Abstract

Modification of titanium dioxide (TiO2) for H2 generation is a grand challenge due to its high chemical inertness, large bandgap, narrow light-response range and rapid recombination of electrons and holes. Herein, we report a simple process to prepare nanospherical like reduced graphene oxide (NS-rGO) decorated TiO2 nanoparticles (NS-rGO/TiO2) as photocatalysts. This modified TiO2 sample exhibits remarkably significant improvement on visible light absorption, narrow band gap and efficient charge collection and separation. The photocatalytic H2 production rate of NS-rGO/TiO2 is high as 13996 μmol g−1 h−1, which exceeds that obtained on TiO2 alone and TiO2 with parallel graphene sheets by 3.45 and 3.05 times, respectively. This improvement is due to the presence of NS-rGO as an electron collector and transporter. The geometry of NS-rGO should be effective in the design of a graphene/TiO2 composite for photocatalytic applications.

The production of H2 by solar energy conversion has been considered as one of the major strategies for solving the global energy problem1. Since the first report by Fujishima and Honda2 on photoelectrochemical water splitting on a TiO2 electrode, the photocatalytic H2 production has attracted a lot of attention. Various semiconductor photocatalysts, such as TiO23,4, ZnO5,6, CdS7,8,9, C3N410,11,12, WO313, and BiVO414 have been investigated. Most of them suffer from wide band gap, photocorrosion, and low separation efficiency of electron-hole pairs3,4,5,6,7,8,9. Many efforts including doping, composites, noble metal loading, heterojunction fabrication and sensitization by dyes or quantum dots have been made to overcome these problems15,16. Among these, constructing nanocomposites is a promising approach to obtain high performance photocatalysts.

Graphene, a two-dimensional layer of sp2-hybridized carbon atoms, has been widely used in sensors, electronics, drug delivery, supercapacitors and catalysis due to its unique electrical properties17,18, high thermal conductivity19, mechanical strength and specific surface area20. To date, a variety of reduced graphene oxide (rGO) based semiconductor photocatalysts (e.g., TiO2, CdS, BiVO4 and C3N4) have been reported21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Nanocomposite is currently one of the most interesting subjects for photocatalytic, especially graphene/nano-TiO2 composites28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. Although the role of rGO for photocatalytic performance has been extensively investigated, the complexity of the rGO structure, including hybridized atoms, various functional groups, and defects makes it difficult to well understand some electrical and optical properties, and thus some new explorations in developing highly efficient photocatalysts have been hampered. The introduction of graphene can enhance photocatalytic the performance because both specific reaction sites and photoresponding range are improved7. This work confirm that the pathway of electrons collection and separation may also be a key factor in the photocatalytic performance but until now it has completely been ignored. The material properties are strongly dependent on their size, shape and, equally important, structures39. Nanostructure with controllable morphology not only facilitate mass transfer in catalysis, but more importantly can assist to guide charge movement to accelerate the collection and separation of electron-hole pairs at materials interface for efficient utilization of solar energy to drive relevant reactions10. As far as we are aware, few attempt has been made to synthesize nanospherical reduced graphene oxide (NS-rGO), and hence, its unique photocatalytic activity is almost completely unknown40,41,42,43. Herein, we synthesized the NS-rGO decorated TiO2 nanoparticle through the core shell method followed by mixing. This method is interesting for the preparation of NS-rGO decorated TiO2 nanoparticle. The photocatalytic H2 production rate of NS-rGO/TiO2 is enhanced than that obtained on TiO2 alone and TiO2 with parallel graphene sheets by 3.45 and 3.05 times, respectively.

Results

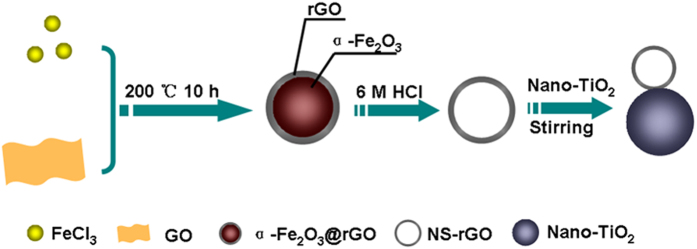

In line with the intensive research on layer graphene and carbon nanosphericals, we report here for the first time an approach for the facile preparation of NS-rGO decorated TiO2 heterojunction materials. The morphology and structure of α-Fe2O3@rGO were characterized by SEM and TEM. As illustrated in Fig. 1, core-shell α-Fe2O3@rGO (Figures S1 and S3) with monodisperse and well-defined graphene shell40 is an ideal template to prepare NS-rGO. According to the result in Fig. S1b, the structure of the prepared α-Fe2O3@rGO was between sphere and ellipse. The Figures S2a,b respectively showed the SEM and TEM images of α-Fe2O3@rGO, which further supporting our judgment. After the removal of α-Fe2O3 by HCl, spherical like NS-rGO with lofted surface was observed in Figure S4, because NS-rGO was prepared by acidic etching. The nanosized NS-rGO with spherical like morphology is used for decorating TiO2 nanoparticles. The strong interfacial interaction between positively charged NS-rGO and negatively charged TiO2 nanoparticals can extend photoresponding range and suppress photogenerated carriers’ recombination. The NS-rGO decorated TiO2 nanocomposites exhibit much higher photocatalytic activities for water splitting into H2 than layer rGO decorated TiO2 nanocomposites. This work may provide new insights into the fabrication of graphene based nanocomposite photocatalysts for various applications.

Figure 1. Illustration of NS-rGO/TiO2 synthesis.

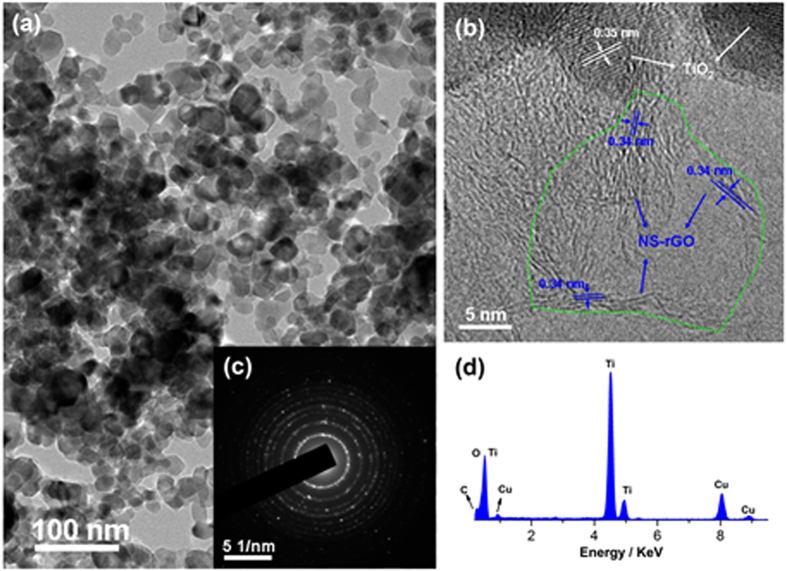

In a typical experiment, with a mass ratio of 100:1, TiO2 and NS-rGO were mixed at room temperature (about 20 °C), resulting in a gray suspension. TEM was employed to observe its morphology. Figure 2a clearly showed that these nanocomposites were sphere structure with nanosize, and no large reduced graphene oxide layer could be seen. Figure 2b taken from the interfacial region indicated that NS-rGO was loaded onto TiO2 nanoparticles and the interplanar distance of TiO2 and NS-rGO in the crystalline network was 0.35 nm and 0.34 nm, respectively. Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern taken from nanocomposites showed the multi-crystalline nature of nanoparticles (Fig. 2c). In addition, energy dispersive X-ray spectrum (EDX) of the NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocomposites (Fig. 2d) showed the existence of three elements, Ti, O, and C. For rGO/TiO2 nanocomposites, Figure S5a clearly showed that the nanocomposites of rGO sheet and TiO2 nanoparticles, the sheet structure of rGO was observed in blue line area, indicated forming composite structure among them. Figure S5b clearly showed that the Pt nanoparticles were uniform deposited on the surface of NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocompositions.

Figure 2.

Typical TEM (a) and HRTEM (b) images of NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocompositions, the corresponding SAED pattern (c) and EDX pattern (d).

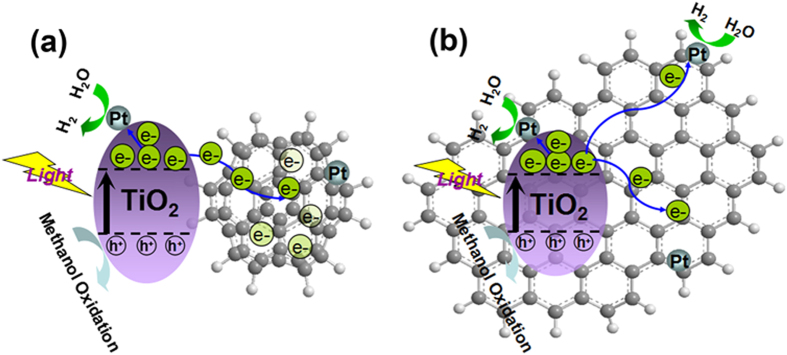

XRD pattern (Fig. 3) was recorded for bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2, or NS-rGO/TiO2 to confirm and investigate the influence of introduction materials on the crystallinity of TiO2 nanoparticles. rGO/TiO2 nanocompositions were synthesized for the comparation with NS-rGO/TiO2 in the subsequent section. For TiO2, one could see that rutile and anatase were mixed. The nanocomposites of rGO/TiO2, and NS-rGO/TiO2 with a same and low carbon content exhibited anatase and rutile phases from TiO2. Due to very little of graphene introduction, no peaks corresponding to the presence of graphite latticewere recorded in the pattern. The results implied that the existence of graphene materials did not change the crystal phase of TiO2.

Figure 3. XRD patterns for as-prepared TiO2, rGO/TiO2, and NS-rGO/TiO2.

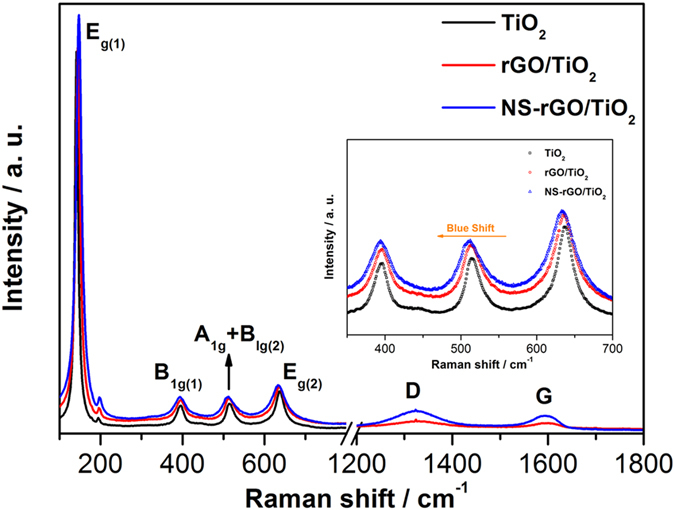

To clarify this issue further, raman analysis was performedand shown in Fig. 4. The characteristic peaks of bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 composites were observed at about 141, 396, 514, and 637 cm−1, corresponding to the Eg(1), B1g(1), A1g + B1g(2), and Eg(2) modes of anatase, respectively27. Also, the observed B1g(1), A1g + B1g(2), and Eg(2) peaks of the rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 composites were slightly shifted in comparison with the bare TiO2, indicated the formation of hybrid structure between NS-rGO and TiO2 nanoparticles. Significantly, two peaks at about 1356 and 1596 cm−1, which were corresponded to the well-defined D and G bands for the graphitized structures, respectively, were also observed. This result confirmed the presence of reduced graphene oxide in the rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 composites. The intensity ratio of the D and G bands (ID/IG) of rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocompositions was respectively 1.18 and 1.24, which indicated that the difference in micro-structures and NS-rGO had fewer defects than rGO. Compared to the ID/IG of GO (0.96), the ID/IG of rGO was increased, which indicated that GO could be reduced with hydrothermal reaction. This increase might be caused by structural defects within the sp2 carbon network that arose upon the reduction of the exfoliated GO.

Figure 4. Raman spectra of TiO2, rGO/TiO2, and NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocompositions.

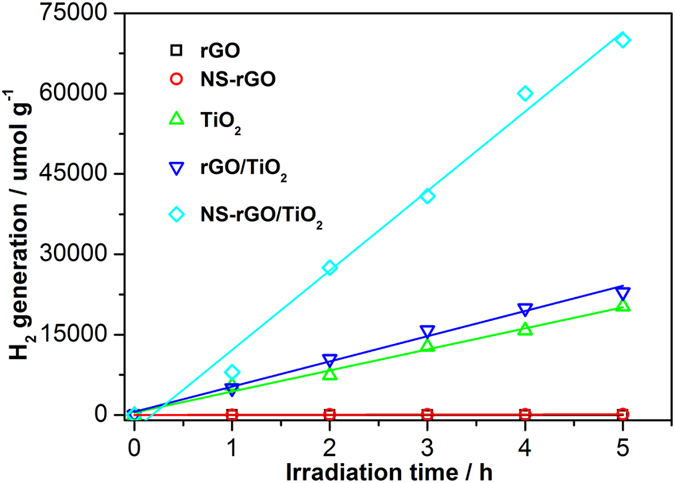

In this work, the photocatalytic H2 production activity of the prepared rGO, NS-rGO, TiO2, rGO/TiO2, and NS-rGO/TiO2 samples was evaluated under UV-Vis irradiation using methanol and Pt as sacrificial reagent and co-catalyst, respectively. As shown in Fig. 5, graphene exhibited a significant influence on the photocatalytic activity. Compared to bare TiO2, the enhancement of photocatalytic activity for rGO/TiO2 (3.05 times) and NS-rGO/TiO2 (3.45 times) composites was observed. For TiO2 alone, a relatively low photocatalytic H2 production rate (4053 μmol g−1 h−1) was obtained due to its rapid recombination of conduction band electrons and valence band holes. Controlled experiments used rGO and NS-rGO as catalyst at the same conditions, graphene materials showed no significant photocatalytic activity for H2 production. The photocatalytic H2 production rate of hybrid materials were significantly greater than that of either TiO2 or graphene materials. The NS-rGO/TiO2 had a higher H2 production rate (13996 μmol g−1 h−1) than rGO/TiO2 (4588 μmol g−1 h−1) and TiO2 (4053 μmol g−1 h−1)in the five hours. The compared the rate of hydrogen evolution with the activities obtained in similar systems in previous investigations are influenced by different experimental conditions (i. e., catalyst concentration, light intensity). Therefore, the accurate comparison between other materials is very difficult.

Figure 5. Reaction time profiles of hydrogen production under UV-Vis light illumination over TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 compositions for comparsion.

(reaction conditions: light source, 300 W Xe arc lamp; catalyst, 50 mg; methanol aqueous solution, 20% v/v 80 mL.) All data at least 3 times reproduced measurements.

Discussion

The introduction of carbon materials (e.g., fullerene44, carbon dots45, carbon nanotubes46, graphene oxide and graphene sheets21,24) into semiconductor could significantly enhance photocatalytic activity. The enhancement mechanism could be attributed to carbon materials, which could (1) offer more active adsorption sites and photocatalytic reaction centers, (2) suppress the recombination of the photogenerated electron/hole pairs, (3) prolong the lifetime of electrons and holes, (4) narrow the band gap of photocatalyst, and (5) act as photosensitizer or cocatalyst for catalytic reaction.

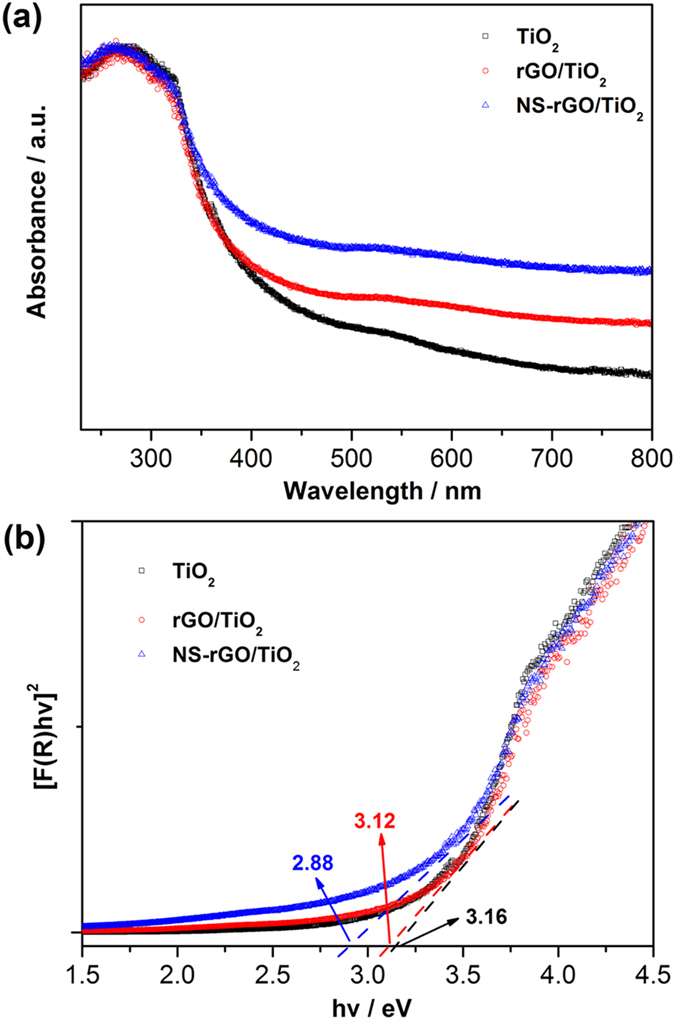

UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra (DRS) were used to probe the optical properties of the bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 composites. According to Fig. 6a, the light absorbance of rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocomposites was extended into the visible regime (>450 nm), which was in faithful agreement with the color of the samples (i.e., white for bare TiO2, french grey for rGO/TiO2 and dark gray for NS-rGO/TiO2). The red shift and the improved light absorption for rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 could be attributed to the introduction of graphene, XPS and FTIR showed no Ti-O-C species in compositions (Figure S6). A plot obtained via the transformation based on Kubelka-Munk function versus energy of light was shown in Fig. 6b. The estimated bandgaps of the samples were 3.16, 3.12, and 2.88 eV, corresponding to bare TiO2, hybrid materials with rGO and NS-rGO, respectively. This results indicated a bandgap narrowing of TiO2 integrated with rGO or NS-rGO by the interfacial interaction. Because of light absorbance increase and bandgap narrowing, a more efficient utilization of light could be obtained.

Figure 6.

(a) UV-vis absorption spectra of bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2. (b) Plot of transformed Kubelka-Munk function (F(R)hv)1/2 versus energy of light (hv) for bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2.

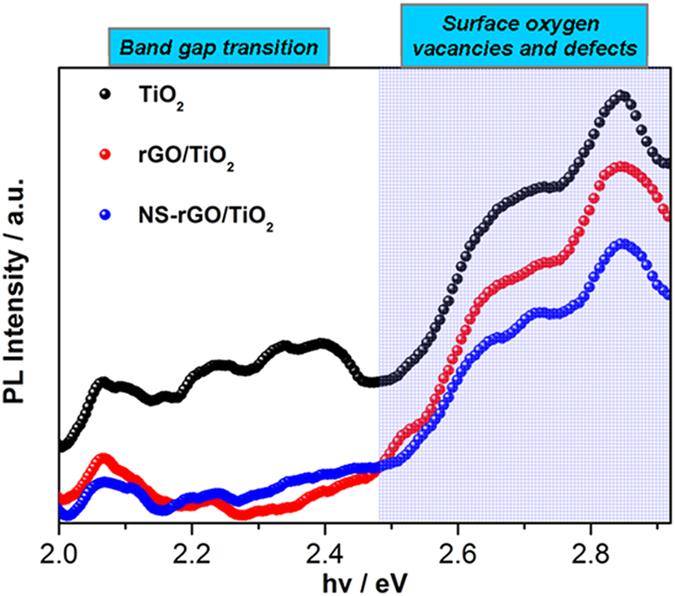

To further understand the transfer and recombination processes of photoexcited charge carriers in these samples, PL spectra of bareTiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2, which could be employed to investigate the fate of electron-hole pairs in semiconductor successfully47,48, were also measured and shown in Fig. 7. As could be seen from this figure, TiO2, with mixture phases, was characterized by three main peaks (around 2.4, 2.72, 2.85 eV) and lots of small peaks, which attributed to band gap transition and surface oxygen vacancies and defects44. The composite of graphene with TiO2 could influence its PL spectrum. But the main emission of origin materials were not changed. Obviously, in comparison to bare TiO2, the intensity of PL signal for the rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocomposites was much lower. This indicated the photogenerated electrons from TiO2 was transferred into carbon atoms on the graphene, then the charge recombination was reduced, while NS-rGO was more efficient for surface oxygen vacancies and defects. This further verified that the NS-rGO decorated TiO2 was more beneficial than rGO for the electron/hole separation.

Figure 7. PL spectra of bare TiO2, rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 (with the excitation wavelength of 315 nm).

TiO2 and rGO (or NS-rGO) were mixed with a mass ratio of 100:1 at room temperature, resulting in rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2, respectively. The concentration of graphene in the prepared rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 was also characterized by TGA (Figure S7). The total weight loss of rGO/TiO2 (4.67%) or NS-rGO/TiO2 (0.92%) could be ascribed to the loss of the adsorbed H2O, the crystal transfer of TiO2 and the oxidation of rGO or NS-rGO. From the TGA results, the real content of rGO or NS-rGO in the nanocomposite could not be estimated , but low concentration of graphene was confirmed which was consistent with the dosage of theory (100:1 of TiO2 : rGO/NS-rGO). The BET was also added, and the high surface area and porous structure might be the reason for the high activity of NS-rGO/TiO2. Because the BET surface area of rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 was 53.2 m2/g and 54.2 m2/g, respectively, and their pore distribution was also similar (Figure S8), the comparison between NS-rGO/TiO2 and rGO/TiO2 could be used to disclose the influence of graphene structure on the photocatalytic H2 production activity.

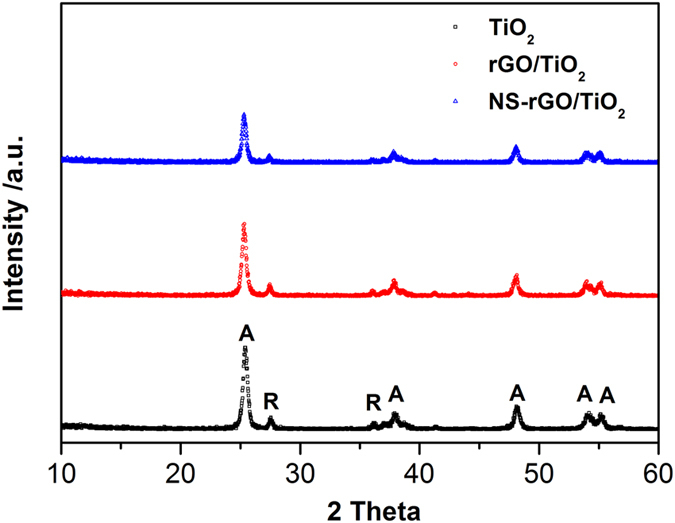

On the basis of the above results, a tentative mechanism of the photocatalytic reaction was proposed as illustrated in Fig. 8. When irradiated under visible light, the electron/hole (e−/h+) pairs from TiO2 were excited and formed. The electrons were most likely to transfer in one of three following ways to: (1) Pt deposited on the surface of TiO2 nanoparticles; (2) carbon atoms on the graphene; or (3) Pt located on the graphene7. Eventually, the electrons were reacted with the adsorbed H+ ions for H2 production. This mechanism almost faultlessly explained why rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 could significantly enhance photocatalytic activity. With the increasing of irradiation time from 1 h–5 h, the photocatalytic H2 production rate of NS-rGO/TiO2 was three times higher than rGO/TiO2. In this regard, when electrons were transferred to carbon atoms on the graphene, the flat structure of rGO could help electrons freely travel all around and then the opportunity for electrons/holes recombination was enough (Fig. 8a). While the sphere structure of NS-rGO contained multilayer graphene sheets was used, electrons not only could freely travel on the graphene sheets like as rGO, but also transfer from outer graphene sheets to inner sheets. It might be noticed that the inner electrons were tentatively stored and almost no chance to be reacted. This could be explained as electrons warehouse in the NS-rGO (Fig. 8b). Once NS-rGO was introduced to the TiO2 to form hybrid catalyst, it could efficiently suppress charge recombination, improve interfacial charge transfer, furthermore, the unique feature of NS-rGO could provide more active adsorption sites, photocatalytic reaction centers and reaction space than that of rGO. As a consequence, a suitable structure of graphene was crucial for providing the photocatalytic activity and stability of graphene based photocatalysts.

Figure 8.

Illustration of the working principle of (a) NS-rGO/TiO2 (b) rGO/TiO2 and photocatalytic system for hydrogen production under UV-Vis irradiation.

Methods

Materials

Graphite powder was purchased from national medicine group chemical reagent Co., Ltd. in China. Sodium nitrate, potassium permanganate, hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid, barium chloride, and hydrogen peroxide (30%) were analytical grade and purchased from Shantou west long chemical Co., Ltd in China. Iron (III) chloride anhydrous (98%) was purchased from Alfa Aesar. Nano-TiO2 nanoparticles were purchased from Alfa Aesar. All chemicals and solvents were used as received. All aqueous solutions were prepared using ultrapure water (18 MU) from a Milli-Q system (Millipore).

Instrumentation

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was conducted by a Tecnai G2 20 S-TWIN.TEM instrument was operated at 200 kV. Scanning electron microscope (SEM) imaging and EDX chemical analysis were conducted using a JSM-6010La scanning electron microscope. Using Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 0.1541 nm), the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of all samples were recorded with a D/MAX in Japan-TTRIII diffractometer and the data were collected from 10° to 80° (2 Theta). UV-vis diffuse reflectance spectra were measured on a Hitachi spectrophotometer using BaSO4 as a reference. Band gap energies were calculated by analysis of the Tauc-plots resulting from Kubelka-Munk transformation of diffuse reflectance spectra, which can be estimated from the intersection point of the linear part of the plot (F(R)·hv)1/2 versus hv with the photon energy axis. The fluorescence (FL) measurements were performed on a Hitachi U-3010 spectrophotometer at room temperature.The excitation wavelength was 315 nm. Raman spectrum was performed by using a laser raman spectrometer (LabRAM HR800) at room temperature. The Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method was utilized to calculate the specific surface areas (SBET). Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a NETZSCH TG 209 F1 thermogravimetric analyzer from room temperature to 800 oC with a heating rate of 10 oC min−1 and an N2 flow rate of 20 mL min−1.

Preparation of graphene oxide

Graphene oxide (GO) was prepared according to a modified Hummer method32. Typically, graphite powder (1.0 g) was mixed with concentrated sulfuric acid (23 mL) in a 1 L round bottom flask and stirred in an ice bath. NaNO3 (0.5 g) and KMnO4 (3.0 g) were slowly added into the suspension and kept the temperature at 0 ± 1 °C. After keeping the mixture at 35 ± 3 °C for 30 min, water (46 mL) was slowly added, the suspension was heated up to 98 °C and maintained for 15 min, and then 140 mL of water and 2 mL of H2O2 (30%) were added to end the reaction. Thereafter, the suspension was hot filtered, washed by HCl solution (5%) until no SO42− could be detected in the filtrate, the products were vacuum-dried at 60 °C over-night and then sealed for the preservation.

Preparation of NS-rGO and rGO

NS-rGO was prepared by a simple two-step reaction. Reduced graphene oxide coated α-Fe2O3 nanopellets were prepared as follows. Ferric chloride (1.0 g) and anhydrous sodium acetate (1.0 g) were dissolved in diethylene glycol (20 mL) and then graphene oxide solution (5.0 mg mL−1, 5 mL) was added. The mixture was dispersed by ultrasound for 30 min, transferred into a teflonlined stainless-steel autoclave, heated to and maintained at 200 °C for 10 h, and then cooled to room temperature. The black products were washed several times with ethanol and water. The brownish red solid was obtained and dried at 80 °C. Hydrochloric acid (6 mol L−1, 30 mL) was added into above mentioned solid, keeping for one day. After that, the mixture was filtered with 0.22 μm filter membrane, and washed by ultrabare water until the filtrate was neutral. The black and feathery solid was dried at 80 °C and then NS-rGO was obtained. rGO was prepared similar to NS-rGO except that no Ferric chloride was added.

Preparation of photocatalyst (rGO/TiO2, NS-rGO/TiO2, Pt-TiO2, Pt-rGO/TiO2 and Pt-NS-rGO/TiO2)

The hybrid photocatalysts were synthesized by directly mixing. TiO2 (0.5 g) was dissolved in 20 mL of ethanol with stirring. Then, rGO or NS-rGO (5 mg) was mixed with TiO2-ethanol solution by ultrasonic for 1 h at room temperature. After that the samples were dried in an air oven at 80 °C for 24 h and then rGO/TiO2 and NS-rGO/TiO2 nanocomposites were obtained, respectively. In order to synthesize Pt-rGO/TiO2 and Pt-NS-rGO/TiO2, the photocatalytic deposition method was carried out in the presence of nanocomposites (rGO/TiO2 or NS-rGO/TiO2) and chloroplatinic acid (H2PtCl6) in methanol solution (1 mol L−1). The platinum deposition was achieved under UV irradiation for 30 min using a 200-W mercury lamp. The amount of platinum was fixed at 0.1 wt % among TiO2, rGO/TiO2, or NS-rGO/TiO2.

Photocatalytic reaction

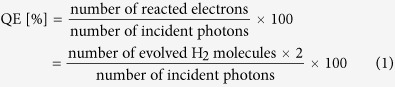

Water splitting reactions were carried out in a Pyrex vessel connected to a glass closed circulation and evacuation system. The light source was a 300 W Xe arc lamp (Perfectlight Co., PLS-SXE300). Prior to irradiation, the whole system, including the photocatalysts was purged with argon at 100 N mL/min to remove the air completely. High-purity Argon (99.9999%) was used as a carrier gas for the reaction products of which continuous gas flow was set to 50 N mL min−1. Gas chromatography equipped with a thermal conductivity detector and molecular sieve 5-Å column with Ar carrier gas was used for the determination of hydrogen concentration. In a typical run, 50 mg of photocatalyst powder was suspended in an 80 mL, 20% v/v methanol aqueous solution. Here, platinum and methanol were added as co-catalyst and sacrificial reagent, respectively. The apparent quantum efficiency (QE) was measured under the same photocatalytic reaction condition with four 365 nm-LEDs used as light sources to trigger the photocatalytic reaction, and the QE was calculated according to equation (1)

|

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Chen, D. et al. Nanospherical like reduced graphene oxide decorated TiO2 nanoparticles: an advanced catalyst for the hydrogen evolution reaction. Sci. Rep. 6, 20335; doi: 10.1038/srep20335 (2016).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 20775067, 20977074, 21175115 and 21475055), the Science & Technology Committee of Fujian Province, China (No. 2012Y0065), and the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (NCET-11 0904).

Footnotes

Author Contributions D.C. and S.L. wrote the main manuscript text. L.Z., D.C. and F.Z. performed the experiments and prepared Figures 2–7. F.Z. prepared Figure 1. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Paracchino A. et al. Highly active oxide photocathode for photoelectrochemical water reduction. Nat. Mater. 10, 456–461 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujishima A. et al. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 238, 37–38 (1972). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. et al. Water-soluble and lowly toxic sulphur quantum dots. Adv. Funct. Mater. 45, 7133–7138 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Zuo F. et al. Active facets on titanium (III)-doped TiO2: an effective strategy to improve the visible-light photocatalytic activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 124, 6327–6330 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. et al. Efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution over hydrogenated ZnO nanorod arrays. Chem. Commun. 48, 7717–7719 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P. et al. The synergetic effect of sulfonated graphene and silver as co-catalysts for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production of ZnO nanorods. J. Mater. Chem. A 1, 14262–14269 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Li Q. et al. Highly efficient visible-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen production of CdS-cluster-decorated graphene nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 10878–10884 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao N. et al. Self-templated synthesis of nanoporous CdS nanostructures for highly efficient photocatalytic hydrogen production under visible light. Chem. Mater. 20, 110–117 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. Synthesis of CdS nanorods by an ethylenediamine assisted hydrothermal method for photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C 113, 9352–9358 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J. et al. Nanospherical carbon nitride frameworks with sharp edges accelerating charge collection and separation at a soft photocatalytic interface. Adv. Mater. 26, 4121–4126 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. et al. Highly efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution from water using visible light and structure-controlled graphitic carbon nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 9240–9245 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. et al. A metal-free polymeric photocatalyst for hydrogen production from water under visible light. Nat. Mater. 8, 76–80 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashi M. et al. Photocatalytic overall water splitting under visible light using ATaO2N (A = Ca, Sr, Ba) and WO3 in a IO3−/I− shuttle redox mediated system. Chem. Mater. 21, 1543–1549 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Jia Q. et al. Facile fabrication of an efficient BiVO4 thin film electrode for water splitting under visible light irradiation. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 11564–11569 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamegawa T. et al. A visible-light-harvesting assembly with a sulfocalixarene linker between dyes and a Pt-TiO2 photocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 916–919 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X. et al. Semiconductor-based photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Chem. Rev. 110, 6503–6570 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. et al. Chemically derived graphene oxide: towards large-area thin-film electronics and optoelectronics. Adv. Mater. 22, 2392–2415 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C. et al. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 321, 385–388 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balandin A. et al. Superior thermal conductivity of single-layer graphene. Nano Lett. 8, 902–907 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. et al. Graphene and graphene oxide: synthesis, properties, and applications. Adv. Mater. 22, 3906–3924 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q. et al. Synergetic effect of MoS2 and graphene as cocatalysts for enhanced photocatalytic H2 production activity of TiO2 nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 6575–6578 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W. et al. Nanocomposites of TiO2 and reduced graphene oxide as efficient photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution. J. Phys. Chem. C 115, 10694–10701 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q. et al. Graphene-based semiconductor photocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 782–796 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X. et al. Graphene/TiO2 nanocomposites: synthesis, characterization and application in hydrogen evolution from water photocatalytic splitting. J. Mater. Chem. 20, 2801–2806 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Iwase A. et al. Reduced graphene oxide as a solid-state electron mediator in Z-scheme photocatalytic water splitting under visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11054–11057 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. et al. Electrostatic self-assembly of BiVO4-reduced graphene oxide nanocomposites for highly efficient visible light photocatalytic activities. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 6, 12698–12706 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q. et al. Enhanced photocatalytic H2-production activity of graphene-modified titania nanosheets. Nanoscale 3, 3670–3678 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan W. et al. Fabrication of TiO2/RGO/Cu2O heterostructure for photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 181, 7–15 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- Moon G. H. et al. Solar production of H2O2 on reduced graphene oxide-TiO2 hybrid photocatalysts consisting of earth-abundant elements only. Energy Environ. Sci. 7, 4023–4028 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Mou Z. et al. TiO2 Nanoparticles-functionalized N-doped graphene with superior interfacial contact and enhanced charge separation for photocatalytic hydrogen generation. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 6, 13798–13806 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon G. et al. Platinum-like behavior of reduced graphene oxide as a cocatalyst on TiO2 for the efficient photocatalytic oxidation of arsenite. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 1, 185–190 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wang C. et al. Enhanced photo-electrocatalytic performance of Pt/RGO/TiO2 on carbon fiber towards methanol oxidation in alkaline media. J. Solid State Electr. 18, 515–522 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q. et al. Graphene-based photocatalysts for solar fuel generation, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 11350–11366 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Q. et al. Graphene-based photocatalysts for hydrogen generation, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 753–759 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L. et al. Engineering the TiO2-graphene interface to enhance photocatalytic H2 production. ChemSusChem. 7, 618–626 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing M. et al. Synergistic effect on the visible light activity of Ti3+ doped TiO2 nanorods/boron doped graphene composite. Sci. Rep. 4 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. et al. Synthesis and photocatalytic activity of graphene based doped TiO2 nanocomposites, Appl. Surf. Sci. 319, 8–15 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. A hydrothermal route for constructing reduced graphene oxide/TiO2 nanocomposites: Enhanced photocatalytic activity for hydrogen evolution, Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 39, 19877–19886 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Nai J. et al. Structure-dependent electrocatalysis of Ni[OH]2 hourglass-like nanostructures towards L-histidine. Chem. -Eur. J. 19, 501–508 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y. et al. Facile fabrication of reduced graphene oxide encapsulated copper spherical particles with 3D architecture and high oxidation resistance. RSC Adv. 4, 58005–58010 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chen D. et al. Unique lead adsorption behavior of ions sieves in pellet-like reduced graphene oxide. RSC Adv. 5, 73333–73339 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudian M. et al. Synthesis and characterization of Fe3O4 rose like and spherical/reduced graphene oxide nanosheet composites for lead (II) sensor. Electrochim. Acta 169, 126–133 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Li S. et al. Yolk-shell hybrid nanoparticles with magnetic and pH-sensitive properties for controlled anticancer drug delivery. Nanoscale 5, 11718–11724 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai B. et al. Synthesis of C60-decorated SWCNTs (C60-d-CNTs) and its TiO2-based nanocomposite with enhanced photocatalytic activity for hydrogen production. Dalton Trans. 42, 3402–3409 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. et al. Water-soluble fluorescent carbon quantum dots and photocatalyst design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 4430–4434 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W. et al. Record high hole mobility in polymer semiconductors via side-chain engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 14896–14899 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang J. et al. Photophysical and photocatalytic properties of AgInW2O8. J. Phys. Chem. B 107, 14265–14269 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Eda G. et al. Blue photoluminescence from chemically derived graphene oxide. Adv. Mater. 22, 505–509 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.