Abstract

Candidatus Neoehrlichia is increasingly being recognized worldwide as a tickborne pathogen. We report a case of symptomatic neoehrlichiosis in an immunocompetent Austria resident who had recently returned from travel in Tanzania. The use of Anaplasmataceae-specific PCR to determine the duration of antimicrobial therapy seems reasonable to avert recrudescence.

Keywords: Candidatus Neoehrlichia, Austria, imported, tick-borne, tickborne, travel-associated, neoehrlichiosis, human, Anaplasmataceae-specific PCR, diagnosis, therapeutic guidance, bacteria, immunocompetent

Human neoehrlichiosis is an infectious disease that primarily affects immunocompromised persons and persons with severe concurrent medical conditions (1–5). We describe symptomatic Candidatus Neoehrlichia infection in an otherwise healthy woman who had returned from a 28-day vacation in Tanzania, and we illustrate the applicability of Anaplasmataceae-specific PCR for diagnosis and therapeutic guidance.

The Study

In January 2013, a 30-year-old white woman with no relevant medical history was admitted to the Division of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, General Hospital of Vienna, in Vienna, Austria, because of a 3-week history of high fevers (up to 39.9°C), chills, and night sweats accompanied by headache, muscle pain, and malaise. Four weeks before hospitalization, the woman had returned from a 28-day vacation in Tanzania. She had not taken antimalarial prophylaxis drugs while in Tanzania; instead she carried atovaquone/proguanil tablets as a standby medication. The woman felt well during the entire stay in Tanzania, so she did not take the atovaquone/proguanil.

Spiking fevers began 5 days after her return to Vienna. She visited the outpatient clinic at the General Hospital of Vienna, where malaria, Dengue virus fever, and typhoid fever were ruled out as causative diseases. During her first days in Tanzania, the woman had voluntary skin contact with a prosimian, but she recalled no recent tick bites or exposures to animals. Blood samples were obtained; multiple cultures were negative. However, over the next 10 days, persistent fever and a deteriorating general condition led to hospitalization for further evaluation. Clinical data at admission and results of primary diagnostic tests are provided in the Table.

Table. Clinical data at admission and primary diagnostic test results for a patient with Candidatus Neoehrlichia infection, Austria, 2013*.

| Clinical variable | Finding/value |

|---|---|

| Subjective symptoms |

Malaise, diffuse muscle pain, dull headache (without signs of meningism), and tenderness in the left upper abdominal quadrant |

| Tympanic temperature |

37.8°C, while taking acetaminophen |

| Heart auscultation |

Systolic murmur (right sternal border), tachycardia (125 beats per minute) |

| Condition of skin |

No rash or signs of cutaneous exposure to arthropods |

| Laboratory testing† | |

| C-reactive protein | 5 mg/dL (<0.5) |

| Procalcitonin | 0.14 ng/mL (<0.5) |

| Leukocyte count | 3.9 × 109/L (4–10) |

| Neutrophils | 53% (50–75) |

| Lymphocytes | 27% (25–40) |

| Monocytes | 16% (0–12) |

| Fibrinogen | 480 mg/dL (180–390) |

| Serum amyloid A | 164 mg/L (<5) |

| γ-globulins | 26.2% (11.1–18.8) |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | 70 mm/h (<15) |

| Platelet count | 121 × 109/L (150–350) |

| Hemoglobin |

9 g/dL (12–16) |

| Chest radiography |

No consolidations, no opacities |

| Abdominal ultrasonography |

Splenomegaly of 15.5 x 6.7 cm |

| Transesophageal echocardiography |

Normal cardiac function and valves, no evidence of vegetations |

| Cranial computed tomography |

Parasagittal meningioma, otherwise normal |

| Ophthalmologic examination |

Bilateral papilloedema |

| Cerebrospinal fluid |

Clear and colorless; absolute cell count 4/μL protein, glucose, and lactate levels within reference range |

| Abdominal ultrasonography |

Splenomegaly, 15.5 × 6.7 cm |

| Urinary dip stick and urinary cultures |

No growth |

| Blood cultures |

No growth |

| Serologic testing | |

| HIV | Negative |

| Hepatitis B and C viruses | Negative |

| Epstein-Barr virus | Negative |

| Cytomegalovirus | Negative |

| Mycoplasma spp. | Negative |

| Adenovirus | Negative |

| Enterovirus | Negative |

| Coxsackievirus | Negative |

| Influenza A,B, and C viruses | Negative |

| Parainfluenza virus | Negative |

| Anaplasma spp. | Negative |

| Rickettsia spp. | Negative |

| Tuberculous mycobacteria | Negative |

| Plasmodium spp. | Negative |

| Syphilis (VDRL, TPPA) |

Negative |

| PCR testing | |

| Leishmania spp. | Negative |

| Trypanosoma spp. | Negative |

|

Plasmodium spp. |

Negative |

| Giemsa-stained thin and thick blood smears | |

| Plasmodium spp. | Negative |

*TPPA, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination assay; VDRL, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test. †Laboratory data are given as absolute number or percentage (reference range).

During the first days of hospitalization, the woman had fever (up to 39°C) accompanied by general discomfort and headache. Giemsa-stained thick and thin blood smears showed no evidence of malaria. Likewise, serologic and PCR test results for Plasmodium spp. were negative.

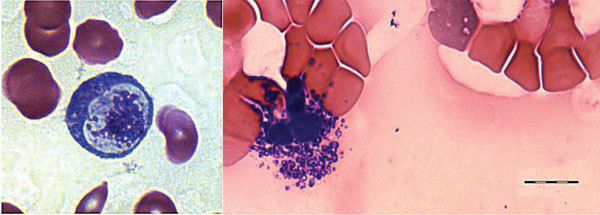

On hospitalization day 5, a peripheral blood sample was tested by using a 16S rRNA gene–based eubacterial broad range PCR (SepsiTest; Molzym GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany); results were positive. The amplification products (300 bp) were sequenced (GenBank accession no. KT895260) and compared, using BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi), with known sequences in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) database. The sequence showed 98% (294/300 bp) homology with Candidatus Neoehrlichia lotoris (GenBank accession no. EF633744.1; only 1 database entry was available) and 97% (293/301 bp) homology with Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis (GenBank accession no. KF155504.1; several database entries were available and showed a reproducible single base deletion at position 225). These findings were confirmed by Anaplasmataceae-specific 16S ribosomal RNA gene–based PCR. Primer pairs EHR16SD (5′-GGT ACC YAC AGA AGA AGT CC-3′) and EHR16SR (5′-TAG CAC TCA TCG TTT ACA GC-3′) were chosen to amplify a 345-bp fragment (6). The protocol was adjusted to that in the manual for High-Fidelity PCR enzyme mix (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and to that of Brown et al. (7). Bidirectional sequencing of the 345-bp amplicon showed a sequence of 243 bp corresponding to the cDNA strand (GenBank accession no. KT953340) and yielded similar results: 97% (235/243 bp) sequence homology was shared with Candidatus Neoehrlichia lotoris (GenBank accession no. EF633744.1), and 96% (235/244 bp) sequence homology was shared with Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis (GenBank accession no. JQ359046.1). Because the percentages of shared homologies were not sufficient to attribute the identified microbial agent to an official species, we tentatively named the agent Candidatus Neoehrlichia Tanzania. In addition, a microscopy review of Giemsa-stained blood smears obtained within the first days of admission showed structures possibly equivalent to microbial pathogens within leukocytes (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Giemsa-stained blood smear from an immunocompetent patient with Candidatus Neoehrlichia infection, Austria, 2013. The blood smear shows possible microbial pathogens within leukocytes. Scale bar indicates 10 μm.

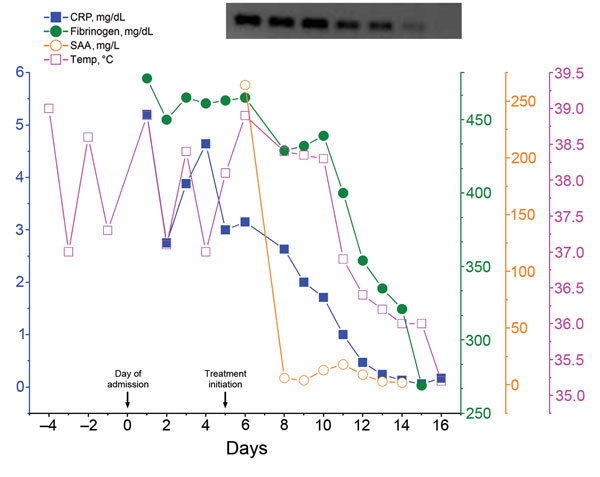

Antimicrobial treatment with oral doxycycline (300 mg per day) was subsequently initiated, resulting in improvement in the patient’s overall condition within 2 days and in a continuous decrease of all inflammation markers, normalization of platelet counts, and abatement of fever (Figure 2). However, serum Neoehrlichia DNA remained detectable at high levels. To provide the optimal duration of antibiotic treatment, we performed daily Anaplasmataceae-specific 16S PCR measurements of blood samples. Over the next 10 days of therapy, the DNA signal intensity continuously diminished. Doxycycline was stopped 1 day after disappearance of Neoehrlichia serum DNA.

Figure 2.

Body temperature and markers of inflammation over the course of hospitalization for a patient with Candidatus Neoehrlichia infection, Austria, 2013. Day 0 indicates time of admission. Antimicrobial therapy with doxycycline (300 mg per day) was begun on day 5 and led to a rapid resolution of clinical symptoms and a progressive decrease of all inflammatory parameters. Daily Anaplasmataceae-specific PCR measurements guided therapy, which was safely stopped 1 day after disappearance of serum Candidatus Neoehrlichia DNA. Upper right shows 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis analysis. The intensity of the 345-bp DNA band amplified from blood samples progressively decreased over the course of treatment. CRP, C-reactive protein; SAA, serum amyloid A; Temp, tympanic temperature.

In contrast with patients in previously published reports of human neoehrlichiosis, the patient described in our report was a healthy young woman without concurrent medical conditions. She had signs and symptoms of disease for 4 weeks without any symptomatic improvement before therapy was initiated. Treatment led to a rapid clinical response and rapid clearance of serum Neoehrlichia DNA, which may be attributable to her otherwise good medical condition but may also reflect high antimicrobial efficiency of the high-dose therapeutic regimen applied.

Because symptomatic neoehrlichiosis usually occurs in patients with immunosuppression, we examined the patient for an underlying malignancy or autoimmune disorder. These conditions were largely ruled out by negative test results for HIV and mycobacteria and by a normal finding on 18F-FDG-PET/CT (18F-fluordeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography) examination (except for enhanced splenic FDG uptake). The patient had moderate disease with nonspecific symptoms partly resembling those of human anaplasmosis. The splenomegaly was attributed to polyclonal B cell activity (indicated by hypergammaglobulinemia), but it could also have resulted from direct infection of splenic sinusoidal cells, as found in Neoehrlichia-infected Wistar rats (8). However, spleen size decreased over the course of antimicrobial treatment and reached a normal diameter by a 3-week follow-up examination.

No evidence exists regarding the exact incubation period of human neoehrlichiosis, but it probably approximates that of human granulocytic anaplasmosis, suggesting that the patient in our study acquired neoehrlichiosis in Tanzania. Nonetheless, several tickborne diseases are highly endemic in Austria. Glatz et al. (9) recently reported a 4.2% prevalence of Candidatus Neoehrlichia in Ixodes ricinus ticks in Austria. However, in the 5-day period between returning home from Tanzania and fever onset, the patient in our study had stayed in the urban area of Vienna; thus, the possibility that she may have been exposed to ticks in Austria is limited but not excluded. Furthermore, the patient returned to Vienna at the height of winter, making the possible transmission of Candidatus Neoehrlichia by a domestic tick even less plausible. On the other hand, no epidemiologic data are available on the prevalence of Candidatus Neoehrlichia in ticks in Tanzania, but Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis was recently found in ticks of 2 species collected in Nigeria (10). Thus, the presence of Candidatus Neoehrlichia in ticks in Tanzania and the risk for transmission from ticks to humans seem conceivable. Because a 16S rDNA sequence difference of >2% is arbitrarily considered as indicative for delineation at the species level, it seems possible that a new Candidatus Neoehrlichia agent was detected in the patient in our study.

Conclusions

This case demonstrates that Candidatus Neoehrlichia can affect healthy persons who have no underlying hematologic or autoimmune disorders. Neoehrlichiosis should be considered in the differential diagnosis for patients with appropriate symptoms, independent of concurrent conditions and immune status. As long as no evidence-based recommendations regarding treatment of human neoehrlichiosis exist, it seems reasonable to use Anaplasmataceae-specific PCR to monitor treatment response and determine the duration of antimicrobial therapy to avert recrudescence.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patient in our study for giving consent to publish the data, Wolfgang Barousch for providing assistance with GenBank, and Albert Lalremruata for performing the Plasmodium spp. PCR.

Biography

Dr. Schwameis is an internal medicine resident at the Department of Clinical Pharmacology, Medical University of Vienna. His research interests include staphylococcal blood stream infections and infection-associated coagulopathy.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Schwameis M, Auer J, Mitteregger D, Simonitsch-Klupp I, Ramharter M, Burgmann H, et al. Anaplasmataceae–specific PCR for diagnosis and therapeutic guidance for symptomatic neoehrlichiosis in immunocompetent host. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2202.141762

References

- 1.Welinder-Olsson C, Kjellin E, Vaht K, Jacobsson S, Wenneras C. First case of human “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” infection in a febrile patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:1956–9. 10.1128/JCM.02423-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pekova S, Vydra J, Kabickova H, Frankova S, Haugvicova R, Mazal O, et al. Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis infection identified in 2 hematooncologic patients: benefit of molecular techniques for rare pathogen detection. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:266–70. 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2010.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.von Loewenich FD, Geissdorfer W, Disque C, Matten J, Schett G, Sakka SG, et al. Detection of “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” in two patients with severe febrile illnesses: evidence for a European sequence variant. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48:2630–5. 10.1128/JCM.00588-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grankvist A, Andersson PO, Mattsson M, Sender M, Vaht K, Hoper L, et al. Infections with the tick-borne bacterium “Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis” mimic noninfectious conditions in patients with B cell malignancies or autoimmune diseases. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1716–22. 10.1093/cid/ciu189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fehr JS, Bloemberg GV, Ritter C, Hombach M, Luscher TF, Weber R, et al. Septicemia caused by tick-borne bacterial pathogen Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:1127–9. 10.3201/eid1607.091907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Inokuma H, Raoult D, Brouqui P. Detection of Ehrlichia platys DNA in brown dog ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) in Okinawa Island, Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4219–21 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown GK, Martin AR, Roberts TK, Aitken RJ. Detection of Ehrlichia platys in dogs in Australia. Aust Vet J. 2001;79:554–8. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2001.tb10747.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawahara M, Rikihisa Y, Isogai E, Takahashi M, Misumi H, Suto C, et al. Ultrastructure and phylogenetic analysis of ‘Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis’ in the family Anaplasmataceae, isolated from wild rats and found in Ixodes ovatus ticks. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2004;54:1837–43. 10.1099/ijs.0.63260-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glatz M, Mullegger RR, Maurer F, Fingerle V, Achermann Y, Wilske B, et al. Detection of Candidatus Neoehrlichia mikurensis, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies and Anaplasma phagocytophilum in a tick population from Austria. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2014;5:139–44.http:// [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kamani J, Baneth G, Mumcuoglu KY, Waziri NE, Eyal O, Guthmann Y, et al. Molecular detection and characterization of tick-borne pathogens in dogs and ticks from Nigeria. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2108. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]