Abstract

In the present study, the case of a female patient with pseudo-hermaphrodism caused by an androgen-producing adrenocortical tumor is presented, and the possible mechanism is investigated. The expression of the luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotrophin (LH/hCG) receptor in tumor tissues and normal adrenal tissues was analyzed using immunohistochemistry. Furthermore, the activities of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (HSD2), cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase (CYP17) and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 (HSD3) enzymes were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, and the expression levels of 3β-HSD2, 17β-HSD3, CYP17 and LH/hCG receptor mRNA were determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR). Immunohistochemical staining for the LH/hCG receptor was negative in the tumor tissue and positive in the normal adrenal tissue. The activities of 3β-HSD2 and CYP17 in the tumor tissue were higher than those in the normal tissue (P<0.01), whereas the activity of 17β-HSD3 was lower (P<0.01). The mRNA levels of 3β-HSD2 and CYP17 were higher (P<0.01) and the levels of 17β-HSD3 and LH/hCG receptor were lower (P<0.01) in the tumor tissue compared with those of the normal tissue. In conclusion, in the present study, a rare case of virilization by an androgen-producing adrenocortical tumor is present. The results indicate that it may be associated with increased activities of 3β-HSD2 and CYP17 but not with the expression of the LH/hCG receptor.

Keywords: androgen-producing adrenocortical tumor, pseudo-hermaphrodism, virilization, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, 17α-hydroxylase

Introduction

The most common cause of female pseudo-hermaphrodism is congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH); however this condition may also be caused by an androgen-secreting adrenal tumor (1–3). Androgen-secreting adrenal tumors, also known as virilizing adrenal tumors, produce excessive amounts of androgen and are primarily found in females. In pre-adolescent females, this presents as pseudo-hermaphrodism (4), whilst for adolescent and adult females this presents as varied degrees of virilization. The majority of tumors are malignant. The benign tumors may be normalized with surgery; virilization may be alleviated and the menses of the patients may resume (5). Therefore, early detection is extremely important for treatment. However, there are limited methods for early detection. Thus, in the present study, a case of pseudo-hermaphrodism caused by an adrenal adenoma in an adolescent female is presented and the possible mechanism investigated, with the hope that this may guide early diagnosis and treatment.

Case report

Case summary

A 15-year-old female was admitted to the Department of Endocrinology, PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China) on August 10, 2011 ago due to abnormal external genitalia, discovered 12 years previously. Since childhood, the patient had dark skin, a low, deep voice, excessive body hair and an enlarged clitoris. From the age of 12 years, breast development started and scanty dark hairs appeared above the patient's lip. The results from the physical examination upon admission were as follows: height, 138 cm; body weight, 36 kg; blood pressure, 170/120 mmHg; and heart rate, 108 bpm. The breasts were symmetrical, Tanner Stage II. Hypertrophy of the clitoris was observed and the pubic hairs were dark and thick, Tanner stage IV. The karyotype was 46, XX. As shown in Table I, there was no abnormality in the biochemical profile of the patient, nor were there abnormalities in her growth hormone and insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) levels. Testosterone was observed to be elevated (3.35 nmol/l), and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEAS) and 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels were slightly elevated. Circadian rhythm of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol, as well as serum and urinary aldosterone levels and renin activities, were normal.

Table I.

Laboratory results prior to and following surgery.

| Variable | Prior to surgery | Following surgery | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum potassium (mmol/l) | 3.54 | 4.29 | 3.5–5.5 |

| Urinary free cortisol (nmol/l) | 440.5 | 185.5 | 98–500 |

| Serum cortisol at 8:00 a.m. (nmol/l) | 245.9 | – | 198.7–797.5 |

| Cortisol (nmol/l) | 25.6 | – | – |

| Serum ACTH at 8:00 a.m. (pmol/l) | 7.64 | – | <10 |

| ACTH (pmol/l) | 1.11 | – | – |

| Testosterone (nmol/l) | 3.35 | 0.34 | 0.5–2.6 |

| LH (mIU/ml) | 14.63 | 11.9 | 0.5–76.3 |

| FSH (mIU/ml) | 6.42 | 4.14 | 1.5–33.4 |

| E2 (pmol/l) | 221.3 | 343.2 | 48.2–1531.8 |

| 17-hydroxyprogesterone (ng/ml) | 3.45 | 0.38 | 0.6–3.34 |

| DHEAS (µg/dl) | 464 | 15.0 | 35–430 |

ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; DHEAS, dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate.

X-ray imaging revealed closed epiphyses. The ultrasound (U/S) investigation showed normal ovaries and a small uterus. A non-uniform mass was detected at the right adrenal area by U/S, which was ~11.4×6.9×9.4 cm in size. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scans indicated that it was a mixed cystic and solid occupying mass in the right adrenal area, with non-uniform density and enhancement with contrast (Fig. 1A). This is consistent with the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan, in which a large solid mass, rich in lipids and vessels, with local necrosis was observed (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Adrenal CT. On the right side of the adrenal area, there is round soft tissue shadow, non-uniform, with multiple cystic low density shadows and multiple dotted high density shadows. (B) Adrenal MRI. There is a 115×77×79 mm3 mass on the right side of the adrenal area. There are significant non-uniform enhancements in the lesion during the arterial phase, which are gradually enhanced in the solid and delayed phases. There is a cystic non-enhanced area in the lesion. The red arrow indicates the tumor.

The patient was diagnosed with an androgen-secreting adrenal adenoma. The tumor was removed with an intact envelope (Fig. 2). Pathology confirmed that it was an adrenal adenoma (Fig. 3). Four days following the surgery, testosterone, DHEAS and 17-hydroxyprogesterone levels dropped (Table I). After three months, the patient experienced her menarche, the amount of body hair was reduced and there was no further development of the breasts. The blood pressure of the patient remained at 130–140/90–100 mmHg without antihypertensive medication.

Figure 2.

General appearance of the adrenal tumor. It is a gray-whitish-brownish tumor, sized at 12×7.5×5 cm3, with the majority of the envelope intact, solid, nodule-like and yellow-brownish, with local necrosis.

Figure 3.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining and immunohistochemistry of the adrenal tumor. (A) magnification, ×100; (B) magnification, ×1000.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples

Tumor tissues were obtained from the adrenal adenoma and control samples were obtained from normal adrenal tissues. Immediately upon removal, the tissues were stored in liquid nitrogen for further analysis. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the PLA general hospital and written informed consent was obtained from the patient prior to participation in the study.

Immunohistochemical staining

Sections were immunostained for luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotrophin (LH/hCG) receptors using the avidin-biotin immunoperoxidase method and detected with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Rabbit anti-human LH receptor (LHR) polyclonal antibody was used as the primary antibody and biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) as the secondary antibody (Bioss, Inc., Woburn, MA, USA).

Under a microscope, brown staining of the membrane was regarded as positive expression. Ten fields were randomly selected for each slice. The results were graded according to the percentage of positive cells among the same type of cells as follows: (−), no positive cells visible or the number of positive cells was <25%; (+), number of positive cells was 25–50%; (++), number of positive cells was 50–75%; (+++) number of positive cells was >75%.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

The ABC ELISA kits were purchased from Shanghai XiTang Biotechnology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). The standard solutions were prepared and the assays of tissue sample homogenates were conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions. The integrated optical density was measured at 450 nm for 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 2 (HSD2), cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase (CYP17) and 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3 (HSD3) to determine the activities of these enzymes.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR)

qPCR was performed to detect the relative quantities of the mRNA of GAPDH (control) 3β-HSD2, 17β-HSD3, CYP17 and LH/hCGR genes using SYBR Green RT-qPCR reagents kit (Applied Biosystems™, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the instructions of the manufacturer and as previously described (6). The primers were as follows: GAPDH forward, 5′-caatgaccccttcattgacc-3′ and reverse, 5′-GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG-3′; 3β-HSD2 forward, 5′-AGCTTCCTACTCAGCCCAAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TACCCACATGCACATCTCTG-3′; 17β-HSD3 forward, 5′-GGCTGCTCCTGACACACTAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTCAGCGGACTAGGTTGAAG-3′; CYP17 forward, 5′-ACATGCTGGACACACTGATG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAGGGTCCATTTAACCACAG-3′; LH/hCGR forward, 5′-GCCAATCCATTTCTGTATGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GTGCAATGTGGACAACTTCA-3′.

Statistical analysis

IBM SPSS statistics software, version 19.0, was used to conduct the statistical analyses (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) and a t-test was performed for comparison between the groups. Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference.

Results

Immunohistochemistry for the LH/hCG receptor

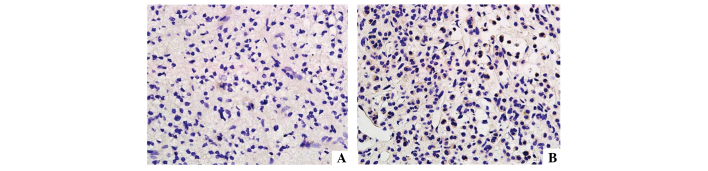

As shown in Fig. 4, the LH/hCG receptor was not expressed in tumor tissues (<25% positive cells). However, in normal tissue high expression levels were observed (+++, >75% positive cells).

Figure 4.

Immunohistochemistry of luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotrophin receptor in (A) tumor tissue and (B) normal tissue.

3β-HSD2, 17β-HSD3 and CYP17 enzyme activities

3β-HSD2, CYP17 and 17β-HSD3 concentrations in tissue homogenates were detected by ABC-ELISA. The levels of 3β-HSD2 (1,819±10.8 pg/ml) and CYP17 (93.5±2.73 µmol/ml) in the tumor tissue were higher than those of the normal tissues (1,458±29.6 pg/ml and 58.6±1.96 µmol/ml, respectively; P<0.01), while the level of 17β-HSD3 (2,639±70.6 pg/ml) in the tumor tissue was lower compared with that of normal tissues (9,148±383 pg/ml; P<0.01).

Relative mRNA levels of 3β-HSD2, 17β-HSD3, CYP17 and LH/hCG receptor genes

As shown in Table II, the mRNA levels of 3β-HSD2 and CYP17 were higher (P<0.01), while those of 17β-HSD3 and LH/hCG receptor genes were lower (P<0.01) in the tumor tissues than in the normal tissues.

Table II.

Relative mRNA levels of 3β-HSD2, 17β-HSD3, CYP17 and LH/hCG receptor genes in tissue homogenates.

| mRNA | Normal tissue | Tumor tissue |

|---|---|---|

| 3β-HSD2 | 3.501±0.312 | 13.960±3.977a |

| 17β-HSD3 | 4.517±0.225 | 0.962±0.288a |

| CYP17 | 0.995±0.208 | 6.173±0.982a |

| LH/hCG receptor | 4.209±0.585 | 1.098±0.087a |

P<0.01, compared with the value in normal tissue. 3β-HSD2, 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase; 17β-HSD3, 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase 3; CYP17, cytochrome P450 17α-hydroxylase; LH/hCG, luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotrophin.

Discussion

Androgen-secreting adrenal tumors are rare. The tumors are usually malignant; however, certain tumors may be benign (7). It has reported that only 11 patients with purely androgen-secreting tumors were identified at Mayo Clinic (Rochester, MN, USA) for more than >50 years (8). In the past 18 years in the PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China), only two cases (0.13%) have been diagnosed as androgen-secreting adrenal tumors among 1,494 cases of adrenal tumors.

In the present case, virilization, hormone levels, CT and MRI scans all supported the diagnosis of an androgen-secreting adrenal tumor, which was further confirmed by the pathological analysis. Following surgical removal of the tumor, the testosterone level of the patient returned to normal, suggesting that excessive amounts of testosterone had been secreted by the tumor.

Testosterone levels were significantly elevated in the patient due to the androgen-secreting adrenal adenoma. The DHEAS and urinary 17-ketosteroid (17-KS) levels were increased significantly but not suppressed by dexamethasone, suggesting their autonomous and independent secretion without ACTH. Since the levels of CYP21 and CYP11 are normal or reduced, the aldosterone, cortisol and urinary metabolite 17-hydroxycorticosteroid (17-OHCS) levels are usually normal (9,10). Thus, only a quarter of virilizing adrenal tumors are accompanied by Cushing's syndrome and the majority of them are malignant (11). In the present case, circadian rhythm of ACTH and cortisol, urinary free cortisol, serum and urinary aldosterone levels and renin activity were all normal, indicating that the adrenal mass did not secrete excessive amounts of cortisol and aldosterone.

Previous studies have demonstrated that 3β-HSD and 17β-HSD3 but not 11β-HSD, are highly expressed in androgen-secreting adrenal tumors, suggesting that the abnormal secretion of androgen may be associated with changes of enzyme activities during steroid synthesis (12,13). The elevated enzyme activity of 3β-HSD and CYP17 drives the synthesis towards androgen production, and subsequently to the production of DHEA and 17-hydroprogesterone, some of which is then converted into estradiol and testosterone (14). This may explain the serum levels observed in the patient of the present study, and suggest a simple method for the early detection of androgen-secreting adrenal tumors.

In addition, the results of present study demonstrated that LH/hCG receptors were expressed in adrenal cortex cells. These receptors regulate steroid synthesis and secretion, and may stimulate cortisol or androgen secretion when LH/hCG is present. Numerous studies have confirmed that Cushing's syndrome and hyperaldosteronism are closely associated with the overexpression of LH/hCG receptors (15,16). Although a few cases of an association between the adrenal overexpression of the LH/hCG receptor and virilization have been reported (17,18), studies investigating the association between androgen synthesis and the LH/hCG receptor are limited.

The results of the present study showed there was no expression LH/hCG receptor in normal adrenal tissue, suggesting negative feedback from accelerated steroid synthesis caused by elevated 3β-HSD and CYP17 enzyme activities. Furthermore, other hormones, including ACTH, cortical androgen-stimulating hormone, pro-opiomelanocortin, IGF-1 and prolactin regulate androgen secretion (19–21). However, this requires further study.

In the present report, a rare case of an androgen-secreting adrenal tumor is presented. Due to the limited clinical samples and materials, this study focused on the tissue from a single case and investigated the possible mechanism; however, it may not be representative of all cases.

In conclusion, the results from the present study suggest that virilization in adrenal adenoma may be associated with the overexpression of 3β-HSD and CYP17, resulting in elevated enzymatic activities, but not the expression of the LH/hCG receptor in adrenal cells. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study indicating this association, and it may represent a potential target for early diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the patient who consented to this study and all the staff involved in this study.

References

- 1.Rohana AG, Ming W, Norlela S, Norazmi MK. Functioning adrenal adenoma in association with congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Med J Malaysia. 2007;62:158–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bédrine H D.M., Mangeot JP, Bégueri F. Familial male pseudo-hermaphrodism of karyotype XY and ambiguous morphology. Gynecol Obstet (Paris) 1968;67:15–28. (In French) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ben Charfeddine I, Riepe FG, Kahloul N, Kulle AE, Adala L, Mamaï O, Amara A, Mili A, Amri F, Saad A, Holterhus PM, Gribaa M. Two novel CYP11B1 mutations in congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 11β hydroxylase deficiency in a Tunisian family. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2012;175:514–518. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choukair D, Beuschlein F, Zwermann O, Wudy SA, Haufe S, Holland-Cunz S, Bettendorf M. Virilization of a young girl caused by concomitant ectopic and intra-adrenal adenomas of the adrenal cortex. Horm Res Paediatr. 2013;79:318–322. doi: 10.1159/000350244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nakamura A, Schimizu C, Nagai S, Taniguchi S, Umetsu M, Atsumi T, Wada N, Yoshioka N, Ono Y, Sasano H, Koike T. Unilateral adrenalectomy improves insulin resistance and polycystic ovaries in a middle-aged woman with virilizing adrenocortical adenoma complicated with Cushing's syndrome. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30:65–69. doi: 10.1007/BF03347398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang S, Kamat A, Pergola P, Swamy A, Tio F, Cusi K. Metabolic factors in the development of hepatic steatosis and altered mitochondrial gene expression in vivo. Metabolism. 2011;60:1090–1099. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka S, Tanabe A, Aiba M, Hizuka N, Takano K, Zhang J, Young WF. Glucocorticoid- and androgen-secreting black adrenocortical adenomas, unique cause of corticotropin-independent Cushing syndrome. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:e73–e78. doi: 10.4158/EP.17.3.e73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordera F, Grant C, van Heerden J, Thompson G, Young W. Androgen-secreting adrenal tumors. Surgery. 2003;134:874–880. doi: 10.1016/S0039-6060(03)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lipsett MB, Hertz R, Ross GT. Clinical and pathophysiologic aspects of adrenocortical carcinoma. Am J Med. 1963;35:374–383. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(63)90179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fukushima DK, Gallagher TF. Steroid Production in ‘Nonfunctioning’ Adrenal Cortical Tumor: J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1963;23:923–927. doi: 10.1210/jcem-23-9-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim BY, Chun AR, Kim KJ, Jung CH, Kang SK, Mok JO, Kim CH. Clinical characteristics and metabolic features of patients with adrenal incidentalomas with or without subclinical Cushin's syndrome. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul) 2014;29:457–463. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2014.29.4.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, Bautista-Medina MA, Teniente-Sanchez AE, Zapata-Rivera MA, Montes-Villarreal J. Pure androgen-secreting adrenal adenoma associated with resistant hypertension. Case Rep Endocrinol. 2013;2013:356086. doi: 10.1155/2013/356086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petersons CJ, Burt MG. The utility of adrenal and ovarian venous sampling in the investigation of androgen-secreting tumours. Intern Med J. 2011;41:69–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2010.02375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nguyen PT, Lee RS, Conley AJ, Sneyd J, Soboleva TK. Variation in 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase activity and in pregnenolone supply rate can paradoxically alter androstenedione synthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012;128:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Groot JW, Links TP, Themmen AP, Looijenga LH, de Krijger RR, van Koetsveld PM, Hofland J, van den Berg G, Hofland LJ, Feelders RA. Aberrant expression of multiple hormone receptors in ACTH-independent macronodular adrenal hyperplasia causing Cushing's syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2010;163:293–299. doi: 10.1530/EJE-10-0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rask E, Schvarcz E, Hellman P, Hennings J, Karlsson FA, Rao CV. Adrenocorticotropin-independent Cushing's syndrome in pregnancy related to overexpression of adrenal luteinizing hormone/human chorionic gonadotropin receptors. J Endocrinol Invest. 2009;32:313–316. doi: 10.1007/BF03345718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morris LF, Park S, Daskivich T, Churchill BM, Rao CV, Lei Z, Martinez DS, Yeh MW. Virilization of a female infant by a maternal adrenocortical carcinoma. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:e26–e31. doi: 10.4158/EP10209.CR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fujieda K, Ito Y. Inactivating and activating mutations of the human LH/hCG receptor leading to male pseudohermaphroditism and familial male-limited precocious puberty. Nihon Rinsho. 2002;60:265–271. (In Japanese) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai KP, Huang CK, Fang LY, Izumi K, Lo CW, Wood R, Kindblom J, Yeh S, Chang C. Targeting stromal androgen receptor suppresses prolactin-driven benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) Mol Endocrinol. 2013;27:1617–1631. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mieritz MG, Sorensen K, Aksglaede L, Mouritsen A, Hagen CP, Hilsted L, Andersson AM, Juul A. Elevated serum IGF-I, but unaltered sex steroid levels, in healthy boys with pubertal gynaecomastia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2014;80:691–698. doi: 10.1111/cen.12323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monroe WE, Panciera D, Zimmerman KL. Concentrations of noncortisol adrenal steroids in response to ACTH in dogs with adrenal-dependent hyperadrenocorticism, pituitary-dependent hyperadrenocorticism, and nonadrenal illness. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26:945–952. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2012.00959.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]