Abstract

Latino drinkers experience a disparate number of negative health and social consequences. Emergency Department Alcohol Screening Brief Intervention and Referral to Treatment (ED-SBIRT) is viable and effective at reducing harmful and hazardous drinking. However, barriers (e.g. readily available language translators, provider time burden, resources) to broad implementation remain and account for a major lag in adherence to national guidelines. We describe our approach to the design of a patient-centered bilingual Web-based mobile health ED-SBIRT App that could be integrated into a clinically complex ED environment and used regularly to provide ED-SBIRT for Spanish speaking patients.

Keywords: Alcohol, Latino, Emergency Department, screening, mHealth

INTRODUCTION

Traditionally, emergency department-based alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment (ED-SBIRT) has been conducted in the context of physicians, nurses, social workers or paraprofessional advocates engaging patients one-on-one in intervention-focused interviews about drinking and related medical conditions. However, several unique and important clinical-setting barriers remain to broad implementation of ED-SBIRT i.e. excessive maintenance costs, training, time constraints, physician access, lack of intervention fidelity, and inability to easily reach a rapidly growing Spanish speaking population. As a result, routine ED-SBIRT practice across the nation lags behind national guidelines.(Cunningham et al., 2010) Health information technology is a compelling method to deliver low-cost, time saving, high fidelity, multi-lingual ED-SBIRT(F. Vaca, Winn, Anderson, Kim, & Arcila, 2010; F. E. Vaca, Winn, Anderson, Kim, & Arcila, 2011). As mobile health (mHealth) continues to grow as a delivery medium for patient-centered health information, the design and development methods of mHealth solutions becomes increasingly important. Our best practice approach to ED-SBIRT demonstrates how health information technology positively affects the delivery of essential and effective public health interventions. In this article, we provide an overview on some of the methods and techniques for the design and development of an interventional bilingual (English and Spanish) audiographical mHealth ED-SBIRT application.

Our ED-SBIRT Automated Bilingual Computerized Alcohol Screening and Intervention (AB-CASI) mobile App has the potential to not only expand the reach of alcohol screening, treatment initiation, and treatment referral to vulnerable ED populations but to also overcome fidelity, time, and cost barriers. Specifically, we focus on describing the development experience of patient-centered mobile health application such as AB-CASI and highlight challenges and lessons learned. Moreover, we show how we used mHealth to create capacity for low-cost, timesaving, high fidelity, multi-lingual ED-SBIRT.

BACKGROUND

The burden of disease and toll on human life due to alcohol is staggering. As the most commonly used drug in the U.S., consequences of misuse persist as major short-term and life-long threats to individual and community health. Alcohol-related deaths are the 3rd leading cause of preventable death for Americans. Nearly 80,000 alcohol-attributable deaths per year accounted for 2.3 million years of potential life lost from 2000-2005. The cost of alcohol misuse exceeds that of asthma, diabetes and high blood pressure combined. Risky drinkers account for 60% of alcohol-related absenteeism, tardiness, and poor work quality. Alcohol screening and brief intervention in the medical setting is critical. Over 19 million Latinos accessed healthcare through U.S. EDs in 2009. With the millions of annual alcohol-related injuries and medical co-morbidity visits to U.S. EDs, these encounters provide an opportunity to identify, intervene, and initiate treatment in the lives of those with AUDs. Herein lays an important opportunity for testing the identification, early intervention, and treatment initiation strategies in this vulnerable population group. Broad and consistent integration of alcohol screening and brief intervention in the medical setting is greatly needed.

In the last decade, the U.S. Latino population grew by 43% compared to 5% of the non-Latino population to comprise more than 50 million (33.3 million are 18 years and older).(Control & Prevention, 2004; Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011) This increase exceeded half of the U.S. population growth. The average age of the U.S. Latino population is 10 years younger than the overall U.S. population. This population characteristic touches only the very surface of this groups’ vulnerability. The size of the U.S. Latino population is expected to triple by 2050 comprising one-third of the U.S. population. With ongoing national efforts to eliminate health disparities, the rapid population growth of U.S. Latinos has major implications for the extent to which alcohol-related disparities can be reduced. This is of particular concern given the context of the U.S. Latino population growth outpacing any evidence of reduction of existing disparity.

For U.S. Latinos, consequences of drinking and disparities in specialized treatment are profound with a predictable likelihood to worsen as the population growth accelerates. Studies document the greater burden of disease from both social and health perspectives in Latino drinkers as compared to those of other race and ethnicities.(Caetano, Clark, & Tam, 1998; Mulia, Ye, Greenfield, & Zemore, 2009) Latino men have the highest prevalence of daily heavy drinking with prolonged duration and are more likely to binge drink. (Chen, 2006) Moreover, although non-Latino Whites are more likely than Latinos to succumb to alcohol dependency in their lifetime, once alcohol dependence occurs, Latinos have a higher prevalence than non-Latino Whites of recurrent or persistent alcohol dependence. Latinos also have higher rates of alcohol-related consequences, such as driving while intoxicated and lifetime arrests for driving under the influence of alcohol. (Caetano & Clark, 2000) Finally, a paucity of research has focused on the important distinction between ethnic variations as it relates to Latino subgroups (i.e. of Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican descent) and alcohol use disorders (AUD).

While a recent national study shows no significant relationship between acculturation and alcohol-related social problems, birthplace for both Latino men and women is noted as an independent risk factor. Nearly 50% of U.S. Latinos are foreign born, and for some Latino subgroups there exists an even greater level of vulnerability within an already “at-risk” population in the context of AUDs. Herein lays an important opportunity for testing the identification, early intervention, and treatment initiation strategies in this vulnerable population group.

Tablet touch screen with text-to-speech interfaces addresses literacy issues and makes automated ED-SBIRT an option for inexperienced computer users. Language translation (text and audio) of the automated ED-SBIRT is the single most important cultural adaptation that can be undertaken. Without it, non-English speaking language groups, often with the greatest need of screening and intervention, are overlooked. Field et al. were successful in demonstrating that ED-SBIRT was efficacious in Latino Spanish speaking patients with only linguistic translation.(Field, Caetano, Harris, Frankowski, & Roudsari, 2010) However, this study required extensively trained bilingual providers (bilingual master’s level or degreed clinicians) who performed the brief motivational intervention. The practicality of implementing this intervention in EDs across the country is seriously limited given the scarcity of bilingual clinicians in addition to other listed barriers. The use of an automated bilingual ED-SBIRT has already demonstrated feasibility, bilingual ED patient acceptability, and indications of efficacy.(D’Onofrio, Bernstein, & Rollnick, 1996; Field et al., 2010; Lotfipour et al., 2013; F. E. Vaca et al., 2011)

It is practical and can lead to ED cost savings in several ED-SBIRT areas (personnel, interpreter services, patient recidivism).

The potential of mHealth to meet the needs of ED-SBIRT was based on the growing body of evidence supporting the use of web-based solutions and multimedia presentations in SBRIT.(Bewick et al., 2010; Donoghue, Patton, Phillips, Deluca, & Drummond, 2014; Spijkerman et al., 2010) In a study investigating alternatives to the traditional SBRIT process, Neumann et al. explored the use of a computerized tool to improve the ED-SBIRT intervention.(Jimison, Sher, Appleyard, & LeVernois, 1998) Findings showed that patients felt the traditional approach could be replaced with the computerized intervention. Moreover, mHealth tools can also empower patients by assisting them in making critical decisions regarding their health and disease prevention.(Legare, Ratte, Gravel, & Graham, 2008; O’Connor et al., 2009; Pellisé & Sell, 2009; van Til et al., 2009) mHealth can be used to automate ED-SBIRT to significant reduce time and resource challenges while providing patient anonymity that lends itself well to self-disclosure of sensitive topics. With mHealth, there is the opportunity to optimize intervention fidelity and integrity, which is important given the variations and differences that exist in accuracy and reliability of measures across different race and ethnic groups.

AB-CASI is unique in its ability to address alcohol use disorders with bilingual capability in a very busy clinical setting where a teachable moment exists. Alcohol related injury and disease is a major cause of morbidity and mortality and contributes to health disparities in the U.S. in several areas. AB-CASI captures the full spectrum of patients that are harmful and hazardous drinkers through alcohol dependence and integrates motivational interviewing techniques to encourage and facilitate health behavior change for health promotion and disease prevention.

In this paper we provide a description of our experience in automating ED-SBIRT to reduce time and resource challenges while providing patient anonymity. Additionally, We show the best practice approach to design and developed mHealth App to conduct ED-SBIRT. We describe the health information technology (HIT) methods and techniques we used in the development of AB-CASI and our approach to resolve design challenges.

METHODS

The potential of mHealth to meet the needs of ED-SBIRT was based on the growing body of evidence supporting the use of web-based solutions and multimedia presentations in SBRIT. Moreover, mHealth tools like AB-CASI can also empower patients by assisting them in making critical decisions regarding their health and disease prevention. The main goals of the development of AB-CASI were:

-

Use mHealth to overcome important and persistent barriers encountered in ED-SBIRT implementation, including:

Practitioner time burden

Limited knowledge of brief intervention strategies (that can compromise fidelity)

Limited resources in screening and intervention personnel

Inability to easily provide ED-SBIRT in multiple languages

-

Use mHealth to facilitate and promote the following tasks:

Perform bilingual and automated Emergency Department alcohol screen

Conduct brief negotiation and intervention (BNI)

Provide appropriate referral to specialized treatment information

In this section, first, we describe how we used user-centered design approach (UCD) to help us focus on the users needs, wants and limitations to achieve user satisfaction. Then we discuss our approach for designing the architecture and the tools we used. We also describe the two main types of AB-CASI users interfaces. Finally, we briefly describe the tests we conducted through out the development.

User-Centered Design Approach

The user-centered design (UCD) approach was used in the design and development of AB-CASI mobile App. We used the iterative multi-stage design approach that involved the user’s input throughout the development process.(Demiris et al., 2008; Lyng & Pedersen, 2011) (Abras, Maloney-Krichmar, & Preece, 2004) UCD allowed us to conduct multiple user experience evaluations throughout the rapid prototyping and iterative development process. The final system was developed and optimized with an intentional focus on how patients can, want, and/or need to use the mHealth tool.

The concept for the AB-CASI mobile App emanated from challenges noted in the clinical setting and documented in the literature, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) guide lines, patient input, and subject matter expert interviews. This information was used to create initial computational model. The goal statement and task analysis formed the basis for the App’s functional and technical requirements, which are a list of required characteristics. Functional prototypes were created based on the App requirements as well as from findings from the user experience evaluations.

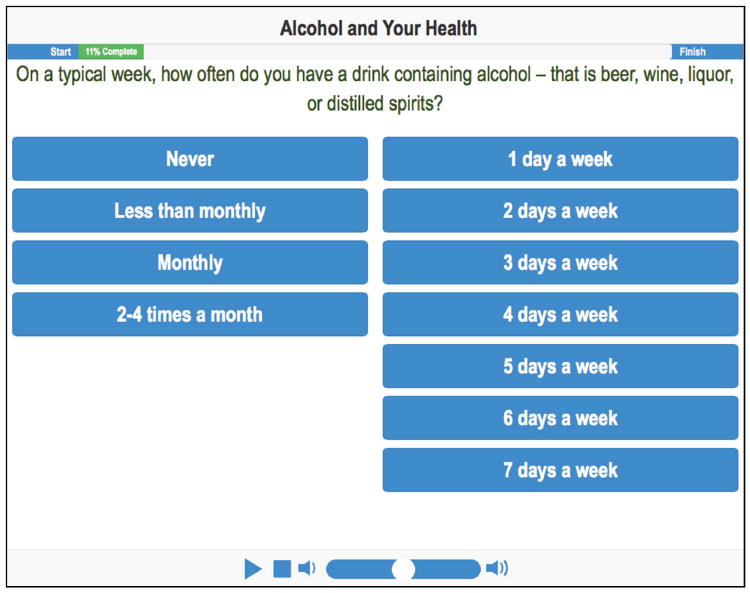

Once the functional and technical requirements were specified, we began the App design. Flowcharts of the main processes of the App were developed. For each screen, a mockup screen was created that included the content and layout of the page and the description of the navigation controls to be used (Figure 1. and Figure 2.).

Figure 1.

AB-CASI Language Selection Screen

Figure 2.

AB-CASI Frequency of Drinks Screen

The UCD approach facilitates the ability to obtain extensive attention to the user’s input at each stage of the design process and allows User Experience (UX) evaluations to be incorporated into the design.(Hassenzahl, 2008) We conducted a series of UX evaluations that mapped on to the development cycle for AB-CASI development

Solutions, Architecture, and Tools

Because the implementation of AB-CASI was to be in a busy emergency department, parameters in this project design were defined based on the environmental context. Potential solutions were identified and their strengths and weaknesses evaluated. For example, we considered and analyzed the benefits and the limitation of a Web-based mobile App vs. iPad® native App. A web-based App approach was selected and developed for the following reasons:

Using HTML5 and CSS3, allows for the development of a highly interactive App that works well on the iPad®

The Safari web browser provides touchscreen compatibility equivalent to the native Apps

There is a plethora of development resources and tools available for the web development

The web-based development approach can speedup the development process and allow for websites faster updates

Both short-term and long-term goals of AB-CASI App were considered in the design and architecture of these environments.

AB-CASI Users Interfaces

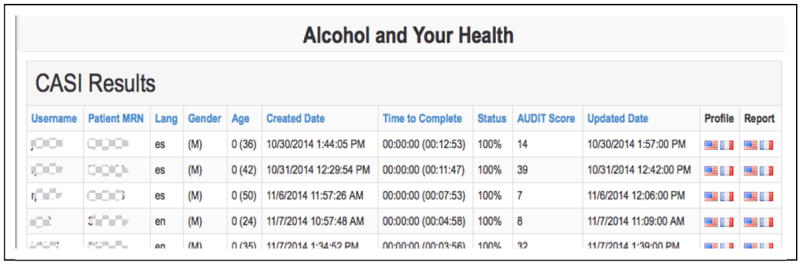

The development of AB-CASI encompassed the designed of two separate interfaces. One interface was for patients use on the iPad® and the other was PC interface for the tool management and administration tasks (Figure 3). Patients needed to be able to interact with a highly interactive websites that worked well on an iPad®.

Figure 3.

AB-CASI Tool Management and Administration Interface

Furthermore, because the application would be used in a dynamic clinical setting, we anticipated that patients could be occasionally interrupted during a work session.

As a result, we integrated the ability to save patient work sessions and have the ability to return to, resume, and complete the same screening and intervention work session. Also, AB-CASI administrators needed to have quick and near-real-time access to review the progress of an active work session, detailed information for each patient, and the result of the screening process. Finally, administrators would need to print specific patient tailored instructions upon completion of a work session.

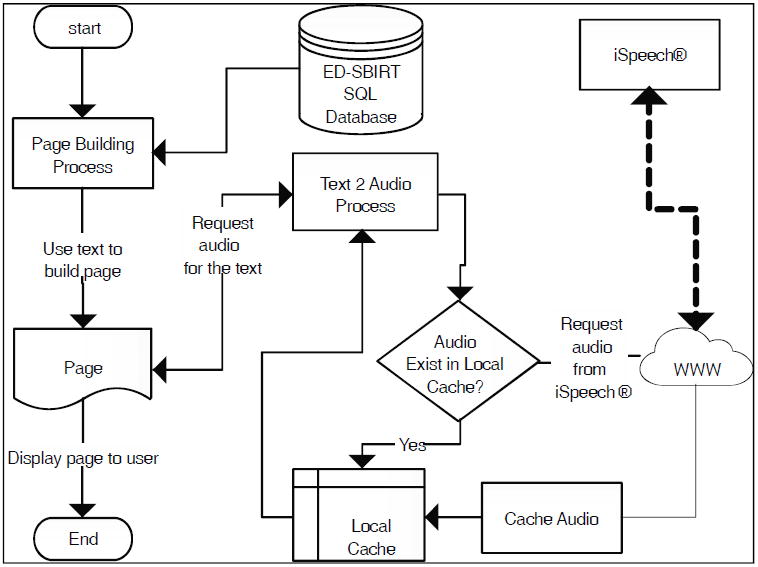

One design challenge that we faced was text-to-speech translation. A key feature of the AB-CASI mobile App is the bilingual (English and Spanish) audiographical capability that combines an online and automated text-to-speech translation. Our challenge was to find low cost solution to translate text, in English and Spanish, into speech in high quality audio with minimal cost and without compromising App performance (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Architecture of ED-SBIRT Mobile App Bilingual Text-to-Speech Generation

One way to add the audiographical functionality to a mobile App is to record the audio associated with textual content of every screen in waveform. Next, store the wave file in the database and link it with the equivalent text on the screen. Finally, have the App playback the audio recording associated with specific text when the screen is displayed. Although, this method can yield the most natural speech, it needs considerable resources in terms of human resources, audio recording capabilities, and data storage. In addition, it requires new audio every time the text changes.

A more efficient way, is to use Text-To-Speech (TTS), a method for converting text to synthetic speech using a computers.(Moulines & Charpentier, 1990) We selected an online TTS solution (www.ispeech.org) to handle text to speech translation. First, we identify the text that will be displayed on the various pages of the App and store this text in database tables. Later, this text is used to build the page before displaying it to the user. While building the page, the application requests audio files associated with text from the Audio-Process. If this is the first time the text is being used, the Audio-Process will request the equivalent audio translation from the web service provided by iSpeech Application Program Interface (API). The API will then take in the text string as an input and return of an MP3 file. The file is then stored in the local cash and linked to the corresponding text entry. If the application is to display the same text is on the screen again then the Audio- Process will recall the MP3 file that was stored in the local cash.

User Testing

We conducted user testing at the early stages of development.(Baylis, Kushniruk, & Borycki, 2012; Yen & Bakken, 2012) Users can provide early and valuable feedback. Users were group into subjects matter experts, experienced users, and patients. Subject matter experts participated in the early stages of testing of the initial prototype. Their reviews and comments were incorporated in the system revisions. We included the more experienced users in the testing process. These participants were part of our research team who were not involved in the early stages of the design. They provided comments and suggestion both on the interface and the subject content. Once the feedback from the experienced users group was incorporated in the App, another phase of testing and revision was started. The testing phase was continued with patients to gain user input on the system usability and greater clarity in understanding if the app was meeting its intended purpose. Users indicated that the App was easy to follow and to use. Feedback from this testing phase was evaluated and incorporated into ongoing development. Thereafter, our expert user group tested the final product to confirm that all desired changes had been implemented.

RESULTS

Following sequential testing of the prototype App, we found the Web-based App architecture to be the most appropriate fit for the busy ED clinical context. The software architecture for automated text-to-speech translation was quick and efficient with highly biofidelic in enunciation and pronunciation.

As mobile health (mHealth) continues to grow as delivery medium for patient-centered health information, the best practice design and development methods of mHealth solutions becomes increasingly important.

The User-Centered Design approach facilitated obtaining the user’s input at each stage of the design process.

The web based App architecture with the use of HTML5 and CSS3, allowed for the quick development of AB-CASI that works well on the iPad® using Safari web browser.

Providing two separate interfaces for AB-CASI (iPad® and PC) allowed us to build a highly interactive website that worked well for patients as well as administrators.

Incorporating user testing in the iterative development process provided early and valuable feedback.

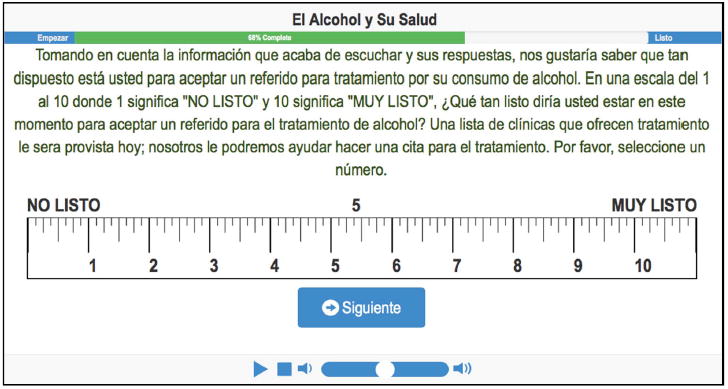

The Bilingual nature allowed for communication in this vulnerable population and without it clinical outcomes would never improve particularly given the cost and lack of availability of translations services. AB-CASI addressed both of these issues and as a result has the capacity to improve patient outcomes (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

AB-CASI Ruler Screen

DISCUSSION

The use of health information technology can be successful in screening, intervention, and referral. More specifically, in facilitating the delivery of ED-SBIRT and the communications involving health care providers and vulnerable populations that may have alcohol use disorders. The evidence that a computerized and web-based motivational intervention for alcohol abuse prevention can be efficacious is compelling. Using HTML5 and CSS3, one can create highly interactive websites that work well on iPad®. The use of mHealth tablet-based Ed-SBIRT tool provides patient anonymity that lends itself well to self-disclosure of sensitive or taboo subjects. The design and development of mobile ED-SBIRT tools needs to be agile and focuses on rapid prototyping.

Our experience in the development of the AB-CASI program shows that users are willing to make an initial investment of time to tryout new and innovative intervention if they feel that the intervention provide customized and private interaction. A deep understanding of the impact of a new system on the diverse group of end users persuaded the system design team to be flexible in its approach. The user-centered design approach facilitates interfacing with multiple players, bringing disparate entities together. Tablet-based touch screen with text-audio interfaces addresses literacy issues and makes automated ED-SBIRT an option for inexperienced computer users. Language translation (text and audio) of the automated ED-SBIRT is the single most important cultural adaptation that can be initially undertaken. AB-CASI reaches highly vulnerable populations because of its bilingual capability – nearly all-previous ED-SBIRT studies have excluded the enrollment of Spanish speaking populations. The resulting AB-CASI mobile App has the potential to benefit millions of vulnerable ED patients with alcohol use disorder and surmount several notable and persistent barriers to broad implementation of ED-SBIRT.

CONCLUSION

Our Web-based mobile ED-SBIRT App with bilingual text-to-speech audio translation and iPad® interface offers a compelling means to surmount existing implementation barriers. Our App architecture intentionally and readily addresses translation needs for alcohol ED-SBIRT in Spanish speaking ED patients. This has important implications for facilitating more meaningful and broader implementation of ED-SBIRT, enhancing patient communication, and reducing Spanish translator need burden. AB-CASI delivers low-cost, timesaving, high fidelity, multi-lingual ED-SBIRT.

Acknowledgments

Research supported by the National Institute On Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health, Office Of The Director, National Institutes Of Health (OD), Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (OBSSR) under Award Number R01AA022083

References

- Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D, Preece J. Bainbridge, W. Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction. 4. Vol. 37. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2004. User-centered design; pp. 445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Baylis TB, Kushniruk AW, Borycki EM. Low-cost rapid usability testing for health information systems: Is it worth the effort? 2012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewick BM, West R, Gill J, O’May F, Mulhern B, Barkham M, Hill AJ. Providing web-based feedback and social norms information to reduce student alcohol intake: a multisite investigation. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(3):e59. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL. Hispanics, Blacks and Whites driving under the influence of alcohol: Results from the 1995 National Alcohol Survey. Accident Analysis & Prevention. 2000;32(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0001-4575(99)00049-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caetano R, Clark CL, Tam T. Alcohol consumption among racial/ethnic minorities. Alcohol health and research world. 1998;22(4):233–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM. Alcohol use and alcohol use disorders in the United States: Main findings from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC) National Institute on Alcohol and Alcoholism; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Control, C. f. D., & Prevention. Alcohol-attributable deaths and years of potential life lost--United States, 2001. MMWR: Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2004;53(37):866–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham RM, Harrison SR, McKay MP, Mello MJ, Sochor M, Shandro JR, D’Onofrio G, et al. National survey of emergency department alcohol screening and intervention practices. Annals of emergency medicine. 2010;55(6):556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Onofrio G, Bernstein E, Rollnick S. Case studies in emergency medicine and the health of the public. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett; 1996. Motivating patients for change: a brief strategy for negotiation. [Google Scholar]

- Demiris G, Afrin LB, Speedie S, Courtney KL, Sondhi M, Vimarlund V, Lynch C, et al. Patient-centered Applications: Use of Information Technology to Promote Disease Management and Wellness. A White Paper by the AMIA Knowledge in Motion Working Group. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2008;15(1):8–13. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donoghue K, Patton R, Phillips T, Deluca P, Drummond C. The effectiveness of electronic screening and brief intervention for reducing levels of alcohol consumption: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(6):e142. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R, Harris TR, Frankowski R, Roudsari B. Ethnic differences in drinking outcomes following a brief alcohol intervention in the trauma care setting. Addiction. 2010;105(1):62–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassenzahl M. User experience (UX): towards an experiential perspective on product quality; Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 20th International Conference of the Association Francophone d’Interaction Homme-Machine.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Humes K, Jones NA, Ramirez RR. Overview of race and Hispanic origin, 2010. US Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration, US Census Bureau; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jimison HB, Sher PP, Appleyard R, LeVernois Y. The use of multimedia in the informed consent process. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1998;5(3):245–256. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1998.0050245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Legare F, Ratte S, Gravel K, Graham ID. Barriers and facilitators to implementing shared decision-making in clinical practice: update of a systematic review of health professionals’ perceptions. Patient Education and Counseling. 2008;73(3):526. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lotfipour S, Cisneros V, Anderson CL, Roumani S, Hoonpongsimanont W, Weiss J, Vaca F, et al. Assessment of alcohol use patterns among Spanish-speaking patients. Substance Abuse. 2013;34(2):155–161. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2012.728990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyng KM, Pedersen BS. Participatory design for computerization of clinical practice guidelines. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2011;44(5):909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.005. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbi.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulines E, Charpentier F. Pitch-synchronous waveform processing techniques for text-to-speech synthesis using diphones. Speech communication. 1990;9(5):453–467. [Google Scholar]

- Mulia N, Ye Y, Greenfield TK, Zemore SE. Disparities in alcohol_related problems among White, Black, and Hispanic Americans. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2009;33(4):654–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00880.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, Barry M, Col NF, Eden KB, Rovner D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews(3) 2009 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellisé F, Sell P. Patient information and education with modern media: The Spine Society of Europe Patient Line. European Spine Journal. 2009;18(SUPPL. 3):S395–S401. doi: 10.1007/s00586-009-0973-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spijkerman R, Roek MA, Vermulst A, Lemmers L, Huiberts A, Engels RC. Effectiveness of a web-based brief alcohol intervention and added value of normative feedback in reducing underage drinking: a randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12(5):e65. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaca F, Winn D, Anderson C, Kim D, Arcila M. Feasibility of emergency department bilingual computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment. Substance Abuse. 2010;31(4):264–269. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2010.514245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaca FE, Winn D, Anderson CL, Kim D, Arcila M. Six-month follow-up of computerized alcohol screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment in the emergency department. Substance Abuse. 2011;32(3):144–152. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.562743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Til JA, Drossaert CHC, Renzenbrink GJ, Snoek GJ, Dijkstra E, Stiggelbout AM, Ijzerman MJ. Feasibility of web-based decision aids in neurological patients. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare. 2009;16(1):48–52. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.001012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen PY, Bakken S. Review of health information technology usability study methodologies. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2012;19(3):413–422. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2010-000020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]