Abstract

Policing necessitates exposure to traumatic, violent and horrific events, which can lead to an increased risk for developing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The purpose of this study was to determine whether the frequency, recency, and type of police-specific traumatic events were associated with PTSD symptoms. Participants were 359 police officers from the Buffalo Cardio-Metabolic Occupational Police Stress (BCOPS) Study (2004–2009). Traumatic police events were measured using the Police Incident Survey (PIS); PTSD was measured using the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C). Associations between PIS and PTSD symptoms were evaluated using ANCOVA. Contrast statements were used to test for linear trends. Increased frequency of specific types of events were associated with an increase in the PCL-C score in women, particularly women with no history of prior trauma and those who reported having a high workload (p < 0.05). More recent exposure to seeing severely assaulted victims was associated with higher PCL-C scores in men (p < 0.02). In summary, the frequency of several traumatic events was associated with higher PTSD scores in women, while the recency of seeing victims of assault was associated with higher PTSD scores in men. These results may be helpful in developing intervention strategies to reduce the psychological effects following exposure and these strategies may be different for men and women.

Keywords: Police officers, traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorder

More than half of U.S. adults are exposed to a severe stressor at some point during the course of their life (Sledjeski, Speisman, & Dierker, 2008). This number is much higher for occupational groups such as police officers and firefighters (Kaufmann, Rutkow, Spira, & Mojtabai, 2012). Patterson (2001) reported that police officers experience, on average, over three traumatic events for every six months of service. Police-specific traumatic events may include violent events such as armed conflicts, and more sad and depressing incidents such as abusive violence, providing assistance to victims of severe traffic accidents, and handling dead bodies.

Numerous health consequences have been associated with exposure to traumatic events in police officers and other emergency responders. Neylan and colleagues (2002) found increased critical incident exposure to be associated with poorer sleep quality. North et al. (2002) found traumatic events to be associated with a high prevalence of alcohol abuse and dependence among responders to the Oklahoma City bombing. Others have reported a high prevalence of mental health problems among 9/11 rescue operators (Perrin et al., 2007; Stellman et al., 2008), and a high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depression among police officers and firefighters who responded to Hurricane Katrina (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006).

Symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the event, avoidance of situations that bring back memories of the event, and hyperarousal including difficulty sleeping and trouble concentrating (National Center for PTSD, 2013). While these symptoms may be common during the first few weeks after a traumatic event, lingering symptoms of a month or more may indicate PTSD. Previous studies have identified several risk factors for PTSD. The severity of the traumatic event is associated with increased risk of PTSD development (Carlier, Lamberts, & Gersons, 1997). Previous assaultive trauma was associated with a higher risk of PTSD from subsequent trauma than previous trauma not involving assaultive violence (Breslau, Chilcoat, Kessler & Davis, 1999). Women are more likely than men to develop PTSD after a traumatic event (Gavranidou & Rosner, 2003; Breslau et al., 1999). Specifically in police officers, Hodgins, Creamer & Bell (2001) found that personality style, sex, and trait dissociation to be associated with PTSD in early career officers. Kaufmann et al. (2013) found a significant association between traumatic event exposure and incident psychological distress among early career police officers who may be experiencing the events for the first time.

PTSD may impact an individual’s physical and psychological health. PTSD symptoms have been significantly associated with increased general health symptoms and conditions, poorer physical health-related quality of life, greater frequency and severity of pain, and cardio-respiratory and gastrointestinal complaints (Pacella, Hruska, & Delahanty, 2013). Higher PTSD symptomatology has been associated with higher waking cortisol measures in police officers (Austin-Ketch et al., 2012). Researchers have found a significant and independent association between ischemia triggered during a standard treadmill test in veterans with clinical PTSD compared to those without PTSD (Turner, Neylan, Schiller, Li, & Cohen, 2013; Lukaschek et al., 2013). Patients with diagnosed PTSD may also have comorbid psychological disorders including anxiety and depression, and substance abuse and addictions, (Javidi & Yadollahie, 2012). Stuart (2008) reported an increased risk of suicide among those with PTSD.

In the current study, the association of frequency, recency, and the type of police-specific traumatic events with symptoms of PTSD are examined among police officers participating in the Buffalo Cardio-Metabolic Occupational Police Stress (BCOPS) Study. The role of male gender, military service experience, and low workload in accounting for a potentially protective effect of occurrence, frequency, and recency of each specific type of traumatic event on PTSD symptomatology is also examined.

METHODS

Study Participants

Participants were police officers from the BCOPS Study. The objective of the BCOPS Study was to cross-sectionally assess the association between psychological stress and subclinical cardiovascular disease among police officers examined between 2004 and 2009. Data were collected at the Center for Health Research, School of Public Health and Health Professions, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY. No specific inclusion criteria were used for the study, other than the participant would be a sworn police officer and willing to participate in the study. Women officers pregnant at the time of examination were excluded (n=2). All 710 active duty police officers from the Buffalo, NY Police Department were invited to participate with 431 officers completing the clinical examination (60.7%). Of these officers, 72 were removed from analyses due to missing data leaving a final sample of 359 officers (260 men, 99 women). All participants provided informed consent and all phases, testing, and reports of the study were approved by the State University of New York at Buffalo Internal Review Board and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Human Subjects Review Board.

Police Incident Survey

Police-specific traumatic events were measured using the 9-item Police Incident Survey developed by Violanti and Gherke (2004). Participants were asked to indicate whether they had experienced each of eight events in the past year (i.e. event occurrence), and if ‘yes’ indicate the number of occurrences (i.e. event frequency) and the time since they last experienced the event (in months) (i.e. event recency). The eight events included witnessing the shooting of another police officer, being involved in a shooting incident, seeing abused children, seeing victims of a serious traffic accident, seeing someone die, seeing dead bodies, seeing severely assaulted victims and seeing victims of a homicide. One open-ended question asked about other events not listed; information about occurrence and frequency but not event type were used in the analysis. Two summary measures were created: 1) total traumatic incident occurrence – the number of events officers reported experiencing in the past year from 0–9, and 2) most recent occurrence – the last time any event occurred from 0–12 months ago.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C)

Symptoms of PTSD were measured using the 17-item PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C). The PCL-C was developed by Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska & Keane (1993) at the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for PTSD. The 17 questions correspond to 17 DSM-IV symptoms of PTSD and participants rated the severity of each symptom in the past month on a 5-point scale from ‘1-Not at all’ to ‘5-Extremely’. The PCL-C has three sub-scales, re-experiencing, avoidance and hyperarousal, which correspond to the 3 DSM-IV symptom clusters. According to Weathers, et al., there is no standard cut point for the checklist. For descriptive purposes, we reported prevalence of PTSD using two approaches: 1) established cut points: 25 – Screening level for PTSD in the VA Primary Care Clinic, 33 – Diagnostic level for PTSD in the VA Primary Care Clinic, and 44 – Screening level for civilian motor vehicle accident victims (National Center for PTSD, 2011); and 2) clustering: partial PTSD – having significant symptoms in two of three clusters, and full PTSD – having significant symptoms in all three clusters (Maia et al. 2007). Due to the low prevalence of PTSD found with both approaches, the mean PCL-C score was used for analyses.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the study population. Gender-specific tertiles were created for each police stress variable. Prevalence estimates and means (standard deviations, SD) were calculated for the traumatic police events and PCL-C scores. Analysis of variance and covariance were used to estimate the unadjusted and multivariable adjusted mean PCL-C score across categories of traumatic event frequency and recency. Tests for trend were obtained from linear contrast. The multivariable models were adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and educational level. The covariates to adjust for were chosen based on their association with traumatic events and the PCL-C scores and evidence in the literature. The results were stratified by gender in order to compare associations between male and female officers. In addition to gender, the models were stratified separately by military experience, workload (low to moderate vs. high level of activity and crime in the officer’s precinct area), and trauma exposure prior to policing as the tests for interaction with traumatic events were significant (p < 0.15). All analyses were conducted using the SAS software, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of the study population are found in Table 1. Over one-quarter of participants were women (27.6%). Participants were about 41 years old and the majority was white. Women had slightly fewer years of service (13.1 years vs. 14.5 years), were more likely to be a patrol officer (81.6% vs. 74.1%), work the day shift (67.0% vs. 26.7%), and have higher levels of peritrauma (71.2% vs. 64.3%) compared to men. A higher percentage of men had prior military experience (26.1% vs. 11.2%), reported having a high workload (68.5% vs. 50.5%) and prior trauma exposure (50.0% vs. 40.0%) than women officers.

Table 1.

Demographic and lifestyle characteristics by sex.

| Characteristic or Measure | Men N = 260

|

Women N = 99

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SD) or % | N | Mean (SD)or % | |

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean | 260 | 40.7 (6.7) | 99 | 40.6 (6.0) |

| < 40 | 115 | 44.2 | 41 | 41.4 |

| 40 – 49 | 114 | 43.8 | 50 | 50.5 |

| 50 + | 31 | 11.9 | 8 | 8.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 195 | 78.3 | 71 | 72.5 |

| African American | 50 | 20.1 | 27 | 27.6 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 1.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Education | ||||

| High School or less | 34 | 13.5 | 4 | 4.1 |

| College < 4 years | 133 | 52.8 | 63 | 64.3 |

| College 4 + years | 85 | 33.7 | 31 | 31.6 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Single | 24 | 9.5 | 24 | 24.5 |

| Married | 193 | 76.6 | 56 | 57.1 |

| Divorced | 35 | 13.9 | 18 | 18.4 |

| Police Service, years | ||||

| Mean | 253 | 14.5 (6.6) | 98 | 13.1 (6.3) |

| 0 – 9 | 66 | 26.1 | 37 | 37.8 |

| 10 – 14 | 62 | 24.5 | 21 | 21.4 |

| 15 – 19 | 61 | 24.1 | 21 | 21.4 |

| 20 + | 64 | 25.3 | 19 | 19.4 |

| Rank | ||||

| Patrol Officer | 186 | 74.1 | 80 | 81.6 |

| Sergeant/Lieutenant/Captain | 35 | 13.9 | 10 | 10.2 |

| Detective/Executive/Other | 30 | 12.0 | 8 | 8.2 |

| Prior Military Experience | 66 | 26.1 | 11 | 11.2 |

| Shiftwork | ||||

| Day | 67 | 26.7 | 65 | 67.0 |

| Afternoon | 110 | 43.8 | 18 | 18.6 |

| Midnight | 74 | 29.5 | 14 | 14.4 |

| Workload | ||||

| Low or Moderate | 79 | 31.5 | 47 | 49.5 |

| High | 172 | 68.5 | 48 | 50.5 |

| Alcohol Intake, drinks/week | 251 | 5.0 (7.4) | 96 | 3.6 (6.1) |

| Smoking Status | ||||

| Current | 36 | 14.2 | 27 | 28.4 |

| Former | 46 | 18.2 | 28 | 29.5 |

| Never | 171 | 67.6 | 40 | 42.1 |

| Physical Activity Index | 251 | 21.1 (18.0) | 97 | 22.3 (18.2) |

| Prior Trauma | ||||

| No | 104 | 50.0 | 45 | 60.0 |

| Yes | 104 | 50.0 | 30 | 40.0 |

| Peritraumatic Dissociative Experience | ||||

| < 10 – No symptoms | 74 | 35.8 | 21 | 28.8 |

| ≥ 10 – Few symptoms or greater | 113 | 64.3 | 52 | 71.2 |

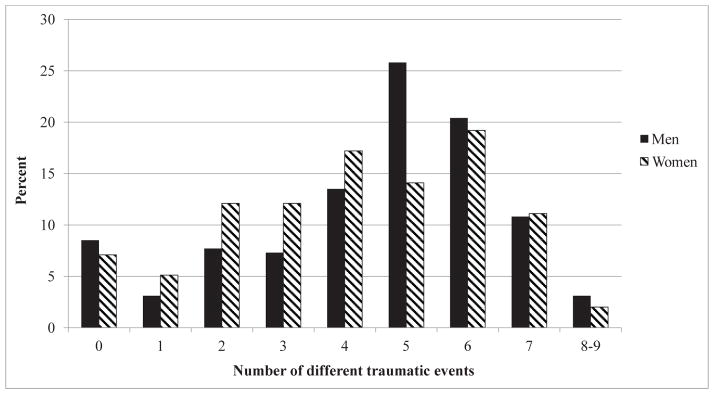

Approximately 80% of the officers reported seeing dead bodies and severely assaulted victims in the past year (Table 2). This was followed by seeing victims of homicide, abused children and victims of serious traffic accidents. Individual event occurrences were generally similar between men and women; except men were more likely to see homicide victims than women (71.2% vs. 58.6%). Frequencies of the specific events were also similar between men and women. Male officers reported seeing severely assaulted victims on average 14 times in the past year while female officers reported 10 times. Women reported seeing more abused children than men (8.8 times vs. 6.9 times), and men reported seeing more homicide victims than women (5.5 times vs. 3.7 times). The most recent traumatic event for men and women was seeing severely assaulted victims (1.6 months ago for men, 1.4 for women). Of the nine types of events, officers reported witnessing a total of 4.4 in the past year with 60.1% of men and 46.4% of women witnessing five or more different types of events (Figure 1). On average, the majority of male (82.6%) and female officers (76.4%) reported experiencing a traumatic event in the past month (data not shown).

Table 2.

Traumatic event occurrence, frequency and recency by sex.

| Traumatic Event | Occurred In Past Year Mean (SD)

|

Frequency In Past Year Mean (SD)

|

Months Since Last Occurrence Mean (SD)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men N=260 | Women N=99 | Men N=260 | Women N=99 | Men N=260 | Women N=99 | |

| Shooting of another officer | 27 (10.4) | 3 (3.0) | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.0) | 5.0 (3.7) | 4.7 (4.0) |

| Involvement in a shooting | 22 (8.6) | 7 (7.1) | 6.0 (6.5) | 6.1 (7.2) | 3.5 (3.4) | 2.0 (2.0) |

| Seeing abused children | 166 (63.9) | 64 (64.7) | 6.9 (10.7) | 8.8 (13.1) | 2.8 (2.6) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| Seeing victims of a serious traffic accident | 167 (64.2) | 62 (62.6) | 5.5 (5.5) | 4.8 (4.7) | 2.8 (2.5) | 3.0 (2.8) |

| Seeing someone die in front of you | 94 (36.2) | 23 (23.5) | 2.3 (2.4) | 1.5 (0.7) | 4.5 (3.3) | 5.2 (3.1) |

| Seeing dead bodies | 217 (83.5) | 80 (80.8) | 7.1 (7.4) | 7.4 (9.8) | 2.4 (2.2) | 2.7 (2.9) |

| Seeing severely assaulted victims | 215 (82.7) | 77 (77.8) | 14.0 (13.3) | 10.0 (11.2) | 1.4 (1.3) | 2.2 (2.1) |

| Seeing victims of a homicide | 185 (71.2) | 58 (58.6) | 5.5 (6.2) | 3.7 (2.8) | 3.1 (2.8) | 4.0 (3.0) |

| Other | 66 (26.1) | 36 (39.6) | 13.3 (17.6) | 19.8 (45.8) | 2.1 (2.3) | 2.4 (3.0) |

| Mean (SD) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.1 (2.1) | ||||

Figure 1.

Occurrence of different types of traumatic events by sex.

The mean PCL-C score was 25.7 for men and 27.1 for women (Table 3). Using the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs recommended diagnostic cutoff score of 33 or above, 15.0% of men and 18.2% of women had PTSD. Levels of PTSD symptomatology were generally similar between men and women with officers reporting high levels of re-experiencing the traumatic event and hyperarousal and lower levels of avoidance and numbing. Using the clustering approach, 10% of men and 9.1% of women had partial PTSD and 5.8% of men and 7.1% of women had full PTSD.

Table 3.

Summary measures for the PTSD Checklist- Civilian by sex.

| PCL-C | Score or Criteria | Prevalence N (%) | Mean (SD) | Range of Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |||

| Total PCL-C | 25.7 (8.5) | 27.1 (9.2) | 0 – 85 | |||

| ≥ 25 | 116 (44.6) | 48 (48.5) | 32.6 (8.4) | 33.8 (9.2) | ||

| Full PTSD | ≥ 33 | 39 (15.0) | 18 (18.2) | 42.2 (8.0) | 42.6 (9.7) | |

| ≥ 44 | 13 (5.0) | 6 (6.1) | 51.8 (5.7) | 53.3 (10.0) | ||

| Clustering Approach | ||||||

| Score of ≥3 on | ||||||

| Cluster B: Re-experiencing | 1 of 5 Questions | 57 (21.9) | 26 (26.3) | 7.2 (2.9) | 7.9 (3.7) | 0 – 25 |

| Cluster C: Avoidance/Numbing | 3 of 7 Questions | 27 (10.4) | 10 (10.1) | 9.7 (3.5) | 10.0 (3.4) | 0 – 35 |

| Cluster D: Arousal | 2 of 5 Questions | 61 (23.5) | 23 (23.2) | 8.8 (3.2) | 9.3 (3.4) | 0 – 25 |

| Yes for | ||||||

| Partial PTSD | 2 of 3 Clusters | 26 (10.0) | 9 (9.1) | 35.2 (5.4) | 35.3 (3.4) | |

| Full PTSD | 3 of 3 Clusters | 15 (5.8) | 7 (7.1) | 49.7 (7.1) | 51.4 (10.5) | |

The association between traumatic event type and frequency and PTSD symptomatology was assessed separately for men and women (Table 4). In female officers, a significant and positive association was found for ‘involvement in a shooting incident’ and PCL-C scores. The association remained significant after covariate adjustment for age, race/ethnicity and education. The mean PCL-C score for those women who experienced this event was 11 points higher than for those women who did not experience the event (36.5 vs. 25.5; p-value = 0.003). No associations were found in male officers.

Table 4.

Multivariate-adjusted* mean PCL-C scores by frequency of traumatic events and sex.

| Traumatic Event | Men

|

Women^

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | |

| The shooting of another officer | ||||

| 0 times | 222 | 25.4 (0.8) | -- | |

| ≥1 times | 25 | 23.6 (1.8) | -- | |

| p-value** | 0.33 | |||

| Your involvement in a shooting incident | ||||

| 0 times | 223 | 25.2 (0.8) | 91 | 25.5 (1.7) |

| ≥1 times | 21 | 25.3 (1.9) | 7 | 36.5 (3.8) |

| p-value | 0.98 | 0.003 | ||

| Seeing abused children | ||||

| 0 times | 86 | 24.9 (1.0) | 34 | 24.7 (2.3) |

| 1–4 times | 86 | 24.7 (1.0) | 31 | 25.3 (2.2) |

| ≥5 times | 75 | 26.2 (1.2) | 33 | 27.6 (2.2) |

| p-value | 0.35 | 0.23 | ||

| Seeing victims of a serious traffic accident | ||||

| 0 times | 86 | 24.6 (1.0) | 37 | 25.2 (2.1) |

| 1–2 times | 46 | 23.6 (1.4) | 30 | 25.9 (2.3) |

| ≥3 times | 115 | 26.3 (1.0) | 31 | 26.7 (2.3) |

| p-value | 0.19 | 0.53 | ||

| Seeing someone die in front of you | ||||

| 0 times | 154 | 25.7 (0.8) | 75 | 25.7 (1.8) |

| ≥1 times | 94 | 23.9 (1.1) | 21 | 26.2 (2.5) |

| p-value | 0.11 | 0.85 | ||

| Seeing dead bodies | ||||

| 0 times | 35 | 24.6 (1.6) | 19 | 24.1 (2.7) |

| 1–5 times | 126 | 25.4 (0.9) | 42 | 25.9 (2.2) |

| ≥6 times | 87 | 25.0 (1.1) | 36 | 26.5 (2.1) |

| p-value | 0.84 | 0.40 | ||

| Seeing severely assaulted victims | ||||

| 0 times | 39 | 26.2 (1.5) | 21 | 26.1 (2.6) |

| 1–10 times | 119 | 24.2 (0.9) | 53 | 24.9 (2.1) |

| ≥11 times | 89 | 25.7 (1.1) | 20 | 27.6 (2.7) |

| p-value | 0.75 | 0.66 | ||

| Seeing victims of a homicide | ||||

| 0 times | 64 | 24.8 (1.2) | 40 | 25.5 (2.0) |

| 1–2 times | 63 | 24.7 (1.2) | 24 | 24.1 (2.5) |

| ≥3 times | 120 | 24.6 (1.0) | 33 | 27.7 (2.3) |

| p-value | 0.55 | 0.34 | ||

| Total Occurrence | ||||

| 0–3 events | 60 | 25.2 (1.2) | 36 | 24.6 (2.1) |

| 4–5 events | 100 | 25.4 (1.0) | 30 | 25.5 (2.2) |

| 6–9 events | 88 | 24.8 (1.1) | 32 | 28.2 (2.3) |

| p-value | 0.82 | 0.12 | ||

Multivariable models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and education.

p-values are from linear contrasts.

Cell sizes too small to report for women.

Further stratification by reported workload (low or moderate vs. high), exposure to prior trauma, and military service was conducted (Table 5). Among women with a high workload, a significant and positive association was found between overall event occurrence and PCL-C score. As the number of traumatic events increased (range 0–9) the PCL-C score increased (p-value = 0.028). Similarly among women with a high workload, being involved in a shooting was positively associated with PCL-C scores (p-value < 0.001). However, the number of women who experienced the event was low (n = 5). No associations were found in male officers. Among women officers without prior trauma exposure, significant and positive associations were found between seeing ‘abused children’ (p-value = 0.021) and ‘homicide victims’ (p-value = 0.017) and PCL-C scores; the associations were slightly attenuated by multivariable adjustment (p-values = 0.030 and 0.035, respectively). No associations were found in male officers. Significant associations for male and female officers were found after stratifying on military service. For women without military service, a significant and positive association was found for overall event occurrence and for involvement in a shooting and PCL-C score. In men without military service, as the frequency of seeing abused children increased so did the PCL-C score (p-value = 0.041).

Table 5.

Multivariate-adjusted* mean PCL-C scores by frequency of traumatic events, sex, workload, prior trauma and military service

| Traumatic Event | Men

|

Women

|

Men^

|

Women^

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | |

| Workload | High Workload | Low or Moderate Workload | ||||||

| Involvement in a shooting incident | ||||||||

| 0 times | 149 | 25.2 (0.9) | 43 | 25.6 (2.2) | ||||

| ≥1 time | 18 | 24.5 (2.1) | 5 | 40.2 (4.5) | -- | -- | ||

| p-value | 0.77 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Prior Trauma | No Prior Trauma | Prior Trauma | ||||||

| Seeing abused children | ||||||||

| 0 times | 32 | 22.5 (1.8) | 17 | 20.0 (2.9) | 31 | 28.2 (1.7) | 10 | 33.6 (5.6) |

| 1–4 times | 34 | 23.2 (1.8) | 12 | 24.1 (3.1) | 38 | 25.6 (1.5) | 11 | 26.2 (4.8) |

| ≥5 times | 34 | 26.3 (1.9) | 15 | 25.7 (2.5) | 26 | 24.5 (1.9) | 9 | 32.3 (5.5) |

| p-value | 0.10 | 0.030 | 0.11 | 0.84 | ||||

| Seeing victims of a homicide | ||||||||

| 0 times | 24 | 22.5 (2.0) | 20 | 20.8 (2.7) | 25 | 27.6 (2.0) | 12 | 32.3 (5.0) |

| 1–2 times | 28 | 25.0 (2.0) | 10 | 21.6 (3.4) | 26 | 24.0 (1.8) | 10 | 27.8 (5.3) |

| ≥3 times | 49 | 24.2 (1.7) | 13 | 26.4 (2.6) | 43 | 27.4 (1.6) | 8 | 29.6 (5.7) |

| p-value | 0.47 | 0.035 | 0.92 | 0.66 | ||||

| Military Service | No Military Service | Military Service | ||||||

| Involvement in a shooting incident | ||||||||

| 0 times | 165 | 25.5 (1.0) | 81 | 25.9 (2.2) | 58 | 25.1 (1.4) | ||

| ≥1 time | 16 | 26.5 (2.3) | 6 | 40.4 (4.2) | 5 | 22.5 (4.1) | -- | |

| p-value | 0.66 | <0.001 | 0.57 | |||||

| Seeing abused children | ||||||||

| 0 times | 61 | 24.6 (1.3) | 29 | 23.7 (2.9) | 25 | 26.6 (1.9) | -- | |

| 1–4 times | 62 | 25.0 (1.2) | 29 | 24.8 (2.9) | 24 | 24.4 (2.0) | -- | |

| ≥5 times | 59 | 27.7 (1.4) | 29 | 28.7 (2.6) | 16 | 22.4 (2.3) | -- | |

| p-value | 0.041 | 0.06 | 0.15 | |||||

| Total Occurrence | ||||||||

| 0–3 events | 40 | 25.4 (1.6) | 30 | 23.8 (2.8) | 20 | 25.4 (2.2) | -- | |

| 4–5 events | 73 | 25.4 (1.3) | 28 | 25.9 (2.8) | 27 | 26.0 (1.8) | -- | |

| 6–9 events | 70 | 25.7 (1.3) | 29 | 29.2 (2.7) | 18 | 22.1 (2.3) | -- | |

| p-value | 0.85 | 0.034 | 0.31 | |||||

Multivariable models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and education.

p-values are from linear contrasts.

Cell sizes too small to report men and women with low to moderate workload and women with military service.

Associations between time since last event occurrence and PCL-C scores were compared separately for men and women (Table 6). A significant association was found in male officers for the traumatic event of seeing severely assaulted victims. PCL-C scores were higher for men who had more recently experienced the event (in the last month) compared to those who experienced the event two or more months ago (26.5 vs. 22.8; p-value = 0.009). This association remained significant after multivariable adjustment (p-value = 0.016). No associations were found in female officers.

Table 6.

Multivariate-adjusted* mean PCL-C scores by recency of traumatic events and sex.

| Traumatic Event | Men

|

Women

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | |

| The shooting of another officer | ||||

| 0–3 months ago | 9 | 22.3 (3.6) | -- | |

| 4 or more months ago | 13 | 24.3 (3.9) | -- | |

| p-value** | 0.63 | |||

| Your involvement in a shooting incident | ||||

| 0–2 months ago | 12 | 24.6 (4.0) | -- | |

| 3 or more months ago | 7 | 20.8 (4.8) | -- | |

| p-value** | 0.44 | |||

| Seeing abused children | ||||

| 0–1 month ago | 69 | 25.0 (1.4) | 31 | 26.2 (2.2) |

| 2 or more months ago | 86 | 25.3 (1.2) | 32 | 26.4 (2.0) |

| p-value** | 0.83 | 0.91 | ||

| Seeing victims of a serious traffic accident | ||||

| 0–1 month ago | 66 | 25.3 (1.4) | 27 | 24.9 (2.1) |

| 2 or more months ago | 90 | 25.4 (1.3) | 34 | 25.5 (2.5) |

| p-value** | 0.97 | 0.79 | ||

| Seeing someone die in front of you | ||||

| 0–5 months ago | 58 | 25.4 (1.8) | 11 | 25.7 (4.7) |

| 6 or more months ago | 32 | 22.7 (2.0) | 10 | 25.9 (3.8) |

| p-value** | 0.15 | 0.96 | ||

| Seeing dead bodies | ||||

| 0–2 months ago | 142 | 26.0 (1.0) | 53 | 25.2 (1.8) |

| 3 or more months ago | 60 | 24.0 (1.3) | 25 | 26.2 (2.2) |

| p-value** | 0.16 | 0.63 | ||

| Seeing severely assaulted victims | ||||

| 0–1 month ago | 150 | 26.2 (1.0) | 40 | 26.2 (2.4) |

| 2 or more months ago | 45 | 22.6 (1.4) | 33 | 24.6 (2.4) |

| p-value** | 0.016 | 0.42 | ||

| Seeing victims of a homicide | ||||

| 0-2 months ago | 100 | 26.1 (1.2) | 25 | 26.7 (2.6) |

| 3 or more months ago | 75 | 24.8 (1.3) | 32 | 25.2 (2.6) |

| p-value** | 0.39 | 0.50 | ||

Multivariable models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and education.

p-values are from linear contrasts.

Cell size too small to report for women.

Further stratification by workload revealed no significant associations. Time since seeing dead bodies and PCL-C score was significantly associated in men with prior trauma exposure. PCL-C scores were higher when the event occurred in the last two months compared to three or more months ago (p-value = 0.021). Among men without military service, a significant and inverse association was found between time since seeing severely assaulted victims and PCL-C score (p-value = 0.043).

DISCUSSION

In the current study, police officers experienced numerous types of police-specific traumatic events with 60.1% of men and 46.4% of women witnessing or being involved in five or more different events in the past year. Over three-quarters of officers reported a traumatic event occurring in the last month. The nature of police work necessitates exposure to trauma so the high frequency of traumatic events in the current study is not surprising and is supported by other studies. Kaufmann et al. (2013) found a higher prevalence of traumatic events among protective service workers than other occupations. Patterson (2001) found that police officers experience approximately 3.5 traumatic events in a six-month period. Most often, the events reported in this study involved witnessing sad and depressing events, such as adults and children who were severely injured or died from abuse, assault or traffic accidents. Kaufmann et al. (2013) found seeing someone severely injured or dead was the most common event experienced by protective service workers. Yet, only 30% of those workers reported this event occurring, whereas, over 80% of the officers in the current study experienced these events.

The prevalence of PTSD in this study was approximately 15% for men and 18% for women using the PCL-C cut point of 33 and higher. This cut point has been previously used by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs for PTSD screening in primary care clinic settings and is recommended for use in civilian primary care and general population samples (National Center for PTSD, 2011). The prevalence is similar to that reported among New Orleans police officers after Hurricane Katrina (19%) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2006) and professional German firefighters (18.2%) (Wagner, Heinrichs & Ehlert, 1998).

Alternatively, Maia and colleagues (2007) recommended following the clinical diagnostic model when diagnosing PTSD. When using this approach, the prevalence of partial PTSD was 10% in men and 9.1% in women, slightly lower than previous studies of police officers (Maia et al., 2007; Pietrzak et al., 2012). The prevalence of full PTSD was 5.8% in men and 7.1% in women. These values are slightly lower than those reported by Maia et al. (2007) and similar to those found in Dutch police officers (Carlier et al., 1997) and police officers who responded to the World Trade Center attacks (Pietrzak et al., 2012). Re-experiencing the event and hyperarousal were more common than avoidance symptoms, similar to the findings of Perrin et al. (2007) in World Trade Center workers.

The prevalence of PTSD was similar between male and female police officers. Prior studies in the general population have found a higher PTSD prevalence in women compared to men, yet gender differences have not been found when the samples were among police officers and military personnel (Lilly et al., 2009; Pole et al., 2001; Sutker, David, Uddo & Ditta, 1995). Lilly et al. (2009) also found that female police officers reported less severe PTSD symptoms than female civilians. Reasons for this may include the self-selection of women into a law enforcement career, perhaps these women are better prepared or more able to handle exposure to traumatic events. Female officers may feel the need to conform to the norms of their male counterparts by suppressing their emotions (Lilly et al., 2009).

In the current study, significant associations were found between frequency of traumatic events and PTSD symptoms in female officers. While a small number of female officers reported being involved in a shooting, their levels of PTSD symptomatology were 11 points higher than female officers who were not involved in a shooting. Women are more likely to develop PTSD after a traumatic event than men (Gavranidou & Rosner, 2003; Breslau et al., 1999). Due to the infrequency of this event for female officers, it may not be surprising that the event would have a significant impact. When the associations between traumatic event frequency and PTSD symptoms were stratified by prior trauma (both history of any type of prior trauma and specifically military service), significant differences were found for women without a history of prior trauma or military experience and for men without prior trauma. One reason for this association may be lack of prior trauma exposure, which may increase vulnerability to psychological disorders. Kaufmann et al. (2013) found a significant association between traumatic event exposure and incident psychological distress among early career police officers, who may also have little prior exposure to traumatic events. It is also possible that these officers may feel pressure to conform to the cultural norm for police officers where requesting mental health assistance may be viewed as a weakness.

The significant associations found in this study involved stressful and potentially life-threatening events for police officers, such as being involved in a shooting. No associations were found for events in which an officer was passively involved with the exception of seeing child abuse and homicide victims. Police training prepares officers for exposure to grotesque events, such as seeing dead bodies or traffic accident victims. Yet, officers may lack training in how to handle more difficult and stressful events such as seeing abused children or events where the officer may be harmed. Traumatic event severity has been associated with increased risk of PTSD (Carlier, Lamberts, & Gersons, 1997). Child abuse may be particularly difficult for police officers who can personally relate to the victim, i.e. having children or grandchildren of the same age. McCaslin and colleagues (2006) found that traumatic events involving high personal threat, including shooting incidents, were associated with increased psychological distress.

Associations between recency of traumatic event occurrence and PCL-C symptoms were found in male but not female police officers. Male officers who saw severely assaulted victims in the past month had a four point higher PCL-C score than male officers who witnessed these victims two or more months ago. Of the different types of traumatic events, seeing severely assaulted victims was the most recent event reported for male police officers (mean occurrence = 1.4 months ago). Brauchle (2006) also reported higher PTSD in police officers at six weeks compared to six months after an Austrian tunnel fire. Increased PTSD symptoms, such as re-experiencing the event and hyperarousal, may be expected immediately after a traumatic event as part of the natural trauma response or if symptoms last for several days to a month may indicate an acute stress response (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Limitations of this study are noteworthy. The cross-sectional study design prevents us from making conclusions about causality. PTSD symptoms could be elevated due to other traumatic exposures, whether it was a police-related event that occurred two years ago or a recent event that occurred outside of work (i.e. death of a family member). The Police Incident Survey only captured exposure to eight types of police-specific traumatic events. However, the survey was developed by Violanti and Gherke (2004) using prior research of traumatic events identified by police officers. Also, the scale provides an opportunity for officers to list any other traumatic events that occurred over the past year in an open-ended question and we included the frequency of those events in our analysis.

Strengths of this study include the use of a widely used measure of PTSD symptoms: the PCL-C. The PCL has been shown to highly correlate with clinical-administered measures (Norris & Hamblen, 2004) and the symptoms included map directly to the DSM-V criteria (American Psychological Association, 2013). We were able to calculate the prevalence of PTSD using two methods: 1) numerical cut point recommended by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD (2011) for use in general population samples and in primary care settings, and 2) clustering approach developed by Maia et al. (2007). The clustering approach follows the DSM-V diagnostic approach and provided an opportunity to compare the prevalence rates of partial and full PTSD to other studies of police officers. The Police Incident Survey provided an opportunity to assess both frequency of traumatic event exposure and recency of event occurrence, a limitation noted in prior studies (Maia et al., 2007). Differences between male and female police officers in terms of event exposure and separately PTSD prevalence have been previously examined. This is one of the only studies to examine the association between police-specific traumatic events and PTSD symptoms separately for male and female police officers.

In conclusion, higher PTSD symptoms were found in women officers with more exposure to abused children and homicide victims. This association was strongest in those women without a history of prior trauma. No association was found between the frequency of events and PTSD symptoms in male officers. However, male officers who most recently witnessed victims of severe assault had higher PTSD symptoms than those men who had experienced this event two or more months ago. The findings are important for understanding the role of police-specific traumatic events in the development of PTSD in a high-risk, highly stressed occupational group. Future longitudinal assessment of this association is warranted and should also include the contribution of non-work factors, such as traumatic life events, and thorough assessment of personal trauma before police work.

Table 7.

Multivariate-adjusted* mean PCL-C scores by recency of traumatic events, sex, military status and prior trauma.

| Traumatic Event | Men

|

Women

|

Men

|

Women^

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | N | Mean (SE) | |

| Prior Trauma | No Prior Trauma | Prior Trauma | ||||||

| Seeing dead bodies | ||||||||

| 0–2 months ago | 62 | 24.4 (1.8) | 23 | 24.6 (2.9) | 52 | 27.8 (1.5) | 15 | 27.8 (3.6) |

| 3 or more months ago | 23 | 23.1 (2.5) | 9 | 22.9 (3.8) | 25 | 22.8 (1.9) | 11 | 23.2 (4.6) |

| p-value | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.021 | 0.33 | ||||

| Military Service | No Military Service | Military Service | ||||||

| Seeing severely assaulted victims | ||||||||

| 0–1 month ago | 114 | 26.8 (1.3) | 35 | 26.8 (2.5) | 36 | 25.8 (1.5) | -- | |

| 2 or more months ago | 30 | 22.9 (1.9) | 32 | 24.7 (2.4) | 15 | 20.8 (2.2) | -- | |

| p-value | 0.043 | 0.31 | 0.05 | |||||

Multivariable models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity and education.

p-values are from linear contrasts.

Cell size too small to report for women with military service.

Acknowledgments

Sources of funding: this work was supported by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Contract Number 200-2003-01580.

Footnotes

Disclaimer: The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Contributor Information

Tara A. Hartley, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Morgantown, WV

Khachatur Sarkisian, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Morgantown, WV.

John M. Violanti, University at Buffalo, Buffalo, NY The State University of New York, Buffalo, NY

Michael E. Andrew, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Morgantown, WV

Cecil M. Burchfiel, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, Ctrs. for Disease Control & Prevention, Morgantown, WV

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, Fifth Edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Austin-Ketch TL, Violanti J, Fekedulegn D, Andrew ME, Burchfiel CM, Hartley TA. Addictions and the criminal justice system, what happens on the other side? Post-traumatic stress symptoms and cortisol measures in a police cohort. Journal of Addictions Nursing. 2012;23(1):22–29. doi: 10.3109/10884602.2011.645255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauchle G. Incidence- and reaction-related predictors of the acute and posttraumatic stress disorder in disaster workers. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie. 2006;52(1):52–62. doi: 10.13109/zptm.2006.52.1.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Chilcoat HD, Kessler RC, Davis GC. Previous exposure to trauma and PTSD effects of subsequent trauma: Results from the Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:902–907. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.6.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlier IV, Lamberts RD, Gersons BP. Risk factors for posttraumatic stress symptomatology in police officers: a prospective analysis. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disorders. 1997;185(8):498–506. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199708000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Hazard Evaluation of police officers and firefighters after Hurricane Katrina – New Orleans, Louisiana, October 17–28 and November 30-December 5, 2005. Morbidity & Mortality Weekley Report. 2006;55:456–458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colwell LH. Police officers’ experience with trauma. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2009;11(1):3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gavranidou M, Rosner R. The weaker sex? Gender and post-traumtic stress disorder. Depression & Anxiety. 2003;17:130–139. doi: 10.1002/da.10103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgins GA, Creamer M, Bell R. Risk factors for posttrauma reactions in police officers: a longitudinal study. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2001;189(8):541–547. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javidi H, Yadollahie M. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. International Journal of Occupational & Environmental Medicine. 2012;3(1):2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann CN, Rutkow L, Spira AP, Mojtabai R. Mental Health of Protective Services Workers: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Disaster Medicine & Public Health Preparedness. 2013;7:36–45. doi: 10.1001/dmp.2012.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly M, Pole N, Best S, Metzler T, Marmar C. Gender and PTSD: What can we learn from female police officers? Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2009;23:767–774. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2009.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukaschek K, Baumert J, Kruse J, Emeny RT, Lacruz ME, Huth C, …KORA Investigators. Relationship between posttraumatic stress disorder and type 2 diabetes in a population-based cross-sectional study with 2970 participants. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2013;74(4):340–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maia DB, Marmar CR, Metzler T, Nobrega A, Berger W, Mendlowicz MV, …Figueira I. Posttraumatic stress symptoms in an elite unite of Brazilian police officers: Prevalence and impact on psychosocial functioning and on physical and mental health. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaslin SE, Rogers CE, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Weiss DS, Fagan JA, … Marmar CR. The impact of personal threat on police officers’ responses to critical incident stressors. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2006;194(8):591–597. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000230641.43013.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for PTSD. PTSD Checklist (PCL) 2011 Retrieved October 31, 2011, from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/pages/assessments/ptsd-checklist.asp.

- National Center for PTSD. What is PTSD? 2013 Retrieved September 25, 2013, from http://www.ptsd.va.gov/public/pages/what-is-ptsd.asp.

- Neylan TC, Metzler TJ, Best SR, Weiss DS, Fagan JA, Liberman A, … Marmar CR. Critical incident exposure and sleep quality in police officers. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2002;64:345–352. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH, Hamblen JL. Standardized self-report measures of civilian trauma and PTSD. In: Wilson JP, Keane TM, editors. Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2004. pp. 79–80. [Google Scholar]

- North CS, Tivis L, McMillen JC, Pfefferbaum B, Cox J, Spitznagel EL, … Smith EM. Coping, functioning, and adjustment of rescue workers after the Oklahoma City bombing. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2002;15(3):171–175. doi: 10.1023/A:1015286909111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacella ML, Hruska B, Delahanty DL. The physical health consequences of PTSD and PTSD symptoms: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2013;27(1):33–46. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GT. The relationship between demographic variables and exposure to traumatic incidents among police officers. Australian Journal of Disaster & Trauma Studies. 2001 http://www.massey.ac.nz/~trauma/issues/2001-2/patterson2.htm.

- Perrin MA, DiGrande L, Wheeler K, Thorpe L, Farfel M, Brackbill R. Differences in PTSD prevalence and associated risk factors among World Trade Center disaster rescue and recovery workers. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1385–1394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06101645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak RH, Schechter CB, Bromet EJ, Katz CL, Reissman DB, Ozbay F, … Southwick SM. The burden of full and subsyndromal posttraumatic stress disorder among police involved in the World Trade Center rescue and recovery effort. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2012;46(7):835–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pole N, Best SR, Weiss DS, Metzler T, Liberman AM, Fagan J, Marmar CR. Effects of gender and ethnicity on duty-related posttraumatic stress symptoms among urban police officers. Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease. 2001;189:442–448. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sledjeski EM, Speisman B, Dierker LC. Does number of lifetime traumas explain the relationship between PTSD and chronic medical conditions? Answers from the National Comorbidity Survey-Replication (NCSR) Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;31(4):341–349. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9158-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stellman JM, Smith RP, Katz CL, Sharma V, Charney DS, Herbert R, … Southwick S. Enduring mental health morbidity and social function impairment in World Trade Center rescue, recovery, and cleanup workers: The psychological dimension of an environmental health disaster. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2008;116(9):1248–1253. doi: 10.1289/ehp.11164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart H. Suicidality among police. Current Opinions Psychiatry. 2008;21(5):505–509. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e328305e4c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutker PB, Davis JM, Uddo M, Ditta SR. Assessment of psychological distress in Persian Gulf troops: Ethnicity and gender comparisons. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1995;64:415–427. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6403_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JH, Neylan TC, Schiller NB, Li Y, Cohen BE. Objective evidence of myocardial ischemia in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biolological Psychiatry. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Violanti JM, Gehrke A. Police trauma encounters: precursors of compassion fatigue. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health. 2004;6(2):75–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Heinrichs M, Ehlert U. Prevalence of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder in German professional firefighters. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1727–1732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.155.12.1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weathers FW, Litz BT, Herman DS, Huska JA, Keane TM. The PTSD Checklist (PCL): Reliability, validity, and diagnostic utility. Paper presented at the Annual Convention of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies; San Antonio, TX. 1993. [Google Scholar]