with recurrence (Table 2).

FIG. 2.

Kaplan–Meier RFS (a) and DSS (b) estimates for 85 patients who underwent complete gross resection stratified by HPLN status

TABLE 2.

Univariate and multivariate analyses of factors that may be associated with survival in 85 patients who underwent complete gross resection

| Variable | RFS

|

DSS

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95 % CI | p | HR | 95 % CI | p | |

| Univariate analysis | ||||||

| Diagnosis (gallbladder vs. cholangiocarcinoma) | 0.87 | 0.50–1.52 | 0.63 | 0.94 | 0.52–1.70 | 0.83 |

| HPLN (positive vs. negative) | 4.43 | 2.27–8.65 | < 0.01 | 4.58 | 2.26–9.25 | < 0.01 |

| Age | 1.00 | 0.97–1.03 | 0.85 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.02 | 0.65 |

| Gender (M vs. F) | 0.98 | 0.54–1.75 | 0.93 | 1.26 | 0.67–2.36 | 0.48 |

| Margin (R1 vs. R0) | 1.74 | 0.73–4.11 | 0.21 | 2.57 | 0.98–6.76 | 0.06 |

| Differentiation (well vs. moderate/poor) | 0.36 | 0.13–1.01 | 0.05 | 0.49 | 0.18–1.37 | 0.18 |

| pT stage | ||||||

| pT2 versus pT1 | 1.55 | 0.67–3.60 | 0.31 | 1.64 | 0.66–4.08 | 0.29 |

| pT3 versus pT1 | 2.62 | 1.09–6.29 | 0.03 | 2.65 | 1.04–6.75 | 0.04 |

| Local LN status (positive vs. negative) | 1.78 | 0.90–3.54 | 0.10 | 2.12 | 1.03–4.37 | 0.04 |

| Vascular invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.63 | 0.87–3.06 | 0.13 | 1.63 | 0.83–3.22 | 0.16 |

| Perineural invasion (yes vs. no) | 1.92 | 0.90–4.10 | 0.09 | 2.74 | 1.12–6.71 | 0.03 |

| Papillary subtype (yes vs. no) | 1.58 | 0.23–1.46 | 0.24 | 0.58 | 0.21–1.63 | 0.30 |

| Estimated blood loss | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.16 | 1.00 | 1.00–1.01 | 0.08 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (yes vs. no) | 1.92 | 1.08–3.42 | 0.03 | 2.14 | 1.14–4.02 | 0.02 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||||||

| HPLN (positive vs. negative) | 3.73 | 1.86–7.45 | < 0.01 | 3.98 | 1.89–8.38 | < 0.01 |

| pT stage | ||||||

| pT2 versus pT1 | 1.36 | 0.58–3.22 | 0.48 | 1.38 | 0.55–3.51 | 0.49 |

| pT3 versus pT1 | 1.85 | 0.74–4.61 | 0.19 | 1.68 | 0.62–4.49 | 0.31 |

| Margin (R1 vs. R0) | 1.40 | 0.59–3.34 | 0.45 | 2.39 | 0.90–6.33 | 0.08 |

RFS recurrence-free survival, DSS disease-specific survival, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, HPLN highest peripancreatic lymph node

A multivariate model was constructed on the basis of the results of the univariate analysis (Table 2). HPLN status, margin status, and pathologic T stage were included in the model. Adjuvant chemotherapy was not included because the decision to give adjuvant therapy was based on nodal involvement or microscopic margin positivity so this was considered a related/dependent variable. Microscopic margin status was included because it is known to be associated with recurrence. On multivariate analysis, HPLN positivity remained the only independent predictor of recurrence (HR 3.73, 95 % CI 1.86–7.45; p < 0.01).

Disease-Specific Survival

The estimated median DSS for all patients who underwent complete gross resection was 42.1 months (95 % CI 33.0–79.2). Median DSS was 62.4 months (95 % CI 4.08—NR) for those with a negative HPLN versus 20.5 months (95 % CI 7.4—NR) for those with a positive HPLN (p < 0.01) (Fig. 2b). On univariate analysis, HPLN positivity (HR 4.58, 95 % CI 2.26–9.25; p < 0.01), advanced pathologic T stage (HR 2.65, 95 % CI 1.04–6.75; p = 0.04), local LN positivity (HR 2.12, 95 % CI 1.03–4.37; p = 0.04), and use of adjuvant chemotherapy (HR 2.14, 95 % CI 1.14–4.02; p = 0.02) were associated with death from disease. Perineural invasion was also associated with death from disease but this variable was missing for 31 % of patients (Table 2).

A multivariate model was constructed on the basis of the univariate analysis results (Table 2). HPLN status, microscopic margin status, and pathologic T stage were included in the model. Adjuvant chemotherapy was considered a linked variable to nodal status and margin status so was not included. Perineural invasion was not included because data on this variable were missing for a significant proportion of patients. HPLN status was independently associated with death from disease when accounting for margin status and pathologic T stage (HR 3.98, 95 % CI 1.89–8.38; p < 0.01).

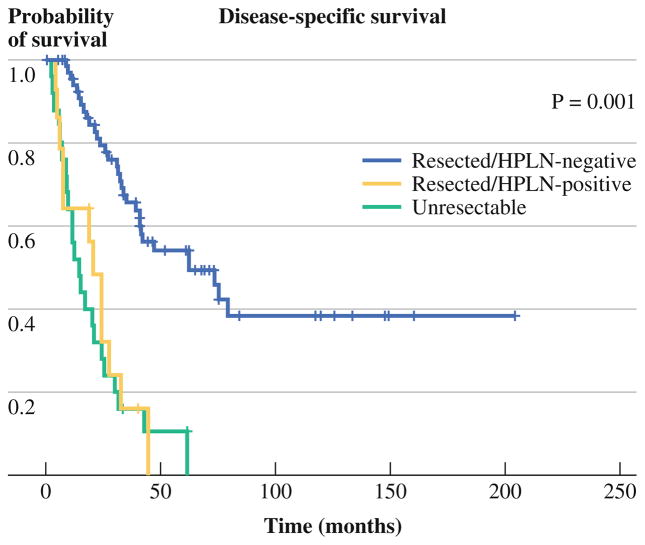

Patients who did not undergo complete gross resection as a result of intraoperative findings of sub-radiographic distant metastatic disease or locally unresectable disease had a median DSS of 14.7 months (95 % CI 9.1–25.4) compared to 20.5 months (95 % CI 6.1–27.5) for those who had complete gross resection with a positive HPLN, and 62.4 months (95 % CI 40.7—NR) for those who had complete gross resection with a negative HPLN (p < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Kaplan–Meier DSS estimates for all patients stratified by HPLN status and resectability. Patients who underwent complete gross resection with a positive HPLN shared the same survival outcome as patients with grossly unresectable disease

DISCUSSION

The optimal method of lymph node staging and the clinical significance of lymph node metastases in biliary tract adenocarcinoma are controversial. Historically, lymph node staging has been based on location of involved nodes. More recent studies have evaluated total lymph node count and lymph node ratio as methods of assessment of nodal status. Aoba et al.9 reported a series of 146 patients with lymph node metastases from perihilar cholangiocarcinoma and found that the number of involved lymph nodes, but not the location of nodes, was an independent prognostic factor. Similarly, another retrospective study of patients with biliary tract cancer (including ampullary cancers) found that number of metastatic lymph nodes was prognostic and concluded that patients with no more than one node involved may achieve long-term survival after curative resection.10 These are small series, however, and contradict prior reports demonstrating the importance of location of involved nodes.2,11,12 Additionally, accurate determination of total lymph node count and lymph node ratio rely on standardized pathologic assessment of specimens, which is difficult to control for across institutions.

The current AJCC and Japanese Society of Biliary Surgery staging systems classify nodal metastases on the basis of location of involved lymph nodes with distant nodes (beyond the porta hepatis) constituting N2 or M1 disease.1 Although any lymph node involvement is a poor prognostic factor in biliary tract cancer, patients with disease limited to regional (N1) nodes can achieve long-term survival after resection.13 Long-term survival is not typically achieved in patients with metastases to more distant nodes (N2 and beyond). There is currently no standardized method for intraoperative assessment of nodal disease burden. Many patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma undergo resection with no lymphadenectomy.14,15 At the other extreme, extended lymphadenectomy of para-aortic nodes has been recommended for patients with gallbladder cancer in the Japanese literature.13,16,17 This practice may lead to increased perioperative morbidity, however, and may not provide benefit.

The technique of nodal staging by sampling of the HPLN requires no additional dissection than what is routinely performed for exposure of the portal vein and portal structures. The rate of HPLN positivity in this series was 30 % and HPLN positivity was associated with the intraoperative finding of sub-radiologic, unresectable disease. For patients who did go on to have complete gross resection (R0/R1), HPLN positivity was highly prognostic of recurrence and survival. Although we know that some patients with local LN involvement are able to achieve long-term survival, patients with positive HPLN who underwent complete gross resection of their disease in this cohort shared the same survival outcome as patients with unresectable disease. All HPLN-positive patients who underwent complete gross resection experienced recurrence or death from disease within 4 years of surgery.

This study is limited in its retrospective design. There may be an uncharacterized selection bias in those patients who underwent HPLN sampling which was the inclusion criterion for the study. Additionally, although all patients had HPLN sampling, not all patients underwent sampling of local (N1) lymph nodes or of additional N2 nodes to determine correlations between HPLN positivity and the presence of metastases in other nodal basins. Regardless, the prognostic value of the HPLN in this series was striking and this technique of intraoperative nodal staging warrants further investigation in a prospective study. The current data suggest that this simple technique may be able to identify patients with biliary tract malignancy who may not benefit from standard surgical resection. If these findings are validated, efforts could be made to sample this node endoscopically to identify these patients pre-operatively. These patients should be considered for up front systemic therapy or resection with more aggressive lymphadenectomy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1245/s10434-013-3352-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.Edge SB, Rusch VW, Coit DG, et al., editors. AJCC cancer staging manual. 7. New York: Springer; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng H, Wang X, Fong Y, Wang ZH, Wang Y, Zhang ZT. Outcomes of radical surgery for gallbladder cancer patients with lymphatic metastases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2011;41:992–8. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyr072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shirai Y, Sakata J, Wakai T, Ohashi T, Ajioka Y, Hatakeyama K. Assessment of lymph node status in gallbladder cancer: location, number, or ratio of positive nodes. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:87. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-10-87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ito M, Mishima Y, Sato T. An anatomical study of the lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder. Surg Radiol Anat. 1991;13:89–104. doi: 10.1007/BF01623880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirai Y, Yoshida K, Tsukada K, Ohtani T, Muto T. Identification of the regional lymphatic system of the gallbladder by vital staining. Br J Surg. 1992;79:659–62. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Uesaka K, Yasui K, Morimoto T, et al. Visualization of routes of lymphatic drainage of the gallbladder with a carbon particle suspension. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:345–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Clavien PA, Georgiev P, Fong Y, Sarr MG. Atlas of upper gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery. Berlin: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ito K, Ito H, Allen PJ, et al. Adequate lymph node assessment for extrahepatic bile duct adenocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2010;251:675–81. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181d3d2b2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aoba T, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, et al. Assessment of nodal status for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: location, number, or ratio of involved nodes. Ann Surg. 2013;257:718–25. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182822277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi S, Nagano H, Marubashi S, et al. Clinicopathological features of long-term survivors for advanced biliary tract cancer and impact of the number of lymph nodes involved. Int J Surg. 2013;11:145–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2012.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donohue JH, Stewart AK, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on carcinoma of the gallbladder, 1989–1995. Cancer. 1998;83:2618–28. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981215)83:12<2618::aid-cncr29>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jarnagin WR, Fong Y, DeMatteo RP, et al. Staging, resectability, and outcome in 225 patients with hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg. 2001;234:507–17. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200110000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shirai Y, Wakai T, Sakata J, Hatakeyama K. Regional lymphadenectomy for gallbladder cancer: rational extent, technical details, and patient outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:2775–83. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i22.2775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg. 2007;245:755–62. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251366.62632.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Clark CJ, Wood-Wentz CM, Reid-Lombardo KM, Kendrick ML, Huebner M, Que FG. Lymphadenectomy in the staging and treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a population-based study using the National Cancer Institute SEER database. HPB (Oxford) 2011;13:612–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shimada H, Endo I, Togo S, Nakano A, Izumi T, Nakagawara G. The role of lymph node dissection in the treatment of gallbladder carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:892–9. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19970301)79:5<892::aid-cncr4>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shirai Y, Ohtani T, Tsukada K, Hatakeyama K. Combined pancreaticoduodenectomy and hepatectomy for patients with locally advanced gallbladder carcinoma: long term results. Cancer. 1997;80:1904–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.