Abstract

Objectives

We determined whether crowding at emergency shelters is associated with a higher incidence of sleep disturbance among disaster evacuees and identified the minimum required personal space at shelters.

Design

Retrospective review of medical charts.

Setting

30 shelter-based medical clinics in Ishinomaki, Japan, during the 46 days following the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011.

Participants

Shelter residents who visited eligible clinics.

Outcome measures

Based on the result of a locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing technique assessing the relationship between the mean space per evacuee and cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance at the shelter, eligible shelters were classified into crowded and non-crowded shelters. The cumulative incidence per 1000 evacuees was compared between groups, using a Mann-Whitney U test. To assess the association between shelter crowding and the daily incidence of sleep disturbance per 1000 evacuees, quasi–least squares method adjusting for potential confounders was used.

Results

The 30 shelters were categorised as crowded (mean space per evacuee <5.0 m2, 9 shelters) or non-crowded (≥5.0 m2, 21 shelters). The study included 9031 patients. Among the eligible patients, 1079 patients (11.9%) were diagnosed with sleep disturbance. Mean space per evacuee during the study period was 3.3 m2 (SD, 0.8 m2) at crowded shelters and 8.6 m2 (SD, 4.3 m2) at non-crowded shelters. The median cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance did not differ between the crowded shelters (2.3/1000 person-days (IQR, 1.6–5.4)) and non-crowded shelters (1.9/1000 person-days (IQR, 1.0–2.8); p=0.20). In contrast, after adjusting for potential confounders, crowded shelters had an increased daily incidence of sleep disturbance (2.6 per 1000 person-days; 95% CI 0.2 to 5.0/1000 person-days, p=0.03) compared to that at non-crowded shelters.

Conclusions

Crowding at shelters may exacerbate sleep disruptions in disaster evacuees; therefore, appropriate evacuation space requirements should be considered.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, SLEEP MEDICINE, MENTAL HEALTH, ACCIDENT & EMERGENCY MEDICINE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study is a large shelter-based study including 9031 evacuees at 30 shelters in disaster-affected areas.

This may be the first study to investigate the association between crowding at emergency shelters and the incidence of sleep disturbance during the acute postdisaster phase.

Crowding at emergency shelters was assessed here because it is an important issue that can be avoided by planning appropriate evacuation strategies.

Sleep disturbance was determined based on the diagnosis performed by the physicians in charge, which therefore may provide only a rough estimate of actual cases.

Background

In the acute phase following catastrophic disasters, sleep disturbance is a common stress reaction. Indeed, the literature has reported a prevalence ranging from 44% to 98% among disaster survivors who visited a psychiatric service.1–5 Although sleep disturbance is one of the warning signs among patients with posttraumatic stress disorders, sleep disturbance itself immediately after a traumatic event contributes to the development and persistence of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, and is deemed to be a risk factor for suicidal behaviour.6–9

In 2009, 335 natural disasters affected approximately 200 million survivors and accounted for more than $40 billion in economic damage globally.10 These catastrophic events impose multifactorial elements of stress on the affected people—for example, exposure to death, loss of family and property, and poor living conditions.11 12 While these traumatic experiences and change in socioeconomic status are deemed uncontrollable risk factors for sleep disturbance among disaster victims, crowding at emergency shelters, an indicator of poor living conditions, is considered as preventable with predisaster evacuation planning.13–15 One previous investigation suggested that crowding at emergency shelters was associated with sleep disturbance in the population.16 However, in this study, crowding at the emergency shelter was defined by the victim's personal judgment rather than by a specific, repeatable measure. Therefore, little is known about the relationship between crowding at the shelter and sleep disturbance during the acute postdisaster phase.

To address this knowledge gap, we conducted a retrospective study to test the hypothesis that limited personal space in emergency shelters is associated with sleep disturbance among evacuees, and to identify the minimum required personal space at the shelter to prevent or reduce sleep disturbances among evacuees during the acute postdisaster phase.

Methods

Design and setting

We conducted a retrospective study reviewing the medical charts recorded at the emergency shelter clinics in Ishinomaki city from 15 March through 30 April 2011. On 11 March 2011, the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake and Tsunami struck the northeastern coastal area of Japan. The disaster resulted in 15 000 deaths and forced 470 000 disaster-affected victims to stay in emergency shelters.17 Ishinomaki city is located in the northeast coastal area of Japan and was most severely affected by the disaster. The disaster destroyed 12 000 homes, killed 3500 people (2.1% of the total population) and resulted in 450 missing persons in this city.18 Immediately after the disaster, victims in this area evacuated to neighbouring shelters such as schools, community centres and libraries. Within days after the disaster, the medical teams of the Ishinomaki Area Medical Association (IAMA), which included several mental health care teams with psychiatrists, selected large shelters, mostly located at public facilities, and started providing medical care to the evacuees at the temporary medical clinics in these shelters.19

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Shelter

We included all emergency shelters in Ishinomaki city that had been public facilities before the disaster, and that had doubled as shelter clinics, and used them to conduct a nutrition survey. We excluded shelters if any of the following data were not available: the number of evacuees, amount of living space for evacuation, flood incursion, or day of the restoration of water supply.

Participants

We included evacuees who lived in any of the eligible shelters and presented to their shelter clinic during the study period. We excluded patients who lived outside of the shelters or whose medical records did not contain their identifiers or date of visit. Therefore, we counted patients only once if they visited at multiple shelter clinics, including clinics within their resident shelters. The Institutional Review Board of Fukui University approved the study with waiver of informed consent because this study does not include any invasive methods, interventions or human participants.20 21 Our study protocol was disclosed by Fukui University to provide an opportunity to refuse inclusion in this study.

Methods of measurements

Research assistants, who were blinded to the study, hypothesis-extracted the patient data from the medical records at the eligible clinics by using a standardised data collection form. These research assistants received a 1 h lecture from the principal investigator before the extraction. Abstractors collected patient-level data, including patient demographics, physician diagnosis, symptoms and disposition. We also collected the shelter-level data that were considered as risk factors for sleep disturbance among disaster evacuees—that is, the space per evacuee, nutrition status, area mortality, flood incursion and restoration of the water supply.13 22 23 The space per evacuee was defined as the daily amount of living space at the emergency shelter divided by the daily number of evacuees in the shelter. The nutrition status was determined by the survey of evacuees that was performed by Ishinomaki city daily over three continuous days in early April 2011. The nutrition status was calculated as the average delivered food calories per day, and was classified into quartiles: very low (≤1099 calories/day), low (1099–1568 calories/day), intermediate (1569–1718 calories/day) and high (>1718 calories/day). The area mortality was defined as the number of deaths directly resulting from the earthquake and tsunami divided by the total population before the disaster.24 The area mortality was also classified into quartiles: very low (<0.29%), low (0.29–0.40%), intermediate (0.41–0.97%) and high (>0.97%). Any shelter experiencing flood incursion after the tsunami was defined as a flooded shelter. Restoration of water supply was defined as the status that the water supply system was restored at the shelter. It did not include a temporary water supply provided by a tank truck. The daily number of evacuees and the daily nutrition status were provided by the Ishinomaki city office. Information on the amount of living space, flood incursion and day of water supply restoration were derived from the records of the shelter.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest were the cumulative incidence and the daily incidence of sleep disturbance per 1000 evacuees at each shelter during the study period. Sleep disturbance was defined as the diagnosis performed by a physician in charge. Previously established diagnostic criteria for sleep disturbance were not available during the disaster relief activities. Some medical records did not contain specific diagnoses but included prescriptions for the patient. In these cases, we diagnosed sleep disturbance if their prescriptions contained benzodiazepines, imidazopyridines or cyclopyrrolones as oral hypnotic medications. The cumulative incidence was calculated as the sum of the number of patients with sleep disturbance during the study period at each shelter divided by the sum of the daily number of evacuees at the shelter during the same period. Similarly, the daily incidence was calculated as the number of patients with sleep disturbance at each shelter divided by the number of evacuees on the same day. The daily incidence of sleep disturbance at each shelter was collected over the study period, thus it was considered as panel data.25

Statistical analysis

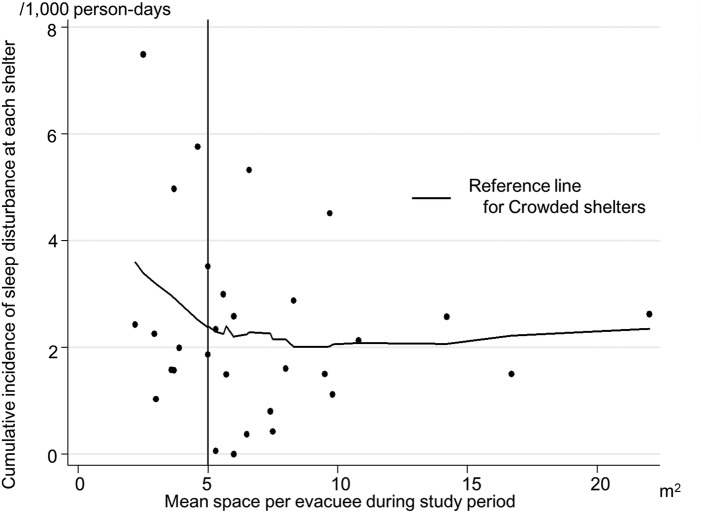

To classify the emergency shelters into two groups (crowded and non-crowded shelters), we evaluated the relationship between the mean space per evacuee at each shelter and cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance during the study period by using a locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing (LOESS) technique. This regression enables fitting of a smooth curve to a scatter diagram and can be applied to data that have non-linear relationships.26 Based on the result of the LOESS curve, we selected an inflection point as a cut-off value to define crowded and non-crowded shelters.

Next, we compared the cumulative and daily incidence of sleep disturbance between the crowded and non-crowded shelters using Mann-Whitney U tests. Then, to evaluate the adjusted association of crowding at the shelter with daily incidence of sleep disturbance, we conducted a panel data analysis using a quasi–least squares (QLS) method with a Gaussian distribution and Markov working correlation structures, along with the Huber-White heteroscedasticity-robust sandwich variance estimator. The panel data analysis provides more accurate inference than cross-sectional or time-series data analyses as panel data have more degrees of freedom and more sample variability.27 QLS is an alternative method for estimating correlation parameters within the framework of a generalised estimating equation (GEE), which is designed to deal with panel data.28 29 It allows for the implementation of Markov working correlation structures to account for the autocorrelation of the units with unequal time intervals and has not yet been implemented in the framework of a GEE.28 We constructed this model to investigate the range of change in daily incidence of sleep disturbance at the crowded shelters compared to that of the non-crowded shelters after adjusting for potential confounders—the nutrition status, area mortality, flooded shelter and restoration of water supply. We considered a p value of less than 0.05 as statistically significant. All analyses were performed using STATA V.12.1 (STATA Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

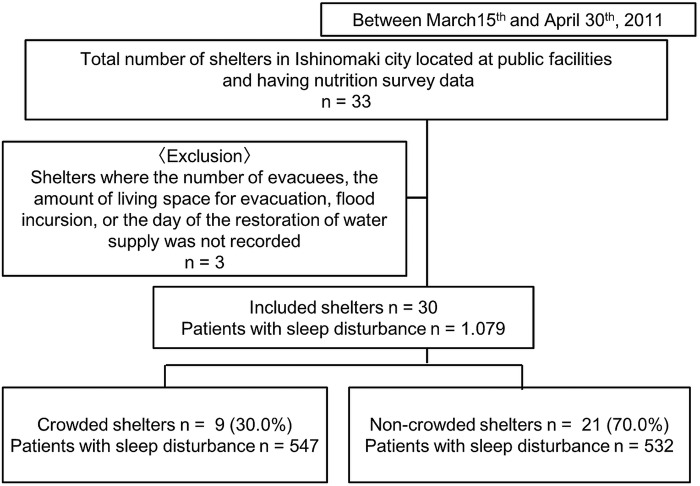

During the study period, there were 33 shelters located in the public facilities that also had nutrition survey data in Ishinomaki city. We excluded three shelters, as they had no information on the number of evacuees, amount of living space for evacuation, flood incursion or day of the restoration of water supply. Therefore, 30 shelter clinics were included in this study (figure 1). During this period, 11 532 patients presented to one of the shelter clinics. Of these, we excluded 1805 patients who lived outside of the shelters and 694 patients without a patient identifier or date of visit. The remaining 9031 patients (78.3%) were included in the study. Among the eligible patients, 1079 patients (11.9%) were diagnosed with sleep disturbance (table 1). The median cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance at total shelters was 2.1/1000 person-days (IQR, 1.4–2.9/1000 person-days). The median number of days when shelter clinics were available at total shelters was 22.5 days (IQR, 17.0–41.3). The daily incidence of sleep disturbance at total shelters was 1.9/1000 person-days (IQR, 0–5.9/1000 person-days).

Figure 1.

Shelter and patient recruitment diagram.

Table 1.

Patient and shelter characteristics

| Overall | Crowded shelters | Non-crowded shelters | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Total patients with sleep disturbance, n | 1079 | 547 | 532 | |

| Median patient age, years (IQR) | 65.0 (54.0–73.0) | 64.0 (54.0–73.0) | 65.0 (54.0–74.0) | 0.51 |

| Female, n (%) | 766 (71.0) | 394 (72.0) | 372 (70.0) | 0.32 |

| Shelter characteristics | ||||

| Number of shelters, n | 30 | 9 | 21 | |

| Median evacuee per day, n (IQR) | 7201 (5886–10 971) | 3198 (2805–4385) | 4003 (3081–6498) | <0.01 |

| Mean space per evacuee, m2 (SD) | 7.0 (4.4) | 3.3 (0.8) | 8.6 (4.3) | <0.01 |

| Median nutrition status, calories (IQR) | 1569 (1099–1719) | 1550 (1303–1719) | 1592 (1048–1713) | 0.70 |

| Number of flooded shelters, n (%) | 12 (40.0) | 4 (44.4) | 8 (38.1) | 0.32 |

| Median area mortality, % (IQR) | 0.4 (0.3–1.0) | 0.6 (0.3–2.7) | 0.4 (0.3–0.8) | 0.31 |

| Days postdisaster until the restoration of water supply (IQR) | 23.0 (9.0–33.0) | 24.5 (13.3–45.0) | 23.0 (9.0–34.0) | 0.38 |

| Total number of days shelter clinics were available | 785 | 291 | 494 | |

| Total number of days shelter clinics were available, day per shelter (IQR) | 22.5 (17.0–41.3) | 40.0 (19.0–45.5) | 21.0 (13.5–35.5) | 0.12 |

Crowded shelters: the mean space per evacuee at the shelters during study period <5.0 m2. Non-crowded shelters: the mean space per evacuee at the shelters during study period ≥5.0 m2.

A LOESS curve was used to determine the cut-off value for crowded and non-crowded shelters (figure 2). In accordance, 5.0 m2 was selected as the optimal cut-off value. Based on this cut-off, nine shelters were categorised as crowded (mean space per evacuee during the study period <5.0 m2) and 21 were categorised as non-crowded shelters (mean space per evacuee during the study period ≥5.0 m2).

Figure 2.

Relationship between mean space per evacuee during the study period at each shelter and the cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance at the shelter. This scatter diagram indicates the association between mean space per evacuee at each shelter and cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance at the shelter with a smooth-fit curve using the locally weighted scatter-plot smoothing technique.

Table 1 summarises the patient and shelter characteristics. The median age of the patients was 65.0 years (IQR, 54.0–73.0 years); the majority of patients (71.0%) were female. Mean space per evacuee during the study period was 3.3 m2 (SD, 0.8 m2) at the crowded shelters and 8.6 m2 (SD, 4.3 m2) at the non-crowded shelters. The median number of evacuees per day at the crowded shelters was smaller than that at the non-crowded shelters (median, 3198 (IQR 2805–4385) at the crowded shelters vs median, 4003 (IQR 3081–6498) at the non-crowded shelters; p<0.01). In contrast, there were no significant differences in the median nutrition status, the number of flooded shelters, median area mortality, or days postdisaster until the restoration of water supply between the crowded and non-crowded shelters (all p>0.05).

The median cumulative incidence of sleep disturbance did not differ between the crowded shelters (2.3/1000 person-days (IQR, 1.6–5.4)) and non-crowded shelters (1.9/1000 person-days (IQR, 1.0– 2.8); p=0.20). In contrast, the crowded shelters had a higher median daily incidence of sleep disturbance compared to the non-crowded shelters (2.4/1000 person-days (IQR, 0.0–6.9) at crowded shelters vs 0.0/1000 person-days (IQR, 0.0–5.5) at non-crowded shelters; p<0.01). Likewise, in the analysis adjusting for potential confounders (table 2), the crowded shelters had an increased daily incidence of sleep disturbance (adjusted difference, 2.6/1000 person-days (95% CI 0.2 to 5.0); p=0.03) when compared to non-crowded shelters.

Table 2.

Multivariable-adjusted differences in daily incidence of sleep disturbance per 1000 person-days in crowded and non-crowded shelters

| Variables | Difference in daily incidence of sleep disturbance per 1000 person-days | 95% CI | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shelter groups | |||

| Crowded shelters | Reference | ||

| Non-crowded shelters | 2.6 | 0.2 to 5.0 | 0.03 |

| Covariates | |||

| Nutrition status | |||

| Very low | Reference | ||

| Low | −2.6 | −4.8 to −0.3 | 0.03 |

| Intermediate | −1.5 | −3.9 to 0.9 | 0.23 |

| High | 1.1 | −0.8 to 3.0 | 0.27 |

| Flooded shelter | −0.5 | −2.5 to 1.4 | 0.58 |

| Area mortality | |||

| Very low | Reference | ||

| Low | −3.6 | −5.9 to −1.4 | <0.01 |

| Intermediate | −2.1 | −4.4 to 0.3 | 0.08 |

| High | −0.5 | −2.5 to 1.4 | 0.58 |

| Restoration of water supply | −2.0 | −4.3 to 0.2 | 0.07 |

Crowded shelters: the mean space per evacuee at the shelter during study period <5.0 m2; Non-crowded shelters: the mean space per evacuee at the shelter during study period ≥5.0 m2.

Discussion

In this chart review study of 9031 shelter evacuees after the Great Eastern Japan Earthquake and Tsunami, we found that crowding at shelters was associated with the daily incidence of sleep disturbance among evacuees. Specifically, as compared with non-crowded shelters, shelters with <5.0 m2 of space per evacuee during the acute phase of the disaster had an increased incidence of sleep disturbance. This novel finding would assist public health authorities in establishing appropriate evacuation plans and facilities to prevent the incidence of sleep disturbance among evacuees.15

Although shelter crowding had been considered a predictor of sleep disturbance in the postdisaster setting, little was known about the relationship.3 The lack of knowledge was likely attributable to the difficulty of conducting studies on the effects of a disaster; indeed, crowding at the shelter typically occurs during the acute phase of a disaster, when epidemiological study has little priority over the relief activity.30 Furthermore, experimental study to examine the impact of crowding in this setting is ethically inappropriate.30 To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate the association between crowding at shelter and sleep disturbance among evacuees.

Previous studies have reported that sleep disturbance among victims after a natural disaster was associated with socioeconomic factors, such as source of income, number of household members and loss of contact with people in the community.22 31 However, these factors are not modifiable when establishing evacuation plans. In contrast, in this study, our data demonstrated an association of crowding at the shelter with an increased incidence of sleep disturbance among evacuees. Crowding at the shelter is potentially a modifiable factor that can be avoided by appropriate evacuation planning. This finding supports the conventional wisdom about the association of shelter crowding with sleep disturbance by providing empirical evidence from a real disaster setting.

Our findings also support the current recommendations of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for the minimum required living space in emergency shelters. Emergency shelters located at public buildings are recommended to have 4.5–5.5 m2 per evacuee in cold climates because residents remain inside the shelters during daytime.15 Crowding at the shelter impairs the maintenance of privacy and emotional security of residents.15 Further, noise from neighbours can result in relationship difficulties.32 33 These stressors are deemed to contribute to sleep disturbance among the disaster-affected people.31 34 Thus, crowding at the shelter and its related consequences may impose significant levels of stress on evacuees with sleep disturbance expressed as the stress reaction.3 Our findings underscore the importance of a concordance with the UNHCR's recommendation for required living conditions at shelters, which would avoid further stressors on the victims at risk for developing disaster-related mental health issues. Otherwise, sleep disturbance and its subsequent effect on the development of other mental distress might result in significant burdens on the health care organisations at disaster-affected areas, which are typically already suffering from a shortage of medical resources.

In this study, the overwhelming majority of patients with sleep disturbance was older (>65 years). In addition, most of the patients were female. The reasons for older adults and female dominance in the prevalence of sleep disturbance are unclear and likely multifactorial. Although speculation should be avoided in this epidemiological data, previous investigations reported that the elderly and women are vulnerable to psychiatric conditions after a disaster, which might have led to a higher prevalence in these populations.4 32 33 This study suggested that older people and women might need specific strategies from mental health care organisations to mitigate their sleep problems and detect warning signs of psychiatric disorders after a catastrophic disaster.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, because our study was based on medical chart reviews for data collection, the incidence of sleep disturbance in the actual situations might be higher or lower than that in our study. However, assuming that misclassification occurred evenly in the crowded and non-crowded shelters, this non-differential misclassification would not have biased our inferences. Second, sleep disturbance was determined based on the diagnosis made by the physicians in charge or the prescription of oral hypnotic medications. Their diagnosis might have depended on patient self-assessment. Moreover, the hypnotic medications might have been used for purposes other than as sleep aids. Therefore, our study provides an estimate of sleep disorders exacerbated by the crowded emergency shelters without detecting underlying psychiatric disorders. 35 Third, as with any observational study, our findings might be confounded by unmeasured factors, such as socioeconomic status, the prevalence of pre-existing psychiatric disorders and the social network among disaster survivors.22 31 Fourth, we were unable to identify those who had moved from one shelter to another during the study period. However, movement between shelters was considered to be uncommon because the vast majority of evacuees moved to an unaffected area. Finally, our sample consisted of emergency shelters of an urban city in Japan. Therefore, our inferences may not be generalisable to other settings—for example, postdisaster periods in developing nations. Although formal validation of the study findings in different healthcare systems is necessary, the observed relationships are plausible and are likely present in different settings.

Conclusions

In this retrospective study of 9031 patients who presented to the temporary clinics located at emergency shelters during the acute phase after the Great Eastern Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011, we found that crowding at the shelter was associated with an increased daily incidence of sleep disturbance. Additionally, our finding suggests that 5.0 m2 per evacuee may serve as a minimum required living space per evacuee at emergency shelters; this finding is consistent with the UNHCR's recommendations. To reduce the occurrence of sleep disturbance among disaster evacuees, healthcare authorities and government agencies should establish evacuation plans in accordance with the UNHCR's recommendation.

Acknowledgments

All the authors appreciate the provision of data from the IAMA teams, Ishinomaki city officers and the administrator of each shelter.

Footnotes

Contributors: TK, KN and KH designed the study and contributed to writing the manuscript. TK performed statistical analysis. HM and OY contributed to data collection. KH and AH contributed to scientific review. TK and AT obtained funding. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the Daiwa Securities Health Foundation, a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientist (B) of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Number 2479134) and Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. The sponsors had no role in data collection, management, analysis, or interpretation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study was approved with waiver of informed consent for the chart review study by the Institutional Review Board of Fukui University.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rhoads J, Pearman T, Rick S. Clinical presentation and therapeutic interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder post-Katrina. Arch Psychiatr Nurs 2007;21:249–56. 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.North CS, Pfefferbaum B, Narayanan P et al. . Comparison of post-disaster psychiatric disorders after terrorist bombings in Nairobi and Oklahoma City. Br J Psychiatry 2005;186:487–93. 10.1192/bjp.186.6.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NSW Institute of Psychiatry Disaster Mental Health Handbook 2000. http://www.westga.edu/~vickir/ResourcesPublications/Professionals/Manuals,%20Guides,%20&%20Handbooks/Disaster%20MH%20Response.pdf (accessed 5 Jun 2014).

- 4.Mellman TA, David D, Kulick-Bell R et al. . Sleep disturbance and its relationship to psychiatric morbidity after Hurricane Andrew. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:1659–63. 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CC, Yeh TL, Yang YK et al. . Psychiatric morbidity and post-traumatic symptoms among survivors in the early stage following the 1999 earthquake in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res 2001;105:13–22. 10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00334-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Horne JA. Human sleep, sleep loss and behaviour. Implications for the prefrontal cortex and psychiatric disorder. Br J Psychiatry 1993;162:413–9. 10.1192/bjp.162.3.413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gerhart JI, Hall BJ, Russ EU et al. . Sleep disturbances predict later trauma-related distress: cross-panel investigation amidst violent turmoil. Health Psychol 2014;33:365–72. 10.1037/a0032572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ribeiro JD, Pease JL, Gutierrez PM et al. . Sleep problems outperform depression and hopelessness as cross-sectional and longitudinal predictors of suicidal ideation and behavior in young adults in the military. J Affect Disord 2012;136:743–50. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown TH, Mellman TA, Alfano CA et al. . Sleep fears, sleep disturbance, and PTSD symptoms in minority youth exposed to Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress 2011;24:575–80. 10.1002/jts.20680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Femke V, Jose R, Regina B. D. Guha-Sapir Annual Disaster Statistical Review 2009 2010. http://www.who.int/hac/techguidance/ems/annual_disaster_statistical_review_2009.pdf?ua=1 (accessed 19 Mar 2015).

- 11.Ursano RJ, Grieger TA, McCarroll JE. Prevention of posttraumatic stress: consultation, training, and early treatment. New York: Guilford Press, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kato H, Asukai N, Miyake Y et al. . Post-traumatic symptoms among younger and elderly evacuees in the early stages following the 1995 Hanshin-Awaji earthquake in Japan. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:477–81. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb10680.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mierswa T. Geriatric mental health disaster and emergency preparedness. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nara M, Ueda S, Aoki M et al. . The clinical utility of makeshift beds in disaster shelters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2013;7:573–7. 10.1017/dmp.2013.107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees Handbook for Emegencies Third edition 2007. http://www.unhcr.org/472af2972.html (accessed 3 Sep 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Varela E, Koustouki V, Davos CH et al. . Psychological consequences among adults following the 1999 earthquake in Athens, Greece. Disasters 2008;32:280–91. 10.1111/j.1467-7717.2008.01039.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism White Paper on Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan, 2010 2011. http://www.mlit.go.jp/english/white-paper/2010.pdf (accessed 2 Aug 2014).

- 18.City of Ishinomaki The situation of damage, 2011. http://www.city.ishinomaki.lg.jp/cont/10106000/7253/20141016145443.html (accessed 10 Jul 2014).

- 19.Japan Public Health Association The report of the disaster relief activities of the local governments in Japan to Great Japanese Eastern Earthquake and Tsunamis (Japanese). 2011. http://www.koshu-eisei.net/saigai/ssphforum.html (accessed 12 Nov 2015).

- 20.Halperin H, Paradis N, Mosesso V Jr et al. , American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee; American Heart Association Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative and Critical Care. Recommendations for implementation of community consultation and public disclosure under the Food and Drug Administration's “Exception from informed consent requirements for emergency research": a special report from the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and Council on Cardiopulmonary, Perioperative and Critical Care: endorsed by the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. Circulation 2007;116:1855–63. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.186661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nakayama T, Sakai M, Slingsby BT. Japan's ethical guidelines for epidemiologic research: a history of their development. J Epidemiol 2005;15:107–12. 10.2188/jea.15.107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Oyama M, Nakamura K, Suda Y et al. . Social network disruption as a major factor associated with psychological distress 3 years after the 2004 Niigata-Chuetsu earthquake in Japan. Environ Health Prev Med 2012;17:118–23. 10.1007/s12199-011-0225-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cairo JB, Dutta S, Nawaz H et al. . The prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder among adult earthquake survivors in Peru. Disaster Med Public Health Prep 2010;4:39–46. 10.1017/S1935789300002408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tani K. The distribution of the death and death rate classified by the Great Eastern Japanese Earthquake and tunamis affected regions (Japanese). The report of the Human Geography, Faculty of Education, Saitama University 2012(32):1–26.

- 25.Hsiao C. Panel data analysis—advantages and challenges. TEST 2007;16:1–22. 10.1007/s11749-007-0046-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleveland WS. Robust locally weighted regression and smoothing scatterplots. J Am Stat Assoc 1979;74:829–36. 10.1080/01621459.1979.10481038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsiao C, Mountain DC, Illman KH. A bayesian integration of end-use metering and conditional-demand analysis. J Bus Econ Stat 1995;13:315–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chaganty NR, Shults J. On eliminating the asymptotic bias in the quasi-least squares estimate of the correlation parameter. J Stat Plan Inference 1999;76:145–61. 10.1016/S0378-3758(98)00180-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woodward M. Epidemiology: study design and data analysis. CRC Press, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbs MS. Factors in the victim that mediate between disaster and psychopathology: a review. J Trauma Stress 1989;2:489–514. 10.1002/jts.2490020411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Matsumoto S, Yamaoka K, Inoue M et al. . Social ties may play a critical role in mitigating sleep difficulties in disaster-affected communities: a cross-sectional study in the Ishinomaki area, Japan. Sleep 2014;37:137–45. 10.5665/sleep.3324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.The American National Red Cross Disaster Mental Health Handbook | Disaster Services 2012. http://www.cdms.uci.edu/PDF/Disaster-Mental-Health-Handbook-Oct-2012.pdf (accessed 20 Jan 2015).

- 33.NSW Health and University of Western Sydney NSW Health Disaster Mental Health Manual 2012 2012. http://www.health.nsw.gov.au/emergency_preparedness/mental/Documents/NSW_Health_Disaster_MH_Manual_2012_Final_version_Feb_2013.pdf (accessed 28 Jul 2015).

- 34.Morse SA, MacMaster SA, Kodad V et al. . The impact of a sleep hygiene intervention on residents of a private residential facility for individuals with co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders: results of a pilot study. J Addict Nurs 2014;25:204–8. 10.1097/JAN.0000000000000050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.North CS, Pfefferbaum B. Mental health response to community disasters: a systematic review. JAMA 2013;310:507–18. 10.1001/jama.2013.107799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]