Abstract

Gene expression profiling studies on breast cancer have generated catalogs of differentially expressed genes. However, many of these genes have not been investigated for their expression at the protein level. It is possible to systematically evaluate such genes in a high-throughput fashion for their overexpression at the protein level using breast cancer tissue microarrays. Our strategy involved integration of information from publicly available repositories of gene expression to prepare a list of genes upregulated at the mRNA level in breast cancer followed by curation of the published literature to identify those genes that were not tested for overexpression at the protein level. We identified Kinesin Associated Protein 3 (KIFAP3) as one such molecule for further validation at the protein level. Immunohistochemical labeling of KIFAP3 using breast cancer tissue microarrays revealed overexpression of KIFAP3 protein in 84% (240/285) of breast cancers indicating the utility of our integrated approach of combining computational analysis with experimental biology.

Keywords: Breast neoplasms, KAP3, SMAP, SmgGDS associated protein, Immunohistochemistry

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer death among women [1,2]. In the last decade, the majority of studies that have been carried out to understand breast tumors have focused on molecular alterations that accompany the process of oncogenesis. Aberrant levels of gene and protein expression are important events in cancer initiation and progression. A number of gene expression profiling studies have identified genes that are up or downregulated at the mRNA level in breast cancer [3–5]. Some of these genes have been reported to be differentially expressed across multiple studies involving large sample sets. However, these observations become significant only when they are supported by systematic validation at the protein level. Thus, we carried out a bioinformatics analysis of publicly available gene expression datasets and the published literature to identify genes that are reported to be overexpressed at the transcript level in breast cancers but have not yet been tested for their protein expression. Among the shortlisted molecules, KIFAP3 was chosen for validation at the protein level by immunohistochemical labeling of breast cancer Tissue Microarrays (TMAs).

Kinesins are a family of microtubule dependent motor proteins which transport molecules by using the chemical energy from breakdown of ATP enabled by their ATPase activity. This group of proteins plays a crucial role in transporting various cargos like organelles, nucleic acids and proteins. To carry out their role of transporting cargo efficiently, kinesins rely on a number of additional proteins [6,7]. Fourteen Kinesin families are known till date along with multiple accessory proteins [8]. Kinesin-2 is a heterotrimer made up of two motor proteins, Kinesin family member 3A (KIF3A) and Kinesin family member 3B (KIF3B). KIFAP3 is the third non-motor protein associated with the tail domain of KIF3A/KIF3B motor proteins through which these motor proteins are linked to cargo. Kinesin-2 has been shown to take part in organelle transport [9], lipid raft protein transport, mitosis related function [10,11] and vesicle mediated transport [12].

KIFAP3 gene is located on chromosome 1q24 locus and codes for a 90 kDa protein which has 3 armadillo repeats. It is also referred as SmgGDS-associated Protein (SMAP), since it interacts with SmgGDP dissociation stimulator (SmgGDS). SmgGDS is a regulatory protein that is involved in GTP/GDP exchange in small G proteins such as Rho, member of the Rap1 family [13,14] and Ki-Ras. It also modulates lipid mediated post-translational modification of small G-proteins [15]. SmgGDS also negatively regulates the interaction between lipid modified small G-proteins and plasma membrane [16]. KIFAP3 was identified as a SmgGDS interacting protein in a cell free system [17]. KIFAP3 was shown to be localized to the nucleus, the cytoplasm and the Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER) [17,18].

KIFAP3 interacts with several other proteins like Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) [19], c-Src [17], Human Chromosome Associated Polypeptide (HCAP) [18] and other proteins through its armadillo repeat domains. It has been shown that phosphorylation by Src results in reduced affinity of KIFAP3 to SmgGDS. The kinesin-2 machinery is involved in retrograde transport of COPI (coat protein complex I) coated vesicles from the Golgi complex to the ER and downregulation of KIFAP3 results in disruption of this function [20].

In the current study, we have performed immunohistochemical validation of KIFAP3 protein in a large cohort of breast cancer patients. We found overexpression of KIFAP3 in 84% of the cases. Our results suggest that KIFAP3 can be a good candidate protein that can be studied further for its specific role in breast neoplasms.

Materials and Methods

Immunohistochemical labeling

Immunohistochemical labeling for KIFAP3 was carried out on breast cancer tissue microarrays (n=44) that were prepared by JCR (Universidad de La Frontera, Temuco, Chile). The rabbit polyclonal antibody against KIFAP3 was purchased from the Human Protein Atlas (catalog # HPA023738). The optimum dilution for the anti-KIFAP3 antibody was found to be 1:15. The immunohistochemical staining procedure was carried out as previously described by Kashyap et al. [21]. Briefly, the tissue microarrays were deparaffinized and antigen retrieval was carried out using HIER (Heat-Induced Epitope Retrieval) by incubating them for 20 minutes in antigen retrieval buffer (0.01 M Trisodium citrate buffer, pH 6). The quenching of endogenous peroxidases was done by using blocking solution (ready- to- use from Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). This was followed by three washes with the wash buffer (PBS, pH 7). The sections were incubated after addition of primary antibody overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. After removal of primary antibody followed by washing, the slides were incubated with appropriate horseradish peroxidase conjugated secondary antibody (Vector labs, Burlingame, CA) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Immunoperoxidase staining was developed for 3 minutes using DAB chromogen (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) followed by counterstaining using hematoxylin (Nice Chemicals, India). Only the antibody diluent was used instead of primary antibody as the negative control. The microscopy was done using the LEITZ DMRB model of Leica (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). All the images were captured at a magnification of 200×. The immunohistochemically labeled sections were scored by an experienced pathologist (JM), and the staining intensity was given the scores of 0 for negative, 1+ for mild, 2+ for moderate and 3+ for strong. The distribution of staining of cancer cells was scored as 0 (less than 5% of cells staining), 1+ (5%–30% of cells staining), 2+ (31%–60% of cells staining) or 3+ (greater than 60% of cells staining). The intensities of staining were compared between carcinoma cells and that of normal breast tissue.

Public availability and accessibility of immunohistochemistry data

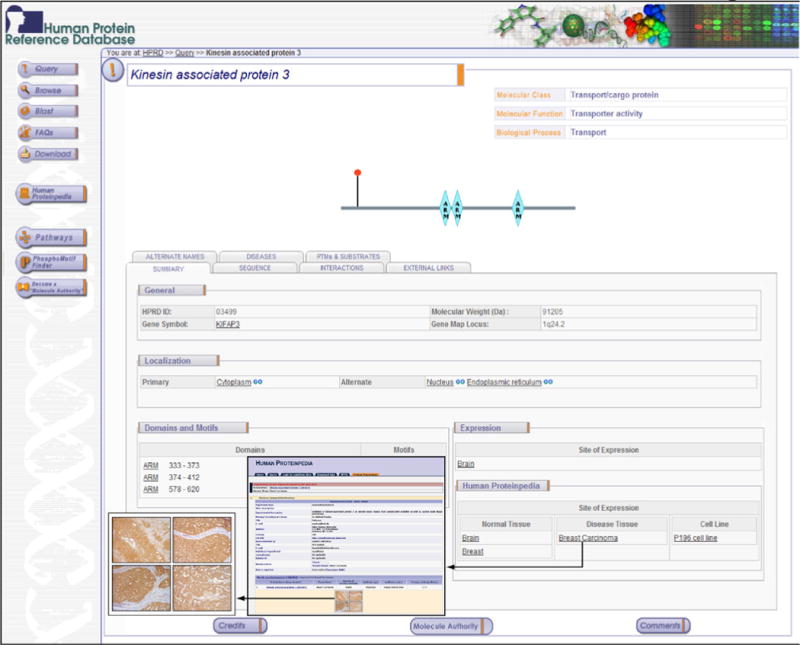

To make our findings accessible to other researchers, we have submitted the data from immunohistochemical labeling of KIFAP3 to Human Proteinpedia (HUPA; http://www.humanproteinpedia.org) [22]. The expression of KIFAP3 in normal breast epithelium (http://www.humanproteinpedia.org/Experimental_details?exp_id=TE-142795) and in breast cancer (http://www.humanproteinpedia.org/Experimental_details?can_id=105418) can be visualized in separate pages. Figure 1 shows a screenshot of Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD; http://www.hprd.org) [23] page for KIFAP3 protein and also of HUPA resource displaying KIFAP3 expression in normal breast tissue and breast carcinoma.

Figure 1. Human Protein Reference Database (HPRD) and Human Proteinpedia annotations for KIFAP3.

This figure is a screenshot of the HPRD molecule page for KIFAP3 protein that provides information about the protein, architecture, post-translational modifications, subcellular localization and tissue expression of the molecule. The immunohistochemical data from this study as displayed in Human Proteinpedia is shown in the inset

Results and Discussion

Selection of KIFAP3 as a candidate marker for validation

Gene expression data from publicly available resources such as Gene Expression Atlas (GEA) [24] and Oncomine [25] was searched to generate a list of genes reported to be overexpressed in breast cancer. The published literature was mined to find out which of these differentially expressed genes were previously studied with respect to protein level expression in breast cancer. Among these molecules, KIFAP3 was chosen since a) its mRNA expression profile in Oncomine and GEA indicated that it is overexpressed across several breast tumors and cell lines; b) it was shown to be >3 fold upregulated in breast tumors at mRNA level in a high-throughput study by Grigoriadis et al. [26], and, c) its expression was has not yet been reported at the protein level in breast cancer.

KIFAP3 is an interesting molecule to test because it has been shown to be associated with proteins that are known to mediate carcinogenesis. It has been shown that the KIFAP3-APC interaction is important in cell migration, a crucial event in cancer progression [19,27]. APC is a tumor suppressor protein which plays an essential role in cell cycle control [28]. Lukong and Richard [29], have shown that KIFAP3 is phosphorylated by breast tumor kinase (BRK or PTK6) in the BT20 breast cancer cell line. They also observed that BRK drastically alters the localization of KIFAP3 and that KIFAP3 is required for BRK-induced cell migration. They hypothesized that KIFAP3 might be a key effector in the BRK signaling pathway in breast carcinomas. BRK is known to be overexpressed in more than 60% of breast tumors [29–34] and is a component of the ErbB-Brk-Rac-p38 MAPK pathway and is a critical mediator of breast cancer cell migration [34,35]. The interaction of KIFAP3 with BRK, a protein with an important role in breast tumor progression, makes it an attractive candidate for validation of its overexpression in breast carcinomas.

KIFAP3 was specifically selected for validation taking into consideration (a) the availability of an antibody in the Human Protein Atlas (HPA) (http://www.proteinatlas.org/) [36] (b) its role in mitosis and cell cycle regulation and (c) its interactions with the proteins APC and BRK that play a significant role in cancer initiation and progression.

Expression of KIFAP3 in breast tumors

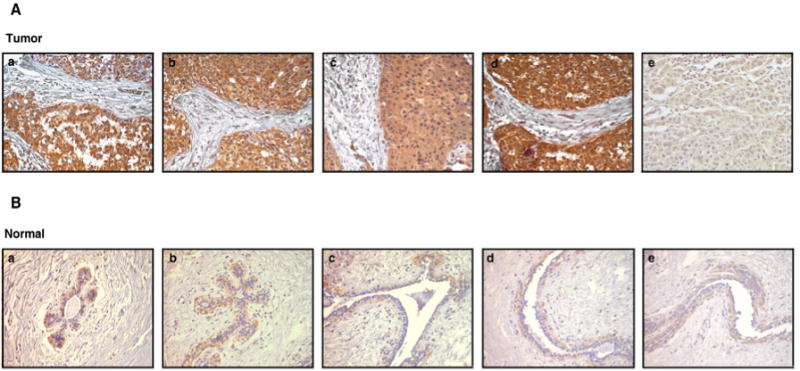

Immunohistochemical labeling was performed on tissue microarrays using a commercially available antibody against KIFAP3. The immunogen was a 91 amino acid recombinant protein fragment which was used to generate the polyclonal antibody in rabbit (http://www.proteinatlas.org/ENSG00000075945/antibody). The Immunohistochemical staining pattern of KIFAP3 in a few representative sections of normal breast tissue and breast cancer tissues is shown in Figure 2. We observed expression of KIFAP3 in almost all breast ductal carcinoma tissues that were tested and majority of tumors were strongly stained for KIFAP3. KIFAP3 expression was predominantly found to be localized in the cytoplasm of tumor cells (Figure 2A panel a–d). A breast cancer section that does not stain positive for KIFAP3 is shown in panel e in Figure 2A.

Figure 2. The pattern of expression of KIFAP3 protein breast cancers and normal breast tissue sections.

Tissue sections from TMAs stained with anti-KIFAP3 antibody. (A) This panel of five tissue sections represents breast cancer cases. Tumor sections a-d show significant overexpression of the KIFAP3 protein. Tumor section e represents a case that does not show KIFAP3 overexpression (B) This panel represents five normal breast tissue sections showing a weak expression of KIFAP3. All images were acquired at 200× magnification.

In normal breast tissue, there was weak to moderate staining of epithelial cells for KIFAP3 and its expression was localized to the cytoplasm (Figure 2B). The staining pattern of KIFAP3 protein in tumor and normal tissues is summarized in Table 1. As shown in the table, 84% (240/285) of the tumors showed overexpression of KIFAP3. The expression of KIFAP3 in all 14 controls tested showed a weak cytoplasmic staining. Out of the 285 cases tested, 227 cases showed strong positive staining in carcinoma cells alone, four cases showed positive staining in tumor as well as the stromal components and nine cases showed overexpression only in the stroma but not in the tumor cells. Finak et al. [37] have reported the overexpression of KIFAP3 in breast cancer stroma as compared to normal stroma in a high-throughput gene expression profiling study. Our observation of stromal expression of KIFAP3 in breast tumors is in agreement with the above findings.

Table 1.

Summary of immunohistochemical labeling for KIFAP3 in breast carcinoma tissues.

| Number of cases | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Number of cases tested | 285 |

| 2. | Number of positive cases | 240 |

| 3. | Number of cases with positive staining of carcinoma cells alone | 227 |

| 4. | Number of cases with positive staining of stroma alone | 9 |

| 5. | Number of cases with positive staining of both carcinoma and stromal component | 4 |

Conclusions

Gene expression databases provide enormous information about differentially regulated genes. Integration of this data coupled to literature mining followed by systematic validation led us to find novel potential biomarkers in breast cancer. This study shows how a bioinformatics approach to find novel candidate biomarkers for cancers can be an effective means to find an interesting molecule for validation in a relatively short time. Using this approach, we found that KIFAP3 gene, which was reported to be upregulated at mRNA level in breast tumors, is also overexpressed at the protein level. We believe that this approach will assist in identification of additional potential candidate markers in other cancers as well. Our study should enable other functional studies to unravel the exact role of KIFAP3 in breast cancer initiation, progression and invasion.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Department of Biotechnology (DBT), Government of India for research support to the Institute of Bioinformatics, Bangalore. This study was supported in part by an NIH roadmap grant for Technology Centers of Networks and Pathways (U54RR020839). Deepthi Telikicherla is a recipient of a Senior Research Fellowship from the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR), New Delhi, Government of India. Harsh Pawar is a recipient of Senior Research Fellowship from the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Government of India. We would like to thank Dr. S. K. Shankar and Dr. Anita Mahadevan of National Institute of Mental Health and Neurological Sciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore for providing access to the imaging facility.

Abbreviations

- KIFAP3

Kinesin Associated Protein 3

- KIF3A

Kinesin Family Member 3A

- KIF3B

Kinesin Family Member 3B

- COPI

Coat Protein Complex I

- SmgGDS

Small G Protein GDP Dissociation Stimulator

- APC

Adenomatous Polyposis Coli

- Src-v-src

Sarcoma (Schmidt-Ruppin A-2) Viral Oncogene Homolog (avian)

- HCAP

Human Chromosome Associated Polypeptide

- TMA

Tissue Microarrays

References

- 1.Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, et al. Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int J Cancer. 2010;127:2893–2917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, Ferlay J, Ward E, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedenfalk I, Duggan D, Chen Y, Radmacher M, Bittner M, et al. Gene-expression profiles in hereditary breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102223440801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van de Vijver MJ, He YD, van’t Veer LJ, Dai H, Hart AA, et al. A gene-expression signature as a predictor of survival in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1999–2009. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, et al. Gene-expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirokawa N, Noda Y. Intracellular transport and kinesin superfamily proteins, KIFs: structure, function, and dynamics. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:1089–1118. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00023.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daire V, Pous C. Kinesins and protein kinases: key players in the regulation of microtubule dynamics and organization. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2011;510:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2011.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wordeman L. How kinesin motor proteins drive mitotic spindle function: Lessons from molecular assays. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2010;21:260–268. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruno L, Salierno M, Wetzler DE, Desposito MA, Levi V. Mechanical properties of organelles driven by microtubule-dependent molecular motors in living cells. PLoS One. 2011;6:e18332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haraguchi K, Hayashi T, Jimbo T, Yamamoto T, Akiyama T. Role of the kinesin-2 family protein, KIF3, during mitosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:4094–4099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507028200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller MS, Esparza JM, Lippa AM, Lux FG, 3rd, Cole DG, et al. Mutant kinesin-2 motor subunits increase chromosome loss. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:3810–3820. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-05-0404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park JJ, Cawley NX, Loh YP. Carboxypeptidase E cytoplasmic tail-driven vesicle transport is key for activity-dependent secretion of peptide hormones. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:989–1005. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamamoto T, Kaibuchi K, Mizuno T, Hiroyoshi M, Shirataki H, et al. Purification and characterization from bovine brain cytosol of proteins that regulate the GDP/GTP exchange reaction of smg p21s, ras p21-like GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:16626–16634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Isomura M, Kaibuchi K, Yamamoto T, Kawamura S, Katayama M, et al. Partial purification and characterization of GDP dissociation stimulator (GDS) for the rho proteins from bovine brain cytosol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1990;169:652–659. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(90)90380-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hiroyoshi M, Kaibuchi K, Kawamura S, Hata Y, Takai Y. Role of the C-terminal region of smg p21, a ras p21-like small GTP-binding protein, in membrane and smg p21 GDP/GTP exchange protein interactions. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2962–2969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim YS, Kikuchi A, Takai Y. Effect of chlorpromazine on the smg GDS action. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;182:1446–1453. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)91896-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu K, Kawabe H, Minami S, Honda T, Takaishi K, et al. SMAP, an Smg GDS-associating protein having arm repeats and phosphorylated by Src tyrosine kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27013–27017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.27013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shimizu K, Shirataki H, Honda T, Minami S, Takai Y. Complex formation of SMAP/KAP3, a KIF3A/B ATPase motor-associated protein, with a human chromosome-associated polypeptide. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6591–6594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.12.6591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimbo T, Kawasaki Y, Koyama R, Sato R, Takada S, et al. Identification of a link between the tumour suppressor APC and the kinesin superfamily. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:323–327. doi: 10.1038/ncb779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stauber T, Simpson JC, Pepperkok R, Vernos I. A role for kinesin-2 in COPI-dependent recycling between the ER and the Golgi complex. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2245–2251. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kashyap MK, Marimuthu A, Kishore CJ, Peri S, Keerthikumar S, et al. Genomewide mRNA profiling of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma for identification of cancer biomarkers. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:36–46. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.1.7090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mathivanan S, Ahmed M, Ahn NG, Alexandre H, Amanchy R, et al. Human Proteinpedia enables sharing of human protein data. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:164–167. doi: 10.1038/nbt0208-164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peri S, Navarro JD, Kristiansen TZ, Amanchy R, Surendranath V, et al. Human protein reference database as a discovery resource for proteomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D497–D501. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kapushesky M, Emam I, Holloway E, Kurnosov P, Zorin A, et al. Gene expression atlas at the European bioinformatics institute. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:D690–698. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, Deshpande N, Varambally R, et al. ONCOMINE: A Cancer Microarray Database and Integrated Data-Mining Platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6:1–6. doi: 10.1016/s1476-5586(04)80047-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grigoriadis A, Mackay A, Reis-Filho JS, Steele D, Iseli C, et al. Establishment of the epithelial-specific transcriptome of normal and malignant human breast cells based on MPSS and array expression data. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8:R56. doi: 10.1186/bcr1604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teng J, Rai T, Tanaka Y, Takei Y, Nakata T, et al. The KIF3 motor transports N-cadherin and organizes the developing neuroepithelium. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:474–482. doi: 10.1038/ncb1249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura Y. The adenomatous polyposis coli gene and human cancers. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1995;121:529–534. doi: 10.1007/BF01197765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lukong KE, Richard S. Breast tumor kinase BRK requires kinesin-2 subunit KAP3A in modulation of cell migration. Cell Signal. 2008;20:432–442. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Born M, Quintanilla-Fend L, Braselmann H, Reich U, Richter M, et al. Simultaneous over-expression of the Her2/neu and PTK6 tyrosine kinases in archival invasive ductal breast carcinomas. J Pathol. 2005;205:592–596. doi: 10.1002/path.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aubele M, Auer G, Walch AK, Munro A, Atkinson MJ, et al. PTK (protein tyrosine kinase)-6 and HER2 and 4, but not HER1 and 3 predict long-term survival in breast carcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:801–807. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barker KT, Jackson LE, Crompton MR. BRK tyrosine kinase expression in a high proportion of human breast carcinomas. Oncogene. 1997;15:799–805. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aubele M, Vidojkovic S, Braselmann H, Ritterswurden D, Auer G, et al. Overexpression of PTK6 (breast tumor kinase) protein–a prognostic factor for long-term breast cancer survival–is not due to gene amplification. Virchows Arch. 2009;455:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s00428-009-0809-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ostrander JH, Daniel AR, Lofgren K, Kleer CG, Lange CA. Breast tumor kinase (protein tyrosine kinase 6) regulates heregulin-induced activation of ERK5 and p38 MAP kinases in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:4199–4209. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ostrander JH, Daniel AR, Lange CA. Brk/PTK6 signaling in normal and cancer cell models. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10:662–669. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhlen M, Bjorling E, Agaton C, Szigyarto CA, Amini B, et al. A human protein atlas for normal and cancer tissues based on antibody proteomics. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2005;4:1920–1932. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500279-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Finak G, Bertos N, Pepin F, Sadekova S, Souleimanova M, et al. Stromal gene expression predicts clinical outcome in breast cancer. Nat Med. 2008;14:518–527. doi: 10.1038/nm1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]