Abstract

Objectives

Disruptions in sleep and dysregulation in circadian functioning may represent core abnormalities in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BP). However, it is not clear whether these dysfunctions are “state” or “trait” markers of BP. This report compared sleep and circadian phenotypes among three groups: offspring of bipolar parents diagnosed with (BP/OB; n=47) and without (non-BP/OB; n=386) BP at intake and offspring of matched control parents who did not have BP (controls; n=301). We also examined the association of baseline sleep parameters with subsequent development of BP among the non-BP/OB group.

Methods

Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study youth (ages 6-18) and their parents completed assessments every two years pertaining to child's sleep and circadian phenotypes and current psychopathology. Mixed-effects models examined differences on baseline sleep and circadian variables among the three groups.

Results

BP/OB offspring who were in a mood episode differed significantly on sleep parameters from the non-BP/OB and the offspring of controls, such as having inadequate sleep. Mixed logistic regression procedures showed that baseline sleep and circadian variables, such as frequent waking during the night, significantly predicted the development of BP among non-BP/OB over longitudinal follow-up.

Conclusions

While lifetime diagnostic status accounted for differences among the groups on sleep and circadian disturbances, psychopathology explained the differences even further. Additionally, sleep disturbance may be a prognostic indicator of the development of BP in high-risk youth. Future studies are required to further disentangle whether sleep and circadian disruption are state or trait features of BP.

Keywords: Mood, sleep, child, adolescent, age, moderation, psychopathology

Alterations in sleep and abnormalities in circadian functioning, 24-hour rhythms that characterize human physiology, biochemistry, and behavior,(1) have long been thought to be key components in the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder (BP).(2;3) Abnormalities in these two separate, but related, processes have been clearly demonstrated in adults and adolescents with BP during active mood episodes, and there is some evidence that sleep and circadian dysfunction are present during euthymia as well.(4-15) For example, some studies have shown that adolescents with bipolar disorder tend to have increased time to fall asleep, reduced sleep duration, reduced rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and impaired sleep efficiency as compared to healthy adolescents.(16-18) Moreover, prospective studies show associations between sleep disturbance and subsequent mood disruption or polarity switches in adults with BP, suggesting that changes in sleep may be causally related to mood dysregulation in this disorder.(19;20) Though evidence supports the presence of dysfunction in sleep and circadian rhythms during active mood episodes as well as euthymia, it is not clear whether these abnormalities are primarily “state” markers of mood state or a stable “trait” associated with BP.

The limited existing data suggest that sleep disturbances could be prodromal symptoms of BP,(21) those early symptoms that signal the onset of the disease. A number of recently published studies have shown that adolescent and young adult subjects at high-risk to develop BP are more likely to have at least some sleep and/or circadian dysfunction than controls, though these differences are not seen among all parameters.(22-26) Indeed, a relevant meta-analysis suggests that people at-risk for bipolar disorder have significantly lower relative amplitude of the sleep-wake cycle, lower variability in sleep efficiency, and greater variability in total sleep time as compared to controls (See(4) for a review). Given the sleep and circadian abnormalities among those diagnosed with, and at-risk for, BP, these trait-like characteristics may be biomarkers of BP since they are thought to represent an underlying chronobiological and genetic susceptibility to the disease.(27) However, we do not know whether or how sleep and circadian rhythms are related to the onset of BP, especially among those at genetic risk.

When conducting high-risk studies of children and adolescents, it is imperative to account for the fact that sleep and circadian functioning change over normal development, and to consider how such changes might be associated with onset of BP. Homeostatic sleep pressure accumulates more slowly during pubertal development,(28) making it harder for adolescents to fall asleep. In addition, developmental changes in the circadian system contribute to delayed circadian preference as adolescents age, which is usually seen as a shift to significantly later bed and wakeup times on weekends compared to weekdays.(29;30) As the school week resumes, this shift toward delayed sleep onset times often conflicts with early school start times, resulting in significant sleep deprivation in addition to circadian disruption.(31) These disruptions may potentially put adolescents at increased risk for the onset of mood symptoms.

The Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring Study (BIOS) provides an opportunity to address the above issues because it examined sleep and circadian phenotypes in a large sample of offspring of bipolar parent probands (OB) and offspring of demographically-matched community control parents, some of whom had non-BP psychopathology. At intake, 10.3% of the OB met criteria for a Bipolar Spectrum Disorder as compared to 0.8% of the offspring of community controls (OC).(32)

This report focuses on the evaluation of baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in the offspring cohorts. We hypothesized that, compared to the OC, the OB were more likely to have a tendency toward evening circadian phase preference and a larger discrepancy between weekend and weekday bedtimes and wake times. We also hypothesized that the OB had higher rates of sleep problems compared to OC. We hypothesized that these potential phenotypes were most prominent in the offspring of bipolar parents who met diagnostic criteria for BP (BP/OB), but were also present in higher rates in those that did not have BP (non-BP/OB). Because of the normative age-related changes in sleep and circadian rhythms over adolescence, we conducted exploratory analyses to determine if age moderated the impact of offspring group on sleep and circadian variables. Last, we hypothesized that baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in the non-BP/OB subjects were associated with future conversion to BP over subsequent longitudinal follow-up.

Methods

The methodology for BIOS is outlined below and has been described in detail in prior reports.(32)

Participants

Parents (Probands)

Parents with BP were recruited through advertisement (65%), adult BP studies (31%), outpatient clinics (1.3%), and random digit dialing (2.6%). Parents fulfilled Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Version-IV (DSM-IV)(33) criteria for BP I or II. Exclusion criteria included current or lifetime diagnoses of schizophrenia, mental retardation, mood disorders secondary to substance abuse, medical conditions, or medications, and living more than 200 miles away from Pittsburgh.

Community control parents consisted of healthy parents and parents with non-BP psychiatric disorders, grouped-matched by age, sex, and neighborhood, who were recruited using local population-based random dialing telephone surveys based on the demographic location of the parents with bipolar disorder. The exclusion criteria were the same as those for the parents with BP, with the additional requirements that neither of the biological parents could have BP and they could not have a first-degree relative with BP.

Offspring of BP and control parents

With the exception of children who were unable to participate (e.g., mental retardation), all offspring ages 6-18 from each family were included in the study. Offspring ages 2-5 that were recruited into the preschool offspring cohort of BIOS were eligible once they became age 6 and completed the full baseline assessment for 6-18 year olds.

Procedures

After Institutional Review Board approval and obtaining consent from parents and assent from children, parents and offspring were assessed for psychiatric disorders and other domains of interest. Assessments were performed for all subjects approximately every two years. Only methods and instruments directly related to this paper will be discussed.

Probands' DSM-IV psychiatric disorders were ascertained through the Structured Clinical Interview-DSM-IV (SCID)(34) plus several sections from the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL).(35) Parents were interviewed about their children and the children were directly interviewed for the presence of lifetime non-mood psychiatric disorders using the K-SADS-PL (the SCID was used for diagnosis of non-mood psychiatric disorders among offspring aged 18 or older). To evaluate the severity of each mood symptom, as well as mood disorder diagnosis, the K-SADS Mania Rating Scale (K-MRS) and the depression section of the KSADS-P (K-SADS Depression Rating Scale; K-DRS)(36;37) were used. A diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (BP-NOS) was made using operationalized criteria from the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Youth (COBY) study: a distinct period of abnormally elevated, expansive, or irritable mood plus: (1) 2 DSM-IV manic symptoms (3 if the mood is irritability only) that were clearly associated with the onset of abnormal mood, (2) a clear change in functioning, (3) mood and symptom duration of a minimum of 4 hours within a 24-hour period for a day to be considered meeting the diagnostic threshold, and (4) a minimum of 4 days (not necessarily consecutive) meeting the mood, symptom, duration, and functional change criteria over the subject's lifetime, which could be two 2-day episodes, four 1-day episodes,or another variation (see (38;39) for further details).

Bachelors- or masters-level interviewers completed all assessments after achieving ≥80% agreement with a certified rater. The overall SCID and KSADS kappa statistics for psychiatric disorders were ≥0.8. To ensure blindness to parental diagnoses, interviewers who assessed parental psychopathology were different from the interviewers who assessed their offspring' psychopathology. All data were presented to a child psychiatrist for diagnostic confirmation, who was blinded to the psychiatric status of the parents. When necessary, subjects' medical and psychiatric records were obtained and reviewed by their respective interviewers.

The Petersen Pubertal Developmental Scale (PDS)(40) and respective Tanner stages(41;42) were used to evaluate pubertal development. Socio-economic status (SES) was ascertained using the Hollingshead scale.(43) Sleep and circadian phenotypes were assessed using the School Sleep Habits Survey (SSHS).(44) The SSHS asks about the usual sleeping patterns over the prior two weeks on school days and weekend days, including bedtime and wake times, time it takes to fall asleep, duration of sleep, and frequency of night time awakenings. It also has questions regarding daytime sleepiness, perceived sufficiency and quality of sleep, and circadian phase preference (Morningness/Eveningness (M/E), or chronotype). Using the SSHS, M/E was calculated by summing the scores of 10 questions pertaining to morning/evening tendency, such as “Is it easy for you to get up in the morning” and “How do you think your child will do in gym class at 7:00am?” M/E scores range from 10-43, with higher scores indicating greater morning tendency. The SSHS has demonstrated relatively high correlation with data obtained from sleep diaries and actigraphy, and it has been used in large scale community studies of children and adolescents across the world.(45-48)

Parents completed the SSHS about their offspring from ages 6-18, and the offspring completed the measure for themselves starting at age 8 up until age 18. As the SSHS was added to the assessment battery two years after the BIOS study started recruiting subjects (added in November 2003), we included data from all subjects at the assessment time point when the SSHS was completed for the first time. Given that parents may have completed the SSHS for the first time when their child was 6 years old, but the child may not have completed the SSHS for the first time until her or she was 8 years old, we included only the first SSHS assessments when both the child and parent completed the SSHS at the same time point (n=734 total). The SSHS was completed by a parent or caregiver and, separately, by a child at the same time point for 47 BP/OB, 386 non-BP/OB, and 301 OC. Demographic data were used from the time when the SSHS was first completed, and diagnostic information included all lifetime diagnoses up to that time point.

Statistical Analyses

The offspring were divided into three groups for comparison: Offspring of bipolar parents with a diagnosis of a BP (BP/OB; n=47), offspring of bipolar parents without BP (non-BP/OB; n=386), and offspring of community control parents (OC; n=301). Two community control offspring who met criteria for BP were excluded from the analyses. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 or SAS 9.4. Comparisons of demographic and clinical characteristics between the groups were evaluated using linear and generalized linear mixed models. Linear mixed models were used to compare the three groups on sleep and circadian variables that were continuous. Generalized linear mixed models were used to compare the three groups on the five dichotomously-answered questions that ascertained sleep quality. All models used a random intercept to account for the presence of within family correlations. In addition, generalized linear mixed models were performed comparing the three participant groups on whether or not the subject had an “Extreme Evening” circadian preference, defined as a M/E score of <10th percentile of the entire sample, as per procedures used in prior studies.(48) In the included sample, the 10th percentile of M/E score was 21 in the parent-reported data and 20 in the child-reported data, similar to a previous report of 21 as the 10th percentile M/E score among a sample of 1073 Italian youth ages 8-14 years.(48) Demographic and clinical variables that differed among the groups at a level p≤0.20 (including the presence/absence of non-BP psychiatric disorders in the parents) were included in each model selection as covariates. Pubertal Status was highly correlated with age (r=0.80, p<0.0001) and was found to be much less predictive of sleep outcomes than age, so this variable was not retained in any models. Child age was subsequently added as an interaction term in the analyses (where p≤0.1) to test whether child age moderated differences among the groups on sleep and circadian parameters. All pairwise tests were conducted at the 0.05 level after Tukey correction in linear models and Bonferroni correction in generalized linear models. Additionally, we calculated odds ratios and partial Eta squared effect sizes for these effects.

To examine the extent to which significant group differences in sleep and circadian factors were associated with existing Axis I diagnoses in the offspring, we performed exploratory analyses including lifetime history of Anxiety Disorders, ADHD, and DBDs as covariates. In addition, we examined whether significant group differences in sleep and circadian factors were associated with current mood symptomatology by subdividing the BP/OB group into those individuals experiencing a current mood episode at the time of the SSHS, and those who were euthymic. We then re-ran our analyses comparing the four groups on sleep and circadian parameters; these exploratory analyses were conducted when the primary model was significant.

To evaluate whether sleep or circadian factors were associated with future onset of BP in the offspring of BP parents, we included all non-BP/OB who had at least one follow-up assessment subsequent to the baseline SSHS assessment. We used mixed logistic regression procedures to determine which sleep and circadian variables significantly predicted conversion to BP among non-BP/OB. Models were analyzed using parent-reported data and, separately, child-reported data. First, univariate logistic regression models were used, with each of the sleep variables as predictors. Variables were retained when a model returned a p≤0.2. Then automated stepwise, forward, and backward logistic model selection procedures (0.2 entry level, 0.05 retention level) were conducted. Last, we conducted a manual backward selection mixed logistic regression using the subset of variables with p≤0.2 from the univariate models and/or were retained by the automated selection procedures with a retention level of 0.05. A retention level of 0.1 was also used, which yielded the exact same models.

Results

Sleep and Circadian Variables and Offspring Groups defined at Baseline SSHS Assessment

Tables 1, 2, and 3 show parent- and child-reported characteristics and outcomes for each offspring group, as well as p-values for omnibus tests and pairwise comparisons between the groups.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Variables of Offspring – All Subjects at Baseline.

| Variable | BP Offspring of BP Parents N = 47 | Non-BP offspring of BP Parents N = 386 | Offspring of Control Parents N = 301 | F Stat. | P value | BP/OB vs. non-BP/OB | BP/OB vs. Controls | Non-BP/OB vs. Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and Parental Factors | ||||||||

| Gender (% female) | 55.3 | 50.3 | 52.2 | 0.28 | 0.8 | |||

| Lives with both biological parents (%yes) | 31.9 | 50.8 | 67.8 | 9.06 | 0.0001 | 0.4 | 0.0002 | 0.0008 |

| Puberty (% Tanner stage 4 or 5) | 42.6 | 28.8 | 29.6 | 1.67 | 0.2 | |||

| Race (% White) | 76.6 | 82.6 | 78.7 | 0.43 | 0.7 | |||

| Age (years) - Mean (SD) | 11.7 (3.3) | 11.4 (3.6) | 11.0 (3.5) | 3.55 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.009 | 0.3 |

| Socioeconomic Status – Mean (SD) | 31.1 (13.1) | 34.2 (14.4) | 38.5 (13.6) | 6.73 | 0.001 | 0.2 | 0.002 | 0.004 |

| Non-BP Axis I d/o in Parent | 91.5 | 91.5 | 47.8 | 37.99 | <0.0001 | 0.9 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| Lifetime History of Diagnosis (%) | ||||||||

| Anxiety Disorder | 51.1 | 28.0 | 11.0 | 22.51 | <0.0001 | 0.002 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ADHD | 56.8 | 25.1 | 12.1 | 19.96 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| ODD | 40.9 | 12.0 | 7.7 | 14.07 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | 0.08 |

| Conduct Disorder | 13.6 | 2.9 | 2.4 | 6.18 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.6 |

| Mood Symptom Severity (Worst Week in past 2 months) – Mean (SD) | ||||||||

| K-MRS (minus sleep item) | 20.9 (9.3) | 3.1 (4.7) | 1.1 (2.1) | 424.12 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| K-DRS (minus sleep items) | 27.5 (9.7) | 15.6 (6.6) | 13.3 (4.6) | 109.90 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

Group comparisons were evaluated after adjustment for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction in generalized linear models and Tukey correction in linear models.

Abbreviations: BP/OB: BP offspring of BP Parents; non-BP/OB: non-BP offspring of BP parents; SD – standard deviation; ADHD – Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ODD – Oppositional Defiant Disorder; D/O – disorder; K-MRS – KSADS Mania Rating Scale; K-DRS – KSADS Depression Rating Scale

Table 2. Parent Report of Offspring – All Subjects at Baseline.

| Variable | BP Offspring of BP Parents N = 47 | Offspring of BP Parents N = 386 | Offspring of Control Parents N = 301 | F Stat. | Effect Size | P value | Group Comparisons* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP/OB vs. non-BP/OB | BP/OB vs. Controls | Non-BP/OB vs. Controls | |||||||

| Circadian Phase Preference | |||||||||

| Morningness-Eveningness Score | 26.2 (6.0) | 28.0 (5.7) | 29.3 (4.9) | 3.75 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.007 | 0.1 |

| Extreme Evening (% M/E ≤ 21) | 23.4 | 11.9 | 9.6 | 2.44 | ORs= 2.1, 2.9 | 0.09 | |||

| Sleep Bedtime/Wake Time – Mean Hour:Minute (SD)† | |||||||||

| Bed time - weeknights | 21:36 (0:59) | 21:43 (1:08) | 21:28 (1:01) | 3.80 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.9 | 0.02 |

| Wake up time - weeknights | 6:53 (1:05) | 6:56 (0:53) | 6:50 (0:51) | 1.82 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.2 | |||

| Bedtime – weekend nights | 23:15 (1:28) | 23:14 (1:36) | 22:52 (1:30) | 1.85 | (x0019E)2=0.006 | 0.2 | |||

| Wake up time - weekend nights | 9:21 (1:35) | 9:22 (1:42) | 9:08 (1:27) | 0.18 | (x0019E)2=0.0008 | 0.8 | |||

| Bed time change (weeknight to weekend) | 1:41 (1:08) | 1:31 (1:03) | 1:24 (1:01) | 0.17 | (x0019E)2=0.0004 | 0.8 | |||

| Wake time change (weeknight to weekend) | 2:28 (1:55) | 2:28 (1:49) | 2:17 (1:40) | 3.29 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.04 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.4 |

| Sleep Durations – Mean Hours:Minutes (SD) | |||||||||

| Time in bed at weeknights | 9:15 (1:27) | 9:13 (1:27) | 9:23 (1:36) | 0.51 | (x0019E)2=0.002 | 0.6 | |||

| Time in bed at weekend nights | 10:11 (1:39) | 10:03 (1:28) | 10:08 (1:27) | 0.64 | (x0019E)2=0.0008 | 0.5 | |||

| Sleep duration on weeknights | 8:29 (1:30) | 8:43 (1:27) | 8:56 (1:37) | 0.14 | (x0019E)2=0.001 | 0.9 | |||

| Sleep duration on weekend nights | 9:35 (1:38) | 9:38 (1:28) | 9:45 (1:24) | 1.87 | (x0019E)2=0.008 | 0.2 | |||

| Time to fall asleep (weeknight) | 0:45 (0:48) | 0:29 (0:34) | 0:25 (0:21) | 3.58 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.03 | 0.009 | 0.02 | 0.9 |

| Time to fall asleep (weekend night) | 0:35 (0:43) | 0:23 (0:25) | 0:22 (0:20) | 3.26 | (x0019E)2=0.01 | 0.04 | 0.004 | 0.02 | 0.6 |

| Sleep Problems | |||||||||

| Any Sleep Problems (% Yes) | 57.5 | 32.1 | 31.2 | 4.57 | ORs= 2.7, 2.1 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.04 | 0.2 |

| Frequent awakenings during the night | 27.9 | 9.3 | 9.4 | 3.65 | ORs= 3.1, 2.0 | 0.03 | 0.008 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Daytime sleepiness | 4.4 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 1.62 | ORs= 2.8, 6.3 | 0.2 | |||

| Too little/too much sleep | 40.4 | 23.7 | 19.7 | 2.89 | ORs= 2.4, 2.2 | 0.06 | |||

| Poor sleeper | 38.3 | 12.5 | 8.8 | 8.86 | ORs= 4.2, 4.4 | 0.0002 | <0.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.8 |

| Inadequate sleep | 38.3 | 24.0 | 19.4 | 4.63 | ORs= 2.3, 2.4 | 0.01 | 0.004 | 0.003 | 0.8 |

Group comparisons were evaluated after adjustment for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni in generalized linear models and Tukey in linear models.

Abbreviations: BP/OB – BP offspring of BP Parents; non-BP/OB – non-BP offspring of BP parents; SD – standard deviation; M/E – Morningness/Eveningness total score

Table 3. Parent report of baseline child sleep separated by mood episode.

| Variable | Comparison Accounting for Current Mood: 1. BP/OB with Mood Episode, 2. BP/OB without Mood Episode, 3. Non-BP/OB, 4. Control Offspring* | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F stat. | P value | 1 vs. 2 | 1 vs. 3 | 1 vs. 4 | 2 vs. 3 | 2 vs. 4 | 3 vs. 4 | |

| Morningness-Eveningness Score | 2.51 | 0.06 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.02 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.1 |

| Bedtime - school nights | 3.64 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 0.02 |

| Wake time change (School to Weekend) | 0.13 | 0.9 | 0.8 | 0.6 | 0.5 | ∼1 | ∼1 | 0.9 |

| Time to fall asleep (School Night) | 2.48 | 0.06 | 0.3 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| Time to fall asleep (Weekend Night) | 2.48 | 0.06 | 0.50 | 0.008 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 0.6 |

| Any Sleep Problems (% Yes) | 3.27 | 0.02 | 0.6 | 0.004 | 0.03 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.2 |

| Waking during nights (% 2+ Times) | 2.82 | 0.04 | 0.6 | 0.006 | 0.08 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 0.2 |

| Poor sleeper (% Yes) | 5.68 | 0.0008 | 0.7 | 0.0003 | 0.0006 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.8 |

| Gets enough sleep (% Never/Sometimes) | 2.99 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 0.004 | 0.004 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

Group comparisons were evaluated after adjustment for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni in generalized linear models and Tukey in linear models.

Abbreviations: BP/OB – BP offspring of BP Parents; non-BP/OB – non-BP offspring of BP parents;

Demographic and Clinical Variables (Table 1)

Of the BP/OB, 17.0% (n=8) met criteria for BP-I, 10.6% (n=5) met criteria for BP-II and 72.3% (n=34) met criteria for BP-NOS. The three groups significantly differed on age, SES, and rates of living with both biological parents. Though the groups differed on age, they did not differ on the proportion who were pre-adolescent, adolescent, or adult (X2=2.34, p=0.67); across all groups, 68% of offspring were pre-adolescent (<13 years old), 30% were adolescent (13-17 years old), and 2% were adult (>17 years old) at baseline sleep assessment. As seen in Table 1, the groups differed significantly on lifetime rates of several psychiatric disorders and rate of parent non-BP Axis I disorder, and they differed significantly on mood symptom severity, based on the worst week in the past two months.

Parent Report of Child's Sleep

As compared to OC, the parents of the non-BP/OB reported significantly later child bedtime on weeknights (Table 2), and this difference remained when accounting for lifetime offspring comorbid diagnoses (eTable1).

BP/OB had significantly lower M/E scores per parent ratings as compared to the OC offspring, indicating a higher tendency towards eveningness (Table 2). Parents of BP offspring reported their children took a significantly longer time to fall asleep on weeknights than OC, and they were significantly more likely to be rated as a poor sleeper and to have inadequate sleep. Effect sizes for the continuous measures are small, but effects of the categorical measures range from small to large. The largest effect suggests that BP/OBP are 4.4 times more likely to be a poor sleeper than OC. When lifetime offspring comorbid diagnoses were entered in the models, only the proportion reporting inadequate sleep remained significantly different between BP/OB and OC (eTable1).

As compared to non-BP/OB, BP/OB took significantly longer to fall asleep on weeknights and weekend nights per parent report (Table 2). The BP/OB were significantly more likely to have any sleep problem and frequent nighttime awakenings, to be rated as a poor sleeper, and to have inadequate sleep. Here, the effects for continuous variables are small in size, while effects of categorical variables are medium to large. The largest effect shows BP/OBP being 4.2 times more likely to be a poor sleeper than non-BP/OB. Only the likelihood of having inadequate sleep remained significantly different between BP/OB and Non-BP/OB when lifetime offspring psychiatric disorders were entered into the model (eTable1).

To examine whether significant group differences in sleep and circadian factors were associated with current mood symptomatology we subdivided the BP/OB group into those individuals experiencing a current mood episode at the time of the SSHS (n=32), and those who were euthymic (n=12; n=3 did not have mood data at sleep baseline). After repeating the analyses above, including only those sleep parameters that differed significantly among the groups in the initial model, we found that the BP/OB offspring who were in a mood episode differed significantly on some sleep parameters from the non-BP/OB and the OC, but they did not differ significantly from the BP/OB who were not in a mood episode (Table 3). Moreover, BP/OB offspring who were not in a mood episode did not differ on any sleep parameters from the other groups.

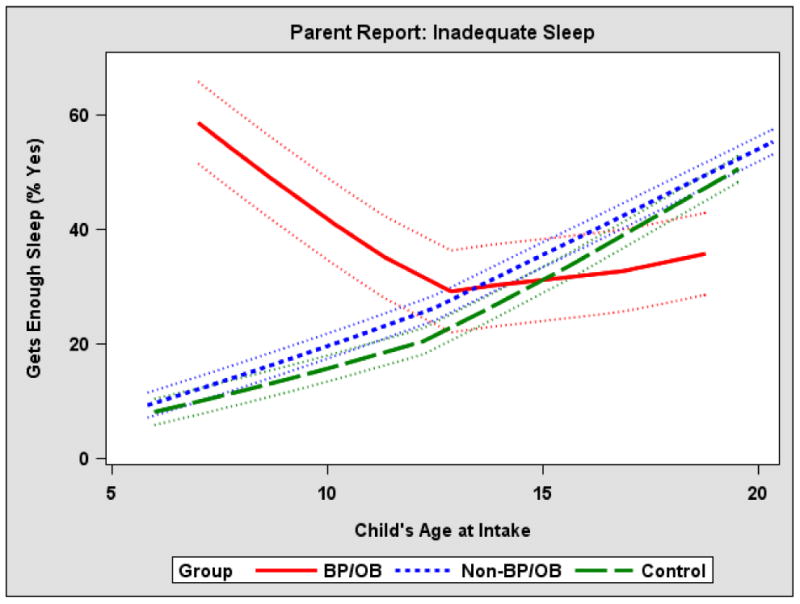

Age was added as a moderator to each model to determine whether group differences depended on age. Based on parent report, age significantly moderated the group effect on inadequate sleep (F=3.20, p=0.04), such that the proportion of parents of BP/OB participants who felt their child did not get enough sleep significantly exceeded that of the parents of non-BP/OB and control parents among the younger participants, but the groups did not significantly differ among the older participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Age moderates the impact of offspring group on parent-reported inadequate child sleep.

Summary

Even after accounting for child lifetime psychiatric disorders, BP/OB were significantly more likely to have inadequate sleep than non-BP/OB and OC. BP/OB who were in a mood episode did not differ from BP/OB who were not in mood episode on sleep or circadian variables, while BP/OB not in a mood episode has no significant difference from Non-BP/OB and OC. Last, age significantly moderated the group effect on inadequate sleep.

Child Self-Report of Sleep

Similar to the parent report, children reported significant group differences in morningness-eveningness score, and in the likelihood of having any sleep problem, frequent awakenings during the night, and inadequate sleep (eTable2). Whereas the parents reported that BP/OB offspring had significantly lower M/E scores as compared to OC, non-BP/OB offspring reported significantly lower M/E scores as compared to OC (small effect). Similar to parental report, BP/OB offspring were more likely to report frequent awakenings during the night than non-BP/OB offspring; additionally, BP/OB offspring were more likely to report any sleep problem and frequent awakenings during the night than OC (eTable2). Parent- and child-reported pairwise differences pertaining to inadequate sleep were similar, suggesting that BP/OB were more likely to have inadequate sleep than the other two groups. These effects were small to medium in size. Other significant differences observed based on parent report were not found based on the offspring's self-report.

Sleep and Circadian Factors in non-BP Offspring of BP parents who later converted to BP-spectrum

Demographic and Clinical Variables (Table 4)

Table 4. Non-BP/OB Offspring who have follow-up after baseline sleep assessment - demographics.

| Variable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Converters to BP-spectrum (n=40) | Non-Converters (n=314) | F Stat. | P - value | |

| Demographic Factors | ||||

| Gender (% female) | 62.5 | 48.1 | 2.89 | 0.09 |

| Lives with both biological parents (% yes) | 45.0 | 51.3 | 0.50 | 0.5 |

| Puberty (%Tanner stage 4 or 5) | 25.0 | 30.3 | 0.28 | 0.6 |

| Race (% White) | 85.0 | 81.9 | 0.10 | 0.8 |

| Age (years) - Mean (SD) | 11.3 (2.8) | 11.5 (3.7) | 0.09 | 0.8 |

| Socioeconomic Status - Mean (SD) | 34.6 (15.6) | 34.7 (14.2) | 0.00 | 0.97 |

| Follow-Up Length (Years) – Mean (SD) | 7.5 (1.6) | 6.2 (2.4) | 10.65 | 0.001 |

| Lifetime History of Diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Anxiety | 47.5 | 26.8 | 6.83 | 0.01 |

| ADHD | 41.0 | 22.6 | 5.77 | 0.02 |

| ODD | 18.0 | 10.2 | 1.77 | 0.2 |

| Conduct Disorder | 5.1 | 2.6 | 0.74 | 0.4 |

| Non-BP Axis I d/o in Parent Proband | 92.5 | 91.4 | 0.05 | 0.8 |

| Mood Symptom Severity (Worst Week in past 2 months) – Mean (SD) | ||||

| K-MRS (minus sleep item) | 4.9 (5.9) | 2.9 (4.4) | 6.42 | 0.01 |

| K-DRS (minus sleep items) | 20.5 (10.2) | 15.1 (5.9) | 23.50 | <0.0001 |

Abbreviations: BP – Bipolar; SD – standard deviation; ADHD – Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; ODD – Oppositional Defiant Disorder; D/O – disorder; K-MRS – KSADS Mania Rating Scale; K-DRS – KSADS Depression Rating Scale

Of the 386 non-BP/OB who had a SSHS report, 354 (91.7%) had at least one post-SSHS follow-up assessment. The average time from the parent-reported baseline SSHS to the last follow-up assessment was 6.4 years (median 6.8 years). Over the subsequent follow-up, 40 (11.3%) non-BP/OB were diagnosed with a BP-spectrum disorder (BP-I n=5, BP-II n=2, BPNOS n=33). The new onset of a BP-spectrum diagnosis occurred at a mean of 6.1 years after the SSHS assessment (median=6.1 years, SD=2.4 years). Converters had a significantly longer follow-up period after baseline SSHS than non-converters (mean=7.5 years, SD=1.6 vs. mean=6.2 years, SD=2.4). Accordingly, follow-up length was included as a covariate in our logistic regression models to control for this difference. Converters also were significantly more likely to report a lifetime diagnosis of anxiety and ADHD at SSHS baseline, and they reported higher symptom severity on K-MRS and K-DRS scales without sleep items.

Logistic Regression Predicting Conversion to BP

Automated logistic model selection procedures retained parent-reported extreme evening, frequent waking during the night, and inadequate sleep among their children (retention level=0.1). Manual selection further found time to fall asleep on weeknights to be significant at the 0.1 level (Table 5). When considering child-reported parameters, all automated model selection procedures retained time to fall asleep on weekends and frequent waking during the night (retention level=0.1). Manual selection also yielded the same model (Table 6). All effects were small to medium in size, with the largest showing that, based on parent report, those who converted to BP were 7.69 times less likely to be an extreme evening type than those who did not convert. Based on child report, the largest effect suggested that offspring with frequent waking during the night were 2.82 times more likely to convert to BP. Last, we re-ran the logistic regression models after controlling for child lifetime psychiatric disorders, as was done in other analyses (above). The results did not change meaningfully, with the exception of parent-report of child time to fall asleep on weeknights, which fell just below conventional levels of statistical significance (Table 5).

Table 5. Final logistic model using baseline sleep to predict conversion to BP among offspring of bipolar parents who have follow-up after baseline sleep assessment (Parent-Report of Offspring).

| Effect | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | F Value | p-value | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme Evening | 0.13 (inverse=7.69) | (0.02, 0.80) | 4.96 | 0.028 | 0.025 |

| Time to Fall Asleep on Weeknight (hours) | 2.09 | (1.06, 4.13) | 4.57 | 0.035 | 0.054 |

| Waking During Night | 4.01 | (1.41, 11.40) | 6.95 | 0.010 | 0.008 |

| Inadequate Sleep | 2.70 | (1.11, 6.55) | 4.89 | 0.029 | 0.032 |

Covariates were age, gender, follow-up length

p-value for each effect when child lifetime psychiatric disorders were added to the model.

Table 6. Final logistic model using baseline sleep to predict conversion to BP among offspring of bipolar parents who have follow-up after baseline sleep assessment (Child-Report of Self).

| Effect | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | F Value | p-value | p-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Fall Asleep on Weekend (hours) | 1.80 | (1.06, 3.04) | 4.90 | 0.029 | 0.031 |

| Waking during Night | 2.82 | (1.28, 6.19) | 6.82 | 0.010 | 0.017 |

Covariates were age, gender, follow-up length

p-value for each effect when child lifetime psychiatric disorders were added to the model.

Discussion

In this report we aimed to evaluate baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in the three offspring cohorts and to examine the association of baseline sleep parameters with subsequent conversion to BP among the non-BP/OB group. Our hypothesis that OB would have a greater tendency toward evening circadian phase was partially supported, with OB being more likely to be an evening type than OC. However, this difference did not remain when controlling for lifetime psychiatric diagnoses and after accounting for current mood symptoms. Our hypothesis that OB would have a larger discrepancy between weekend and weekday bedtimes and wake times as compared to OC was largely not supported. Though the omnibus test of wake time change showed significant differences among the groups based on parent report, the pairwise group comparisons were not statistically significant.

Our hypothesis that the OB would have higher rates of subjective sleep problems compared to OC (especially among the BP/OB group) was partially supported, a finding that is concordant with previous studies documenting sleep problems in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder.(49-51). The most consistent finding in our analyses showed that even when controlling for lifetime psychiatric disorders, BP/OB reported higher rates of inadequate sleep as compared to the other groups. Other group differences pertaining to having frequent awakenings during the night and being a poor sleeper did not remain after controlling for psychiatric diagnoses. While the BP/OB who were in a mood episode differed significantly from non-BP/OB and OC on several sleep parameters, BP/OB who were not in a mood episode did not. Moreover, BP/OB who were in a mood episode did not differ significantly on any sleep parameters from the BP/OB who were not in a mood episode. Thus, while lifetime diagnostic status plays at least a partial role in determining sleep, current mood state may play a role in explaining the differences even further. Still, the number of BP/OB who were not in a mood episode was relatively small, which may have accounted for the lack of significant difference between BP/OB who were not in a mood episode and the other groups. Future studies should explore these effects using larger samples that are likely to have enough power to detect an effect.

In addition, age moderated the impact of group on parent-reported inadequate sleep, such that the proportion of BP/OB with inadequate sleep significantly exceeded that of the other offspring groups among the younger participants. However, by the time participants reached early adolescence, normative changes in sleep and circadian rhythms may have occurred, leading to a much higher proportion of participants with inadequate sleep among all groups. Future studies should work to determine whether the high prevalence of inadequate sleep among younger participants with BP is a cause or consequence of the development of the disorder.

With regard to our hypothesis that baseline sleep and circadian phenotypes in the non-BP/OB subjects would be associated with future conversion to BP over subsequent longitudinal follow-up we found that parental ratings of child extreme evening type (extreme evening type associated with lower likelihood of conversion), frequent nighttime awakenings, and inadequate sleep predicted conversion to bipolar spectrum disorders among non-bipolar offspring of bipolar parents, whereas child report of time to fall asleep on weekends and frequent nighttime awakenings significantly predicted conversion. These differences were meaningful, with converters reporting about 15 minutes longer to fall asleep on weekends, and parents of converters reporting roughly 20.0% more waking during the night among their children as compared to parents of non-converters. This is the first report that we are aware of that prospectively demonstrates that subjective sleep problems in youth at genetic risk for BP are associated with the future onset of the illness. This finding is an interesting complement to the results of Rao and colleagues(52) who found that differences in sleep EEG (increased Stage 1 and decreased Stage 4) were associated with progression from unipolar depression to bipolar disorder in youth. Moreover, our finding that subjective sleep problems are associated with BP onset is in accord with results of other high-risk studies showing that the early natural history of BP unfolds in stages, with nonspecific psychopathology, including sleep disturbances, representing an early clinical manifestation of BP.(53) Still, that extreme evening type is associated with lower likelihood of conversion is not consistent with what has been documented in the literature. Many studies have shown that adolescents and adults with bipolar disorder are more likely to be evening types than controls. (e.g., 54;55;56) However, circadian preference tends to differ between childhood and adolescence, with several studies suggesting that there is a substantial shift to an evening circadian preference around 12-13 years of age.(29;45;57;58) Thus, because the average age of our sample was around 11 years, our finding may be explained by the possibility that we may not see this strong association until individuals reach adolescence.

The results reported here have meaningful clinical implications for prognosis and treatment. Consistent with some reports (21;22), measures of sleep and circadian rhythms may be a useful marker of heightened risk for disease onset in those already at genetic risk for BP. Our analyses suggest that of the sleep parameters derived from the SSHS, it is the subjective measures of sleep quality (i.e., inadequate sleep, waking during nights) that have the largest effect in discriminating the offspring groups. For example, BP/OB were 2.3 or 2.4 times more likely to report inadequate sleep (parent-reported) as compared to non-BP/OB and OC groups, respectively, effects which approach a medium size and which remain when controlling for lifetime psychiatric disorders. Alterations in this particular sleep problem could be interpreted as a possible trait characteristic and relevant biomarker of the disorder representing phenotype-specific susceptibility.(17;27;59-61) Moreover, inadequate sleep may have an especially important role among adolescents at-risk for BP given the high prevalence and damaging consequence of insufficient during the teenage years.(31;62;63) Because of insufficient weekday sleep, adolescents tend to engage in “catch up” sleep on the weekends,(30;64) which often leads to dramatic shifts in sleep-wake schedules from the weekend to the start of the school week. (65;66) While other measures relating to sleep timing and duration were found to be significantly different among the groups, the sizes of these effects were small. Thus, the subjective reports of sleep problems, rather than a specific measure of circadian preference or sleep timing/duration may have the biggest potential to serve as a trait characteristic of BP. Moreover, since sleep problems are malleable risk factors, it is both reasonable and sensible to target sleep interventions in at-risk offspring, particularly if there are already signs of such sleep difficulties. Indeed, preliminary findings from our research group show that a psychosocial treatment for adolescents at-risk for BP that focuses on stabilizing daily rhythms in the service of delaying or preventing the onset of BP contributed to changes in some sleep and circadian patterns.(67) These initial promising findings highlight the importance of early, sleep-focused intervention for youth at-risk for BP.

There are several possible reasons for the lack of findings between the offspring of BP parents and the community control offspring at baseline assessment of sleep, some of which are rooted in the limitations of the study. It is possible that questionnaire-based proxy measures of sleep and circadian phenotypes are not sensitive or reliable enough to detect early or subtle signs of sleep and circadian dysfunction, such as night-to-night variability in sleep timing or sleep fragmentation that may be outside of awareness. The SSHS was designed to measure usual or typical sleep patterns and circadian phase preference; however, it does not assess the variability of sleep and circadian rhythm beyond the weekday-weekend differences, nor does it assess the tendency for sleep and circadian dysregulation when these systems are stressed (e.g., when traveling across several time zones or staying up all night during an emergency). This has relevance for the current analysis because instability of circadian rhythm may be a key feature of BP that could be an enduring trait or present during the prodromal phase of illness.(24) Additionally, future studies may choose to employ alternative non-invasive ways of measuring sleep, such as wrist actigraphy, in order to provide an objective assessment of rest-activity rhythms.

An additional limitation is the 6.4 year average time span between baseline SSHS and conversion to BP among the non-BP/OB. Sleep patterns may have changed during this interval, calling into question the clinical significance of baseline sleep parameters in the development of BP 6 years later, and potentially aiding our understanding of the relatively small odds ratios. Future analyses will focus on the longitudinal relationship between sleep patterns and the development of BP over the course of follow-up. Other limitations of the study include the relatively small number of subjects converting to bipolar spectrum disorders, and the cross-sectional nature of our analyses, both of which have less power to detect factors that contribute to risk of illness onset in high-risk samples. Similarly, the sample sizes of BP/OB who were in a mood episode and BP/OB who were not in a mood episode were relatively small, potentially reducing our likelihood of finding significant differences between these two groups. It is also possible that power to detect differences between the groups may have been limited in the supplementary analyses that included additional covariates, an approach which may enhance the chance for false negative findings. Last, we used Tukey and Bonferroni corrections for the numerous multiple comparisons included in this study. Though we included hypotheses, there were several outcome variables available to test each hypothesis, increasing the number of analyses. It is likely that we would have found additional significant differences between OB and OC without this correction. Thus, small p-values that were found to be marginally non-significant are worth consideration in future analyses.

In summary, most sleep disturbances found in offspring of parents with BP were secondary to psychopathology in general. However, even when lifetime comorbid disorders were considered, BP/OB continued to have significantly higher rates of inadequate sleep as compared to both non-BP/OB and OC. BP/OB offspring who were in a mood episode differed significantly on some sleep parameters from the non-BP/OB and the OC, while BP/OB offspring who were not in a mood episode did not. BP/OB who were in a mood episode did not differ significantly on any sleep parameters from the BP/OB who were not in a mood episode. This would be consistent with sleep/circadian disruption existing as a “state” marker that goes with the presence of active illness, instead of a “trait” that is present prior to illness, during periods of euthymia and in subset of those at genetic risk of BP who will not go on to have BP. However, it is likely that the number of BP/OB participants not in a mood episode in our sample was too small to detect significant differences among the groups, so future work should re-test this with a larger sample that will have sufficient power to detect an effect. Moreover, several sleep and circadian parameters may play a role in the pathophysiology of BP, but these disturbances may be affected by normative changes in sleep and circadian rhythms that occur over the course of adolescent development. Future studies will be required to further disentangle whether sleep and circadian disruptions are causes or consequences of mood symptomatology in BP, and how this disruption affects, or is affected by, development.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all BIOS study interviewers and all families who participated in the BIOS study.

Disclosures: This work was supported by MH060952 (PI B. Birmaher). Dr. Birmaher's research is funded by the NIMH. He has or will receive royalties from Random House, Inc., Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, and UpToDate. He is currently employed by the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center/Western Psychiatric Institute and Clinic. Dr. Brent receives royalties from Guilford press, from the electronic self-rated version of the C-SSRS, and from ERT, Inc. He also serves on the editorial board of UpToDate. Dr. David Kupfer has the following conflicts of interest: Holds joint ownership of copyright for the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI); he and his spouse, Dr. Ellen Frank are stockholders in Psychiatric Assessments, Inc., and Health Rhythms, Inc. He is a stockholder in AliphCom. Dr. Frank also has the following conflicts of interest: received royalties from the American Psychological Association and Guilford Press; member of the Advisory Board of Servier International; Editorial Consultant for the American Psychiatric Press. Dr. Levenson receives royalties from American Psychological Association books and receives grant support from the American Psychological Foundation. She is supported by HL082610 (T32, PI D. Buysse). Dr. T. Goldstein receives royalties from Guilford Press and grant support from NIMH, NIDA, NICHD, and The Pittsburgh Foudnation. Dr. Sakolsky is employed by the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and the University of Pittsburgh Physicians. Her research is funded by NIMH and has been funded by NARSAD; she received an honorarium from the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry for teaching; she serves as an editorial board member of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology News and as a specialty consultant for the Prescriber's Letter. Dr. Sakolsky's husband was a computer programmer for ThermoFisher Scientific from July 2009 to July 2014. Drs. Angulo, Axelson, Diler, and B. Goldstein, and Ms. Hickey, Mr. Merranko, and Ms. Monk have no disclosures.

Reference List

- 1.Mistlberger RE, Rusak B. Circadian rhythms in mammals: formal properties and environmental influences. In: Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC, editors. Principles and Practices of Sleep Medicine. 5th. St. Louis: Elsevier Sunders; 2011. pp. 363–75. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic-Depressive Illness. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Milhiet V, Boudebesse C, Bellivier F, Drouot X, Henry C, Leboyer M, Etain B. Circadian abnormalities as markers of susceptibility in bipolar disorders. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2014;6:120–37. doi: 10.2741/s419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng TH, Chung KF, Ho FY, Yeung WF, Yung KP, Lam TH. Sleep-wake disturbance in interepisode bipolar disorder and high-risk individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2014 Jun 26; doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2014.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robillard R, Naismith SL, Rogers NL, Scott EM, Ip TK, Hermens DF, Hickie IB. Sleep-wake cycle and melatonin rhythms in adolescents and young adults with mood disorders: comparison of unipolar and bipolar phenotypes. Eur Psychiatry. 2013 Sep;28(7):412–6. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robillard R, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, White D, Rogers NL, Ip TK, Mullin SJ, Alvares GA, Guastella AJ, Smith KL, Rong Y, Whitwell B, Southan J, Glozier N, Scott EM, Hickie IB. Ambulatory sleep-wake patterns and variability in young people with emerging mental disorders. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2014 Sep 9;39(5):130247. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harvey AG, Schmidt DA, Scarna A, Semler CN, Goodwin GM. Sleep-related functioning in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder, patients with insomnia, and subjects without sleep problems. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 Jan;162(1):50–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey AG. Sleep and circadian rhythms in bipolar disorder: seeking synchrony, harmony, and regulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;165(7):820–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millar A, Espie CA, Scott J. The sleep of remitted bipolar outpatients: a controlled naturalistic study using actigraphy. J Affect Disord. 2004 Jun;80(2-3):145–53. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00055-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salvatore P, Ghidini S, Zita G, De PC, Lambertino S, Maggini C, Baldessarini RJ. Circadian activity rhythm abnormalities in ill and recovered bipolar I disorder patients. Bipolar Disord. 2008 Mar;10(2):256–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00505.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones SH, Hare DJ, Evershed K. Actigraphic assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005 Apr;7(2):176–86. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geoffroy PA, Boudebesse C, Bellivier F, Lajnef M, Henry C, Leboyer M, Scott J, Etain B. Sleep in remitted bipolar disorder: a naturalistic case-control study using actigraphy. J Affect Disord. 2014 Apr;158:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2014.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rocha PM, Neves FS, Correa H. Significant sleep disturbances in euthymic bipolar patients. Compr Psychiatry. 2013 Oct;54(7):1003–8. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2013.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.St-Amand J, Provencher MD, Belanger L, Morin CM. Sleep disturbances in bipolar disorder during remission. J Affect Disord. 2013;146(1):112–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seleem MA, Merranko JA, Goldstein TR, Goldstein BI, Axelson DA, Brent DA, Nimgaonkar VL, Diler RS, Sakolsky DJ, Kupfer DJ, Birmaher B. The longitudinal course of sleep timing and circadian preferences in adults with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2014 Dec 19; doi: 10.1111/bdi.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey AG. The adverse consequences of sleep disturbance in pediatric bipolar disorder: implications for intervention. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009 Apr;18(2):321–38. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staton D. The impairment of pediatric bipolar sleep: hypotheses regarding a core defect and phenotype-specific sleep disturbances. J Affect Disord. 2008 Jun;108(3):199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harvey AG, Mullin BC, Hinshaw SP. Sleep and circadian rhythms in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Dev Psychopathol. 2006;18(4):1147–68. doi: 10.1017/S095457940606055X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leibenluft E, Albert PS, Rosenthal NE, Wehr TA. Relationship between sleep and mood in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1996;63(2-3):161–8. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02854-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauer M, Glenn T, Grof P, Rasgon N, Alda M, Marsh W, Sagduyu K, Schmid R, Adli M, Whybrow PC. Comparison of sleep/wake parameters for self-monitoring bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009 Aug;116(3):170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Egeland JA, Hostetter AM, Pauls DL, Sussex JN. Prodromal symptoms before onset of manic-depressive disorder suggested by first hospital admission histories. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 Oct;39(10):1245–52. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200010000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffy A, Alda M, Hajek T, Sherry SB, Grof P. Early stages in the development of bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2010 Feb;121(1-2):127–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer TD, Maier S. Is there evidence for social rhythm instability in people at risk for affective disorders? Psychiatry Res. 2006 Jan 30;141(1):103–14. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ankers D, Jones SH. Objective assessment of circadian activity and sleep patterns in individuals at behavioural risk of hypomania. J Clin Psychol. 2009 Oct;65(10):1071–86. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones SH, Tai S, Evershed K, Knowles R, Bentall R. Early detection of bipolar disorder: a pilot familial high-risk study of parents with bipolar disorder and their adolescent children. Bipolar Disord. 2006 Aug;8(4):362–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bullock B, Murray G. Reduced amplitude of the 24-hr activity rhythm: a biomarker of vulnerability to bipolar disorder? Clinical Psychological Science. 2014;2:86–98. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Etain B, Jamain S, Milhiet V, Lajnef M, Boudebesse C, Dumaine A, Mathieu F, Gombert A, Ledudal K, Gard S, Kahn JP, Henry C, Boland A, Zelenika D, Lechner D, Lathrop M, Leboyer M, Bellivier F. Association between circadian genes, bipolar disorders and chronotypes. Chronobiol Int. 2014 Aug;31(7):807–14. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2014.906445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jenni OG, Achermann P, Carskadon MA. Homeostatic sleep regulation in adolescents. Sleep. 2005 Nov;28(11):1446–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carskadon MA, Vieira C, Acebo C. Association between puberty and delayed phase preference. Sleep. 1993 Apr;16(3):258–62. doi: 10.1093/sleep/16.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Crowley SJ, Acebo C, Carskadon MA. Sleep, circadian rhythms, and delayed phase in adolescence. Sleep Med. 2007 Sep;8(6):602–12. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Jenni OG. Regulation of adolescent sleep: implications for behavior. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004 Jun;1021:276–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1308.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Monk K, Kalas C, Goldstein B, Hickey MB, Obreja M, Ehmann M, Iyengar S, Shamseddeen W, Kupfer D, Brent D. Lifetime psychiatric disorders in school-aged offspring of parents with bipolar disorder: the Pittsburgh Bipolar Offspring study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;66(3):287–96. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.American Psychiatric A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spitzer R, Gibbon M, Williams J. Structured Clinical Interview for Axis I DSM-IV Disorders (SCID) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997 Jul;36(7):980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Frazier TW, Demeter CA, Youngstrom EA, Calabrese JR, Stansbrey RJ, McNamara NK, Findling RL. Evaluation and comparison of psychometric instruments for pediatric bipolar spectrum disorders in four age groups. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007 Dec;17(6):853–66. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Axelson D, Birmaher BJ, Brent D, Wassick S, Hoover C, Bridge J, Ryan N. A preliminary study of the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children mania rating scale for children and adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13(4):463–70. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Axelson D, Birmaher B, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Bridge J, Keller M. Phenomenology of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Oct;63(10):1139–48. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, Ryan N, Leonard H, Hunt J, Iyengar S, Keller M. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006 Feb;63(2):175–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, Boxer A. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. J Youth Adolesc. 1988 Apr;17(2):117–33. doi: 10.1007/BF01537962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969 Jun;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970 Feb;45(239):13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hollingshead A. Four-factor index of social status. New Haven CT: Yale University, Department of Sociology; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA. Sleep schedules and daytime functioning in adolescents. Child Dev. 1998 Aug;69(4):875–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gau SF, Soong WT. The transition of sleep-wake patterns in early adolescence. Sleep. 2003 Jun 15;26(4):449–54. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Giannotti F, Cortesi F, Sebastiani T, Ottaviano S. Circadian preference, sleep and daytime behaviour in adolescence. J Sleep Res. 2002 Sep;11(3):191–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.2002.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfson AR, Carskadon MA, Acebo C, Seifer R, Fallone G, Labyak SE, Martin JL. Evidence for the validity of a sleep habits survey for adolescents. Sleep. 2003 Mar 15;26(2):213–6. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russo PM, Bruni O, Lucidi F, Ferri R, Violani C. Sleep habits and circadian preference in Italian children and adolescents. J Sleep Res. 2007 Jun;16(2):163–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2007.00584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mehl RC, O'Brien LM, Jones JH, Dreisbach JK, Mervis CB, Gozal D. Correlates of sleep and pediatric bipolar disorder. Sleep. 2006 Feb;29(2):193–7. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lofthouse N, Fristad M, Splaingard M, Kelleher K. Parent and child reports of sleep problems associated with early-onset bipolar spectrum disorders. J Fam Psychol. 2007 Mar;21(1):114–23. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lofthouse N, Fristad M, Splaingard M, Kelleher K, Hayes J, Resko S. Web survey of sleep problems associated with early-onset bipolar spectrum disorders. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008 May;33(4):349–57. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsm126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rao U, Dahl RE, Ryan ND, Birmaher B, Williamson DE, Rao R, Kaufman J. Heterogeneity in EEG sleep findings in adolescent depression: unipolar versus bipolar clinical course. J Affect Disord. 2002 Aug;70(3):273–80. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(01)00396-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duffy A. The early natural history of bipolar disorder: what we have learned from longitudinal high-risk research. Can J Psychiatry. 2010 Aug;55(8):477–85. doi: 10.1177/070674371005500802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wood J, Birmaher B, Axelson D, Ehmann M, Kalas C, Monk D, Turkin S, Kupfer DJ, Brent D, Monk TH, Nimgaonkar VL. Replicable difference in preferred circadian phase between bipolar disorder patient and control individuals. Psychiatry Res. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Seleem MA, Merranko JA, Goldstein TR, Goldstein BI, Axelson DA, Brent DA, Nimgaonkar VL, Diler RS, Sakolsky DJ, Kupfer DJ, Birmaher B. The longitudinal course of sleep timing and circadian preferences in adults with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2015 Jun;17(4):392–402. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim KL, Weissman AB, Puzia ME, Cushman GK, Seymour KE, Wegbreit E, Carskadon MA, Dickstein DP. Circadian Phase Preference in Pediatric Bipolar Disorder. J Clin Med. 2014;3(1):255–66. doi: 10.3390/jcm3010255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tonetti L, Adan A, Di ML, Randler C, Natale V. Measures of circadian preference in childhood and adolescence: A review. Eur Psychiatry. 2015 Jul;30(5):576–82. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tonetti L, Fabbri M, Natale V. Sex difference in sleep-time preference and sleep need: a cross-sectional survey among Italian pre-adolescents, adolescents, and adults. Chronobiol Int. 2008 Sep;25(5):745–59. doi: 10.1080/07420520802394191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Murray G, Harvey AG. Circadian rhythms and sleep in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12:459–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2010.00843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Harvey AG. Sleep and circadian rhythms in bipolar disorder: seeking synchrony, harmony, and regulation. Am J Psychiatry. 2008 Jul;165(7):820–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08010098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McClung CA. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013 Aug 15;74(4):242–9. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moran AM, Everhart DE. Adolescent sleep: review of characteristics, consequences, and intervention. Journal of Sleep Disorders: Treatment & Care. 2012;1(2) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shochat T, Cohen-Zion M, Tzischinsky O. Functional consequences of inadequate sleep in adolescents: A systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2014 Feb;18(1):75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Sleep Foundation poll task force. Teens and Sleep 2006 Sleep in America poll. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wittmann M, Dinich J, Merrow M, Roenneberg T. Social jetlag: misalignment of biological and social time. Chronobiol Int. 2006;23(1-2):497–509. doi: 10.1080/07420520500545979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Touitou Y. Adolescent sleep misalignment: a chronic jet lag and a matter of public health. J Physiol Paris. 2013 Sep;107(4):323–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jphysparis.2013.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldstein TR, Fersch-Podrat R, Axelson DA, Gilbert A, Hlastala SA, Birmaher B, Frank E. Early intervention for adolescents at high risk for the development of bipolar disorder: pilot study of Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) Psychotherapy (Chic) 2014 Mar;51(1):180–9. doi: 10.1037/a0034396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]