Abstract

Primary localized amyloidomas of the renal pelvis are challenging to diagnose, due to non-specific imaging results and the unusual location. The present study reports a rare case of primary localized amyloidoma of the renal pelvis and aims to illustrate the challenges in pre-operatively discriminating between this disease and transitional cell carcinomas. The present study identified that the mass was situated in the left renal pelvis using ultrasonography. A nephroureterectomy was performed following careful preparation. Finally, histopathological studies revealed that the tumor consisted of massive diffuse deposits of amyloid and microscopic amorphous eosinophilic material, which stained positively for Congo red, demonstrating potassium permanganate digestion. Consequently, a diagnosis of amyloid light chain-type amyloidoma was determined. Systematic examinations were performed following the unexpected diagnosis, which eliminated the possibility of amyloid associated-type amyloidoma. In total, 4 months post-surgery, the patient remained tumor-free.

Keywords: amyloidoma, renal pelvis, nephrectomy

Introduction

Localized amyloidoma is generally divided into two styles: AL-type and AA-type. AL-type occurs with an immunocyte dyscrasia while AA-type occurs with chronic infection, non-immunocyte neoplasia or inflammation. Localized amyloidoma occurs most often in the mediastinum or abdomen. Although amyloidomas may occur in almost all organ systems in the body; however, primary amyloidoma of the renal pelvis is rare. Using the keywords: ‘renal pelvis’, ‘amyloidoma’ and ‘amyloid tumor’ and search terms (renal pelvis) and (amyloidoma or amyloid tumor) in PubMed (National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA), a literature search was performed and only 26 cases of primary amyloidomas of the renal pelvis were identified (Table I) (1–23). Primary localized amyloidoma may present as hematuria and lumbago (14). A primary localized amyloidoma of the renal pelvis consists of amyloid deposits that may present as malignant tumors (15). The present study reports the rare case of a patient with amyloidoma that was confined to the renal pelvis, and the patient exhibited similar symptoms to those of upper urinary tract transitional cell carcinoma (TCC). In addition, 26 cases of patients with primary amyloidoma of the renal pelvis identified from the literature were also reviewed. Nephrectomy was the most selected treatment in the reported cases. The majority of patients achieved long time disease free survival and good prognosis. (7). The clinical and pathological features of the cases were discussed, in particular, the treatment methods and prognosis.

Table I.

Review of the reported cases of primary localized amyloidoma of the renal pelvis.

| First author, year (Ref.) | Gender | Age, years | Symptoms or clinical finding | Medical history | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Akimoto, 1927 (22) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Gilbert et al, 1952 (1) | F | 52 | Flank pain | NA | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Sato, 1957 (23) | M | 37 | Hematuria and flank pain | None | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Chisholm et al, 1967 (2) | M | 66 | Painless hematuria | None | Nephrectomy | Succumbed to renal failure following a short period of time |

| Chisholm et al, 1967 (2) | F | 58 | Iron-deficiency anemia and mild azotemia | None | Nephrostomy | Alive with no evidence of disease |

| Gardner et al, 1971 (3) | M | 39 | Left flank pain and rust-colored urine | None | Biopsy of renal pelvis | Alive with no evidence of disease |

| Ullmann, 1973 (4) | F | 58 | Hematuria and flank pain | NA | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Dias et al, 1979 (5) | F | 67 | Painless gross hematuria | Left hemicolectomy for carcinoma of the sigmoid colon | Nephrectomy/partial ureterectomy | Succumbed to unknown causes 3 years later |

| Gelbard et al, 1980 (6) | M | 67 | Left flank pain and gross hematuria | Cardiovascular accident incurred during a total hip replacement for osteoarthritis | Radical nephrectomy | NA |

| Fujibara et al, 1981 (7) | M | 66 | Hematuria | N.A | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Fox et al, 1984 (8) | M | 81 | Painless hematuria | None | Nephroureterectomy | NA |

| Murphy et al, 1986 (9) | F | 67 | Hematuria and left flank pain | Tuberculosis of the chest, spine and right breast | Nephroureterectomy | NA |

| Davis et al, 1987 (10) | M | 58 | Intermittent gross hematuria | None | Nephroureterectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 5 years later |

| Sparwasser et al, 1991 (11) | M | 81 | Hematuria | Contusion of the left kidney and labile hypertension | Nephrectomy/proximal ureterectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 5 years later |

| Shiramizu et al, 1992 (12) | F | 63 | Left flank pain and gross hematuria | None | Nephroureterectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease |

| German, 1994 (13) | M | 64 | Diarrhea, vomiting and urinary frequency | None | Amyloid material cleared by laparotomy | Obstruction and perforation at the pelvi-ureteric junction by sharp calculus Succumbed to pneumonia 8 months later |

| Tsuji et al, 1994 (19) | F | 47 | Intermittent gross hematuria and right flank pain | Right mastectomy | Ieal ureter | Alive with no evidence of disease 2 years later |

| Merrimen et al, 2006 (14) | F | 51 | Flank pain, fever and gross hematuria | None | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Borza et al, 2010 (15) | M | 58 | Gross, painless hematuria and right flank pain | None | Active surveillance | No clinical or radiographical signs of progressive disease 6 years later |

| Pan et al, 2011 (16) | M | 70 | None | Partial nephrectomy of the right kidney for an angiomyolipoma 4 years prior | Active surveillance | Recurrence in the unilateral bladder and ureter |

| Monge et al, 2011 (17) | M | 68 | Gross hematuria and renal colic | None | Nephrectomy, repeated, resections double J stent | No recurrence. Only mild renal insufficiency remained 5 years later |

| Paidy et al, 2012 (20) | F | 72 | Gross hematuria and right flank pain | Nephrolithiasis, hypertension, osteoarthritis stroke, transient ischemic attack, atrial fibrillation and hypercholesterolemia | Nephrectomy | NA |

| Zhou et al, 2014 (21) | F | 77 | Gross hematuria | None | Nephrectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 12 years later |

| Zhou et al, 2014 (21) | M | 71 | Gross hematuria | None | Nephrectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 6 years later |

| Grigor, 2015 (18) | F | 60 | Gross hematuria intraepithelial | Supraventricular tachycardia, neoplasia. Retinal detachment, macular hole and cervical lattice degeneration in right eye | Laparoscopic nephrectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 30 months later, but diagnosed with breast cancer 21 months ago |

| Present study | M | 56 | Gross hematuria | Kidney calculi | Nephrectomy | Alive with no evidence of disease 4 months later |

NA, not available; M, male; F, female.

Case report

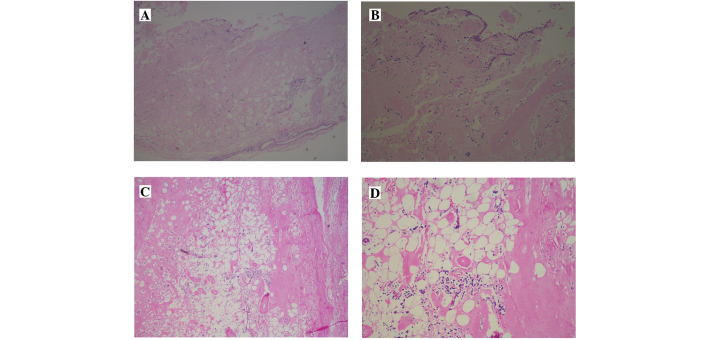

A 56-year-old man presented to the Department of Urology, Sun-Yat Sen University Cancer Center (Guangzhou, China) with left flank pain, symptoms of urinary irritation and intermittent gross hematuria. The patient had experienced the symptoms for 6 years; however, in the month prior to presentation, the symptoms had become worse. Ultrasonography revealed a mass with a low-intensity heterogeneous pattern that measured 55×19 mm in size and obstructed the lumen of the renal pelvis. Dilatation of the renal pelvis was located in the left kidney (Fig. 1). A preliminary diagnosis of TCC of the renal pelvis was suggested based on sonography, and therefore, a nephroureterectomy was advised. However, 5 urinary cytology tests were negative and pre-operative examinations revealed no abnormal signs, such as abdominal tenderness or rebound pain, during physical examination. Blood tests yielded the following results: Urine protein, 2+; urine red blood cell count, >3 cells/high power field; urine erythrocytes, 932 µl/l; left renal glomerular fitration rate, 18 ml/min; right renal glomerular fitration rate, 64ml/min; and the serum creatinine levels, eosinophil numbers and basophil numbers were within the normal ranges. The patient had been a smoker for ~20 years and had suffered from nephrolithiasis for 6 years. The patient possessed no known drug allergies. Subsequently, the patient agreed to undergo a nephroureterectomy.

Figure 1.

Ultrasound scans revealed that the mass exhibited a low heterogeneous echo with an irregular shape, and was located in the left renal pelvis and measured 55×19 mm in size.

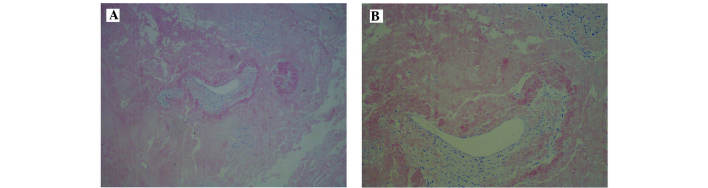

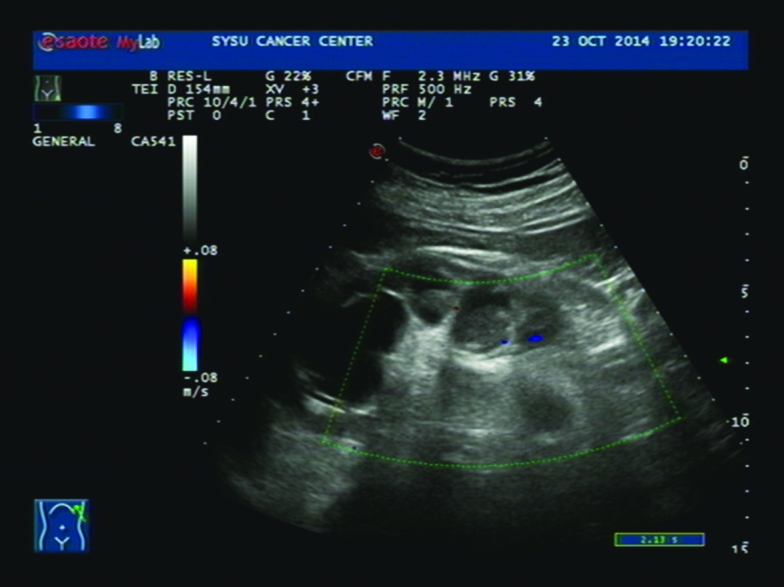

Following surgery, the excised mass underwent additional tests. Macroscopically, the surgical specimen revealed tumors located in the renal pelvis. No clear difference in the ureter was observed. A cut section of the tumor revealed a red-yellow surface with firm regions. Microscopically, histopathological studies revealed that the tumor consisted of massive diffuse deposits of amyloid and microscopic, eosinophilic, amorphous material (Fig. 2) and an absence of neoplastic cells. The tumor stained positive for Congo red (Fig. 3), which indicates the presence of material that is retained following potassium permanganate digestion. A final diagnosis of amyloid light chain-type amyloidoma of the renal pelvis was determined. The patient received regular surveillance and was alive with no evidence of disease 5 months later.

Figure 2.

Light microscopy revealed that amyloid had been deposited in the renal pelvis, fat and vasculature. Massive amyloid deposits were located in the renal pelvis [magnification, (A) ×40 and (B) ×100] and the vasculature [magnification, (C) ×40 and (D) ×100].

Figure 3.

Congo red stain revealed the presence of a red-brown material in the renal pelvis and vasculature. Magnification, (A) ×40 and (B) ×100.

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of the present study.

Discussion

Amyloidosis refers to a large heterogeneous group of diseases that is characterized by extracellular deposits of amyloid in individual organs or tissue. Amyloid is an amorphous, insoluble and proteinaceous material (17). Extracellular amyloidosis consists of specific protein fibrils (24). Amyloidosis can be classified into 4 groups, consisting of primary, secondary, heredofamilial and β2-microglobulin-associated amyloidosis. This disease may be additionally classified as localized amyloidosis, which involves a single organ, or systemic amyloidosis, which involves multiple organs and is the most common classification among reported cases (6). By contrast, localized amyloidosis occurs much less frequently. (15) Systemic amyloidosis may be primary, progressive and fatal. Primary amyloidosis is commonly associated with an underlying immune dyscrasia, such as multiple myeloma and Waldenstrom's macroglobulinemia (15).

The etiology of primary localized urinary amyloidosis remains unknown; however, it may be possible that amyloid deposits are produced locally, or the submucosa of the genitourinary tract may be targeted by light-chains that are produced elsewhere. Numerous studies support the first hypothesis, as there is an absence of a monoclonal plasma component. An additional hypothesis is that protein deposits in bladder non-amyloid associated (AA) localized amyloidosis consist of the immunoglobulin λ light-chain subgroup I or IV (17).

Furthermore, non-AA localized amyloidosis has been described in the lung (25), nervous system (26), skin (24), larynx (27), intestinal tract (28) and genitourinary tract (17). Using PubMed, a literature search was performed and only 26 cases of primary amyloidomas of the renal pelvis were identified. The inclusion and exclusion criteria is whether primary localized amyloidoma. The majority of reported cases concerned with localized urinary tract amyloidosis are characterized as primary type, but secondary localized amyloidosis has been reported without a chronic systemic inflammatory state. Renal pelvis primary localized amyloidoma is an extremely rare condition, and is notable due to its clinical presentation and radiographic appearance, which mimics that of transitional cell carcinoma. In a review of the English and French literature by Monge et al (17), 169 cases of genitourinary tract localized amyloidoma were reported over the past 100 years. The renal pelvis was the most rare location identified, accounting for ~6% of the 169 cases, which was lower than the number located in the bladder, ureter and urethra. To the best of our knowledge, only 26 cases of renal pelvis primary localized amyloidoma have been reported (1–23).

Positive staining for Congo red is used to diagnose primary localized amyloidoma. In order to exclude AA-type amyloidosis, screening by pre-exposure of tissue slides to KMnO4 stain is performed, since false-negative results may be obtained using immunohistochemistry (negative for Congo red) (17). Clinical symptoms of primary localized amyloidoma of the renal pelvis typically present as gross hematuria, flank pain and urinary irritative symptoms, which mimic the symptoms of inflammation and neoplasm (21). It is challenging to distinguish between amyloidoma and upper urinary tract TCC solely from radiological findings, which may be non-specific (17). In addition, urine cytology does little to contribute to the diagnosis, since the majority of amyloid deposits are subepithelial. Consequently, to avoid misdiagnosis, upper urinary tract tumors should be evaluated microscopically by ureteroscopic biopsy when multiple urine cytology analyses are negative, or if possible, by surgical biopsy using frozen tissue sections examined prior to radical resection.

Primary localized amyloidoma possesses a relatively good prognosis in the genitourinary tract and other organ systems. Recurrence and implantation of the tumor has not been identified in reported cases. Nephrectomy was the chosen treatment in the present study, and is used in the majority of reported cases. However, by monitoring the progression of the primary localized amyloid tumor in the renal pelvis, using active surveillance with serial imageological examination, a similar outcome to nephrectomy may be observed (15). This should be considered by all urologists.

Primary localized amyloidoma is extremely rare in the renal pelvis (14,15). Consequently, there is a lack of standardized clinical symptoms and specific laboratory tests, and in addition, imageological examination mimics TCC. A pre-operative ureteroscopic biopsy or surgical biopsy is required when multiple urinary cytology analyses are not positive or a benign tumor, including primary localized amyloidoma, is suspected, to avoid an unnecessary nephroureterectomy. Early radical surgery is not required unless there is no renal function or a severe urinary tract obstruction. Instead, active surveillance with serial imageological examination may be used to monitor the progression of the lesion. In conclusion, primary localized amyloidoma of renal pelvis is a benign and rare tumor, which has a relatively good prognosis.

References

- 1.Gilbert LW, McDonald JR. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis and ureter: Report of case. J Urol. 1952;68:137–139. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(17)68179-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chisholm GD, Cooter NB, Dawson JM. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis. BMJ. 1967;1:736–738. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5542.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gardner KD, Jr, Castellino RA, Kempson R, Young BW, Stamey TA. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis. N Engl J Med. 1971;284:1196–1198. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197105272842107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ullmann AS. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis: A case report and review of literature. Mich Med. 1973;72:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dias R, Fernandes M, Patel RC. deS hadarevian JJ and Lavengood RW: Amyloidosis of renal pelvis and urinary bladder. Urology. 1979;14:401–404. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(79)90092-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gelbard M, Johnson S. Primary amyloidosis of renal pelvis and renal cortical adenoma. Urology. 1980;15:614–617. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(80)90382-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fujihara S, Glenner GG. Primary localized amyloidosis of the genitourinary tract: Immunohistochemical study on eleven cases. Lab Invest. 1981;44:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fox M, Hammond JC, Knox R, Underwood JC. Localised primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis. Br J Urol. 1984;56:223–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1984.tb05369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy MN, Alguacil-Garcia A, MacDonald RG. Primary amyloidosis of renal pelvis with duplicate collecting system. Urology. 1986;27:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(86)90420-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis PS, Babaria A, March DE, Goldberg RD. Primary amyloidosis of the ureter and renal pelvis. Urol Radiol. 1987;9:158–160. doi: 10.1007/BF02932650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sparwasser C, Gilbert P, Mohr W, Linke RP. Unilateral extended amyloidosis of the renal pelvis and ureter, A case report. Urol Int. 1991;46:208–210. doi: 10.1159/000282135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shiramizu M, Nakamura K, Baba S, Katsuoka Y, Kinoshita H. Primary localized amyloidosis of the renal pelvis coexisting with transitional cell carcinoma, A case report. Hinyokika Kiyo. 1992;38:699–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.German KA, Morgan RJ. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis and upper ureter. Br J Urol. 1994;73:99–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.1994.tb07466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merrimen JL, Alkhudair WK, Gupta R. Localized amyloidosis of the urinary tract, Case series of nine patients. Urology. 2006;67:904–909. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Borza T, Shah RB, Faerber GJ, Wolf JS., Jr Localized amyloidosis of the upper urinary, tract. A case series of three patients managed with reconstructive surgery or surveillance. J Endourol. 2010;24:641–644. doi: 10.1089/end.2009.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pan DL, Na YQ. Amyloidosis of the unilateral renal pelvis ureter and urinary bladder: A case report. Chin Med Sci J. 2011;26:197–200. doi: 10.1016/S1001-9294(11)60049-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monge M, Chauveau D, Cordonnier C, Noël LH, Presne C, Makdassi R, Jauréguy M, Lecaque C, Renou M, Grünfeld JP, et al. Localized amyloidosis of the genitourinary tract: Report of 5 new cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 2011;90:212–222. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31821cbdab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grigor T, Munro N. Amyloidosis of the renal pelvis: A harbinger of mammary carcinoma? BMJ Case Rep. 2015;16:2015. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-207955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuji Y, Michinaga S, Ariyoshi A. Ileal ureter, Another option for the treatment of localized amyloidosis of the upper urinary tract. J Urol. 1994;151:999–1000. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35148-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paidy S, Unold D, Catanzano TM. AIRP best cases in radiologic-pathologic correlation, localized amyloidosis of the renal pelvis. Histopathology. Inc. 2012;32:2025–2030. doi: 10.1148/rg.327115157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhou F, Lee P, Zhou M, Melamed J, Deng FM. Primary localized amyloidosis of the urinary tract frequently mimics neoplasia, A clinicopathologic analysis of 11 cases. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2014;2:71–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akimoto K. Ober amyloidartigeE iweissniederschlage im Nierenbecken. Beitr Pathol Anat. 1927;78:239. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sato S. Primary amyloidosis of the renal pelvis and ureter: R eport of a case. Acta Med Biol. 1957;5:15. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Reitboeck JG, Feldmann R, Loader D, Breier F, Steiner A. Primary cutaneous amyloidoma, A case report. Case Rep Dermatol. 2014;6:264–267. doi: 10.1159/000369245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dong MJ, Zhao K, Liu ZF, Wang GL, Yang J. Primary pulmonary amyloidosis misdiagnosed as malignancy on dual-time-point fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2015;9:591–594. doi: 10.3892/ol.2014.2778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Apostolova LG, Hwang KS, Avila D, Elashoff D, Kohannim O, Teng E, Sokolow S, Jack CR, Jagust WJ, Shaw L, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: Brain amyloidosis ascertainment from cognitive, imaging, and peripheral blood protein measures. Neurology. 2015;84:729–737. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng KJ, Wang SQ, Lin S. Localized amyloidosis concurrently involving the nasopharynx, larynx and nasal cavities, A case report. Zhonghua Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2009;44:875–876. (In Chinese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yaita H, Nakamura S, Kurahara K, Nagasue T, Kochi S, Oshiro Y, Ohshima K, Ikeda Y, Fuchigami T. Primary small-bowel adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma with gastric AL amyloidosis. Endoscopy. 2014;46:E613–614. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]