Abstract

Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate (MGL) is a new stereoisomer of glycyrrhizic acid, which is clinically used as a hepatoprotective medicine with more potent effects and less side effects than glycyrrhizic acid. This study was designed to evaluate the protective effects and possible mechanism of MGL against concanavalin A (Con A)-induced autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatitis was induced by Con A in C57/6J mice with or without MGL administration; injury score and serum ALT were evaluated. The CD4+ T-cells were isolated from splenocytes and challenged with Con A after coculturing with MGL. The injury score was significantly improved in MGL-treated mice after Con A challenging for 12 and 24 hours compared with those merely challenged with Con A. Similar trends were observed in the serum levels of ALT and AST. The most interesting result was that MGL administration significantly decreased the frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells rather than CD4+CD25+CD69+ T-cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells, after Con A challenging 12 and 24 hours. Moreover, the serum ALT levels were markedly correlated with the frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ cells, but only weakly correlated with CD4+CD25+CD69+ cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. More importantly, MGL (5 mg/mL) almost completely eliminated the proliferation of the CD25−CD69+ subset in primary CD4+ T-cells after Con A challenge. Compared with merely Con A-challenged mice, those with MGL administration significantly demonstrated decreased NALP3, NLRP6, and caspase-3 expression, in which the NALP3 and caspase-3 downregulated in a dose-dependent manner. Our results indicate that MGL may have potential as a therapeutic agent in autoimmune hepatitis by ameliorating liver injury. Its molecular mechanism may be involved in inhibiting CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset proliferation and downregulating inflammasome expression in liver tissue.

Keywords: autoimmune hepatitis, drug therapy, concanavalin A, mouse, adaptive immunity, regulatory T-cell

Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is a progressive inflammatory liver disease associated with interface hepatitis on liver biopsy, raised plasma liver enzymes, the presence of autoantibodies, and regulatory T-cell (Treg) dysfunction.1,2 The clinical course is heterogeneous and is manifested by a fulminant or indolent process.3 AIH is a complex polygenic disease which remains a major clinical challenge, since its exact etiology is still unknown.4 Autoreactivity against some components of hepatocytes is critical in the pathogenesis of AIH; the molecular mechanisms resulting in breakdown of immune tolerance in this disease have not been fully clarified.4 Since Tregs (CD4+CD25+) play a major role in maintaining immunological self-tolerance5 and preventing a variety of autoimmune diseases, impairment of Tregs was considered a pivotal step in the pathogenesis of AIH.4,6,7

Corticosteroids, either administered alone or in combination with azathioprine, are the mainstay therapies of AIH, but most patients had a relapse after medicine withdrawal.8 Many patients eventually progress to end-stage liver disease.9 Furthermore, more than 10%–20% of AIH patients were refractory.10 Importantly, some serious side effects of those drugs also influence patient’s compliance to drug therapy such as immunosuppression, osteoporosis, and sodium retention.11,12 Until now, there have been hardly any drugs which can be used for patients with AIH who are unresponsive to standard therapy; other immunosuppressive agents are limited to several clinical studies that involve only small numbers of patients.13

Glycyrrhizic acid (GA), extracted from the roots of licorice plants, is a conjugate of two molecules, namely glucuronic acid and glycyrrhetinic acid.14 Worldwide, it has been reported for its anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, and it was broadly used as a liver-protection drug.14,15 Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate (MGL) is a magnesium salt of 18-α GA stereoisomer and possesses greater hepatic protection and anti-inflammatory activity than β-GA.16,17 Moreover, MGL is able to inhibit the ethanol-induced lipid peroxidation18 and prevent ischemia/reperfusion-induced liver injury19 and free fatty acid-induced hepatic lipotoxicity.20 However, the effects and mechanism of action of MGL in AIH treatment still need elucidation.

Although several other mice models were used for studying AIH for many years, the concanavalin A (Con A) model is still the most commonly used AIH model, because Con A mainly stimulated CD4+ T-cells, which play a major role in pathogenesis of AIH.4,7 Using a Con A-induced AIH model, we found that MGL may significantly ameliorate Con A-induced liver injury. MGL inhibited not only the proliferation of CD25+CD69+ subset but also the CD25−CD69+ subset of CD4+ T-cells. However, the most interesting result is that the frequency of CD25−CD69+ subset significantly correlated with serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels, instead of CD25+CD69+ subset of CD4+ T-cells. This data suggested that the CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset of Treg may play a more important role in Con A-induced liver injury, rather than the CD4+CD25+CD69+ subset.

Materials and methods

Animals and drugs

This study was undertaken with the approval of the Animal Experimental Ethical Committee of Beijing Ditan Hospital. Male C57/B6J mice, 6–8 weeks, were obtained from the Laboratory Animal Center of Health Science Center, Peking University. All mice were allowed to habituate to specific pathogen-free conditions (five mice per cage, 21°C±2°C, 12 hours light/dark cycle). The MGL structure has been described in a previous report17 and was supplied by Chia Tai-Tianqing Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., (Nanjing, People’s Republic of China). The purity of MGL was 99.3% (lot: 20140920). It was stored at room temperature and diluted with 0.9% saline 1 hour before administration.

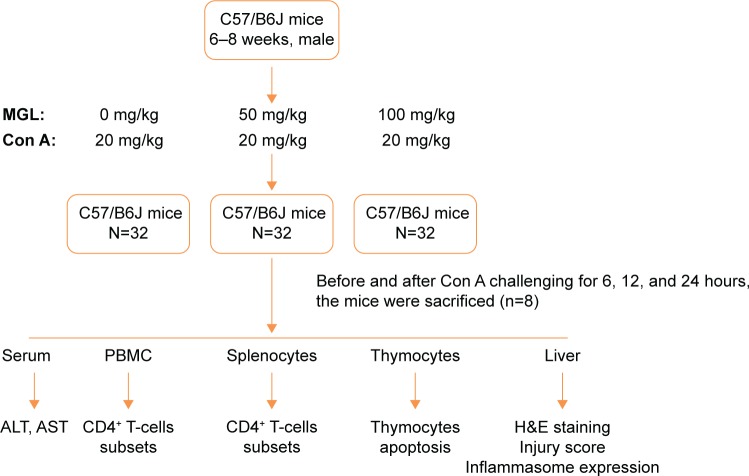

Protocols for Con A model

For preparing the Con A-induced liver injury mouse model, mice were challenged with 20 μg/g Con A (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) intravenous injection, diluted in sterile saline 6, 12, and 24 hours before they were killed. For MGL-treated mice, 50 or 100 mg/kg MGL (diluted with saline) were administrated (ip) before Con A challenging 2 hours. The control mice were administrated an equal volume of saline before they were killed. The mice were killed after Con A administration 6, 12, and 24 hours, and thymus, spleen, liver, and blood were collected for analysis (Figure 1). The specimens were removed and prepared for histomorphologic examination. ALT and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were determined using standard enzymatic methods.

Figure 1.

Study design (in vivo).

Abbreviations: MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; Con A, concanavalin A; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell.

Liver injury grading score

Livers of mice were dissected and partially fixed in formalin at the time of euthanasia. After paraffin embedding, sectioning, and H&E staining, the revised Knodell scoring system was used to evaluate degree of liver damage.21 In brief; 1, no inflammation or spotty necrosis; 2, piecemeal necrosis or confluent necrosis (less than 10%); 3, confluent necrosis (10%–50%); and 4, large area of confluent necrosis (more than 50%) with/without bridging necrosis. Injury scoring was performed in a blinded fashion.

Flow cytometry

After red blood cells were lysed with lysis buffer (eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), the remaining cells were stained with fluorescein-labeled monoclonal antibody of CD4 (allophycocyanin), CD8 (peridinin-chlorophyll protein), CD25 (phycoerythrin), and CD69 (Fluorescein isothiocyanat). Splenocytes were harvested after mice were killed. The percentage of CD25−CD69+ and other subsets in CD4+ T-cells was determined by flow cytometry.

The CD4+ T-cells were isolated from splenocytes for Con A challenging in vitro. The isolation method was based on manufacturer’s protocol (mouse CD4+ T Cell Isolation Kit; Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany) as described previously.22 After Con A (2.5 μg/mL) challenging and MGL (1 and 5 mg/mL) coculture for 0, 6, 12, and 24 hours, the CD4+ T-cells were harvested. The surface marker on CD4+ T-cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

For detecting apoptosis in thymocytes, the thymus glands were collected and thymocytes suspension was prepared. The thymocytes were stained with CD4 and CD8 monoclonal antibody, and Annexin V-FITC/7AAD kit (BD Pharmingen, San Jose, CA, USA), before the flow cytometry analysis.

Western blot

The protein extracts of liver tissue were quantified by the Bradford method. About 25 μg of each liver sample was pooled to normalize 100 μg of total protein for each mouse. The protein extracts were separated on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. Then, the proteins were probed with monoclonal anti-NALP3 (Abcam®, Cambridge, UK; 1:1,000), anti-NLRP6 (Abcam®; 1:1,000), and anti-caspase-3 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA; 1:1,000), followed by second conjugated immunoglobulins (Abcam®). The enhanced chemiluminescence methodology was used to perform final detection.

Statistical analyses

The data are presented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed by Student’s t-test or ANOVA. GraphPad Prism 5.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA) was used to perform data analysis. Statistical significance is defined as P<0.05.

Results

MGL ameliorated Con A-induced liver injury

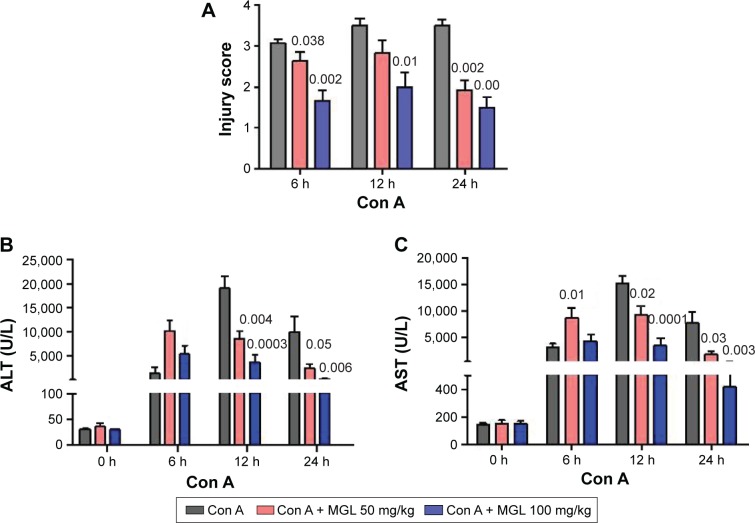

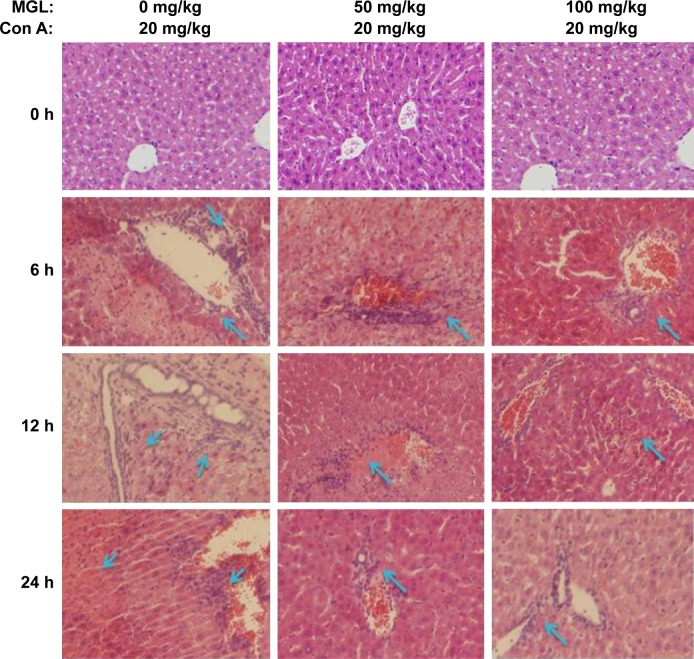

To observe the effect of MGL on Con A-induced liver injury, we first evaluated the difference in liver function tests among Con A and Con A + MGL administered mice. The results showed that MGL administration significantly inhibited the increase in levels of Con A-induced ALT and AST (Figure 2A and B). Compared with those of Con A-challenged mice (12 hours: 19,027±5,842 U/L; 24 hours: 10,008±8,265 U/L), the ALT levels of MGL (50 and 100 mg/kg)-administered mice were significantly decreased after Con A challenging for 12 hours (8,598±3,739 and 3,709±3,950 U/L, respectively), and 24 hours (2,993±1,889 and 304.3±136.2 U/L, respectively). A similar variation trend was also observed in AST level (Figure 2B). As expected, the liver injury score was also improved in MGL-treated mice after Con A challenging for 6, 12, and 24 hours compared with those of merely Con A-challenged mice (Figure 2C). H&E staining showed that Con A-challenged mice had interface hepatitis with piecemeal necrosis and lymphocyte spillover across the limiting plate (Figure 3). MGL administration markedly improved hepatocyte necrotic injury and reduced number of infiltrating inflammatory cells in the necrotic area (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Liver function tests and injury scoring.

Notes: (A) Injury score of liver injury. (B) Serum ALT levels. (C) Serum AST levels. The data on the graphs indicate P values (treated group vs control group).

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Con A, concanavalin A; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate.

Figure 3.

H&E staining of liver tissue.

Notes: MGL administration significantly improved liver injury compared with merely challenging with Con A. The blue arrow indicates the infiltrating inflammatory cells in necrotic area (200×).

Abbreviations: Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin. subsets and ALT levels before and after Con A challenging

CD25−CD69+ rather than CD25+CD69+ subset correlated with ALT levels

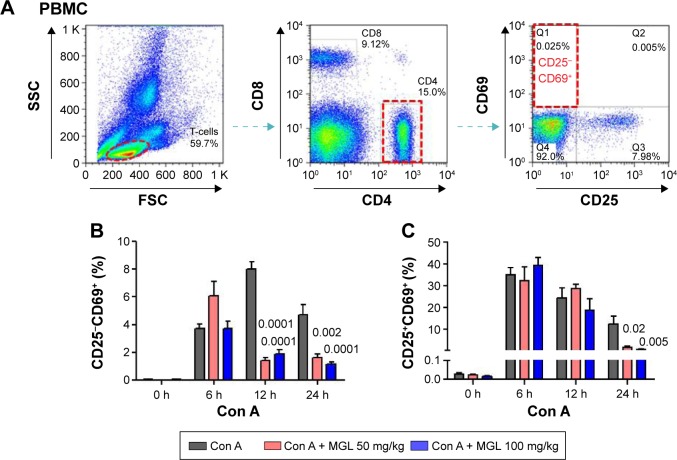

Since Con A-induced hepatocyte injury is dependent on CD4+ T-cell activation and subsets proliferation, we first analyzed the correlativity between subset of CD4+ T-cells and ALT levels in Con A-challenged mice. An important result is that the percentages of CD4+CD25−CD69+ subsets (r=0.721, P<0.0001) rather than CD4+CD25+CD69+ subsets (r=0.203, P=0.069) in peripheral blood mononuclear cells were significantly correlated with serum ALT levels in Con A-challenged mice (Table 1). However, this marked correlativity was not seen in CD4+ T-cells subsets in spleen. More importantly, MGL treatment significantly inhibited CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset proliferation after Con A challenge for 12 and 24 hours and weakly decreased the frequency of CD4+CD25+CD69+ T-cells in peripheral blood mononuclear cells after Con A challenge for 24 hours (Figure 4A and B).

Table 1.

The relationship between percentage of CD4+ T-cells subsets and ALT levels before and after Con Achallenging

| CD4+ T-cells subset | r | P-value |

|---|---|---|

| CD25−CD69+ | 0.721 | <0.0001 |

| CD25+CD69+ | 0.402 | 0.0002 |

| CD25+CD69− | 0.203 | 0.069 |

| CD25−CD69− | −0.477 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: ALT, alanine aminotransferase; Con A, concanavalin A.

Figure 4.

The subsets of CD4+ T-cells in PBMCs.

Notes: (A) Shows the frequency analysis of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells, representing results from control mice. (B) The frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells in PBMCs, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. (C) The frequency of CD4+CD25+CD69+ T-cells in PBMCs, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. The data on the graphs indicate P values (treated group vs control group).

Abbreviations: Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter.

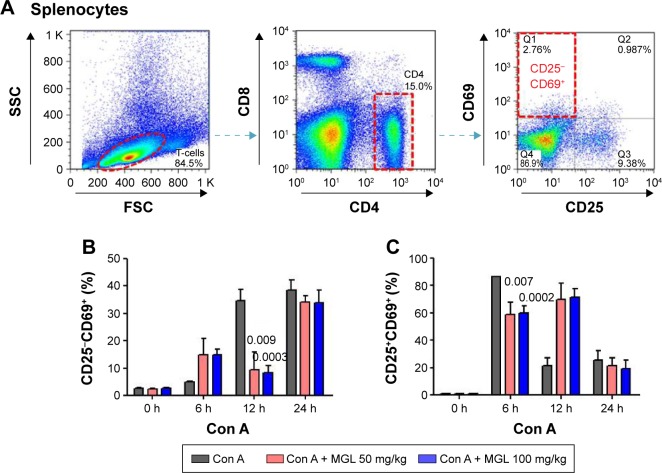

We also analyzed the subset variation of CD4+ T-cells in splenocytes after Con A challenge and/or MGL administration. As seen from Figure 5, cell proliferation in the CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset and the CD4+CD25+CD69+ subset in MGL-treated mice were partly inhibited after Con A challenge for 12 and 24 hours, respectively (Figure 5A and B).

Figure 5.

The subsets of CD4+ T-cells in splenocytes.

Notes: (A) Shows the frequency analysis of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells, representing results from control mice. (B) The frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells in splenocytes, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. (C) The frequency of CD4+CD25+CD69+ T-cells in splenocytes, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. The data on the graphs indicate P values (treated group vs control group).

Abbreviations: Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter.

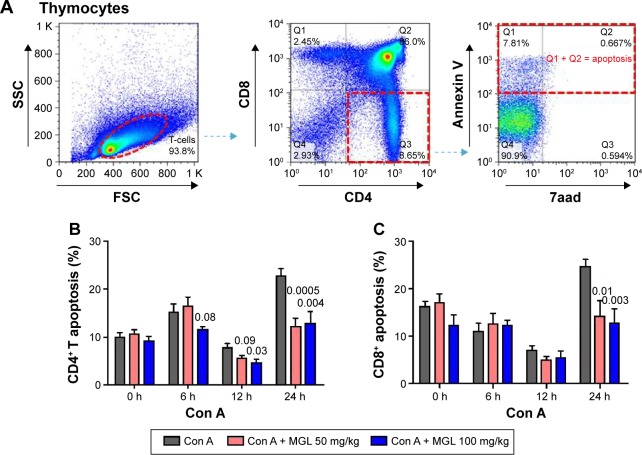

MGL partly inhibited CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in thymus

Classical Treg cells comprise two main groups: naturally arising in thymus and some peripherally induced. We next studied CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell apoptosis in thymus after Con A challenging and MGL administration. As expected, Con A challenging partly increased activation-induced thymocytes apoptosis. The results demonstrated that MGL significantly inhibited CD4+ T-cell apoptosis after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours (P<0.05) (Figure 6A). Furthermore, it seems that MGL also partly inhibited CD8+ T-cell apoptosis after Con A challenge for 24 hours (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

The apoptosis of T-cell subsets in thymocytes.

Notes: (A) Shows the analyzing method of CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in thymus. (B) CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in thymocytes, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. (C) CD8+ T-cell apoptosis in thymocytes, before and after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. The data on the graphs indicate P values (treated group vs control group).

Abbreviations: Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter.

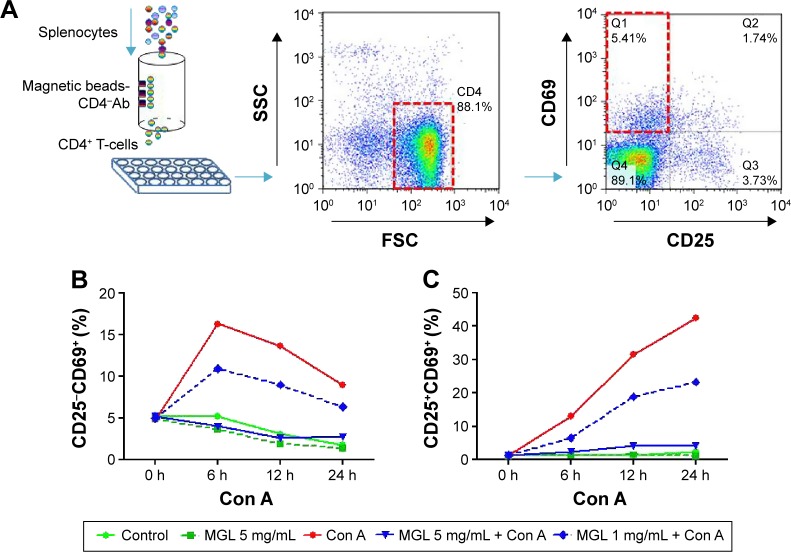

MGL directly inhibited subsets of CD4+ T-cell proliferation in vitro

To exclude the indirect role of MGL on proliferation of cells in the CD4+ T-cell subset after Con A challenge in vivo, we tested whether MGL could directly inhibit Con A-induced subset proliferation of CD4+ T-cells in vitro. We first isolated CD4+ T-cells from splenocytes and cocultured them with MGL (1 and 5 mg/mL, respectively) (Figure 7A). The results demonstrated that 5 mg/mL MGL almost completely eliminated proliferation of the CD25−CD69+ and CD25+CD69+ CD4+ T-cell subsets (Figure 7B and C). Similarly, the 1 mg/mL MGL significantly inhibited the proliferation of cells in the CD25−CD69+ and CD25+CD69+ subsets.

Figure 7.

The proliferation of cells in the CD4+ T-cell subset before and after MGL administration and/or Con A challenging.

Notes: The upper part of figure shows the study design in vitro. (A) The CD4+ T-cells were isolated from splenocytes using a specific CD4+ T-cells isolation kit and were then cultured in plates. (B) Con A challenging significantly increased the CD25−CD69+ subset of CD4+ T-cells, but the 5 mg/mL MGL almost completely eliminated proliferation of the CD25−CD69+ subset of cells after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. (C) Con A challenging significantly increased the CD25+CD69+ subset of CD4+ T-cells, but the 5 mg/mL MGL almost completely eliminated proliferation of the CD25+CD69+ subset of cells after Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours. The data on the graphs indicate P values (treated group vs control group).

Abbreviations: Ab, antibody; Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; SSC, side scatter; FSC, forward scatter.

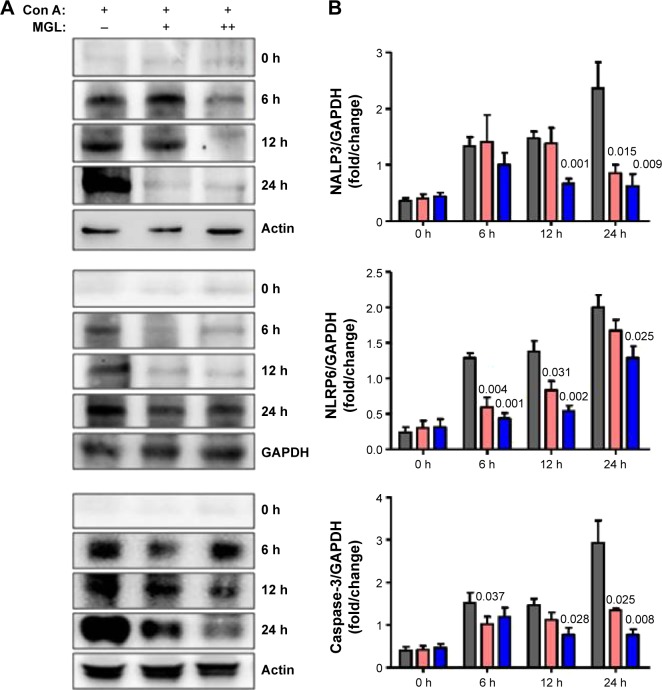

Downregulation of inflammasome expression related with improving liver injury

Activation of inflammasome is a main step in the process of inflammation and plays a pivotal role in hepatocytes injury.23 Based on recent reports, isoliquiritigenin (a derivative of GA) is a potent inhibitor of NALP3 inflammasome activation.24 Consequently, we examined the expression of the main components of inflammasome, ie, NALP3, NLRP6, and caspase-3, in liver tissue. Since inflammasomes are innate immune system receptors and are implicated in the process of inflammation, we hypothesized that inhibition of inflammasome activation by MGL may be related with improving liver injury. Indeed, NALP3, NLRP6, and caspase-3 were significantly downregulated in MGL-treated mice compared with those that were merely Con A-challenged, in which the NALP3 and caspase-3 were downregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

The inflammasome expression in liver tissue.

Notes: After Con A challenge for 6, 12, and 24 hours, the NALP3, NLRP6, and caspase-3 expression increased. (A) Shows the results of the Western blotting analysis, and (B) shows the plots of pixel intensity. For simplicity, representative blots of actin and GAPDH are shown. MGL administration significantly downregulated inflammasome expression, in which caspase-3 decreased in a dose-dependent manner.

Abbreviations: Con A, concanavalin A; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate.

Discussion

GA has been used as a liver-protection drug for several decades. Its new derivative, MGL was also used as a liver-protection drug in recent years. However, its effects on autoimmune liver injury and its potential mechanism of action still need to be elucidated. Our present results indicated that 1) MGL significantly improved the Con A-induced liver injury and 2) the mechanism may be related with MGL, which directly inhibits Con A-induced CD4+ T-cells proliferation and subsets differentiation.

Immunization of C57BL/6 mice with liver autoantigens (CYP2D6 or IL-4R) and Con A-induced disturbance of liver immune tolerance, leading to hepatitis, are still the most representative model of human AIH.25 The mechanism of Con A-induced breakdown of liver immune homeostasis has not been fully clarified. A numerical and functional defect in CD4+CD25+ Treg cells is regarded as playing a major role.4,6 In our present study, we found that the frequency of CD25−CD69+ rather than CD25+CD69+ subset of CD4+ T-cells was more significantly correlated with serum ALT levels in Con A-challenged mice. This result suggested that the CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset could also play an important role in autoimmune liver injury although this subset makes up only a relatively small proportion in total CD4+ Treg cells.

The CD25−CD69+ T-cell subset is a new kind of CD4+ Tregs and was first described by Han et al.26 They found that the new subset of Treg cells possessed distinct characteristics: 1) negative expression of Foxp3, 2) no secretion of IL-10, and 3) suppressing CD4+ T-cell proliferation in a cell–cell contact manner. However, its exact function still needs to be clarified.23 Recently, Zhu et al,27 reported that increased CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients are significantly correlated with invasion and tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage;28 similar results were also observed in leukemia patients. After receiving treatment, the incidence of relapse in patients with a high percentage of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells was significantly higher than that of patients with a low percentage of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells.29 Moreover, administration of CD25− T-cells could have induced recipient mice immune tolerance and increased long-term graft survival.30 Other results showed that a low percentage of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells is associated with an increased risk of acute graft-versus-host disease.31 These data suggested that the increase in frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells may lead to deterioration of the disturbance of immune homeostasis, although the exact molecular mechanism still needs to be elucidated. Based on our present data, MGL appears to enhance activation of both Treg populations at 6 hours (for CD25− cells) and 12 hours (for CD25+ cells). Two factors may be related with this apparent stimulation of cells. First, the niche of each Treg cell in blood and spleen are different. Second, the cytokine levels in spleen tissue and blood are also different.

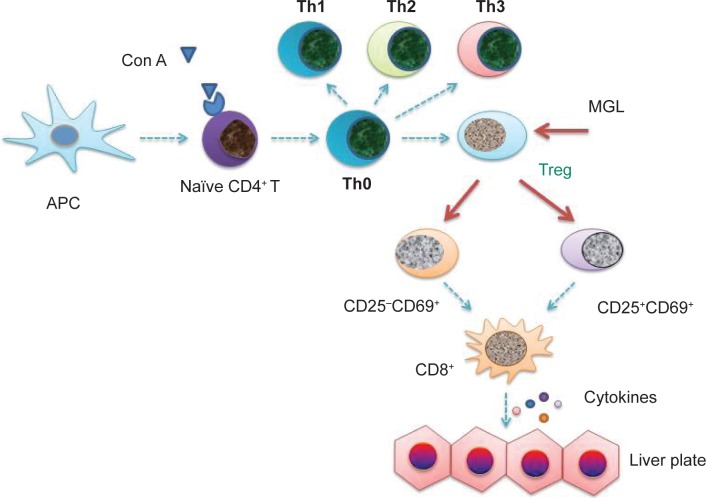

The CD4+CD25− subset is only ten-fold less potent than the CD4+CD25+ subset in immune tolerant mice, but it may be amplified in “tolerized” status.32 After receiving antigenic stimulation, moreover, the proliferating ability of CD4+CD25− T-cells was greater than CD4+CD25+ T-cells.33 These results are consistent with our present data. After Con A challenge for 24 hours, the frequency of CD4+CD25−CD69+ T-cells was raised up to nearly 40% of CD4+ T-cells, although this only made up less than 5% of the total primary CD4+ T-cells (Figure 5A). Other results as well as our present data suggested that nontraditional CD4+CD25−CD69+ Treg cells may play an important role in Con A-induced liver injury. Inhibiting CD4+CD25−CD69+ subset proliferation may be an important target of MGL for improving Con A-induced liver injury (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

The possible target in the pathogensis of autoimmune hepatitis.

Notes: The blue arrow indicates that the possible molecular mechanism of pathogenesis of autoimmune hepatitis. The red arrows indicate the possible targets of MGL’s proliferation inhibiting-capacity of the regulatory T-cell subsets. Based on these data, MGL inhibiting the expression of inflammasome may be a downstream event in CD4+ T-cell subsets regulation.

Abbreviations: APC, antigen presenting cell; MGL, magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate; Con A, concanavalin A; Treg, T regulator cell.

Since CD4+ T-cell proliferation was a marker of Con A-induced AIH, we speculated that some peripheral CD4+ T-cells may come from the thymus during Con A challenging. However, the present data showed that Con A induced CD4+ T-cell apoptosis, rather than proliferation, in the thymus. Furthermore, MGL partly inhibited CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in the thymus. This data indicated that effects of MGL on subset proliferation of peripheral CD4+ T-cell may be partly related with deceasing of CD4+ T-cell apoptosis in the thymus. Failing to further examine the subsets of CD4+ T-cells is one limitation of our present work.

Based on our present results, MGL improving Con A-induced liver injury also may be partly related with down-regulation of inflammasome expression and inhibiting apoptosis of thymocytes. Since Con A directly induced CD4+ T-cell proliferation, the downregulation of inflammasome expression should be a downstream event in the process of liver injury. However, our present study failed to perform the cytokine test, chemokine test, and RNAseq analysis. This is one of the major limitations in our present work. Consequently, the speculation still needs to be confirmed in future investigations.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Number 81271901); Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Number 7152073); Science Foundation of Capital Medicine Development (Number 2014-2-2171); and Capital Foundation for Clinical Characteristic Applied Research Projects (Number Z141107002514132) to Professor Wei and partly supported by Collaborative Innovation Center of Infectious Diseases (PXM 2015_014226_000058). The authors would like to acknowledge Yu Hao for assistance with flow cytometry procedures, and Drs Junyan Han, Youluan Zhu, and Qi Wang for helpful comments and discussion.

Footnotes

Author contributions

HW designed experiments and wrote the manuscript. QY, JW prepared the mice model. QY, JW, RL performed flow cytometry analysis. ZW, YL, YZ performed serum test and immunohistochemistry staining. XH, YH, WX analyzed cytometry data and statistical analysis. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Liberal R, Grant CR, Longhi MS, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Diagnostic criteria of autoimmune hepatitis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(4–5):435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen J, Eslick GD, Weltman M. Systematic review with meta-analysis: clinical manifestations and management of autoimmune hepatitis in the elderly. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39(2):117–124. doi: 10.1111/apt.12563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Floreani A, Liberal R, Vergani D, Mieli-Vergani G. Autoimmune hepatitis: contrasts and comparisons in children and adults – a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2013;46:7–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heneghan MA, Yeoman AD, Verma S, Smith AD, Longhi MS. Autoimmune hepatitis. Lancet. 2013;382(9902):1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62163-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyara M, Ito Y, Sakaguchi S. TREG-cell therapies for autoimmune rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014;10(9):543–551. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Mitry RR, et al. Effect of CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T-cells on CD8 T-cell function in patients with autoimmune hepatitis. J Autoimmun. 2005;25(1):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Longhi MS, Ma Y, Bogdanos DP, Cheeseman P, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D. Impairment of CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T-cells in autoimmune liver disease. J Hepatol. 2004;41(1):31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Czaja AJ. Current and prospective pharmacotherapy for autoimmune hepatitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2014;15(12):1715–1736. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2014.931938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carbone M, Neuberger JM. Autoimmune liver disease, autoimmunity and liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):210–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chatrath H, Allen L, Boyer TD. Use of sirolimus in the treatment of refractory autoimmune hepatitis. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1128–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshizawa K, Matsumoto A, Ichijo T, et al. Long-term outcome of Japanese patients with type 1 autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2012;56(2):668–676. doi: 10.1002/hep.25658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jothimani D, Cramp ME, Mitchell JD, Cross TJ. Treatment of autoimmune hepatitis: a review of current and evolving therapies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(4):619–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06579.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fallatah HI, Akbar HO. Mycophenolate mofetil as a rescue therapy for autoimmune hepatitis patients who are not responsive to standard therapy. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;5(4):517–522. doi: 10.1586/egh.11.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ming LJ, Yin AC. Therapeutic effects of glycyrrhizic acid. Nat Prod Commun. 2013;8(3):415–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Rossum TG, Vulto AG, de Man RA, Brouwer JT, Schalm SW. Review article: glycyrrhizin as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12(3):199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He Y, Zeng F, Liu Q, et al. Protective effect of magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate on ethanol-induced testicular injuries in mice. J Biomed Res. 2010;24(2):153–160. doi: 10.1016/S1674-8301(10)60024-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun L, Shen J, Pang X, Lu L, Mao Y, Zeng M. Phase I safety and pharmacokinetic study of magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate after single and multiple intravenous doses in Chinese healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(6):767–773. doi: 10.1177/0091270007299757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xie C, Li X, Wu J, et al. Anti-inflammatory activity of magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate through inhibition of phospholipase A2/arachidonic acid pathway. Inflammation. 2015;38(4):1639–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10753-015-0140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang X, Qin J, Lu S. Magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate protects hepatic L02 cells from ischemia/reperfusion induced injury. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7(8):4755–4764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheng Y, Zhang J, Shang J, Zhang L. Prevention of free fatty acid-induced hepatic lipotoxicity in HepG2 cells by magnesium isoglycyrrhizinate in vitro. Pharmacology. 2009;84(3):183–190. doi: 10.1159/000235873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knodell RG, Ishak KG, Black WC, et al. Formulation and application of a numerical scoring system for assessing histological activity in asymptomatic chronic active hepatitis. Hepatology. 1981;1(5):431–435. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840010511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matheu MP, Cahalan MD. Isolation of CD4+ T cells from mouse lymph nodes using Miltenyi MACS purification. J Vis Exp. 2007;(9):409. doi: 10.3791/409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lerch MM, Conwell DL, Mayerle J. The anti-inflammasome effect of lactate and the lactate GPR81-receptor in pancreatic and liver inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1602–1605. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Honda H, Nagai Y, Matsunaga T, et al. Isoliquiritigenin is a potent inhibitor of NLRP3 inflammasome activation and diet-induced adipose tissue inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2014;96(6):1087–1100. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3A0114-005RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yüksel M, Laukens D, Heindryckx F, et al. Hepatitis mouse models: from acute-to-chronic autoimmune hepatitis. Int J Exp Pathol. 2014;95(5):309–320. doi: 10.1111/iep.12090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han Y, Guo Q, Zhang M, Chen Z, Cao X. CD69+ CD4+ CD25− T cells, a new subset of regulatory T cells, suppress T-cell proliferation through membrane-bound TGF-beta 1. J Immunol. 2009;182(1):111–120. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhu J, Feng A, Sun J, et al. Increased CD4(+) CD69(+) CD25(−) T cells in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma are associated with tumor progression. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(10):1519–1526. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06765.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu D, Wang FS. Are non-traditional CD4(+) CD69(+) CD25(−) regulatory T cells involved in disease progression of human hepatocellular carcinoma? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;26(10):1469–1470. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2011.06845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao XS, Wang XH, Zhao XY, et al. Non-traditional CD4+CD25−CD69+ regulatory T cells are correlated to leukemia relapse after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Transl Med. 2014;12:187. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Degauque N, Lair D, Braudeau C, et al. Development of CD25− regulatory T cells following heart transplantation: evidence for transfer of long-term survival. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37(1):147–156. doi: 10.1002/eji.200635879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lu SY, Huang XJ, Liu KY, Liu DH, Xu LP. High frequency of CD4+ CD25− CD69+ T cells is correlated with a low risk of acute graft-versus-host disease in allotransplants. Clin Transplant. 2012;26(2):E158–E167. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2012.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Graca L, Thompson S, Lin CY, Adams E, Cobbold SP, Waldmann H. Both CD4(+)CD25(+) and CD4(+)CD25(−) regulatory cells mediate dominant transplantation tolerance. J Immunol. 2002;168(11):5558–5565. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall BM, Robinson CM, Plain KM, et al. Studies on naïve CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibition of naïve CD4+CD25− T cells in mixed lymphocyte cultures. Transpl Immunol. 2008;18(4):291–301. doi: 10.1016/j.trim.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]