Abstract

Objectives

To explore utilisation patterns of asthma medication before, during and after pregnancy as recorded in seven European population-based databases.

Design

A descriptive drug utilisation study.

Setting

7 electronic healthcare databases in Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands, Italy (Emilia Romagna and Tuscany), Wales, and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink representing the rest of the UK.

Participants

All women with a pregnancy ending in a delivery that started and ended between 2004 and 2010, who had been present in the database for the year before, throughout and the year following pregnancy.

Main outcome measures

The percentage of deliveries where the woman received an asthma medicine prescription, based on prescriptions issued (UK) or dispensed (non-UK), during the year before, throughout or during the year following pregnancy. Asthma medicine prescribing patterns were described for 3-month time periods and the choice of asthma medicine and changes in prescribing over the study period were evaluated in each database.

Results

In total, 1 165 435 deliveries were identified. The prevalence of asthma medication prescribing during pregnancy was highest in the UK and Wales databases (9.4% (CI95 9.3% to 9.6%) and 9.4% (CI95 9.1% to 9.6%), respectively) and lowest in the Norwegian database (3.7% (CI95 3.7% to 3.8%)). In the year before pregnancy, the prevalence of asthma medication prescribing remained constant in all regions. Prescribing levels peaked during the second trimester of pregnancy and were at their lowest during the 3-month period following delivery. A decline was observed, in all regions except the UK, in the prescribing of long-acting β-2-agonists during pregnancy. During the 7-year study period, there were only small changes in prescribing patterns.

Conclusions

Differences were found in the prevalence of prescribing of asthma medications during and surrounding pregnancy in Europe. Inhaled β-2 agonists and inhaled corticosteroids were, however, the most popular therapeutic regimens in all databases.

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study captured over 1.1 million pregnancies from seven regions of Europe.

Over 65 000 deliveries were included where the woman received a prescription for an asthma medication during pregnancy.

Prescription data were recorded independently by the prescriber or dispensing pharmacist, removing maternal recall bias.

In many people, the symptoms of asthma are intermittent. While the date of prescribing or dispensing is accurate, this is not necessarily entirely consistent with the date of medicine use, particularly with short-acting β-2-agonists prescribed for symptom relief.

An absence of data on indication for prescribing was a limitation when investigating the use of oral glucocorticoids to treat more severe asthma, as these products can be prescribed to treat a number of other conditions, including inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis.

Introduction

Asthma is a common chronic respiratory disease and maternal asthma, particularly poorly controlled asthma, has been associated with a number of adverse maternal and pregnancy outcomes, including pre-eclampsia, low birth weight, small for gestational age and preterm delivery.1 2 To achieve good disease control and normal lung function, women who are pregnant or considering becoming pregnant are generally recommended to continue taking their asthma medications, as the maternal and fetal risks associated with uncontrolled asthma are greater than the risks from using asthma medications.3 4 Some studies have demonstrated an increased risk of specific major congenital malformations following first trimester exposure to asthma medications, but at present there is a degree of uncertainty surrounding the effects of treatment versus the effects of the disease itself.5–8 Asthma is initially managed with short-acting β-2-agonists (SABAs) for symptom relief in the case of reasonably well-controlled disease and with a step-up approach when disease control becomes reduced, with the addition of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) and other medications to prevent and reduce inflammation of the airways.3 4 Studies evaluating the course of asthma symptoms during pregnancy have shown that approximately one-third of women find their symptoms improve, one-third get worse and one-third remain the same.9 10

The prevalence of asthma during pregnancy in Europe has been estimated at between 4% and 8%,10–12 making it one of the most common, potentially serious, medical complications in pregnancy.13 Estimates of asthma prevalence during pregnancy vary by geographic location, study setting, definition of asthma and time period.10 11 14–16 The overall prevalence of prescribed antiasthma therapy during pregnancy has been reported for the UK,10 Sweden,17 Norway18 and the Netherlands,16 but for many other regions of Europe it is unknown and few studies have looked at the prevalence of prescribing of individual classes of asthma medicine. This study aimed to describe the extent and nature of asthma medication prescribing, during pregnancy and in the year before and after pregnancy, between 2004 and 2010, using data from population-based electronic healthcare databases in Europe. This study forms part of EUROmediCAT, a Seventh Framework Programme study funded by the European Commission that aims to make more systematic use of electronic healthcare databases in combination with the EUROCAT congenital anomaly registry data19 for reproductive safety evaluation.

Methods

Setting

Seven population-based electronic healthcare databases, which captured data on prescriptions and pregnancies, contributed to the study; two in Italy (Tuscany20/Emilia Romagna21), two in the UK (the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank in Wales22 23 and the UK-wide Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)24 with data from Wales excluded), and one each in Denmark,25–27 the Netherlands28 and Norway29 30 (see online supplementary table S1). A more detailed description of the databases can be found elsewhere.31 Where multiple databases were linked, such as in Denmark, where data from the Danish National Patient Register were linked to the Danish Prescription Registry, for the remainder of this paper these linked databases will be referred to as a single database.

Data extraction

A common protocol was implemented across databases. All pregnancies were identified that started and ended between 1 January 2004 and 31 December 2010 (except for Denmark and Norway where inclusion dates were 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2009 and 1 January 2005 to 31 December 2010, respectively). Pregnancies were eligible for the study if they ended in a delivery (live or stillbirth) and the woman had been contributing data to the database capturing prescription data, throughout pregnancy and for a full year before the start of pregnancy and following delivery. Women were able to contribute more than one pregnancy to the study. For each eligible delivery, a best estimate of the first day of the last menstrual period was calculated as summarised in online supplementary table S1.

All prescriptions for an asthma medication recorded in the databases during the study period were identified. In the UK databases, this included prescriptions issued and in the non-UK databases this included only prescriptions actually dispensed. None of the databases captured asthma medications given directly to the patient during a hospital stay. In Denmark, Norway and the Netherlands, all asthma medication dispensed from a pharmacy was captured, regardless of who prescribed the medication and where the prescription was made. In the UK databases, prescriptions initiated by a specialist in a hospital outpatient department and private prescriptions were rarely recorded; these numbers were likely to be small as most subsequent repeat prescribing will have been undertaken in primary care and private practice is limited. In Italy, only prescriptions reimbursed by the Italian healthcare system were captured; this included all reimbursed prescriptions regardless of whether they were prescribed by a general practitioner (GP) or a specialist who was an employee of the healthcare system. Asthma medications identified within the databases included all SABA, long-acting β-2-agonists (LABAs), ICS, combined β-2-agonists and inhaled steroids in a fixed-dose combination, leukotriene receptor antagonists, cromoglicate and related therapy, antimuscarinic bronchodilators and theophylline. These were defined as products with an Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification code starting R03. Prescriptions for oral glucocorticoids (ATC code H02AB), potentially used to treat an asthma exacerbation, were also identified. Since oral glucocorticoids can be prescribed for conditions other than asthma, only those prescribed in a 3-month time period during which an asthma medication was also prescribed were eligible for inclusion.

Analyses

The percentage of pregnancies where the women received a prescription for an asthma medication in each of the databases was calculated for the year leading up to pregnancy, during pregnancy and the year following pregnancy. Prescribing patterns were described for each pregnancy trimester and for 3-month time periods during the years before and after pregnancy. For each class of asthma medication, the specific products most frequently prescribed were compared between regions. Changes in prescribing over calendar time were also described and compared. Sensitivity analyses were carried out restricting the analyses to those deliveries where the woman received a minimum of two prescriptions for an asthma medicine during the 33-month time period of interest.

Results

Within the seven databases, 1 165 435 deliveries were identified (table 1). The mean maternal age at the start of pregnancy was highest in Emilia Romagna and lowest in Wales (32.3 and 27.7 years, respectively) (table 1). The mean maternal age in all of the regions did not vary substantially between those who received and those who did not receive a prescription for an asthma medicine. The prevalence of asthma medication prescribing during pregnancy was highest in the UK and Wales databases (9.4% (CI95 9.3% to 9.6%) and 9.4% (CI95 9.1% to 9.6%), respectively) and lowest in the Norwegian database (3.7% (CI95 3.7% to 3.8%)).

Table 1.

Percentage of deliveries between 2004 and 2010 where the woman received ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication in the year before pregnancy, during pregnancy or the year following pregnancy

| An asthma medication prescription during |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eligible deliveries in entire cohort | Mean maternal age at pregnancy start for entire cohort | One year before pregnancy |

Any of the pregnancy trimesters |

One year following pregnancy |

||||||||

| Country/region | N | Years | SD* | N | Per cent | (95% CI) | N | Per cent | (95% CI) | N | Per cent | (95% CI) |

| Denmark† | 320 846 | 30.0 | (4.9) | 16 722 | 5.2 | (5.1 to 5.3) | 13 988 | 4.4 | (4.3 to 4.4) | 14 067 | 4.4 | (4.3 to 4.5) |

| Italy—Tuscany | 157 916 | 31.8 | (4.9) | 13 240 | 8.4 | (8.3 to 8.5) | 8400 | 5.3 | (5.2 to 5.4) | 12 462 | 7.9 | (7.8 to 8.0) |

| Italy—Emilia Romagna | 129 220 | 32.3 | (4.9) | 16 317 | 12.7 | (12.5 to 12.9) | 10 804 | 8.4 | (8.3 to 8.6) | 15 030 | 11.7 | (11.5 to 11.9) |

| Norway‡ | 301 820 | 29.7 | (5.1) | 14 540 | 4.8 | (4.7 to 4.9) | 11 205 | 3.7 | (3.7 to 3.8) | 10 627 | 3.5 | (3.5 to 3.6) |

| The Netherlands | 14 607 | 30.2 | (4.8) | 937 | 6.4 | (6.0 to 6.8) | 738 | 5.1 | (4.7 to 5.4) | 848 | 5.8 | (5.4 to 6.2) |

| UK* | 182 920 | 30.2 | (6.1) | 17 646 | 9.7 | (9.5 to 9.8) | 17 264 | 9.4 | (9.3 to 9.6) | 16 913 | 9.3 | (9.1 to 9.4) |

| Wales | 58 106 | 27.7 | (6.1) | 5801 | 10.0 | (9.7 to 10.2) | 5450 | 9.4 | (9.1 to 9.6) | 5335 | 9.2 | (9.0 to 9.4) |

| Total across countries | 1 165 435 | 85 203 | 67 849 | 75 282 | ||||||||

*Excluding Wales to avoid duplication of pregnancies in the Welsh Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank.

†2004–2009.

‡2005–2010.

SD, standard deviation.

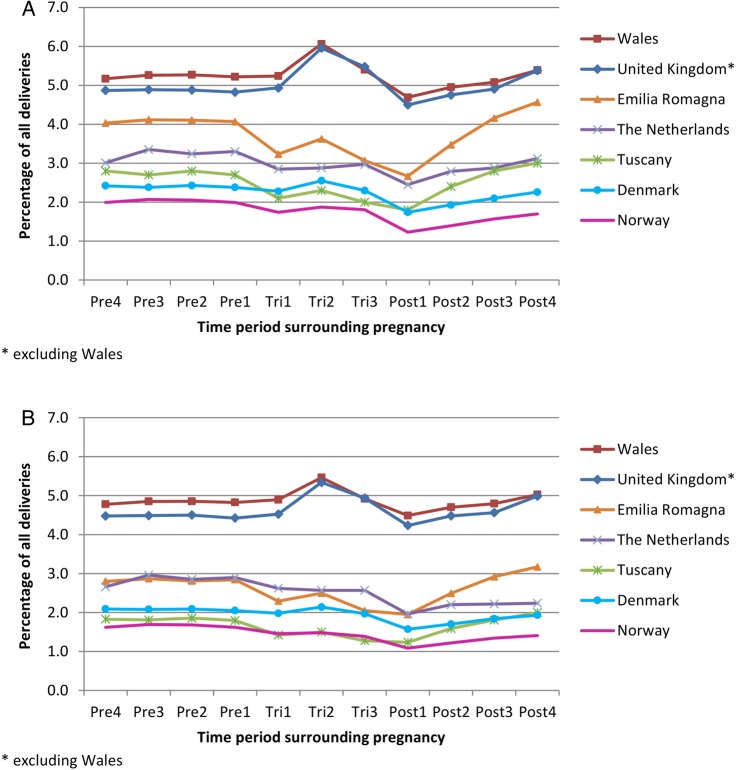

During the year before pregnancy, the prevalence of asthma medication prescribing was relatively constant in all regions (figure 1A). In Italy and Norway, a reduction in prescribing was observed during the first trimester of pregnancy. During pregnancy, prescribing levels peaked during the second trimester with the largest increases being observed in the UK/Wales. Prescribing was at its lowest during the 3-month period following delivery and then gradually increased, returning towards prepregnancy levels, during the remainder of the year following delivery. Of those who received a prescription for an asthma medication in the year before, during and/or the year after pregnancy, approximately 30% in the Netherlands, Wales and the rest of the UK received only a single prescription during this 33-month time period; in Denmark, it was 39%, Norway 45% and in Emilia Romagna it was as high as 50%. Table 2 and figure 1B show the prevalence of asthma medication prescribing in each of the regions restricted to pregnancies where the woman was issued/dispensed at least two prescriptions for an asthma medicine during the 33-month time period. Inhaled SABAs and ICS were the products most commonly prescribed to women who received only a single prescription (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of asthma medication prescribing in women with a delivery, between 2004 and 2010, where the woman received (A) ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication during ≥1 of the time periods of interest and (B) ≥2 prescriptions for an asthma medication during the entire time period of interest.

Table 2.

Percentage of deliveries between 2004 and 2010 restricted to women who received ≥2 prescriptions for an asthma medication in the year before pregnancy, during pregnancy or the year following pregnancy

| An asthma medication prescription during |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of eligible deliveries in entire cohort | Mean maternal age at pregnancy start for entire cohort | One year before pregnancy |

Any of the pregnancy trimesters |

One year following pregnancy |

||||||||

| Country/region | N | Years | SD* | N | Per cent | (95% CI) | N | Per cent | (95% CI) | N | Per cent | (95% CI) |

| Denmark† | 320 846 | 30.0 | (4.9) | 12 593 | 3.9 | (3.9 to 4.0) | 10 650 | 3.3 | (3.3 to 3.4) | 10 900 | 3.4 | (3.3 to 3.5) |

| Italy—Tuscany | 157 916 | 31.8 | (4.9) | 7551 | 4.8 | (4.7 to 4.9) | 4930 | 3.1 | (3.0 to 3.2) | 7113 | 4.5 | (4.4 to 4.6) |

| Italy—Emilia Romagna | 128 429 | 32.3 | (4.9) | 9895 | 7.7 | (7.6 to 7.9) | 6831 | 5.3 | (5.2 to 5.4) | 9453 | 7.4 | (7.2 to 7.5) |

| Norway‡ | 301 820 | 29.7 | (5.1) | 10 016 | 3.3 | (3.3 to 3.4) | 7908 | 2.6 | (2.6 to 2.7) | 8080 | 2.7 | (2.6 to 2.7) |

| The Netherlands | 14 607 | 30.2 | (4.8) | 751 | 4.9 | (4.6 to 5.2) | 601 | 4.1 | (3.8 to 4.4) | 538 | 3.7 | (3.4 to 4.0) |

| UK* | 182 920 | 30.2 | (6.1) | 14 773 | 8.1 | (8.0 to 8.2) | 14 402 | 7.9 | (7.8 to 8.0) | 14 582 | 8.0 | (7.8 to 8.3) |

| Wales | 58 106 | 27.7 | (6.1) | 4858 | 8.4 | (8.1 to 8.6) | 4617 | 8.0 | (7.7 to 8.2) | 4683 | 8.1 | (3.3 to 3.5) |

| Total across countries | 1 165 435 | |||||||||||

*Excluding Wales to avoid duplication of pregnancies in the Welsh Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank.

†2004–2009.

‡2005–2010.

SD, standard deviation.

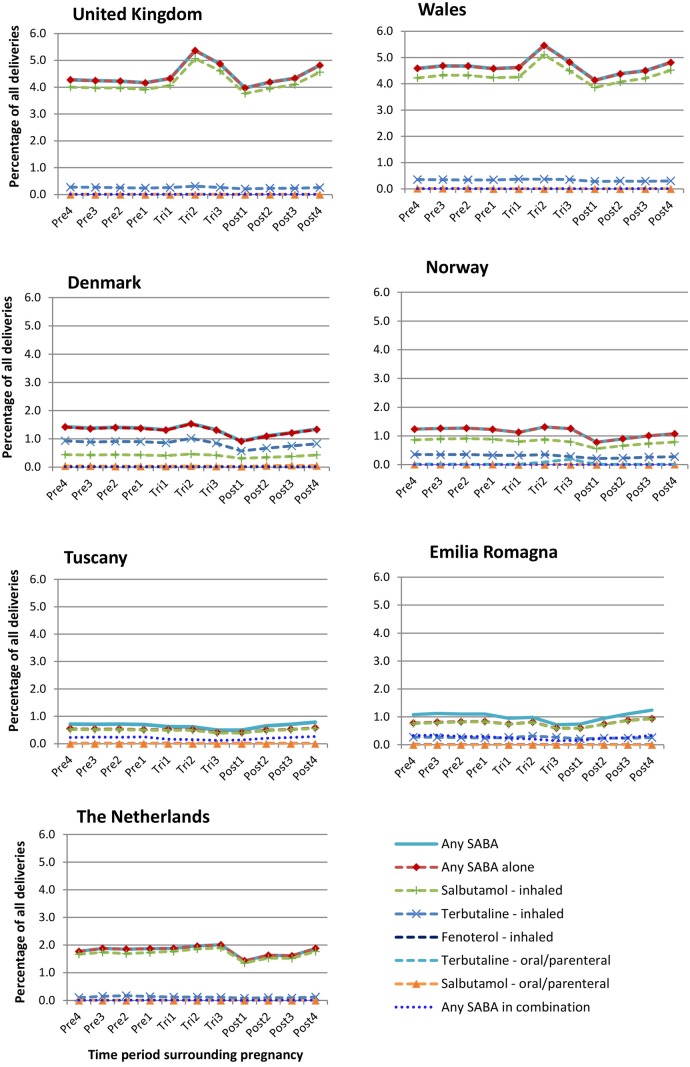

The prescribing prevalence of SABAs in each of the 3-month time periods was lowest in Tuscany and highest in the UK databases (figure 2). In the UK, approximately 90% of women who received a prescription for an asthma medication during pregnancy received a prescription for a SABA, whereas in Denmark and Norway it was approximately 75% and in Italy it was 26%. These percentages were not dissimilar to those during the year before pregnancy. In all regions, with the exception of Denmark where terbutaline was the most popular, salbutamol accounted for the majority of SABA prescriptions (figure 2). SABAs in a fixed-dose combination with an ICS were rarely prescribed in all regions, with the Italian databases having the highest prescribing prevalence. In the UK, the SABA prescribing prevalence increased during the second trimester of pregnancy and was approximately 25% higher than during the first trimester.

Figure 2.

Prevalence of prescribing of short-acting β-2-agonists (SABAs) in the year before, during and after pregnancy in women with a live or stillbirth during 2004–2010 for women prescribed ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication during ≥1 of the time periods of interest.

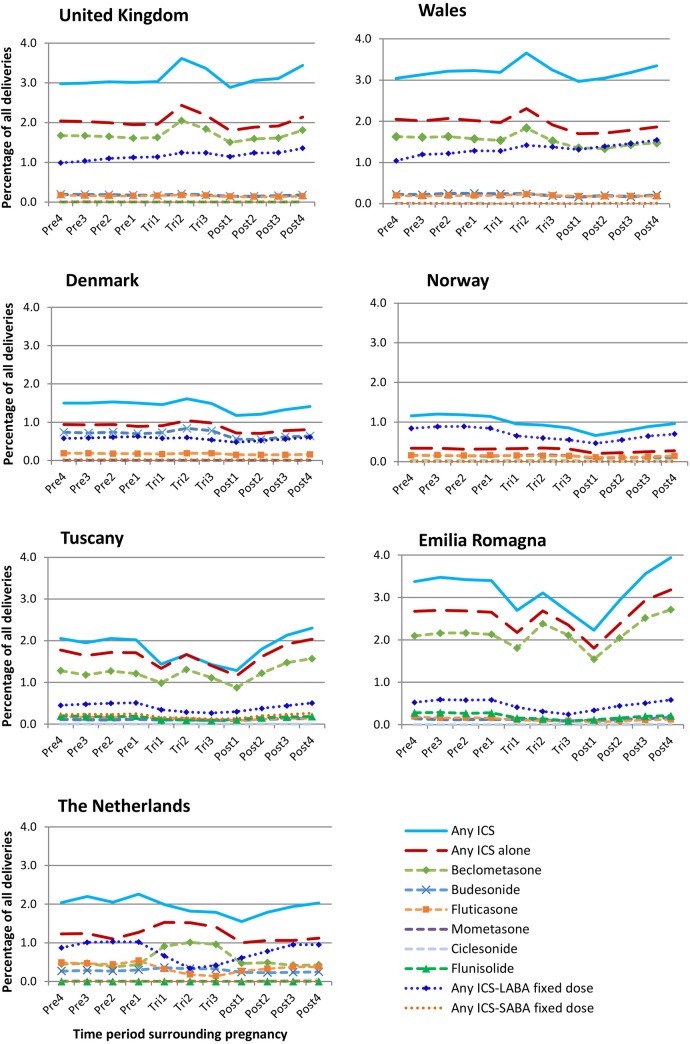

Norway had the lowest prescribing prevalence of ICS and the UK had the highest (figure 3). Of women who received a prescription for an asthma medication during one of the pregnancy trimesters, approximately 50% in Norway, 60% in the UK and Denmark and 89% in Emilia Romagna received a prescription for an ICS during pregnancy. Italy was the only region where prescribing of ICSs was more common than the prescribing of SABAs. In the UK/Wales and Italian databases, beclometasone was the most commonly prescribed ICS, whereas in Denmark it was budesonide and in Norway beclometasone and budesonide were equally prescribed (figure 3). In the Netherlands, the prevalence of beclometasone prescribing during pregnancy was almost double the prevalence observed before and after pregnancy, with the increase coinciding with a reduction in the prescribing of fluticasone and other ICS in a fixed-dose combination with a LABA. Norway was the only region where the prevalence of prescribing of ICS in a fixed-dose combination with a LABA was higher than the prescribing of ICS products not as part of a fixed-dose combination.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of prescribing of ICS in the year before, during and after pregnancy in women with a live or stillbirth during 2004–2010 for women prescribed ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication during ≥1 of the time periods of interest (ICS, inhaled corticosteroid; LABA, long-acting β-2-agonist; SABA, short-acting β-2-agonist).

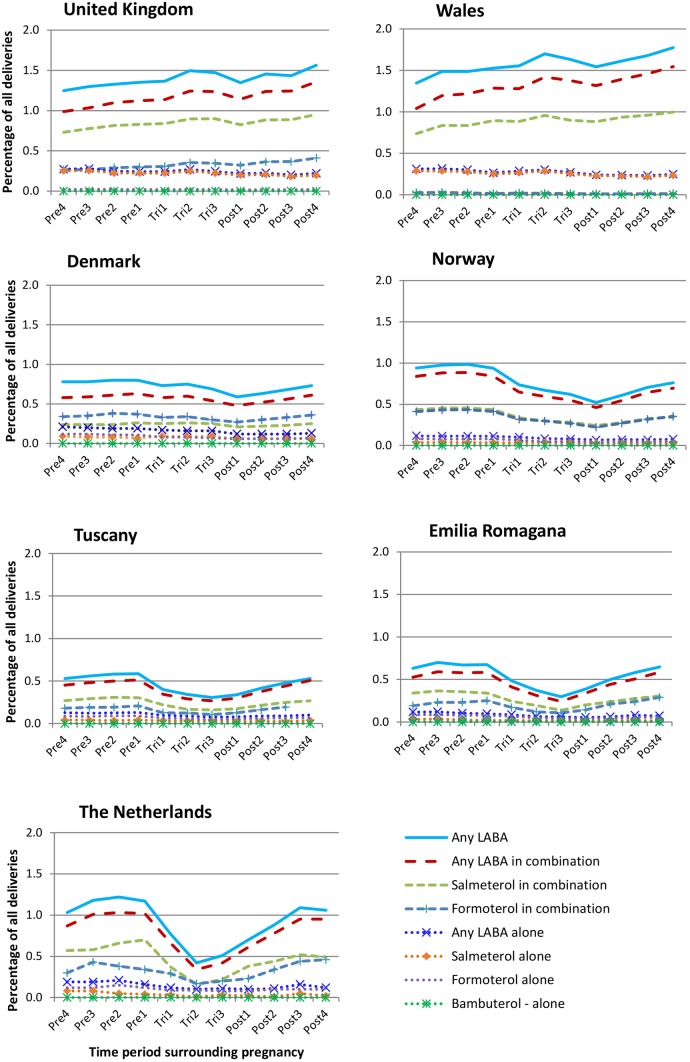

During pregnancy, evidence of a reduction in the prescribing of LABAs, both alone and as part of a fixed-dose combination, was observed in Norway, the Netherlands and Italy (figure 4). In Norway and Italy, prescribing was approximately 50% lower during the second trimester of pregnancy compared with the 3-month period prior to the start of pregnancy; in the Netherlands, it was approximately 65% lower. Of those who received a prescription for a LABA during pregnancy, between 75.2% in Tuscany and 86.5% in Norway received it in a fixed-dose combination with an ICS. Salmeterol in a fixed-dose combination was the most commonly prescribed LABA product in the UK, Italy and the Netherlands, while in Denmark it was formoterol in combination with an ICS and in Norway both formoterol and salmeterol in fixed-dose combinations were prescribed to the same degree. This was not substantially different from the therapeutic pattern observed in non-pregnant women during prepregnancy.

Figure 4.

Prevalence of prescribing of long-acting β-2-agonists (LABAs) in the year before, during and after pregnancy in women with a live or stillbirth during 2004–2010 for women prescribed ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication during ≥1 of the time periods of interest.

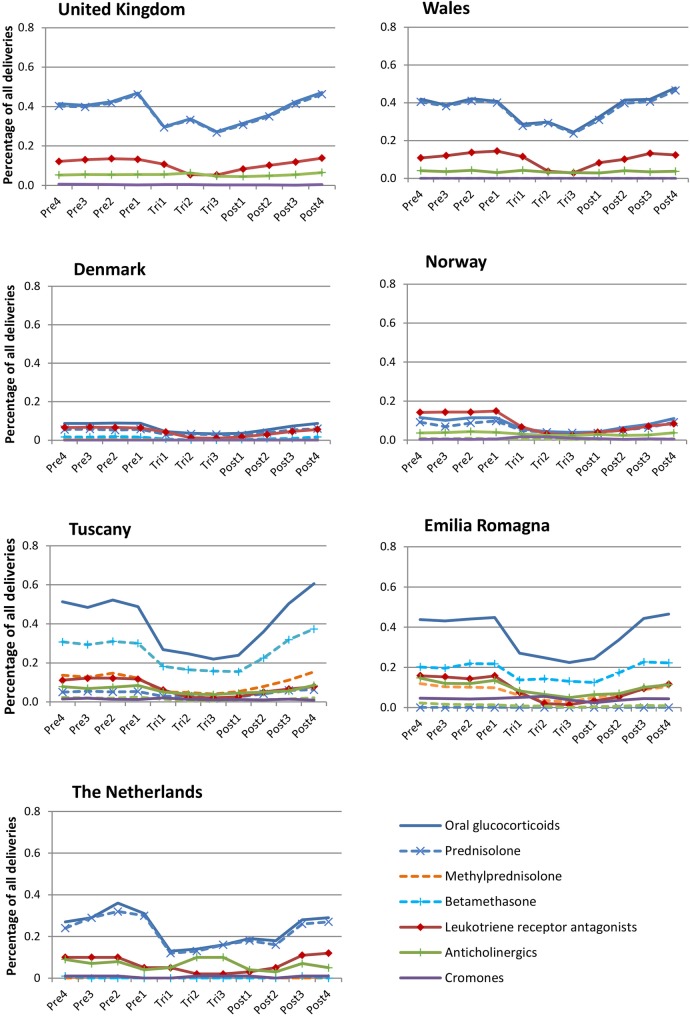

The prescribing of other asthma medications was low in all regions and lowest in Denmark and Norway (figure 5). Cromones were rarely prescribed, although the number of women receiving a prescription in Norway increased to 51 during the first trimester of pregnancy compared with 17 during the 3-month period before pregnancy. The percentage of deliveries where the mother received a prescription for a leukotriene receptor antagonist during pregnancy ranged from 0.04% (CI95 0.03% to 0.04%) in Norway to 0.14% (CI95 0.11% to 0.17%) in Wales, with all regions showing a decline in prescribing during the latter trimesters. No prescriptions for an anticholinergic were dispensed during the time period of interest in Denmark and the highest level of prescribing of these during pregnancy was observed in the Netherlands, with 0.16% (CI95 0.10% to 0.23%) of women receiving a prescription. Prescribing of oral glucocorticoids was considerably higher in the UK and Italy than other regions, although in all databases the levels of prescribing declined during pregnancy and increased steadily in the year following delivery. Prednisolone was the most commonly prescribed oral corticosteroid in all regions.

Figure 5.

Prevalence of prescribing of other asthma medications in the year before, during and after pregnancy in women with a live or stillbirth during 2004–2010 for women prescribed ≥1 prescription for an asthma medication during ≥1 of the time periods of interest.

During the 7-year study period, there were only small changes in prescribing patterns. In Denmark, Norway and the UK, the prescribing prevalence of LABAs in a fixed-dose combination with an ICS during pregnancy was found to increase (0.7–1.1%, 1.1–1.3% and 1.1–1.9%, respectively) while the prescribing of LABAs not in a fixed-dose combination was found to decline. In the UK, a small decline in the prescribing of ICS not in combination with a β-agonist was observed between 2004 and 2009 (from 4.5% (CI95 4.2% to 4.7%) to 3.8% (CI95 3.6% to 4.0%) of all pregnancies), while in Denmark there was evidence of a small decline in SABA prescribing.

Discussion

Main findings

This study found variations in the prevalence of asthma medication prescribing and the specific products most commonly prescribed to women before, during and after pregnancy in different regions of Europe. Changes in prescribing were observed during pregnancy, with a peak in prescribing in the second trimester, after which prescribing declined until 4–6 months after delivery. The prescribing of asthma medications was considerably higher in the UK/Wales and Emilia Romagna than in other regions; for the UK/Wales, the differences may be accentuated because these databases captured all prescriptions issued, while the other databases captured only those actually dispensed.

Strengths and limitations

This study captured over 65 000 deliveries, between 2004 and 2010, where the woman received a prescription for an asthma medication during her pregnancy. Prescription information was recorded independently by the prescriber or pharmacist, removing maternal recall bias. No data, however, were available on whether the women took the medication and whether it was administered as instructed. The often intermittent nature of asthma symptoms and the fact that some treatments can be used on an ‘as needed’ basis makes determining the precise timing of exposure difficult in electronic healthcare databases. In the UK databases, data were based on prescriptions issued, whereas in other regions it was prescriptions dispensed. It is possible that some women who are issued prescriptions may not get them dispensed. However, even if we take a conservative estimate and assume that 25% of prescriptions issued in the UK databases were not dispensed, the levels of asthma prescribing during pregnancy would still be higher in the UK/Wales than in all other regions, with the exception of Emilia Romagna. This study did not account for prescriptions issued during one 3-month time period that could have continued to be taken during the following 3-month time period. This will have resulted in an underestimation of exposure during some time periods, especially as women may use inhalers for a long time after they are prescribed. Some women may also have several inhalers for a product issued in a single prescription and women may have multiple inhalers of the same product in use at the same time. The study period for which data were available did vary between databases and it is possible that these small differences in calendar time may have influenced the results and could explain some of the variations observed; however, for those countries contributing data for the entire study period, only small changes in prescribing patterns by calendar time were observed.

An absence of data on indication for prescribing was a limitation when investigating the use of oral glucocorticoids to treat more severe asthma and asthma exacerbation, as these products can be prescribed to treat a number of other conditions. This study attempted to reduce the impact of this by only including oral glucocorticoid prescriptions if they were issued during the same 3-month period as an asthma medication; it is likely, however, that some misclassification will still have occurred. In addition, some women will not have needed to take the oral glucocorticoids at the time of issue but will have been prescribed them in advance so that they had them available for when they experienced an exacerbation in the future. None of the databases captured prescriptions issued during a hospital stay or a visit to an accident and emergency department and this may have led to an underestimate of the use of oral glucocorticoids to treat asthma exacerbations. An absence of data on the indication for prescribing of medications was also a limitation when trying to interpret and provide explanations for the differences observed in prescribing practices. The large percentage of women receiving only a single prescription in some regions may imply that some products may be being prescribed for bronchoconstriction in association with acute bronchitis or other respiratory tract infections. Inhaled SABAs and ICS were the products most commonly prescribed to women who received only a single prescription and in these cases they are unlikely to have been for a chronic condition. It is also possible that some women are started on an inhaled SABA or ICS to see if it has any effect on the symptoms and if there is no effect, the treatment is discontinued and it is concluded that the woman was not suffering from asthma.

Comparison with the literature

The UK prescribing prevalence of asthma medications during pregnancy in this study was found to be slightly higher than that reported by a previous study looking at the prevalence of treated asthma using data from the CPRD (9.4% vs 8.3%).10 The previous study had required women to have evidence of an asthma diagnosis in addition to at least one prescription or a minimum of six prescriptions to be eligible for inclusion in the study, and this is likely to explain some of the difference observed. Trends and levels of overall asthma medication prescribing in the Netherlands and Norway were in line with those reported elsewhere for studies looking at a similar time period and using the same data sources (5.1% vs 4.5% during pregnancy in the Netherlands and 1.7% vs 1.7% during the first trimester in Norway).16 18 The Norwegian study, however, had not reported on the prescribing prevalence during the entire pregnancy and on the level of prescribing of specific classes of asthma medications. In Denmark, a large cohort study based on maternal self-reporting, rather than prescription data, had reported that 6.2% of women suffered from asthma during pregnancy between 1996 and 2002, which was higher than the 4.4% (CI95 4.3% to 4.4%) who had received a prescription during the slightly later time period of our study.11 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report on the prevalence of asthma medication prescribing during pregnancy in Italy.

Interpretation

The variation observed in the levels of prescribing may to some extent reflect differences in the prevalence of asthma in the different regions. The World Health Survey conducted by the WHO has reported country-specific estimates of doctor diagnosed asthma prevalence, at any time, in individuals aged 18–44 years. This study found a considerably lower prevalence of asthma in Italy (6.0%) compared with the other regions in our study: 9.5% in Denmark, 11.1% in Norway, 15.2% in the Netherlands and 17.6% in the UK.32 Variations may also be explained by differences in exposure to allergens, infections, air pollution and climate, as well as the cost of individual medications and different attitudes to prescribing. Unfortunately, data on these variables were not available within the majority of databases and could not be evaluated as part of this study. Variations in prevalence and these variables may also explain the within-country regional prescribing differences observed between the two Italian databases, with the Italian National Survey data33 demonstrating geographic variation in asthma prevalence (5.3% vs 8.4% in Tuscany vs Emilia Romagna, respectively). Hospital admission data for asthma exacerbations in Italy support our findings, with higher hospital admissions observed in Emilia Romagna than Tuscany,34 as well as higher costs associated with the diagnostic label ‘bronchitis (asthmatic)/asthma’.35 The differences in prescribing prevalence between Tuscany and Emilia Romagna and the representativeness of the two regions do not permit the extrapolation of the results to the rest of Italy. The findings of our study also demonstrated a peak in asthma medication prescribing during the second trimester in all regions. This may be explained by the findings of a systematic review that concluded that a worsening of asthma symptoms is most likely during the latter trimesters with a peak in the sixth month of gestation and an improvement during the last 4 weeks of pregnancy,36 which may also explain some of the lower levels of prescribing observed shortly after pregnancy. It is also possible that women are informed of the importance of well controlled asthma when visiting their GP during their pregnancy, and they are therefore more likely to request and use the required prescriptions during the second trimester than they were during the early stages of pregnancy. Women may also, to some extent, feel more reassured about taking their asthma medicines once the critical period of organogenesis during the first trimester of pregnancy has passed.

In all regions, the prescribing guidelines advised that treatment for asthma during pregnancy should be the same as that for other groups of patients and that the risks associated with poorly controlled asthma were greater than those posed by conventional asthma medications.4 37–41 There was general agreement that SABAs were not teratogenic, with salbutamol and terbutaline being the recommended first choice. In Italy, however, the possibility of increased risks of maternal and neonatal transitory hypoglycaemia, maternal and fetal tachycardia, acute heart failure, pulmonary oedema and maternal death were listed in relation to salbutamol and the guidelines stated that the manufacture advised to avoid during pregnancy unless the potential benefit outweighs the risk.37 The advice from the manufacturer and the risk of a number of maternal and fetal outcomes were not reported in the guidelines of the other regions, and it is possible that this may, in part, explain the lower levels of SABA prescribing in Italy than the other regions; these risks are, however, largely thought to be associated with medication when used as an infusion and not for inhaled medications used at a normal dose.

All guidelines advised that there was no need to stop ICS during pregnancy.4 37–39 41 During the study period, budesonide was the only ICS that had the more favourable Food and Drug Administration (FDA) pregnancy category B, while all others had an FDA pregnancy category C, indicative of the fact that animal reproduction studies had shown an adverse effect on the fetus and there were no adequate and well-controlled studies in humans.42 Norway41 and Italy37 were the only countries, however, where the guidelines recommended budesonide as the ICS of choice and Denmark39 was the only region where budesonide was found to be the ICS most commonly prescribed. In Italy, despite the guidelines recommending budesonide, beclometasone was by far the most commonly prescribed ICS. The Italian guidelines37 on beclometasone also stated that the manufacturer recommends avoiding its use during the first trimester; although a small reduction was observed during this time period, it was still quite commonly prescribed. It is possible that other factors, including the cost of different products, may influence prescribing practices in the different regions, but this study was not able to investigate this.

The UK guidelines were the only ones to specify that LABAs should be used with an ICS and ideally as part of a combination product.4 It was stated that although little information is available on the safety of combination products, there is no reason, in this instance, to think that the products would be more harmful in combination than when given separately. In the Danish guidelines, no concerns were raised about the use of LABAs,39 and the UK guidelines referenced evidence from prescription event monitoring to suggest that salmeterol was safe in pregnancy.4 In Norway, it was advised that the older and better known LABAs should be used before the newer ones and this study found salmeterol and formoterol to be the most popular and prescribed products in equal measures.41 In the Netherlands, the guidelines on LABAs differed from other regions, with the emphasis being put on the lack of information relating to their safety and guidance from the Dutch College of General Practitioners advising against the use of these medications in pregnancy.38 The differences in prescribing guidelines relating to LABAs are likely to explain some of the variations observed between regions. Our study observed a sharp decline in the prescribing of LABAs during pregnancy in the Netherlands, which is in line with the guidelines and has also been observed in a Dutch study by Zetstra-van der Woude et al.16 The decline in the prescribing of LABAs during pregnancy, observed in all regions except the UK, indicates that clinicians and pregnant women may worry about using these rather new inhaled medications during pregnancy, as there are currently few published studies reporting on their safety.

The limited information on the safety of leukotriene receptor antagonists was acknowledged within all guidelines, with a general consensus that they should not be started during pregnancy but could be continued in women who were using them to successfully control their asthma before pregnancy; all regions in our study saw some decline in the level of their prescribing during pregnancy. For oral glucocorticoids, several of the guidelines mentioned the possibility of an increased risk of cleft lip/palate if used during the first trimester of pregnancy, and our study observed a decline in their use during pregnancy in all regions. In Denmark, the UK and the Netherlands, it was stated that any well indicated treatment should be initiated and not withheld during pregnancy as the advantages of well controlled asthma would outweigh any associated risk to the fetus.4 38 39 In Denmark and the Netherlands, it was recommended that these were prescribed at the lowest dose and for the shortest time period. The low prescribing levels of oral asthma medications in general in all regions and the decline observed during pregnancy are reassuring, as treatment guidelines focus on inhaled medications and recommend the addition of oral products only for severe asthma.

Conclusion

This study identified differences in the percentage of women who received a prescription for an asthma medication during and surrounding pregnancy in different regions of Europe. Differences were also observed in relation to the specific products that were most commonly prescribed; however, no major differences were observed in the treatment in general with inhaled β-2 agonists and ICS being prescribed to the majority of women.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of the EUROmediCAT Steering Group and, most particularly, Professor Corinne de Vries for her invaluable contribution to the design of the study. They would also like to thank Professor Vibeke Backer from the Advisory Board for her comments on the draft manuscript. They would like to acknowledge Dr Sandra Baldacci for her comments on the Italian data and all the data providers who make anonymised data available for research. The work presented in this paper describes anonymised data held in the Secure Anonymised Information Linkage (SAIL) Databank, which is part of the national e-health records research infrastructure for Wales. They thank Karen Tingay and David Tucker for their contribution to the work carried out with SAIL data. This study also describes data from the Full Feature Clinical Practice Research Datalink obtained under licence from the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. The Tuscany Registry of Birth Defects is funded by the ‘‘Direzione Generale Diritti di cittadinanza e Coesione sociale—Regione Toscana.’’ The Emilia Romagna Registry of Birth Defects is funded by the Emilia Romagna Region Health authority grant number Delibera 56412/2010.

Footnotes

Contributors: LTWdJ-vdB and HD contributed to the conception of the study. RAC, SJ, APi, EG, AJN, KK and LTWdJ-vdB contributed to the design of the work. Data acquisition and analysis was carried out by AVH, EG and A-MNA, KK and AE, RG and APi, APu and AJN, HJB and LTWdJ-vdB, Karen Tingay, DT, SJ and RAC. RAC compiled the results for all regions. All the authors were involved in the interpretation of the study results as well as the drafting and revision of the manuscript and all approved the final version to be published.

Funding: This study was part of the EUROmediCAT research project (http://www.euromedicat.eu) which has been supported by the European Commission under the Seventh Framework Programme (grant agreement number 260598).

Disclaimer: The interpretation and conclusions contained in this report are those of the authors alone.

Competing interests: All authors, with the exception of A-MNA, RG, APu, AJN and AE, had financial support from the European Union for the submitted work under the Seventh Framework Programme (grant agreement HEALTH-F5-2011-260598). RAC owns shares in GlaxoSmithKline.

Ethics approval: Ethical and data access approvals were obtained for each database from the relevant governance infrastructures.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Murphy VE, Namazy JA, Powell H et al. . A meta-analysis of adverse perinatal outcomes in women with asthma. BJOG 2011;118:1314–23. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2011.03055.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Enriquez R, Griffin MR, Carroll KN et al. . Effect of maternal asthma and asthma control on pregnancy and perinatal outcomes. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;120:625–30. 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.05.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2014. (cited 09 May 2014). http://www.ginasthma.org/local/uploads/files/GINA_Report_2014.pdf

- 4.British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. British guideline on the management of asthma: a national clinical guideline. 2008. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign101.pdf

- 5.Lin S, Herdt-Losavio M, Gensburg L et al. . Maternal asthma, asthma medication use, and the risk of congenital heart defects. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2009;85:161–8. 10.1002/bdra.20523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin S, Munsie JPW, Herdt-Losavio ML et al. . Maternal asthma medication use and the risk of selected birth defects. Pediatrics 2012;129:e317–24. 10.1542/peds.2010-2660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Munsie JW, Lin S, Browne ML et al. . Maternal bronchodilator use and the risk of orofacial clefts. Hum Reprod 2011;26:3147–54. 10.1093/humrep/der315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garne E, Hansen AV, Morris J et al. . Use of asthma medication during pregnancy and risk of specific congenital anomalies: a European case-malformed control study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;136:1496–1502.e7. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.05.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juniper EF, Newhouse MT. Effect of pregnancy on asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis. In: Schatz M, Zeiger RS, Claman HN, eds. Asthma and immunological diseases in pregnancy and early infancy. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1993:223–50. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlton RA, Hutchison A, Davis KJ et al. . Asthma management in pregnancy. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e60247 10.1371/journal.pone.0060247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tegethoff M, Olsen J, Schaffner E et al. . Asthma during pregnancy and clinical outcomes in offspring: a national cohort study. Pediatrics 2013;132:483–91. 10.1542/peds.2012-3686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murphy VE, Gibson PG. Asthma in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med 2011;32:93–110. 10.1016/j.ccm.2010.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schatz M, Dombrowski MP, Wise R et al. . Asthma morbidity during pregnancy can be predicted by severity classification. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:283–8. 10.1067/mai.2003.1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kwon HL, Belanger K, Bracken MB. Asthma prevalence among pregnant and childbearing-aged women in the United States: estimates from National Health Surveys. Ann Epidemiol 2003;13:317–24. 10.1016/S1047-2797(03)00008-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louik C, Schatz M, Hernández-Díaz S et al. . Asthma in pregnancy and its pharmacologic treatment. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2010;105:110–7. 10.1016/j.anai.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zetstra-van der Woude AP, Vroegop JS, Bos H et al. . A population analysis of prescriptions for asthma medications during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013;131:711–17. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rejnö G, Lundholm C, Gong T et al. . Asthma during pregnancy in a population-based study—pregnancy complications and adverse perinatal outcomes. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e104755 10.1371/journal.pone.0104755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Engeland A, Bramness JG, Daltveit AK et al. . Prescription drug use among fathers and mothers before and during pregnancy. A population-based cohort study of 106,000 pregnancies in Norway 2004–2006. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2008;65:653–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03102.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dolk H. EUROCAT: 25 years of European surveillance of congenital anomalies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 2005;90:F355–8. 10.1136/adc.2004.062810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coloma PM, Trifirò G, Schuemie MJ et al. . Electronic healthcare databases for active drug safety surveillance: is there enough leverage? Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2012;21:611–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gagne JJ, Maio V, Berghella V et al. . Prescription drug use during pregnancy: a population-based study in Regione Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2008;64:1125–32. 10.1007/s00228-008-0546-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford D, Jones K, Verplancke J-P et al. . The SAIL Databank: building a national architecture for e-health research and evaluation. BMC Health Serv Res 2009;9:157 10.1186/1472-6963-9-157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyons R, Jones K, John G et al. . The SAIL Databank: linking multiple health and social care datasets. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2009;9:3 10.1186/1472-6947-9-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wood L, Martinez C. The general practice research database: role in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf 2004;27:871–81. 10.2165/00002018-200427120-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thygesen LC, Daasnes C, Thaulow I et al. . Introduction to Danish (nationwide) registers on health and social issues: structure, access, legislation, and archiving. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):12–16. 10.1177/1403494811399956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lynge E, Sandegaard JL, Rebolj M. The Danish National Patient Register. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):30–3. 10.1177/1403494811401482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wallach Kildemoes H, Toft Sørensen H, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health 2011;39(7 Suppl):38–41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Visser ST, Schuiling-Veninga CCM, Bos JHJ et al. . The population-based prescription database IADB.nl: its development, usefulness in outcomes research and challenges. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2013;13:285–92. 10.1586/erp.13.20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Espnes MG, Bjørge T, Engeland A. Comparison of recorded medication use in the Medical Birth Registry of Norway with prescribed medicines registered in the Norwegian Prescription Database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2011;20:243–8. 10.1002/pds.2085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Furu K, Wettermark B, Andersen M et al. . The Nordic countries as a cohort for pharmacoepidemiological research. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2010;106:86–94. 10.1111/j.1742-7843.2009.00494.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Charlton RA, Neville AJ, Jordan S et al. . Healthcare databases in Europe for studying medicine use and safety during pregnancy. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2014;23:586–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G et al. . Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional World Health Survey. BMC Public Health 2012;12:204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.National Statistics Institute. Multiscope statistical survey on families—aspects of daily life. 2013. http://siqual.istat.it/SIQual/visualizza.do?id=0058000 (accessed 19 Nov 2014).

- 34.Ministero della Salute (Ministry of Health). Direzione Generale della Programmazione sanitaria Ufficio VI (Directorate General for Health Planning Office VI). Elaborazione Banca Dati SDO (Database Hospital admission) 2012. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_1930_allegato.pdf (accessed 17 Nov 2014).

- 35.Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. The Use of Drugs in Italy Year 2013. http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/sites/default/files/Rapporto_OsMED_2013.pdf (accessed 13 Nov 2014).

- 36.Gluck JC, Gluck PA. The effect of pregnancy on the course of asthma. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am 2006;26:63–80. 10.1016/j.iac.2005.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco. Farmaciegravidanza. http://www.farmaciegravidanza.gov.it/ (accessed 13 Nov 2014).

- 38.Geijer RMM, Chavannes NH, Muris JWM et al. . NHG-Standaard Astma bij volwassenen (Tweede herziening). Huisarts Wet 2007;50:537–8. 10.1007/BF03085239 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lange P, Nielsen LP, Plaschke P. Astma hos gravide og ammende 2013. http://pro.medicin.dk/Sygdomme/Sygdom/318295#a000 (accessed 17 Nov 2014).

- 40.Working group for the guidelines on bronchial asthma in Tuscany. Guidelines on bronchial asthma—Tuscany Region—2014. http://www.snlg-iss.it/cms/files/LG_toscana_asma_2010.pdf (accessed 17 Nov 2014).

- 41.Norwegian Electronic Doctor's Guidelines (Norsk Elektronisk Legehåndbok). http://legehandboka.no (accessed 21 Oct 2014).

- 42.Gluck PA, Gluck JC. A review of pregnancy outcomes after exposure to orally inhaled or intranasal budesonide. Curr Med Res Opin 2005;21:1075–84. 10.1185/030079905X50570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]