Abstract

During the past decade, unmet need for family planning has remained high in Pakistan and gains in contraceptive prevalence have been small. Drawing upon data from a 2012 national study on postabortion-care complications and a methodology developed by the Guttmacher Institute for estimating abortion incidence, we estimate that there were 2.2 million abortions in Pakistan in 2012, an annual abortion rate of 50 per 1,000 women. A previous study estimated an abortion rate of 27 per 1,000 women in 2002. After taking into consideration the earlier study’s underestimation of abortion incidence, we conclude that the abortion rate has likely increased substantially between 2002 and 2012. Varying contraceptive-use patterns and abortion rates are found among the provinces, with higher abortion rates in Baluchistan and Sindh than in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Punjab. This suggests that strategies for coping with the otherwise uniformly high unintended pregnancy rates will differ among provinces. The need for an accelerated and fortified family planning program is greater than ever, as is the need to implement strategies to improve the quality and coverage of postabortion services.

Pakistan, the world’s sixth most populous country, has a record of slow fertility decline compared with other Asian countries. Although the total fertility rate declined from about 6.0 children per woman in the early 1980s to 3.8 in 2010–12, the rate of decrease has been slow and the TFR remains moderately high (NIPS and Macro International 2008; NIPS and ICF International 2013). In addition, actual average family size is one child more than desired family size, and this differential has changed little over the past decade. The increase in contraceptive use has also been slow over the past decade, rising from 28 percent in 2001–03 (NIPS 2001) to 35 percent in 2012–13 (NIPS and ICF International 2013). Less effective traditional methods are used by a substantial proportion of current users (26 percent), and discontinuation of method use is high (37 percent of all contraceptive use was discontinued in less than one year) (NIPS and ICF International 2013). The high level of unwanted child-bearing and the slow increase in contraceptive use are reflected in a substantial unmet need for contraception, estimated at 20 percent in 2012–13 (NIPS and Macro International 2008; Bradley et al. 2012; NIPS and ICF International 2013). These factors place a large proportion of currently married women at risk of unwanted pregnancy (NIPS and ICF International 2013).

Research in Pakistan and South Asia more generally indicates that couples who experience mistimed or unwanted pregnancies are likely to resort to induced abortion (Caldwell et al. 1999; Ganatra and Hirve 2002; Dhillon et al. 2004; Kamran, Arif, and Vasses 2011). According to a study conducted in Karachi, some 88 percent of pregnancies ending in induced abortion resulted from unwanted pregnancies or contraceptive failure (Gazdar, Khan, and Qureshi 2012). Health professionals surveyed in a national study stated that the majority of women seeking abortions had been using a method of birth control at the time of the unwanted pregnancy, implying that contraceptive methods had been incorrectly or inconsistently used (Rashida et al. 2003). Saleem and Fikree (2001) found that women in low-socioeconomic settlements in Karachi often opted for abortion rather than using modern contraception to attain their goal of small family size. The majority of couples who sought an abortion had four or more children (Fikree et al. 1996; Saleem and Fikree 2001; Bhutta, Aziz, and Korejo 2003; Population Council 2004; Khan 2013).

A national study on abortion in Pakistan (Population Council 2004) estimated that 890,000 induced abortions were performed in 2002, and many small community-based studies corroborate this widespread practice of abortion (Mahmud and Mushtaq 2001; Saleem and Fikree 2001; Khan 2009 and 2013; Vlassoff, Singh, and Suarez 2009). This is so despite legal restrictions on abortion in Pakistan. In 1990, the law was relaxed to permit abortion to save the mother’s life or to provide “necessary treatment” (Government of Pakistan 1990; Rahman, Katzive, and Henshaw 1998; UNPD 2002). Legal restrictions and religious beliefs clearly have little influence once the decision to have an abortion is made (Bhutta, Aziz, and Korejo 2003). Legal barriers do, however, lead to a higher incidence of unsafe abortions (WHO 2012b), because health clinics cannot openly provide abortion services and most women seek help from unqualified providers and/or use traditional methods. Although small-scale studies on this topic have been conducted in Pakistan, they have mostly taken place in Punjab and Sindh provinces and do not fully represent the diverse conditions in the country (Khan 2013).

Health risks associated with unsafe abortion are well established (Gilani and Azeem 2005; Saleem and Fikree 2005; Madhu Das and Srichand 2006; Rahman et al. 2007; Siddique and Hafeez 2007; Gazdar, Khan, and Qureshi 2012), especially in countries like Pakistan where legal and safe abortion services are generally unavailable. Gazdar, Khan, and Qureshi (2012) found that the majority of postabortion complications in Pakistan arose when abortions were sought from untrained midwives or administered by the women themselves. In the developing world, including Pakistan, morbidity and mortality associated with unsafe abortion exert an enormous health, financial, and social burden on women and on the health care system as a whole (WHO 2003, 2011; Singh 2006; Shaikh et al. 2010). Lack of appropriate postabortion care can lead to lifelong morbidity, contribute to maternal mortality, and adversely affect the health of future children (Dhillon et al. 2004; Badshah et al. 2008; Rahman, DaVanzo, and Razzaque 2010; Shaikh et al. 2010; Ahman and Shah 2011; WHO 2011).

Over the past few decades, the provision of health care by the private sector in Pakistan has increased as the public sector’s role has diminished. The quality of service provided at public health care facilities has been poor, in part because of increased demand for services by a rapidly growing population. This has allowed the private sector (which provides better quality of care) to step in and become the leading source of outpatient consultations and maternal and child health services, despite their high cost (World Bank 2010; Afzal and Yusuf 2013). This trend toward the private sector is also reflected in the provision of postabortion care, where an estimated 62 percent of women were treated by private-sector providers in 2012 (Sathar et al. 2013). Increasing urbanization is also likely linked to increased access to private health care services in general, including providers of abortion services.

NEW ESTIMATES OF ABORTION INCIDENCE AND RELATED MORBIDITY

No new national-level studies have been conducted in Pakistan to estimate the incidence of abortion and abortion-related morbidity since 2002 (Sathar, Singh, and Sadiq 2007). In light of the recent devolution of power from federal to provincial levels, the country’s provincial health and population welfare departments have been empowered to develop their own policies and programs based on local circumstances and available evidence. There is, therefore, a need to provide provincial governments with updated information and estimates of the magnitude of abortion and unintended pregnancy. This information is essential in helping policymakers respond to the need both for expanded contraceptive services to reduce unintended pregnancies and for improved postabortion-care services to reduce abortion-related morbidity and mortality.

This study presents new estimates of the incidence of induced abortion in Pakistan for the year 2012, at both the national and provincial levels. The incidence of induced abortion in 2002 and 2012 is analyzed to assess the change in the total number and rate of abortions performed, the annual abortion rate, the abortion ratio, and the number and rate of women treated in health facilities for postabortion care. Changes in the magnitude of facility-based treatment for complications from unsafe abortions are also analyzed. The methodology used to collect data and estimate abortion incidence in 2012 is the same as was used for the 2002 estimates (Sathar, Singh, and Fikree 2007). The 2012 study is more comprehensive, however, because it includes both the private and public sectors, whereas the 2002 study included only public-sector estimates. This difference in inclusion of health facilities has been taken into account in assessing changes over time.

DATA SOURCES AND METHODOLOGY

Our study was based on the earlier 2002 study (Sathar et al. 2007) and uses an indirect estimation technique that has been peer reviewed and employed in countries around the world (Singh, Remez, and Tartaglione 2010). The methodology is based on estimates of the number of women who had postabortion complications and were treated in health facilities, and is combined with other information to estimate the number and rate of induced abortions (Singh, Remez, and Tartaglione 2010). Three data sources were used: the Health Facilities Survey, the Health Professionals Survey, and supplementary data sources that include the Pakistan Demographic and Health Surveys, the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey, and the GIS Census of Health facilities.

Health Facilities Survey

The Health Facilities Survey (HFS) is the primary source of data for estimating the incidence of abortion in Pakistan. The HFS was conducted in 2012 among a nationally representative sample of all public and private health facilities likely to be treating patients for postabortion complications. The survey, conducted in the four major provinces (Baluchistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa [KP], Punjab, and Sindh), included all large public and private teaching hospitals; a sample of public-sector tertiary facilities (i.e., District Headquarter Hospitals [DHQs] that usually have 80 or more beds, Tehsil Headquarter Hospitals [THQs] that have 20–79 beds, and Rural Health Centers [RHCs] that have 5–19 beds); and a sample of private-sector health facilities similar to the three types of public-sector facilities based on bed size. The primary aim of the HFS was to estimate the number of women being treated for postabortion complications nationally, for each province, and by type of facility, and to assess the capacity and quality of provision of postabortion-care services.1 Using a stratified two-stage sampling design, districts were selected and facilities were then selected within sampled districts.

Sampling of Districts

Within each of the four major provinces, districts were first ordered according to the proportion of the population below the poverty level (Jamal 2007). Districts were then selected from each province, ensuring representation of the range of the percent poor within a province. Ten districts were selected in Punjab, eight in Sindh, three in KP, and three in Baluchistan. The availability of comprehensive listings of private-sector facilities through GIS mapping was one criterion in district selection. Where a district that was contiguous to a randomly selected district had a similar poverty ranking, the district with the GIS maps was selected. Additional mapping was conducted to complete the listings of private-sector facilities in four sampled districts not covered by GIS mapping, for which no equivalent lists of private-sector facilities were available. Finally, a few districts were excluded from the selection in KP province because of security concerns at the time of the fieldwork. The 24 districts covered by the HFS contain 35 percent of Pakistan’s total population. The population of the 24 districts was distributed across provinces as follows: 52 percent in Punjab, 34 percent in Sindh, 11 percent in KP, and 3 percent in Baluchistan. Sindh was slightly oversampled to ensure representation of the more urbanized districts of Hyderabad, Karachi, and Sukkur.

Selection of Facilities

In the second stage, facilities were selected from the public and private sectors. The sample of public facilities was drawn from the HMIS (Health Management Information System) master list of public health facilities provided by the Provincial Departments of Health. Comprehensive listings of private-sector facilities in Pakistan were available for 20 of the 24 sampled districts from a Population Council study conducted in 2008–10, providing information on bed size and other characteristics, allowing preparation of a list of the range of private-sector facilities in each of the three bed-size groups likely to provide postabortion care.2 Listing of private-sector facilities was conducted in the remaining four sampled districts to obtain information about relevant facilities needed for sample selection.3 Finally, a list was obtained of all public and private teaching hospitals in Pakistan recognized by the Pakistan Medical and Dental Council (PMDC).

All public- and private-sector teaching hospitals in the country (not only in the selected districts) that had gynecological and obstetrics wards with 50+ beds and had been registered before 2011 (for public hospitals) and 2008 (for private hospitals) were included in the HFS sample. For the public-sector nonteaching health facilities, we used a systematic random-sampling design, selecting 100 percent of DHQs, 79 percent of THQs, and 40 percent of RHCs in the selected 24 districts for inclusion in the HFS. A similar sampling design was used to select a representative sample of the three categories of private-sector facilities, but with smaller sample fractions (19 percent for large facilities, 6 percent for medium facilities, and 5 percent for small facilities), given the much larger number of private facilities in the universe. These proportions were sufficient to represent variation in each type of facility and for scaling up to provide representative estimates for all such facilities. In the final sample, 133 nonteaching public facilities and 81 nonteaching private facilities were selected (see Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of sample, by sector and type of facility, Pakistan, 2012

| Sector/type of facility | Number of national facilities capable of providing PAC | Total number of facilities in 24 sampled districts | Facilities in sampled districts, as a proportion within country | Number of facilities selected into sample | Sampling proportion within sample districts | Number of facilities interviewed | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 5,054 | 1,635 | 0.32 | 275 | 0.17 | 266 | 97.0 |

| Teaching hospitalsa | 61 | — | — | 61 | 1.00 | 54b | 89.0 |

| Public sector | |||||||

| DHQ | 97 | 24 | 0.25 | 24 | 1.00 | 24 | 100.0 |

| THQ | 165 | 58 | 0.35 | 46 | 0.79 | 44 | 96.0 |

| RHC | 570 | 158 | 0.28 | 63 | 0.40 | 63 | 100.0 |

| Private-sector facilitiesc | |||||||

| Large | 72 | 21 | 0.29 | 4 | 0.19 | 4 | 100.0 |

| Medium | 534 | 191 | 0.36 | 12 | 0.06 | 12 | 100.0 |

| Small | 3,555 | 1,183 | 0.33 | 65 | 0.05 | 65 | 100.0 |

PAC = Postabortion care. DHQ = District Headquarters Hospital. THQ = Tehsil Headquarters Hospital. RHC = Rural Health Center.

— = Not applicable.

All public and private teaching hospitals in Pakistan providing reproductive health care were included in the Health Facilities Survey sample.

Of the 61 selected facilities, 7 were not surveyed because of security reasons.

Facilities having the capacity to provide postabortion-care services were included in the universe from which the sample of private facilities was drawn.

SOURCE: Health Facilities Survey 2012.

To calculate national estimates, we derived weights based on sample selection and response rates. Response rates were very high in both the private and public sectors. Weights for teaching hospitals reflect only response rates (as 100 percent were included in the survey sample). For the public sector, the HMIS listings provided the bed size of all public facilities, and weights were calculated separately for each category of facility by province, integrating bed size into the weights. We divided the total number of beds for each facility type in each province (N) by the number of beds covered by the Health Facility Survey for that facility type in that province (n) to obtain the sample component of the weight (W = N/n); this was multiplied by the nonresponse component to provide the final weights.

To derive weights for private-sector health facilities, we used data from the GIS mapping survey for 20 of the sampled districts and from the special listing completed for the remaining four sampled districts, both of which provided data on the number of beds in all private-sector facilities by type of facility and province. We calculated the ratio of the number of beds in private-sector facilities likely to provide postabortion care4 to the number of beds in public facilities in these 24 districts. We then applied this ratio to the number of public-sector beds in nonsampled districts in the country (obtained from HMIS) to estimate the total number of beds in private-sector nonteaching facilities likely to provide postabortion care nationally. National weights are calculated on the basis of the total number of beds in private facilities likely to provide postabortion care and the number of beds in surveyed private facilities.

The questionnaire used for the HFS, adapted from the one used in an earlier study, was substantially modified to meet expanded objectives and to address additional issues. As far as possible, comparability was maintained in the wording of questions to permit the documentation of changes that occurred between 2002 and 2012.

Using a structured questionnaire, data were collected in each facility through face-to-face interviews with senior medical officials and health care providers5 working in the gynecology/obstetrics department. The primary aim of this inquiry was to assess Pakistan’s capacity to provide quality postabortion services and record the number of women being treated for postabortion complications as inpatients or outpatients, nationally, regionally, and by facility type. Questions were asked using two reference periods: the number of women treated at the facility in the past month and the number treated in an average month.

Health Professionals Survey

A total of 102 health professionals in a wide range of professions, including gynecology, were interviewed. The sample included respondents from the four major provinces, with a large proportion from Punjab and Sindh, which contain almost 80 percent of the national population. Thirty-six professionals were interviewed in Punjab, 37 in Sindh, 17 in KP, and 12 in Baluchistan. Respondents were selected on the basis of their knowledge and experience related to abortion and postabortion complications. Fewer than 10 percent had nonmedical backgrounds (senior health managers and researchers), and the remainder held positions in health care provision. Respondents with medical backgrounds (from public and private teaching hospitals as well as nonteaching hospitals) ranged from mid-level professionals (almost 20 percent were lady health workers, nurses, and midwives) to a more senior-level group comprising female medical officers (about 25 percent) and obstetrician/gynecologists (about 40 percent). We drew names of obstetricians and gynecologists for each province from the list of members of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Pakistan.

The aim of the HPS is to ascertain the perceptions of health professionals regarding the conditions under which women obtain induced abortions, including the types of methods employed, the providers and sources used, the probability of experiencing complications given the type of provider, and the probability of obtaining needed care for postabortion complications. Separate estimates were calculated for four population subgroups (rural poor, rural nonpoor, urban poor, and urban nonpoor). These data were used to calculate the proportion of all women having induced abortions who experience complications requiring care in a health facility, and the proportion who obtain such care within each province and nationally. These data are the basis for calculating a multiplier (the inverse of the proportion of women having an induced abortion who are likely to obtain treatment in a facility for postabortion complications) that is used for estimating the total number of induced abortions in a given year.

Other Sources of Data

Population estimates are based on the 1998 census, projected to 2012. The 2012–13 Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey was used as the source for age-specific fertility rates, the percent of women delivering in facilities, and the proportion of births that were unwanted and mistimed. The 2011–12 Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey was used to derive the percent distribution of women in the four subgroups (urban, rural, poor, non-poor). We also draw upon existing studies on abortion-related topics in Pakistan.

METHODOLOGY

We used the same methodology that was employed for the 2002 study of abortion incidence in Pakistan (Sathar, Singh, and Fikree 2007). This indirect estimation methodology was developed by the Guttmacher Institute in the early 1990s and has been applied in about 20 countries (Singh and Wulf 1994; Henshaw 1998; Singh et al. 2012; Juarez and Singh 2012). The advantage of our approach is that it produces estimates for the country as a whole and for each province of the total number of abortions, the annual abortion rate, and the abortion ratio. The study also provides data on the number and rate of women treated in health facilities for induced-abortion complications, an important indicator of abortion-related morbidity. The indirect method has three steps: (1) estimating the total number of postabortion-care cases treated in health facilities annually (based on HFS data); (2) estimating the number of post-abortion-care cases treated for spontaneous and induced abortion (a model-based estimate); and (3) calculating the multiplier factor (based on HPS data). The results from the last two steps are combined to estimate the total number of induced abortions.

Step 1: Estimating the Total Number of Postabortion Cases Treated in Health Facilities

Information collected by the HFS was weighted to represent all facilities in the country. The estimated weighted total number of women treated annually for postabortion complications in all public and private facilities, based on the 2012 HFS, is 712,000. This includes women who have been hospitalized because of complications from a spontaneous pregnancy loss, or miscarriage, rather than an induced abortion and must be separated out to obtain the numbers treated for induced abortions.

Step 2: Estimating the Number of Postabortion Cases Treated for Spontaneous and for Induced Abortion

An indirect method is used to estimate the number of women expected to be hospitalized for spontaneous miscarriages, based on the known biological pattern of pregnancy loss by gestation. The advantage of this method is that it is comparable across areas and populations. The distribution of miscarriages by length of gestation and the proportion of pregnancies ending as live births (not taking induced abortion into account) are both fairly constant across populations. Data on the distribution are available both historically and from clinic-based studies in the United States and other countries (Harlap, Shiono, and Ramcharan 1980; Bongaarts and Potter 1983).

We assume that late miscarriages (13–21 weeks’ gestation) are likely to be accompanied by complications that require care in health facilities. Late miscarriages may be expressed as a proportion of pregnancies ending in live births, and this standard proportion may then be applied to the actual number of live births in an area or country to obtain an estimate of the number of women having late miscarriages.

In the absence of induced abortion, miscarriages at 13–21 weeks’ gestation account for about 2.9 percent of all observed pregnancies (i.e., of pregnancies that are observed at five weeks’ gestation). This group of miscarriages may also be expressed as a proportion of live births (84.8 percent of all observed pregnancies end in live births), therefore late miscarriages are 3.4 percent of all live births (2.9/84.8 = 3.4 percent).6 The number of women likely to be hospitalized for a late spontaneous abortion was calculated in Table 2 by applying the proportion of 3.4 percent to the number of live births occurring in 2012 nationally in Pakistan (5.46 million).7

TABLE 2.

Number of live births, number of women treated in health facilities for abortion complications or late spontaneous abortion, and number of women treated for complications of induced abortion, among women aged 15–49, nationally and by province, Pakistan, 2012

| National/province | Number of women a | Number of births a | Number of women treated in health

facilities |

Number of women treated for complications

of induced abortionb

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All abortion-related complications | Complications related to late spontaneous abortion | Low | Medium | High | |||

| Pakistan | 44,745,059 | 5,464,548 | 712,380 | 89,816 | 505,792 | 622,564 | 739,335 |

| Punjab | 25,536,418 | 3,103,800 | 416,433 | 51,332 | 243,318 | 365,101 | 486,884 |

| Sindh | 10,595,223 | 1,276,804 | 174,908 | 25,514 | 89,130 | 149,394 | 209,658 |

| KP | 6,351,539 | 796,182 | 80,426 | 10,996 | 19,680 | 69,430 | 119,181 |

| Baluchistan | 2,261,879 | 287,762 | 40,613 | 3,876 | 10,591 | 36,737 | 62,883 |

KP = Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Based on estimates prepared by the Population Council. National totals exclude certain territories not covered by this study (see footnote 1).

See “Methodology” section for explanation of how the number of women treated for induced-abortion complications is estimated. Low and high estimates are lower and upper bounds of the confidence interval around the estimated number of women treated for abortion complications (medium), based on the 2012 Health Facilities Survey. Low and high values for provinces do not add up to national totals, because they are based on the confidence interval around each province’s mean value and around the national mean value, respectively; the medium values do not add up because of rounding.

SOURCE: Health Facilities Survey 2012.

Not all women who experience a late spontaneous abortion seek care or have access to health facilities. Because of limited access to health services, only a small proportion of women in Pakistan will visit an appropriate health facility. Lacking data from women on their experience of late spontaneous abortion and on whether they obtained medical care for these pregnancy losses, a proxy measure is used—the proportion of women giving birth who deliver in health facilities—as an estimate of the proportion of women having a late spontaneous abortion who receive care at a health facility (Singh et al. 2010). This last piece of information is available from the 2012–13 PDHS. Nationally, the survey shows, 48 percent of women delivered at a health facility, ranging from about 16 percent in Baluchistan to 41 percent in KP, 49 percent in Punjab, and 59 percent in Sindh.

The resulting estimated annual number of spontaneous abortion cases treated in facilities is 90,000, which is equivalent to 13 percent (89,816/712,380) of the total number of postabortion-care cases treated each year for abortion complications. When these women are subtracted from the total of 712,000 women treated for any postabortion complications, an estimated 623,000 women are treated for induced abortion complications in facilities each year.

Step 3: Calculating the Multiplier Factor and Total Number of Induced Abortions

It is generally accepted that the number of women treated for complications of induced abortion represent only a small proportion of those having an abortion, because many women who have clandestine abortions are not seen in health facilities and are thus not counted. Among all women having abortions, there are two other categories besides those who receive treatment in facilities. The first category consists of women who have a safe, though clandestine, induced abortion and who do not experience serious medical complications that require treatment in a health facility. Women who are likely to be able to obtain a safe abortion include those who are better-off financially and can afford the fees of trained health professionals, women who live in urban areas and have better access to modern medical care, and better-educated women who recognize the dangers of seeking an abortion from an unskilled provider and who can afford the cost of modern medical care. The second category includes women who have serious complications but do not obtain facility-based medical care (including women who die from abortions). This category includes women who may fear drawing attention to having done something illegal, may not know where to obtain treatment, may live too far from a medical facility, or may not be able to afford to travel to a facility or pay for treatment.

We need to estimate the proportion of women likely to be treated in health facilities for complications, among all women obtaining induced abortions. The inverse of this proportion is often referred to as a multiplier, or inflation factor, that is applied to the known number of women treated in facilities for induced abortion complications. For example, if 20 percent of women having abortions are treated for complications (i.e., one out of every five women), the inflation factor would be 5 and the number of postabortion-care cases would have to be multiplied by 5 to obtain an estimate of the total number of induced abortions that occur annually.

In general, the safer clandestine abortion services are, the higher the multiplier, because for every woman who obtained treatment in a facility, many are likely to undergo safe abortions that do not result in complications. Safety is not the only consideration. The multiplier is also a function of the general availability of emergency medical care in a given setting. Where such services are easily accessible, the proportion of women with complications who receive facility-based treatment will be higher.

The multiplier estimated for Pakistan is based on information obtained in the HPS from 102 health care professionals across the country on their perceptions of key aspects of abortion provision, differentiating according to four main population subgroups (poor urban, nonpoor urban, poor rural, and nonpoor rural); the percentage distribution of all women seeking an abortion according to the source (doctors, midwives, untrained providers, pharmacists, and the woman herself); the probability that a woman who obtained an abortion will experience serious medical complications attributable to each of these sources; and the probability that a woman will obtain medical care for such complications.

Combining this information, we calculate the proportion of all women seeking an abortion who are likely to have a serious medical complication and who are also able to obtain facility-based care (ranging narrowly from 24 percent among rural poor women, because of limited access to hospital care, to 28–30 percent among the other three groups). These proportions, weighted by the estimated population size of the four subgroups nationally, produce an overall proportion of 27.7 percent obtaining hospital care among all women who obtain an abortion. The national multiplier based on this proportion is 3.6 (100/27.7).

Estimates of the multiplier for the four major provinces were based on respondents in the HPS survey from the respective provinces, and on the composition of each province’s population according to socioeconomic status. The percentage of all women having abortions who experienced complications and were treated in a health facility range from a low of about 25 percent in Sindh to 27–31 percent in the other three provinces. Underlying these values are two counteracting factors—the use of unsafe methods (the proportion of women having a complication and needing care in a facility) and access to health care (the proportion of women obtaining care among those with complications needing care). The multiplier is 3.5 in Punjab, 4.0 in Sindh, 3.2 in KP, and 3.7 in Baluchistan.

The product of the number of women treated for induced-abortion complications and the multiplier yields an estimate of the total number of women having abortions nationally: 2,250,000 (623,000 × 3.6).

FINDINGS

We present estimates for 2012 of the incidence of treatment for postabortion complications, induced abortion, and unintended pregnancy. We comment on changes between 2002 and 2012 in all three measures, bearing in mind the limitations of the earlier study. The findings of the 2012 study are analyzed as far as possible on a provincial basis.

Treatment for Postabortion Complications

In 2012, an estimated 623,000 women in Pakistan were treated for complications resulting from induced abortion in public- and private-sectors facilities combined (95% CI: 506,000–739,000). This is an annual treatment rate of 13.9 per 1,000 women aged 15–49 (95% CI: 11.3–16.5). The treatment rate varies among provinces, with a rate of about 14 for Punjab and Sindh, compared with 11 in KP and 16 in Baluchistan. The rate of treatment reflects the combined effect of the level of safety of the abortion procedures and the care received at health facilities. The rate of treatment of abortion complications in Pakistan in 2012 is quite high in comparison with countries in the developing world where abortion is highly legally restricted, and where this rate typically ranges between 5 and 10 per 1,000 women (Singh 2006).

Approximately 62 percent of all women treated for an abortion complication in 2012 obtained care in a private facility, evidence of the large role of the private sector in providing postabortion care. The proportion treated in private-sector facilities is highest in Punjab (about 70 percent), high in Sindh (58 percent) and KP province (57 percent), and much lower in Baluchistan (22 percent).

An accurate assessment of the change in the overall treatment rate between 2002 and 2012 is not possible because the 2002 HFS did not survey a representative sample of private-sector facilities. However, we can compare complications treated in public facilities. Table 3 shows that the absolute number of complications treated in the public sector has increased only slightly between 2002 and 2012 despite the large population increase in the last decade. This is reflected in a decline in the complication treatment rate for the public sector, from 7.3 to 6.0 per 1,000. This rate has declined in three of the four provinces, most markedly in KP. However, it has increased in Baluchistan, where about 80 percent of postabortion care occurs in the public sector, from 9.6 to 14.0 per 1,000.

TABLE 3.

Number and rate of women treated for postabortion complications in the public and private sector, treatment rate for abortion complications, and percent of postabortion patients treated in the public sector, nationally and by province, Pakistan, 2002 and 2012

| National/province | Number treated for abortion complications

in public-sector facilities |

Treated complication rate (number treated

per 1,000 women aged 15–49, public sector) |

Number treated for abortion complications

in private-sector facilities |

Treated complication rate (number treated

per 1,000 women aged 15–49, private sector) |

Treatment rate for abortion complications per 1,000

women aged 15–49, combined public and private sector |

Percent of all post-abortion-care patients treated in

public-sector facilities |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 2012 | 2002 | 2012 | 2002 | 2012 | 2002 | 2012 | 2012 | 2012 | |

| Pakistan | 246,209 | 266,675 | 7.3 | 6.0 | na | 445,705 | na | 9.9 | 15.9 | 37.4 |

| Punjab | 126,267 | 126,789 | 6.7 | 5.0 | na | 289,644 | na | 11.3 | 16.3 | 30.4 |

| Sindh | 57,222 | 73,512 | 7.4 | 6.9 | na | 101,396 | na | 9.6 | 16.5 | 42.0 |

| KP | 47,580 | 34,715 | 10.7 | 5.5 | na | 45,711 | na | 7.2 | 12.7 | 43.2 |

| Baluchistan | 15,140 | 31,659 | 9.6 | 14.0 | na | 8,954 | na | 4.0 | 18.0 | 78.0 |

KP = Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. na = Not available.

SOURCE: Health Facilities Survey 2002 and 2012.

Lacking representative data on private-sector provision of postabortion care in 2002, we are unable to offer definitive answers to two important questions: (1) whether, and if so by how much, the overall rate of treated abortion complications increased during the past decade; (2) whether the role of the private sector in providing postabortion care increased, and if so by how much. Comparable data (not shown) on the private-sector proportion of facility-based deliveries show that a substantial increase from 12 percent to 34 percent occurred between 2001 and 2012 (Federal Bureau of Statistics 2003; PBS 2013), and by definition the role of the public sector declined. This trend provides support for expecting an increase in private-sector provision of postabortion-care services, and the relatively small decline in the public-sector rate of treatment for abortion complications also suggests that the overall rate of treatment for these complications increased over the past decade.

Incidence of Induced Abortion

Pakistani women had an estimated 2.25 million abortions in 2012 (95% CI = 1.84–2.68 million) (Table 4). Women in Punjab had an estimated 1.29 million induced abortions in 2012, and women in Baluchistan had about 136,000 abortions. The national abortion rate is 50 per 1,000 women aged 15–49 (95% CI = 41–60). Substantial variation exists among provinces, with the highest induced abortion rates in Baluchistan (60) and Sindh (57), followed by Pun-jab (51) and KP (35).

TABLE 4.

Range of estimates of total number of induced abortions, abortion rate, and abortion ratio, nationally and by province, Pakistan, 2012

| National/province | Total number of induced abortions a

|

Abortion rate (number of abortions per

1,000 women, aged 15–49) |

Abortion ratio (number of abortions per

100 live births) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | Low | Medium | High | |

| Pakistan | 1,835,520 | 2,250,087 | 2,683,047 | 41 | 50 | 60 | 34 | 41 | 49 |

| Punjab | 860,129 | 1,290,631 | 1,721,133 | 34 | 51 | 67 | 28 | 42 | 56 |

| Sindh | 357,502 | 599,220 | 840,938 | 34 | 57 | 79 | 28 | 47 | 66 |

| KP | 69,430 | 224,052 | 340,269 | 11 | 35 | 54 | 9 | 28 | 43 |

| Baluchistan | 39,262 | 136,184 | 233,106 | 17 | 60 | 103 | 14 | 47 | 81 |

KP = Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Medium estimate is point value estimated based on the Health Facilities Survey. Low and high estimates are based on confidence interval around the survey-based point estimate. See “Incidence of Induced Abortion” section for explanation.

SOURCE: Health Facilities Survey 2012.

The abortion ratio (the number of abortions per 100 live births) is a useful indicator of the likelihood that women who have experienced an unintended pregnancy would have an abortion rather than give birth. Nationally, the abortion ratio is 41 abortions per 100 live births, ranging from 47 in Sindh and Baluchistan to 28 in KP.

The only previous national study of abortion incidence estimated an abortion rate of 27 for women aged 15–49 in 2002 (Population Council 2004). However, as noted above, that study did not estimate postabortion services in the private sector, with the result that the estimate of abortion incidence may have underestimated the true rate even though the indirect estimation methodology is designed to estimate overall incidence through the multiplier. The abortion rate estimated for 2012 (50 per 1,000 women) implies an increase of 90 percent in the abortion rate for women aged 15–49 between 2002 and 2012 (Table 5). Even allowing for some underestimation in the rate for 2002, we conclude that a significant increase is likely to have taken place over this ten-year period.

TABLE 5.

Trends in abortion incidence, unintended pregnancy, and related indicators, women aged 15–49, Pakistan, 2002 and 2012

| Measure | 2002 a | 2012 b | Percent change (2002 to 2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of women | 33,618,228c | 44,745,059 | +33.1 |

| Number of live births | 4,614,258 | 5,465,548 | +18.4 |

| Number of abortions | 890,000 | 2,250,087 | +152.8 |

| Abortion rate (per 1,000 women) | 26.5c | 50.3 | +89.8 |

| Number of unintended pregnancies | 2,369,548 | 4,153,780 | +75.3 |

| Unintended pregnancy rate (per 1,000 women) | 70.5 | 92.8 | +31.6 |

| Percent of all pregnancies that are unintended | 37.6 | 46.0 | +22.3 |

| Total fertility rate (TFR)d,e | 4.8 | 3.8 | −20.8 |

| Wanted TFRd | 3.5 | 2.9 | −17.1 |

SOURCES:

For 2002 data: NIPS (2001); Sathar, Singh, and Fikree (2007).

For 2012 data: 2012 Health Facilities Survey and population projections by the Population Council.

Numbers for 2002 are not the same as published in Sathar, Singh, and Fikree (2007), because the earlier estimates were based on women aged 15–44 whereas the 2002 estimates presented here were recalculated and are based on women aged 15–49.

PRHFPS (NIPS 2001) and 2012–13 PDHS (NIPS and ICF International 2013).

Rates are based on events in the three years prior to the survey.

Unintended Pregnancy and Contraceptive Prevalence

The sum of all live births, abortions, and miscarriages (from intended and unintended pregnancies) equals the total number of pregnancies. To calculate unintended pregnancies nationally and by province, we summed the numbers of induced abortions, miscarriages attributable to unintended pregnancies, and unplanned births. The last measure was derived by multiplying the proportion of unplanned births (mistimed or unwanted at the time of conception) reported in the 2012–13 PDHS by the number of live births. To estimate the number of unintended pregnancies that end in miscarriage, we used a model-based approach from clinical studies of pregnancy loss by gestational age (Harlap, Shinto, and Ramcharan 1980; Bongaarts and Potter 1983). We applied the parameters from that model—pregnancy losses are estimated to be 20 percent of live births plus 10 percent of induced abortions—to the number of unplanned births and abortions respectively, to obtain the number of miscarriages resulting from unintended pregnancies. The number of planned pregnancies was calculated similarly, by summing planned births and miscarriages from intended pregnancies.

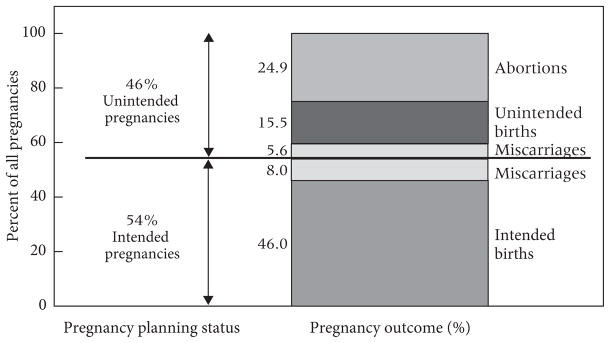

Out of a total of approximately 9 million pregnancies in Pakistan in 2012, 4.2 million (46 percent) are unintended (Table 6 and Figure 1). Of these 4.2 million unintended pregnancies, 54 percent end in induced abortions. An additional 34 percent of unintended pregnancies result in an estimated 1.4 million unplanned births. These abortions carry huge costs as witnessed by the large numbers of women who have postabortion complications and obtain treatment, as well as those who need but do not get treatment. Further, the unplanned births impose their own economic, social, and health costs on families, especially mothers.

TABLE 6.

Number of pregnancies, pregnancy rate, unintended pregnancy rate, percent of all pregnancies that are unintended, and percent distribution of unintended pregnancies by outcome, nationally and by province, Pakistan, 2012

| National/province | Number of pregnancies (births, abortions, and miscarriages) | Pregnancy rate per 1,000 women aged 15–49 a | Unintended pregnancy rate per 1,000 women aged 15–49b | Percent of all pregnancies that are unintended | Percent distribution of unintended

pregnancies by outcome |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unplanned births | Miscarriages | Induced abortions | |||||

| Pakistan | 9,032,553 | 202 | 93 | 46 | 34 | 12 | 54 |

| Punjab | 5,144,254 | 201 | 94 | 47 | 34 | 12 | 54 |

| Sindh | 2,191,307 | 207 | 92 | 44 | 27 | 12 | 62 |

| KP | 1,201,875 | 189 | 89 | 47 | 47 | 13 | 40 |

| Baluchistan | 495,117 | 219 | 95 | 44 | 25 | 11 | 63 |

Number of pregnancies (live births, abortions, and miscarriages) per 1,000 women aged 15–49 in 2012.

Number of unintended pregnancies (unplanned births, abortions, and miscarriages resulting from unintended pregnancies) per 1,000 women aged 15–49.

NOTE: All population data are based on Population Council projections for 2012.

FIGURE 1.

Pregnancy planning status and outcome of all pregnancies, Pakistan, 2012

Whereas little variation in the percentage of unintended pregnancies is seen across provinces, the proportion of unintended pregnancies resulting in induced abortions varies significantly. Sindh and Baluchistan have the highest proportions of unintended pregnancies ending in induced abortions (about 62 percent) (see Table 6). This proportion is lowest in KP, although still high at 40 percent.

It is interesting to note that (per the 2012–13 PDHS), while Punjab has the highest contraceptive prevalence rate (41 percent) and an abortion rate equal to the national average, Sindh and Baluchistan (with lower contraceptive prevalence rates of 30 percent and 20 percent, respectively) both have higher than average abortion rates. Women in these latter two provinces appear to use abortion as an important means of controlling unwanted fertility. In KP, where contraceptive use is only 28 percent, the abortion rate is also much lower than average, and the proportion of unplanned births is higher than average. More in-depth analysis is needed to identify the factors that are related to variations in unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, and abortion incidence among provinces. For example, both KP and Punjab report a higher use of traditional methods, which is usually coupled with higher use of abortion as a backup, but this does not appear to be the case.

As shown in Table 5, the unintended pregnancy rate increased between 2002 and 2012 from 71 to 93 per 1,000 women aged 15–49, and the percentage of unintended pregnancies increased from 38 to 46 percent. The underestimation of abortion in 2002 means that not all of the 32 percent increase in the unintended pregnancy rate is real, although given the substantial increase in abortion incidence that has likely occurred, it is likely that some of this increase is real. Several elements may be driving up unintended pregnancy and induced abortion. A relatively low overall contraceptive prevalence rate of 35 percent, a modern contraceptive prevalence rate of 26 percent, and a high first-year discontinuation rate of 37 percent (NIPS and ICF International 2013) all support the fact that contraceptive use in Pakistan is inadequate to meet the growing demand for fertility regulation.

DISCUSSION

The context of sexual and reproductive health in Pakistan is crucial for interpreting the findings of this study. While the latest DHS results for 2012–13 show slow improvements in key reproductive health indicators in Pakistan, there is a notable change in fertility and family-size preference. The decline over the past decade in average family size of one child per woman (from 4.8 to 3.8 children) and the decline in the wanted fertility rate from 3.5 to 2.9 children per woman are both significant trends. Notably, the gap of about one child between the wanted and actual fertility rate continues to be a critical challenge for policy and programs. These major changes in fertility and fertility preferences occurred in all provinces.

The findings from this study are consistent with these trends in fertility and fertility preferences. The fact that 4 million women report unintended pregnancies each year, half of whom have an abortion to avoid giving birth, reflects the very high level of unmet need for contraception and the high level of unwanted childbearing. Our findings also highlight some major issues regarding reproductive health service choices available in Pakistan. The contraceptive prevalence rate has increased by less than one percentage point per year over the past decade, rising from 28 percent in the 2001 Pakistan Reproductive Health and Family Planning Survey (PRHFPS) to 35 percent in the 2012–13 PDHS (NIPS 2001; NIPS and ICF International 2013). By comparison, the abortion rate appears to have increased by 90 percent over the same decade. Even allowing for an underestimation of the abortion rate in 2002, it is likely that the abortion rate increased at a substantially faster pace than did contraceptive prevalence, suggesting an increased reliance on induced abortion to avoid unwanted births. The increase in the abortion rate is likely to have contributed to the decline in fertility that occurred between 2001 and 2012–13.

The increased recourse to this reproductive strategy may be partly explained by wider access to improved abortion care services, such as misoprostol and manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) (Sathar et al. 2013). Compared with 2002, a much higher proportion of HPS respondents reported misoprostol and MVA as methods of abortion in 2012, and misoprostol was perceived by HPS respondents as one of the two most commonly used abortion methods, with dilation and curettage (D&C) being second (Sathar et al. 2013). The large increase in the absolute number of abortions and postabortion complications documented by this study may in part reflect increased use of misoprostol. While much of this use may be appropriate and correct, inadequate knowledge about dosages, poor quality of the drug itself, and a clinical failure rate of about 10 percent (Faúndes et al. 2007; Von Hertzen et al. 2007) are likely to account for a substantial number of incomplete abortions and an increased number of women treated in facilities. Misoprostol is mentioned by a large proportion of providers in the 2012 study, although it was totally lacking in the 2002 study. The MVA procedure is also mentioned more frequently in the 2012 study, though more so in urban areas (Sathar et al. 2013).

The decline in the proportion of women with postabortion complications treated as in-patients between 2002 and 2012 is also a strong indicator that women are presenting for less severe postabortion complications, likely a result of the decline in use of unsafe methods of self-induced abortion and an increase in use of misoprostol and MVA. Misoprostol and MVA have likely made a difference by increasing the safety of clandestine abortions in the past decade, especially in urban areas. Study findings show, however, that women still experience a high rate of complications. The number of women treated for abortion complications rose from 0.2 million in 2002 to 0.7 million in 2012. Even allowing for underreporting in 2002 because the private sector was not surveyed, it is likely that the number of patients experiencing abortion complications increased substantially over the past decade.

One possible factor driving this increase is a rise in the number of women resorting to abortion, which is plausible given the broad trends described above—a substantial decline in the number of children women have and the number they want, accompanied by a very slow increase in contraceptive use. Population growth and an increase in the number of women of reproductive age, while not contributing to a rise in the treatment rate, is an important factor explaining the increase in the absolute number of postabortion-complication patients between 2002 and 2012. As shown in Table 5, the number of women of reproductive age has increased by 33 percent as a result of population growth over the decade. Improved access to health care (including postabortion-care services), especially in urban areas, is likely another important factor underlying the increase in the treatment rate.

The poor state of public-health facilities in Pakistan, coupled with the rapidly increasing population exerting pressure on state institutions, has allowed the private sector to step in to provide health care to the majority of the population (Nishtar 2006; Afzal and Yusuf 2013). Women tend to prefer the higher quality of care offered at private facilities (Nishtar 2006). Reasons given for the increased use of private health care services include poorly equipped public facilities; nonavailability of contraceptives and certain medicines; low satisfaction with government facilities, especially among vulnerable groups; shortage of trained health workers (especially women); and staff absenteeism at public-sector facilities (World Bank 2010). A high priority among women seeking abortion-related care would be public-sector facilities that ensure confidentiality and better quality of care, such as that offered by private-sector providers. Most women who received postabortion care believed that private-sector providers behaved more respectfully, and even poor women with fewer resources preferred to pay the higher fees charged by private providers to ensure higher quality of care (Rashida et al. 2013).

The expansion in private-sector health care provision is likely to be an important factor underlying improved access to health care in general. The private sector has become the main source of outpatient consultations and maternal and child health services. A consistent rise in the prevalence of institutional deliveries between 2001 and 2012 has occurred, and the private sector’s share has risen consistently (FBS 2003; PBS 2013). This trend is consistent with the results of our study, which show that in 2012 the private sector played a large role in the provision of postabortion care. This is so despite the fact that public-sector facilities are mandated to provide postabortion care. But public-sector postabortion-care services appear to be limited and their quality is far from ideal. In addition, the total number of small private facilities capable of providing postabortion services is now about six times the number of equivalent public-sector facilities (Sathar et al. 2013).

There is also evidence that women, especially in rural areas, are more likely to consult a doctor for postabortion complications than they did in the past (Sathar et al. 2013). While women still consult traditional birth attendants (dais), there appears to be a trend toward seeking care from formally trained practitioners, even in rural areas and even among the poor who have limited choices of access and affordability. This is an encouraging trend given the tendency in Pakistan, as in many other countries, for women to avoid seeking care for post-abortion complications (Population Council 2004; Singh 2006; Rashida et al. 2013).

Although there have been some improvements in access to postabortion care, substantial gaps and barriers remain. About one-fourth of women who experience induced-abortion complications do not obtain needed care from health facilities, as estimated by key informants in the HPS (Sathar et al. 2013). Among those who do, the quality of care they receive often falls short. For example, the provision of contraceptive counseling and services as part of postabortion care remains inadequate. Providers report that about half of postabortion patients leave the facility with a family planning method; however, this proportion may be an overestimate because facility respondents might inflate their answers to appear in a more favorable light (Sathar et al. 2013). This is an important missed opportunity, because post-abortion-care patients are likely to be receptive to counseling about how to avoid another unintended pregnancy (Sathar et al. 2013). In addition, health facilities continue to rely on invasive procedures such as D&C rather than WHO-recommended procedures, such as misoprostol and MVA (WHO 2012a). The attitudes of providers toward women needing care for abortion complications also leaves much to be desired. Respondents interviewed in the HFS reported that two in five providers have negative attitudes toward clients receiving postabortion care, and about one-third believed that they are reluctant to treat postabortion-care patients (Sathar et al. 2013).

Implications for Policies and Programs

The incidence of induced abortion estimated by this study—2.25 million abortions annually and an abortion rate of 50 per 1,000 women aged 15–49—reflects an unexpectedly high use of abortion to limit unintended births. The estimated 712,000 postabortion-complication clients seeking treatment in health facilities also place an additional heavy burden on health systems, especially those in the public sector.

To reduce the number of women having unintended pregnancies and the number experiencing postabortion complications, the most urgent priority for policymakers and service providers is to improve access to quality contraceptive services, especially in rural areas. The finding of a high abortion rate in Pakistan demonstrates the need for quality contraceptive services in both the public and private sectors in each province. At present, the main government source of contraceptive services is the Department of Population and Welfare. The main public health system is not a source of supplies and does not offer family planning services. On the whole, the private sector also is not a major source of contraceptive provision. Public-sector provision of family planning and postabortion care is generally offered separately. The separation of these services discourages the provision of comprehensive care that would incorporate counseling for family planning when women seek help for postabortion complications and ideally even when women seek safe, clandestine abortion services.

To achieve an effective expansion of family planning services, the health sector has to mobilize its large network of services. This requires a realization within the health sector that family planning is an essential part of maternal, neonatal, and child health (MNCH) service provision and primary health care (Sathar, Wazir, and Sadiq 2013). At present, the provision of MNCH remains separated from family planning services. Furthermore, unlike the case of abortion care, the private sector is not “picking up” the responsibility for family planning. In general, NGOs are either unable or reluctant to provide services in rural and remote areas, leaving the field open mainly to drug dispensers, quacks, and poorly trained paramedics. This situation may change, however, if the virtual absence of public-sector contraceptive services is seen as an opportunity for a profitable market by private-sector providers, who will then have incentives to offer such services. A strong commitment from policymakers is needed, because expansion of public-sector services requires training of additional health care providers, integration of services requires new policies and guidelines, and ensuring the availability of quality contraceptive care requires an uninterrupted supply of a full range of contraceptive methods in primary health facilities.

Postabortion-care services in Pakistan are far from ideal in both the public and private sector. Public-sector facilities, in particular, lack essential equipment and personnel for providing WHO-recommended standards of postabortion services, such as MVA kits, disinfection equipment, and trained providers available around the clock (Sathar et al. 2013). Given that the provision of postabortion care is mandated in public-sector facilities, stronger policies and greater resources are needed to improve the training of doctors and mid-level providers in safer methods of managing postabortion complications. In addition, training in management of postabortion care should be part of training curriculums for all levels of health care providers. Efforts are underway in collaboration with the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Pakistan and other stakeholders to improve medical practice and adherence to recommended standards for providing such care, including steps for improving availability of essential equipment and medicines.

The findings presented in this article highlight the widespread need in Pakistan for better policies and programs to manage the health consequences of unsafe and clandestine abortion and to help women and couples prevent unintended pregnancies. We hope the findings stimulate policy discussions and lead to improvements in policies and service provision.

Footnotes

The study covers the four major provinces and excludes certain territories that were not covered in the sample of the HFS and HPS (i.e., AJK, FATA, and GB). The number of women aged 15–49 and the number of live births for 2012 are based on estimates prepared by the Population Council for the four major provinces.

“Mapping of Health and Reproductive Health Service Delivery Points.”

Four of the 24 sampled districts in Punjab province did not have comprehensive listings of private-sector facilities through prior GIS mapping, so a rapid count and listing of private-sector facilities was carried out for this study.

Private-sector facilities that had appropriately trained staff (including a female obstetrician/gynecologist) and necessary equipment available were considered capable of providing postabortion care.

Sex—male 6 percent, female 94 percent. Designation—gynecologists 29 percent, other doctors 49 percent, mid-level providers 22 percent.

Pregnancy losses at 22 or more weeks are not considered because they usually are not classified as abortions but as fetal deaths.

The annual number of births in Pakistan in 2012 is calculated by applying age-specific fertility rates for each five-year age group from the 2012–13 PDHS to the number of women of reproductive age (15–49) in each five-year age group.

References

- Afzal Uzma, Yusuf Anam. The state of health in Pakistan: An overview. The Lahore School of Economics. 2013;18:233–247. (Special Edition) [Google Scholar]

- Ahman Elisabeth, Shah Iqbal H. New estimates and trends regarding unsafe abortion mortality. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2011;115(2):121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badshah Sareer, Mason Linda, McKelvie Kenneth, Payne Roger, Lisboa Paulo JG. Risk factors for low birth-weight in the public-hospitals at Peshawar, NWFP-Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:197. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta Shereen, Aziz S, Korejo Razia. Surgical complications following unsafe abortions. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2003;53(7):286–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bongaarts John, Potter Robert. Fertility, Biology, and Behavior: An Analysis of the Proximate Determinants. New York: Academic Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley Sarah EK, Croft Trevor N, Fishel Joy D, Westoff Charles F. DHS Analytical Studies No. 25. Calverton, MD: ICF International; 2012. Revising unmet need for family planning. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell Bruce, Barkat-e-Khuda, Ahmed Shameem, Nessa Fazilatun, Haque Indrani. Pregnancy termination in a rural sub-district of Bangladesh: A micro study. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1999;25(1):34–37. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon BS, Chandhio N, Kambo I, Saxena NC. Induced abortion and concurrent adoption of contraception in the rural areas of India (an ICMR task force study) Indian Journal of Medical Sciences. 2004;58(11):478–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faúndes A, Fiala C, Tang OS, Velasco A. Misoprostol for the termination of pregnancy up to 12 completed weeks of pregnancy. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 2007;99(2):172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Statistics (FBS) [currently Pakistan Bureau of Statistics] Pakistan Integrated Household Survey (PIHS), Round 4: 2001–02. Islamabad, Pakistan: Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Fikree Fariyal, Rizvi Narjis, Jamil Sarah, Hussain Tayyaba. The emerging problem of induced abortions in squatter settlements of Karachi Pakistan. Demography India. 1996;25(1):119–30. [Google Scholar]

- Ganatra B, Hirve S. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharashtra, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 2002;10(19):76–85. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(02)00016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazdar Haris, Khan Ayesha, Qureshi Saman. Research report. Karachi, Pakistan: Collective for Social Science Research; 2012. Causes and implications of induced abortion in Pakistan, A social and economic analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Gilani Saima, Azeem Perveen. Induced abortion: A clandestine affair. Journal of Postgraduate Medical Institute. 2005;19(4):412–415. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Pakistan. The First Ordinance of the Qisas and Diyat Law. Islamabad, Pakistan: Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs (Law and Justice Division); 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harlap S, Shiono PH, Ramcharan S. A life table of spontaneous abortions and the effects of age, parity, and other variables. In: Porter IH, Hook EB, editors. Human Embryonic and Fetal Death. New York: Academic Press; 1980. pp. 145–158. [Google Scholar]

- Henshaw Stanley. Abortion incidence and services in the United States, 1995–1996. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(6):263–270. 287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzen Helena von, Piaggio Gilda, Huong Nguyen Thi My, et al. Efficacy of two intervals and two routes of administration of misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy: A randomised controlled equivalence trial. The Lancet. 2007;369(9577):1938–1946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamal Haroon. Research Report No. 70. Karachi, Pakistan: Social Policy and Development Centre; 2007. Income poverty at district level: An application of small area estimation technique. [Google Scholar]

- Juarez Fatima, Singh Susheela. Incidence of induced abortion by age and state, Mexico 2009: New estimates using a simplified methodology. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;39(2):58–67. doi: 10.1363/3805812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamran Iram, Arif Shafique, Vassos Katherine. Concordance and discordance of couples in a rural Pakistani village: Perspectives on contraception and abortion—a qualitative study. Global Public Health. 2011;6(1):38–51. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.590814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan Ayesha. Unsafe abortion-related morbidity and mortality in Pakistan: Findings from a literature review. Karachi, Pakistan: Collective for Social Science Research; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khan Ayesha. Induced abortion in Pakistan: Community-based research. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2013;63(4):27–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhu Das Chandra, Srichand Pushpa. Maternal mortality and morbidity due to induced abortion in Hyderabad. Journal of Liaquat University of Medical and Health Sciences. 2006;5(2):62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud G, Mushtaq Z. The incidence and outcome of induced abortions at one of the hospitals of Islamabad. Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Association of Pakistan; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] Pakistan Reproductive Health and Family Planning Survey (PRHFPS) 2000–01. Islamabad, Pakistan: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and ICF International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13. Islamabad, Pakistan, and Calverton, MD: NIPS and ICF International; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Population Studies (NIPS) [Pakistan] and Macro International. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey (PDHS) 2006–07. Islamabad, Pakistan: NIPS and Macro International; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Nishtar Sania. The gateway paper: Health system in Pakistan—a way forward. Islamabad, Pakistan: Pakistan’s Health Policy Forum and Heartfile; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pakistan Bureau of Statistics (PBS) Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement (PSLM) Survey (2011–12) Islamabad, Pakistan: Government of Pakistan, Statistics Division, Pakistan Bureau of Statistics; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Population Council. Report on unwanted pregnancy and post abortion complications in Pakistan: Findings from a national survey. Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Anika, Katzive Laura, Henshaw Stanley K. A global review of laws on induced abortion, 1985–1997. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;24(2):56–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Anjum, Fatima Saher, Gangat Shoaib, Ahmed Afzal, Memon Iqbal Ahmed, Soomro Nargis. Bowel injuries secondary to induced abortion: A dilemma. Pakistan Journal of Surgery. 2007;23(2):122–125. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman Mizanur, DaVanzo Julie, Razzaque Abdur. The role of pregnancy outcomes in the maternal mortality rates of two areas in Matlab, Bangladesh. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;36(4):170–177. doi: 10.1363/3617010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashida Gul, Sathar Zeba, Singh Susheela, Shah Zakir, Kamran Iram, Eshai Kanwal. Post abortion care in Pakistan: The influence of gender and poverty. Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rashida Gul, Shah Zakir, Fikree Fariyal, Faizunnisa Azeema, Mueenuddin Lauren. Abortion and post-abortion complications in Pakistan: Report from health care professionals and health facilities. Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem Sarah, Fikree Fariyal. Induced abortions in low socio-economic settlements of Karachi, Pakistan: Rates and women’s perspectives. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2001;51(8):275–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleem Sarah, Fikree Fariyal. The quest for small family size among Pakistani women: Is voluntary termination of pregnancy a matter of choice or necessity? Journal of Pakistan Medical Association. 2005;55(7):288–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathar Zeba, Singh Susheela, Fikree Fariyal F. Estimating the incidence of abortion in Pakistan. Studies in Family Planning. 2007;38(1):11–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathar Zeba, Singh Susheela, Shah Zakir, Rashida Gul, Kamran Iram, Eshai Kanwal. Post-abortion care in Pakistan: A national study. Islamabad, Pakistan: Population Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sathar Zeba, Wazir Asif, Sadiq Maqsood. Struggling against the odds of poverty, access, and gender: Secondary schooling for girls in Pakistan. The Lahore Journal of Economics. 2013;18:67–92. Special Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Zunaira Shaikh, Abbassi Razia Mustafa, Rizwan Naushaba, Abbasi Sumera. Morbidity and mortality due to unsafe abortion in Pakistan. International Journal of Gynaecology & Obstetrics. 2010;110(1):47–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique S, Hafeez M. Demographic and clinical profile of patients with complicated unsafe abortion. Journal of College of Physicians and Surgeons of Pakistan. 2007;17(4):203–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela. Hospital admissions resulting from unsafe abortion: Estimates from 13 developing countries. The Lancet. 2006;368(9550):1887–1892. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69778-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela, Hossain Altaf, Maddow-Zimet Isaac, Bhuiyan Hadayeat Ullah, Vlassoff Michael, Hussain Rubina. The incidence of menstrual regulation procedures and abortion in Bangladesh, 2010. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2012;38(3):122–132. doi: 10.1363/3812212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela, Remez Lisa, Tartaglione Alyssa. Methodologies for estimating abortion incidence and abortion-related morbidity: A review. New York: Guttmacher Institute; Paris: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Singh Susheela, Wulf Deirdre. Estimated levels of induced abortion in six Latin American countries. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1994;20(1):4–13. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Division (UNPD) Abortion policies: A global review. New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Vlassoff Michael, Singh Susheela, Suarez Gustavo. Abortion in Pakistan. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2009. In Brief No. 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Hertzen Helena, Piaggio Gilda, Arustamyan Karine, et al. Efficacy of two intervals and two routes of administration of misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy: A randomised controlled equivalence trial. The Lancet. 2007;369(9577):1938–1946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60914-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. Report No. 68258. Washington, DC: 2010. [Accessed 17 October 2014]. Delivering better health services to Pakistan’s poor. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/12369. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems. Geneva: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008. 6th edition. Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Safe abortion: Technical and policy guidance for health systems. 2nd edition. Geneva: 2012a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) Unsafe abortion incidence and mortality: Global and regional levels in 2008 and trends during 1990–2008. Geneva: 2012b. [Google Scholar]