Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the aqueous humor bioavailability and clinical efficacy of bromfenac 0.09% vs nepafenac on the presence of cystoid macular edema (CME) after phacoemulsification.

Material and methods

A Phase II, double-blind, masked, active-controlled, multicenter, clinical trial of 139 subjects, randomized to either a bromfenac 0.09% ophthalmic solution (n=69) or nepafenac 0.1% (n=70). Subjects instilled a drop three times a day for a period of 30 days. Follow-up visits were on days 2, 7, 15, 30, and 60. Biomicroscopy, clinical ocular signs, and assessment of posterior segment were performed. The primary efficacy endpoints included the presence of CME evaluated by optical coherence tomography. Safety evaluation included intraocular pressure, transaminase enzymes, lissamine green, and fluorescein stain.

Results

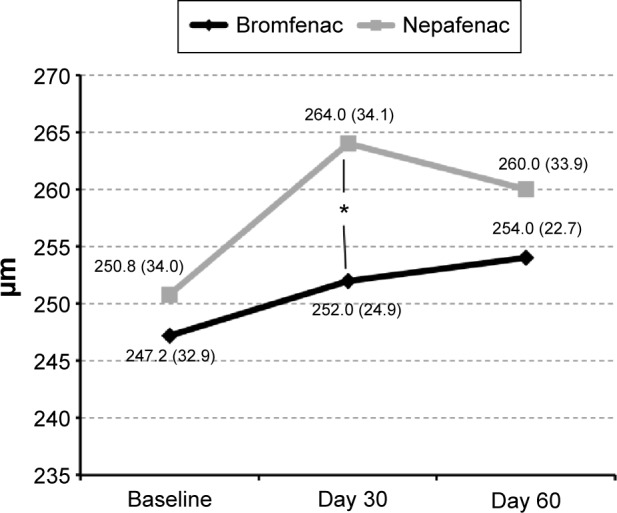

The demographic and efficacy variables were similar between groups at baseline. The presence of pain, photophobia, conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, cellularity, and corneal edema disappeared by day 30 in both groups. The central retinal thickness did not show significant changes after treatment when compared to baseline as follows: in the bromfenac group (247.2±32.9 vs 252.0±24.9 μm; P=0.958) and in nepafenac group (250.8±34 vs 264.0±34.1 μm; P=0.137), respectively. A statistically significant difference was observed between bromfenac and nepafenac group: (252.0±24.9 vs 264.0±34.1 μm; P=0.022), at day 30, respectively; even though there was no clinical relevance in the presentation of CME. There were no significant alterations in intraocular pressure, either lissamine green or fluorescein stains. The adverse events were not related to the interventions.

Conclusion

Bromfenac 0.09% ophthalmic solution showed similar clinical efficacy to reduce the presentation of CME after phacoemulsification compared to nepafenac 0.01%.

Keywords: bromfenac, ocular NSAID, cystoid macular edema, OCT

Introduction

Cystoid macular edema (CME) is a common cause of poor visual outcome after a complicated phacoemulsification. Usually CME is subclinical and its prevalence varies (5%–20%) depending on the diagnostic test.1–4 The pathophysiology involves an increase in vascular permeability due to prostaglandins’ elevated concentration as a consequence of a surgical inflammatory response by the rupture of cell membranes. However, the exact cause of CME is poorly understood.5

Management of inflammation is a mainstay after phacoemulsification.6 Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) block the prostaglandin response through inhibiting COX enzymes.7 The use of NSAIDs has been particularly associated with adverse events (AEs) in the ocular surface.8–10 Bromfenac is an NSAID with bromine atom at the C4 of the benzoyl ring position. Its chemical structure lengthens the duration of anti-inflammatory activity and enhances the absorption into the ocular tissues.11–14 Nepafenac is converted by the ocular tissues to amfenac, which is an active metabolite that inhibits COX enzymes.15,16 Even though both of them, bromfenac and nepafenac, have been shown to be effective, clinical studies have not yet concluded which one is better.6

Notwithstanding the fact that bromfenac ophthalmic solution has been evaluated in numerous clinical studies in Japan, USA, and other countries, in Mexico bromfenac is not available commercially and consequently no clinical data have been collected.

The purpose of the present study was to evaluate the aqueous humor bioavailability and clinical efficacy of bromfenac 0.09% vs nepafenac on the presentation of CME in Mexican patients after phacoemulsification.

Patients and methods

Study design

A parallel, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, multicenter clinical trial was designed to compare the efficacy of two ophthalmic solutions. The study was conducted at four research centers in Mexico. The sample size was calculated considering an alpha value of 0.05 and a difference of 1.4% in the absence of hyperemia between bromfenac and placebo.17 The protocol was approved by an ethics committee at each study center and the trial was conducted according to Good Clinical Practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients provided written informed consent before the initiation of study procedures. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov as NCT01591891.

Patient population

Inclusion criteria

We enrolled 139 volunteers (bromfenac group n=69; nepafenac group n=70). Patients of both sexes (aged >18 years) with a diagnosis of cataract according to the Lens Opacities Classification System III ≤ NC4, C4 and, P4 in one eye were eligible for enrollment. Eligible patients must have had a best-corrected visual acuity of 6/60 (20/200) Snellen score.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with autoimmune diseases, history of eye surgery within 3 months prior to baseline, ophthalmological diseases, those who wear contact lenses or used any topical NSAID or corticosteroid within 2 weeks before enrollment were excluded. The presence of a condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would have interfered with optimal participation in the study; or participation in any other clinical trial within 90 days of the screening visit were also criteria for exclusion.

Intervention

Patients were randomly allocated 1:1 to receive bromfenac 0.09% (Zebesten ofteno; Sophia Laboratories SA de CV, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico) or nepafenac 0.1% (Nevanac; Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) using a computer that generated a list of random numbers. The morning of the scheduled cataract surgery, a nurse was instructed to instill five drops into each patient’s eye in the hour before surgery. After surgery the subjects instilled one drop of study drug topically in the conjunctival sac of the eye three times daily for 30 days. Investigators were masked to the study medication. Because the active control bottle (Nevanac) was visibly different compared to the investigational bottle, a designee at each study site, other than the investigator, was responsible for dispensing the study treatment. Attempts were made to mask the subjects by removing commercial labeling, replacing it with identical investigational labels, and packaging in identical kit boxes.

Assessments

After surgery, Visit 0 (Day 0), patients were evaluated during six study visits: Visit 1 (Day 1±1), Visit 2 (Day 7±1), Visit 3 (Day 15±1), Visit 4 (Day 30±1) and, telephone follow-up Visit 5 (Day 60±1).

Efficacy

Clinical evaluation of ocular signs: pain, photophobia, conjunctival hyperemia, chemosis, cellularity, and corneal edema were evaluated at all visits. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) was performed on Day 0, 30 and, 60 using Cirrus HD-OCT spectral domain technology, (Carl Zeiss Meditec, AG, Jena, Germany).

The primary efficacy outcome was the absence of CME during spectral domain OCT determined for central retinal thickness (CRT) <275 μm, according to American Academy of Ophthalmology guidelines, after phacoemulsification. Secondary efficacy assessments included the decrement of ocular inflammation signs.

Safety

Safety was assessed in all patients who received at least one dose of bromfenac or nepafenac during all visits. The intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement was performed using a Goldmann tonometer. The safety range was IOP >8 and <21 mmHg. Fluorescein and Lissamine green staining was considered without clinical relevance if <5% of the ocular surface was stained. Transaminase enzymes were measured at 0 and 30 days. ALT and AST were considered altered if they had an increase of two times the upper-limit from baseline. Additional safety assessments included reports of serious AEs during all visits.

Laboratory analysis

Concentration of study drugs

The concentration of both drugs was determined for aqueous humor sample (0.15 mL) with a 30-gauge needle on a TB syringe after completion of the paracentesis. The paracentesis was performed after first incision during the phacoemulsification. Following the aqueous humor collection, samples were stored at −40°C prior to analysis. Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) was performed on a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (5 μm, 4.6×250 mm; Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a gradient solvent system (A =0.1% formic acid in water and B =0.1% formic acid in methanol) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. A photodiode array mass detector was used.

Transaminase enzymes were measured in serum. The levels were determined by kinetic assays in a mass spectrophotometer.

Statistical analysis

The means of CRT, IOP, age and, transaminase enzymes were analyzed using a paired T-test. Ocular signs, AEs, fluorescein and lissamine dyes’ results were summarized using proportions and were analyzed with the chi-square method. The concentration of both drugs and amfenac was summarized using mean and standard deviation.

In all analyses, a P-value of <0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS software (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) version 19.

Results

A total of 139 patients were enrolled in the study and completed all visits (bromfenac group n=69; nepafenac group n=70). Three sites in Mexico City included 105 patients and one site in Guadalajara, Jalisco included 34 patients. The treatment groups were comparable in regards to demographics and baseline characteristics (Table 1). The primary efficacy endpoints were similar between groups at baseline. There were no reported complications during phacoemulsification. After intervention time, the CRT did not show statistical changes – meaning CME was not present (Figure 1). There were no significant differences when comparing groups. Moreover, in both groups decreased presence of pain, chemosis, photophobia, flare, hyperemia, cellularity, and corneal edema was observed. The IOP did not increase from baseline (14.6±1.8 vs 14.2±1.8 mmHg) to final visit (14.1±1.7 vs 13.7±1.9 mmHg; P=0.650) in bromfenac and nepafenac group, respectively. The AEs were not related to the interventions. The mean peak aqueous concentration of nepafenac, amfenac, and bromfenac was 314.4±146.5, 110.2±109.0, and 207.5±152.3, respectively. There were no side effects reported after paracentesis.

Table 1.

Subject demographics and baseline characteristics

| Bromfenac

|

Nepafenac

|

P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n=69 | n=70 | ||

| Sex, N | |||

| Female/male | 41/28 | 39/31 | 0.658 |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean ± SD | 67.4±11.1 | 68.0±9.5 | 0.727 |

| IOP, mmHg | |||

| Mean ± SD | 14.0±1.8 | 14.2±1.8 | 0.618 |

| ALT, mg/dL | |||

| Mean ± SD | 22.8±11.4 | 23.6±14.0 | 0.703 |

| AST, mg/dL | |||

| Mean ± SD | 22.3±7.2 | 23.1±10.4 | 0.645 |

Note: Paired T-test.

Abbreviations: IOP, intraocular pressure; SD, standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Change in mean central retinal thickness after phacoemulsification (mean standard deviation).

Note: *P=0.022.

Discussion

Inflammatory response has the purpose to repair the damaged tissues and eliminate dead cells and detritus. However this response can generate abnormalities in contiguous tissues because the cells and biomarkers involved do not have a precise limit to their action. CME presentation after phacoemulsification comes from the inflammatory response in tissues around the lens and consequently to the posterior segment structures, all this is believed to be due to the increase in the prostaglandins’ synthesis.5,18–20 Although the exact pathophysiologic mechanism of CME remains unclear, this is one of the most common causes of poor visual outcome after cataract surgery.3,4 In addition, during the recovery period, the patient can experience pain and other symptoms as a consequence of inflammatory cascade. This pathologic frame has focused the therapeutic efforts of the ophthalmologic community on prophylactic treatment with NSAIDs and corticosteroids.6,21

NSAIDs have been used for more than 3 decades, approximately, for the treatment of pain. However, due to rates of adverse effects on the ocular surface, their use has been questioned.8–10

Bromfenac is an NSAID with a particular chemical structure, a bromine atom added to the 4′ position of the aromatic ring, which allows greater penetration and concentration in ocular tissues. This pharmacokinetic profile increases its potency to inhibit COX enzymes and modulate the inflammatory response.22,23

The effectiveness of bromfenac in the treatment of CME following cataract surgery has been reported in different populations but not in Mexican subjects.

The results of the present study demonstrate that bromfenac is as effective as nepafenac in preventing CME presentation. Similar to this study a trend toward increase in central retinal thickness in the nepafenac group was reported by Cable24 in a pilot study 6 weeks after surgery. However, the values were not enough to diagnose CME. The values are consistent with the findings in our study at 3 weeks. In addition, this result helps to confirm that eyes undergoing phacoemulsification experience an increase in retinal thicknesŝ5–12 μm between 4–6 weeks after surgery.

The concentration levels of bromfenac in aqueous humor were similar to the reports from most authors when compared to nepafenac concentration.14,17,21,25 In the current study, the levels of nepafenac were higher than bromfenac, however despite these results, the efficacy of bromfenac was better than nepafenac as a result of its greater potency. These results confirm that from the first day of instillation of bromfenac there is a potent effect inhibiting COX-2 and reducing the pain. Similar to other authors’ findings,26–28 the signs of ocular inflammation (hyperemia, flare, cellularity, and chemosis) disappeared at the end of the intervention, even though the bromfenac concentration seemed to be low when compared to nepafenac.

In spite of literature reports of adverse effects on the ocular surface epithelium due to the use of NSAIDs, our results did not show differences on lissamine green and fluorescein staining. In the bromfenac group the AEs were: CME after follow-up visits (n=1), posterior capsule rupture (n=1) during surgery, and viral conjunctivitis (n=1). In the nepafenac group, a patient presented with retinal vein occlusion and another with rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

This study adds scientific support to clinical practice about the utility of prophylactic therapy in patients undergoing phacoemulsification surgery. Further studies are necessary to measure inflammation biomarkers that could explain in more detail the pathophysiology of CME and the effect of NSAIDs on these molecules.

Conclusion

Bromfenac 0.09% ophthalmic solution is an effective NSAID in the treatment of ocular inflammatory signs and reducing the presentation of CME after 30 days of treatment compared to nepafenac. Moreover, it is safe for ocular surface and no changes on the corneal or conjunctival epithelium were clinically detected in Mexican patients after phacoemulsification.

Footnotes

Disclosure

Aldo A Oregon-Miranda and Arieh R Mercado-Sesma are employees of Laboratorios Sophia. This study was supported by Laboratorios Sophia SA de CV (Zapopan, México). The sponsor participated in the design of the study, data collection, data management, data analysis, interpretation of the data, and preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Drolsum L, Haaskjold E. Causes of decreased visual acuity after cataract extraction. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1995;21(1):59–63. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulkilik G, Kocabora S, Taskapili M, Engin G. Cystoid macular edema after phacoemulsification: risk factors and effect on visual acuity. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(6):699–703. doi: 10.3129/i06-062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mentes J, Ekagun T, Afrashi F, Kerci G. Incidence of cystoid macular edema after uncomplicated phacoemulsification. Ophthalmologica. 2003;217(6):408–412. doi: 10.1159/000073070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ursell PG, Spalton DJ, Whitcup SM, Nussenblatt RB. Cystoid macular edema after phacoemulsification: relationship to blood-aqueous barrier damage and visual acuity. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25(11):1492–1497. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(99)00196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flach AJ. The incidence, pathogenesis and treatment of cystoid macular edema following cataract surgery. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1998;96:557–634. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kessel L, Tendal B, Jorgensen KJ, et al. Post-cataract prevention of inflammation and macular edema by steroid and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory eye drops. A systematic review. Ophthalmology. 2014;121(10):1915–1924. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim AJ, Flach AJ, Jampol LM. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in ophthalmology. Major review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55:108–133. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guidera AC, Luchs JI, Udell IJ. Keratitis, ulceration, and perforation associated with topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(5):936–944. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(00)00538-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asai T, Nakagami T, Mochizuki M, Hata N, Tsuchiya T, Hotta Y. Three cases of corneal melting after instillation of a new nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Cornea. 2006;25(2):224–227. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000177835.93130.d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Congdon NG, Schein OD, von Kulajta P, et al. Corneal complications associated with topical ophthalmic use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(4):622–631. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)00801-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahuja M, Dhake AS, Sharma SK, Majumdar DK. Topical ocular delivery of NSAIDs. AAPS J. 2008;10(2):229–241. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9024-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baklayan GA, Muñoz M. The ocular distribution of 14C-labeled bromfenac ophthalmic solution 0.07% in a rabbit model. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:1717–1724. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S66638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baklayan GA, Patterson HM, Song CK, Gow JA, McNamara TR. 24-hour evaluation of the ocular distribution of 14C-labeled bromfenac following topical instillation into the eyes of New Zealand white rabbits. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2008;24(4):392–398. doi: 10.1089/jop.2007.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyake K, Ogawa T, Tajika T, Gow JA, McNamara TR. Ocular pharmacokinetics of a single dose of bromfenac sodium ophthalmic solution 0.1% in human aqueous humor. J Ocul Pharmacol Ther. 2008;24(6):573–578. doi: 10.1089/jop.2007.0132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gamache DA, Graff G, Brady MT, Spellman JM, Yanni JM. Nepafenac, a unique nonsteroidal prodrug with potential utility in the treatment of trauma-induced ocular inflammation: I. Assessment of anti-inflammatory efficacy. Inflammation. 2000;24(4):357–370. doi: 10.1023/a:1007049015148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walters T, Raizman M, Ernest P, Gayton J, Lehmann R. In vivo pharmacokinetics and in vitro pharmacodynamics of nepafenac, amfenac, ketorolac, and bromfenac. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33(9):1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donnenfeld ED, Holland EJ, Stewart RH, et al. Bromfenac ophthalmic solution 0.09% (Xibrom) for postoperative ocular pain and inflammation. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(9):1653–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Quinn CJ. Cystoid macular edema. Optom Clin. 1996;5(1):111–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tranos PG, Wickremasinghe SS, Stangos NT, et al. Macular edema. Surv Ophthalmol. 2004;49(5):470–490. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rotsos TG, Moschos MM. Cystoid macular edema. Clin Ophthalmol. 2008;2(4):919–930. doi: 10.2147/opth.s4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho H, Madu A. Etiology and treatment of the inflammatory causes of cystoid macular edema. J Inflamm Res. 2009;2:37–43. doi: 10.2147/jir.s5706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bucci FA, Jr, Waterbury LD. Comparison of ketorolac 0.4% and bromfenac 0.09% at trough dosing: aqueous drug absorption and prostaglandin E2 levels. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34(9):1509–1512. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cho H, Wolf KJ, Wolf EJ. Management of ocular inflammation and pain following cataract surgery: focus on bromfenac ophthalmic solution. Clin Ophthalmol. 2009;3:199–210. doi: 10.2147/opth.s4806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cable M. Comparison of bromfenac 0.09% QD to nepafenac 0.1% TID after cataract surgery: pilot evaluation of visual acuity, macular volume, and retinal thickness at a single site. Clin Ophthalmol. 2012;6:997–1004. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S32179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bucci FA, Jr, Waterbury LD. A randomized comparison of to-aqueous penetration of ketorolac 0.45%, bromfenac 0.09%, and nepafenac 0.1% in cataract patients undergoing phacoemulsification. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(12):2235–2239. doi: 10.1185/03007995.2011.626018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Silverstein SM, Jackson MA, Goldberg DF, Muñoz M. The efficacy of bromfenac ophthalmic solution 0.07% dosed once daily in achieving zero-to-trace anterior chamber cell severity following cataract surgery. Clin Ophthalmol. 2014;8:965–972. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S60292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rajpal RK, Ross B, Rajpal SD, Hoang K. Bromfenac ophthalmic solution for the treatment of postoperative ocular pain and inflammation: safety, efficacy, and patient adherence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:925–931. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S46667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Miyanaga M, Miyai T, Nejma R, et al. Effect of bromfenac ophthalmic solution on ocular inflammation following cataract surgery. Acta Ophthalmol. 2009;87(3):300–305. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-3768.2008.01433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]