Abstract

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection affects approximately 3% of the world's population and causes chronic liver diseases, including liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma. Although current antiviral therapy comprising direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) can achieve a quite satisfying sustained virological response (SVR) rate, it is still limited by viral resistance, long treatment duration, combined adverse reactions, and high costs. Moreover, the currently marketed antivirals fail to prevent graft reinfections in HCV patients who receive liver transplantations, probably due to the cell-to-cell transmission of the virus, which is also one of the main reasons behind treatment failure. HCV entry is a highly orchestrated process involving initial attachment and binding, post-binding interactions with host cell factors, internalization, and fusion between the virion and the host cell membrane. Together, these processes provide multiple novel and promising targets for antiviral therapy. Most entry inhibitors target host cell components with high genetic barriers and eliminate viral infection from the very beginning of the viral life cycle. In future, the addition of entry inhibitors to a combination of treatment regimens might optimize and widen the prevention and treatment of HCV infection. This review summarizes the molecular mechanisms and prospects of the current preclinical and clinical development of antiviral agents targeting HCV entry.

Keywords: antiviral target, entry factor, entry inhibitor, hepatitis C virus, hepatocyte

Introduction

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) belongs to the family Flaviviridae and infects more than 180 million people worldwide. HCV infection is considered as a major public health problem and consumes millions of dollars in medical expenses every year.1,2 HCV has a total of seven identified genotypes, with more than 50 subtypes and millions of quasispecies. The high variability and complexity of the virus make it difficult to manufacture effective prophylactic or therapeutic vaccines to prevent the pathogen from spreading. Approximately 70% of acutely infected patients will ultimately develop chronic infections despite the implementation of advanced medical care and intervention.3 Due to its biological characteristics, HCV infection is one of the leading causes of liver-associated diseases, such as cirrhosis, steatosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, whose end-stage patients require liver transplantation to stay alive.4 Unfortunately, the reinfection of a graft is difficult to avoid due to the lack of preventive strategies.5

The previously recommended treatment for HCV infection was a combination therapy consisting of PEGylated interferon alpha and ribavirin.3 In recent years, HCV treatment has undergone a groundbreaking evolution. Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), such as protease inhibitors (boceprevir or telaprevir in 2011), have revolutionized the current status of HCV treatment. Triple-combination therapy improves sustained virological response (SVR) rates in naive genotype 1 patients by more than 70%. However, the two first-generation protease inhibitors that are typically used easily lead to the development of drug-resistant variants, and concomitant adverse reactions such as fatigue or anemia unavoidably reduce patient compliance with the regimen.4,6,7 A second-wave first-generation protease inhibitor, simeprevir, and a nucleotide analog, sofosbuvir, were approved by the United States in 2013 via the FDA and by Europe in 2014 for the treatment of hepatitis C (HC).7,8,9 In October 2014, the use of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir was approved by the FDA, and in December, an interferon-free regimen including an ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir combination tablet and dasabuvir was also approved for the treatment of genotype 1 patients.10,11,12,13,14,15 A number of other DAAs and host-targeted agents (HTAs) are undergoing clinical trials. Daclatasvir is an NS5A inhibitor and is currently being evaluated in an advanced clinical trial as a component of a combination therapy.16 In fact, the combination of daclatasvir and asunaprevir (an HCV NS3/4A protease inhibitor) has been approved for the treatment of genotype 1 patients in Japan.16 The future of HCV therapy is likely to be consist of interferon-free regimens with pan-genotypic activity, higher antiviral efficiencies, shorter treatment durations, and fewer adverse reactions. The emerging novel antivirals should optimize the treatment options, especially for difficult-to-treat patients, such as those who are suffering from advanced liver diseases or other co-infections and who have poor response rates to current regimens.17,18

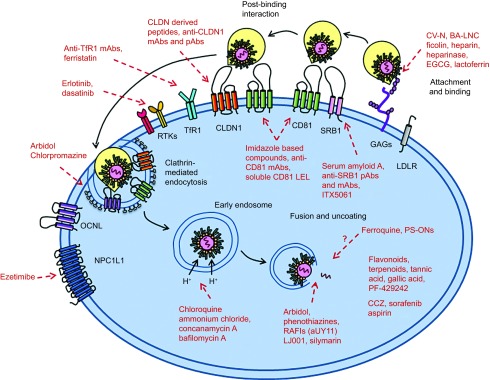

HCV entry represents the beginning of viral infection, which is highly orchestrated and essential in initiating viral infection and spread. HCV entry includes the initial recruitment and attachment of the virus to hepatocytes, post-binding interactions with host entry factors, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, and a final low pH-triggered membrane fusion to release viral RNA into the cytosol (Figure 1). The blocking of viral entry can efficiently eradicate HCV infection at the very first step, before viral genomes start to emerge, and might prevent cell-to-cell transmission, which is also required for viral spread. The current antiviral agents that are on the market or being evaluated in clinical trials mainly focus on targeting HCV nonstructural protein maturation or viral RNA synthesis. Although the currently used cocktail therapy is believed to cure more than 90% of infected patients, the appearance of viral resistance, null responders or treatment failure, superimposed with the adverse effects caused by the drugs, is still a major limitation that must be resolved.19 As an RNA virus, HCV very easily develops a resistance to antiviral treatments due to its error-prone replication property. Most entry inhibitors target host components, such as receptors or key enzymes, which are required for HCV entry and definitely have high genetic barriers to resistance due to their conserved nature. Therefore, these inhibitors tend to not only have pan-genotypic activity against virus infection but also have a greater risk of simultaneously causing cellular toxicity. Moreover, as the initial step of the viral life cycle has been blocked, entry inhibitors also have prophylactic properties. Because entry inhibitors target a different stage of the viral life cycle than the currently used anti-HCV drugs, they might have a synergistic effect when combined with the current regimens, especially with DAAs, providing multiple novel targets and new insight into antiviral strategies and complementary existing antiviral interventions, such that viral clearance may finally be achieved. This article reviews the entry inhibitors that are currently in development.

Figure 1.

HCV entry into hepatocytes and antiviral agents targeting entry factors. The HCV lipoviral particle (LVP) is recruited and binds to glycosaminoglycans and low-density lipoprotein receptor on host cells. After binding, the virions interact with a series of entry factors. SRB1 plays a role in both binding and post-binding. CD81 interacts with HCV E2, forms a complex with claudin-1 (CLDN1), and mediates HCV movement to the tight-junction areas. This process is regulated by the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) family, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2). The virions internalize into host cells by clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1) facilitates viral entry after CD81, possibly during HCV particle endocytosis. Niemann Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) plays an important role in cholesterol transportation and is a cofactor for HCV entry during post-binding steps. Low pH-dependent membrane fusion between endosome and HCV particle. Red words and lines indicate the antiviral agents targeting different stages and factors of HCV entry.

HCV entry into hepatocytes

Initial low-affinity attachment and binding

In vivo, circulating HCV particles reach the basolateral surfaces of hepatocytes, where the virus first binds to several receptors with low affinity, allowing it to become concentrated on the host cells' surfaces to enable subsequent interactions with other essential entry factors (Figure 1). These attachment factors include glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) on heparan sulfate (HS) and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR). Both of these receptors are able to interact with viral envelope proteins and apoE on lipo-virion particles (LVPs).20,21,22 HCV exists as LVP with LDL and VLDL in the circulatory systems of chronically infected patients. Recent studies have demonstrated that LDLR plays an important role in HCV attachment to target cells.23 The knockdown of this receptor by small interfering RNA (siRNA) potently reduces virus infectivity, and a soluble form of LDLR can impair virus binding by interacting with HCV particles.24 Although this receptor is dispensable for lipid/cholesterol-free HCVpp entry, productive HCV infection, including viral entry and replication, requires the involvement of LDLR.24,25

The lectin cyanovirin-N (CV-N) is a type of carbohydrate-binding agent that has potent antiviral activity against HCV. This small compound impairs virus binding by interacting with viral envelope glycoproteins at their high-mannose oligosaccharides (Table 1).26 Recent studies have identified boronic acid-modified lipid nanoparticles (BA-LNC) as potent inhibitors of HCV entry through a mechanism similar to that of lectins. BA-LNCs could be used as a pseudolectin-based therapeutic agent to develop novel HCV entry inhibitors.27 Ficolins are a type of serum protein related to collectins.28 Neutralizing concentrations of L-ficolin can be found in the sera of HCV-infected patients. Additionally, a recent study shows that recombinant human L-ficolin can neutralize HCV particles directly and inhibit virus attachment by neutralizing the viral glycoproteins E1 and E2.29 Heparin is a structural analog of HS that can competitively inhibit virus binding to host cells. A series of heparin-derived molecules are undergoing evaluation for their potential to serve as anti-HCV agents.21,90 Heparanase, an enzyme that degrades HS on host cell surfaces, can also impede both HCV E2 and HCVcc binding to host cell surfaces (Table 1).21

Table 1. The process of viral entry and targets for antiviral agents with their development stage.

| Process of entry | Target | Representatives of compounds | Developmental stage | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attachment | Lectin cyanovirin-N | Cell culture | 26 | |

| BA-LNC | Cell culture | 27 | ||

| Ficolin | Cell culture | 28,29 | ||

| Heparin and heparin-derived compounds | Cell culture | 21,28 | ||

| Heparanase | Cell culture | 21 | ||

| EGCG and its derivatives | Cell culture | 30,31,32 | ||

| Lactoferrin | Phase I | 33,34,35 | ||

| A p7 ion channel-derived peptide H2-3 | Cell culture | 36 | ||

| Post-binding interactions with entry factors | CD81 | Imidazole-based compounds | Cell culture | 37 |

| Anti-CD81 mAbs | Mouse model | 38,39,40,41,42,43 | ||

| Soluble CD81 LEL | Cell culture | 42,44,45,46,47,48 | ||

| SRB1 | Serum amyloid A | Cell culture | 49,50 | |

| Anti-SRB1 pAb and mAb | Mouse model | 51,52,53,54 | ||

| ITX5061 | Phase I/IIa | 55,56,57,58 | ||

| CLDN1 | Anti-CLDN1 peptides | Cell culture | 59 | |

| Anti-CLDN1 pAb and mAb | Mouse model | 60,61,62 | ||

| EGFR | Erlotinib | Phase I/IIa | 63 | |

| EphA2 | Dasatinib | Cell culture | 63 | |

| TfR1 | Anti-TfR1 mAbs | Cell culture | 64 | |

| Ferristatin | Cell culture | 64 | ||

| NPC1L1 | Anti-NPC1L1 mAbs | Cell culture | 65 | |

| Ezetimibe | Mouse model | 66 | ||

| Clathrin-mediated endocytosis | Chlorpromazine | Cell culture | 67 | |

| Arbidol | Cell culture | 68 | ||

| Fusion and uncoating | Endosome acidification | Concanamycin A | Cell culture | 69 |

| Bafilomycin A | Cell culture | 69 | ||

| Chloroquine | Cell culture | 70,71 | ||

| Ammonium chloride | Cell culture | 70,71 | ||

| Lipid composition of virus or host cell | Arbidol | Cell culture | 72 | |

| Phenothiazines | Cell culture | 73 | ||

| RAFIs (aUY11) | Cell culture | 74,75 | ||

| LJ001 | Cell culture | 76 | ||

| Silymarin | Cell culture | 77,78 | ||

| Unclear mechanism | Ferroquine | Cell culture | 79 | |

| PS-ONs | Mouse model | 80 | ||

| Natural compounds and small molecules | Flavonoids, terpenoids, tannic acid, gallic acid, PF-429242 | Cell culture | 81,82,83,84,85,86 | |

| FDA-approved drugs | CCZ, sorafenib, aspirin | Phase Ib Cell culture | 87,88,89 |

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) and its derivatives are natural polyphenol compounds that are abundant in green tea extracts and have long been considered to regulate lipid metabolism, thereby having the potential to affect a variety of diseases.91 Studies suggest that EGCG and its derivatives impair virus binding to the host cell by interfering with virion E1/E2 function and simultaneously blocking cell-to-cell transmission in vitro (Table 1).30,31,32 Additionally, limited sampling estimates of EGCG in HCV patients suggest that a single oral dose of up to 400 mg of this green tea extract is safe and well tolerated.92 Additional experiments are needed to evaluate the possibility of using this compound as a candidate for anti-HCV therapy.

Lactoferrin (LF) is an iron-binding glycoprotein that belongs to the transferrin family; it is abundant in milk and most biological fluids.93 The antiviral activity of LF is relatively well understood. LF is thought to function by directly interfering with HCV particles to prevent their attachment to host cells both in vitro and in vivo.33 Bioactive peptides, such as the N-lobe or C-lobe of LF, also inhibit virus infection.35 Among all species, camel lactoferrin (cLF) shows the most effective antiviral property and is now being evaluated in a clinical trial (Table 1).34

The p7 is a polypeptide of the HCV-encoded protein in the endoplasmic reticulum membrane and is essential for infectious viral production in vivo.94,95 A recent study revealed that a p7 ion channel-derived peptide H2-3 potently inhibits HCV entry by directly affecting virus binding to the cell surface and interfering with the virus–host interaction (Table 1).36

Post-binding interactions with specific entry factors

Subsequent to virus binding, LVPs start to form contacts with a series of entry factors on host cells. Targeting these relatively conserved factors, which are indispensable for the early life cycle of the virus, builds up genetic barriers against antiviral agents. HCV entry requires several host factors, including the tetraspanin molecule CD81, scavenger receptor class B type 1 (SRB1), the tight junction (TJ) proteins claudin-1 (CLDN1) and occludin (OCLN), transferring receptor 1 (TfR1), the receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and ephrin receptor A2 (EphA2), and Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) cholesterol uptake receptor (Figure 1).

CD81 was the first of these factors to be identified and is the best understood HCV entry factor. It is a ubiquitously expressed, 26 kDa transmembrane protein that consists of a small extracellular loop (SEL) and a large extracellular loop (LEL).96,97,98 The CD81 LEL is believed to interact with the HCV E2 protein, which contributes directly to HCV infection. Imidazole-based compounds simulate the D-helix of CD81 and are relatively safe small molecule inhibitors of HCV. They selectively abrogate the function of CD81 during HCV entry, while the remaining physiological functions of CD81 are basically preserved (Table 1).37 Specific anti-CD81 monoclonal antibodies (mAbs), such as JS-81 or the newly developed K04, counteract E2-CD81 interactions, interfering with viral entry during a post-binding process and inhibit HCV infection in humanized mice (Table 1).38,39,40,41,42,43 A soluble recombinant form of CD81 LEL shows effective anti-HCV activity and is able to inhibit the entry of HCVpp, HCVcc, and serum-derived HCV, as well as HCV infection, in vivo (Table 1).42,44,45,46,47,48 However, because CD81 is widely distributed in all tissues, the toxicity issues that are associated with using CD81-based antibodies or compounds should be evaluated carefully.

SRB1 is a horseshoe-shaped glycoprotein that is closely related to lipid metabolism. SRB1 binds diverse lipoproteins, including HDL, LDL, and oxLDL and plays key roles in bidirectional cholesterol transport, possibly modulating HCV entry into host cells.99,100 The extracellular loop of SRB1 interacts with the HCV E2 HVR1 region and is required for viral entry during both binding and post-binding steps.51,101 Serum amyloid A (SAA) is an acute-phase protein that is produced by the liver.102,103 There is a close relationship between SAA and HDL in modulating HCV infectivity.50 SRB1 binds to and internalizes SAA, and SAA inhibits HCV entry by interacting with the virus (Table 1).49,50 Antibodies targeting SRB1 inhibit virus infection and spread both in vitro and in a humanized mouse model (Table 1).51,52,53,54 The preclinical compound ITX5061 is a small-molecule antiviral that impedes the uptake of HDL through SRB1, thus blocking the uptake of viral particles.55,56 An in vitro study indicated that ITX5061 functions synergistically with DAAs, making it a promising candidate for future combination therapy.57 This compound has just finished evaluation in a phase Ib study and is now undergoing a phase II clinical trial in HCV-positive patients (Table 1).58

CLDNs and OCLNs are components of TJs. CLDN1 is believed to form a complex with CD81 and to contribute to efficient HCV internalization.104,105,106 The expression of CLDN1, CD81, and SRB1 can confer HCVpp entry into HEK293 cells.107 CLDN1 is highly expressed in hepatocytes, making it an ideal and promising target for the development of specific prophylactic antiviral agents.108 A human CLDN1-derived peptide (CL58) was screened out from an overlapping peptide library and was confirmed to have antiviral activity during a late post-binding step without affecting TJ integrity (Table 1).59 CLDN1 mAbs and pAbs show potent inhibitory effects on HCV infection, probably because they can neutralize E2-CD81-CLDN1 associations with low toxicity in primary human hepatocytes (PHHs) and humanized mice (Table 1).60,61,62 However, a recent study has suggested that broad CLDN tropism permits its escape from CLDN1 Abs because the virus can utilize CLDN6 proteins in the same cell, providing new insight into CLDN usage during HCV infection.109 OCLN is also a key entry factor for HCV, as the expression of human OCLN and CD81 in mouse liver leads to viral permissivity in this originally non-susceptible animal model, while the silencing of this receptor perturbs HCV entry during a late post-binding step.110,111,112 A recent study found that the overexpression of miR-122 can decrease HCV entry by downregulating OCLN.113

EGFR and EphA2 are two well-understood RTKs and have recently been identified as host cofactors of HCV entry by a functional siRNA kinase screen.63 These two kinases are highly expressed in human liver, and their specific inhibitors erlotinib (an EGFR inhibitor) and dasatinib (an EphA2 inhibitor), two clinically approved anticancer compounds, significantly impair viral entry in both polarized hepatoma cells and PHHs; erlotinib has also been effective in human-liver chimeric mice (Table 1).63 RTKs modulate viral entry at post-binding steps by interfering with CD81–CLDN1 complex association and blocking cell-to-cell transmission, all of which makes these two RTKs promising targets for developing anti-HCV agents, especially for the prevention of graft reinfection in chronic HCV patients who must undergo liver transplantation.114 Still, the specific efficacy and safety of using the currently licensed inhibitors of RTKs in HCV treatment requires further clinical evaluation.

Clinical observational data suggest that an iron metabolic disorder might occur in HCV-positive patients.115,116,117 Transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), an iron uptake receptor, is widely expressed in mammalian cells, including hepatocytes, and its trafficking protein (TTP) is involved in HCV entry. Both a specific anti-TfR1 mAb and a TfR1 inhibitor, ferristatin, impede HCV infection without affecting viral RNA replication when treatment is applied before virus incubation (Table 1).64 Kinetic experiments suggest that TfR1 facilitates HCV entry at a post-binding step, most likely after CD81.64 Further studies are needed to identify the functional domain of TfR1 that is used during HCV entry, which will enable the development of specifically targeted antiviral agents. However, HCV cell-to-cell transmission is not completely reduced after treatment with either the anti-TfR1 antibody or the TfR1 inhibitor, indicating that a different potential mechanism might be involved in this process.

NPC1L1 is a 13 transmembrane cholesterol transport receptor that is highly expressed on the apical surfaces of human enterocytes and the canalicular membranes of human hepatocytes.118,119 The main function of it is to modulate cholesterol homeostasis in the body.120 A correlation exists between the NPC1L1 level and HCV infection.66 Specific antibodies, especially ones that target the NPC1L1 large extracellular loop 1 (LEL1), effectively eradicate HCV entry in a manner similar to that of CD81 antibodies, indicating the potential action mode of this receptor.65 Ezetimibe is an FDA-approved NPC1L1 antagonist that is clinically used to treat hypercholesterolemia. The application of ezetimibe inhibits HCV entry and cell-to-cell transmission in vitro, while in vivo, this drug delays the establishment of genotype 1 HCV infections in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice with humanized hepatocytes (Table 1).66 The therapeutic window in humans has not yet been determined.

Clathrin-mediated viral endocytosis and membrane fusion

After interacting with a series of receptors, HC virions are internalized into cells via a highly coordinated process, most likely through clathrin-mediated endocytosis together with some cell entry factors, such as CD81 and CLDN1.70 The trafficking of the CD81–CLDN1 receptor complex promotes simultaneous virus internalization and fusion.60,104,106 During this process, the internalized vesicles form early and late endosomes, which are then prepared for the subsequent virion-cell fusion process.69 The use of either siRNA molecules targeting the clathrin heavy chain or the specific inhibitor chlorpromazine, which effectively interferes with clathrin-coated pit formation, impairs HCVpp entry and HCVcc infection in host cells (Table 1).67 Arbidol is an indole-derivative molecule that is licensed as an anti-influenza drug in China and Russia.121,122 This broad-spectrum antiviral uses several approaches to inhibit HCV cell entry. One of its antiviral mechanisms involves affecting clathrin-mediated endocytosis by impairing clathrin-coated pit release and dynamin-2-induced membrane scission (Table 1).68

Membrane fusion between the virus and host cell is the final step before the viral genome is released into the cytosol to start translation and replication.123 The envelope proteins are primed by virus–receptor interactions (most likely CD81) to become sensitive to low pH, and the fusogenic conformational changes of the related peptides are activated by the acidic environment and proper temperature of the endosomal lumen.71,90,124 Lipids, including cholesterol and sphingomyelin (SM), are essential components that facilitate HCV fusion.125,126 Studies have shown that the addition of cholesterol enhances the fusion efficiency of the HCV particle. Additionally, among virions of different densities, the lowest-density particle, HCVcc, exhibits the highest specific fusogenicity.127

HCV fusion inhibitors are basically characterized into the following three groups. The first group targets the acidification-triggering mechanism of virion–cell membrane fusion. Currently available acidification inhibitors include concanamycin A and bafilomycin A, two potent inhibitors of vacuolar ATPases (Table 1).69 Chloroquine and ammonium chloride are also considered to disturb endosome acidification and to suppress the occurrence of membrane fusion in a dose-dependent manner (Table 1).70,71 The second group focuses on the lipid compositions of both virus and host cells, which are indispensable throughout the process of virus fusion. In addition to its inhibitory effect on viral endocytosis, the indole-derivative arbidol also inhibits HCV membrane fusion, most likely via a dual-binding mode that involves aromatic residues in viral glycoproteins and phospholipids at the membrane–water interface, thus impeding the required conformational changes of fusion peptides during virus fusion (Table 1).72 Phenothiazines are small-molecule compounds containing nitrogen and sulfur tricyclic structures. Recently, three phenothiazine compounds have been identified as potent HCV entry inhibitors (Table 1); they suppress virion–cell membrane fusion by incorporating into target membranes and increase the fluidity of cholesterol-rich membranes, destabilizing the pre-fusion state of the virus.73 Rigid amphipathic fusion inhibitors (RAFIs) are a class of synthetic rigid amphiphiles that are similar to phospholipids. RAFIs can interact with envelope lipids and increase the activation barrier of viral proteins, leading to the blockage of increased negative curvature during the initial viral fusion stage (Table 1).74 AUY11 is a representative arabino-based RAFI.75 LJ001 is a small-molecule compound that specifically intercalates into viral membranes to inactivate the virion from a pre-fusion state, thereby blocking virus fusion (Table 1).76 Silymarin is a compound mixture of several flavonolignans and flavonoid taxifolins; it inhibits HCV infection both in vitro and in vivo in a similar pattern to that of arbidol (Table 1).77,78 The third group of fusion inhibitors includes several compounds with unclear mechanisms, including ferroquine, a chloroquine analog, and phosphorothioate oligonucleotides (PS-ONs), which act as amphipathic DNA polymers.79,80 PS-ONs inhibit HCV infection both in vitro and in vivo, possibly at the fusion step (Table 1).

Some natural, plant-derived compounds, such as the flavonoid ladanein, the terpenoids saikosaponin, oleanolic acid, tannic acid or gallic acid, or the small molecule SKI-1/SIP inhibitor PF-429242, have antiviral activities against HCV during an early stage of viral infection (Table 1).81,82,83,84,85,86 However, their exact antiviral mechanisms and potential applications in clinical practice require further investigation and evaluation.

Moreover, several FDA-approved drugs that have already been qualified for clinical application have shown antiviral activities against HCV infection. Chlorcyclizine HCl (CCZ) is an over-the-counter anti-histamine drug for allergy symptoms. CCZ blocks late-stage of HCV entry before viral replication and is now undergoing a phase Ib clinical trial.87 Sorafenib is a multi-kinase inhibitor that has been approved for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma.128 A recent study shows that sorafenib inhibits both HCV entry and production and affects CLDN1 expression and localization.88 Aspirin, a commonly used analgesic and anti-platelet drug, blocks HCV entry by downregulating CLDN1 (Table 1).89 These drugs are relatively accessible and affordable agents with an established clinical safety profile, thereby becoming promising candidates for drug repurposing for the treatment HCV infection.

Conclusions and perspectives

The unveiling of the molecular mechanisms of HCV entry in recent years has largely promoted the development of entry inhibitors targeting different stages of the early viral life cycle. Because viral entry is essential for the initiation, spread, and maintenance of HCV infection, great potential and numerous prospects exist for entry inhibitors to be applied as members of cocktail therapy in future HCV treatments. Although newly identified entry inhibitors have emerged continuously in recent years, most of them still remain in the in vitro stages of testing. Until now, only a few have entered clinical trials, including the most advanced entry inhibitor, ITX5061, which targets the host entry factor SRB1 to interfere with virus infection. This compound is currently undergoing phase II clinical trials and appears to be a promising option for future combination therapy.9,56,63 Regardless of its outcome, ITX5061 provides a good example for the study and development of entry inhibitors. Moreover, several compounds with favorable anti-HCV potencies have already been approved to treat other diseases in the clinic and provide a good method of screening for novel entry inhibitors of HCV. Table 1 summarizes the targets and developmental stages of current antiviral agents during the HCV entry process.

Unlike the currently marketed anti-HCV DAAs, which target viral proteins of high variability, most entry inhibitors are HTAs with high genetic barriers, which are valuable features for avoiding viral escape, due to their conserved nature. Because all of the major HCV genotypes are believed to enter host cells via the same cellular pathways, the antiviral activities of most entry inhibitors tend to be genotype-independent.129 Moreover, entry inhibitors are also bestowed with the unique advantage of preventing cell-to-cell transmission as long as their antiviral targets cover common factors in both cell-free and cell-to-cell viral spread.130 Additionally, such drugs will help end-stage HCV patients resist graft reinfection after undergoing liver transplantation. A series of novel antiviral agents is currently being tested in in vitro assays or in vivo animal models. Some of these agents have entered the clinical stage for evaluation in patients. The satisfactory outcomes of this class of entry inhibitors should complement current treatment approaches and lead to more efficient, economical and better tolerated options for HCV patients, especially difficult-to-treat patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National S&T Major Project for Infectious Diseases Control (2012ZX10002003-004-010), Natural Science Foundation of China (81171564, 81273557, 81302812 and 81221061), Medical Youth Science Program (13QNP100), and Shanghai Municipal Natural Science Foundation (13ZR1449300).

References

- 1Lavanchy D. The global burden of hepatitis C. Liver Int 2009; 29: 74–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2Alter MJ. Epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 2436–2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3Ghany MG, Strader DB, Thomas DL, Seeff LB, American Association for the Study of Liver D. Diagnosis, management, and treatment of hepatitis C: an update. Hepatology 2009; 49: 1335–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4Liang TJ, Ghany MG. Current and future therapies for hepatitis C virus infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 1907–1917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5Mederacke I, Von Hahn T. Survival of the fittest: selection of hepatitis C virus variants during liver graft reinfection. Hepatology 2011; 53: 705–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6Buhler S, Bartenschlager R. New targets for antiviral therapy of chronic hepatitis C. Liver Int 2012; 32: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7Aghemo A, De Francesco R. New horizons in hepatitis C antiviral therapy with direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology 2013; 58: 428–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8Gane EJ, Stedman CA, Hyland RH et al. Nucleotide polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for hepatitis C. N Engl J Med 2013; 368: 34–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9Issur M, Gotte M. Resistance patterns associated with HCV NS5A inhibitors provide limited insight into drug binding. Viruses 2014; 6: 4227–4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10Alqahtani SA, Afdhal N, Zeuzem S et al. Safety and tolerability of ledipasvir/sofosbuvir with and without ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection: analysis of phase III ION trials. Hepatology 2015; 62: 25–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11Klibanov OM, Gale SE, Santevecchi B. Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir and dasabuvir tablets for hepatitis C virus genotype 1 infection. Ann Pharmacother 2015; 49: 566–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12Deeks ED. Ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir plus dasabuvir: a review in chronic HCV genotype 1 infection. Drugs 2015; 75: 1027–1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13A 4-drug combination (Viekira Pak) for hepatitis C. JAMA. 2015; 313: 1857–1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. Holkira (ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir with dasabuvir) and harvoni (ledipasvir/sofosbuvir) for chronic hepatitis C: a review of the clinical evidence. Ottawa: CADTH, 2015. Available at https://www.cadth.ca/sites/default/files/pdf/htis/jan-2015/RC0632%20Holkira%20and%20Harvoni%20Final.pdf (accessed 16 Jan 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 15Keating GM. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir: a review of its use in chronic hepatitis C. Drugs 2015; 75: 675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16Temesgen Z, Rizza SA. Daclatasvir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Drugs Today (Barc) 2015; 51: 277–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17Kowdley KV, Lawitz E, Crespo I et al. Sofosbuvir with pegylated interferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for treatment-naive patients with hepatitis C genotype-1 infection (ATOMIC): an open-label, randomised, multicentre phase 2 trial. Lancet 2013; 381: 2100–2107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18Lawitz E, Lalezari JP, Hassanein T et al. Sofosbuvir in combination with peginterferon alfa-2a and ribavirin for non-cirrhotic, treatment-naive patients with genotypes 1, 2, and 3 hepatitis C infection: a randomised, double-blind, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13: 401–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19Sarrazin C, Hezode C, Zeuzem S, Pawlotsky JM. Antiviral strategies in hepatitis C virus infection. J Hepatol 2012; 56: S88–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20Barth H, Schafer C, Adah MI et al. Cellular binding of hepatitis C virus envelope glycoprotein E2 requires cell surface heparan sulfate. J Biol Chem 2003; 278: 41003–41012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21Barth H, Schnober EK, Zhang F et al. Viral and cellular determinants of the hepatitis C virus envelope-heparan sulfate interaction. J Virol 2006; 80: 10579–10590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22Jiang J, Cun W, Wu X, Shi Q, Tang H, Luo G. Hepatitis C virus attachment mediated by apolipoprotein E binding to cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol 2012; 86: 7256–7267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23Molina S, Castet V, Fournier-Wirth C et al. The low-density lipoprotein receptor plays a role in the infection of primary human hepatocytes by hepatitis C virus. J Hepatol 2007; 46: 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24Albecka A, Belouzard S, Op de Beeck A et al. Role of low-density lipoprotein receptor in the hepatitis C virus life cycle. Hepatology 2012; 55: 998–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25Syed GH, Tang H, Khan M, Hassanein T, Liu J, Siddiqui A. Hepatitis C virus stimulates low-density lipoprotein receptor expression to facilitate viral propagation. J Virol 2014; 88: 2519–2529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26Helle F, Wychowski C, Vu-Dac N, Gustafson KR, Voisset C, Dubuisson J. Cyanovirin-N inhibits hepatitis C virus entry by binding to envelope protein glycans. J Biol Chem 2006; 281: 25177–25183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27Khanal M, Barras A, Vausselin T et al. Boronic acid-modified lipid nanocapsules: a novel platform for the highly efficient inhibition of hepatitis C viral entry. Nanoscale 2015; 7: 1392–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28Holmskov U, Thiel S, Jensenius JC. Collections and ficolins: humoral lectins of the innate immune defense. Annu Rev Immunol 2003; 21: 547–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29Hamed MR, Brown RJ, Zothner C et al. Recombinant human L-ficolin directly neutralizes hepatitis C virus entry. J Innate Immun 2014; 6: 676–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30Ciesek S, von Hahn T, Colpitts CC et al. The green tea polyphenol, epigallocatechin-3-gallate, inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology 2011; 54: 1947–1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31Calland N, Albecka A, Belouzard S et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin-3-gallate is a new inhibitor of hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology 2012; 55: 720–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32Calland N, Sahuc ME, Belouzard S et al. Polyphenols inhibit hepatitis C virus entry by a new mechanism of action. J Virol 2015; 89: 10053–10063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33Redwan EM, Uversky VN, El-Fakharany EM, Al-Mehdar H. Potential lactoferrin activity against pathogenic viruses. C R Biol 2014; 337: 581–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34El-Fakharany EM, Sanchez L, Al-Mehdar HA, Redwan EM. Effectiveness of human, camel, bovine and sheep lactoferrin on the hepatitis C virus cellular infectivity: comparison study. Virol J 2013; 10: 199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35Redwan EM, El-Fakharany EM, Uversky VN, Linjawi MH. Screening the anti infectivity potentials of native N- and C-lobes derived from the camel lactoferrin against hepatitis C virus. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014; 14: 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36Hong W, Lang Y, Li T et al. A p7 ion channel-derived peptide inhibits hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. J Biol Chem 2015; 290: 23254–23263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37VanCompernolle SE, Wiznycia AV, Rush JR, Dhanasekaran M, Baures PW, Todd SC. Small molecule inhibition of hepatitis C virus E2 binding to CD81. Virology 2003; 314: 371–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38Brimacombe CL, Grove J, Meredith LW et al. Neutralizing antibody-resistant hepatitis C virus cell-to-cell transmission. J Virol 2011; 85: 596–605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39Lavillette D, Tarr AW, Voisset C et al. Characterization of host-range and cell entry properties of the major genotypes and subtypes of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2005; 41: 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40Gottwein JM, Scheel TK, Jensen TB et al. Development and characterization of hepatitis C virus genotype 1–7 cell culture systems: role of CD81 and scavenger receptor class B type I and effect of antiviral drugs. Hepatology 2009; 49: 364–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41Vanwolleghem T, Bukh J, Meuleman P et al. Polyclonal immunoglobulins from a chronic hepatitis C virus patient protect human liver-chimeric mice from infection with a homologous hepatitis C virus strain. Hepatology 2008; 47: 1846–1855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42Meuleman P, Hesselgesser J, Paulson M et al. Anti-CD81 antibodies can prevent a hepatitis C virus infection in vivo. Hepatology 2008; 48: 1761–1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43Ji C, Liu Y, Pamulapati C et al. Prevention of hepatitis C virus infection and spread in human liver chimeric mice by an anti-CD81 monoclonal antibody. Hepatology 2015; 61: 1136–1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44Molina S, Castet V, Pichard-Garcia L et al. Serum-derived hepatitis C virus infection of primary human hepatocytes is tetraspanin CD81 dependent. J Virol 2008; 82: 569–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45Hsu M, Zhang J, Flint M et al. Hepatitis C virus glycoproteins mediate pH-dependent cell entry of pseudotyped retroviral particles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 7271–7276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46Wakita T, Pietschmann T, Kato T et al. Production of infectious hepatitis C virus in tissue culture from a cloned viral genome. Nat Med 2005; 11: 791–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47Zhong J, Gastaminza P, Cheng G et al. Robust hepatitis C virus infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102: 9294–9299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48Kapadia SB, Barth H, Baumert T, McKeating JA, Chisari FV. Initiation of hepatitis C virus infection is dependent on cholesterol and cooperativity between CD81 and scavenger receptor B type I. J Virol 2007; 81: 374–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49Cai Z, Cai L, Jiang J, Chang KS, van der Westhuyzen DR, Luo G. Human serum amyloid A protein inhibits hepatitis C virus entry into cells. J Virol 2007; 81: 6128–6133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50Lavie M, Voisset C, Vu-Dac N et al. Serum amyloid A has antiviral activity against hepatitis C virus by inhibiting virus entry in a cell culture system. Hepatology 2006; 44: 1626–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51Zeisel MB, Koutsoudakis G, Schnober EK et al. Scavenger receptor class B type I is a key host factor for hepatitis C virus infection required for an entry step closely linked to CD81. Hepatology 2007; 46: 1722–1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52Bartosch B, Verney G, Dreux M et al. An interplay between hypervariable region 1 of the hepatitis C virus E2 glycoprotein, the scavenger receptor BI, and high-density lipoprotein promotes both enhancement of infection and protection against neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 2005; 79: 8217–8229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53Catanese MT, Graziani R, von Hahn T et al. High-avidity monoclonal antibodies against the human scavenger class B type I receptor efficiently block hepatitis C virus infection in the presence of high-density lipoprotein. J Virol 2007; 81: 8063–8071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54Lacek K, Vercauteren K, Grzyb K et al. Novel human SR-BI antibodies prevent infection and dissemination of HCV in vitro and in humanized mice. J Hepatol 2012; 57: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55Masson D, Koseki M, Ishibashi M et al. Increased HDL cholesterol and apoA-I in humans and mice treated with a novel SR-BI inhibitor. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2009; 29: 2054–2060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56Syder AJ, Lee H, Zeisel MB et al. Small molecule scavenger receptor BI antagonists are potent HCV entry inhibitors. J Hepatol 2011; 54: 48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57Zhu H, Wong-Staal F, Lee H et al. Evaluation of ITX 5061, a scavenger receptor B1 antagonist: resistance selection and activity in combination with other hepatitis C virus antivirals. J Infect Dis 2012; 205: 656–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58Sulkowski MS, Kang M, Matining R et al. Safety and antiviral activity of the HCV entry inhibitor ITX5061 in treatment-naive HCV-infected adults: a randomized, double-blind, phase 1b study. J Infect Dis 2014; 209: 658–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59Si Y, Liu S, Liu X et al. A human claudin-1-derived peptide inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. Hepatology 2012; 56: 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60Krieger SE, Zeisel MB, Davis C et al. Inhibition of hepatitis C virus infection by anti-claudin-1 antibodies is mediated by neutralization of E2-CD81-claudin-1 associations. Hepatology 2010; 51: 1144–1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61Fofana I, Krieger SE, Grunert F et al. Monoclonal anti-claudin 1 antibodies prevent hepatitis C virus infection of primary human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 953–964, 964 e951–954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62Mailly L, Xiao F, Lupberger J et al. Clearance of persistent hepatitis C virus infection in humanized mice using a claudin-1-targeting monoclonal antibody. Nat Biotechnol 2015; 5: 549–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63Lupberger J, Zeisel MB, Xiao F et al. EGFR and EphA2 are host factors for hepatitis C virus entry and possible targets for antiviral therapy. Nat Med 2011; 17: 589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64Martin DN, Uprichard SL. Identification of transferrin receptor 1 as a hepatitis C virus entry factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 10777–10782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65Del Campo JA, Rojas A, Romero-Gomez M. Entry of hepatitis C virus into the cell: a therapeutic target. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18: 4481–4485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66Sainz BJr, Barretto N, Martin DN et al. Identification of the Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 cholesterol absorption receptor as a new hepatitis C virus entry factor. Nat Med 2012; 18: 281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67Blanchard AA, Watson PH, Shiu RP et al. Differential expression of claudin 1, 3, and 4 during normal mammary gland development in the mouse. DNA Cell Biol 2006; 25: 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68Blaising J, Levy PL, Polyak SJ, Stanifer M, Boulant S, Pecheur EI. Arbidol inhibits viral entry by interfering with clathrin-dependent trafficking. Antiviral Res 2013; 100: 215–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69Meertens L, Bertaux C, Dragic T. Hepatitis C virus entry requires a critical postinternalization step and delivery to early endosomes via clathrin-coated vesicles. J Virol 2006; 80: 11571–11578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70Blanchard E, Belouzard S, Goueslain L et al. Hepatitis C virus entry depends on clathrin-mediated endocytosis. J Virol 2006; 80: 6964–6972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71Tscherne DM, Jones CT, Evans MJ, Lindenbach BD, McKeating JA, Rice CM. Time- and temperature-dependent activation of hepatitis C virus for low-pH-triggered entry. J Virol 2006; 80: 1734–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72Boriskin YS, Leneva IA, Pecheur EI, Polyak SJ. Arbidol: a broad-spectrum antiviral compound that blocks viral fusion. Curr Med Chem 2008; 15: 997–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73Chamoun-Emanuelli AM, Pecheur EI, Simeon RL, Huang D, Cremer PS, Chen Z. Phenothiazines inhibit hepatitis C virus entry, likely by increasing the fluidity of cholesterol-rich membranes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2013; 57: 2571–2581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74St Vincent MR, Colpitts CC, Ustinov AV et al. Rigid amphipathic fusion inhibitors, small molecule antiviral compounds against enveloped viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 17339–17344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75Colpitts CC, Ustinov AV, Epand RF, Epand RM, Korshun VA, Schang LM. 5-(Perylen-3-yl)ethynyl-arabino-uridine (aUY11), an arabino-based rigid amphipathic fusion inhibitor, targets virion envelope lipids to inhibit fusion of influenza virus, hepatitis C virus, and other enveloped viruses. J Virol 2013; 87: 3640–3654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76Wolf MC, Freiberg AN, Zhang T et al. A broad-spectrum antiviral targeting entry of enveloped viruses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 3157–3162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77Polyak SJ, Morishima C, Shuhart MC, Wang CC, Liu Y, Lee DY. Inhibition of T-cell inflammatory cytokines, hepatocyte NF-κB signaling, and HCV infection by standardized Silymarin. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 1925–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78Wagoner J, Negash A, Kane OJ et al. Multiple effects of silymarin on the hepatitis C virus lifecycle. Hepatology 2010; 51: 1912–1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79Vausselin T, Calland N, Belouzard S et al. The antimalarial ferroquine is an inhibitor of hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2013; 58: 86–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80Matsumura T, Hu Z, Kato T et al. Amphipathic DNA polymers inhibit hepatitis C virus infection by blocking viral entry. Gastroenterology 2009; 137: 673–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81Haid S, Novodomska A, Gentzsch J et al. A plant-derived flavonoid inhibits entry of all HCV genotypes into human hepatocytes. Gastroenterology 2012; 143: 213–222 e215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82Lin LT, Chung CY, Hsu WC et al. Saikosaponin b2 is a naturally occurring terpenoid that efficiently inhibits hepatitis C virus entry. J Hepatol 2015; 62: 541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83Yu F, Wang Q, Zhang Z et al. Development of oleanane-type triterpenes as a new class of HCV entry inhibitors. J Med Chem 2013; 56: 4300–4319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84Blanchet M, Sureau C, Guevin C, Seidah NG, Labonte P. SKI-1/S1P inhibitor PF-429242 impairs the onset of HCV infection. Antiviral Res 2015; 115: 94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85Liu S, Chen R, Hagedorn CH. Tannic acid inhibits hepatitis C virus entry into Huh7.5 Cells. PloS One 2015; 10: e0131358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86Hsu WC, Chang SP, Lin LC et al. Limonium sinense and gallic acid suppress hepatitis C virus infection by blocking early viral entry. Antiviral Res 2015; 118: 139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87He S, Lin B, Chu V et al. Repurposing of the antihistamine chlorcyclizine and related compounds for treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Sci Transl Med 2015; 7: 282–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88Descamps V, Helle F, Louandre C et al. The kinase-inhibitor sorafenib inhibits multiple steps of the hepatitis C virus infectious cycle in vitro. Antiviral Res 2015; 118: 93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89Yin P, Zhang L. Aspirin inhibits hepatitis C virus entry by downregulating claudin-1. J Viral Hepat 2015. Aug 20. doi: 10.1111/jvh.12446. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 90Koutsoudakis G, Kaul A, Steinmann E et al. Characterization of the early steps of hepatitis C virus infection by using luciferase reporter viruses. J Virol 2006; 80: 5308–5320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91Khan N, Mukhtar H. Tea polyphenols for health promotion. Life Sci 2007; 81: 519–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92Halegoua-De Marzio D, Kraft WK, Daskalakis C, Ying X, Hawke RL, Navarro VJ. Limited sampling estimates of epigallocatechin gallate exposures in cirrhotic and noncirrhotic patients with hepatitis C after single oral doses of green tea extract. Clin Ther 2012; 34: 2279–2285 e2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93Garcia-Montoya IA, Cendon TS, Arevalo-Gallegos S, Rascon-Cruz Q. Lactoferrin a multiple bioactive protein: an overview. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1820: 226–236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94Gentzsch J, Brohm C, Steinmann E et al. Hepatitis C virus p7 is critical for capsid assembly and envelopment. PLoS Pathog 2013; 9: e1003355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95Steinmann E, Pietschmann T. Hepatitis C virus p7-a viroporin crucial for virus assembly and an emerging target for antiviral therapy. Viruses 2010; 2: 2078–2095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96Oren R, Takahashi S, Doss C, Levy R, Levy S. TAPA-1, the target of an antiproliferative antibody, defines a new family of transmembrane proteins. Mol Cell Biol 1990; 10: 4007–4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97Levy S, Shoham T. The tetraspanin web modulates immune-signalling complexes. Nat Rev Immunol 2005; 5: 136–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98Boucheix C, Rubinstein E. Tetraspanins. Cell Mol Life Sci 2001; 58: 1189–1205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99Baugh JM, Garcia-Rivera JA, Gallay PA. Host-targeting agents in the treatment of hepatitis C: a beginning and an end? Antiviral Res 2013; 100: 555–561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100Perrault M, Pecheur EI. The hepatitis C virus and its hepatic environment: a toxic but finely tuned partnership. Biochem J 2009; 423: 303–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101Catanese MT, Ansuini H, Graziani R et al. Role of scavenger receptor class B type I in hepatitis C virus entry: kinetics and molecular determinants. J Virol 2010; 84: 34–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102Baranova IN, Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV et al. Serum amyloid A binding to CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1) mediates serum amyloid A protein-induced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 8031–8040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103Cai L, de Beer MC, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR. Serum amyloid A is a ligand for scavenger receptor class B type I and inhibits high density lipoprotein binding and selective lipid uptake. J Biol Chem 2005; 280: 2954–2961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104Farquhar MJ, Hu K, Harris HJ et al. Hepatitis C virus induces CD81 and claudin-1 endocytosis. J Virol 2012; 86: 4305–4316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105Harris HJ, Farquhar MJ, Mee CJ et al. CD81 and claudin 1 coreceptor association: role in hepatitis C virus entry. J Virol 2008; 82: 5007–5020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106Harris HJ, Davis C, Mullins JG et al. Claudin association with CD81 defines hepatitis C virus entry. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 21092–21102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107Evans MJ, von Hahn T, Tscherne DM et al. Claudin-1 is a hepatitis C virus co-receptor required for a late step in entry. Nature 2007; 446: 801–805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108Furuse M, Fujita K, Hiiragi T, Fujimoto K, Tsukita S. Claudin-1 and -2: novel integral membrane proteins localizing at tight junctions with no sequence similarity to occludin. J Cell Biol 1998; 141: 1539–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109Haid S, Grethe C, Dill MT, Heim M, Kaderali L, Pietschmann T. Isolate-dependent use of claudins for cell entry by hepatitis C virus. Hepatology 2014; 59: 24–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110Ploss A, Evans MJ, Gaysinskaya VA et al. Human occludin is a hepatitis C virus entry factor required for infection of mouse cells. Nature 2009; 457: 882–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Robbins JB et al. A genetically humanized mouse model for hepatitis C virus infection. Nature 2011; 474: 208–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112Dorner M, Horwitz JA, Donovan BM et al. Completion of the entire hepatitis C virus life cycle in genetically humanized mice. Nature 2013; 501: 237–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113Sendi H, Mehrab-Mohseni M, Foureau DM et al. MiR-122 decreases HCV entry into hepatocytes through binding to the 3' UTR of OCLN mRNA. Liver Int 2015; 35: 1315–1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114Diao J, Pantua H, Ngu H et al. Hepatitis C virus induces epidermal growth factor receptor activation via CD81 binding for viral internalization and entry. J Virol 2012; 86: 10935–10949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115Fujita N, Horiike S, Sugimoto R et al. Hepatic oxidative DNA damage correlates with iron overload in chronic hepatitis C patients. Free Radic Biol Med 2007; 42: 353–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116Fujita N, Sugimoto R, Urawa N et al. Hepatic iron accumulation is associated with disease progression and resistance to interferon/ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007; 22: 1886–1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117Kaito M. Molecular mechanism of iron metabolism and overload in chronic hepatitis C. J Gastroenterol 2007; 42: 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118Yu L. The structure and function of Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 protein. Curr Opin Lipidol 2008; 19: 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119Altmann SW, Davis HRJr, Zhu LJ et al. Niemann-Pick C1 like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science 2004; 303: 1201–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120Jia L, Betters JL, Yu L. Niemann-pick C1-like 1 (NPC1L1) protein in intestinal and hepatic cholesterol transport. Annu Rev Physiol 2011; 73: 239–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121Brooks MJ, Burtseva EI, Ellery PJ et al. Antiviral activity of arbidol, a broad-spectrum drug for use against respiratory viruses, varies according to test conditions. J Med Virol 2012; 84: 170–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122Delogu I, Pastorino B, Baronti C, Nougairede A, Bonnet E, de Lamballerie X. In vitro antiviral activity of arbidol against Chikungunya virus and characteristics of a selected resistant mutant. Antiviral Res 2011; 90: 99–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123Harrison SC. Viral membrane fusion. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2008; 15: 690–698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124Sharma NR, Mateu G, Dreux M, Grakoui A, Cosset FL, Melikyan GB. Hepatitis C virus is primed by CD81 protein for low pH-dependent fusion. J Biol Chem 2011; 286: 30361–30376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125Pecheur EI, Diaz O, Molle J et al. Morphological characterization and fusion properties of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins obtained from cells transduced with hepatitis C virus glycoproteins. J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 25802–25811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126Haid S, Pietschmann T, Pecheur EI. Low pH-dependent hepatitis C virus membrane fusion depends on E2 integrity, target lipid composition, and density of virus particles. J Biol Chem 2009; 284: 17657–17667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127Blaising J, Pecheur EI. Lipids: a key for hepatitis C virus entry and a potential target for antiviral strategies. Biochimie 2013; 95: 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128Wilhelm S, Carter C, Lynch M et al. Discovery and development of sorafenib: a multikinase inhibitor for treating cancer. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2006; 5: 835–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129Fofana I, Jilg N, Chung RT, Baumert TF. Entry inhibitors and future treatment of hepatitis C. Antiviral Res 2014; 104: 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130Zeisel MB, Fofana I, Fafi-Kremer S, Baumert TF. Hepatitis C virus entry into hepatocytes: molecular mechanisms and targets for antiviral therapies. J Hepatol 2011; 54: 566–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]