Abstract

This paper draws on original survey data to assess the prevalence of perceived discrimination among Latin American immigrants to Durham, NC, a “new immigrant destinations” in the Southeastern United States. Even though discrimination has a wide-ranging impact on social groups, from blocked opportunities, to adverse health outcomes, to highlighting and reifying inter-group boundaries, research among immigrant Latinos is rare, especially in new destinations. Our theoretical framework and empirical analysis expand social constructivist approaches that view ethnic discrimination as emerging from processes of competition and incorporation. We broaden prior discussions by investigating the specific social forces that give rise to perceived discrimination. In particular, we examine the extent to which perceptions of unequal treatment vary by gender, elaborating on the situational conditions than differentiate discrimination experiences for men and women. We also incorporate dimensions unique to the contemporary Latino immigrant experience, such as legal status, family migration dynamics, and transnationalism.

Keywords: Hispanic, immigration, discrimination, new destinations

It is difficult to overstate the impact of immigration on U.S. society. Latin America-U.S. migration grew 252 percent between 1990 and 2010 alone, with the immigrant Latino population reaching 21.2 million. This inflow was central to making Latinos the largest minority group in the United States today. Moreover, the impact of immigration is increasingly felt across a wider geographic area. Once largely confined to a handful of receiving states, primarily in the Southwest, Latino immigrants have increasingly dispersed to “new destinations” throughout the country, especially in the Southeast and Midwest (Marrow 2009; Oropesa & Jensen 2010). Many of these areas have experienced exponential growth in their Latino populations, transforming the racial and ethnic composition of local populations in the span of twenty years.

The scope and dispersion of the Latino immigrant population has generated intense interest and debate about their prospects for incorporation into U.S. society. On the one hand, a large body of research has suggested that classical assimilation paradigms developed to explain the experience of white ethnic immigrants during the last major wave of immigration do no hold for non-European groups. Instead, they argue that persistent discrimination against racialized minorities results in segmented assimilation (Portes and Rumbaut 1996), in which Latinos incorporate into disadvantaged minority communities, with social mobility blocked for generations (Telles & Ortiz 2008). However, while acknowledging the continuing force of racial discrimination in contemporary society, another group of scholars argues that assimilation is still the most powerful metaphor for the immigrant experience today (Alba & Nee 2003), and a growing body of research suggests that social mobility among Latinos, both within and across immigrant generations, has been substantial (Parrado & Morgan 2008; Smith 2003; Waters & Jiménez 2005; White & Glick 2009).

While experience with discrimination is central to the debate between segmented and new assimilation paradigms, it has not figured prominently in analyses of Latino incorporation (National Research Council 2006; Oropesa & Jensen 2010). This is limiting since numerous studies have documented the negative impact of ethnic discrimination on personal well-being, including its role in restricting socioeconomic opportunities (Bean and Stevens 2003; Portes & Rumbaut 2006) and undermining health (Ornelas, Eng, and Perreira 2011), especially mental health (Finch, Kolody, & Vega 2000). Perceptions of unequal treatment stemming from actual or perceived discrimination also increase awareness among minority group members of negative stereotypes held about them and heighten the social distance separating them from the American “mainstream,” making the social forces affecting perceptions of discrimination central to the process by which immigrants come to define themselves in ethnic terms (Golash-Boza & Darity 2008; Portes & MacLeod 1996; Wimmer 2013).

Moreover, while research on Latino experience with discrimination is lacking overall, studies on discrimination in new areas of immigrant destination are even more wanting (Baker, 2004; O’Neil & Tienda 2010; Oropesa & Jensen 2010). These areas are both unaccustomed to large immigrant populations, potentially heightening culture clash and exposure to discrimination, and lack an established ethnic community that would help migrants cope with exclusion. They are also characterized by a more rigid black-white divide and are potentially less tolerant of racial difference (Marrow 2009). Indeed, many states in the Southeast are at the forefront of passing state-level restrictive immigration legislation, in spite of relatively small immigrant populations. Thus, from a research perspective, emerging areas of destination can be considered an important laboratory for investigating the social processes fueling the development of perceptions of discrimination among immigrants.

Finally, the literature linking discrimination and immigrant incorporation has largely failed to take gender into consideration. Even though there is increasing recognition that migration is a gendered phenomenon, there has been limited attention to how perceptions of discrimination vary by gender, and how gender interacts with different settings to structure discrimination among Latino immigrants (Pager and Shepherd 2008). With female migration increasing, especially from Latin America, and immigrant women entering the labor market in growing numbers, this is a particularly pressing concern.

Drawing on original survey data, our analysis is thus guided by three main objectives. First, we assess the extent and prevalence of reported discrimination and its variation across social settings among Latin American immigrants to Durham, NC, a new immigrant destination. In particular, we examine the social forces predicting when and under what conditions perceptions of discrimination emerge. Second, we broaden prior theoretical discussions by explicitly investigating the role of gender in shaping perceptions of discrimination, elaborating on the unique situational conditions than differentiate the perceptions of ethnic discrimination between immigrant men and women. Finally, we incorporate into the analysis dimensions that are unique to the contemporary experience of Latino immigrants in the United States and have not received considerable attention, such as legal status, family migration dynamics, and transnationalism.

Theoretical background

Racial and ethnic discrimination has been a pervasive feature of the U.S. social order, and the topic has long been central for understanding the social mobility of minority group members, including immigrants. Discrimination was recognized as an obstacle to immigrant incorporation even within classical assimilation theory. Early writers such as Park and Burgess (1921), Warner and Srole (1945), and others argued that for racial minorities discrimination would hinder and slow the process of assimilation. However, the canonical formulation of assimilation theory tended to emphasize the inevitability and uni-directionality of assimilation, with the absence of discrimination representing the universal and final stage (Oropesa & Jensen 2010). Incorporating decades of multicultural and critical race theory critiques of classical assimilation, Portes and colleagues (1996) argued that for non-white migrants the experience with assimilation is segmented; conditions in the country of origin interact with those in the receiving society to offer multiple pathways of incorporation, including assimilation into the middle class, the perseverance of ethnic niches, and downward mobility into a minority “underclass.” Again, discrimination is central to the theory as the latter two pathways were argued to be more common for racial minorities who found their mobility blocked by discrimination (Portes & Rumbaut 2006). More recently, Alba and Nee (2003) have attempted to adjudicate between these two perspectives. They argue for a more dialectic approach that avoids the ethnocentric assumptions of classical assimilation theory and recognizes the continuing force of discrimination on contemporary immigrants, and yet also acknowledges the very real socioeconomic progress and incorporation that characterizes the post-civil rights era.

The debate over the extent to which discrimination will determine the path of incorporation for the latest waves of Latino immigrants focuses implicitly on actual discrimination against Latinos and other racial minorities. Much of this work centers on analyses of educational and labor market outcomes, and attempts to infer the importance of discrimination from the residual inequality between whites and minorities after accounting for human capital and other background characteristics. However, a related vein of research examines discrimination not only as an impediment to mobility but also as a reflection of group position within society. Much of this work focuses on perceptions of discrimination, and how they relate to the ethnic identity and the boundaries between groups (Nagel 1994; Wimmer 2013). Perceived discrimination presumably reflects an actual incident, but is also shaped in important ways by the ideology, identity, and worldview of the subject. As such, perceived discrimination is a critical barometer of social incorporation that can add an important dimension to the burgeoning literature on socioeconomic incorporation.

The rift in theories on the nature of assimilation for non-white immigrants is paralleled by competing views of the conditions that give rise to perceived discrimination. Classical assimilation theory relied on primordialist notions of ethnicity and group membership and viewed discrimination as the natural by-product of cultural differences, especially language and customs, between dominant and minority groups. According to this view, the cultural and behavioral attributes that immigrants bring with them from their countries of origin are at the root of the forces producing discrimination and negative stereotypes from the native population. Acculturation, defined as the “change in cultural patterns to those of the host society” (Gordon 1964: 71), was regarded as the first stage in the process of immigrant assimilation, necessary to attenuate negative stereotypes and treatment. Variation in immigrants’ exposure to discrimination was viewed as a function of immigrants’ degree of acculturation, and was expected to fall as immigrants approximated the attitudes and behaviors of the dominant group. Thus, while initial exchanges between immigrants and natives engender animosity, these tensions decline as newcomers learn English, adopt native customs, and gain in educational and occupational attainment (Yinger 1985).

Starting around the 1960s a different conceptualization of ethnicity emerged, which prompted a radically different view of the nature of discrimination. Rather than a rigid attribute of immigrants themselves, this perspective views ethnicity as a social construction emanating from the actions of individuals and groups as they define themselves and others in ethnic terms (Nagel 1994). Perceptions of discrimination among minority groups, according to this view, are a reflection of processes of ethnic boundary formation rather than the natural outcome of disparate cultural traits (Olzak 1992; Portes 1984; Wimmer 2013). The social constructivist view of ethnicity shifts the focus from the traits and behaviors that block acceptance into the American mainstream to the ethnic boundaries that define groups and the experiences of minorities themselves for understanding perceptions of discrimination. According to this view ethnicity is reactive (Olzak 1992; Portes 1984), and perceptions of discrimination emerge as immigrants confront inequalities in power, income, and social standing and resist the negative stereotypes held by the dominant group. Rather than declining with incorporation, perceived discrimination is redefined as a central component of the immigrant experience that often becomes more salient as contacts and competition with natives increase (Massey & Sanchez 2010; Portes & Bach 1985; Portes & Rumbaut 2006). As a result, the same personal resources that facilitate socioeconomic progress, such as English competency, lengthier U.S. residence, and education, also enhance competition between immigrants and natives, making newcomers more aware of inequalities in group position that translate into increased perceptions of discrimination and the construction of negative personal experiences in ethnic terms. In this process, occupational attainment is of particular significance since as immigrants move beyond their occupational niches and begin to threaten the status and privilege of the dominant group, they are expected to perceive increased exclusionary treatment.

Even though the social constructivist view has arguably become the dominant framework for understanding ethnic experiences, including discrimination, several factors highlight the continued relevance of the discussion. First, the rapid growth of Latin American immigration in recent decades has heightened ethno-racial tensions, as evidenced in nativism in public and occasionally even academic discourse. Fueled by the images of immigrant “invasion” (Chavez 2008), several commentators have stressed immigrants’ attachment to their foreign cultures as threatening to fragment the social fabric of the United States (Huntington 2004). From this perspective the negative treatment of immigrants arises from the dominant group’s reaction to and self-defense against immigrants’ clashing cultural traits.

Even outside of the nativist response, the scope and continuity of Latin American migration has prompted new debate about the sources of ethnic tensions and discrimination (Alba & Nee 2003). In the redefined version of assimilation theory group boundaries are more often explained as the product of immigrants’ cultural traits rather than competition. Alba, for instance, traces ethnic differences to cultural resources and argues that “groups that have a greater supply of cultural resources provide their members with more material to stimulate a sense of identity” (1990: 121). Implicit in this view is the idea that these cultural traits are central for understanding dominant group’s response to newcomers. For example, Jiménez refers to cultural symbols and practices as “ethnic raw materials” and argues that when they are lacking “ethnicity takes on a purely symbolic form and is not well integrated into an individual’s overall identity” (2010: 102). As applied to the Mexican-American experience the assumption is that immigrants provide such ethnic raw materials with continued immigration becoming the main force exposing the group to exclusion: “Mexican Americans are never the intended targets of nativist expressions. Their immigrant coethnics are” (2010: 143).

In spite of the continued relevance of the topic, research evaluating the social conditions that engender perceived discrimination among Latino immigrants is rare and Latinos have not figured prominently in the literature on discrimination (Oropesa & Jensen 2010: 277). With national-level survey data showing that as many as 30 percent of Latinos report having perceived day-to-day discrimination (Perez et al. 2008), more work on the topic is needed, particularly in new destinations where qualitative studies have described extensive feelings of exclusion among Latino immigrants (Mahler 1995; Marrow 2011).

Moreover, Brubaker and colleagues (2004) have argued that social constructivist approaches have grown complacent with their success despite the fact that the processes leading to group identifications are not well understood. Instead of simply asserting that ethnicity is socially constructed they argue that studies need to more precisely specify how and when people perceive others as different and experience the world in ethnic terms. Especially important for this extension is the ability to better identify the specific contexts and particular situations that crystallize ethnic experiences, including perceptions of discrimination. Such an approach will not only illuminate the mechanisms producing discrimination but also help link macro-level group outcomes with micro-level individual processes.

One of the most serious gaps in social constructivist approaches is the lack of sufficient attention to the role of gender in structuring perceptions of discrimination. Immigration has long been recognized as a highly gendered phenomenon (Hondagneu-Sotelo 1994). This recognition parallels developments in the literature on gender and race that has elaborated on the notion of intersectionality to highlight how multiple social inequalities, such as race, class, and gender, interact in a manner that makes the experience of minority women not simply additive, but qualitatively different from that of their male counterparts (Collins 2000). Applying the approach to interpersonal racial discrimination, Harnois and Ifatunji (2010) showed that while some discriminatory practices similarly affect both black men and women, others are highly gendered. While nativity is rarely explicitly incorporated into the intersectionality approach, the critique offers valuable lessons for social constructivist approaches to perceived discrimination. Prior formulations rightly highlighted the labor market as a central sphere for contact and competition between immigrants and natives. However, labor markets are highly segregated by both national origin and gender, and there is often little overlap in the occupational niches of immigrant men and women. Moreover, immigrants interact with the mainstream in a multiplicity of settings outside of work that are also highly gendered. For instance, minority men have a very different relationship with the police than their female counterparts, and women more often engage in school and medical settings than men. Thus, in investigating gender differences in immigrants’ experiences with discrimination it is important not only assess whether their prevalence varies by gender, but also whether the determinants of these experiences are different for men and women, and more importantly, whether and how perceived discrimination varies across different social settings and gender simultaneously.

In addition, the literature on immigrant adaptation has emphasized the context of reception as a key determinant of immigrant incorporation (Portes and Rumbaut 1986). One critical aspect of this context that sets today’s Latino immigrants sharply apart from their European predecessors is the legal and policy climate. The vast majority of recently arrived low-skill labor migrants from Latin America enter the U.S. illegally, and undocumented status has become both a major form of social exclusion and the subject of increasingly vitriolic public rhetoric (Menjivar & Abrego 2012). Despite its importance, it remains an open question as to whether and how legal status affects perceived discrimination. From an assimilation perspective, the erosion of barriers associated with legal residence could reduce perceptions of social distance and discrimination. The opposite could be expected from perspectives stressing ethnic competition; to the extent that legal residence expands labor market opportunities and contact with the dominant group it could enhance immigrants’ exposure to discrimination.

Similarly, there has been insufficient attention to the impact of social support and the unique family dynamics associated with migration on perceived discrimination. Legal regulations as well as the historical origins of Latin American migration flows have resulted in a pattern of migration that involves considerable family separation, typically when husbands migrate and live alone in the United States for a period until they are either established enough to send for their families or return to their countries of origin. Other families migrate together and do not experience separation. These migration dynamics are potentially important to the social construction of ethnic experiences and perceived discrimination, as they both reflect different levels of integration in U.S. society and structure the kinds of interactions immigrants have with their host environment. One could argue that the reconstruction of families either during or after migration is a powerful marker of incorporation. To the extent that it can buffer negative reactions from natives, migrating as a family might reduce exposure to discrimination. On the other hand, family migration might push migrants to search for opportunities outside their ethnic niches, in search of better housing, schools, and jobs, heightening exposure to discrimination.

In addition to family dynamics, migrants also vary in the extent to which they join social networks already established in the United States, and in their engagement with more formal sources of support, particularly the church, both of which could shape experiences with discrimination. Migrants who have extensive networks of extended family and friends at arrival are likely to adapt more quickly, as they have access to more information on quality job opportunities and housing (Flippen 2012, 2013). Likewise, Hagan (2008) illustrated the importance of religious beliefs and participation during all stages of Latin American migration to the United States, from the decision to migrate to the process of incorporation. Specific expectations about the connection between religious involvement and perceptions of discrimination, however, have not always been explicit. Classic accounts have treated religious participation primarily as a way of coping with the challenges of adaptation to a new environment. They tended to single out the psychological benefits of religious involvement as providing solace and refuge against the traumas of immigration. The benefits were not just psychological; religious participation also provided newcomers with resources and contacts that facilitated their socioeconomic incorporation (Hirschman 2004). However, religious institutions can also be sites of ethnic conflict. Hirschman recognizes this possibility, noting that “generalized hostility from the majority population may have contributed to the American tradition of new immigrant communities founding their own ethnic churches” (2004: 1223). Because religious institutions have a long history of advocating for their congregations, they may also actively shape how immigrants perceive treatment from the larger society.

And finally, researchers have highlighted that current migration to the United States, especially from Latin America, occurs under conditions of transnationalism (Levitt & de la Dehesa 2003; Portes et al. 1999). While definitions vary, transnationalism centers on processes of exchange, connection, and mobility that cross national borders. While circular migration and regular visits are not necessarily new, the notion of transnationalism highlights that being connected to several places can have a direct impact on activities and identities in a manner that was not recognized in prior analyses. Cross-border connections have been particularly salient in the Latin American, especially Mexican, case which has been characterized, at least until recently, as a very dynamic flow with considerable mobility back and forth. The role of transnationalism in affecting ethnic experiences has not been systematically addressed. Consistent with primordialist views, Yinger has argued that for Mexicans “the ease of returning to the homeland and its frequency are clearly dissimilative” (1994:60). Especially regarding acculturation, regular contacts with sending countries could prevent immigrants from adopting the customs and manners of the host society. Again, opposite expectations derive from the social constructivist approaches. To the extent that immigrants keep close ties with sending areas their behaviors remain oriented towards the country of origin, they could be relatively insulated from perceptions of discrimination in host societies.

Data and methods

We investigate these issues with data from the Gender, Migration, and Health among Hispanics study (Parrado, McQuiston, and Flippen 2005; Flippen and Parrado 2012). The project collected a community based participatory survey in the Durham, Chapel Hill, and Carrboro metropolitan area of North Carolina (for the sake of expediency referred to as “Durham,” where the majority of respondents lived) between June 2006 and March 2007. Durham offers a valuable vantage point from which to explore new immigrant destinations. Growth of the high-tech sector during the 1990s spurred a boom in business and residential construction, heightening demand for construction and other semi-skilled laborers, as well as for domestic work and other service employment for the growing class of professionals in the area. The result of these forces was dramatic. In 1990, less than 2,000 foreign born Latinos were residing in the area, but by 2010 the number had reached close to 40,000, or 12 percent of the total population.

The highly marginalized position of Latino immigrants in contemporary U.S. society presented unique challenges to collecting a locally representative sample. The study relied on a combination of Community Based Participatory Research (CBPR) and targeted random sampling to overcome these difficulties. CBPR is a participatory approach to research that incorporates members of the target community in all phases of the research process (Israel et al. 2005). In our case, a group of 14 community members assisted in the planning phase of the study, survey construction and revision, and devising strategies to boost response rates and data quality. In addition, CBPR members were trained in research methods and conducted all surveys. Finally, through ongoing collaborative meetings, they were also influential in the interpretation of survey results and giving culturally grounded meaning to the findings.

At the same time, the relatively recent nature of the Hispanic community in Durham rendered simple random sampling prohibitively expensive. We therefore employed targeted random sampling techniques (Waters & Bernacki, 1989). Based on our knowledge of the community, we identified 49 apartment complexes and blocks that house large numbers of immigrant Hispanics. We then collected a census of all the apartments in these areas and randomly selected individual units to be visited by interviewers. Although our survey may have been less likely to capture well-established immigrants, this method was far superior to nonrandom methods of recruitment such as snowball or convenience sampling. Overall, information was collected from 929 and 708 Latin American male and female immigrants, respectively. The male and female samples were independently drawn. To evaluate potential bias arising from targeted random sampling, we compared our sample with data from the 2000 Census. The results show no statistically significant differences in main socio-demographic characteristics such as age, education, employment status, wages, and time in the United States (Parrado, McQuiston, and Flippen 2005).

Variable definitions and descriptive results

Our analysis centers on perceptions of discrimination and their variation across settings. There has been a long-standing interest in the question of discrimination in the social and social psychological sciences which has resulted in numerous techniques to identify its presence and document its effects, ranging from simple questionnaires to experimental designs (Page and Shephard 2008). No method is without limitations. Especially in studies of perceived discrimination, it is important to note that the same event or treatment can be interpreted in different ways depending on the characteristics of the subject, resulting in potential under- and over-estimation of actual discrimination (see Pager and Shepherd 2008 for a review). Regardless of the degree of correspondence of actual and perceived discrimination, the perceptions themselves have been shown to have measurable effects. Several meta-analyses of social and psychological studies have documented the detrimental effects of perceptions of racial and ethnic discrimination on mental and physical health outcomes as well as their effect on heightened stress responses and increases in health risk behaviors (Pascoe and Richman, 2009; Pieterse et al. 2012). In addition, perceptions, irrespective of their factuality, directly connect with the social construction of group boundaries and the cognitive processes that undergird the framing of personal experiences in ethnic terms (Brubaker, 2004; Weimer 2013).

We measure perceived discrimination with the Experiences of Discrimination (EOD) instrument proposed by Kreiger and colleagues (1990; 2005), which is also available in Spanish. It asks whether a person has ever2 experienced discrimination, been prevented from doing something, or been hassled or made to feel inferior because of their race, ethnicity, or color in seven different settings: school, obtaining a job or at work, renting a house, seeking medical care, in a store or restaurant, on the street or in a public setting, and from the police or in the courts. We restricted the time frame to experiences with discrimination since arriving to Durham. Responses were coded yes or no, and aggregated across situations to produce an EOD Index (EODI) that ranges from zero to seven and is interpreted as the number of settings where immigrant Latinos perceived discrimination. Separate responses to particular settings are used to assess the extent to which perceptions vary across types of interactions and by gender.

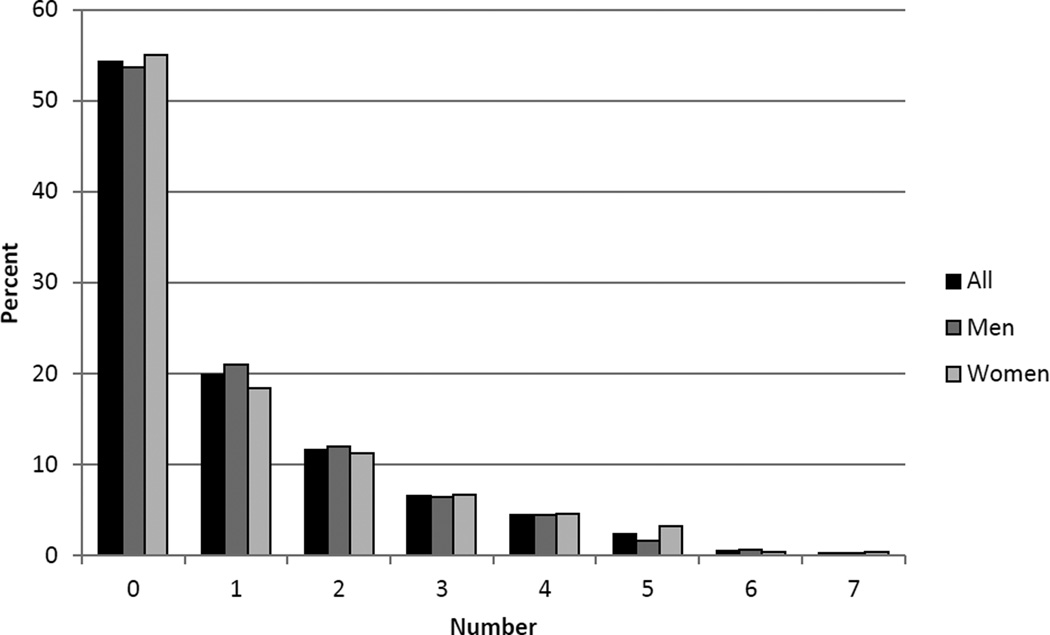

Figure 1 reports the distribution of the EODI by gender in our sample. Less than 55 percent of men and women in the sample report no incidents of perceived discrimination in any setting; roughly 20 percent reported perceiving discrimination in just one setting and 10 percent in two. While gender differences in the total number of contexts where immigrants experience discrimination are modest, when we disaggregate by setting in Table 1 clear differences emerge. For both men and women, the top settings for experiencing discrimination are at work and in public places. However, men are significantly more likely than women to perceive discrimination at work (25 vs. 22 percent), with the police (12 vs. 7 percent), and in restaurants (18.2 vs. 13.8 percent). Women, in turn, report greater discrimination than men at school (9 vs. 3 percent) and in hospitals (17 vs. 5 percent).

Figure 1.

Perceived Discrimination Index by Gender

Table 1.

Despcriptive statistics for dependent variables: Perceived discrimition index (PDI) an across contexts

| All | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average PDI score | 1.0 | (1.4) | 1.0 | (1.3) | 1.0 | (1.4) |

| By context (%) | ||||||

| School | 6.0 | 3.2 | 9.4 | |||

| Work | 23.5 | 25.2 | 21.5 | |||

| Renting | 11.0 | 10.4 | 11.7 | |||

| Hospital | 10.4 | 5.0 | 16.9 | |||

| Restaurant | 16.2 | 18.2 | 13.8 | |||

| In public | 20.8 | 21.4 | 20.1 | |||

| Police | 9.7 | 11.9 | 7.1 | |||

| N | 1709 | 929 | 780 |

Bolded coefficients indicate signficant gender differences at p<0. 05

Table 2 lists the explanatory variables in the analysis together with their descriptive statistics by gender. While Latin American immigrants are often lumped together as “Hispanic,” they hail from a number of different countries, each with unique histories and migration systems. We therefore include mutually exclusive dummy variables indicating whether the respondent was born in Mexico, Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, or another Latin American country. Close to 70 percent of the Durham Latino immigrant community is Mexican, 15 percent is Honduran, and around 6 percent each is from El Salvador and Guatemala. We also include two indicators of pre-migration human capital: rural origins and education. The 22 percent of our sample who herald from rural areas could be less well prepared for adapting to life in the United States than those from small towns (38 percent) or cities (40 percent). Education levels are relatively modest, with the average migrant completing 7.7 years of formal schooling. None of these characteristics differ significantly by gender.

Table 2.

Despcriptive statistics: Explanatory variables

| Full Sample | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of origin (%) (ref: Mexico) | ||||||

| Honduras | 15.3 | 15.9 | 14.6 | |||

| El Salvador | 6. 0 | 5. 5 | 6.5 | |||

| Guatemala | 6. 3 | 7.1 | 5.4 | |||

| Other | 1. 6 | 1.0 | 2.3 | |||

| Human capital | ||||||

| Rural/Urban origin (%) (ref : Rancho) | ||||||

| Ciudad | 39.3 | 33.7 | 46.2 | |||

| Pueblo | 37.6 | 37.8 | 37.3 | |||

| Years of education (mean) | 7.7 | (3. 4) | 7.3 | (3. 3) | 7.8 | (3. 6) |

| Acculturation/competition | ||||||

| Age at arrival | 25.3 | (7. 6) | 25. 3 | (7. 6) | 25.3 | (7. 5) |

| Years in Durham | 4.4 | (3. 6) | 4.5 | (3. 8) | 4.3 | (3. 3) |

| Internal U. S. migrant | 33.6 | 38.0 | 28.3 | |||

| Speaks some English | 54.6 | 64.4 | 42.9 | |||

| Documented | 8.3 | 8.6 | 7.8 | |||

| Occupational Attainment (Percent of Durham-years working in) | ||||||

| Non-niche occupations | 18. 1 | 20.4 | 15.5 | |||

| Works mostly with Latinos | 48.9 | 63.0 | 48.4 | |||

| Construction | 38.0 | |||||

| Restaurant | 11.2 | |||||

| Gardening | 9.4 | |||||

| Agriculture | 4. 2 | |||||

| Not working | 33.5 | |||||

| Restaurant | 19.9 | |||||

| House/ Hotel cleaning | 17.8 | |||||

| Laundry | 3.7 | |||||

| Factory | 7.6 | |||||

| Childcare | 2.0 | |||||

| Family dynamics and Social support (%) | ||||||

| Marital status and migration(ref : Single) | 21.9 | 24.1 | 18.0 | |||

| Migrated single and married in U.S. | 26.8 | 20.5 | 34.4 | |||

| Married w/spouse at origin | 19. 1 | 34.1 | 1.2 | |||

| Migrated with Spouse | 32.3 | 21.3 | 46.5 | |||

| Has a school aged child | 26.2 | 18.7 | 35.1 | |||

| Had f amily in Durham at arrival | 69.8 | 66.4 | 73.8 | |||

| Had friends in Durham at arrival | 41.6 | 49.4 | 32.3 | |||

| Attends Church | 61.3 | 55.5 | 67.9 | |||

| Transnationalism | ||||||

| Number of visits to country of origin | 5.6 | (0. 9) | 5.6 | (0. 9) | 5.7 | (0. 9) |

| Return plans (%) (ref . Unclear) | ||||||

| In less than 2 years | 18.9 | 23.8 | 13.1 | |||

| Not planning on returning | 25.3 | 32.3 | 16.9 | |||

| N | 1709 | 929 | 780 | |||

Bolded coefficients indicate statistically signficant gender differences at p<0.05

We also include a number of immigration characteristics that correspond to measures associated with acculturation as well as contact and competition. The first is age at arrival, which was 25, on average, among the men and women in our sample. We also include the number of years in Durham. Reflecting their recent arrival, the average length of stay in the area is a relatively short 4.4 years, with no significant differences by gender. We also include a dummy indicator of whether respondents had lived in another U.S. location prior to arriving in Durham, as an indicator of additional U.S. experience; close to 34 percent of the sample had U.S. experience outside of Durham. The representation is much higher among men than women (38 vs. 28 percent), reflecting the common practice of married men migrating alone and sending for their wives and families once they are established. Finally, we also include a dummy indicator of whether the respondent spoke at least some English, as opposed to none at all. Only 55 percent for the sample reported speaking some English, with share substantially higher among men than women (64 vs. 43 percent).

In addition, our analysis includes a number of other, potentially important, markers of acculturation/competition not systematically considered in prior studies. First among them is legal status. Reflecting the undocumented nature of labor migration from Latin America, only 8 percent of the men and women in our sample reported having legal authorization to work. Family migration dynamics are captured by four mutually exclusive dummy variables that indicate whether the respondent migrated single and remained single until interview; migrated single and married in the United States; migrated after marriage while their spouse continued to reside in the country of origin; or migrated after marriage with both partners living in the United States. The descriptive results document the significant interaction between gender and family migration dynamics. Around 24 percent of men and 18 percent of women migrated to Durham single and remained single at interview. While 20.5 percent of men migrated single and married in the U.S., the prevalence is 34.4 percent among women. Over one-third (34.1 percent) of men in Durham are married with their spouse in country of origin. The practice is negligible among women (1.2 percent). Finally, while only 21.3 percent of men migrated jointly or reunited with their wives after migration, fully 46.5 percent of women did so.

Since employment instability is common among immigrants in Durham (self-identifying reference), and because experiences of discrimination reflect accumulated experiences over time we assess labor market interactions using the detailed employment histories in our survey to construct a measure of the proportion of person-years in Durham working in particular occupations. We also investigated models that included first occupation as a predictor. Results (available upon request) are not substantively different. As seen in Table 2, Latino immigrants are highly segregated in Durham’s labor market, and with the exception of restaurant work there is little overlap in the occupations held by men and women. The vast majority of men work in just three fields: construction, restaurant work, and gardening. Only 20.4 percent of person-years are spent outside of these niches among men, in jobs as varied as retail, DJs, and military service. The occupational distribution among women is equally concentrated, though women spent on average 30 percent of their time in Durham not working, a pattern that does not exist for men. Among those who ever worked in the area, six occupations capture 83 percent of the labor force participation: restaurant work, cleaning, laundry, childcare, factory work, and retail. A scant 11.2 percent of time in Durham was spent working outside of these niche occupations among immigrant Latinas, in jobs that ranged from secretaries, to bank tellers, to hair dressers. To further assess variation in the extent of ethnic enclosure we also include a dummy variable indicating whether the majority of co-workers were Latinos. Among men 63 percent reported working in primarily Latino environments, while for women the proportion is 48 percent.

We also account for family responsibilities and the availability of social support by including dummy indicators of whether the respondent had a school age child at interview, and family or friends when they first arrived to Durham. Men are less likely to have school aged children than women (18.7 versus 35.1 percent). Similarly, they are less likely to have had family at arrival than women (66 vs. 74 percent), but were more likely to have had friends (50 vs. 32 percent). Organizational support is captured by a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent regularly attended religious services in Durham. Over 61 percent of the sample reported regular church attendance, though the number is significantly higher among women than men (68 vs. 56 percent).

Transnational conditions are measured by a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent visited their country of origin since arrival. Again reflecting the legal restrictions on migration, only six percent of our sample reported visiting their home countries since arriving to Durham. In addition, we include three mutually exclusive dummy variables measuring migration intentions, namely whether the respondent intended to return to their country of origin within two years, whether they did not intend to return, and whether they were unsure. While most migrants were either unsure about their intentions (44.2 percent) or hoped to settle in the United States (25.3 percent), nearly 19 percent planned to leave in less than two years, with considerably variation by gender. Specifically, men were more likely than women to report that they intended to return in the short term (24 vs. 13 percent), though they were also more likely to report intending to remain (32 vs. 17 percent). Women overall were far more uncertain about their future plans than were men.

Results

Variation in the number of settings where immigrant Latinos perceive discrimination

Table 3 reports the coefficients from negative binomial regression models predicting the EODI by gender. Negative binomial models are well suited for situations where the dependent variable is a count and contains a large number of zero values. Results document no differences in EODI according to gender, national origin, or urban upbringing. Education, on the other hand, does significantly predict EODI scores, and does so in a manner consistent with social constructivist perspectives. That is, each additional year of education increases the EODI by 3 percent (1-exp(0.033)). Predicted results show that for an immigrant with average characteristics moving from 6 to 12 years of education raises the EODI from 0.52 to 0.63, or 20 percent.

Table 3.

Negative binomial models predicting PDI by gender (Standard errors in parentheses)

| Full Sample | Men | Women | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (1=Female) | 0.096 | (0. 094) | --- | --- | ||

| Country of origin (ref:Mexico) | ||||||

| Honduras | 0.006 | (0.06) | −0.047 | (0.141) | 0.000 | (0.163) |

| El Salvador | 0.102 | (0.158) | 0.107 | (0.225) | 0.164 | (0.225) |

| Guatemala | −0.108 | (0.161) | 0.006 | (0.196) | −0.412 | (0.286) |

| Other | 0.041 | (0.284) | −0.166 | (0.526) | −0.061 | (0.355) |

| Rural/Urban origin (ref:Rancho) | ||||||

| Ciudad | 0.051 | (0.102) | 0.125 | (0.134) | −0.030 | (0.162) |

| Pueblo | −0.022 | (0.099) | 0.132 | (0.124) | −0.245 | (0.165) |

| Years of education | 0.033** | (0.012) | 0.029* | (0.016) | 0.033* | (0.018) |

| Acculturation/competition | ||||||

| Age at arrival | −0.012** | (0.006) | −0.017** | (0.008) | −0.006 | (0.008) |

| Years in Durham | 0.036** | (0.012) | 0.042** | (0.015) | 0.036** | (0.019) |

| Internal U. S. migrant | 0.178** | (0.084) | 0.223** | (0.117) | 0.191* | (0.130) |

| Speaks some English | 0.213** | (0.084) | 0.060 | (0.117) | 0.346** | (0.124) |

| Documented | 0.056 | (0.142) | 0.016 | (0.194) | 0.110 | (0.216) |

| Occupational Characteristics | ||||||

| Non-niche occupations | 0.259** | (0.114) | 0.181 | (0.154) | 0.747** | (0.228) |

| Latino worksite | −0.141 * | (0.078) | −0.190* | (0.106) | −0.227* | (0.128) |

| Construction(ref.) | ||||||

| Restaurant | --- | −0.172 | (0.199) | --- | ||

| Gardening | --- | −0.140 | (0.214) | --- | ||

| Agriculture | --- | 0.369 | (0.362) | --- | ||

| Not working (ref.) | ||||||

| Restaurant | --- | --- | 0.590** | (0.208) | ||

| House/Hotel cleaning | --- | --- | 0.345* | (0.215) | ||

| Laundry | --- | --- | 0.075 | (0.413) | ||

| Assembling at factory | --- | --- | 0.694** | (0.281) | ||

| Nanny | --- | --- | 0.054 | (0.571) | ||

| Family dynamics and Social support | ||||||

| Marital status and migration(ref:Single) | ||||||

| Married in U. S. | −0.204 | (0.100) | −0.365 | (0.239) | 0.030 | (0.165) |

| Married w/spouse at orig | 0.055 | (0.113) | 0.031 | (0.130) | −0.092 | (0.503) |

| Migrated with Spouse | −0.056 | (0.099) | 0.098 | (0.146) | 0.067 | (0.162) |

| Has a school aged child | 0.131 | (0.096) | 0.036 | (0.154) | 0.102 | (0.129) |

| Had family in Durham at arr | 0.026 | (0.083) | 0.138 | (0.108) | −0.145 | (0.133) |

| Had friends in Durham at ar | −0.011 | (0.078) | 0.013 | (0.100) | −0.085 | (0.123) |

| Attends Church | 0.149** | (0.079) | 0.194** | (0.099) | 0.091 | (0.132) |

| Transnationalism | ||||||

| Visits country of origin | 0.040 | (0.045) | 0.079 | (0.065) | 0.000 | (0.066) |

| Return plans (ref.Unclear) | ||||||

| In less than 2 years | −0.048 | (0.103) | −0.109 | (0.130) | 0.033 | (0.172) |

| Not planning | 0.104* | (0.088) | 0.185* | (0.109) | −0.051 | (0.146) |

| Intercept | −0.729** | (0.358) | −0.859* | (0.496) | −0.734 | (0.543) |

| Dispersion parameter | 1.106 | (0.096) | 0.948 | (0.120) | 1.138 | (0.144) |

| Log Likelihood | ||||||

| N | 1709 | 929 | 780 | |||

p <.10

p<.05

Bolded coefficients indicate signficant gender differences at p<0. 05

The effect of immigrant characteristics on perceived discrimination is also consistent with social constructivist perspectives. The number of perceived discrimination encounters is lower among those arriving at older ages (−0.012) and higher among those with longer lengths of stay in Durham (0.036). The effect is again sizeable. For the average immigrant, increasing time in Durham from 4 to 10 years is associated with a 25 percent higher EODI (0.52 vs. 0.65). Similarly, EODI is significantly higher among internal migrants (0.178), and those who speak English (0.213), though the effect of legal status was not significant.

Occupational attainment is also central to understanding Latin American immigrants’ perceptions of discrimination. In full sample models we include only whether or not respondents work in immigrant niches, and whether they report working primarily with other Latinos at their particular work site as explanatory variables. Again, consistent with social constructivist approaches that stress out-group interactions over cultural traits, result show that working outside of immigrant niches is associated with perceived discrimination in a greater number of settings (0.259), while working at predominantly Latino worksites is negatively associated with the EODI (−0.141). Family dynamics, social support, and transnationalism also have an impact on perceptions of discrimination. Both regular church attendance and the intention to remain in the United States are positively associated with EODI (0.149 and 0.104, respectively), again contradicting the idea that greater social integration results in less exposure to discrimination.3

While these models are informative, pooling men and women together misses potentially important variation in the mechanisms undergirding perceptions of discrimination. Accordingly, we estimated similar models separately by gender. Overall, results show the correlates of perceptions of discrimination to be fairly similar for men and for women. Factors such as education, time in Durham, internal migration, and working at predominantly Latino worksite have a similar effect on EODI for men and women. However, there are a number of noteworthy differences as well. For instance, while age at arrival negatively correlates with EODI for men, the effect is not significant for women. The opposite pattern is true for English skills, which positively predict EODI for women but not for men. Both of these effects could relate to sex differences in occupational niches. When women cannot communicate in English they tend to either not work or work in immigrant intensive niches (self-identifying reference), with little contact with non-Latino groups. English is less determinate of men’s employment and occupation (self-identifying reference), as construction and yard work generally involve teams of workers who can rely on coworkers to translate.

In a similar vein, the impact of regular church attendance also varies by gender. Church attendance is positively correlated with EODI among men but not women. For women, church attendance is nearly universal, and may not be associated with greater integration into U.S. society. For men, on the other hand, church attendance is often associated with the reformulation of social ties after migration, and thus could be more pertinent to the forces shaping perceived discrimination. In addition, the effect of migration intentions is also a significant predictor of EODI for men but not women, possibly due to the relative lack of variation among women, who are overwhelmingly uncertain about the possibilities of settlement and return. Among men, intended settlement is positively associated with the EODI.

And finally, occupational effects also vary considerably by gender. While both men and women who work primarily with other Latinos report less perceived discrimination than their peers in more integrated work environments, for men other occupational effects are slight. For women, on the other hand, EODI varies widely across occupations. Results suggest that virtually any type of labor market participation, whether it is in restaurants, factories, retail, or non-niche occupations, enhances EODI, reinforcing the idea that perceptions of discrimination develop in conjunction with increased participation in U.S. institutions.

Perceived discrimination by setting

The final set of analyses evaluate the social determinants of perceived discrimination by setting (i.e., with school, work, housing, hospitals, restaurants, public places, and the police). Table 4 reports results from logit models estimating whether respondents reported having suffered discrimination in each of the seven settings that compose the EODI. While we did not find gender differences in the aggregate EODI, there are considerable differences between men and women when we separate the analysis by setting. Compared to men, women reported greater experiences with discrimination in schools (1.14) and hospitals (1.46) and fewer experiences with discrimination at work (−0.18) and with the police (−0.48). Thus, even though overall number of settings exposing Latinos to perceptions of discrimination does not vary by gender the type of contacts producing those experiences is very different for men and women. A main implication is that while not working mitigates women’s exposure on some fronts, their greater interaction in school and medical settings counteracts this protective effect. At the same time, women’s lower level of public participation, especially driving, significantly protects them from police encounters and feelings of discrimination.

Table 4.

Coefficients from logistic models predicting perceived discrimination encounters in particular settings (Standard errors in parentheses)

| School | Work | Ranting | Hospital | Restaurant | Public | Police | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (1=Female) | 1.14** | (0.28) | −0.18* | (0.12) | −0.04 | (0.20) | 1.46** | (0.24) | −0.20 | (0.18) | 0.04 | (0.16) | −0.48** | (0.22) |

| Country of origin (ref: Mexico) | ||||||||||||||

| Honduras | −0.27 | (0.35) | 0.22 | (0.17) | 0.04 | (0.23) | 0.00 | (0.25) | −0.04 | (0.20) | −0.16 | (0.19) | 0.10 | (0.25) |

| El Salvador | 0.50 | (0.38) | 0.06 | (0.26) | 0.44 | (0.32) | 0.39 | (0.32) | −0.19 | (0.32) | −0.03 | (0.27) | 0.04 | (0.37) |

| Guatemala | 0.16 | (0.46) | −0.08 | (0.26) | 0.14 | (0.35) | 0.06 | (0.40) | −0.21 | (0.32) | −0.07 | (0.28) | −0.38 | (0.42) |

| Other | −0.26 | (0.69) | 0.16 | (0.46) | 0.43 | (0.59) | −0.27 | (0.60) | 0.06 | (0.54) | 0.22 | (0.46) | 0.42 | (0.60) |

| Human capital | ||||||||||||||

| Rural/Urban origin (ref: Rancho) | ||||||||||||||

| Ciudad | −0.20 | (0.29) | −0.10 | (0.16) | 0.22 | (0.23) | −0.13 | (0.23) | 0.45** | (0.20) | 0.17 | (0.18) | −0.01 | (0.23) |

| Pueblo | −0.39 | (0.30) | −0.17 | (0.16) | 0.25 | (0.22) | −0.23 | (0.23) | 0.20 | (0.20) | 0.10 | (0.17) | −0.09 | (0.23) |

| Years of education | 0.02 | (0.04) | 0.02 | (0.02) | 0.02 | (0.03) | 0.07** | (0.03) | 0.06** | (0.02) | 0.05** | (0.02) | 0.03 | (0.03) |

| Acculturation/ competition | ||||||||||||||

| Age at arrival | −0.02 | (0.02) | −0.01 | (0.01) | 0.02 | (0.01) | 0.01 | (0.01) | −0.03** | (0.01) | −0.03** | (0.01) | −0.04** | (0.01) |

| Years in Durham | 0.00 | (0.03) | 0.04** | (0.02) | 0.06** | (0.02) | 0.03 | (0.03) | 0.06** | (0.02) | 0.04** | (0.02) | 0.05** | (0.02) |

| Internal U.S migrant | 0.44* | (0.24) | 0.14 | (0.13) | −0.02 | (0.18) | 0.36** | (0.18) | 0.15 | (0.16) | 0.13 | (0.14) | 0.27 | (0.19) |

| Speaks some English | 1.08** | (0.27) | 0.14 | (0.14) | 0.11 | (0.19) | 0.06 | (0.19) | 0.06 | (0.16) | 0.49** | (0.14) | 0.45** | (0.21) |

| Documented | 0.52* | (0.35) | 0.38* | (0.22) | −0.52* | (0.35) | 0.00 | (0.31) | 0.12 | (0.27) | 0.08 | (0.24) | −0.24 | (0.32) |

| Occupational Characteristics | ||||||||||||||

| Non-niche occupations | 0.38 | (0.33) | 0.38** | (0.18) | 0.31 | (0.24) | 0.04 | (0.27) | 0.41** | (0.20) | 0.24 | (0.19) | 0.53** | (0.24) |

| Works mostly with Latinos | −0.41* | (0.23) | −0.26** | (0.12) | 0.05 | (0.17) | −0.06 | (0.18) | −0.22 | (0.14) | −0.27** | (0.13) | −0.22 | (0.18) |

| Family dynamics and Social support | ||||||||||||||

| Marital status and migration(ref: Single) | ||||||||||||||

| Married in U.S. | −0.19 | (0.28) | −0.37**) | (0.16 | −0.29 | (0.22) | 0.30 | (0.23) | −0.60** | (0.19) | −0.41** | (0.17) | 0.07 | (0.22) |

| Married w/spouse at origin | −0.78* | (0.47) | −0.07 | (0.17) | −0.50** | (0.25) | 0.38 | (0.29) | 0.34* | (0.20) | 0.16 | (0.18) | 0.27 | (0.24) |

| Migrated with Spouse | −0.16 | (0.29) | −0.19 | (0.16) | 0.08 | (0.21) | 0.25 | (0.23) | −0.12 | (0.18) | −0.06 | (0.17) | 0.02 | (0.24) |

| Has a school aged child | 0.13 | (0.27) | 0.07 | (0.16) | 0.11 | (0.20) | 0.24 | (0.20) | 0.02 | (0.19) | 0.17 | (0.16) | 0.22 | (0.22) |

| Had family in Durham at arrival | 0.04 | (0.25) | 0.12 | (0.14) | −0.21 | (0.18) | −0.24 | (0.19) | 0.04 | (0.16) | 0.13 | (0.14) | 0.05 | (0.19) |

| Had friends in Durham at arrival - | 0.26 | (0.24) | −0.04 | (0.12) | 0.06 | (0.17) | −0.04 | (0.18) | −0.10 | (0.15) | −0.01 | (0.13) | 0.20 | (0.18) |

| Attends Church | 0.14 | (0.24) | 0.30** | (0.13) | 0.17 | (0.18) | 0.03 | (0.19) | 0.08 | (0.15) | 0.20** | (0.13) | −0.01 | (0.18) |

| Transnationalism | ||||||||||||||

| Visits country of origin | 0.07 | (0.14) | 0.05 | (0.07) | 0.20* | (0.12) | −0.03 | (0.10) | 0.13 | (0.09) | 0.05 | (0.08) | −0.08 | (0.10) |

| Return plans (ref. Unclear) | ||||||||||||||

| In lessthan 2 years | −0.14 | (0.34) | 0.00 | (0.16) | −0.38* | (0.25) | −0.18 | (0.26) | 0.10 | (0.19) | 0.12 | (0.17) | −0.39* | (0.26) |

| Not planning | −0.10 | (0.26) | 0.12 | (0.14) | 0.19 | (0.18) | 0.09 | (0.20) | 0.19 | (0.16) | 0.23* | (0.15) | 0.01 | (0.20) |

| Intercept | −3.98** | (1.12) | −1.60** | (0.58) | −4.33**) | (0.90 | −3.97** | (0.79) | −2.46** | (0.72) | −2.11** | (0.62) | −1.73** | (0.78) |

| Likelihood ratio Chi-Square | 88.0 | 42.8 | 37.3 | 98.2 | 57.0 | 70.0 | 64.4 | |||||||

| N | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | 1709 | |||||||

p<10

p<.05

Table 4 also highlights variation in the social forces shaping perceived discrimination across settings. Education has a positive effect on perceived discrimination in all contexts, but the effect is sizeable and statistically significant only in interactions at hospitals, restaurants, and other public places. The effect of years in Durham is also positive and consistent across settings but particularly strong for renting and interactions with the police. Internal migrants and those who speak English are particularly prone to report discrimination in school settings.

Interestingly, while documentation did not affect the EODI overall, it significantly predicts perceived discrimination at school and work. Result show that having legal documentation increases perceptions of discrimination in these two contexts. At work, Massey and Bartley (2005) have argued that as entire fields move to subcontracting to avoid the sanctions associated with hiring undocumented workers, legal immigrants are increasingly penalized as well. The difficulties involved in translating their legal status into higher wages and occupational status could engender feelings of exclusion among legal immigrants in employment settings. Schools are another setting where all children of immigrants are potentially treated as an undifferentiated mass, encouraging feelings of antagonism among those who, due to their legal status, have come to expect more. The only setting where legal status is negatively associated with perceptions of discrimination is in housing. Having valid identification seems to reduce exposure to unequal treatment from landlords and rental agencies. Interestingly, there is no evidence that documentation reduces perceptions of discrimination in interactions with the police.

Occupational characteristics reinforce prior findings; while working in non-niche occupations tend to expose immigrants to perceptions of discrimination, the opposite applies to working with other Latinos. While most elements of social support do not predict perceived discrimination in particular settings, regular church attendance is associated with increased perceptions of discrimination at work (0.30) and in public places (0.20). It is not uncommon for Church officials to advocate for immigrant rights, including warning migrants about employer abuses, particularly wage theft. It is possible that this kind of advocacy also contributes to immigrants’ awareness of their vulnerability in the U.S. labor market. Finally, indicators of transnationalism also suggest that temporary orientations might reduce perceptions of discrimination to varying degrees across settings. Results document that the effect is particularly prevalent in two contexts, renting and with the police. Temporary residents might not attempt to look for housing outside of immigrant neighborhoods, and might be less likely to have experienced police persecution. In a similar vein, those not planning to return to Latin American appear especially prone to report discrimination in public places.

Conclusions

Growth in the U.S. Latino population has renewed interest in the forces that shape immigrant incorporation. Latinos’ experiences with discrimination are central to debates about whether they will follow in the footsteps of earlier waves of European immigrants into upward mobility, or face enduring barriers to inclusion. In spite of the importance of the topic, our understanding of the forces that shape Latino perceptions of discrimination remains under-developed. This is especially the case in new destinations, which have attracted a growing share of the Latino population in recent decades and represent a markedly different context of reception than those of more traditional immigrant gateways. Accordingly, this paper assesses the prevalence and correlates of reported experiences with discrimination across social settings among Latino immigrants in Durham, NC, a new area of Latino destination in the Southeast. In addition to providing a benchmark measure that can be used to compare perceptions of discrimination across new and established areas of destinations we expand ongoing theoretical discussions surrounding the sources of discrimination by investigating the extent to which perceptions of unequal treatment vary by gender, legal status, family migration dynamics, and transnationalism.

Overall our results support social constructivists notions of ethnic processes that link experiences of discrimination to immigrants’ experiences and interactions with natives rather than cultural or primordialist traits. We show that factors traditionally considered as facilitators of incorporation from the assimilation perspective, such as higher levels of education, younger ages at arrival, English ability, and lengthier residence in the United States actually positively predict perceptions of discrimination. Likewise, greater occupational integration, in the form of working outside of traditional immigrant niches or predominantly Latino worksites, is also associated with greater perceived discrimination. The findings are consistent with the idea that ethnic experiences and awareness, including perceived discrimination, are very much part of the process of immigrant incorporation that might actually become more salient over time rather than reduced with adaptation.

More importantly, while generally overlooked in social constructivist notions of ethnicity, we show that perceptions of discrimination are highly structured by gender. Even though, on average, immigrant men and women report experiencing discrimination in a similar number of settings the specific social contexts producing perceptions of unequal treatment are highly gendered. While considerable research and policy attention has focused on interactions at work or with the police, they represent social settings that generally affect immigrant men more than immigrant women. The lower representation of women in those settings does not protect them from overall exposure to perceived discrimination, however. We show that women are more likely than men to report perceiving discrimination in schools and hospitals, which are the social settings where immigrant women are more likely to participate. Theoretically, these findings support intersectionality approaches that highlight the need to precisely investigate gender differences within minority groups in order to understand the production of disadvantage. From a practical standpoint, it suggests the need to move beyond the most obvious contexts of discrimination, namely the labor market and the legal system, and pay more attention to its most subtle expressions in public service institutions for understanding immigrant women’s position.

The study also highlights the importance of emerging dimensions of the immigrant experience for understanding perceptions of discrimination. Of special salience is documentation. As a marker of acceptance into the United States one could have expected that documented immigrants would report less discrimination since their social interactions should not be affected by legal status. Much of the anti-immigrant discourse in the United States frames the negative reactions of the dominant group as a reaction not against immigrants but against “law-breaking.” Contrary to this expectation, we found that reported discrimination is higher among those with legal status than those without it. The finding is again consistent with social constructivist approaches that relate discrimination to ethnic boundary formation and identity. For undocumented immigrants situations of unequal treatment are reasonably perceived as reactions against their lack of legal status. For legal immigrants, on the other hand, unequal treatment has no justification and unfavorable treatment is more likely to be interpreted on ethnic terms.

Similarly, aspects of social support and transnationalism affecting the Latino immigrant today also connect with perceptions of discrimination. Latino/a immigrants who hope to settle in the United States, and men who attend church regularly and migrated together with their wives, all report more perceived discrimination encounters than their peers who are less integrated on these dimensions. The finding again connects perceived discrimination to process of settlement rather than to cultural traits.

Overall, the study reinforces the growing recognition that perceptions of discrimination are a salient factor shaping the incorporation of contemporary Latin American immigrants, and that further research on the subject is needed. In the years ahead, a significant portion of the Latino immigrant population will face the task of incorporation in new destinations. Their experiences provide original grounds for a deeper exploration of how context and ethnicity shape immigrant outcomes, including perceptions of discrimination.

Footnotes

This research was supported by grant #NR 08052-03 from NINR/NIH (National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health).

We pilot tested the extent to which perceptions were better captured with an expanded scale rather than the simpler yes or no coding proposed in the original formulation (Kreiger 1990, 2005). However, consistent with the experience reported in Perez et al. (2008), we found the distribution in the disaggregated scale to be bi-modal, supporting the dichotomized measure.

The community members in our CBPR team posited that the particular experience of the Catholic Church in Durham contributed to these results. As Latino immigrants, especially families, began arriving to the area they concentrated in a single local church. This church at first attempted to integrate them into the larger community through bilingual mass, in Spanish and English. However, Anglo attendance was poor and the approach was soon abandoned in favor of separate masses. While the church was a strong advocate for newcomers, even helping to launch an independent grass-roots Latino advocacy organization, the ethnic divisions within the church were pronounced, potentially contributing to the sense of ethnic awareness among immigrant parishioners.

Contributor Information

Chenoa A. Flippen, University of Pennsylvania

Emilio A. Parrado, University of Pennsylvania

References

- Alba Richard. Ethnic Identity: The Transformation of White America. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Alba Richard, Nee Victor. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Assimilation. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Baker Phyllis. ‘It is the Only Way I Can Survive.’ Gender Paradox among Recent Mexicana Immigrants to Iowa. Sociological Perspectives. 2004;47:393–408. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Stevens Gillian. America’s Newcomers: Immigrant Incorporation and the Dynamics of Diversity. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brubaker Rogers, Loveman Mara, Stamatov Peter. Ethnicity as cognition. Theory and Society. 2004;33:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Chavez Leo R. The Latino Threat: Constructing Immigrants, Citizens, and the Nation. Stanford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Collins Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. New York, NY: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Finch Brian Karl, Kolody Bohdan, Vega William A. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-Origin adults in California. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2000;41(3):295–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen Chenoa. Laboring Underground: The Employment Patterns of Hispanic Immigrant Men in Durham, NC. Social Problems. 2012;59:21–42. doi: 10.1525/sp.2012.59.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen Chenoa. Intersectionality at work: Determinants of labor supply among Immigrant Hispanic women in Durham, NC. Gender and Society. 2013;20:1–31. doi: 10.1177/0891243213504032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flippen Chenoa, Parrado Emilio. Forging Hispanic Communities in New Destinations: A Case Study of Durham. Vol. 11. North Carolina: City & Community; 2012. pp. 1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza Tanya, Darity William., Jr Latino racial choices; the effects of skin colour and discrimination on Latinos’ and Latinas’ racial self-identifications. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2008;31:899–934. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon Milton M. Assimilation in American Life. New York: Oxford University Press; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan Jacquelin Maria. Migration Miracle: Faith, Hope, and Meaning on the Undocumented Journey. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Harnois Catherine E, Ifatunji Mosi. Gendered measures, gendered models: toward an intersectional analysis of interpersonal racial discrimination. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2011;34:1006–1028. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschman Charles. The Role of Religion in the Origins and Adaptation of Immigrant Groups in the United States. International Migration Review. 2004;38(3):1206–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Hondagneu-Sotelo Pierrette. Gendered Transitions: Mexican Experiences with Immigration. University of California Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington Samuel. The Hispanic Challenge. Foreign Policy. 2004 Mar-Apr;:30–46. [Google Scholar]

- Israel Barbara, Eng Eugenia, Schulz Amy, Parker Edith., editors. Methods in Community-based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez Tomás. Replenished Ethnicity: Mexican Americans, Immigration, and Identity. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Krieger Nancy, et al. Experiences of discrimination: Validity and reliability of a self-report measure for population health research on racism and health. Social Science and Medicine. 2005;61:1576–1596. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt Peggy, de la Dehesa Rafael. Transnational migration and the redefinition of the State: Variations and explanations. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2003;26:587–611. [Google Scholar]

- Mahler Sarah. American Dreaming. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marrow Helen. New immigrant destinations and the American colour line. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2009;32:1037–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Marrow Helen. New Destination Dreaming: Immigration, Race, and Legal Status in the Rural American South. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Bartley Katherine. The changing legal status distribution of immigrants: A caution. International Migration Review. 2006;39:469–484. [Google Scholar]

- Massey Douglas S, Sanchez Magaly. Brokered Boundaries: Creating Immigrant Identity in Anti-Immigrant Times. New York: Russell Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Menjivar Cecilia, Abrego Leisy. Legal violence: Immigration law and the lives of Central American immigrants. American Journal of Sociology. 2012;117:1380–1421. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel Joane. Constructing ethnicity: Creating and recreating ethnic identity and culture. Social Problems. 1994;41:152–176. [Google Scholar]

- National Research Council. Multiple Origins, Uncertain Destinies: Hispanics and the American Future. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olzak Susan. The Dynamics of Ethnic Competition and Conflict. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neil Kevin, Tienda Marta. A Tale of Two Counties: Perceptions and Attitudes toward Immigrants in New Destinations. International Migration Review. 2010;44(3):728–761. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2010.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ornelas India J, Eng Eugenia, Perreira Krista M. Perceived barriers to opportunity and their relation to substance use among Latino immigrant men. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2011;34:182–191. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9297-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oropesa RS, Jensen Leif. Dominican immigrants and discrimination in a new destination: The case of Reading, Pennsylvania. City and Community. 2010;9:274–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-6040.2010.01330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pager Devah, Shephard Hana. The sociology of discrimination: racial discrimination in employment, housing, credit and consumer markets. Annual Review of Sociology. 2008;34:181–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.33.040406.131740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Robert, Burgess Earnest. Introduction to the Science of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1921. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio, McQuiston Chris, Flippen Chenoa. Participatory Survey Research: Integrating Community Collaboration and Quantitative Methods for the Study of Gender and HIV Risks among Hispanic Migrants. Sociological Methods and Research. 2005;34:204–239. [Google Scholar]

- Parrado Emilio A, Morgan S. Philip. Intergenerational Fertility Patterns among Hispanic Women: New Evidence of Immigrant Assimilation. Demography. 2008;45(3):651–671. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Debra Jay, Fortuna Lisa, Alegría Margarita. Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among Latinos Journal of Community Psychology. 2008;36:421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro. The rise of ethnicity: Determinants of ethnic perceptions among Cuban exiles in Miami. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:383–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Bach R. Latin Journey: Cuban and Mexican Immigrants in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Rumbaut Ruben. Immigrant America: A Portrait. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; [1996] 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, Guarnizo Luis E., Landolt Patricia. The study of transnationalism: Pitfalls and promise of an emergent research field. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1999;22:217–237. [Google Scholar]

- Portes Alejandro, MacLeod Dag. What shall I call myself? Hispanic identity formation in the second generation. Ethnic and Racial Studies. 1996;19:523–547. [Google Scholar]

- Schnittker Jason, McLeod Jane D. The social psychology of health disparities. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:75–103. [Google Scholar]

- Smith James. Assimilation Across the Latino Generations. American Economic Review. 2003;93(2):315–319. [Google Scholar]

- Telles Edward E, Ortiz Vilma. Generations of Exclusion: Mexican Americans, Assimilation, and Race. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Warner William Lyod, Srole Leo. The Social Systems of American Ethnic Groups. Yale University Press; 1945. [Google Scholar]

- Waters John, Biernacki Patrick. Targeted sampling: Options for the study of hidden populations. Social Problems. 1989;36:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Waters Mary, Jiménez Tomás R. Assessing immigrant assimilation: New empirical and theoretical challenges. Annual Review of Sociology. 2005;31:105–125. [Google Scholar]

- White Michael, Glick Jennifer. Achieving Anew: How New Immigrants Do in American Schools, Jobs, and Neighborhoods. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer Andreas. Ethnic Boundary Making: Institutions, Power, Networks. London: Oxford University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Yinger Milton J. Ethnicity. Annual Review of Sociology. 1985;11:151–180. [Google Scholar]

- Yinger Milton J. Ethnicity. Source of Strength? Source of Conflict? Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]