Abstract

During June 9–September 30, 2015, five cases of louseborne relapsing fever were identified in Turin, Italy. All 5 cases were in young refugees from Somalia, 2 of whom had lived in Italy since 2011. Our report seems to confirm the possibility of local transmission of louse-borne relapsing fever.

Keywords: Relapsing fever, Borrelia recurrentis, Italy, refugees, East Africa, lice, vector-borne infections, bacteria

Louseborne relapsing fever (LRF) was once widely distributed in all geographic areas, including Europe and North America, occurring in association with poverty and overcrowding. In Europe, it virtually disappeared after World War I in parallel with improved living conditions that led to substantially decreased body lice infestations in humans (1). Currently, LRF is reported mostly from Ethiopia and surrounding countries, where it is endemic (2): in this region, it is an extremely common infection with substantial mortality. The causative agent is the spirochete bacterium Borrelia recurrentis. In nature, the only relevant vector is the body louse, which feeds only on humans; no other reservoir for this infection is known (1,3). The incubation period is 3–12 days. We report 5 cases of LRF in refugees to Italy from East Africa that occurred during 2015.

The Cases

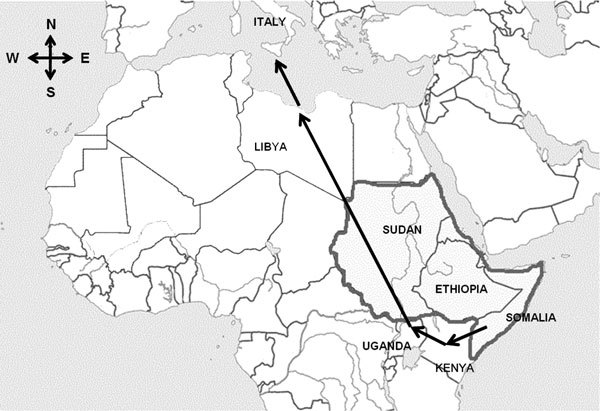

All 5 patients were young men from Somalia (Table). Patients 1, 4, and 5 had recently arrived in Italy after traveling from Somalia through Kenya, Uganda, and Sudan to Libya, where they boarded a boat to Sicily (Figure 1). Patients 2 and 3 had resided in Italy since 2011, and both denied any travel outside Europe in the past 4 years. These 2 men lived in the same building in Turin, occupied by ≈600 refugees of different nationalities, most of them from Somalia. Patients 4 and 5 also reported a short stay in the same building.

Table. Characteristics of louseborne relapsing fever among East African refugees, Italy, 2015*.

| Characteristic | Patient 1 | Patient 2 | Patient 3 | Patient 4 | Patient 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time from arrival in Italy | 3 d | 4 y | 3 y | 10 d | 10 d |

| Age, y | 20 | 27 | 31 | 20 | 26 |

| Date of admission | Jun 9 | Jul 28 | Sept 5 | Oct 1 | Sept 29 |

| Date of symptom onset |

Jun 7 |

Jul 24 |

Sept 1 |

Sept 27 |

Sept 26 |

| Symptom | |||||

| Fever | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Abdominal pain | No | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| Vomiting | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Diarrhea | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| Headache | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Myalgia | No | Yes | No | No | Yes |

| Other |

None |

Lumbar pain |

None |

Cough |

Chest pain, itching |

| Laboratory test (reference) | |||||

| Platelets (>150,000/μL) | 32,000 | 47,000 | 22,000 | 41,000 | 2,9000 |

| Bilirubin (<1.2 mg/dL) | 2.3 | 1.8 | 3.9 | 4.2 | 1.8 |

| Liver function† | Normal | Normal | AST ×4; ALT ×3 | AST ×3; ALT normal | Normal |

| Prothrombin time (>70%) | 78% | 66% | 68% | 100% | 70% |

| CRP† | ×16 | ×56 | ×95 | ×115 | ×59 |

| Procalcitonin (<0.5) | 11.36 | NA | 21 | 11.9 | NA |

| QTc (<440 msec) | 428 | 361 | 423 | 391 | 414 |

| PCR for Borrelia recurrentis |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

Positive |

| Treatment | Doxycicline | Doxycicline | Doxycicline | Doxicicline + ceftriaxone | Doxycicline, switched to ceftriaxone |

| Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction | Yes, mild | Not observed | Not observed | Not observed | Yes, moderate |

*ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRP, C-reactive protein; NA, not available; QTc, corrected QT interval. †Indicated as normal (within reference value) or × upper reference value.

Figure 1.

Route (arrows) followed by refugees from Somalia to Libya, where they boarded a boat to Sicily. Gray shading indicates Borrelia recurrentis–endemic countries.

All patients sought care at one of the city emergency departments (EDs), reporting a 2–4-day history of fever with chills and headache. Other common symptoms included vomiting, myalgia, and abdominal pain. One patient had diarrhea.

Routine blood exams, performed on all 5 men, showed marked thrombocytopenia (22,000–48,000/μL) and elevated C-reactive protein (values 16–115 times the upper reference value). Procalcitonin, measured in 3 patients, was markedly increased (11.4–21 ng/mL [reference <0.5 ng/mL]). Liver function tests and bilirubin were either normal or slightly elevated.

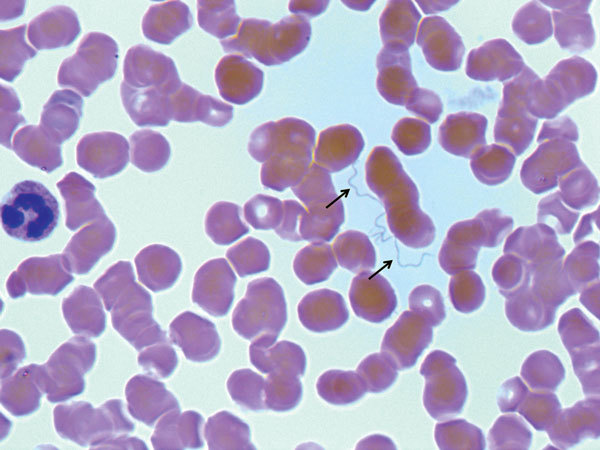

All patients were transferred to the Infectious Disease Hospital in Torino for further assessment. Giemsa-stained thin and thick blood smears were negative for malaria parasites but showed spirochetes (Figure 2). LRF was suspected, and the patients were treated with either doxycycline alone or doxycycline plus ceftriaxone. Patients 1 and 5 showed an acute febrile reaction after the first antimicrobial dose: symptoms were compatible with a Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction (JHR).

Figure 2.

Giemsa-stained thin blood smear showing spirochetes (arrows) in a 27-year-old male refugee from Somalia (patient 2) with louseborne relapsing fever, Italy, 2015. Original magnification ×1,000.

No lice were found on the patients or on their clothes; patient 5 had skin lesions caused by scratching. None of the patients had rash or bleeding as described in the literature (3). Hepatomegaly was not observed; only patient 4 showed an enlarged spleen at ultrasound. Tachycardia was common, but alterations of cardiac function were not observed (no murmurs, corrected QT interval in normal range). A low systolic blood pressure (<90 mm Hg) was observed only in patient 4.

Bacterial DNA was extracted from 200 μL of blood from each of the 5 patients by using the QIAmp Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany) and was detected amplifying the 16S rRNA. Nucleotide sequences of PCR products were determined. Sequences were identified by BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). B. recurrentis was identified in all patients, showing 100% identity with sequences of B. recurrentis reference strain A1 (GenBank accession nos. NR074866 and CP000993).

Italy has recently received large numbers of refugees from East Africa, particularly from Somalia. These refugees come from and travel through countries where B. recurrentis is endemic; along the way, they are often sheltered in crowded conditions with very poor hygienic facilities. Two of the patients reported here indicated that, while staying in Libya, they were held with many other persons in a close environment, and all refugees housed together reported severe itching.

Many of these refugees enter Italy through Sicily, from where they are sent to reception centers throughout the country. Some of these reception centers have grown to substantial size and now house a more stable population, with continuous input of new arrivals. In these conditions, local transmission can occur with a possible risk for epidemics: 2 of the 5 patients reported here were long-term residents in Italy, and they denied recent travel to Africa, so they probably acquired the infection while being housed in the same facilities as the newly arrived refugees. Although it is possible that they denied recent travel for fear of legal consequences, they are unlikely to have had the opportunity to travel out of Europe for economic reasons.

We did not find any louse on the body or in the clothing of these patients. However, we identified B. recurrentis by gene sequencing, and the dynamic of transmission we postulate in our cases fits more closely the model of louse transmission (overcrowding, poor hygienic conditions, migration) than that of tick transmission (1,3,4). Lice are relatively short-lived and remain infected throughout their lives but cannot transmit borreliae to their progeny. They do not inject borreliae directly while feeding (infection takes place when they are crushed on skin) (1): infected lice can survive on uninfected persons but, when moved to other persons, give rise to infection. Thus, identifying a direct chain of transmission is often challenging. The presence of lice has been reported as a growing problem in western Europe homeless persons with no history of travel, threatening an alarming scenario (4,5).

All 5 patients reported here sought care at one of the EDs in Turn for fever associated with other nonspecific symptoms; all 5 diagnoses were made as occasional observations of spirochetes on thin and thick blood smears conducted to search for malaria parasites. These 5 patients might represent a minority of persons who are actually affected by relapsing fever. In fact, in many instances, persons seen at an ED for fever, especially persons without a history of recent travel to malaria-endemic countries, would not be investigated for malaria and would probably be treated empirically with antimicrobial drugs, leading to resolution of symptoms without further investigations.

Two of the patients we report had symptoms suggestive of a JHR. JHR is an acute, febrile reaction, potentially fatal, occurring shortly after starting antimicrobial drugs, probably attributable to the release of cytokines associated with clearance of borreliae from blood (2,6). A higher frequency of JHR has been reported in the literature, up to 80% (6,7), with some differences depending on the antimicrobial drug used (7,8). However, most observations were performed in LRF-endemic countries. These patients were all hospitalized and were receiving supportive treatment (intravenous rehydration and paracetamol, either intravenously or orally, to control headache, myalgia, and abdominal pain), which might have played a role in avoiding JHRs or in reducing its symptoms. Several studies have been conducted on possible preventive options to avoid the arousal of JHR, but results have not been consistent (9). Some clue of a possible action of paracetamol on the development of JHR has been reported (8).

Conclusions

In summary, we identified B. recurrentis infection in 5 patients in Italy who were refugees from East Africa; 2 of these patients had not traveled outside Italy for several years. Beginning in July 2015, several reports from countries in Europe have described relapsing fever in refugees from East Africa (10–13). In some of these cases, transmission might have occurred during transit through Italy (12). Our findings confirm the possibility of local transmission of LRF caused by B. recurrentis.

Biography

Dr. Lucchini is an infectious disease specialist at the Hospital for Infectious Diseases in Turin. Her primary research interests include sexually transmitted infections, HIV, and tropical diseases in travelers.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Lucchini A, Lipani F, Costa C, Scarvaglieri M, Balbiano R, Carosella S, et al. Louseborne relapsing fever among East African refugees, Italy, 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016 Feb [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2202.151768

References

- 1.Cutler SJ. Relapsing fever—a forgotten disease revealed. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:1115–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04598.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elbir H, Raoult D, Drancourt M. Relapsing fever borreliae in Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2013;89:288–92 and. 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0691 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryceson ADM, Parry EHO, Perine PL, Warrel DA, Vukotich D, Leithead CS. Louse-borne relapsing fever. Q J Med. 1970;39:129–70 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouqui P, Raoult D. Arthropod-borne diseases in Homeless. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1078:223–35. 10.1196/annals.1374.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badiaga S, Raoult D, Brouqui P. Preventing and controlling emerging and reemerging transmissible diseases in the homeless. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:1353–9. 10.3201/eid1409.080204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negussie Y, Remick DG, DeForge LE, Kunkel SL, Eynon A, Griffin GE. Detection of plasma tumor necrosis factor, interleukin 6, and 8 during the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction of relapsing fever. J Exp Med. 1992;175:1207–12. 10.1084/jem.175.5.1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrier G, Doherty T. Comparison of antibiotic regimens for treating louse-borne relapsing fever: a meta-analysis. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2011;105:483–90. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2011.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Butler T, Jones PK, Wallace CK. Borrelia recurrentis infection: single-dose antibiotic regimen and management of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction. J Infect Dis. 1978;137:573–7. 10.1093/infdis/137.5.573 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pound MW, May DB. Proposed mechanisms and preventative options of Jarisch-Herxheimer reactions. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2005;30:291–5. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2005.00631.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilting KR, Stienstra Y, Sinha B, Braks M, Cornish D, Grundmann H. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) in asylum-seekers from Eritrea, the Netherlands, July 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:21196. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.30.21196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldenberger D, Claas GJ, Bloch-Infanger C, Breidhardt T, Suter B, Martinez M, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) in an Eritrean refugee arriving in Switzerland, August 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:2–5. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES2015.20.32.21204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoch M, Wieser A, Löscher T, Margos G, Pümer F, Zühl J, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever (Borrelia recurrentis) diagnosed in 15 refugees from northeast Africa: epidemiology and preventive control measures, Bavaria, Germany, July to October 2015. Euro Surveill. 2015;20:30046. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.42.30046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cierrvo A, Mancini F, di Berenardo F, Giammarco A, Vitale G, Dones P, et al. Louse-borne relapsing fever in young migrants, Sicily, Italy, July–September 2015. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016;22:152–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]