Abstract

Objectives

A large number of Canadians spend time in correctional facilities each year, and they are likely to have poor health compared to the general population. Relatively little health research has been conducted in Canada with a focus on people who experience detention or incarceration. We aimed to conduct a Delphi process with key stakeholders to define priorities for research in prison health in Canada for the next 10 years.

Setting

We conducted a Delphi process using an online survey with two rounds in 2014 and 2015.

Participants

We invited key stakeholders in prison health research in Canada to participate, which we defined as persons who had published research on prison health in Canada since 1994 and persons in the investigators’ professional networks. We invited 143 persons to participate in the first round and 59 participated. We invited 137 persons to participate in the second round and 67 participated.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

Participants suggested topics in the first round, and these topics were collated by investigators. We measured the level of agreement among participants that each collated topic was a priority for prison health research in Canada for the next 10 years, and defined priorities based on the level of agreement.

Results

In the first round, participants suggested 71 topics. In the second round, consensus was achieved that a large number of suggested topics were research priorities. Top priorities were diversion and alternatives to incarceration, social and community re-integration, creating healthy environments in prisons, healthcare in custody, continuity of healthcare, substance use disorders and the health of Aboriginal persons in custody.

Conclusions

Generated in an inclusive and systematic process, these findings should inform future research efforts to improve the health and healthcare of people who experience detention and incarceration in Canada.

Keywords: prisoners, Delphi technique, prisons, PUBLIC HEALTH, QUALITATIVE RESEARCH

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Participants represented diverse geographical areas, types of work and work settings relevant to prison health research in Canada.

Several investigators collated topics identified in the first round to capture breadth and specificity.

Some collated topics are broad and contain multiple components, which means that translating priorities into research plans will require further consideration and consultation.

Stopping the Delphi process after the second round precluded us from determining whether stability had been achieved regarding whether each topic was a priority and the relative priority of suggested topics, however, we decided to stop the process given the high level of consensus achieved for so many topics.

Introduction

Worldwide, more than 11 million people are incarcerated at any given time,1 and an estimated 30 million people move through the prison system annually.2 In Canada, there are approximately 251 629 adult admissions to provincial and territorial facilities and 8006 to federal facilities over a year,3 and an average of 40 000 people in correctional facilities on any given day.1 This translates into an estimated 1 in 250 people in Canada who are admitted to a correctional facility each year.

Substantial international evidence reveals that people who experience detention or incarceration have poor health compared with the general population, as indicated by the prevalence of mental illness, infectious disease, chronic disease, injury and mortality.4 In Canada, there is a paucity of research on the health of people who experience detention or incarceration.5 Research has the potential to identify ways to improve health in this population.6 In the context of much need and little research to date, efforts are needed to define priorities for research.7

We conducted a Delphi process with key stakeholders to define priorities for research in prison health in Canada for the next 10 years.

Methods

Participants

We invited persons to participate who had published research on prison health in Canada since 1994, as identified in a scoping review,5 or persons who were knowledgeable about and interested in prison health research who were in the professional networks of the study investigators. These persons included researchers, persons working in federal and provincial government agencies, persons working in non-governmental organisations and persons with a history of detention or incarceration in provincial or federal facilities in Canada.

Delphi process

The Delphi method is an iterative process in which a facilitator leads a group of experts to achieve consensus on a given topic,8–11 and involves conducting surveys anonymously with individuals to collect data, collating data, presenting results back to the group and having participants reassess their responses in light of group responses. The steps of collating and presenting data and the completion of surveys continue until consensus is achieved, and each of these steps is considered a ‘round.’

In December 2014, we emailed potential participants to provide information about the study, to invite them to participate in the first round, and to provide a link to an online survey. In the first round survey, we asked participants to specify the province and organisation in which they work and to list 5–10 research priorities for prison health research in Canada for the next 10 years. We specified that we were using the term prison health broadly to include persons in federal and provincial facilities, persons who are remanded (ie, detained in custody prior to sentencing) or sentenced, and also persons who have been released from custody.

Three investigators collated the first round responses through an iterative process in which we independently developed categories to group responses into broad topic areas, compared and came to consensus on categories and then grouped similar responses within categories into topics. In the second round in May 2015, we asked participants to provide information about the province and organisation in which they work, and to indicate whether they agreed that each collated topic was a priority by indicating one of five options on a Likert scale: strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree.9

We decided a priori to stop conducting rounds if participants reached consensus regarding whether each topic is a priority, or once we had conducted three rounds.8 9 We defined consensus a priori as more than 70% of participants indicating that they strongly agreed or agreed that the topic was a priority or that they disagreed or strongly disagreed that the topic was a priority, respectively.8

We obtained consent from participants, with completion of the online survey indicating consent, which was approved by the Research Ethics Board. The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) reviewed the study protocol and in May of 2015 approved one senior employee to participate as a representative of the organisation.

Results

For the first round, we invited 143 persons to participate: 106 persons who had published in this field and 37 persons in the investigators’ professional networks. Fifty-nine persons participated, and characteristics of their work are shown in table 1. Almost half of participants were from Ontario, more than half worked primarily as researchers and over 40% worked in a university setting. Most regions of Canada were represented and participants reported doing a variety of types of work and working in different settings. Participants suggested 410 topics, which we collated into 71 discrete priorities, shown in table 2.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants in rounds one and two of a Delphi process in 2015 to define priorities for prison health research in Canada in the next 10 years

| Round 1 (N=59), n (%) | Round 2 (N=67), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Geographical area where work is based | ||

| Ontario | 29 (49.2) | 33 (49.3) |

| British Columbia | 10 (16.9) | 14 (20.9) |

| Quebec | 5 (8.5) | 5 (7.5) |

| Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba* | 4 (6.8) | 6 (9.0) |

| Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island* | 3 (5.1) | 3 (4.5) |

| National/federal | 4 (6.8) | 4 (6.0) |

| Other | 4 (6.8) | 2 (3.0) |

| Type of work carried out most of the time | ||

| Research | 33 (55.9) | 39 (58.2) |

| Policy work | 7 (11.9) | 6 (9.0) |

| Clinical work | 5 (8.5) | 6 (9.0) |

| Health care management | 3 (5.1) | 2 (3.0) |

| Advocacy | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) |

| Other | 9 (15.3) | 10 (14.9) |

| Not specified | 0 (0) | 2 (3.0) |

| Setting in which most work carried out | ||

| University | 25 (42.4) | 36 (53.7) |

| Non-governmental organisation | 10 (16.9) | 9 (13.4) |

| Federal government | 8 (13.6) | 6 (9.0) |

| Provincial government | 3 (5.1) | 5 (7.5) |

| Correctional facility | 2 (3.4) | 2 (3.0) |

| Other | 11 (18.6) | 9 (13.4) |

*These provinces were grouped to prevent the identification of individual participants.

Table 2.

Collated topics suggested in first round of a Delphi process in 2015 as priorities for prison health research in Canada, N=59 participants

| Category | Topic |

|---|---|

| Prevention of detention/incarceration | Diversion and alternatives to incarceration, including for persons who use drugs and persons with mental illness, use of drug courts and addictions treatment, sentence length (mandatory minimum sentences) |

| Supporting youth at risk of criminal justice involvement, including youth with behavioural problems from trauma, early substance use, etc | |

| Reducing recidivism, including assessing risk factors for recidivism, and how health professionals can reduce risk | |

| Conditions in custody | Access to harm reduction tools and supports, including needle exchange |

| Staffing of correctional facilities, including staff training on mental health, healthcare staffing (24 h nursing) | |

| Health effects of overcrowding, including on communicable disease transmission | |

| Creating healthy environments in prisons, including trauma-informed environments, disability accommodation, programmes to enhance quality of life, personal safety and cultural safety, exercise and nutrition, effects of smoking ban | |

| Segregation: predictors of use, health effects of and alternatives to segregation | |

| Approach to offender rehabilitation: risk-needs-responsivity verses ‘good lives’ | |

| Treatment of prisoners/detainees by correctional staff, including use of force, restraints and OC/pepper spray | |

| Confidentiality | |

| value of accreditation of correctional facilities | |

| Healthcare in custody | Access to and quality of healthcare in custody, including mental healthcare, prenatal care, emergency care, preventive care, palliative care, dental care, geriatric medicine, pain management and contraception |

| Effective case management and individualised treatment programmes in custody | |

| Health education/health promotion, including for mental health | |

| Medications in custody: use, management (including forced withdrawal on admission), adherence (including off-label use), availability on formulary and alternatives to pharmacological therapies | |

| Challenges for healthcare providers in corrections: moral distress, perceptions and values | |

| Responsivity factors, that is, factors that impact on or enhance an offender’s ability to successfully undertake a programme, such as fetal alcohol spectrum disorder or brain injury | |

| Risk assessments and actuarial tools, including for women and Aboriginal persons | |

| Reintegration and continuity of care | Release/discharge planning, including the effect of planning on recidivism, dealing with pre-release anxiety |

| Continuity of healthcare at the time of admission to and release from custody, including communication of health information and medication adherence and including for persons with mental illness | |

| Social and community reintegration, including for persons with mental illness | |

| Developing partnerships between correctional facilities and community organisations | |

| Access to healthcare and other services after release from custody, including primary care | |

| Health and health service outcomes after release | |

| General health status | Health trajectories of people in custody, including biological vs chronological age, health effects of incarceration |

| Association between health and outcomes, including behaviour in custody, rehabilitation and recidivism | |

| Mortality: rates, causes and prevention, including use of data linkage studies | |

| Obesity | |

| Social determinants of health | Access to employment and education opportunities, including training |

| Housing after release | |

| Early childhood: relevance to criminal history and treatment, association between investment in early child development and parenting programmes and incarceration rates | |

| Building healthy relationships including with family and children, buildings skills in parenting, coping, anger management and conflict resolution | |

| Mental health | Mental disorders: screening, prevalence, comorbidities, etc including bipolar and unipolar depression, schizophrenia, post-traumatic stress disorder, gambling disorder and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |

| Mental health, continued | Interventions to address mental health issues, including risk management techniques, sex offender treatment, psychopathy treatment, Intermediate Mental Health Care and role of multidisciplinary teams |

| Substance use and abuse | Substance use disorders, including access to and outcomes of treatment in custody and after release, including in Aboriginal persons, women, parents and pregnant women |

| Non-abstinence-based substance abuse treatment approaches, including substitution therapies for opiates, such as methadone | |

| Overdose prevention training and naloxone distribution before release | |

| Drug interdiction strategies: effectiveness | |

| Prescription drug abuse | |

| Illegal drug use in correctional facilities, including injection drug use | |

| Chronic diseases | Chronic diseases: prevention, prevalence and management, including diabetes |

| Infectious diseases | Infection prevention and control in correctional facilities (including testing electric razors pre and postcleaning), including surveillance |

| HIV: Prevention, epidemiology and treatment, including treatment regimens, adherence and outcomes compared to community | |

| Hepatitis C: Epidemiology, prevention, natural history (does it suppress immune function?) and treatment | |

| Tuberculosis: Using DNA fingerprinting to identify clusters of tuberculosis cases in persons currently or previously in correctional facilities | |

| Predictors of recurrent MRSA infections | |

| Prevention and treatment of sexually transmitted infections | |

| Injury | Self-harm/self-injury: identification and management |

| Suicide prevention and epidemiology | |

| Injury prevention at the time of release | |

| Brain injury, including association with crime | |

| Subpopulations | Health of Aboriginal persons in custody, including mental health and Aboriginal treatment models |

| Abuse survivors, including survivors of residential schools | |

| Health issues for aging persons in custody, including compassionate release | |

| Women in custody, including supporting women’s voices and empowerment | |

| Gender and sexuality issues, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender health | |

| Support for incarcerated mothers and their newborn children, including mother-baby units | |

| Gangs | |

| Juveniles in custody and serving orders in the community | |

| Methodological approaches | Collaborations between legal and health research |

| Participatory research | |

| Economic analyses of health, social and offending outcomes after release from custody | |

| Interventions research and implementation, including animal-assisted interventions, peer-based interventions, psychologist vs correctional officer-administered interventions and community-based interventions | |

| Longitudinal studies of persons from the time in custody to long after release | |

| Multijurisdictional studies to compare outcomes across provinces/territories | |

| Policy research on professional and jurisdictional issues in the delivery of health services in custody | |

| Population-wide studies or representative samples, that is, research that is not limited to subgroups | |

| Theoretical medical research on health and justice | |

| Research ethics | Access to participate in research while in custody |

| Ability to give consent while in custody |

MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; OC, oleoresin capsicum.

For the second round, we invited 137 persons to participate: 99 persons who had published in this field (excluding six persons who declined participation and one for whom the contact information no longer worked) and 38 persons in the investigators’ professional networks (including the CSC representative). Sixty-seven persons participated. Their work characteristics are shown in table 1, and are similar to those of first round participants.

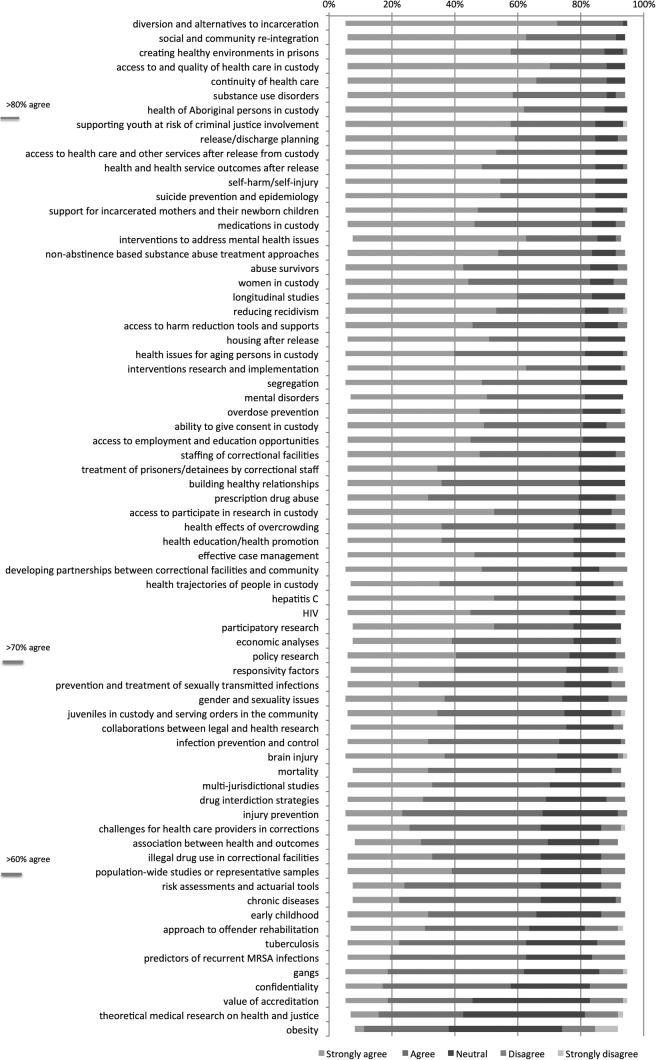

The distribution of responses is shown in figure 1. Using the a priori criterion for defining consensus, that is, 70% of participants indicating they strongly agreed or agreed that each topic was a priority, consensus was achieved for 45 of 71 topics. Using a less conservative definition of consensus, that is, 60%, consensus was achieved for 60 topics. Using a more conservative definition of consensus, that is, 80%, consensus was achieved for seven topics: diversion and alternatives to incarceration, social and community re-integration, creating healthy environments in prisons, access to and quality of healthcare in custody, continuity of healthcare at the time of admission to and release from custody, substance use disorders and the health of Aboriginal persons in custody.

Figure 1.

Per cent agreement by participants in a Delphi process in 2015 that each topic* is a priority for prison health research in Canada,† N=67 participants. MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. *Abbreviated titles for topics were used in this Figure. Full titles for each topic are provided in table 2; the full titles were used for the second round of the Delphi. †Sorted by the percent of participants who strongly agreed and agreed.

Based on the high level of consensus on most topics using the a priori criterion and the risk of a potentially low response rate in a third round (especially given the large number of suggested topics and the time it would take to consider each topic in light of other participants’ ratings), the investigators decided to not conduct another round.

Discussion

Through a consensus-building process, we have identified priority topics for research in prison health in Canada in the next 10 years. Most of the topics that were suggested by participants in the first round met our a priori criterion for consensus in the second round. The level of consensus was greater than 80% for seven topics, which were diversion from and alternatives to incarceration, healthcare and healthy environments in custody, community reintegration factors including social and community reintegration and continuity of healthcare, and more broadly, substance use disorders and the health of Aboriginal persons in custody.

The large number of topics identified as priorities is surprising, and may reflect the poor health of this population in Canada,12 the lack of research in prison health in Canada5 or a failure of dissemination and implementation of existing research from Canada and other jurisdictions.5 Any research on the priorities identified should proceed only after a comprehensive review of relevant research from Canada and other jurisdictions, and should build on existing promising or proven practices.7 That notwithstanding, many of the priorities identified in this study have been noted in other research that has looked broadly at the state of prison health research,4 6 providing external evidence that the results of this process are valid.

Strengths of this study include that there was a large number of participants with representation from diverse geographical areas, types of work and work settings; although a large majority of participants were primarily researchers and worked in university settings, this is likely appropriate for a study of stakeholders in prison health research and the high level of consensus for many topics indicates that persons across types of work and work settings agreed regarding their importance. We involved several investigators in collating topics from the first round to capture breadth and specificity while achieving a manageable number of topics to present in the second round.

Regarding potential limitations, the response rate was suboptimal, at 41.3% of those invited to participate in the first round and 48.9% of those invited to participate in the second round. We attempted to optimise participation by individually addressing each email and by sending reminders, and as noted, we achieved a sample that represented diverse groups. Some of the collated topics are broad and contain several components, for example ‘access to and quality of healthcare, including mental healthcare, prenatal care, emergency care, preventive care, palliative care, dental care, geriatric medicine, pain management, contraception;’ translating this priority and some other priorities into research plans will require further consideration and consultation. Stopping the Delphi process after the second round precluded us from determining whether stability had been achieved (ie, consistency of responses across rounds)11 regarding whether each topic was a priority and the relative priority of suggested topics, however, we decided to stop the process given the high level of consensus achieved for so many topics.

Derived through a systematic and inclusive methodology, the priorities identified in this study should inform the research agenda for prison health in Canada, and may also be relevant in other countries. Instead of relying on the perspective and knowledge of a single investigator or a small group of investigators, decisions about research should be determined based on the input of a diverse group of stakeholders, including patients and other affected populations.7 With this in mind, these priorities deserve attention by all stakeholders in prison health research in Canada.

The next steps to advancing research in this field should include creating a network of persons interested in prison health research, advocacy for research and for dedicated research funding and the development of programmes of research focused on some of the priorities identified in this study. Working on the most important research topics and ideally in collaboration, the prison health research community can take greater strides toward advancing the health and healthcare of this population.

Footnotes

Contributors: FGK led the study, developed the protocol and wrote the article. AS, KEM and LP contributed to analyses. All authors contributed to the study design and to revising the manuscript, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by a Planning Grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (grant number 316648). It was also supported by the Centre for Research on Inner City Health (CRICH), which is part of the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital. Fiona Kouyoumdjian receives salary support from a Fellowship from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research. The opinions, results and conclusions are those of the authors and are independent from the funding, supporting and participating agencies.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: St. Michael’s Hospital Research Ethics Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Walmsley R. World prison population list. 10th edn London: King's College London International Centre for Prison Studies, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kinner SA, Forsyth S, Williams G. Systematic review of record linkage studies of mortality in ex-prisoners: why (good) methods matter. Addiction 2013;108:38–49. 10.1111/add.12010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perrault S. Admissions to adult correctional services in Canada, 2011/2012. 2014. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/85-002-x/2014001/article/11918-eng.htm—a2 (accessed 14 Dec 2014).

- 4.Fazel S, Baillargeon J. The health of prisoners. Lancet 2011;377:956–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61053-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kouyoumdjian FG, Schuler A, Hwang SW et al. Research on the health of people who experience detention or incarceration in Canada: a scoping review. BMC public health 2015;15:419 10.1186/s12889-015-1758-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kouyoumdjian FG, McIsaac KE, Liauw J et al. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials of interventions to improve the health of persons during imprisonment and in the year after release. Am j Public Health 2015;105:e13–33. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014;383:156–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nur 2000;32:1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fink A, Kosecoff J, Chassin M et al. Consensus methods: characteristics and guidelines for use. Am J Public Health 1984;74:979–83. 10.2105/AJPH.74.9.979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. BMJ 1995;311:376–80. 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.von der Gracht H. Consensus measurement in Delphi studies: review and implications for future quality assurance. Technological Forecasting and Soc Change 2012;79 10.1016/j.techfore.2012.04.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouyoumdjian F, Schuler A, Hwang SW et al. The health status of prisoners in Canada: a narrative review. Canadian Family Physician. in press, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]