Abstract

Objective

The aim of this study is to review highly cited articles that focus on non-publication of studies, and to develop a consistent and comprehensive approach to defining (non-) dissemination of research findings.

Setting

We performed a scoping review of definitions of the term ‘publication bias’ in highly cited publications.

Participants

Ideas and experiences of a core group of authors were collected in a draft document, which was complemented by the findings from our literature search.

Interventions

The draft document including findings from the literature search was circulated to an international group of experts and revised until no additional ideas emerged and consensus was reached.

Primary outcomes

We propose a new approach to the comprehensive conceptualisation of (non-) dissemination of research.

Secondary outcomes

Our ‘What, Who and Why?’ approach includes issues that need to be considered when disseminating research findings (What?), the different players who should assume responsibility during the various stages of conducting a clinical trial and disseminating clinical trial documents (Who?), and motivations that might lead the various players to disseminate findings selectively, thereby introducing bias in the dissemination process (Why?).

Conclusions

Our comprehensive framework of (non-) dissemination of research findings, based on the results of a scoping literature search and expert consensus will facilitate the development of future policies and guidelines regarding the multifaceted issue of selective publication, historically referred to as ‘publication bias’.

Keywords: MEDICAL ETHICS, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH, Publication Bias, OPEN Project, Dissemination bias

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We present a new comprehensive framework based on results from literature review and international expert consensus on (non-) dissemination of research results.

Our three step approach considers, for the first time, issues that need to be taken into account when disseminating research findings (What?), different players who should assume responsibility (Who?) and motivations that might lead to selective dissemination of research findings (Why?).

We only searched Web of Science, with the simple search term ‘publication bias’. This way, our literature search might have favoured older publications and systematic reviews of primary research.

Background

Systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials provide a valid summary of the available research findings, and are therefore crucial to evidence-based medical decision-making.1 It has long been recognised that identification of the entire relevant research evidence is essential to produce an unbiased and balanced summary, although non-dissemination of research findings may not necessarily lead to bias. For example, a journal publication may report on all prespecified outcomes and time points, but raw data may still be important for other researchers and research questions. This dissemination is not biased or selective, but, rather, a result of the current publication system. Nevertheless, ideally, all research conducted should be published and easily identifiable. Only under such circumstances can systematic reviews live up to their promise of providing unbiased, high-quality evidence for medical decision-making. However, it is not always possible to retrieve all eligible evidence for a given topic, as many studies never get published. The phenomenon of non-publication of studies based on the nature and direction of the results is often referred to as ‘publication bias’.2 3

Interpretations of research evidence can be distorted not only by the non-publication of an entire study—information may also be partially lacking or presented in a way that influences the take-up of the findings, such as selective reporting of outcomes or subgroups, or ‘data massaging’ (eg, the selective exclusion of patients from the analysis). Thus, over recent years, a new nomenclature for other types of bias related to the non-publication or distortion in the dissemination process of research findings has been developed, such as ‘reporting bias’,4 ‘time lag bias’,5 ‘location bias’,6 7 and many more. Nevertheless, all these different aspects are often still referred to as ‘publication bias’. Until now, no consensus on the definition of ‘publication bias’ has been reached in the literature.

Therefore, we aimed to perform a scoping review of highly cited articles that focus on non-publication of studies and to present the various definitions of biases related to the dissemination of research findings contained in the articles identified. Furthermore, we aimed to develop a comprehensive and consistent framework to defining (non-) dissemination of research findings in an international group of experts in the context of the OPEN Project (To Overcome failure to Publish nEgative fiNdings) based on the findings of our literature search.

Methods

A detailed protocol of our methods has been published.8 In brief, the following methods were used for literature search and the development of the ‘what, who and why?’ framework to defining (non-) dissemination of research findings.

Literature search

Search strategy

Our focus was on highly cited and publicly available articles in order to capture the most widely used definitions of ‘publication bias’. Therefore, we searched Web of Science9 on 19 November 2012. We used the simple search term ‘publication bias’, which had to be included in the title or abstract and also in the keywords. We chose Web of Science because it presents results of literature searches according to the total number of citations, therefore allowing us to identify the most frequently cited articles. Although we were interested in various aspects of problems in the dissemination process of research findings, we aimed at the identification of different definitions of ‘publication bias’ and thus decided that the term ‘publication bias’ should be part of all publications of interest. No language restrictions were applied. We did not search any other database or any grey literature.

Eligibility criteria

We included the 50 most frequently cited articles that focused on biases related to the non-publication or distortion in the dissemination process of research findings from any source and addressed to any audience. Since we were interested in the most common definitions of ‘publication bias’, we believed that 50 articles would provide enough information. We did not exclude self-citations, because we were interested in the absolute number of citations independent of the people who cited the work. In order to be included, articles needed to use the term ‘publication bias’ and provide some form of definition of it. We included only full-text articles.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts of search results. If a title or abstract could not be rejected with certainty by both reviewers, the full text of the paper was retrieved and assessed for eligibility. Any disagreement among reviewers was resolved by discussion and consensus or, if needed, by third party arbitration.

Data extraction

A specially designed data extraction form was developed and pilot-tested. KFM and DB independently extracted all relevant information from each eligible article. The following information was collected:

General characteristics (eg, author names, language and year of publication, journal)

Number of citations in Web of Science and rank

Definitions of biases related to the dissemination of research findings

Any disagreement was resolved by discussion and consensus or, if needed, arbitration by a third reviewer.

Data analysis and reporting

Data synthesis involved a descriptive summary of the range of definitions given to describe various forms of biases related to the dissemination of research findings.

Development of the OPEN framework of (non-) dissemination of research findings

We performed a scoping review of definitions of the term ‘publication bias’ in highly cited publications. In a second step, we proposed a draft regarding the issues that need to be considered when exploring possible biases due to selective dissemination of research findings capturing the ideas and experiences of the core group of authors. We then circulated the draft to all the co-authors and, in a third step, to all members of the OPEN consortium (an international group of experts). Experts reviewed the draft and provided feedback, as required, regarding the issues we identified, or contributed other insights. We continued this process until no additional ideas emerged. There have been three rounds of feedback: In the first round, 8 of 10 authors commented, in the second round, 5 of 10 authors commented and, in the last round, 9 of 10 authors commented.

At the end of this process, we reached consensus regarding the issues that need to be considered when exploring possible biases due to selective dissemination of research findings. Based on this consensus, targeted measures to reduce dissemination bias can be developed and implemented.

Results

Review of existing definitions of ‘publication bias’

We included the 50 most highly cited articles that provided a definition of ‘publication bias’ (see online supplementary file 1: included articles). Further information about the included articles is given in online supplementary file 2: General characteristics of included articles.

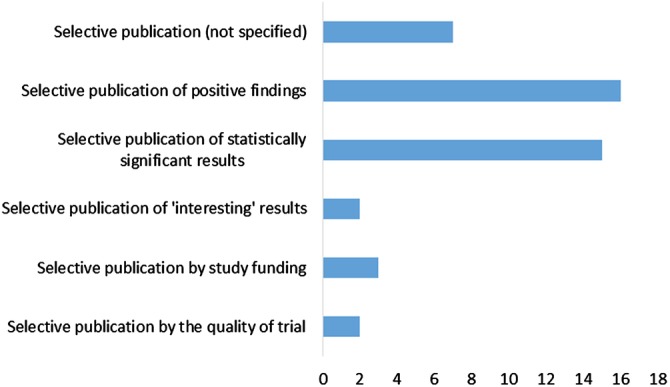

Most of the articles (38/50 articles) defined ‘publication bias’ as a form of selective publication, for various reasons (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Various reasons for selective publication.

Five of the 50 included articles argued that ‘publication bias’ as a term is not appropriate and that the authors prefer to call this phenomenon ‘submitting/editing bias’.

OPEN framework of (non-) dissemination of research findings

We suggest that the traditionally used term ‘publication bias’ is too limited as it does not include all the various problems that can occur in the process of disseminating research findings. We therefore propose to use the term ‘dissemination bias’ rather than ‘publication bias’, as suggested by others,10 11 because it captures various other problems that can occur throughout the entire process, from the planning and conduct of studies to the dissemination of research evidence.

More importantly, we propose a comprehensive and consistent approach to the issue of (non-) dissemination of research findings that, in part, focuses on the various key groups involved in the knowledge generation and dissemination process. The proposed approach includes three parts: (1) issues that need to be considered when exploring possible biases due to selective dissemination of research findings (What?), (2) stakeholders who could assume responsibility for the various stages of conducting a clinical trial and disseminating clinical trial documents (Who?) and (3) motivations that may lead the various players to disseminate findings selectively, thereby introducing bias in the dissemination process (Why?).

Issues that need to be considered when exploring possible biases due to selective dissemination of research findings (What?)

Based on our scoping review and our experience, the existing definitions of ‘publication bias’ remain rather vague, as there is currently no agreement in the scientific community about what should be considered a ‘publication’ and how it should be defined. It is unclear if only a full article in a peer-reviewed journal should be considered a publication, or whether other formats of publication, such as presentations at scientific conferences, governmental/institutional reports, book chapters, dissertations and theses, should also be considered as such. We decided to summarise the various ways of making research results available to the public by the term ‘dissemination’. The characteristics that need to be considered when disseminating research findings are presented in table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics that need to be considered when disseminating research findings (What?)

| Type of data | Format/product | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

*All raw data.

†Selection of outcome data.

‡Analysed outcome data.

§Including paywall restrictions.

Stakeholders who should assume responsibility for the various stages of conducting a clinical trial and disseminating clinical trial documents (Who?), and their motivations (Why?)

Within the OPEN Project, we have identified key groups who are part of the knowledge generation and dissemination process.12 When exploring their policies and procedures to deal with publication and associated forms of bias, it was striking that none of them assumed responsibility for, or indicated themselves to be in a position to tackle, this problem. Instead, each group considered it was ‘somebody else's problem’.13 14 The whole dissemination process seems to involve so many different players on various levels, that it can sometimes be difficult to identify clearly who is responsible for the (non-)dissemination of research findings at each stage of the process. In table 2, we list stakeholders who should assume responsibility for the various stages of conducting a clinical trial and disseminating of clinical trial documents (Who?). In table 3, the motivations that may lead the various players to selectively disseminate findings, thereby introducing bias in the dissemination process (Why?), are presented.

Table 2.

Responsibility/influence that different players could assume in the various steps of conducting a clinical trial and in the dissemination of clinical trial documents (Who?)

| Players in the dissemination process |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steps in trial conduct and dissemination | Researchers authors | Journal editors | Peer reviewers of journal articles | Funding agencies | Pharmaceutical and medical device manufacturers | Research ethics committees | Research institutions | Regulatory agencies | Trial register | Decision making bodies* | Readers/patients/patient organisations/benefit assessment agencies/HTA bodies |

| Research idea/research question | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Writing the study protocol | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Registering the study in a trial register | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| Submitting the study protocol for a journal publication | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||

| Publishing the study protocol | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||

| Conducting the study/assessing outcome measures | x | x | |||||||||

| Analysing data | x | x | x | ||||||||

| Writing and submitting a journal article | x | x | |||||||||

| Peer review | x | x | |||||||||

| Publishing journal research | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||

*Decision-making authorities in healthcare systems (eg, legal entities, such as the Federal Joint Committee in Germany).

Table 3.

Motivations of players that might lead to biased dissemination of research result (Why?)

| Players | Motivations |

|---|---|

| Researchers/authors | Publish or perish

|

| Journal editors | Frequent citations

|

| Peer reviewers | Tendency to confirm own expectations and hypotheses19

|

| (pharmaceutical and device) manufacturers | Marketing of their product

|

| Funding agencies | Increase in visibility

|

| Research ethics committees | Lack of financial and personal resources

|

| Research institutions | Increase in visibility

|

| Regulatory agencies | Lack of realising the public interest in unbiased research

|

| Decision making bodies* | Have an interest in transparency and try to add to the dissemination process through their submission and publishing procedures |

| Readers/patients/patient organisations | Readers and patients might be more interested in ‘positive’ or new research findings |

*Decision-making authorities in European healthcare systems, such as the Federal Joint Committee in Germany.

Discussion

The phenomenon of (non-)publication and/or non-dissemination of whole studies based on the nature and direction of the results has historically been referred to as ‘publication bias’.3 However, the scientific evidence-base can be distorted not only by the absence of a journal publication of a whole study, but results can also be reported only partially or in a delayed manner, or be misrepresented in a way that influences the take-up and interpretation of the findings. Thus, multiple problems, all related to the dissemination of study findings, can come into play.

In our scoping review we found that there is currently no consistent definition of ‘publication bias’ and a comprehensive framework for its description has not yet been developed. Multiple published definitions of ‘publication bias’ exist. Most of the articles (38/50) in our data set defined ‘publication bias’ as a form of selective publication due to various reasons. Thus, despite the serious consequences of this problem, we found in our scoping review that there is currently no consistent definition of ‘publication bias’ and a comprehensive framework for its description has not yet been developed.

As a first approach to a comprehensive and consistent framework of (non-) dissemination of research findings, we identified three characteristics ((1) ‘Type of data’, (2) ‘Format/Product’ and (3) ‘Accessibility’) that need to be considered when disseminating research findings (What?). We then focused on the various players who could assume responsibility for the various stages of conducting a clinical trial and disseminating of clinical trial documents (Who?). Furthermore, we tried to describe the motivations that might lead the various players to introduce bias in the dissemination process (Why?).

The proposed framework of (non-) dissemination of research findings is based on the results from literature search and expert consensus of the OPEN group. A limitation should be considered when interpreting our results. We conducted only a very limited literature search and included only 50 articles, since we were interested in the most prevalent definitions of ‘publication bias’ only. Since we only searched Web of Science, with the simple search term ‘publication bias’, our literature search might have favoured older publications and systematic reviews of primary research, and might have missed methodological publications. A more comprehensive literature search might have concluded in a wider range of definitions. Also, the representativeness of these articles might be limited since all of the included articles have been published in English, therefore language bias might also play a role.

The 2013 version of the Declaration of Helsinki states that ‘Researchers, authors, sponsors, editors and publishers all have ethical obligations with regard to the publication and dissemination of the results of research. Researchers have a duty to make publicly available the results of their research on human participants and are accountable for the completeness and accuracy of their reports’.26 Despite this, many research results never get disseminated. The (non-)dissemination of study results is of great importance because it distorts the evidence for clinical decision-making, which is increasingly based on syntheses of published research. Using the OPEN ‘What, Who and Why?’ framework, we were able to clearly structure and comprehensively describe the dissemination process and its responsible stakeholders. We believe that, together with the other results from the OPEN Project and the recommendations12 derived from these findings, our framework will facilitate the development of future policies and guidelines regarding the multifaceted issue of dissemination bias. We hope that it will help to decrease the problem of (non-)dissemination of research results and enable clinicians to base their medical decisions on the most comprehensive evidence available, which should ultimately increase the quality of patient care.

Acknowledgments

Members of ‘the OPEN consortium’ are listed below, and the authors acknowledge the discussions that helped to develop the new framework: Vittorio Bertelè: IRCCS—Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Milan, Italy; Xavier Bonfill: The Clinical Epidemiology & Public Health Department at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Spain; Marie-Charlotte Bouesseau: WHO, Geneva, Switzerland; Isabelle Boutron: INSERM U738 research unit, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France; Silvano Gallus: Department of Epidemiology, IRCCS—Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Milan, Italy; Silvio Garattini: IRCCS—Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Milan, Italy; Davina Ghersi: University of Sydney, Australia; Ghassan Karam: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; Michael Kulig: Federal Joint Committee, Berlin, Germany; Carlo La Vecchia: Department of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, University of Milan, Milan Italy; Jasper Littmann: CELLS (Centre for Ethics and Law in Life Sciences), Hannover Medical Scholl, Hannover, Germany; Mario Malički: University of Split School of Medicine, Split, Croatia; Bojana Murisic: Department of Epidemiology, IRCCS—Istituto di Ricerche Farmacologiche ‘Mario Negri’, Milan, Italy; Alexandra Nolting: Federal Joint Committee, Berlin, Germany; Hector Pardo: The Clinical Epidemiology & Public Health Department at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Spain; Matthias Perleth: Federal Joint Committee, Berlin, Germany; Philippe Ravaud: INSERM U738 research unit, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France; Andreas Reis: World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland; Lisa Schell: German Cochrane Centre, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; Christine Schmucker: German Cochrane Centre, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; Guido Schwarzer: Institute for Medical Biometry and Statistics, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany; Daniel Strech: CELLS (Centre for Ethics and Law in Life Sciences), Hannover Medical Scholl, Hannover, Germany; Ludovic Trinquart: INSERM U738 research unit, Paris Descartes University, Paris, France; Gerard Urrútia: The Clinical Epidemiology & Public Health Department at the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Spain; Robert Wolff: Kleijnen Systematic Reviews Ltd, York, UK.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Elizabeth Wager at @SideviewLiz and Joerg Meerpohl at @meerpohl

Contributors: DB and JJM conceived the study. DB, KFM, MB, JK, AM, EW, GA, EvE, DGA and JJM developed the new approach to the issue of (non-) dissemination of research findings. All the authors played a crucial role in the consensus process and in the interpretation of the data. KFM and DB drafted the manuscript with the help of JJM. KFM, MB, JK, AM, EW, GA, EvE, DGA, JJM and DB critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content. All the authors read and approved the final version before submission. KFM, JJM and DB are the guarantors. All the authors had full access to all of the data in the study and can take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: The OPEN Project (http://www.open-project.eu) is funded by the European Union Seventh Framework Programme (FP7—HEALTH.2011.4.1-2) under grant agreement n° 285453. Information about the grant can be found here: http://cordis.europa.eu/projects/rcn/100957_en.html. All researchers were independent from funders.

Competing interests: All the authors have completed the Unified Competing Interest form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare; AM, JK, JJM and EW received grants from the EU FP7 programme; EW declares personal fees from various pharmaceutical companies and publishers, personal fees from academic institutions (universities, hospitals), outside the submitted work, and the unpaid membership of the Advisory Board of the International Randomized Controlled Trial Numbering (ISRCTN) scheme; no other relationships or activities exist that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Higgins Julian PT, Green S. Cochrane handbook of systematic reviews of interventions. Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. JAMA 1990;263:1385–9. 10.1001/jama.1990.03440100097014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R et al. . Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337:867–72. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan AW, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT et al. . Empirical evidence for selective reporting of outcomes in randomized trials: comparison of protocols to published articles. JAMA 2004;291:2457–65. 10.1001/jama.291.20.2457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopewell S, Clarke M, Stewart L et al. . Time to publication for results of clinical trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):MR000011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pittler MH, Abbot NC, Harkness EF et al. . Location bias in controlled clinical trials of complementary/alternative therapies. J Clin Epidemiol 2000;53:485–9. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00220-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vickers A, Goyal N, Harland R et al. . Do certain countries produce only positive results? A systematic review of controlled trials. Controlled Clin Trials 1998;19:159–66. 10.1016/S0197-2456(97)00150-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Müller KF, Briel M, D'Amario A et al. . Defining publication bias: protocol for a systematic review of highly cited articles and proposal for a new framework. Syst Rev 2013;2:34 10.1186/2046-4053-2-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulkarni AV, Aziz B, Shams I et al. . Comparisons of citations in Web of Science, Scopus, and Google Scholar for articles published in general medical journals. JAMA 2009;302:1092–6. 10.1001/jama.2009.1307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song F, Parekh S, Hooper L et al. . Dissemination and publication of research findings: an updated review of related biases. Health Technol Assess 2010;14:iii, ix–xi, 1–193 10.3310/hta14080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bax L, Moons KG. Beyond publication bias. J Clin Epidemiol 2011;64:459–62. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meerpohl JJ, Schell LK, Bassler D et al. . Evidence-informed recommendations to reduce dissemination bias in clinical research: conclusions from the OPEN (Overcome failure to Publish nEgative fiNdings) project based on an international consensus meeting. BMJ Open 2015;5:e006666 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malički M, Marušić A, Consortium O. Is there a solution to publication bias? Researchers call for changes in dissemination of clinical research results. J Clin Epidemiol 2014;67:1103–10. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wager E, Williams P. Project Overcome failure to Publish nEgative fiNdings C. “Hardly worth the effort"? Medical journals’ policies and their editors’ and publishers’ views on trial registration and publication bias: quantitative and qualitative study. BMJ 2013;347:f5248 10.1136/bmj.f5248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fanelli D. Do Pressures to Publish Increase Scientist's Bias? An Empirical Support from US States Data. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10271 10.1371/journal.pone.0010271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stephan PE. The economics of science. J Econ Lit 1996;34:1199–235. [Google Scholar]

- 17.McDaniel MA, Rothstein HR, Whetzel DL. Publication bias: a case study of four test vendors. Pers Psychol 2006;59:927–53. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2006.00059.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Caelleigh AS. Impartial judgment by the “gatekeepers” of science: fallibility and accountability in the peer review process. Adv Health Sci Educ 2003;8:75–96. 10.1023/A:1022670432373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fanelli D. “Positive” results increase down the hierarchy of the sciences. PLoS ONE 2010;5:e10068 10.1371/journal.pone.0010068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lundh A, Barbateskovic M, Hróbjartsson A et al. . Conflicts of interest at medical journals: the influence of industry-supported randomised trials on journal impact factors and revenue—cohort study. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000354 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Olson CM, Rennie D, Cook D et al. . Publication bias in editorial decision making. JAMA 2002;287:2825–8. 10.1001/jama.287.21.2825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lexchin J, Bero LA, Djulbegovic B et al. . Pharmaceutical industry sponsorship and research outcome and quality: systematic review. BMJ 2003;326:1167–70. 10.1136/bmj.326.7400.1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sismondo S. Pharmaceutical company funding and its consequences: a qualitative systematic review. Contemp Clin Trials 2008;29:109–13. 10.1016/j.cct.2007.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J et al. . Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033 10.1002/14651858.MR000033.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strech D, Littmann J. Lack of proportionality. Seven specifications of public interest that override post-approval commercial interests on limited access to clinical data. Trials 2012;13:100 10.1186/1745-6215-13-100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]