Abstract

Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) may influence the growth and metastasis of various human malignancies, including hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Therefore, the underlying mechanisms via which MSCs are able to affect malignancies require investigation. In the present study, the potential role of MSC in the angiogenesis of HCC was investigated. A total of 17 nude mouse models exhibiting human HCC were used to evaluate the effects of MSC on angiogenesis. A total of 8 mice were injected with human MSCs via the tail vein, and the remaining 9 mice were injected with phosphate-buffered saline as a control. A total of 35 days subsequent to the injection of MSCs, the microvessel density (MVD) of tumors was evaluated by immunostaining, using cluster of differentiation 31 antibody. The mRNA levels of transforming growth factor (TGF)β1, Smad2 and Smad7 were detected using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Protein expression levels of TGFβ1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in tumor tissues were analyzed using ELISA. Compared with controls, MVD in MSC-treated mice was significantly increased (28.00±9.19 vs. 18.11±3.30; P=0.006). The levels of TGFβ1 mRNA in the MSC-treated group were 2.15-fold higher compared with the control group (1.27±0.61 vs. 0.59±0.39; P=0.033), and MVD was higher in the group exhibiting increased TGFβ1 mRNA levels compared with the control group (26.50±9.11 vs. 19.44±6.14; P=0.038). In addition, a close correlation between the expression levels of TGFβ1 and VEGF was identified. The results of the present study suggested that MSCs may be capable of enhancing the angiogenesis of HCC, which may be partly due to the involvement of TGFβ1.

Keywords: hepatocellular carcinoma, mesenchymal stem cell, angiogenesis, transforming growth factor, vascular endothelial growth factor, microvessel density

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-associated mortality worldwide (1,2). The poor prognosis of HCC is primarily due to the high rate of tumor recurrence following surgery, or the occurrence of intrahepatic metastasis (3,4). Accumulating evidence indicates that the occurrence of liver disease may be strongly associated with bone marrow cells (5–7). Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs) have an inhibitory role in HCC metastasis (8).

Angiogenesis is a process that leads to the formation of novel blood vessels from preexisting vascular networks. Angiogenesis is a necessary process for tumor growth, invasion and metastasis (9). Intratumor microvessel density (MVD) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are significant biomarkers for the assessment of angiogenesis (10). Due to the hypervascular nature of HCC tumors, angiogenesis has a significant role in the progression of HCC (11). VEGF and MVD have been demonstrated to be potential predictors for clinical outcomes and HCC metastatic recurrence (12).

It has been reported that BM-MSCs may contribute to tumor vascularization (13). BM-MSCs are a progenitor for angioblasts, which subsequently differentiate into cells that express endothelial markers, which are capable of functioning in vitro as mature endothelial cells, as well as contributing to neoangiogenesis in vivo (14). MSCs are additionally capable of releasing various cytokines, including VEGF and transforming growth factor (TGF)β1 (8,15). These cytokines are able to influence angiogenesis in tumors (16–18). However, the potential role of MSCs in the angiogenesis of HCC tumors remains to be elucidated.

In a previous study conducted by the authors of the present study, it was identified that MSCs are able to home to the sites of HCC tumors, and affect tumor growth and progression via the action of TGFβ1 (8). However, the role of MSCs in the angiogenesis of HCC tumors remains to be elucidated. Therefore, in the present study, the aim was to investigate the potential role of MSCs in the angiogenesis of HCC tumors.

Materials and methods

Cell lines

Human BM-derived MSCs were purchased from Sciencell Research Laboratories (Carlsbad, CA, USA). These cells were isolated from human bone marrow, and characterized by immunofluorescent methods, using cluster of differentiation (CD)44 and CD90 antibodies and lipid staining following differentiation. Following 5 passages of subculture, the cells were re-evaluated by immunocytochemical staining in order to assure that the normal phenotype of MSCs had been retained. The 5th passage MSCs did not express the surface marker CD34, expressed low levels of fetal liver kinase (Flk)-1 and increased levels of CD29 and CD105. Reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) revealed that the MSCs expressed octamer-binding transcription factor-4 and Flk-1, which was concordant with previously published data concerning MSC cell surface markers (19). Cells were cultured in α-modified minimum essential medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin solution (Sciencell Research Laboratories). The medium was replaced when the cell density reached 5,000 cells/cm2 and the culture reached 50% confluence. Cells were subcultured when 90% confluence was reached. Cells that had undergone between 5 and 8 passages were utilized for the following experiments.

MHCC97-H human HCC cell line was purchased from the Liver Cancer Institute of Fudan University (Shanghai, China). These cells exhibit a high metastatic potential, are positive for α-fetoprotein, albumin and cytokeratin 8 expression, and negative for hepatitis B (HBV) surface antigen. Fluorescence PCR has revealed the occurrence of HBV DNA integration in the cellular genome (20,21). The cells were cultured in high glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco; Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C in a humidified incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2.

Animal models

In total, 8 female mice and 9 male mice were randomly assigned into two groups, an experimental group and a control group. All mice were fed under specific-pathogen free conditions, food and water were treated by high pressure steam sterilization, and the feeding temperature was 28°C. A total of 6×106 MHCC97-H cells were subcutaneously implanted into nude mice. A total of 30 days subsequent to implantation, subcutaneous tumor tissue was removed and cut into 1×1×1 mm3 tissue sections. These sections were subsequently orthotopically implanted into the livers of 17 nude mice.

The experiments were performed following the approval of Xijing Medical Ethics Committee (Xi'an, China), and were also in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and Animal Research: Reporting in vivo experiments guidelines (22).

MSC injection

In order to evaluate the potential effects of MSCs on pulmonary metastasis of HCC, 8 of the mice were treated with 5×105 human MSCs via tail vein injection 3 times in one week. The remaining 9 mice were treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.2 ml), 3 times a week, as a control. A total of 35 days following injection, the mice were sacrificed and tumors were removed, weighed and subsequently cryopreserved at −80°C, with a 1:4 dilution of optimal cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Inc., Torrance, CA, USA) in PBS. Liver and lung tissues were fixed in paraformalin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) and embedded in paraffin.

Evaluation of lung metastasis of HCC

The incidence and tumor foci number of the lung metastases were evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Inc., Shanghai, China) staining in 10 consecutive sections, with an interval of 50 µm, and were additionally assessed by two independent pathologists.

MVD counting

Fresh-frozen 8-µm sections of tumor were fixed in acetone sections (Spectrum Chemical Manufacturing Corporation, New Brunswick, NJ, USA), and stained using monoclonal mouse anti-CD31 (CBL1337; dilution, 1:200; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA); and subsequently donkey anti-mouse Immunoglobulin G-horseradish peroxidase (AP189; dilution, 1:500; EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA) was used as a secondary antibody. Following 3,3-diaminobenzidine (ZSGB-BIO, Beijing, China) staining, the maximum density of positive staining was selected as microscope field (magnification, ×20) and microvessels were counted.

RNA extraction and RT-qPCR

Total RNA of tumor tissues was extracted using TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. SYBR Green Realtime PCR Master Mix (Toyobo Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan) was used to perform RT-qPCR analysis, in order to identify the expression levels of TGFβ1, Smad2 and Smad7. The primers were designed using Primer Premier software version 5.0 (PREMIER Biosoft, Palo Alto, CA, USA), and the sequences used are listed in Table I. Amplification conditions were as follows: 95°C for 9 min, followed by 45 cycles at 95°C for 30 sec, 57°C for 30 sec and 72°C for 15 sec, followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. β-actin served as a control for detection of the presence of amplifiable complementary DNA. The mRNA expression levels were quantified using the 2−∆∆Cq method. In brief, the Cq value for the target gene was subtracted from the Cq value of β-actin in order to give a ∆Cq value. The average ∆Cq value was calculated for the control group, and this value was subsequently subtracted from the ∆Cq value of all other samples (including the control group). This resulted in the production of a ∆∆Cq value for all samples, which was subsequently used in order to calculate the fold-induction of mRNA expression of the target genes using the formula 2−∆∆Cq, as recommended by the manufacturer's protocols (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc., Hercules, CA, USA). In the present study, MHCC97-H model samples served as the control group.

Table I.

Primer sequences used for reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction.

| Gene | Primer | Sequence 5′→3′ |

|---|---|---|

| TGFβ1 | Sense | 5′-GGCGATACCTCAGCAACCG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CTAAGGCGAAAGCCCTCAAT-3′ | |

| Smad2 | Sense | 5′-TACTACTCTTTCCCCTGT-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-TTCTTGTCATTTCTACCG-3′ | |

| Smad7 | Sense | 5′-CAACCGCAGCAGTTACCC-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-CGAAAGCCTTGATGGAGA-3′ | |

| β-actin | Sense | 5′-TCGTGCGTGACATTAAGGAG-3′ |

| Antisense | 5′-ATGCCAGGGTACATGGTAAT-3′ |

TGF, transforming growth factor.

Protein extraction and ELISA

Tumor samples were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 150 mM NaCl; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 1% NP-40; 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate) plus serine protease inhibitors. Protein was extracted by microcentrifugation for 30 min at 13,000 × g. Protein concentration was determined using Bradford Reagent (Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology, Inc.). The VEGF and TGFβ1 concentration in the protein extracts was determined using the Human VEGF Quantikine ELISA assay kit (DVE00; R&D Systems, Inc., Minneapolis, MN, USA) and Human TGF-beta 1 Quantikine ELISA kit (R&D Systems, Inc.)according to the manufacturer's protocol. The optical density values were measured using a Spectramax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, LLC., Sunnyvale, CA, USA) at 450 nm wavelength.

Statistical analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS version 11.5 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Student's t test was utilized for analysis of the significance of differences between tumor weight and volume, and mRNA expression levels of target genes for independent samples. Fishers' exact test was performed for the comparison of ratio involved. All statistical tests performed were two-sided, and P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

MSC treatment reduces the rate of pulmonary metastasis of HCC

No difference in tumor weight was observed between the group treated with MSCs and the untreated control group; the ratios of tumor to body weight were 0.14±0.05 vs. 0.13±0.04, respectively (P=0.75). Compared with the control group, the pulmonary metastasis rate of the MSC-treated mice (100 vs. 50%, for the control and MSC-treated mice, respectively) was statistically reduced (100%; P=0.029; Table II).

Table II.

Inhibitory effects of MSC on the in vivo pulmonary metastasis of hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | MSC injection | No MSC injection | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals | 8 | 9 | N/A |

| Body weight, g | 21.99±2.90a | 22.08±1.69a | 0.918 |

| Tumor weight, g | 2.90±0.80a | 2.86±0.72a | 0.906 |

| Tumor weight/body weight, g | 0.14±0.05a | 0.13±0.04a | 0.754 |

| Lung metastasis, % | 50% | 100% | 0.029 |

| No. of lung metastases | 1.37±1.60a | 1.77±0.97a | 0.263 |

| Cellular no. of metastases | 50.37±60.19a | 74.44±84.22a | 0.292 |

Student's t test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences in tumor weight, number of lung metastases and cellular numbers of metastases between the MSC injection group and no MSC injection group. Lung metastatic rate was evaluated using Fishers' exact test.

mean ± standard deviation. MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; N/A, not applicable.

MSC treatment exerts differential effects on the expression of mRNA of TGFβ1 and Smads in HCC tumors

Levels of TGFβ1 mRNA in the MSC-treated group were 2.15-fold higher compared with the untreated controls (1.27±0.61 vs. 0.59±0.39; P=0.033), however, the levels of Smad7 mRNA were downregulated compared with untreated controls (0.76±0.29 vs. 1.41±0.50; P=0.006; Table III).

Table III.

Expression of TGFβ1, Smads and VEGF were influenced by MSC injection in mouse models.

| Variable | MSC, mean ± SD | No MSC, mean ± SD | Fold change | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TGFβ1 mRNA | 1.27±0.61 | 0.59±0.39 | +2.15 | 0.033 |

| Smad2 mRNA | 1.01±0.14 | 1.25±0.38 | −1.25 | 0.114 |

| Smad7 mRNA | 0.76±0.29 | 1.41±0.50 | −1.86 | 0.006 |

| TGFβ1 protein | 0.02±0.01 | 0.03±0.01 | −1.50 | 0.267 |

| VEGF protein | 0.29±0.05 | 0.31±0.13 | −1.07 | 0.631 |

| Microvessel density | 28.00±9.19 | 18.11±3.30 | +1.55 | 0.006 |

Student's t test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences between the MSC injection group and no MSC injection group. SD, standard deviation; TGF, transforming growth factor; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; ‘+’ denotes a fold increase, ‘-’ denotes a fold decrease.

MSC treatment exerts differential effects on MVD and VEGF expression in HCC

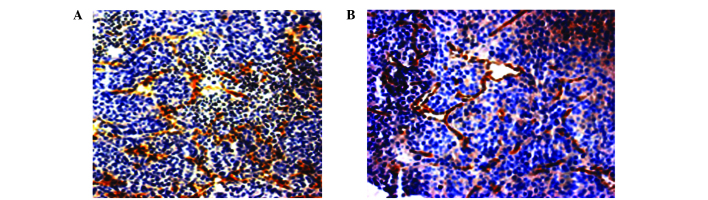

The expression of VEGF in the MSC-treated group did not significantly differ compared with the untreated control group (0.29±0.05 vs. 0.31±0.13; P=0.631). However, MVD was significantly increased in the MSC-treated group compared with the untreated control group (28.00±9.19 vs. 18.11±3.30; P=0.006; Fig. 1; Table III).

Figure 1.

Comparison of MVD between the MSC injection and no MSC injection groups. (A) MVD of tumor tissues in the MSC injection group was visualized by immunohistochemical staining, using cluster of differentiation 31 antibody. The sample was observed under a light microscope (magnification, ×20). Brown coloring indicated microvessel positivity. (B) MVD in the group without MSC injection. MVD, microvessel density; MSC, mesenchymal stem cells.

Levels of TGFβ1 mRNA are associated with MVD

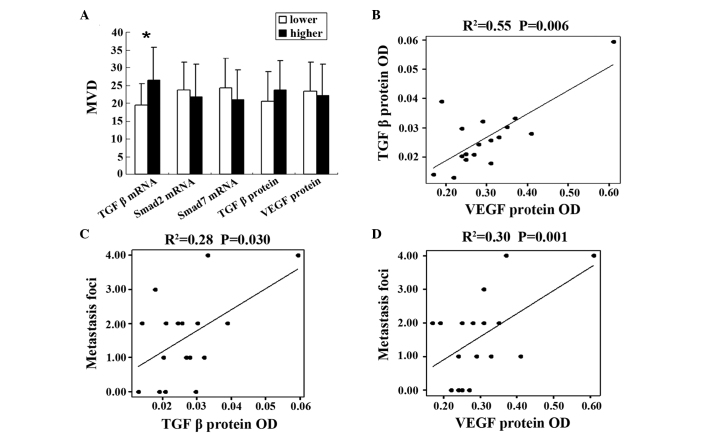

According to the median levels of TGFβ1 mRNA, Smad2 mRNA, Smad7 mRNA, TGFβ1 protein and VEGF protein, expression levels were divided into two groups, high-level and low-level. MVD was increased in the TGFβ1 mRNA high-level group compared with the low-level group (26.50±9.11 vs. 19.44±6.14; P=0.038), however, the levels of Smad2 mRNA (23.67±7.84 vs. 21.75±9.14; P=0.648), Smad7 mRNA (24.33±8.26 vs. 21.00±8.46; P=0.424), VEGF protein levels (22.12±8.82 vs. 23.33±8.23; P=0.375) and TGFβ1 protein levels (23.66±8.23 vs. 20.63±8.29; P=0.375) demonstrated no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Correlation between MVD and metastasis demonstrated in mouse models. (A) Association between MVD and the expression levels of TGFβ1 mRNA, Smad2 mRNA, Smad7 mRNA, VEGF and TGFβ1 protein. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. *Statistically significant difference between two groups (P<0.05). (B) Correlation between VEGF and TGFβ1 protein. (C) Correlation between TGFβ1 protein and the tumor foci number of pulmonary metastasis. (D) Correlation between VEGF protein and the tumor foci number of pulmonary metastasis. Dots represent all samples, and the line denotes a regression line. MVD, microvessel density; TGF, transforming growth factor; mRNA, messenger RNA; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; OD, optical density.

TGFβ1 and VEGF protein levels are associated with metastasis

In the present study, it was identified that TGF protein levels were closely correlated with VEGF protein levels using linear correlation analysis (R2=0.55; P=0.006; Fig. 2B). In addition, TGFβ1 and VEGF protein levels were observed to be associated with the tumor foci number of metastasis (R2=0.28 and P=0.030; and R2=0.30 and P=0.001, respectively; Fig. 2C and D).

MVD was not observed to be associated with tumor growth and metastasis of HCC

According to the median levels of MVD, samples were divided into two groups, dependent on high or low MVD. No statistically significant differences were identified between the two groups, including for tumor weight, pulmonary metastasis rate, tumor foci number of metastasis and cellular number of metastases (Table IV).

Table IV.

MVD and tumor progression of hepatocellular carcinoma.

| Variable | Low MVD | High MVD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of animals | 8 | 9 | N/A |

| Body weight, g | 20.62±1.66a | 21.58±2.08a | 0.314 |

| Tumor weight, g | 2.87±0.82a | 2.91±0.91a | 0.926 |

| Tumor weight/body weight, g | 0.14±0.05a | 0.14±0.05a | 0.904 |

| Lung metastasis, % | 75.0% | 44.4% | 0.335 |

| No. of lung metastases | 1.75±1.16a | 1.22±1.56a | 0.447 |

| Cellular no. of metastases | 32.38±35.55a | 75.33±97.11a | 0.257 |

Student's t test was used to assess the statistical significance of differences in tumor weight, number of lung metastases and cellular numbers of metastases between the low MVD group and high MVD group. Lung metastatic rate was evaluated by Fishers' exact test.

mean ± standard deviation. MVD, microvessel density; N/A, not applicable.

Discussion

MVD is a direct reflection of tumor angiogenesis, and may be visualized using immunohistochemical staining with antibodies of anti-CD31, anti-CD34, factor VIII and α-smooth muscle actin (23). In the present study, it was identified that MSC is capable of enhancing the MVD of HCC tumors, as well as inhibiting pulmonary metastasis. The results of the present study provided evidence and indicated that MSC may promote tumor angiogenesis and influence tumor progression.

In HCC, MVD is closely associated with tumor size, recurrence and disease-free survival (24). However, the present study did not identify an association between MVD and metastasis and tumor size. Although intratumor MVD is a marker for angiogenesis, it is not able to provide any functional information concerning the underlying molecular pathways involved in the angiogenic activity of a specific tumor (25). Multivariate analysis has indicated that MVD is not an effective prognostic factor when tumor size is >5 cm (9). In addition, three types of intratumor microvessels may be identified in HCC, including capillary-like, sinusoid-like and mixed-type, which make the prognostic value of MVD uncertain (24).

Cytokines have a significant role in tumor metastasis and angiogenesis (26,27). TGFβ1 may influence the invasiveness and metastasis of carcinoma (28–30), and has been observed to particularly promote angiogenesis (31–34). The present study identified that MSCs were able to significantly enhance the expression of TGFβ1 mRNA, however, inhibited the expression of Smad7 mRNA. Additionally, TGFβ1 mRNA expression levels correlated with MVD. The results of the present study suggested that MSCs may promote angiogenesis via the TGFβ1/Smad signaling pathway, and may have revealed a novel mechanism for the role of MSCs in tumor progression. The present study detected TGFβ1 mRNA and protein levels and demonstrated that MVD was correlated with the levels of TGFβ1 mRNA, however, was not correlated with the levels of TGFβ1 protein. This divergence may be due to the complicated post-transcriptional mechanisms involved in translation of mRNA into proteins (35).

No association was identified between MSC injection and VEGF expression, and VEGF was not observed to enhance MVD in the present study. However, a close association was observed between TGFβ1 and VEGF, and these cytokines were demonstrated to be associated with tumor metastasis, which may indirectly reflect the role of VEGF in tumor angiogenesis. It has been reported that VEGF and TGFβ1 interact with each other during the process of angiogenesis. This interaction complicates their role in angiogenesis, and in some cases may induce an inhibitory effect on cancer proliferation (36–39).

In conclusion, the results of the present study suggested that MSCs may enhance the angiogenesis of HCC through the action of TGFβ1. The TGFβ1/Smad signaling pathway and its interaction with VEGF may partly explain the intricate role of MSCs in tumor progression. Whether the increase in angiogenesis is due to the differentiation of MSCs or caused by alternative vascular regulators secreted by MSCs requires investigation in future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr Qiong Xue, Dr Dongmei Gao and Dr Jun Chen in Liver Cancer Institute of Fudan University (Shanghai, China) for their assistance with the animal experiments, Dr Ruixia Sun and Dr Jie Chen in Zhongshan hospital of Fudan University for their suggestions for cell culture, and Dr Haiying Zeng and Dr Tengfang Zhu in the Pathological Department of Zhongshan Hospital of Fudan University, for their assistance with pathological experiments.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.He J, Gu D, Wu X, Reynolds K, Duan X, Yao C, Wang J, Chen CS, Chen J, Wildman RP, et al. Major causes of death among men and women in China. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1124–1134. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ye QH, Qin LX, Forgues M, He P, Kim JW, Peng AC, Simon R, Li Y, Robles AI, Chen Y, et al. Predicting hepatitis B virus-positive metastatic hepatocellular carcinomas using gene expression profiling and supervised machine learning. Nat Med. 2003;9:416–423. doi: 10.1038/nm843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Portolani N, Coniglio A, Ghidoni S, Giovanelli M, Benetti A, Tiberio GA, Giulini SM. Early and late recurrence after liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma, Prognostic and therapeutic implications. Ann Surg. 2006;243:229–235. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000197706.21803.a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, Mars WM, Sullivan AK, Murase N, Boggs SS, Greenberger JS, Goff JP. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science. 1999;284:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jang YY, Collector MI, Baylin SB, Diehl AM, Sharkis SJ. Hematopoietic stem cells convert into liver cells within days without fusion. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:532–539. doi: 10.1038/ncb1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alison MR, Lovell MJ. Liver cancer: The role of stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2005;38:407–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2005.00354.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li GC, Ye QH, Xue YH, Sun HJ, Zhou HJ, Ren N, Jia HL, Shi J, Wu JC, Dai C, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells inhibit metastasis of a hepatocellular carcinoma model using the MHCC97-H cell line. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2546–2553. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rakesh KJ, Dan GD, Christopher GW, Dushyant VS, Andrew XZ, Jay SL, Tracy TB. Biomarkers of response and resistance to antiangiogenic therapy. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:327–338. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poon RT, Ng IO, Lau C, Yu WC, Yang ZF, Fan ST, Wong J. Tumor microvessel density as a predictor of recurrence after resection of hepatocellular carcinoma, A prospective study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:1775–1785. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.07.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qin LX, Tang ZY. Recent progress in predictive biomarkers for metastatic recurrence of human hepatocellular carcinoma: A review of the literature. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:497–513. doi: 10.1007/s00432-004-0572-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lyden D, Hattori K, Dias S, Costa C, Blaikie P, Butros L, Chadburn A, Heissig B, Marks W, Witte L, et al. Impaired recruitment of bone-marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumour angiogenesis and growth. Nat Med. 2001;7:1194–1201. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reyes M, Dudek A, Jahagirdar B, Koodie L, Marker PH, Verfaillie CM. Origin of endothelial progenitors in human postnatal bone marrow. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:337–346. doi: 10.1172/JCI0214327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kinnaird T, Stabile E, Burnett MS, Shou M, Lee CW, Barr S, Fuchs S, Epstein SE. Local delivery of marrow-derived stromal cells augments collateral perfusion through paracrine mechanisms. Circulation. 2004;109:1543–1549. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000124062.31102.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bellone G, Gramigni C, Vizio B, Mauri FA, Prati A, Solerio D, Dughera L, Ruffini E, Gasparri G, Camandona M. Abnormal expression of Endoglin and its receptor complex (TGF-β1 and TGF-β receptor II) as early angiogenic switch indicator in premalignant lesions of the colon mucosa. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:1153–1165. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo SW, Ke FC, Chang GD, Lee MT, Hwang JJ. Potential role of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and transforming growth factor (TGFβ1) in the regulation of ovarian angiogenesis. J Cell Physiol. 2011;226:1608–1619. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzocca A, Fransvea E, Lavezzari G, Antonaci S, Giannelli G. Inhibition of transforming growth factor beta receptor I kinase blocks hepatocellular carcinoma growth through neo-angiogenesis regulation. Hepatology. 2009;50:1140–1151. doi: 10.1002/hep.23118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, et al. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Tang ZY, Ye SL, Liu YK, Chen J, Xue Q, Chen J, Gao DM, Bao WH. Establishment of cell clones with different metastatic potential from the metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line MHCC97. World J Gastroenterol. 2001;7:630–636. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i5.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Y, Tang Y, Ye L, Liu B, Liu K, Chen J, Xue Q. Establishment of a hepatocellular carcinoma cell line with unique metastatic characteristics through in vivo selection and screening for metastasis-related genes through cDNA microarray. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2003;129:43–51. doi: 10.1007/s00432-002-0396-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferdowsian H. Human and animal research guidelines: A ligning ethical constructs with new scientific developments. Bioethics. 2011;25:472–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2011.01923.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen ZY, Wei W, Guo ZX, Lin JR, Shi M, Guo RP. Morphologic classification of microvessels in hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with the prognosis after resection. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26:866–874. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun HC, Tang ZY, Li XM, Zhou YN, Sun BR, Ma ZC. Microvessel density of hepatocellular carcinoma, Its relationship with prognosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1999;125:419–426. doi: 10.1007/s004320050296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gasparini G. Prognostic value of vascular endothelial growth factor in breast cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(Suppl 1):37–44. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-suppl_1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Littlepage LE, Egeblad M, Werb Z. Coevolution of cancer and stromal cellular responses. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:499–500. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leek RD, Harris AL, Lewis CE. Cytokine networks in solid human tumors, Regulation of angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;56:423–435. doi: 10.1002/jlb.56.4.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oft M, Heider KH, Beug H. TGFbeta signaling is necessary for carcinoma cell invasiveness and metastasis. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(07)00533-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyer S, Wang ZG, Akhtari M, Zhao W, Seth P. Targeting TGFbeta signaling for cancer therapy. Cancer Biol Ther. 2005;4:261–266. doi: 10.4161/cbt.4.3.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welm AL. TGFβ primes breast tumor cells for metastasis. Cell. 2008;133:27–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes Dev. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–129. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Salcedo X, Medina J, Sanz-Cameno P, García-Buey L, Martín-Vilchez S, Moreno-Otero R. Review article Angiogenesis soluble factors as liver disease markers. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:23–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brogi E, Wu T, Namiki A, Isner JM. Indirect angiogenic cytokines upregulate VEGF and bFGF gene expression in vascular smooth muscle cells, whereas hypoxia upregulates VEGF expression only. Circulation. 1994;90:649–652. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.90.2.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Greenbaum D, Colangelo C, Williams K, Gerstein M. Comparing protein abundance and mRNA expression levels on a genomic scale. Genome Biol. 2003;4:117. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-9-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferrari G, Pintucci G, Seghezzi G, Hyman K, Galloway AC, Mignatti P. VEGF, a prosurvival factor, acts in concert with TGF-beta1 to induce endothelial cell apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17260–17265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605556103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jeon SH, Chae BC, Kim HA, Seo GY, Seo DW, Chun GT, Kim NS, Yie SW, Byeon WH, Eom SH, et al. Mechanisms underlying TGF-beta1-induced expression of VEGF and Flk-1 in mouse macrophages and their implications for angiogenesis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81:557–566. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0806517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee KS, Park SJ, Kim SR, Min KH, Lee KY, Choe YH, Hong SH, Lee YR, Kim JS, Hong SJ, Lee YC. Inhibition of VEGF blocks TGF-beta1 production through a PI3K/Akt signalling pathway. Eur Respir J. 2008;31:523–531. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00125007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrari G, Cook BD, Terushkin V, Pintucci G, Mignatti P. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-beta1) induces angiogenesis through vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-mediated apoptosis. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219:449–458. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]