Abstract

Demand for human primary hepatocytes is increasing, particularly for clinical trials of hepatocyte transplantation. However, due to the severe shortage of organ transplant donors, the source of cells for these endeavors is restricted to untransplantable livers, such as those from non-heart-beating donors and surgically resected liver tissues. To improve cell recovery from such sources after warm ischemia, we evaluated the efficacy of applying perfusion solutions, focusing on improvement of hepatocyte recovery. Warm ischemia was induced by clamping both portal vein and hepatic artery for 10 or 15 min in rats. The liver was perfused with either Euro-Collins (EC) or extracellular-type trehalose-containing Kyoto (ETK) solutions supplemented with an anticoagulant, either heparin or citrate phosphate dextrose solution (CPD), compared to Ca2+, Mg2+-free Hanks solution. While the viability of recovered cells was 81.5 ± 4.2% and cell yield was 2.27 ± 0.53 × 108 in nonwarm ischemia controls (n = 11), these values were only 74.7 ± 2.9% and 0.38 ± 0.17 × 108, respectively, in the 10-min warm ischemia group, using the Hanks as the perfusion solution. Although the addition of heparin increased the live cell number only twofold (0.71 ± 0.40 × 108, n = 4), the best improvement was achieved by adding CPD to EC. This resulted in a recovery of 1.41 ± 0.50 × 108 in the 10-min ischemia group (n = 7) and 1.37 ± 0.28 × 108 in the 15-min group (n = 3). Macroscopic observation showed that blood had been completely flushed out by the solution, suggesting good restoration of the microcirculation in ischemic liver. Using ETK instead of EC resulted in a slight decrease in efficacy. These results demonstrate that CPD, as opposed to heparin, is effective in ensuring liver microcirculation and flushing out the blood and that EC is the best perfusion solution for obtaining hepatocytes from ischemic liver.

Keywords: Hepatocyte isolation, Warm ischemia, Citrate

INTRODUCTION

A number of studies using human primary hepatocytes have been published in the field of pharmaceutical drug discovery, cell biology, and regenerative medicine (3,7,10,11); however, there are three major difficulties in the pursuit of this research: obtaining long-term culture, storage, and procurement. The latter is an especially serious issue affecting all research activities. Hepatocytes are sometimes obtained from surgically resected tissue, which is generally not ideal due to size limitations, possible contamination with pathological tissues such as tumor cells, and the warm ischemic time. Another source of hepatocytes is via deceased donors. However, because organ transplantation has the first priority, cadaveric hepatocyte donors usually have deficits that precluded transplantation, including perhaps a prolonged warm ischemic episode, as what frequently occurs with non-heart-beating donors.

Warm ischemia is the most serious factor impairing the viability of organ and tissues and is usually attributed to an irreparable decrease in ATP, cellular edema due to ion channel inactivation, and the onset of coagulation (2,4,5,9). The last issue encompasses the breakdown of the vascular network. To isolate live hepatocytes, intercellular connective tissue is digested by perfusing collagenase through existing blood vessels. Therefore, vascular integrity affects the recovery and quality of the isolated cells. Indeed, cell recovery from surgically resected liver tissue that has suffered from long-term warm ischemia is poor. The number of undigested hepatic lobules is increased in such cases. We postulated that cell recovery would be improved by the flushing out of the blood and restoration of the microcirculation. Here, by evaluating the number of isolated liver hepatocytes as an indicator, we estimate the efficacy of perfusion with different organ preservation solutions supplemented with anticoagulants.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Nine-week-old Sprague–Dawley (SD) rats (specific pathogen free) were purchased from Sankyo Labo Service Co., Inc. (Tokyo, Japan). The animals were given chow and water ad libitum.

Perfusion and Collagenase Solution

Euro-Collins (EC) and extracellular-type trehalose-containing Kyoto (ETK) solutions were purchased from I’rom Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) and Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan), respectively. EC was supplemented with glucose to a final concentration of 3.5% before use as indicated in the manufacturer’s instructions. Anticoagulant citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD) solution was prepared by dissolving 26.3 g trisodium citrate dihydrate, 2.99 g citrate acid, 23.2 g D(+)-glucose, and 2.51 g sodium dihydrogenphosphate in 1 L extra-pure water. All chemicals were of the highest grade from Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd. (Osaka, Japan).

Calcium- and magnesium-free Hanks solution (CM-free Hanks) was prepared by dissolving one bottle of Hank’s balanced salts mixture for 1 L (H2387, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc., St. Louis, MO, USA) and adding 0.19 g ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA; E4378-100G, Sigma-Aldrich, Inc.) and 23.8 g 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES; 17546-34, Nacalai Tesque, Inc., Kyoto, Japan) in extra-pure water. The pH was adjusted to 7.2 with 10 mol/L NaOH. The solution for use with collagenase was prepared as above, except that EGTA was replaced by 0.56 g CaCl2 (Wako Pure Chemicals) and the pH was adjusted to 7.5. All prepared solutions were sterilized by filtration through a 0.22-µm pore membrane (8030-001, Asahi Glass Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and stored at room temperature until use.

Collagenase (032-10534 Wako Pure Chemicals) was dissolved in saline at a concentration of 100 mg/ml as a stock solution, aliquoted, and stored at −30°C until use. One hour before use, 1 ml of collagenase stock solution was diluted in 100 ml of the Hanks-CaCl2 solution.

Liver Warm Ischemia Treatment

Animals were divided into three groups with a warm ischemic time (WIT) of 0 min (control), 10 min, or 15 min. Under inhalation anesthesia with 3.5% enflurane (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA) and the rat in a supine position, an incision was made along the median line of the abdomen to expose the portal vein. A catheter (22 G, SR-FF2232, Terumo Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the portal vein at a site proximal to the liver, and a 3–0 suture was placed beneath the vein ready to ligate. Both portal vein and hepatic artery were then clamped to block blood flow for the determined time. Experimental conditions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Experimental Conditions

| Group | WIT a (min) | Solution for Perfusion b | Sample No. (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | CM-free Hanks | 11 |

| 2 | 10 | CM-free Hanks | 3 |

| 3 | 10 | CM-free Hanks + heparin | 4 |

| 4 | 10 | CM-free Hanks + CPD | 3 |

| 5 | 10 | EC + heparin | 5 |

| 6 | 10 | EC + CPD | 7 |

| 7 | 10 | ETK + CPD | 4 |

| 8 | 15 | EC + heparin | 3 |

| 9 | 15 | EC + CPD | 3 |

| 10 | 15 | ETK + heparin | 3 |

| 11 | 15 | ETK + CPD | 3 |

WIT, warm ischemic time.

CM-free Hanks, Ca2+, Mg2+-free Hanks; EC, Euro-Collins; ETK, extracellular-type trehalose-containing Kyoto; CPD, citrate phosphate dextran solution.

Perfusion and Hepatocyte Isolation

After ischemic treatment, the liver was perfused to remove blood through the portal catheter at a pressure of 60 cm H2O with 100 ml of CM-free Hanks, EC, or ETK, with or without anticoagulant, that is, 14% CPD or 2 U/ml heparin as indicated. Hepatocyte isolation was performed according to the method of Seglen (8). Briefly, 100 ml of warm (38°C) collagenase solution was perfused through the liver for 10 min. The whole liver was then carefully removed, placed in a 200-ml sterilized beaker with 50 ml of Dulbecco’s modified minimum essential medium (041-29775, Wako Pure Chemicals). The liver was gently teased apart using a Pasteur pipette (IK-PAS-9P, Asahi Glass Co., Ltd.), and the cell suspension thus obtained was sequentially filtered through sterilized gauze (071116A, Suzuran Sanitary Goods Co., Ltd., Nagoya, Japan) and 100-µm nylon mesh (SN-91-1194, SANSYO Co., Ltd, Tokyo, Japan). Viability and total number of parenchymal hepatocytes were assessed in a hemocytometer (C-Chip NI DHC-N01, Digital Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) with 0.04% trypan blue (15250-061 Gibco, Life Technologies Ltd., Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Data Presentation and Statistics

All data are given as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance followed by unpaired Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical Considerations

All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee (Reference No. 2010-005).

RESULTS

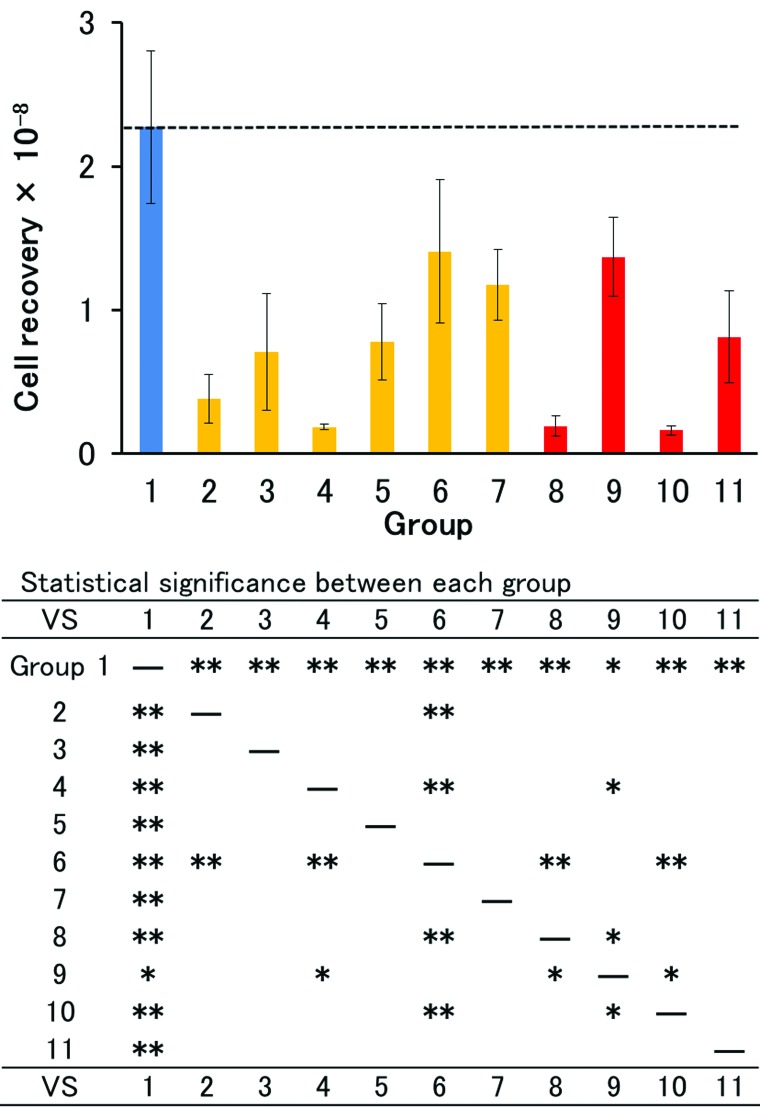

Hepatocyte Recovery From Ischemic Liver

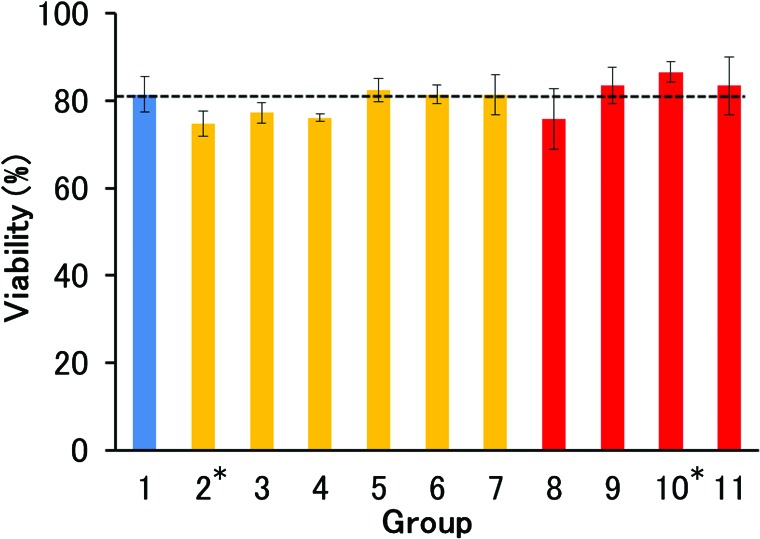

Rat hepatocytes were isolated from nonischemic liver using CM-free Hanks with a recovery of 2.27 ± 0.53 × 108 live hepatic parenchymal cells and a viability of 81.5 ± 4.2% (n = 11) (Group 1 in Figs. 1 and 2, also indicated by horizontal dashed line). After 10-min ischemia, cell recovery decreased to 0.38 ± 0.17 × 108, corresponding to 16.7% of the nonischemic control (Group 2). Perfusing the liver with CM-free Hanks containing heparin resulted in a doubling of the recovery (Group 3), whereas the addition of CPD had an adverse effect (Group 4). However, when we used EC instead of Hanks, the addition of CPD markedly increased cell recovery to 1.41 ± 0.50 × 108 cells (62.1% of the nonischemic control) (Group 6), while the effect of heparin was approximately half that of CPD (Group 5). ETK containing CPD was slightly less effective than EC containing CPD (Group 7). After 15-min ischemia, the superiority of EC containing CPD was even more marked (Groups 8 to 11). Perfusion with EC containing CPD resulted in a recovery (1.37 ± 0.28 × 108 cells) as high as that after 10-min ischemia. Again, ETK was less effective than EC, and the addition of heparin instead of CPD did not improve cell recovery with either EC or ETK. There was no marked difference in viability, but the values in Groups 2, 3, and 4 where CM-free Hanks was used as the base solution were low compared with the other groups (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Number of live hepatocytes isolated from warm ischemic livers. Horizontal dashed line indicates the level of control (Group 1). Details of experimental condition (Groups 1 to 11) are described in the text and Table 1. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction and is shown below the graph (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

Figure 2.

Viability of hepatocytes isolated from warm ischemic livers. Horizontal dashed line indicates the level of control (Group 1). Details of experimental condition (Groups 1 to 11) are described in the text and Table 1. Statistical significance was determined by unpaired Student’s t test with Bonferroni correction. The only significant difference was between Groups 2 and 10 (*p < 0.05).

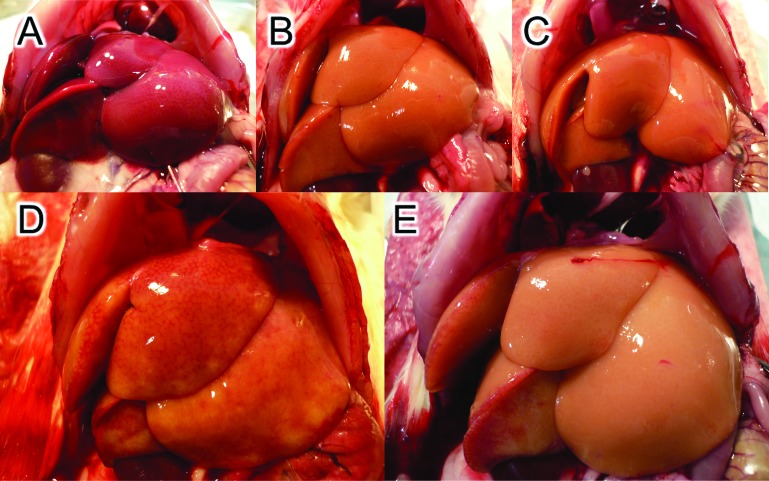

Macroscopic Observation of Ischemic Liver After Perfusion

Only a few minutes after clamping the portal vein and hepatic artery, the color of the liver changed to and remained a dull red (Fig. 3A). Perfusion with ETK containing either heparin or CPD flushed out the blood equally well (Fig. 3B, C), but the cell recovery was different as shown in Groups 10 and 11 of Figure 1. On the other hand, the appearance of the liver differed according to the added anticoagulant in the EC perfusion group. Liver perfused with EC containing CPD looked obviously clearer than after perfusion with EC containing heparin (Fig. 3D, E). In the latter case, a number of small blood spots were visible, suggesting the formation of microthrombi.

Figure 3.

Macroscopic appearance of ischemic liver and the liver after perfusion. Livers were treated with warm ischemia for 15 min (A)and then perfused with extracellular-type trehalose-containing Kyoto (ETK) containing heparin (Group 10) (B), ETK containing CPD (Group 11) (C), Euro-Collins (EC) containing heparin (Group 8) (D), and EC containing citrate phosphate dextrose (CPD) (Group 9) (E). There was no marked difference between (B) and (C), although the live hepatocyte recovery was different (Groups 10 and 11 in Table 1). Marked differences in blood retention were observed between (D) and (E), reflected in the cell recovery (Groups 8 and 9 in Table 1).

DISCUSSION

Biological homeostasis depends on the blood supply, so the cessation of circulation induces severe damage to organs and tissues, meaning that long-term ischemia is a major contraindication for organ transplantation. However, due to the severe shortage of organ donors, non-heart-beating donors are considered as expanded criteria donors. Although some of the latter are not suitable for transplantation, it may still be possible to isolate hepatocytes from them. Thus, one promising application of an untransplantable liver and surgically resected tissues is as a source of hepatocytes for cell transplantation and research in drug discovery.

One technical breakthrough in hepatocyte isolation was the introduction of collagenase perfusion procedures via the hepatic portal vein route (8). This greatly improved cell viability and recovery compared to nonperfusion methods that are dependent on incubating chopped-up liver tissue with proteases. However, successful isolation by perfusion is dependent on the integrity of the microvascular structure with the most important factor being the thorough flushing out of the blood. The most common perfusate for this purpose is CM-free Hanks containing EGTA, a chelating agent. However, this solution was not particularly effective in the experiments reported here. The addition of heparin to the solution slightly improved results, whereas CPD did not. The decreased recovery when using CPD-supplemented CM-free Hanks was likely due to the acidity of the solution.

In the present study, the optimal solution for perfusing ischemic liver was EC containing CPD. EC is a well-known organ preservation solution with a composition of 10 mmol/L Na and 115 mmol/L K ions similar to the intracellular milieu, while ETK duplicates extracellular Na and K concentrations (6,12). Additionally, EC contains glucose and ETK trehalose as a sugar constituent. Regarding the use of anticoagulant, CPD seems to be more effective in restoring circulation judging from live cell recovery and macroscopic observation. CPD is used routinely as an anticoagulant in blood transfusion. Its mechanism of action is chelation, inhibiting the onset of calcium-dependent coagulation. On the other hand, heparin, a widely used anticoagulant, is not a chelating agent, but an augmenter of antithrombin III, the inactivator of thrombin. Heparin is a biosynthetic polysaccharide with an affinity for various bioactive macromolecules. Thus, heparin is not a simple anticoagulant but has multivalent bioreactivity. Indeed, heparin carries a potential risk of inducing thrombosis known as heparin-induced thrombosis or HIT (1). The uncertainty of the heparin effect on hepatocyte recovery is most likely attributable to the above characteristics.

In this investigation, we demonstrated the usefulness of EC containing CPD for liver pretreatment prior to hepatocyte isolation. This property may be applied to the preconditioning of expanded criteria donor organs for transplantation in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Dr. Ryo Tanaka for his heartfelt encouragement. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid from the Japanese Health Science Foundation (KHD1023) and National Center for Child Health and Development. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Cuker A. Recent advances in heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 18:315–322; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ejiri S.; Eguchi Y.; Kishida A.; Kurumi Y.; Tani T.; Kodama M. Protective effect of OPC-6535, a superoxide anion production inhibitor, on liver grafts subjected to warm ischemia during porcine liver transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 32:318–321; 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Enosawa S.; Miyamoto Y.; Hirano A.; Suzuki S.; Kato N.; Yamada Y. Application of cell array 3D-culture system for cryopreserved human hepatocytes with low attaching capability. Drug Metab. Rev. 39(Suppl1):342; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hisanaga M.; Nakajima Y.; Wada T.; Kanehiro H.; Fukuoka T.; Horikawa M.; Yoshimura A.; Kido K.; Taki J.; Aomatsu Y.; Ueno M.; Ko S.; Nakano H. Protective effect of the calcium channel blocker diltiazem on hepatic function following warm ischemia. J. Surg. Res. 55:404–410; 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kamiike W.; Burdelski M.; Steinhoff G.; Ringe B.; Lauchart W.; Pichlmayr R. Adenine nucleotide metabolism and its relation to organ viability in human liver transplantation. Transplantation 45:138–143; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mühlbacher F.; Langer F.; Mittermayer C. Preservation solutions for transplantation. Transplant. Proc. 31:2069–2070; 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sahi J.; Grepper S.; Smith C. Hepatocytes as a tool in drug metabolism, transport and safety evaluations in drug discovery. Curr. Drug Discov. Technol. 7:188–198; 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Seglen P. O. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 13:29–83; 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Spector D.; Limas C.; Frost J. L.; Zachary J. B.; Sterioff S.; Williams G. M.; Rolley R. T.; Sadler J. H. Perfusion nephropathy in human transplants. N. Engl. J. Med. 295:1217–1221; 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun L. Y.; Lin S. Z.; Li Y. S.; Harn H. J.; Chiou T. W. Functional cells cultured on microcarriers for use in regenerative medicine research. Cell Transplant. 20:49–62; 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tanaka K.; Soto-Gutierrez A.; Navarro-Alvarez N.; Rivas-Carrillo J. D.; Jun H. S.; Kobayashi N. Functional hepatocyte culture and its application to cell therapies. Cell Transplant. 15:855–864; 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoshida H.; Okuno H.; Kamoto T.; Habuchi T.; Toda Y.; Hasegawa S.; Nakamura T.; Wada H.; Ogawa O.; Yamamoto S. Comparison of the effectiveness of ET-Kyoto with Euro-Collins and University of Wisconsin solutions in cold renal storage. Transplantation 74:1231–1236; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]